ABSTRACT

Aim: To critically evaluate single-case design (SCD) studies performed within the population of children/adolescents with cerebral palsy (CP).

Methods: A scoping review of SCD studies of children/adolescents with CP. Demographic, methodological, and statistical data were extracted. Articles were evaluated using the Risk of Bias in N-of-1 Trials (RoBiNT) Scale and the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) extension for N-of-1 trials (CENT 2015). Comments regarding strengths and limitations were analyzed.

Results: Studies investigated the effects of a wide range of interventions on various outcomes. Most SCD types were adopted in multiple studies. All studies used visual inspection rather than visual analysis, often complemented with basic statistical descriptives. Risk of bias was high, particularly concerning internal validity. Many CENT items were insufficiently reported. Several benefits and limitations of SCD were identified.

Conclusions: The quality of evidence from results of SCD studies needs to be increased through risk of bias reduction.

Introduction

Cerebral palsy (CP) is a life-long disorder that results from a lesion occurring in the developing brain and encompasses a large group of childhood movement and posture disorders. The rather stabile prevalence is 2–3.5 per 1000 live births over countries.Citation1 The disorder varies largely between individuals: in timing of the lesion, the clinical presentation, the site and severity of impairments, and activity and participation limitations. Consequently, rehabilitation of children and adolescents with CP requires an individualized approach.

Knowledge translation from research to clinical practice and vice versa is essential. This is a challenge in children with CP, since research has to deal with small and heterogeneous populations. In contrast, research within this population is dominated by group-based designs, and the randomized controlled trial (RCT) has for a long time been considered superior in intervention research.Citation2,Citation3 Because children may respond differently or even oppositely to the same intervention, application of group RCT designs leads to several problems in conducting and interpreting, such as very large confidence intervals for mean changes. In addition, RCTs generally include a narrow selection of the wide diversity in characteristics of children with CP and often end up with rather small study samples, limiting the generalizability of results to an even larger extent. Because the variability in treatment effects is masked, the applicability of RCT findings to clinical decision-making in individual children is very limited.Citation3 The single-case design (SCD) provides an alternative to the traditional group-based research to establish intervention effectiveness in this diverse and relatively small population.Citation4,Citation5

The SCD is a within-subject design, performed in one or a small number of cases. The participants serve as their own controls by comparing distinct experimental phases for the outcome of interest. This ordinarily includes a baseline phase to determine a representative stable state or trend, with which subsequent phases can be compared.Citation5,Citation6 The independent variable is deliberately manipulated by the researcher.Citation7–Citation9 The main outcomes are to be measured systematically and repeatedly within and across all phases, in order to assess individual change across different conditions.Citation3 There is a variety of designs adopting single-case methodology: the A-B design, the withdrawal/reversal (e.g., A-B-A) design, the multiple baseline design, the alternating treatments design, and the changing-criterion design. The design characteristics have been described in detail elsewhere.Citation3,Citation10 There is controversy over the types of single-case designs that are considered experimental. In the current study, the most prevalent view is adopted: the basic A-B design does not meet the prerequisites to establish a causal relationship between the independent and the dependent variable, and is therefore not a single-case experimental design (SCED). The other previously mentioned designs provide sufficient opportunity to demonstrate an experimental effect and are, therefore, regarded SCEDs.Citation10 Other perspectives on this matter should also be acknowledged. For instance, the What Works Clearinghouse SCD standards specifies that a design should allow for at least three demonstrations of an effect at different points in time in order to assess experimental control and, thus, considers the A-B-A design non-experimental.Citation11

The specific design used and the study’s methodology determine the confidence in any causal relationship found.Citation5 Visual inspection/analysis is a common methodology used for evaluating effectiveness of intervention effects within single-case designs,Citation11,Citation12 and can be complemented with statistical approaches.Citation5 Various means can be used to increase the study’s validity, such as multiple baselines, randomization, and replication within or between participants.Citation3,Citation5 A response-guided approach is also a commonly accepted option.Citation13 Some specific threats to internal validity make the SCD methodologically challenging. These include the issue of autocorrelation due to repeated measures within cases and the possibility of carry-over effects from interventions.Citation6,Citation10 In developing children return to baseline is not necessarily expected and favorable carry-over effects are desirable: retention of improvements after the treatment has ended is what is aimed for. Equally important, it would be unethical to withdraw an effective intervention in a subsequent phase, especially from a developing child. Likewise, lengthy baseline periods can be undesirable, and provoke resistance from families, who advocate the best care at all times.Citation3 These matters are to be carefully considered regarding SCD studies in children with CP.

SCD studies can provide a rigorous alternative to RCTs, respecting the heterogeneity regarding clinical performance and prognosis that characterize the population of children with CP.Citation3 Replication of results among cases increases generalization of findings, whereas dissimilar results enable identification of factors that interfere with the children’s response to the intervention. Hence, SCD studies inform treatment providers whether an intervention is expected to benefit their individual patient, facilitating translation of research findings into clinical practice.Citation3 Similarly, clinicians can employ a pragmatic SCD as a clinical decision tool to identify the best option for care for their patient.

The level of evidence from SCD studies is a subject of debate. Recently, there has been a shift towards acceptance of the SCD as a methodology equivalent to the RCT.Citation14 Some even consider the level of evidence from SCD studies to be the highest for clinical decision-making.Citation3,Citation14

Although SCD seems to be underusedCitation3, there has been no reviews of the use of SCDs within CP-related research, the methodological and statistical approaches applied, or the validity and the quality of reporting of these studies. A better understanding of the (dis)advantages of specific methodological aspects would contribute to epidemiological advancements in terms of design and analysis of SCD studies. This scoping review, therefore, aims to critically evaluate SCD studies performed within the population of children and adolescents with CP. Scoping reviews differ from systematic reviews because authors do not typically summarize and analyze the level of evidence of an intervention of interest within the included studies. Scoping studies also differ from narrative reviews in that the scoping process requires analytical reinterpretation of literature. Their aim could be to examine the extend, range, and nature of a certain research activity, like single-case methodology. That creates for us the possibility to incorporate the whole range of SCDs and to address questions beyond those related to intervention effectiveness.Citation15 The research questions that guided this scoping review were:

How many SCD studies have been performed in the population of children and adolescents with CP and what were their aims?

What methodological and statistical approaches were used in the available SCD studies?

What are the validity of these SCD studies and the quality of their reporting?

What are strengths and limitations of these SCD studies according to their authors?

Materials and Methods

The current study is explorative in nature, intending to systematically map the available literature relevant to the topic of interest. Because of the broadness and complexity of this aim, a scoping review was deemed most appropriate.

The methodological framework of Arksey and O’Malley,Citation16 and enhancements to this approach suggested by Levac et al.,Citation15 as well as the Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual 2015 (Methodology for JBI Scoping Reviews),Citation17 were adopted for designing this scoping review. Its objectives, inclusion criteria, and methods were specified in advance in a protocol.

Identification of Relevant Studies

Inclusion Criteria

Types of Participants

Studies with children and/or adolescents aged up to 21 years with CP were included. Studies of which >50% of the participants did not meet these criteria were excluded. At the outset of the study, the population of interest also consisted of children and adolescents with acquired brain injury. However, based on the more numerous results of the initial search than anticipated and to keep the study feasible, a protocol amendment was made to restrict the scoping review to CP only.

Concept

Given the scoping review design, it is appropriate to be as inclusive as possible in order to get a true overview of the application of SCDs in the research field. Although the A-B design does not comply with the criteria for SCED, it was expected that it is frequently used. Moreover, adopting methodological quality as an in-/exclusion criterion, thereby eliminating studies with low validity, is likely to positively bias the results in terms of the risk of bias assessment. Hence, studies reporting on any SCD were included.

SCD studies were defined as having the following characteristics, in accordance with the single-case designs technical documentation from What Works ClearinghouseCitation18:

“An individual ‘case’ is the unit of intervention and unit of data analysis. A case may be a single participant or a cluster of participants.”

“Within the design, the case provides its own control for purposes of comparison.”

“The outcome variable is measured repeatedly within and across different conditions or levels of the independent variable.”

An element of experimental manipulation by the researcher(s) was required to meet the definition of SCD.

Context

The focus was on pragmatic studies, carried out in clinical practice to determine the best option for care for the individual patient. Consequently, cross-sectional laboratory studies, in which different conditions were compared during the same measurement session, were not considered interventional and, therefore, excluded. No other limits were used for the setting, type of interventions, or outcomes.

Types of Sources

Completed or ongoing empirical research studies or protocols were included. Studies and dissertations published in English, Dutch, or German were considered for inclusion.

Search Strategy

The iterative process started with an initial limited search in the electronic databases EMBASE (Ovid interface) and MEDLINE (Ovid interface). The query included terms related to the types of participants (children with CP) and the concept (SCD) of interest. The text words of titles and abstracts along with the index words of retrieved reports were analyzed. Thereafter, the identified keywords and index words were used to perform a second amended search in the electronic databases CINAHL (EBSCO interface), EMBASE (Ovid interface), MEDLINE (Ovid interface) and PsycINFO (EBSCO interface), without restriction on the year of publication. The complete search query for all databases is presented in Appendix 1. The first author developed the search strategies, in consultation with a research librarian, and performed the searches.

In order to identify grey literature, the members of the European Academy of Childhood Disability (EACD) and the Australasian Academy for Cerebral Palsy and Developmental Medicine (AusACPDM) were requested by a newsletter to inform the project group of any published or unpublished SCD studies, executed either by their research group or associates.

Study Selection

The inclusion criteria were applied during two selection phases: (1) title and abstract screening, where in case of doubt the study remained included, and (2) assessing full texts for eligibility. The first and second author independently performed both phases of the selection process. One German article was evaluated by the first and last author instead. All cases of discrepancy were discussed until consensus was reached. An inter-rater agreement and reliability analysis using percentage of agreement and the Cohen’s kappa statistic, respectively, were performed to determine consistency between raters in assessing eligibility of the full-text publications. The online Covidence systematic review software (Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia) was used for management of the study.

Data Extraction

Study Characteristics, and Methodological and Statistical Approaches

Study characteristics as well as methodological and statistical approaches were extracted. Two independent reviewers (first and second author) carried out the data collection by using a customized digital charting form. Any differences were resolved via consensus. A third reviewer (last author) mediated if required.

Risk of Bias and Quality of Reporting

The selected articles were graded for risk of bias using the Risk of Bias in N-of-1 Trials (RoBiNT) Scale. The RoBiNT Scale has been developed to critically appraise SCD studies, primarily in the field of neurorehabilitation. It contains a 7-item Internal Validity subscale and an 8-item External Validity and Interpretation subscale. The scales cover items such as ‘blinding of people involved in the intervention’ and ‘generalization’. For each item, 0, 1, or 2 points can be awarded, which enables a total score from 0 to 30 to be calculated. The higher the score, the lower the risk of bias. Inter-rater reliability and construct validity of the RoBiNT Scale are satisfactory and an extensive manual is available, providing scoring procedures and rating guidelines.Citation10,Citation19

The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) extension for N-of-1 trials (CENT 2015) was used to evaluate the quality of reporting of the full-text publications. This standard provides guidance to facilitate preparation and appraisal of, specifically, multiple crossover N-of-1 trials.Citation20 This is in contrast to the RoBiNT Scale, which has a wider application. The CENT comprises the topics ‘title and abstract’, ‘introduction’, ‘methods’, ‘results’, ‘discussion’, and ‘other information’, and is reported in a checklist as well as an ‘explanation and elaboration’ document.Citation20 In this review, all 25 items and 44 sub-items of the CENT were rated as sufficiently reported, insufficiently reported, or not applicable.

To increase consistency between the reviewers, the first, second, and last author independently assessed five studies. They reflected on the results and aligned their conceptualizations of the appraisal tools. Thereafter, the first and second author appraised the risk of bias and reporting quality for all studies independently. Disagreements between the reviewers’ assessments were debated and a final decision agreed upon. To determine inter-rater agreement of the risk of bias appraisal, percentage of agreement between the assessors was calculated per item of the RoBiNT Scale, as well as for the Internal Validity Subscale, External Validity and Interpretation Subscale, and total score.

Content Analysis

The first author searched the introduction, methods, and discussion sections of all included studies for comments regarding the strengths and limitations of studies, including rationales for using SCD approaches. Relevant sentences or paragraphs were tracked and coded per study. These coded extracts were analyzed for recurrent issues across studies and overarching themes were sought.

Consultation

A consultation element was embedded in the scoping review to enhance the validity of the study results. The stakeholder consulted (PO) was a professor of educational and behavioral statistics and methodology, with expertise in SCD research. A report describing the preliminary findings was shared with PO to inform the consultation, followed by a discussion of his perspectives. The provided insights were incorporated into this paper.

Results

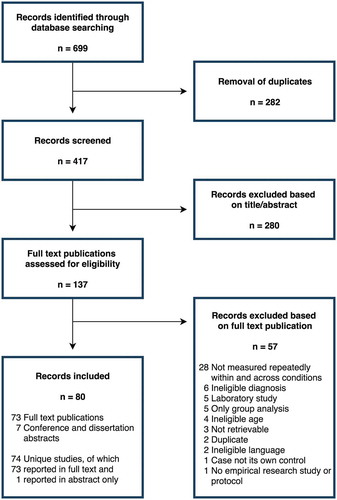

displays the scoping review flow diagram. After removal of duplicates, the database search (last updated 13 September 2018) retrieved 417 citations. The newsletter item, which was sent to 1261 EACD and AusACPDM members, obtained no responses. Eighty published records were included in the review: 73 full-text publications (including one dissertation) and seven conference and dissertation abstracts. The records reported on 74 unique studies. One of the full-text publications reported on two separate studies and another described methods only. The inter-rater agreement of full-text assessment was found to be 86.9%. Inter-rater reliability was substantial: Cohen’s kappa = 0.72 (p < .0.001).

Study Characteristics

Appendix 2 contains the aims and characteristics of the included studies. The studies focused on a wide range of interventions and outcomes. Interventions of interest in multiple studies were interactive video gaming or virtual reality (eight studies), orthotics (seven studies), seating and positioning (five studies), alternative and augmentative communication (four studies), neurodevelopmental therapy (three studies), Constrained Induced Movement Therapy (CIMT) (two studies), early intervention (two studies), electrical stimulation (two studies), and oral motor treatment (two studies). Besides establishing effects, a few studies aimed to answer feasibility questions, for instance concerning satisfaction of users with the treatment(s). The sample sizes varied from one to 14 children and adolescents. The demographics of participants were diverse with respect to types of CP, age, and gender.

Methodological and Statistical Approaches

As can be seen from , the withdrawal/reversal design was most frequently used (39.2%), followed by the A-B design (29.7%), the multiple baseline design (18.9%), and the alternating treatments design (9.5%). The changing-criterion design was seldom used (2.7%). The data analysis of all studies comprised visual inspection to a greater or lesser degree. Nevertheless, none of the studies systematically evaluated all six components (i.e., level, trend, variability, immediacy of the effect, overlap, and consistency of data patterns across similar phases) that are considered fundamental to demonstrate whether a causal relation exists and which would have been regarded as a visual analysis.Citation11,Citation12,Citation18 The descriptive two-standard deviation band method and the split-middle technique (celeration line) were the most frequently mentioned statistical approaches, used in 25.3% and 17.6% of the studies, respectively.

Table 1. Methodological and statistical approaches of studies.

Risk of Bias

presents the results obtained from the risk of bias appraisal. The included studies scored on average 11.2 points on the RoBiNT Scale. Total scores ranged from 4 to 22 points. The Interval Validity Subscale mean score was 3.6 points. The mean score on the External Validity and Interpretation Subscale was 7.6 points, more than twice as high.

Table 2. Risk of bias per item of the RoBiNT Scale, and inter-rater agreement of RoBiNT Scale scores (n = 73).

Internal Validity Subscale

For the item ‘design with control’, 37.0% of the articles scored 0 points, 39.7% scored 1 point and 23.3% scored 2 points. Many multiple baseline designs were rewarded 0 points since concurrency was not demonstrated. In as many as 86.3% of the studies, no randomization was applied. With regard to item 3, it was found that 41.1% and 47.9% of the studies used at least 3 or at least 5 data points or sets of alternating sequences, respectively. Blinding of either the participant or the practitioner involved in the intervention was not applied in 95.9% of the studies. The majority of studies (80.8%) also did not use a blinded assessor. As to inter-rater agreement, 0 points, 1 point, and 2 points were given to 64.4%, 20.5%, and 15.1% of the studies, respectively. Finally, it appeared that 91.8% of the studies did not (adequately) confirm treatment adherence.

External Validity and Interpretation Subscale

Although half of the studies did sufficiently report on relevant biomedical variables, none provided an analysis of the baseline conditions or behaviors using functional status, case formulation, or other systematic investigation. Only 23.3% of the studies described both the general location and the specific environment in which the intervention was conducted. A large proportion of the studies (82.2%) sufficiently defined the dependent variable (outcome), including the measuring method. Similarly, 61.6% of the studies described the content of the intervention and the procedure of delivery in detail. For the item ‘raw data record’ a score of 1 point was awarded to the largest group of studies. Many studies were penalized because the figures were of such poor quality that the data points could not be read. The data analysis of studies was rated 0 points in 46.6%, 1 point in 32.9%, and 2 points in 20.5% of the studies. Many studies did conduct statistical analyses, but justification was missing, which is a requirement for a maximum score of 2 points. A total of 34.2% of studies did not contain any replication. The study was replicated (across participants, settings, behaviors, or practitioners) once or twice in 27.4% of the studies, and three or more times in 38.4% of the studies. Just two studies indicated a generalization measure to determine transfer of intervention effects to other variables or settings.

Inter-rater Agreement

The inter-rater agreement between the two assessors per item of the RoBiNT Scale ranged from 53% to 99% (). The agreement for the Internal Validity Subscale, External Validity and Interpretation Subscale, and total score were 79%, 72%, and 75%, respectively.

Quality of Reporting

compares the proportion of studies that sufficiently and insufficiently reported the items of the CENT.

Table 3. Quality of reporting appraisal, per item of the CENT (n = 72).

Title and Abstract

Merely a quarter of the publications identified their study as a SCD in the title. According to the specific CENT guidance, the abstract should describe such items as the trial design, participant(s), interventions, objective, outcome, randomization, blinding, results, and conclusion. None of the included studies fully met these criteria. Particularly, randomization and blinding procedures, and harms were often missing.

Introduction

The majority of the studies reported the scientific background, explained the rationale, and specified the objectives or hypotheses. However, only 29.2% of the authors reported their rationale for using a SCD approach.

Methods

Although 59.7% of the studies sufficiently described the trial design, only 26.4% described whether and how methods changed after the start of the study. Patient characteristics or eligibility criteria were well reported. Still, in most studies information on settings and locations was lacking, and it was not addressed whether both a health research ethics board reviewed and approved the research study and parent and/or patient consent or assent was obtained. About half of the studies reported the interventions for each period insufficiently. Baseline intervention procedures were frequently not reported. While 76.4% of the studies completely defined pre-specified primary and secondary outcomes, the minority adequately described the measurement properties of outcome assessment tools and changes to outcomes after the trial commenced. None of the studies defined how sample size was determined nor explained interim analysis and stopping guidelines. Only four studies reported both whether and how randomization was applied. Consequently, item numbers 8b, 9, and 10 were often not applicable. Studies that did use randomization generally did not describe the type of randomization, allocation concealment mechanism, and implementation. Blinding was not mentioned in 81.9% of the studies. A total of 72.2% of the studies satisfactorily reported the statistical methods that were used to summarize data and compare interventions. On the other hand, methods of quantitative synthesis of individual trial data and assessing heterogeneity between participants (for series), and methods to account for carryover effect, period effects, and intra-subject correlation were reported in only 11.1% and 12.5% of the studies, respectively.

Results

Overall, the participant flow was well reported. Dates of the recruitment and follow-up period were not defined, with the exception of four studies. Further, just 13.9% of the studies reported whether and why any periods or the study itself were stopped early. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics were too limited or not provided at all in 61.1% of the studies. Most studies sufficiently reported the numbers analyzed. The assessment of outcomes and estimation revealed opposing results: 81.9% of studies presented results for each outcome and each period, while no more than three studies estimated an effect size and its precision. The items concerning binary outcomes and ancillary analysis were mainly irrelevant. Few studies (15.3%) reported any harms or unintended effects of interventions.

Discussion

Limitations, generalizability, and interpretation of the results were discussed satisfactorily in comparable proportions of studies: 55.6%, 58.3%, and 62.5%, respectively.

Other Information

A registration or protocol of the study was not referred to in any of the publications. Sources of funding were named in about half of the studies.

Development over Time

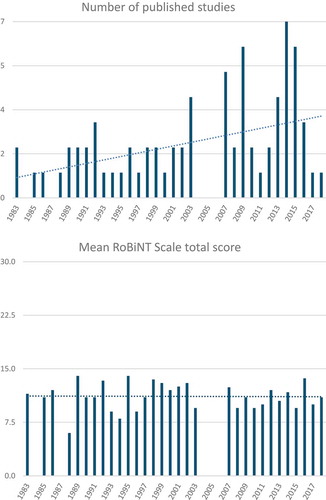

From 1983 to 2018, the number of published SCD studies fluctuated between 0 and 7 per year, with an increase over time (). The mean RoBiNT Scale total score of studies published each year remained stable over the last decades ().

Content Analysis

The analysis of the authors’ commentaries on the utilization of SCDs resulted in a synthesis of the findings in two themes: applicability of the SCD and methodological considerations.

Applicability of the SCD

The most mentioned argument for applying a SCD was the appropriateness of this design for the heterogeneous population of children with CP and related variability in responses to interventions. Authors specified that the SCD approach met the demands of individualized (evaluation of) treatments, thereby being highly relevant for clinical practice. A secondary reason for using a SCD was limited availability of potential participants. Finally, some expressed the SCD to be a rigorous design with a high level of internal validity.

Authors frequently discussed limited generalizability of their findings, either to patients comparable to the children under research or to a wider population, as a major limitation of their study. Likewise, a small sample size was mentioned as a limitation. Replication or a follow-up study in a larger and/or more heterogeneous sample and using a longer follow-up period were often recommended. Several studies explicitly planned or recommended an RCT following the SCD study. In agreement with this, many authors referred to their work as preliminary, exploratory, or a pilot study.

Methodological Considerations

Practical concerns and constrains limited the possibilities of the research design. These were often inherent to the clinical nature of the study. Additionally, in many cases illness, holidays, or other events interrupted or otherwise disturbed the study procedures. Another recurrent example was the lack of a blinded assessor, due to insufficient resources.

Concerning the study population, authors noticed that motivation, compliance, rapport with the assessor, and other mood and behavioral aspects of the child affected the assessment process. Second, confounding effects of growth, maturity and the ongoing process of motor development were recognized in the interpretation of findings. Researchers explained that they carefully considered the time and effort required of participants in order to ease the burden on children and their families, sometimes at the expense of study rigor.

The relevance as well as the challenge of standardized measurement conditions (e.g., same time each day) were acknowledged. Moreover, authors balanced the importance of outcome measures being sensitive to change with clinical relevance and ease of administration. A few specifically stated that the Gross Motor Function Measure (GMFM) was not responsive to changes in the case of short intervals between measurements.

In several publications, it was argued that withdrawal of treatment was inappropriate, either ethically or because permanent change of the child’s functioning was intended. In some other studies, where researchers did withdraw an intervention, a carry-over effect was demonstrated. Furthermore, some authors identified other limitations of their studies related to the SCD: the absence of a control group, too few data points collected, the variability of data points within phases and thus no stable baseline, and practice effects.

Discussion

With respect to the first research question of this study, 74 SCD studies have been identified. These studies aimed to investigate the effects of a range of interventions on a variety of outcomes. The second question focused on the methodological and statistical approaches of the included studies. Except for the changing-criterion design, all SCD types were adopted in multiple studies. All studies used visual inspection rather than visual analysis, often complemented with inconsistent, basic statistical approaches. The third question sought to determine the risk of bias and quality of reporting. The overall risk of bias was relatively high, particularly in terms of internal validity. Additionally, many items of the CENT were insufficiently reported in the included full-text publications. Although the annual number of studies increased, their risk of bias did not decrease over time. The fourth and last question was designed to identify the strengths and limitations of SCD studies. Benefits and limitations of the applicability of the SCD in the population of interest were determined and several methodological considerations discussed.

The A-B design and the non-concurrent multiple baseline design, which can be seen as a series of A-B designs,Citation10 were included in this scoping review because they encompass single-case methodology. It should be emphasized, though, that generally causal inferences cannot be derived from these designs.Citation10 A recent article argued that A-B designs in which the start point of the treatment phase is randomized can be valid experimental designs under certain conditions,Citation98 but the numerous studies included in this review that used this design did not comply with these criteria. The analysis of SCD is controversial in terms of the applicability of visual and (advanced) statistical analyses available. Beyond this debate, there is abundant room for improvement in the reporting of the analyses used, their rationales, and the techniques used. Due to the nature of the interventions in pediatric rehabilitation, in most studies, neither families nor professionals involved in delivery of the intervention could have been blinded. Except for corresponding Item 4 of the RoBiNT Scale, studies missed opportunities to comply with quality criteria for SCDs. Contrary to expectations, this review did not find an increase of the total score of the RoBiNT Scale over time. This may be explained by the fact that guidelines for SCD design and reporting were only published some 10 years ago.Citation18,Citation99 One of the findings of the content analysis was that SCD studies in the clinical setting are facing practical restrains and limited resources, which negatively affects the capability to perform the experiment in conformity with recommended procedures. This is a possible explanation for the high risk of bias of studies. Similarly, acceptable measurement burdens for participating families may have been prioritized over measurement intensity or phase lengths.

Next to the systematic and thorough search and data charting process, the consultation phase in which an expert in SCD statistics and methodology reviewed the results strengthened the validity of this scoping review. Unfortunately, the lack of response to the newsletter items did not allow for the inclusion of grey literature. It is possible, therefore, that unpublished studies were missed. The CENT reporting standard was chosen along with the RoBiNT Scale to cover both the policies of medical and behavioral sciences. Unlike the alternative Single-Case Reporting Guideline In BEhavioural Interventions (SCRIBE), the CENT has been specifically designed for the medical N-of-1 trial, i.e., a multiple crossover design. As a consequence, not all items were equally relevant for each type of SCD. Hence, results of the quality or reporting assessment need to be interpreted with caution to avoid overestimating the inadequacy of reporting. Last, the inter-rater agreement of the risk of bias appraisal was slightly lower than the agreement of 81% between trained novice raters in an inter-rater reliability study of the RoBiNT Scale.Citation10

We are convinced that adopting SCD methodology is the way forward for clinically meaningful intervention research in the heterogeneous population of children and adolescents with CP. Many authors of included studies confirmed this potential of the SCD. Gaps and recommendations for using this type of design are also discussed in a recent publication.Citation3 The authors state that single-case methodology could be very useful in pediatric rehabilitation, because it describes the variability of responses within and between individuals. The importance of the research question as leading for the choice of a design type within the field of single-case methodology is underlined, as multiple designs adopting single-case methodology are applicable to CP-research. A typical research question in this field should include a clear definition of the independent and dependent variable: are changes initiated by the independent variable associated with changes in the outcome to be measured? An outcome measure should be able to pick up change over time on an individual basis. However, that still is a point of debate, as responsiveness is not yet investigated for a lot of outcome measure in the field of CP, and the approach for responsiveness on an individual basis is not yet clear. More research on this point is needed. The paper of Romeiser-Logan et al. discusses some SCD examples in an extensive way.Citation3

Epidemiological principles and design standards are available to guide the planning of a SCD study and increase the credibility of results. General tools include the RoBiNT Scale, the SCRIBE, the CENT, and the SCD standards by What Works Clearinghouse.Citation10,Citation18–Citation20,Citation100 So far only one CP-specific guideline is available, which is rather concise, with limited testing for validity.Citation101 Hence, standards should be advanced for the complex rehabilitation setting to fit the specific needs of pediatric rehabilitation. To initiate a trend towards improvement of validity, it is imperative that researchers follow available recommendations for SCDs. In addition, the importance of generic principles of intervention research should not be underestimated, such as clinical relevance of treatments and reporting of harms.

A number of issues is still under debate among experts and requires consensus, for instance, consistent SCD terminology and appropriate statistical approaches per design. Statistics developed for this type of studies, next to the more traditional focus on the visual techniques for analysis, will open the possibility to combine studies in a meta-analysis approach. Best practices need to be agreed upon for CP-related research, supplementing earlier work.Citation3 Some specific concerns need particular attention. On the one hand, the non-reversal multiple baseline design seems most convenient, since many CP-treatments are intended to produce a permanent change. On the other hand, if no immediate effect is expected, it will reduce the suitability of the multiple baseline design. Hence, directions for the applicability of SCD designs to certain research situations are desired. Furthermore, the frequently repeated measures require instruments with specific psychometric properties that are at the same time clinically relevant and convenient to administer often. A core set of suitable measurement instruments could aid in the selection from the many options available in pediatric rehabilitation.

The SCD has potential in the context of personalized evidence-based medicine in children and adolescents with CP, provided that the level of evidence of results is increased by minimizing risk of bias. Therefore, it is imperative that researchers comply with recommendations and guidelines. This requires researchers and health-care givers in the field to thoroughly invest in gaining knowledge about the typical features of single-case methodology. We invite the field to fill the gaps identified by us by building the evidence base for a SCD methodology that is highly valid and relevant to clinical practice.

Declaration of interest statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- Colver A, Fairhurst C, Pharoah PO. Cerebral palsy. Lancet. 2014;383:1240–49. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61835-8

- Krasny-Pacini A, Evans J. Single-case experimental designs to assess intervention effectiveness in rehabilitation: A practical guide. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2018;61:164–79. doi:10.1016/j.rehab.2017.12.002

- Romeiser-Logan L, Slaughter R, Hickman R. Single-subject research designs in pediatric rehabilitation: a valuable step towards knowledge translation. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2017;59:574–80. doi:10.1111/dmcn.13405

- Evans JJ, Gast DL, Perdices M, Manolov R. Single case experimental designs: introduction to a special issue of neuropsychological rehabilitation. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2014;24:305–14. doi:10.1080/09602011.2014.903198

- Tate RL, Perdices M. Single-case experimental designs for clinical research and neurorehabilitation settings: planning, conduct, analysis and reporting. Abingdon (United Kingdom). New York (NY): Routledge; 2018.

- Smith JD. Single-case experimental designs: a systematic review of published research and current standards. Psychol Methods. 2012;17:510–50. doi:10.1037/a0029312

- Barlow DH, Nock MK, Hersen M. Single case experimental designs: strategies for studying behavior for change. Boston (MA): Pearson; 2009.

- Kazdin AE. Single-case research designs: methods for clinical and applied settings. New York (NY): Oxford University Press; 2011.

- Ledford JR, Gast DL. Single case research methodology: applications in special education and behavioral sciences. New York (NY): Routledge; 2018.

- Tate RL, Rosenkoetter U, Wakim D, Sigmundsdottir L, Doubledaty J, Togher L, Perdices, M. The risk of bias in N-of-1 trials (RoBiNT) scale: an expanded manual for the critical appraisal of single-case reports. Sydney (Australia); 2015.

- Kratochwill TR, Hitchcock JH, Horner RH, Levin JR, Odom SL, Rindskopf DM, Shadish WR. Single-case intervention research design standards. Remedial Spec Educ. 2013;34:26–38. doi:10.1177/0741932512452794

- Horner RH, Carr EG, Halle J, McGee G, Odom S, Wolery M. The use of single subject research to identify evidence-based practice in special education. Except Child. 2005;71:165–79.

- Ferron J, Jones PK. Test for the visual analysis of response-guided multiple-base data. J Exp Educ. 2006;75:66–81. doi:10.3200/JEXE.75.1.66-81

- OCEBM. Levels of evidence working group. The Oxford levels of evidence 2. Oxford centre for evidence-based medicine; 2011 [cited 2019 Jun 23]. Available from: https://www.cebm.net/index.aspx?o=5653

- Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implemen Sci. 2010;5:69. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-5-69

- Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8:19–32. doi:10.1080/1364557032000119616

- The Joanna Briggs Institute. Joanna Briggs Institute reviewers’ manual: 2015 edition/supplement: the Joanna Briggs Institute; 2015. Available from: http://joannabriggs.org/assets/docs/sumari/Reviewers-Manual_Methodology-for-JBI-Scoping-Reviews_2015_v2.pdf

- Kratochwill TR, Hitchcock J, Horner RH, Levin JR, Odom SL, Rindskopf DM, Shadish, WR Single-case designs technical documentation. What Works Clearinghouse; 2010. Available from: https://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/Docs/ReferenceResources/wwc_scd.pdf

- Tate RL, Perdices M, Rosenkoetter U, Wakim D, Godbee K, Togher L, McDonald, S. Revision of a method quality rating scale for single-case experimental designs and n-of-1 trials: the 15-item risk of bias in N-of-1 trials (RoBiNT) scale. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2013;23:619–38. doi:10.1080/09602011.2013.824383

- Shamseer L, Sampson M, Bukutu C, Schmid CH, Nikles J, Tate R, Johnston BC, Zucker D, Shadish WR, Kravitz R, et al. CONSORT extension for reporting N-of-1 trials (CENT) 2015: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2015;350:h1793. doi:10.1136/bmj.h1793

- Akerstedt A, Risto O, Odman P, Oberg B. Evaluation of single event multilevel surgery and rehabilitation in children and youth with cerebral palsy–A 2-year follow-up study. Disabil Rehabil. 2010;32:530–39. doi:10.3109/09638280903180171

- Angelo J. Comparison of three computer scanning modes as an interface method for persons with cerebral palsy. Am J Occup Ther. 1992 official publication of the American Occupational Therapy Association;46:217–22. doi:10.5014/ajot.46.3.217

- Angelo J. Using single-subject design in clinical decision making: the effects of tilt-in-space on head control for a child with cerebral palsy. Assistive Technol. 1993;5:46–49. doi:10.1080/10400435.1993.10132206

- Barbosa AP, Vaz DV, Gontijo APB, Fonseca ST, Mancini MC. Therapeutic effects of electrical stimulation on manual function of children with cerebral palsy: evaluation of two cases. Disabil Rehabil. 2008;30:723–28. doi:10.1080/09638280701378902

- Beauregard R, Thomas JJ, Nelson DL. Quality of reach during a game and during a rote movement in children with cerebral palsy. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 1998;18:67–84. doi:10.1080/J006v18n03_05

- Brien M, Sveistrup H. An intensive virtual reality program impoves balance and functional mobility of adolescents with cerebral palsy. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;91:e45. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2010.07.161

- Brien M, Sveistrup H. An intensive virtual reality program improves functional balance and mobility of adolescents with cerebral palsy. Pediatr Phys Ther. 2011;23:258–66. doi:10.1097/PEP.0b013e318227ca0f

- Chen YP, Kang LJ, Chuang TY, Doong JL, Lee SJ, Tsai MW, Jeng SF, Sung WH. Use of virtual reality to improve upper-extremity control in children with cerebral palsy: a single-subject design. Phys Ther. 2007;87:1441–57. doi:10.2522/ptj.20060062

- Coker P, Lebkicher C, Harris L, Snape J. The effects of constraint-induced movement therapy for a child less than one year of age. Neuro Rehabili. 2009;24:199–208. doi:10.3233/NRE-2009-0469

- Corn K, Imms C, Timewell G, Carter C, Collins L, Dubbeld S, Schubiger S, Froude E. Impact of second skin lycra splinting on the quality of upper limb movement in children. Br J Occup Ther. 2003;66:464–72. doi:10.1177/030802260306601005

- Costigan FA, Light J. Effect of seated position on upper-extremity access to augmentative communication for children with cerebral palsy: preliminary investigation. Am J Occup Ther. 2010;64:596–604. doi:10.5014/ajot.2010.09013

- Crocker MD, MacKay-Lyons M, McDonnell E. Forced use of the upper extremity in cerebral palsy: a single-case design. Am J Occup Ther. 1997 official publication of the American Occupational Therapy Association;51:824–33. doi:10.5014/ajot.51.10.824

- Dada S, Alant E. The effect of aided language stimulation on vocabulary acquisition in children with little or no functional speech. Am J Speech-Lang Pathol. 2009;18:50–64. doi:10.1044/1058-0360(2008/07-0018)

- DeGangi GA, Hurley L, Linscheid TR. Toward a methodology of the short-term effects of neurodevelopmental treatment. Am J Occup Ther. 1983;37:479–84. doi:10.5014/ajot.37.7.479

- Dinomais M, Veaux F, Yamaguchi T, Richard P, Richard I, Nguyen S. A new virtual reality tool for unilateral cerebral palsy rehabilitation: two single-case studies. Dev Neurorehabil. 2013;16:418–22. doi:10.3109/17518423.2013.778347

- Do JH, Yoo EY, Jung MY, Park HY. The effects of virtual reality-based bilateral arm training on hemiplegic children’s upper limb motor skills. Neuro Rehabili. 2016;38:115–27. doi:10.3233/NRE-161302

- Durfee JL, Billingsley FF. A comparison of two computer input devices for uppercase letter matching. Am J Occup Ther. 1999 official publication of the American Occupational Therapy Association;53:214–20. doi:10.5014/ajot.53.2.214

- Fienup DM, Mudgal D, Pace G. Increasing money-counting skills with a student with brain injury: skill and performance deficits. Brain Inj. 2013;27:366–76. doi:10.3109/02699052.2012.743176

- Fragala MA, O’Neil ME, Russo KJ, Dumas HM. Impairment, disability, and satisfaction outcomes after lower-extremity botulinum toxin a injections for children with cerebral palsy. Pediatr Phys Ther. 2002;14:132–44. doi:10.1097/01.PEP.0000030091.82067.51

- Ghorbani N, Rassafiani M, Izadi-Najafabadi S, Yazdani F, Akbarfahimi N, Havaei N, Gharebaghy S. Effectiveness of cognitive orientation to (daily) occupational performance (CO-OP) on children with cerebral palsy: A mixed design. Res Dev Disabil. 2017;71:24–34. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2017.09.007

- Goodman G, Bazyk S. The effects of a short thumb opponens splint on hand function in cerebral palsy: a single-subject study. Am J Occup Ther. 1991 official publication of the American Occupational Therapy Association;45:726–31. doi:10.5014/ajot.45.8.726

- Hamill D, Washington K, White OR. The effect of hippotherapy on postural control in sitting for children with cerebral palsy. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 2007;27:23–42. doi:10.1080/J006v27n04_03

- Harris SR, Riffle K. Effects of inhibitive ankle-foot orthoses on standing balance in a child with cerebral palsy: A single-subject design. Phys Ther. 1986;66:663–67. doi:10.1093/ptj/66.5.663

- Hartveld A, Hegarty J. Frequent weightshift practice with computerised feedback by cerebral palsied children - Four single-case experiments. Physiotherapy. 1996;82:573–80. doi:10.1016/S0031-9406(05)66300-6

- Havstam C, Buchholz M, Hartelius L. Speech recognition and dysarthria: A single subject study of two individuals with profound impairment of speech and motor control. Logop Phoniatr Vocol. 2003;28:81–90. doi:10.1080/14015430310015372

- Hinderer KA, Harris SR, Purdy AH, Chew DE, Staheli LT, McLaughlin JF, Jaffe KM. Effects of ‘tone-reducing’ vs. standard plaster-casts on gait improvement of children with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1988;30:370–77.

- Iammatteo PA, Trombly C, Luecke L. The effect of mouth closure on drooling and speech. Am J Occup Ther. 1990 official publication of the American Occupational Therapy Association;44:686–91. doi:10.5014/ajot.44.8.686

- Jelsma J, Pronk M, Ferguson G, Jelsma-Smit D. The effect of the Nintendo Wii Fit on balance control and gross motor function of children with spastic hemiplegic cerebral palsy. Dev Neurorehabil. 2013;16:27–37. doi:10.3109/17518423.2012.711781

- Johnson BA, Salzberg C, MacWilliams BA, Shuckra AL, D’Astous JL. Plyometric training: effectiveness and optimal duration for children with unilateral cerebral palsy. Pediatr Phys Ther. 2014;26:169–79. doi:10.1097/PEP.0000000000000012

- Kelly ME, Darrah J, Sobsey R, Haykowsky M, Legg D. Effects of a community-based aquatic exercise program for children with cerebral palsy: a single subject design. J Aquat Phys Ther. 2009;17:1–11.

- Kenyon LK, Farris JP, Aldrich NJ, Rhodes S. Does power mobility training impact a child’s mastery motivation and spectrum of EEG activity? An exploratory project. Disability Rehabili. 2018;13:665–73. doi:10.1080/17483107.2017.1369587.

- Kinghorn J, Roberts G. The effect of an inhibitive weight-bearing splint on tone and function: a single-case study. Am J Occup Ther. 1996 official publication of the American Occupational Therapy Association;50:807–15. doi:10.5014/ajot.50.10.807

- Ko MS, Lee JA, Kang SY, Jeon HS. Effect of Adeli suit treatment on gait in a child with cerebral palsy: a single-subject report. Physiother Theory Pract. 2015;31:275–82. doi:10.3109/09593985.2014.996307

- Laessker-Alkema K, Eek MN. Effect of knee orthoses on hamstring contracture in children with cerebral palsy: multiple single-subject study. Pediatr Phys Ther. 2016;28:347–53. doi:10.1097/PEP.0000000000000267

- Lammi BM, Law M. The effects of family-centred functional therapy on the occupational performance of children with cerebral palsy. Can J Occup Ther. 2003;70:285–97. doi:10.1177/000841740307000505

- Laskas CA, Mullen SL, Nelson DL, Willson-Broyles M. Enhancement of two motor functions of the lower extremity in a child with spastic quadriplegia. Phys Ther. 1985;65:11–16. doi:10.1093/ptj/65.1.11

- Lephart K, Kaplan SL. Two seating systems’ effects on an adolescent with cerebral palsy and severe scoliosis. Pediatr Phys Ther. 2015;27:258–66. doi:10.1097/PEP.0000000000000163

- Lewis J, Pin T. Dynamic elastomeric fabric orthosis in managing shoulder subluxation in children with severe cerebral palsy: A case series. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2016;58:61.

- Lilly LA, Powell NJ. Measuring the effects of neurodevelopmental treatment on the daily living skills of 2 children with cerebral palsy. Am J Occup Ther. 1990 official publication of the American Occupational Therapy Association;44:139–45. doi:10.5014/ajot.44.2.139

- Lin CY, Chang YM. Increase in physical activities in kindergarten children with cerebral palsy by employing MaKey-MaKey-based task systems. Res Dev Disabil. 2014;35:1963–69. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2014.04.028

- Lin CY, Chang YM. Interactive augmented reality using Scratch 2.0 to improve physical activities for children with developmental disabilities. Res Dev Disabil. 2015;37:1–8. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2014.10.016

- Mackey S. The use of computer-assisted feedback in a motor control task for cerebral palsied children. Physiotherapy. 1989;75:143–48. doi:10.1016/S0031-9406(10)62767-8

- Man DW, Wong MS. Evaluation of computer-access solutions for students with quadriplegic athetoid cerebral palsy. Am J Occup Ther. 2007 official publication of the American Occupational Therapy Association;61:355–64. doi:10.5014/ajot.61.3.355

- Matthews MJ, Watson M, Richardson B. Effects of dynamic elastomeric fabric orthoses on children with cerebral palsy. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2009;33:339–47. doi:10.3109/03093640903150287

- McCarthy JH, Hogan TP, Beukelman DR, Schwarz IE. Influence of computerized sounding out on spelling performance for children who do and do not rely on AAC. Disabil Rehabil. 2015 Assistive technology;10:221–30. doi:10.3109/17483107.2014.883650

- McConnell K, Johnston L, Kerr C. Efficacy and acceptability of reduced intensity constraint-induced movement therapy for children aged 9–11 years with hemiplegic cerebral palsy: a pilot study. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 2014;34:245–59. doi:10.3109/01942638.2013.866611

- Owen SE, Stern LM. Management of drooling in cerebral palsy: three single case studies. Int J Rehabil Res. 1992;15:166–69.

- Pinder GL, Olswang LB. Development of communicative intent in young children with cerebral palsy: a treatment efficacy study. Infant-Toddler Intervention. 1995;5:51–69.

- Pool D, Blackmore AM, Bear N, Valentine J. Effects of functional electrical stimulation in children with spastic hemiplegia. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2014;56:9–10. doi:10.1111/dmcn.12296

- Pool D, Blackmore AM, Bear N, Valentine J. Effects of short-term daily community walk aide use on children with unilateral spastic cerebral palsy. Pediatr Phys Ther. 2014;26:308–17. doi:10.1097/PEP.0000000000000057

- Pratt B, Hartshorne NS, Mullens P, Schilling ML, Fuller S, Pisani E. Effect of playground environments on the physical activity of children with ambulatory cerebral palsy. Pediatr Phys Ther. 2016;28:475–82. doi:10.1097/PEP.0000000000000318

- Prosser LA, Ohlrich LB, Curatalo LA, Alter KE, Damiano DL. Feasibility and preliminary effectiveness of a novel mobility training intervention in infants and toddlers with cerebral palsy. Dev Neurorehabil. 2012;15:259–66. doi:10.3109/17518423.2012.687782

- Prosser LA, Ohlrich L, Curatalo L, Alter K, Damiano D. Novel mobility training in prewalking toddlers with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2012;54:23. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8749.2012.04387.x.

- Ramani KK, Police SR, Jacob N. Impact of low vision care on reading performance in children with multiple disabilities and visual impairment. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2014;62:111–15. doi:10.4103/0301-4738.111207

- Ray SA, Bundy AC, Nelson DL. Decreasing drooling through techniques to facilitate mouth closure. Am J Occup Ther. 1983;37:749–53. doi:10.5014/ajot.37.11.749

- Reid D, Rigby P, Ryan S. Functional impact of a rigid pelvic stabilizer on children with cerebral palsy who use wheelchairs: users’ and caregivers’ perceptions. Pediatr Rehabil. 1999;3:101–18. doi:10.1080/136384999289513.

- Retarekar R, Fragala-Pinkham MA, Townsend EL. Effects of aquatic aerobic exercise for a child with cerebral palsy: single-subject design. Pediatr Phys Ther. 2009;21:336–44. doi:10.1097/PEP.0b013e3181beb039

- Rigby P, Reid D, Schoger S, Ryan S. Effects of a wheelchair-mounted rigid pelvic stabilizer on caregiver assistance for children with cerebral palsy. Assistive Technol. 2001;13:2–11. doi:10.1080/10400435.2001.10132029

- Rintala P, Era P. Posture control in children with cerebral palsy; a pilot study. J Rehabil Sci. 1994;7:9–14.

- Rivi E, Filippi M, Fornasari E, Mascia MT, Ferrari A, Costi S. Effectiveness of standing frame on constipation in children with cerebral palsy: a single-subject study. Occup Ther Int. 2014;21:115–23. doi:10.1002/oti.1370

- Sakemiller LM, Nelson DL. Eliciting functional extension in prone through the use of a game. Am J Occup Ther. 1998 official publication of the American Occupational Therapy Association;52:150–57. doi:10.5014/ajot.52.2.150

- Sheppard L, Mudie H, Froude E. An investigation of bilateral isokinematic training and neurodevelopmental therapy in improving use of the affected hand in children with hemiplegia. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 2007;27:5–25. doi:10.1080/J006v27n01_02.

- Shumway-Cook A, Hutchinson S, Kartin D, Price R, Woollacott M. Effect of balance training on recovery of stability in children with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2003;45:591–602.

- Siconolfi-Morris GC. Use of a video game based balance training intervention on the balance and function of children with developmental disabilities [dissertation]. Lexington (KY): University of Kentucky; 2012.

- Smelt HR. Effect of an inhibitive weight-bearing mitt on tone reduction and functional performance in a child with cerebral palsy. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 1989;9:53–80.

- Smithers JA. Facilitation of rolling in a child with athetoid cerebral palsy - A single-subject design. Physiotherapy. 1991;77:243–48. doi:10.1016/S0031-9406(10)61742-7

- Soto G, Yu B, Kelso J. Effectiveness of multifaceted narrative intervention on the stories told by a 12-year-old girl who uses AAC. Augment Altern Commun. 2008;24:76–87. doi:10.1080/07434610701740612

- Stansfield S, Dennis C, Larin H, Gallagher C. Movement-based VR gameplay therapy for a child with cerebral palsy. Annu Rev CyberTher Telemedicine. 2015;13:153–57.

- Stewart H, Noble G, Seeger BR. Isometric joystick: A study of control by adolescents and young adults with cerebral palsy. Aust Occup Ther J. 1992;39:33–39. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1630.1992.tb01733.x

- Stewart H, Wilcock A. Improving the communication rate for symbol based, scanning voice output device users. Technol Disability. 2000;13:141–50. doi:10.3233/TAD-2000-13301

- Svedberg LE, Nordahl UE, Lundeberg TC. Effects of acupuncture on skin temperature in children with neurological disorders and cold feet: an exploratory study. Complement Ther Med. 2001;9:89–97. doi:10.1054/ctim.2001.0436

- Symons FJ, Tervo RC, Kim O, Hoch J. The effects of methylphenidate on the classroom behavior of elementary school-age children with cerebral palsy: A preliminary observational analysis. J Child Neurol. 2007;22:89–94. doi:10.1177/0883073807299965

- Thorpe DE, Valvano J. The effects of knowledge of performance and cognitive strategies on motor skill learning in children with cerebral palsy. Pediatr Phys Ther. 2002;14:2–15.

- Ustad T, Sorsdahl AB, Ljunggren AE. Effects of intensive physiotherapy in infants newly diagnosed with cerebral palsy. Pediatr Phys Ther. 2009;21:140–49. doi:10.1097/PEP.0b013e3181a3429e

- Voulgarakis H, Forte S. Escape extinction and negative reinforcement in the treatment of pediatric feeding disorders: A single case analysis. Behav Anal Pract. 2015;8:212–14. doi:10.1007/s40617-015-0086-8

- Ward R, Leitao S, Strauss G. An evaluation of the effectiveness of PROMPT therapy in improving speech production accuracy in six children with cerebral palsy. Int J Speech Lang Pathol. 2014;16:355–71. doi:10.3109/17549507.2013.876662

- Ward R, Strauss G, Leitao S. Kinematic changes in jaw and lip control of children with cerebral palsy following participation in a motor-speech (PROMPT) intervention. Int J Speech Lang Pathol. 2013;15:136–55. doi:10.3109/17549507.2012.713393

- Michiels B, Onghena P. Randomized single-case AB phase designs: prospects and pitfalls. Behav Res Methods. 2018. doi:10.3758/s13428-018-1084-x

- Tate RL, McDonald S, Perdices M, Togher L, Schultz R, Savage S. Rating the methodological quality of single-subject designs and n-of-1 trials: introducing the Single-Case Experimental Design (SCD) scale. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2008;18:385–401. doi:10.1080/09602010802009201

- Tate RL, Perdices M, Rosenkoetter U, Shadish W, Vohra S, Barlow DH, Horner R, Kazdin A, Kratochwill T, McDonald S, et al. The Single-Case Reporting Guideline In BEhavioural Interventions (SCRIBE) 2016 statement. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2017;27:1–15. doi:10.1080/09602011.2016.1190533

- Romeiser Logan L, Hickman RR, Harris SR, Heriza CB. Single-subject research design: recommendations for levels of evidence and quality rating. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2008;50:99–103. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8749.2007.02005.x

Appendix 1.

Search query

EMBASE database (Ovid interface)

1. Cerebral Palsy/

2. ((cerebral or brain or central) adj2 (pals$ or paraly$)).ti,ab,ot.

3. 1 or 2

4. Infant/or exp Child/or Adolescent/or Young Adult/or Pediatrics/

5. (infant$ or child$ or adolescent$ or p?ediatric$ or youth).ti,ab,ot.

6. 4 or 5

7. (“n of 1” or “single subject$” or “single case$” or “single patient$” or “within subject$”).ti,ab,ot.

8. 3 and 6 and 7

9. limit 8 to humans

10. remove duplicates from 9

MEDLINE database (Ovid interface)

#1 Cerebral Palsy[mesh:noexp]

#2 ((cerebral[tiab] OR brain[tiab] OR central[tiab]) AND (pals*[tiab] OR paraly*[tiab]))

#3 (#1 OR #2)

#4 (Infant[mesh:noexp] OR Child[mesh] OR Adolescent[mesh:noexp] OR Young Adult[mesh:noexp] OR Pediatrics[mesh:noexp])

#5 (infant*[tiab] OR child*[tiab] OR adolescent*[tiab] OR pediatric*[tiab] OR paediatric*[tiab] OR youth[tiab])

#6 (#4 OR #5)

#7 (“n-of-1*”[tiab] OR “single subject*”[tiab] OR “single case*”[tiab] OR “single patient*”[tiab] OR “within subject*”[tiab])

#8 (#3 AND #6 AND #7)

CINAHL and PsycINFO databases (EBSCO interface)

S1 MH “Cerebral Palsy”

S2 TI (cerebral OR brain OR central) N2 (pals* OR paraly*) OR AB (cerebral OR brain OR central) N2 (pals* OR paraly*)

S3 S1 OR S2

S4 MH “Infant” OR MH “Child, Preschool” OR MH “Child” OR MH “Adolescence” OR MH “Young Adult” OR MH “Pediatrics”

S5 TI (infant* OR child* OR adolescent* OR p#ediatric* OR youth) OR AB (infant* OR child* OR adolescent* OR p#ediatric* OR youth)

S6 S4 OR S5

S7 TI (“n-of-1*” OR “single subject*” OR “single case*” OR “single patient*” OR “within subject*”) OR AB (“n-of-1*” OR “single subject*” OR “single case*” OR “single patient*” OR “within subject*”)

S8 S3 AND S6 AND S7