ABSTRACT

Background

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy for voice hearing (CBTv) has been shown to be effective at reducing distress. However, it is unclear why voice hearers might deteriorate or continue to benefit post-intervention. This study aimed to explore therapeutic change processes following CBTv.

Methods

A critical realist, grounded theory methodology was utilised. Individual interviews were conducted with 12 participants who had experienced distressing voice hearing and had completed a CBTv intervention in the last 3–12 months. Participants were recruited from a specialist hearing voices service.

Results

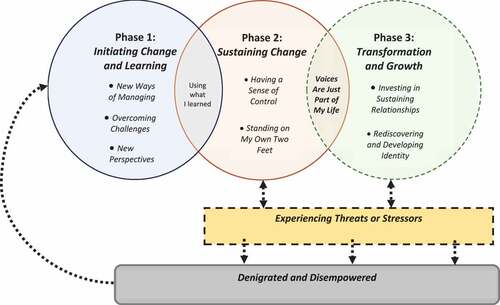

Three categories were found to be facilitative of positive change within CBTv: “New Ways of Managing”, “Overcoming Challenges” and “Gaining New Perspectives”. Five categories denoted the maintenance or furthering of positive change following intervention: “Having a Sense of Control”, “Standing on My Own Two Feet”, “Voices Are Just Part of My Life”, “Investing in Sustaining Relationships”, and “Rediscovering and Developing Identity”. Challenging circumstances faced by participants are also incorporated into a model for maintaining change following CBTv.

Discussion

The model adds to current literature on change processes occurring within and after CBTv. The results support the need for those working with voice hearers post-therapy to focus on rebuilding social relationships, meaning making and identity.

Introduction

Traditionally, help-seeking voice hearers have been offered psychological support in the form of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy for psychosis (CBTp) based on models of positive symptoms. CBT for distressing voices (CBTv) is a symptom-specific form of CBT which involves enhancing coping (Tarrier et al., Citation1990), reducing unhelpful beliefs and bolstering personal resources (Hazell et al., Citation2018). Negative beliefs about the voices and one’s self are thought to maintain distress and are targeted in CBTv (Chadwick & Birchwood, Citation1994; Chadwick et al., Citation1996). Early research suggests that CBTv may be more effective than CBTp (Lincoln & Peters, Citation2019) for those distressed by voice hearing.

CBTv is not limited to psychosis populations and can be used for people who are distressed by voices associated with a range of presenting issues, including personality disorder (Hepworth et al., Citation2013) and experiences of trauma (Steel, Citation2016). It has also generated encouraging outcomes trans-diagnostically (Hazell et al., Citation2018). Approximately half of those that receive CBTv show benefits, with a quarter experiencing large improvements (Paulik et al., Citation2019). Those with increased rates of negative affect and negative symptoms are less likely to benefit (Paulik et al., Citation2018; Thomas et al., Citation2011). Negative beliefs about the self, perceived omnipotence of voices and high voice-related distress have also been associated with poorer CBTv outcomes (Hazell et al., Citation2018; Paulik et al., Citation2018; Thomas et al., Citation2011). Research has suggested a focus on positive self-schema building interventions could be a vehicle to elicit enduring therapeutic change (Birchwood et al., Citation2000).

Outcomes such as reductions in voice-related distress following CBTv have largely been sustained at follow up (Trower et al., Citation2004), however some go on to improve further after treatment whereas others show a deterioration (Wiersma et al., Citation2001). The cognitive models posit cognitive appraisals of voices, the self and social rank are predictive of distress and are targets for change within therapy (Morrison et al., Citation1995). However, self-esteem and beliefs about voices have not consistently been shown to mediate reductions in voice related distress (Paulik et al., Citation2019). Paulik & colleagues suggest further research is needed to understand factors that may be underlying change processes as it is currently unclear how the psychological process of change occurs and is sustained after therapy for distressing voices.

Research aims

It is vital that targeted interventions like CBTv provide the maximum possible benefit. In examining the process by which changes are sustained, or improved upon, we can elucidate factors that support positive change and build this into treatment pathways following CBTv, potentially leading to improved outcomes at follow-up and more durable therapeutic change.

The current study utilised a qualitative grounded theory methodology to understand how changes are experienced and maintained during and after CBTv. Secondary aims investigated what was helpful or hindering in the process of maintaining change.

Methods

Design

A modified grounded theory was deemed appropriate due to the lack of existing theory on CBTv change processes. A critical realist epistemology was adopted which acknowledges that participant responses may be imperfect representations but do however still give valuable insights into the individual’s reality, whilst also providing information on the “real world” (Bhaskar, Citation2013). A social constructivist grounded theory approach was considered; however, the approach situates all knowledge within social parameters and places less emphasis on the physical contexts change may occur in. Equally, other qualitative methodologies were explored and deemed less appropriate due to the research aims of examining the context, structures, and processes of therapeutic change, which critical realist grounded theory is well equipped to study (Bhaskar, Citation2013).

Context

Recruitment occurred through a transdiagnostic service offering CBTv interventions within the UK’s National Health Service (NHS). Clients were typically offered 6–16 individual sessions of manualised CBTv. Sessions were delivered by a range of therapists (e.g. Clinical Psychologists, Assistant Psychologists). Therapists had received training and regular supervision by a Clinical Psychologist, and the service worked alongside clients’ existing mental health teams as an “add-on” to usual treatment. While clients report high levels of adverse life experiences, this service does not offer specific trauma-focused interventions but adopts a trauma informed care approach. Individual adaptations can include the pace, number of sessions, a focus on engagement, breaking down activity into more manageable chunks, fostering a therapeutic interaction during disclosure and flagging key information to the care team. Equally, interventions do not usually focus on concurrent mood difficulties as the referring mental health team would support individuals with this. Clients are encouraged to practice and master ways of coping with distressing voices which can generalise to other areas of difficulty.

Interview design

A semi-structured interview schedule was developed by the authors and involved consultation with a service-user research advisory group. The schedule was largely based upon the Client Change Interview (CCI; Elliott & Rodgers, Citation2008) and was designed to draw out in-depth experiences of change. The CCI attempts to qualitatively capture the processes behind changes occurring from psychological interventions by asking what factors were facilitative and hindering of change processes. Telephone interviews were completed and lasted between 42–76 minutes. Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed. The interview schedules were adapted over time to aid theory development.

Participants

National Health Service ethics and Health Research Authority approval was granted for this study (REC reference: 20/LO/0306). Consent was received via an informed consent form. This document was developed in consultation with a service-user research advisory group to ensure clarity. Details of the study were discussed with potential participants, with the opportunity to ask questions.

Eligibility criteria required participants to have completed ≥6 sessions of CBTv in the previous 3–12 months and to not be experiencing acute distress. Twenty-six participants were referred, eligible and contacted during the recruitment period and twelve agreed to take part. Reasons for non-participation included time, difficulties finding a private space for a phone interview and not wanting to share experiences. No participants were excluded due to levels of distress. Participants were recruited until theoretical sufficiency was deemed to be reached and no new major categories were produced by interviews (Dey, Citation1999). displays participant demographic data.

Table 1. Summary of participant demographics.

Data analysis

The first author conducted analyses following an iterative process, moving between coding, data conceptualisation and theory building (Corbin & Strauss, Citation2008). Line-by-line coding was used to encourage analysis driven by data (Saldaña, Citation2009). Focused coding captured and synthesised initial codes, facilitated by memo writing and diagramming, and eventually contributed to concepts via theoretical sorting (Lempert, Citation2007). Constant comparisons were used throughout analysis to distinguish and group emerging codes, concepts and categories (Glaser & Strauss, Citation1967). Finally, categories were sorted into an explanatory model of change following CBTv.

Quality assurance

The first author conducted all interviews. A bracketing interview and reflexive positive statement sought to highlight potential bias (Tufford & Newman, Citation2012). A research diary recorded the author’s responses in relation to the research and promoted an awareness of the influence on analysis (Yardley, Citation2000). Memo writing occurred throughout analysis to capture reflections, thoughts on how concepts were connected and questions that were provoked by this, building analysis toward theoretical concepts. Coding was cross-checked between authors. Regular supervision discussions of the analytic process and reflections on the first author’s responses to the data took place.

Results

Three non-linear, phases were hypothesised to reflect the study data, covering “Initiating Change and Learning”, “Sustaining Change”, and “Transformation and Growth”, and the processes described in each were not necessarily discrete (). Eight categories denoted the experiences participants described which facilitated the process of initiating, sustaining or building upon positive change.

Figure 1. A theoretical model of change built from participants’ perceptions of CBTv and the time following.

Participants described occasionally occupying a “Denigrated and Disempowered” place. This was characterised by increased distress and was most common before accessing CBTv. Within the model, acute challenges and more enduring difficulties at each phase are referred to as “Experiencing Threats or Stressors”. Encountering these challenges was not necessarily a loss of change, indeed, where participants were well supported the change process was strengthened.

Denigrated and disempowered

Participants feeling denigrated and disempowered could occur at each phase of the change process, and all participants described experiencing this before accessing CBTv. This was often extremely challenging and distressing for participants and described both their interactions with voices and wider life experiences. Difficulties managing were common, with participants very often feeling like they had limited effective coping strategies. Voices were perceived as punishing, powerful and having control over participants.

They [voices] were persecuting me and just like, all day long um, having people run me down in the ground and you know threatening to kill me and stuff like that. [P8]

These challenges were reflected in five participants’ accounts, who expressed disempowered views of themselves and a negative view of one’s own identity.

Experiencing threats and stressors

Threats to wellbeing were acute, challenging and often intense crises that 11 individuals reported whilst attempting to maintain earlier therapeutic change. These crises varied across participants but could centre around therapy ending, feeling alone with voices, problems with physical health, housing insecurity and voices getting worse again with no apparent trigger.

They used to tell me a lot afterwards that I’ve been abandoned and, and that I was left alone like I always had [P4]

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic was also clear in the narratives, with 10 participants sharing feelings of increased isolation, receiving less support from loved ones and services, experiencing worry around the contagious nature of the virus and voices being exacerbated by these additional pressures. If sufficient resources were available to manage “Threats”, for example, through professional support or drawing on personal strengths, the sense of control and empowerment was reinforced.

I think knowing that I could go back to the [service] if I need to stopped me from freaking out [P10]

If interpersonal relationships were unsupportive and professional help limited, as discussed by nine participants, this was experienced as a stressor. “Stressors” related to enduring and more long-term challenges faced by participants which had the potential to be resolved but if not, individuals could end up in a “Denigrated and Disempowered” place similar to before therapy.

Um, they [mental health service] stopped me from approaching them directly asking for help, no, I just suffer, I won’t ask them for help [P2]

Other stressors included the voice-voice hearer relationship being viewed as a battle or a struggle and being treated differently by others.

Phase 1: initiating change and learning

While the suggested model is non-linear, the majority of the “Initiating Change and Learning” phase was described in relation to participants’ experiences of CBTv. As indicated in however, occasionally participants returned to this phase after experiencing overwhelming difficulties following CBTv.

Learning new ways of managing

11 participants described experimenting with novel coping strategies within CBTv, including using distraction, relaxation techniques and ways of interacting with voices.

Yeah because I didn’t know of another way of dealing with how I react to the voices. I had various ways but I never heard of the way the therapist was telling me about. [P2]

Further ways of managing included being able to challenge the voices, which had the potential to reduce participants’ fear and enhance their perceived control over the voices. This was associated with improvements in functioning and distress levels.

Overcoming challenges

“Overcoming Challenges” relates to participants’ experiences of the difficulties that came with initiating change. This could be the taxing nature of therapy, voices being upset by sharing or talking with the therapist being a reminder of past struggles or trauma.

I think the worst like when they just attack you all the time during therapy. Like “you should tell them to F-off”, “she’s talking shit” and stuff like that [P7]

Talking about the voices was a challenge described by four participants, who referred to this as a new experience; something they had not had the opportunity to do before or had been fearful of doing. Whilst this seemed to be particularly difficult and could take an emotional toll on individuals, it was associated with a shift to being more open about voices.

Gaining new perspectives

Gaining new understandings about the voices and oneself was an integral part of the therapy for eight participants. Being able to make sense of current difficulties and having information about voice hearing seemed to lessen participants’ anxiety and distress surrounding voices.

Because like the things the voice say, like sometimes they say they’re going to get you, which is, the work I did with [therapist], because that’s a reflection of what my brother used to say to me, about men in white coats in a white van, taking me away and putting me in a padded cell because I kept talking to someone who wasn’t there. [P10]

Additionally, six participants shared new perspectives on how they viewed themselves. Initial changes related to building confidence in one’s own ability, focusing on self-esteem and centring participants’ thoughts over that of the voices.

It was the talking as much as anything and trying, him trying to get me to think in a different way, not the way that the voices wanted me to think, but to have my own thoughts and opinions. [P12]

Changes in thinking could either occur during CBTv sessions or in the time between appointments. Self-reflection, re-evaluating their experience of voice hearing and what voices said to them, and hearing insights about voice hearing from the therapist were all enablers for participants to gain new perspectives. One participant described how the content of CBTv sessions was not relevant for their difficulties but prompted her to further examine personal ideas of how to meet her needs and manage voices.

It did make me think about things, but the advice I felt like the therapy was giving me um, didn’t match with what I think works for me, um, but it did make me realise what I thought worked for me. [P8]

Phase 2: sustaining change

Having a sense of control

When moving between initiating change and sustaining change, nine participants described using therapy knowledge or finding therapeutic spaces as a transition process. The continuation of specific skills practiced in CBTv, self-help material, and actively creating personally therapeutic spaces at home were all examples of how participants achieved this, represented as the subcategory “Using What I Learned”.

I suppose I don’t want all the therapy that I did have to be waste, so that’s why I’m pushing to incorporate what I’ve learned every day when I’m hearing the voices [P10]

All participants described increased perceptions of control with voices and in their lives more generally.

The voices were angry at me but I could kinda handle them better. I was obeying them more before, I’m not obeying them as much now after therapy. [P7]

This continued sense of control afforded participants agency in their interaction with voices and helped sustain therapeutic change. Nine participants spoke of making choices in how they responded to voices in a way that was not available to them beforehand, such as challenging voices. Within this category, participants’ responses generally reflected them holding a more active role in managing their voices.

I still react like that today, I hear voices every day, I still react like that. I still don’t shout back at them or threaten them or anything like … I don’t self harm so much. [P2]

Nine participants shared specific ways they might use their enhanced control over voices, for example, through using distractions to tune out from voices or attempts at blocking out voices all together. This served to regulate the participants’ closeness to voices and could provide them with a sense of respite.

Standing on my own two feet

Feeling stronger and being more able to draw on personal strengths such as determination was described by 11 participants. This was both within themselves and in their interactions with voices.

… being able to, uh, basically stand on my own two feet because I would have never of got to this place if I couldn’t of done it. [P6]

Although participants described feeling stronger generally, it was apparent that this was not always the case and could vary day-to-day. Alongside feeling empowered, 5 participants spoke of noticing or actively working toward self-esteem improvements.

I find that building, trying to build confidence and trying and talk to people would be a good thing. Yeah, so I’ve been trying to get out a bit more. [P11]

Participants commonly shared how they had begun to feel empowered in relation to voices through changes in beliefs.

I think I was just braver because I’m stronger than him, I wasn’t that weak person that closed down. [P6]

This sense of empowerment seemed to allow seven participants to be able to accept themselves and their physical and psychological needs more readily.

Phase 3: transformation and growth

This final phase related to how previous changes evolved and were built upon in a personally significant way, or new changes emerged. 11 participants contributed to the final categories within this phase to varying degrees, which appeared contingent on the relationship with voices.

Voices are just part of my life

11 participants described fundamental shifts in their relationship with their voices. This was enabled by, and further facilitative of, participants’ sense of control and empowerment described earlier. Participants shared a different attitude being adopted with voices, one that was accepting of their existence and what they said.

I’ve learnt how to deal with them, like it’s just part of my life so I need to deal with them. [P7]

Alongside this acceptance, four participants were able to be more open about the voices to others and found benefits in doing so. For one of the participants, this was supported by her engagement with a Hearing Voices Network (HVN) group.

I can talk about them. I don’t need to block them out. I can almost live with them [P10]

Responses generally reflected the relationship between voice hearer and voices improving, becoming more harmonious and living a fuller life as a result. This was associated with being less distressed and fearful of voices, having respite from voices and being more able to function generally.

I’m able to interact with the voices and what they say may be harsh but I’m able to kind of process it and take it in and find the positives in what they say and find the positives in what they mean [P4]

Investing in sustaining relationships

Voices being accepted and integrated allowed for further changes to occur for some participants. Individuals directed more energy towards important relationships in their lives, and subsequently experienced benefits from this. 10 participants shared how they had become more sociable and gained confidence in communicating with others, which provided motivation for further changes to take place.

… being able to be there for the people I care about really, probably the other major thing, just being able to be there for other people … because they, they inspire you to push further. [P4]

Investments gave individuals the opportunity to identify with others with shared difficulties, receive practical and emotional support, have people around them and to feel more present in the world.

I ring up one of my friends, … it just takes your mind off of what’s been going on in your head, you know it’s just nice to be able to talk about other things [P1]

Rediscovering and developing identity

Enabled by an investment in sustaining relationships, this category pertained to participants building their identity and changing how they viewed themselves.

I s’pose I don’t really recognise myself and I’ve had that for ages and I’m sort of learning more about myself now [P8]

For five participants, identity developed in the context of changing relationships.

… they trust my ability and trust that I’m making myself a better person and, seeing that was probably the biggest thing for me [P4]

Rather than relationships with others, two participants shared how they invested in building a positive relationship with themselves, which involved spending less time with others, and was seen as beneficial. Further changes were achieved through engaging in meaningful activity that was either personally significant or had a therapeutic function for participants. Taking on certain roles through employment or volunteering had provided direction, further shaping identity for four participants.

I really found working to be good for me, a lot of it is to do with self-esteem. There’s a feeling of a victim and everything happening to you, and then there’s getting out there and doing something positive. And my work does make me feel like I’m doing something good [P8]

Eight participants described being a more hopeful person, adopting a positive outlook and having a sense of moving forward. Finding and strengthening an individual identity separate to someone with mental health difficulties or a “voice-hearer” was important to four participants. Participants’ equated this to their behaviour, abilities and outward expression being more congruent with their internal view of themselves, as if returning to who they are with voices being a smaller part of their lives.

Makes me feel like I haven’t got a mental health problem, I can just get on with my life. I can get on with myself more. [P3]

Discussion

The current study sought to understand how voice hearers perceived therapeutic changes to have occurred and have been maintained after accessing a targeted CBT intervention for distressing voice hearing. The resulting model captures eight facilitative categories, conceptualised within three overarching phases, which are thought to contribute to the maintenance of therapeutic changes following CBTv. Various contextual experiences were also included which could provide specific challenges or support the maintenance of change.

Results indicate participants valued the opportunity to develop adaptive coping strategies, ways of responding differently to the voices and new ways of thinking. Similarly, previous research has found changes in perspectives of clients to be a core process in psychological therapy for psychosis (Dilks et al., Citation2008). It has been suggested from voice hearing research and cognitive theory that this process of meaning making can alleviate distress (Morrison, Citation2001; Romme & Escher, Citation1989).

CBTv provided opportunities for participants to develop positive self-efficacy beliefs and effective coping, as previously reported (Macdonald et al., Citation1998). Improvements in self-efficacy during CBTv were associated with a sense of control and empowerment afterwards. However self-efficacy was not specifically described by participants as a central facilitating process. Instead, the importance of connection and rapport building when initiating change was emphasised, in accordance with the wealth of literature on the need for a strong therapeutic alliance in psychological therapies (Bentall et al., Citation2003). Participants commonly reported learning from therapists, perhaps through a process of scaffolding (Bruner, Citation1986). If this were a social process, it is understandable that participants struggled to maintain changes in the context of social isolation or a lack of support, which has been reported in a previous review on psychosis Recovery (Wood & Alsawy, Citation2018). The pandemic clearly contributed to social isolation, potentially resulting in greater importance placed on this context by participants.

Findings in this study were reflective of cognitive models of voice hearing and distress (Chadwick & Birchwood, Citation1994). Potential researcher bias may have influenced data analysis, given all authors are familiar with cognitive theory. Alternatively, CBTv may have provided participants with a framework by which to share their experiences. Sense making has been indicated as particularly relevant in psychological therapy for voice hearing (Longden & Corstens, Citation2019).

Results seem to depart from existing cognitive theory during the final phase of the model. Within this phase, categories conceptualise experiences of integration with voices, developing relationships and living a meaningful life. Whilst this study did not intend to investigate Recovery experiences more generally, these categories are akin to those present in both the voice hearing and general Recovery literature (Romme & Morris, Citation2013; Soundy et al., Citation2015). For example, the categories discussed in phase three of the model are similar to those in the CHIME personal Recovery model (Leamy et al., Citation2011). While Recovery styles have been investigated in voice hearing (De Jager et al., Citation2016), examining the utility of the CHIME model for those with distressing voices may help to clarify these experiences and ways to facilitate them.

Disempowering experiences were described which could disrupt therapeutic change. Negative affect and life stressors have been associated with increases in distressing voices (Chadwick et al., Citation2007; Romme & Escher, Citation2010). This was present in some participants’ accounts whereby overwhelming experiences could result in increased distress which impacted on change maintenance. Research on Recovery in psychosis has discerned the disruptive effects of stigma on processes of positive change (Wood & Alsawy, Citation2018). Within this study, being treated differently by others seemed to act as a long-term or contextual stressor for participants and was a potential obstacle in maintaining changes.

Limitations

Due to the specialist nature of CBTv interventions, recruitment within this study was limited to a small pool of participants. As all participants were recruited from one service and mostly identified as White British, this could have introduced bias into the research. Black, Asian and people from minority ethnic backgrounds are overrepresented in the prevalence of psychosis diagnoses, however, were not represented in this study (Fernando, Citation2017). Young voice hearers and those with a shorter duration of voices were also underrepresented.

The current study worked toward theoretical sufficiency of categories, as opposed to saturation, meaning there are potentially further codes to be explored within the research questions. Further research would be needed to test hypotheses within the model.

Implications

Many participants within this study perceived CBTv as helpful. Efforts should be made to increase access to CBTv, which would require further training of therapists and services being supported to identify clients. The findings highlight the need for clinical services to strengthen the associations between therapy and the processes which maintain changes. One way this may be achieved is by building conversations of change and learning into clinical interventions, much like relapse prevention plans used in CBTp and psychosis services (Birchwood et al., Citation1989), to support clients to consider how potential challenges can be managed and therapeutic changes maintained. An explicit focus on goal setting at the end of therapy and/ or offering top up “booster sessions” could encourage processes in phases two and three of this model.

Participants described how changes were difficult to maintain in the face of overwhelming challenges. Voice hearing has been known to be a potentially long-term experience which can continue to cause distress (Harrow et al., Citation2014). Psychological therapies endeavouring to signpost clients who hear voices to places of ongoing support when needed, such as their GP or HVN groups, may be more likely to facilitate enduring changes. Similarly, providing people who hear voices with resources, such as self-help, or potentially access to support groups following CBTv could work to mitigate some of the challenges participants faced. In this way, those who have accessed CBTv may feel best supported, with changes being more readily sustained and built upon. Anti-stigma campaigns through social media, within schools and utilising psychosocial frameworks may also reduce the burden of stigma on voice hearers (Longden & Read, Citation2017; Pinfold et al., Citation2003; Sampogna et al., Citation2017).

Theoretical explanations relating to enduring change should consider an emphasis on meaning, social relationships, identity and integration with people distressed by voices specifically. Long-term research combining outcomes and qualitative methods to triangulate results on the durability of changes from psychological interventions with people who hear distressing voices may further highlight specific factors and their influence over time.

Conclusion

In examining participant accounts during and after CBTv, this study found therapeutic change to be enduring when experiences following interventions facilitated positive appraisals about the self and greater control with voices. The current model describes an ongoing process whereby participants accessing CBTv could move from disempowerment toward increased agency by using learnings from therapy and with support from others. Challenges arose for participants within this study. However, with adequate support and positive self-efficacy beliefs, these could often be overcome and then reinforced the maintenance of change. The final phase of the model suggests voices becoming more integrated, focusing on positive relationships and exploring identity to support enduring change. In contrast, fighting with voices and experiencing stigma were barriers that could disrupt the maintenance of changes. This model adds to current literature on people who hear distressing voices and reinforces the need to examine the processes that can facilitate and inhibit change following psychological interventions.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express thanks to the participants of this study. Also, colleagues in the Research and Development department who supported the study, in particular the Lived Experience Advisory Panel who consulted on the research and Hazel Frost and Sophie Green (Research Assistants) for their help with recruitment. A final thanks to fellow trainees for offering advice and support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bentall, R., Lewis, S., Tarrier, N., Haddock, G., Drake, R., & Day, J. (2003). Relationships matter: The impact of the therapeutic alliance on outcome in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research, 60(1), 319. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0920-9964(03)80274-8

- Bhaskar, R. (2013). A realist theory of science. Routledge.

- Birchwood, M., Meaden, A., Trower, P., Gilbert, P., & Plaistow, J. (2000). The power and omnipotence of voices: Subordination and entrapment by voices and significant others. Psychological Medicine, 30(2), 337–344. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291799001828

- Birchwood, M., Smith, J., Macmillan, F., Hogg, B., Prasad, R., Harvey, C., & Bering, S. (1989). Predicting relapse in schizophrenia: The development and implementation of an early signs monitoring system using patients and families as observers, a preliminary investigation. Psychological Medicine, 19(3), 649–656. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291700024247

- Bruner, J. (1986). Actual minds, possible worlds. Harvard University Press.

- Chadwick, P., Barnbrook, E., & Newman-Taylor, K. (2007). Responding mindfully to distressing voices: Links with meaning, affect and relationship with voice. Journal of the Norwegian Psychological Association, 44(5), 581–587. https://psykologtidsskriftet.no/node/14175/pdf

- Chadwick, P., & Birchwood, M. (1994). The omnipotence of voices a cognitive approach to auditory hallucinations. British Journal of Psychiatry, 164(2), 190–201. http://dx.doi.org/10.1192/bjp.164.2.190

- Chadwick, P., Birchwood, M., & Trower, P. (1996). Cognitive therapy for delusions, voices and paranoia. John Wiley & Sons.

- Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2008). Basics of qualitative research (3rd ed.): Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452230153

- De Jager, A., Rhodes, P., Beavan, V., Holmes, D., McCabe, K., Thomas, N., McCarthy-Jones, S., Lampshire, D., & Hayward, M. (2016). Investigating the lived experience of recovery in people who hear voices. Qualitative Health Research, 26(10), 1409–1423. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732315581602

- Dey, I. (1999). Grounding grounded theory: Guidelines for qualitative inquiry. Academic Press.

- Dilks, S., Tasker, F., & Wren, B. (2008). Building bridges to observational perspectives: A grounded theory of therapy processes in psychosis. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 81(2), 209–229. https://doi.org/10.1348/147608308X288780

- Elliott, R., & Rodgers, B. (2008). Client change interview schedule: Follow up version (v5). http://www.drbrianrodgers.com/research/client-change-interview

- Fernando, S. (2017). Institutional racism in psychiatry and clinical psychology: Race matters in mental health. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-62728-1

- Glaser, B., & Strauss, A. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Sociology Press.

- Harrow, M., Jobe, T. H., & Faull, R. N. (2014). Does treatment of schizophrenia with antipsychotic medications eliminate or reduce psychosis? A 20-year multifollow-up study. Psychological Medicine, 22(14), 3007–3016. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291714000610

- Hazell, C. M., Hayward, M., Cavanagh, K., Jones, A. M., & Strauss, C. (2018). Guided self-help cognitive-behaviour Intervention for VoicEs (GiVE): Results from a pilot randomised controlled trial in a transdiagnostic sample. Schizophrenia Research, 195, 441–447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2017.10.004

- Hepworth, C. R., Ashcroft, K., & Kingdon, D. (2013). Auditory hallucinations: A comparison of beliefs about voices in individuals with schizophrenia and borderline personality disorder. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 20(3), 239–245. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.791

- Leamy, M., Bird, V., Le Boutillier, C., Williams, J., & Slade, M. (2011). Conceptual framework for personal recovery in mental health: Systematic review and narrative synthesis. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 199(6), 445–452. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.110.083733

- Lempert, L. B. (2007). Asking questions of the data: Memo writing in the grounded theory tradition. In A. Bryant & K. Charmaz (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of grounded theory (pp. 245–264). SAGE Publications.

- Lincoln, T. M., & Peters, E. (2019). A systematic review and discussion of symptom specific cognitive behavioural approaches to delusions and hallucinations. Schizophrenia Research, 203, 66–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2017.12.014

- Longden, E., & Corstens, D. (2019). Making sense of voices: Perspectives from the hearing voices movement. In K. Berry, S. Bucci, & A. N. Danquah (Eds.), Attachment theory and psychosis: Current perspectives and future directions (pp. 131–145). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315665573

- Longden, E., & Read, J. (2017). ‘People with problems, not patients with illnesses’: Using psychosocial frameworks to reduce the stigma of psychosis. The Israel Journal of Psychiatry and Related Sciences, 54(1), 24–28. https://cdn.doctorsonly.co.il/2017/08/05_People-with-problems.pdf

- Macdonald, E. M., Pica, S., McDonald, S., Hayes, R. L., & Baglioni, A. J., Jr. (1998). Stress and coping in early psychosis: Role of symptoms, self-efficacy, and social support in coping with stress. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 172(33), 122–127. https://doi.org/10.1192/S0007125000297778

- Morrison, A. (2001). The interpretation of intrusions in psychosis: An integrative cognitive approach to hallucinations and delusions. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 29(3), 257–276. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465801003010

- Morrison, A., Haddock, G., & Tarrier, N. (1995). Intrusive thoughts and auditory hallucinations: A cognitive approach. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 23(3), 265–280. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465800015873

- Paulik, G., Hayward, M., Jones, A. M., & Badcock, J. (2019). Evaluating the “C” and “B” in brief CBT for distressing voices in routine clinical practice in an uncontrolled study. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy 26(6), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2395

- Paulik, G., Jones, A. M., & Hayward, M. (2018). Brief coping strategy enhancement for distressing voices: Predictors of engagement and outcome in routine clinical practice. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 25(5), 634–640. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2299

- Pinfold, V., Toulmin, H., Thornicroft, G., Huxley, P., Farmer, P., & Graham, T. (2003). Reducing psychiatric stigma and discrimination: Evaluation of educational interventions in UK secondary schools. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 182(4), 342–346. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.182.4.342

- Romme, M. A., & Escher, S. (1989). Hearing voices. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 15(2), 209–216. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/15.2.209

- Romme, M. A., & Escher, S. (2010). Personal history and hearing voices. In F. Larøi & A. Aleman (Eds.), Hallucinations: A guide to treatment and management (pp. 233–256). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/med/9780199548590.003.0013

- Romme, M. A., & Morris, M. (2013). The recovery process with hearing voices: Accepting as well as exploring their emotional background through a supported process. Psychosis, 5(3), 259–269. https://doi.org/10.1080/17522439.2013.830641

- Saldaña, J. (2009). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Sage Publications Ltd.

- Sampogna, G., Bakolis, I., Evans-Lacko, S., Robinson, E., Thornicroft, G., & Henderson, C. (2017). The impact of social marketing campaigns on reducing mental health stigma: Results from the 2009-2014 time to change programme. European Psychiatry, 40, 116–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2016.08.008

- Soundy, A., Stubbs, B., Roskell, C., Williams, S. E., Fox, A., & Vancampfort, D. (2015). Identifying the facilitators and processes which influence recovery in individuals with schizophrenia: A systematic review and thematic synthesis. Journal of Mental Health, 24(2), 103–110. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638237.2014.998811

- Steel, C. (2016). Psychological interventions for working with trauma and distressing voices: The future is in the past. Frontiers in Psychology, 7(2035), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.02035

- Tarrier, N., Harwood, S., Yusopoff, L., Beckett, R., & Baker, A. (1990). Coping Strategy Enhancement (CSE): A method of treating residual schizophrenic symptoms. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 18(4), 283–293. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0141347300010387

- Thomas, N., Rossell, S., Farhall, J., Shawyer, F., & Castle, D. (2011). Cognitive behavioural therapy for auditory hallucinations: Effectiveness and predictors of outcome in a specialist clinic. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 39(2), 129–138. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465810000548

- Trower P, Birchwood M, Meaden A, Byrne S, Nelson A, & Ross K. (2004). Cognitive therapy for command hallucinations: randomised controlled trial. British Journal of Psychiatry, 184(4), 312–320. 10.1192/bjp.184.4.312

- Tufford, L., & Newman, P. (2012). Bracketing in qualitative research. Qualitative Social Work, 11(1), 80–96. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473325010368316

- Wiersma, D., Jenner, J. A., van de Willige, G., Spakman, M., & Nienhuis, F. J. (2001). Cognitive behaviour therapy with coping training for persistent auditory hallucinations in schizophrenia: A naturalistic follow-up study of the durability of effects. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 103(5), 393–399. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0447.2001.00213.x

- Wood, L., & Alsawy, S. (2018). Recovery in psychosis from a service user perspective: A systematic review and thematic synthesis of current qualitative evidence. Community Mental Health Journal, 54(6), 793–804. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-017-0185-9

- Yardley, L. (2000). Dilemmas in qualitative health research. Psychology & Health, 15(2), 215–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870440008400302