ABSTRACT

Background

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for psychosis (CBTp) is recommended by psychosis treatment guidelines in the U.S. and Canada, however accessibilty has not been systematically established and little is known about trainer or training characteristics in these countries. This paper represents the first effort to estimate the population of CBTp practitioners, characterize trainer qualifications and training practices, and calculate a CBTp accessibility estimate.

Methods

We oversampled from a known cluster of the target population and supplemented with chain-referral sampling. Respondents completed an online survey pertaining to workforce training conducted since 2005. An accessibility estimate was calculated using published disease prevalence data and national workforce census data.

Results

Twenty-five CBTp trainers completed the questionnaire. Respondents were predominantly white female psychologists in hospital or academic settings. Their estimates of practitioners trained in the past 15 years yielded a point prevalence of 0.57% of the combined mental health workforce, corresponding to 11.5–22.8 CBTp-trained providers for every 10,000 people diagnosed with a psychotic disorder. Survey results showed several differences in training approaches, settings, and funders.

Discussion

This preliminary study suggests that CBTp remains inaccessible across these two countries. Future studies should refine the sampling methods to provide a more robust prevalence estimate within each country.

Introduction

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for psychosis (CBTp) is regarded as an evidence-based psychotherapy with both stable and sufficient evidence for treating psychotic and mood symptoms, reducing hospitalization, and reducing the disability associated with a schizophrenia spectrum disorders (Gould et al., Citation2001; McDonagh et al., Citation2018; Pilling et al., Citation2002; Turner et al., Citation2020; Wykes et al., Citation2008; Zimmermann et al., Citation2005). CBTp is included in the national schizophrenia practice guidelines in the U.S. and Canada (American Psychiatric Association [APA], Citation2020; Norman et al., Citation2017), and studies suggest that CBTp is in demand among service users (Wood et al., Citation2015) and their families (S. Kopelovich et al., Citation2021). Unfortunately, anecdotal accounts unequivocally decry the inaccessibility of CBTp. Empirically, little is known about the extent to which CBTp is accessible in the U.S. or Canada, nor has there been an investigation into the training methods or qualifications of CBTp trainers in these regions. Upon an extensive review of the literature, we only identified one systematic attempt to assess the penetration of CBTp training in the U.S. Kimhy et al. (Citation2013) surveyed training directors in U.S. psychiatry residency and clinical psychology doctoral programs. Although 45% responded that their program offered CBTp training, they found heterogeneity in depth and breadth of the training. Respondents reported a mean of 4.1 hours of CBTp didactic training (SD = 3.3), 21.8 hours of face-to-face CBTp treatment (SD = 37.8) and 12.3 hours of supervision (SD = 19.2). To our knowledge, the only estimate of the prevalence of CBTp-trained practitioners in the American workforce is an unpublished account prepared for the Association of Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies (ABCT) annual conference, for which Mueser et al. (Citation2015) estimated that 0.1% of the U.S. mental health workforce had been trained in CBTp treatment delivery. The accuracy of this estimate is unknown, as it was generated using informal polling of an unknown number of CBTp trainers (K. Mueser, personal communication, 20 November 2018). In light of the recent proclamation by the U.S. federal government (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], Citation2021) and Canadian provincial governments (Health Quality Ontario, Citation2016) that CBTp should be standard of care, there is a clear need to systematically study its accessibility in the public sector.

Countries outside of North America that include CBTp in national treatment guidelines acknowledge that clinical practice poorly aligns with the recommendation to treat psychotic disorders with CBTp. In Great Britain, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines establish that all service users are offered CBTp within 7 days of a psychotic disorder diagnosis. Estimates of CBTp penetration in Great Britain have been widely divergent. Colling et al. (Citation2017) estimated that 35% of individuals with a diagnosed psychotic disorder have accessed CBTp (operationalized as having received at least one session). The authors derive this estimate on the basis of an extensive audit of cross-sectional samples of electronic health records from thousands of service users with psychosis. This audit method yielded higher estimates of CBTp administration than a previously reported manual audit from the same trust (34.6% versus 6.4%; Haddock et al., Citation2014). Colling et al.’s estimate is tempered by the fact that, within the trust from which they sampled, the majority of residents diagnosed with a schizophrenia spectrum disorder are served by psychosis specialty care teams. Multidisciplinary care teams that primarily serve individuals with psychotic disorders are more likely to offer a psychotherapeutic intervention for psychosis than adult outpatient settings (Bird et al., Citation2010). A more geographically expansive audit, the National Audit of Schizophrenia (NAS2; Royal College of Psychiatrists, Citation2014), estimated that 39% of service users had been offered CBTp, 19% had agreed to receive CBTp, and 18% had reported that they had actually received CBTp in trusts across the United Kingdom.

Less research has been conducted on the accessibility of CBTp in other countries. One investigation in Australia surveyed clinical staff from two metropolitan mental health service regions (Dark et al., Citation2015). Although estimating the prevalence of CBTp-trained staff was a peripheral aim of their investigation, they found that 24% of mental health providers in these two regions had been trained in CBTp, with 14% identifying as CBT therapists. A critical caveat that limits generalizability of these findings is that the study was limited to regional healthcare organizations that had already embarked on deliberate efforts to adopt evidence-based therapies for individuals with serious mental illness (SMI), including CBTp implementation. We would therefore expect that the penetration of CBTp in these service regions would be higher than in regions that had not yet committed to enhancing access to evidence-based treatments for residents with SMI. An earlier and far more comprehensive Australian survey of approximately 2,000 individuals who had screened positive for psychosis across seven geographic regions found CBT to be one of the most commonly accessed therapies at 22.3% (Morgan et al., Citation2012). These findings were derived from the Survey of High Impact Psychosis (SHIP), a multi-site and multi-sponsor prospective longitudinal cross-sectional study.

The pronounced discrepancy between the identified need for CBTp and its availability in the community compels us to systematically estimate the number of CBTp-trained practitioners in the behavioral health workforce in the U.S. and Canada – two high-income North American countries for which CBTp is intended to be the clinical standard of care. Unfortunately, the decentralized nature of the public behavioral health system in these countries makes systematic audits and other forms of national prevalence estimates both financially and logistically prohibitive. To date, no systematic estimation of the CBTp training workforce in the U.S. or Canada have been published, nor do we have published accounts of the means by which mental health professionals become trained to conduct CBTp trainings or the standard components of CBTp training programs. A preliminary investigation of these questions that is both pragmatic and cost-effective is an important step toward understanding the challenges these countries face in consistent and equitable delivery of CBTp.

Methods

Study design and sample population

The North American CBTp Network (NACBTpN) was formed in 2015 as a professional organization by and for CBTp scholars, practitioners, and trainers committed to broader access to evidence-based CBTp training across North America. Membership in this organization is available to individuals interested in CBTp with license-eligible degrees in clinical mental health or related fields. This preliminary point-prevalence survey was conducted in consultation with the 11-person Steering Committee of the NACBTpN, of which the first author is a member. Steering Committee members were given the opportunity to review and suggest edits to the methodology and questionnaire. Because the sampling universe is smaller for CBTp trainers than CBTp-trained practitioners, and because CBTp trainers are more easily identified, we targeted trainers for our sampling frame. Further, as there is no CBTp practitioner database or credentialing body in either country, we used the NACBTpN listserv as our primary source of recruitment. All NACBTpN members (N = 32) were invited to participate through an announcement sent to the NACBTpN listserv. Because many trainers incorporate a Train-the-Trainer model or are professionally connected to eligible practitioners who are not members of the NACBTpN, we also relied on chain-referral sampling (Thompson & Frank, Citation2000), in which NACBTpN members were asked to forward the questionnaire to colleagues or trainees who may now be training others in CBTp. This method has been found to be well-suited for sampling from small populations (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine [NASEM], Citation2018).

Respondents first completed a 2-item screener inquiring whether they have been trained in CBTp and whether they are a CBTp trainer. For the purposes of this study, CBTp was defined as a talk therapy that includes at least one of the following components: (a) self-monitoring of thoughts, feelings, or behaviors about the service user’s symptoms/symptom recurrence; (b) promoting alternative ways to cope with target symptom(s); (c) reducing psychotic-related distress; or (d) improving functioning. This definition is consistent with both National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE, Citation2015) and APA (Citation2020) treatment guidelines. A CBTp trainer was defined as a CBTp practitioner who has, in the past 15 years, trained other mental health practitioners in CBTp with the express aim that trainees will be able to deliver the intervention to clients. Only those who endorsed meeting those operational criteria were invited to proceed to the questionnaire. Responses were confidential, and no identifying information was required. The survey was open for 14 weeks, and reminder emails were sent to the NACBTpN listserv 3-, 7-, and 13-weeks after the initial email. No compensation was provided to complete the online questionnaire, which took approximately 15 minutes to complete. This study was approved by the University of Washington Institutional Review Board.

Measures

The questionnaire consisted of 24 forced-choice items and 19 open-field questions to permit participants to further explain “yes” or “other” responses. After demographic information, participants were asked about their own training and the training they provide to others. Training questions assessed primary training methods employed, funding sources, and characteristics of trainees and training settings. Participants were also guided to estimate the total number of people they have trained, the disciplines and work settings of the providers they have trained, and the number of clients to whom trainees administer CBTp annually, if known.

Data analysis

Study data were collected and managed using REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture; Harris et al., Citation2019, Citation2009), which is a secure, web-based software platform designed to support data capture for research studies and analyzed with Stata 16 statistical analysis software. Because the aims of this study were hypothesis generating versus hypothesis testing, data was analyzed using descriptive statistics and by searching for common themes in open-ended responses. To calculate the prevalence of CBTp-trained mental health providers in the U.S. and Canada, we calculated the sum of the survey respondents who reported that they currently provide CBTp and total number of providers each respondent reported training in the past 15 years to calculate the numerator. The total number of licensed practitioners eligible to administer CBTp was calculated using U.S. and Canadian government employment data for mental health provider occupations that treat individuals with SMI. We estimated the accessibility of CBTp by persons with psychotic disorders by calculating the number of CBTp-trained mental health providers in the U.S. and Canada per 10,000 people with psychotic disorders in these countries. We used our estimated total of CBTp-trained mental health providers for this calculation as well. The number of people with psychotic disorders in the U.S. and Canada was ascertained by using prevalence estimates from national comorbidity studies from each country. Because there are discrepancies about the prevalence of psychotic disorders, we report ranges rather than a precise estimate.

Results

Sample characteristics

Twenty-five people qualified to complete the survey. The demographics of the sample are reported in . We were interested in ascertaining how CBTp trainers acquired their own training and experience in CBTp (). Most respondents (72%) selected two or more types of training, 48% selected three or more options, and 36% selected four or more options. All respondents who endorsed being self-trained (n = 12) also endorsed another form of training.

Table 1. Sample demographics.

Nearly all respondents (96%) reported that they currently practice CBTp. Amongst all respondents, 60% have at some point received fidelity reviews on their own CBTp sessions, 64% have at some point received expert supervision on their CBTp practice, 48% have received both fidelity reviews and expert supervision, and 20% have received neither fidelity reviews nor expert supervision. Only 3 respondents (12%) currently receive fidelity reviews on their CBTp sessions; of those, 1 receives them every 6 months or less, 1 receives them every 6–12 months, and 1 receives them every 1 to 2 years.

Primary aim: point prevalence estimate of CBTp providers

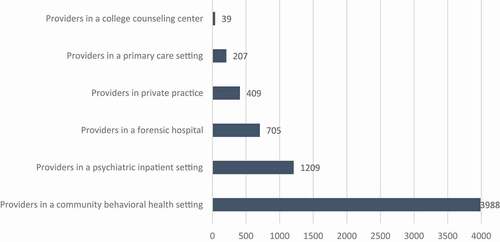

Respondents were asked to estimate the total number of providers in the U.S. or Canadian workforce that they had trained in CBTp since 2005. All respondents have trained others in CBTp in the past 15 years; 20 respondents (80%) were actively training in the year they completed the survey. Five respondents (20%) indicated that they are not currently training others in CBTp and did not provide an estimate of the number of providers they have trained. The 20 respondents who did indicate they are currently training others in CBTp estimated that they trained a total of 6,900 providers in CBTp in the past 15 years (see ). One respondent reported they were not currently administering CBTp to their clients. Including the 24 respondents who currently practice CBTp, the estimate of providers trained is 6,924 in the U.S. and Canada.

To estimate the point prevalence of the mental health workforce in the U.S. and Canada who are trained in CBTp, we obtained employment numbers by profession from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) Occupational Employment Statistics (OES) for the U.S. workforce and from the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) for the Canadian workforce. We included only those professions that commonly treat patients with psychotic disorders to calculate the base mental health workforce population. The U.S. mental health workforce consists of 1,126,870 mental professionals that are qualified to treat individuals with a mental illness (Bureau of Labor Statistics [BLS], Citation2019). This figure consists of 1,013,600 counselors, social workers, and other community and social service specialists; 25,530 psychiatrists; and 113,270 clinical, counseling, and school psychologists. It excludes disciplines that are not credentialed to provide psychotherapy to individuals with mental illness (e.g. Health Education Specialists; Social and Human Service Assistants; Educational, Guidance, and Career Counselors and Advisors). Based on the most recent estimates available, the Canadian mental health workforce includes 54,269 social workers, 19,171 psychologists, and 5,263 psychiatrists in the publicly funded health care system (total qualifying MH workforce = 78,703; Canadian Institute for Health Information [CIHI], Citation2019). With this combined mental health workforce of 1,231,103, we estimate that 0.57% of the U.S. and Canadian mental health workforce were trained in CBTp between 2005 and 2020.

In the U.S., prevalence of schizophrenia spectrum disorders is estimated to be between 0.8% and 1.6% of the U.S. population, (American Psychiatric Association [APA], Citation2013; Bourdon et al., Citation1992; Kessler et al., Citation2005) or 2,625,600–5,251,200 people (United States Census Bureau, Citation2019). In Canada, prevalence of schizophrenia spectrum disorders is estimated to be between 1.1% and 2.1%, (APA, Citation2013; Hafner & Heiden, Citation1997; Vanasse et al., Citation2012) or 413,600–789,600 people, yielding a combined estimate of 3,039,200–6,040,800 of individuals with a primary psychotic disorder across both countries (Statistics Canada, Citation2019). Based on these data, we estimate there are 11.5–22.8 CBTp-trained providers for every 10,000 people with a primary psychotic disorder in the U.S. and Canada.

Characteristics of trainers and training methods

A majority of respondents indicated that they have conducted trainings in a hospital setting (75%), community behavioral health centers (70%), university settings (60%), and medical schools (55%). Private practitioner trainings are far less common (15%). Trainees practiced in an array of clinical settings; a breakdown of the total number trained by professional setting can be found in .

Trainings conducted by respondents varied in their protocols, approaches, and funded sources. There are a variety of evidence-based CBTp protocols and modalities, including formulation-based individual CBTp, group-administered CBTp, symptom-specific (e.g. command auditory hallucination) CBTp, and CBTp-informed care. For this survey, individual CBTp was broken down into two types: manualized CBTp and non-manualized formulation-driven CBTp. Most respondents (68.4%) train to more than one type of CBTp (). Formulation-driven CBTp and CBTp-informed care were the most commonly endorsed types of CBTp training provided.

Table 2. Protocol used in CBTp training.

Most trainers in our sample require their trainees to complete an in-person, instructor-led workshop (86.4%) as well as supervision or consultation sessions (90.9%). The mean workshop length was 2.5 days (range = 1–4 days, SD = 0.75). Three respondents required trainees to complete an online course in CBTp, with course lengths ranging from 1- to 36-hours. Roughly two-thirds (68.2%) require their trainees to submit to fidelity reviews of CBTp sessions as a component of their CBTp training. Respondents who require fidelity reviews required that trainees complete a fidelity review in an average of 72% (SD = 29.7) of their trainings, with a range of 20–100%. Of those respondents who mandate fidelity reviews, 84.6% require their trainees to complete a minimum number of reviews above competency, with an average of 3.4 reviews for each trainee (SD = 1.9, range = 1–6). The most common fidelity tool used by respondents are the Revised Cognitive Therapy Scale (CTS-R; 40.0%), the Revised Cognitive Therapy for Psychosis Adherence Scale (R-CTPAS; 40.0%), and the Cognitive Therapy Rating Scale (CTR-S; 33.3%). Two respondents reported using a newly developed, unpublished rating form. Only two respondents are systematically assessing CBTp fund of knowledge. Finally, respondents reported a variety of funders for their trainings. Of those who reported they are currently training other, 63.7% reported that they received funding from more than one source. shows a breakdown of funding sources.

Table 3. Funding sources for trainings conducted by respondents.

Discussion

CBTp is recommended by national treatment guidelines in the U.S. and Canada and is the most well-researched psychotherapeutic intervention for psychotic disorders (Barbieri & Visco-Comandini, Citation2019; Gould et al., Citation2001; Kuipers et al., Citation1998; Pilling et al., Citation2002; Wykes et al., Citation2008; Zimmermann et al., Citation2005). Although adoption in North America has lagged behind the United Kingdom – the official birthplace of CBTp – it has received a great deal more attention in the U.S. and Canada since Mueser and Noordsy’s (Citation2005) call to action, which encouraged CBTp practice to better align with the evidence base and treatment guidelines. At the time the NACBTpN was formed, founding members estimated the prevalence of CBTp-trained practitioners in the U.S. as roughly 0.1% of the mental health workforce (Mueser et al., Citation2015). The preliminary study we conducted serves as the first point-prevalence estimate of CBTp-trained providers in U.S. and Canada, conducted to establish a more reliable indicator of CBTp penetration. Our preliminary prevalence estimate of 0.57% supports anecdotal observations by mental health system stakeholders that there is very poor penetration of CBTp training among mental health providers. We estimate that there are 11.5–22.8 CBTp-trained providers for every 10,000 people with a psychotic disorder in the U.S. and Canada, suggesting that CBTp remains largely inaccessible in these countries. The COVID-19 pandemic may have increased access to CBTp training and reduced costs associated with in-person workshops. However, our data suggests that institutional contracts at community behavioral agencies were the most commonly reported source of funding, suggesting that implementation in the U.S. and Canada is occurring at an individual rather than population level. This stands in contrast with countries like Great Britain, which has implemented a top-down approach to training within and across the healthcare system and for which access to CBTp or CBTp-informed care is more common.

Training received by the CBTp trainers we surveyed varied considerably, with respondents endorsing having received, on average, between 2–3 types of training. Interestingly, not all of the respondents have received fidelity reviews of their own CBTp sessions. Fidelity reviews assess the extent to which an individual’s session is adherent to the EBT model and the degree of competency in executing components of the intervention. Presumably, fidelity reviews provide some degree of assurance that the trainer’s own clinical practices are rated as model consistent by their peers. Roughly one-third of respondents identified as “self-trained”, which may further indicate a dearth of available training, even among doctoral-level practitioners (Kimhy et al., Citation2013).

The most common setting in which CBTp trainings are occurring are community mental health centers, which often offer treatment to individuals with limited access to medical services. While training in community health centers may increase accessibility, a lack of CBTp training in academic training institutions implies that this treatment is not part of the general education for providers. This may also imply that providers or workplaces looking to implement CBTp may have to seek it out, which first requires knowledge of the treatment, knowledge of where to find trainers, and funding to host or attend trainings.

Funding for respondents’ trainings was provided primarily through organizational contracts or trainings were conducted by staff CBTp trainers, with government contracts, grants, and private pay comprising a minority of funding mechanisms. Improving access to CBTp will require greater consistency in and opportunity for CBTp training and ongoing sustainment efforts. Indeed, given high rates of turnover in community mental health and ongoing need for quality monitoring, state, provisional, or regional government funding for CBTp Intermediary/Purveyor Organizations (IPOs) can help to advance CBTp training, implementation, and long-term sustainment.

Our survey revealed heterogeneity both in the training strategies employed and in the methods used to assess knowledge and functional competencies. A greater proportion of our sample reported requiring fidelity reviews of trainees than having received a fidelity review themselves. Although it is the case that not all respondents are engaging in standardized quality monitoring, it should be noted that this does not discount the possibility that they are engaging in other forms of performance-based feedback, such as role plays during training or consultation sessions. Certification standards for CBTp are currently under review and, once codified, will likely alter current practices.

Limitations and future directions

This preliminary point prevalence study had several limitations. In lieu of a census- or audit-based estimate employed in the United Kingdom and Australia, we used chain-referrals as a convenience sampling method common to inaccessible populations (NASEM, Citation2018). Because convenience samples are non-probability based and introduce multiple sources of bias, our findings should be interpreted with caution as our small sample may not be representative of the reference population. We intentionally oversampled a cluster of mental health professionals within a professional organization devoted to advancing high-quality CBTp in the U.S. and Canada. It is possible that the training credentials and training features reported by our sample are not representative of other CBTp trainers. We also cannot discount demand characteristics and recall error, which may have contributed to inaccuracies in respondents’ reporting. Our statistical inferences may be compromised in terms of precision because of the small sample and the inclusion only of those practitioners who are licensed and captured by national workforce census estimates. Respondents’ locations and the locations of their trainings were not able to be accurately accounted for, which impeded point-prevalence estimates for each country. Given that these two countries have different health care systems, policies, and payment models, the prevalence estimate we generated should be treated as preliminary at best. Our accessibility estimate also fails to account for the fact that not all providers who were trained in CBTp are providing CBTp. Given high rates of turnover of behavioral health staff in the public sector (Hyde, Citation2013; Paris & Hoge, Citation2010) and low rates of EBT delivery following a training (Beidas & Kendall, Citation2010; Damschroder et al., Citation2009), it is possible that CBTp accessibility is even lower than our projections would imply.

More rigorous respondent-driven sampling of service users with psychotic disorders in each of the respective countries is needed to better ascertain CBTp penetration in these countries. Nevertheless, our sobering findings, which are comparable to the rough estimate previously generated (Mueser et al., Citation2015), suggest that the call to action issued by psychosis intervention researchers nearly 20 years ago (Mueser & Noordsy, Citation2005) and echoed now by the federal government (SAMHSA, Citation2021) and professional bodies (S. L. Kopelovich et al., Citation2021) have gone unheeded. The full extent of this issue has been severely under studied. Without an attempt to quantify the prevalence of CBTp trainers and penetration of the intervention in North America, resources aimed at redressing this issue cannot be properly allocated. Although preliminary, this is the first known study to systematically estimate the point prevalence of CBTp-trained clinicians in North America or to assess the qualifications and practices of the currently unregulated market of CBTp trainers. This study serves to lay groundwork in our understanding of the dearth of evidence-based psychotherapy for psychosis in these North American countries from which other studies may build.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to express gratitude to Steering Committee of the North America Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Psychosis Network who provided early input on study methodology and the questionnaire: Faye Doell, PhD; Kate Hardy, Clin.Psych.D, Tania Lecomte, PhD; Mahesh Manon, PhD; Sally Riggs, D.Clin.Psy., and Nicola Wright, PhD.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

- American Psychiatric Association. (2020). The American psychiatric association practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia. American Psychiatric Pub. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890424841

- Barbieri, A., & Visco-Comandini, F. (2019). Efficacy of cognitive behavioural therapy in the treatment of psychosis: A meta-review. Rivista di Psichiatria, 54(5), 189–195. https://doi.org/10.1708/3249.32182

- Beidas, R. S., & Kendall, P. C. (2010). Training therapists in evidence‐based practice: A critical review of studies from a systems‐contextual perspective. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 17(1), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2850.2009.01187.x

- Bird, V., Premkumar, P., Kendall, T., Whittington, C., Mitchell, J., & Kuipers, E. (2010). Early intervention services, cognitive–behavioural therapy and family intervention in early psychosis: Systematic review. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 197(5), 350–356. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.109.074526

- Bourdon, K. H., Rae, D. S., Locke, B. Z., Narrow, W. E., & Regier, D. A. (1992). Estimating the prevalence of mental disorders in US adults from the epidemiologic catchment area survey. Public Health Reports, 107(6), 663. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4597243

- Bureau of Labor Statistics (2019, March). Occupational employment and wages, May 2018: 19-3031 clinical, counseling, and school psychologists. https://www.bls.gov/oes/2018/may/oes193031.htm

- Canadian Institute for Health Information. (2019). Health system resources for mental health and addictions care in Canada, July 2019. https://www.cihi.ca/sites/default/files/document/mental-health-chartbook-report-2019-en-web.pdf

- Colling, C., Evans, L., Broadbent, M., Chandran, D., Craig, T. J., Kolliakou, A., Stewart, R., & Garety, P. A. (2017). Identification of the delivery of cognitive behavioural therapy for psychosis (CBTp) using a cross-sectional sample from electronic health records and open-text information in a large UK-based mental health case register. British Medical Journal Open Access, 7(e015297). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015297

- Damschroder, L. J., Aron, D. C., Keith, R. E., Kirsh, S. R., Alexander, J. A., & Lowery, J. C. (2009). Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science, 4(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-4-50

- Dark, F., Whiteford, H., Ashkanasy, N. M., Harvey, C., Crompton, D., & Newman, E. (2015). Implementing cognitive therapies into routine psychosis care: Organisational foundations. BMC Health Services Research, 15(1), 310. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-015-0953-6

- Gould, R. A., Mueser, K., & Bolton, E. (2001). Cognitive behaviour therapy for schizophrenia: An effect size analysis. Schizophrenia Research, 48(2–3), 335–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0920-9964(00)00145-6

- Haddock, G., Eisner, E., Boone, C., Davies, G., Coogan, C., & Barrowclough, C. (2014). An investigation of the implementation of NICE-recommended CBT interventions for people with schizophrenia. Journal of Mental Health, 23(4), 162–165. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638237.2013.869571

- Hafner, H., & Heiden, W. (1997). Epidemiology of schizophrenia. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 42(2), 139–151. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674379704200204

- Harris, P. A., Taylor, R., Minor, B. L., Elliott, V., Fernandez, M., O’Neal, L., McLeod, L., Delacqua, G., Delacqua, F., Kirby, J., & Duda, S. N., & REDCap Consortium. (2019). The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 95(2), 103208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208

- Harris, P. A., Taylor, R., Thielke, R., Payne, J., Gonzalez, N., & Conde, J. G. (2009). Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 42(2), 377–381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010

- Health Quality Ontario. (2016). Schizophrenia: Care for adults in hospitals. http://www.hqontario.ca/portals/0/documents/evidence/quality-standards/qs-schizophrenia-clinical-guide-1609-en.pdf

- Hyde, P. S. (2013). Report to Congress on the nation’s substance abuse and mental health workforce issues. US Dept. for Health and Human Serv., Substance Abuse and Mental Health Serv. (Jan. 2013), 10. http://www.cimh.org/sites/main/files/file-attachments/samhsa_bhwork_0.pdf

- Kessler, R. C., Birnbaum, H., Demler, O., Falloon, I. R., Gagnon, E., Guyer, M., Howes, M. J., Kendler, K. S., Shi, L., Walters, E., & Wu, E. Q. (2005). The prevalence and correlates of nonaffective psychosis in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). Biological Psychiatry, 58(8), 668–676. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.04.034

- Kimhy, D., Tarrier, N., Essock, S., Malaspina, D., Cabannis, D., & Beck, A. T. (2013). Cognitive behavioral therapy for psychosis–training practices and dissemination in the United States. Psychosis, 5(3), 296–305. https://doi.org/10.1080/17522439.2012.704932

- Kopelovich, S. L., Basco, M., Stacy, M., & Sivec, H. (2021). Position statement on the routine administration of cognitive behavioral therapy for psychosis as the standard of care for individuals seeking treatment for psychosis. National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors (NASMHPD) Publications. https://www.nasmhpd.org/sites/default/files/CBTp_Position_Statement_NASMHPD.pdf

- Kopelovich, S., Stiles, B., Monroe-DeVita, M., Hardy, K., Hallgren, K., & Turkington, D. 2021. Psychosis REACH: Effects of a brief CBT-informed training for family and caregivers of individuals with psychosis. Psychiatric Services, 72(11). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.202000740

- Kuipers, E., Fowler, D., Garety, P., Chisholm, D., Freeman, D., Dunn, G., Bebbington, P., & Hadley, C. (1998). London-East Anglia randomised controlled trial of cognitive- behavioural therapy for psychosis: III: Follow-up and economic evaluation at 18 months. British Journal of Psychiatry, 173(1), 61–68. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.173.1.61

- McDonagh, M., Dana, T., Selph, S., Devine, E. B., Cantor, A., Bougatsos, C., Blazina, I., Grusing, S., Fu, R., Kopelovich, S., Monroe-DeVita, M., & Haupt, D. (2018). Treatments for schizophrenia in adults: A systematic review. In Comparative Effectiveness Review No. 198. AHRQ Publication No. 17 (18)-EHC031-EF. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. https://doi.org/10.23970/AHRQEPCCER198

- Morgan, V. A., Waterreuse, A., Jablensky, A., Mackinnon, A., McGrath, J., Carr, V., Bush, R., Castle, D., Cohen, M., Harvey, C., Galletly, C., Stain, H. J., Neil, A. L., McGorry, P., Hocking, B., Shah, S., & Saw, S. (2012). People living with psychotic illness in 2010: The second Australian national survey of psychosis. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 46(8), 735–752. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867412449877

- Mueser, K. T., & Noordsy, D. L. (2005). Cognitive behavior therapy for psychosis: A call to action. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 12(1), 68–71. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy.bpi008

- Mueser, K., Granholm, E., Hardy, K., Sudak, D., Sivec, H., Burkholder, P., & Riggs, S. (2015, November 12–15). A call to action 10 years on: Training US community mental health therapists in CBT for psychosis [Panel discussion]. Association of Cognitive and Behavioral Therapies 49th Annual Convention.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2018). Improving health research on small populations: Proceedings of a workshop. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25112

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2015). Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults (NICE Quality Standard No. 80). https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs80

- Norman, R., Lecomte, T., Addington, D., & Anderson, E. (2017). Canadian treatment guidelines on psychosocial treatment of schizophrenia in adults. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 62(9), 617–623. https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743717719894

- Paris, M., & Hoge, M. A. (2010). Burnout in the mental health workforce: A review. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 37(4), 519–528. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11414-009-9202-2

- Pilling, S., Bebbington, P., Kuipers, E., Garety, P., Geddes, J., Orbach, G., & Morgan, C. (2002). Psychological treatments in schizophrenia: I. Meta-analysis of family intervention and cognitive behaviour therapy. Psychological Medicine, 32(5), 763–782. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291702005895

- Royal College of Psychiatrists. (2014). Report of the second round of the National Audit of Schizophrenia (NAS) 2014. Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership. https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/docs/default-source/improving-care/ccqi/national-clinical-audits/ncap-library/national-audit-of-schizophrenia-document-library/nas_round-2-report.pdf?sfvrsn=6356a4b0_4

- Statistics Canada. (2019, September). Canada’s population estimates: Age and sex, July 1, 2019. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/190930/dq190930a-eng.htm

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2021). Routine administration of cognitive behavioral therapy for psychosis as the standard of care for individuals seeking treatment for psychosis: State of the science and implementation considerations for key stakeholders. https://store.samhsa.gov/product/cognitive-behavioral-therapy-for-psychosis/PEP20-03-09-001

- Thompson, S. K., & Frank, O. (2000). Model-based estimation with link-tracing sampling designs. Survey Methodology, 26(1), 87–98. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/pub/12-001-x/2000001/article/5181-eng.pdf?st=y7j5Vfbk

- Turner, D. T., Burger, S., Smit, F., Valmaggia, L. R., & Van Der Gaag, M. (2020). What constitutes sufficient evidence for case formulation–driven CBT for psychosis? Cumulative meta-analysis of the effect on hallucinations and delusions. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 46(5), 1072–1085. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbaa045

- United States Census Bureau. (2019, February). Census Bureau Projects U.S. and World Populations on New Year’s Day. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2019/new-years-population.html

- Vanasse, A., Courteau, J., Fleury, M. J., Grégoire, J. P., Lesage, A., & Moisan, J. (2012). Treatment prevalence and incidence of schizophrenia in Quebec using a population health services perspective: Different algorithms, different estimates. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 47(4), 533–543. h ttps://d oi.org/1 0.1007%2Fs00127-011-0371-y

- Wood, L., Burke, E., & Morrison, A. (2015). Individual cognitive behavioural therapy for psychosis (CBTp): A systematic review of qualitative literature. Behavioral and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 43(3), 285–297. h ttps:/d oi:1 0.1017/S1352465813000970

- Wykes, T., Steel, C., Everitt, B., & Tarrier, N. (2008). Cognitive behavior therapy for schizophrenia: Effect sizes, clinical models, and methodological rigor. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 34(3), 523–537. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbm114

- Zimmermann, G., Favrod, J., Trieu, V., & Pomini, V. (2005). The effect of cognitive behavioral treatment on the positive symptoms of schizophrenia spectrum disorders: A meta- analysis. Schizophrenia Research, 77(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2005.02.018.