ABSTRACT

Background: Early integration of oncology and patient-centered palliative care is the recommended clinical practice model for patients with advanced cancer. General and specific communication skills are necessary to achieve integrated patient-centered care, but require organized training to be adequately mastered. Challenges and barriers on several levels, i.e. organizational, professional and individual may, however, hamper implementation. The development, implementation, and evaluation of such an educational program focusing on communication skills contain many steps, considerations and lessons learned, which are described in this article.

Methods: A multi-professional faculty developed, implemented, and evaluated an educational program through a 5-step approach. The program was part of a Norwegian cluster-randomized controlled trial aiming to test the effect of early integration of oncology and palliative care for patients with advanced cancer.

Results: The result is the PALLiON educational program; a multi-faceted, evidence-based, and learner-centered program with a specific focus on physicians’ communication skills. Four modules were developed: lectures, discussion groups, skills training, and coaching. These were implemented at the six intervention hospitals using different teaching strategies. Evaluation in a subgroup of participants showed a positive appraisal of the group discussions and skills training.

Conclusion:We present our experiences and reflections regarding implementation and lessons learned, which should be considered in future developments and implementations; (1) Include experienced faculty with various backgrounds, (2) Be both evidence-based and learner-centered, (3) Choose teaching strategies wisely, (4) Expect resistance and skepticism, (5) Team up with management and gatekeepers, (6) Expect time to fly, and (7) Plan thorough assessment of the evaluation and effect.

Trial registration: ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03088202.

Background

Early integration of palliative care into oncology is the recommended clinical practice model for patients with advanced cancer [Citation1,Citation2]. Improved health outcomes are shown for both patients and carers, in addition to cost-effectiveness and reduced use of the health care services [Citation3–5].

Patient-centered care and communication have been recognized as essential in integrated oncology and palliative care to empower the patient and promote care that is respectful of the patient’s needs, preferences, and values [Citation6–9]. These elements should be part of treatment discussions and evaluations in multi-disciplinary team meetings that most often focus on the tumor, not on the patient with cancer. The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) and European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) clinical guidelines both emphasize that patient-centered care and communication should be addressed in routine clinical practice, both in oncology and in palliative care [Citation2,Citation10,Citation11]. However, combining patient-centered care and tumor-centered care focusing on anticancer treatment is not straightforward [Citation12,Citation13]. Challenges and barriers exist on several levels – be it organizational, political, professional, or individual [Citation14,Citation15]. As such, these may be counterproductive for physicians who need to change their practice and patient approach [Citation16].

Integration of oncology and palliative care involves a series of context-specific communication skills such as delivering serious news, shared decision-making, and end-of-life communication. These skills, representing a patient-centered approach, require specific training to be adequately mastered [Citation17–21]. Several communication skills training programs focusing on improving cancer care exist; also some directed at patients with advanced cancer [Citation22–25]. These educational programs are, however, not specifically developed with the intent to promote the integration of oncology and palliative care [Citation26], although a few include discussions about the transition to palliative care [Citation27].

The Norwegian cluster randomized controlled trial (C-RCT); Palliative Care Integrated in Oncology, PALLiON, (ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT03088202) aims to test the effect of integrated, patient-centered oncology and palliative care with time-based referrals to palliative care [Citation28] on the use of chemotherapy at the end of life. In this context, we have developed an educational program to enable physicians to comply with the new practices. This program specifically focus on relevant communication skills and was implemented as one part of the intervention.

In the PALLiON project, a three-parted complex intervention in six hospitals is compared to conventional care in another six hospitals [Citation28]. The intervention consists of the following: a) the educational program for oncologists, residents, and palliative care physicians presented in this article; b) development and implementation of specific patient-centered care pathways with early referral to palliative care; and c) systematic registrations of patient- and caregiver-reported outcomes.

Here, we report on the development and implementation of the educational program, and the small-scale evaluation of this. The intention is to provide developers, researchers, teachers, or attendees of communication skills training programs insight into the steps, considerations, and reflections we had during this complex process and the lessons learned, to the benefit of others in similar situations.

Methods

In 2015, a multi-professional faculty was established consisting of oncologists, psychologists, a palliative care physician, a nurse, and professors and researchers in palliative medicine, behavioral medicine, and clinical communication. Most participants had long-standing experience with developing, teaching, and assessing communication skills training programs for medical students and various medical professions.

The faculty’s directive was to develop and implement an educational program with a focus on competence and skills in communication relevant for the main aim of the PALLiON project: To achieve integration and improve patient-centered care for patients with advanced cancer [Citation28].

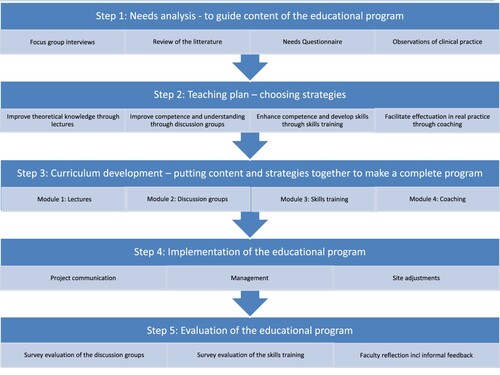

The complex process of developing, implementing, and evaluating the program consisted of five steps () that are described in the next sections followed by our reflections on the lessons learned.

Figure 1. The 5-step approach of developing, implementing and evaluating the PALLiON educational program.

Step 1: needs analysis

In Step 1, the goals were to identify current challenges and educational needs among physicians caring for patients with advanced cancer and to draw implications for the program development.

Step 1 was conducted with four different methodological approaches:

Focus group interviews

Review of the literature

Needs questionnaire

Observations of clinical practice

Focus group interviews

Focus group interviews with oncology residents, oncologists, oncology and palliative care nurses and physicians were conducted in groups, divided by profession. The aims were to explore the participants’ perceived challenges and learning needs in their care for patients with advanced cancer and to analyze how these perceptions could provide insight into how to improve care in an integrated care model. The results have been presented elsewhere [Citation16]. In summary, the discussions in the interviews concerned three broad themes: (1) emphasis on patients’ best interest, perceived as hindered, (2) by unsatisfactory organizational conditions, and (3) by the clinical practices of colleagues. Participating physicians and nurses generally expressed a positive self-view but were more critical towards others and described a tumor-directed treatment focus as prevailing among oncologists. The participants did not report pressing learning needs. However, they did mention some patient situations that they perceived as more challenging than others, such as meeting young patients with children, and disagreements between patients and carers regarding treatment decisions.

Review of the literature

The faculty reviewed the literature on communication in cancer care, educational developments, and theoretical perspectives on the integration of patient-centered palliative care in oncology. Existing curricula and interventions in cancer care focusing on communication skills were reviewed. Particularly relevant literature describing communication skills training programs, consultation models, and applicable concepts both within cancer care and in general were assessed carefully – including the Comskil Model [Citation29], the Oncotalk Model [Citation27], the Four Habits Model [Citation30], SPIKES - a six-step protocol for delivering bad news [Citation31], the Calgary Cambridge Guide [Citation32], the Australian guidelines for prognostic and end-of-life communication [Citation7], and concept papers on shared decision-making [Citation33,Citation34]. In addition, we reviewed previous intervention studies [Citation35,Citation36]. By doing this, we identified essential competence and relevant communication skills to include in the educational program. We also explored whether a need for improved practice was reported in observational or intervention studies. There is a vast literature on the importance and need for the improvement of communication skills of providers of advanced cancer care, and numerous training programs, and intervention studies have been conducted [Citation18,Citation37–39]. The literature review told us that basic skills, such as eliciting the patient perspective and showing empathy, and skills specifically relevant for this patient group such as delivering serious news and providing prognostic information, are essential, yet insufficiently managed [Citation40–43]. These topics were emphasized in many curricula of the communication skills training programs reviewed [Citation27,Citation44].

Several papers highlighted the necessity of competence about anti-cancer treatments to provide good palliative care and vice versa; the need for knowledge and competence about palliative care for oncologists to manage integrated care [Citation45,Citation46]. The mastery of symptom management, knowledge about end-of-life care, and the process of dying are also emphasized [Citation47].

Needs questionnaire with physicians attending communication skills training

A needs questionnaire was completed by all participants at the six intervention sites prior to the communication skills training (n = 159). The survey, modified from Finset and colleagues [Citation25], consisted of 26 items of self-perceived learning needs related to both basic and more specialized communication skills rated on a Likert scale ranging from 1 very low to 5 very high perceived needs.

The participants reported moderate learning needs (mean 3.14). The highest learning needs were reported on specialized skills such as handling patients with small children (mean 3.74), carers who disagree (mean 3.70), and how to provide information about prognosis (mean 3.54). The more basic skills such as listening (mean 2.71) and showing empathy (mean 2.64) were not emphasized.

Observations of clinical practice at the cancer clinic

To observe the current practice, three members of the faculty attended inpatient and outpatient consultations as silent observers. Although not emphasized by the clinicians, faculty members identified a need for the improvement of basic communication skills, such as listening, asking open-ended questions, and eliciting the patient perspective. The discrepancy between self-perceived and observed skills and learning needs has been documented earlier as well [Citation48].

Conclusions and implications from Step 1 for the program development:

Knowledge and competence in anti-cancer treatment, symptom management, end-of-life care, and patient-centered communication are prerequisites for good patient care and should, therefore, be objectives of an educational program.

Focus on improving competence and skills related to the consultation structure and the physician-patient relation throughout the disease trajectory proved to be necessary components of an educational program, despite the low self-perceived need among the physicians. This is supported by the literature review and our observation of current practice.

Both basic patient-centered communication skills and specialized skills with specific relevance for this patient population need to be included.

Step 2: teaching plan – choosing strategies

In Step 2, the goal was to develop a teaching plan. The most successful existing educational programs have been those focusing on the learner’s perspective and include exercises for reflection and practice [Citation20,Citation49,Citation50]. The most used strategy in communication skills training is role-play [Citation51], often in combination with lectures and illustrations of behavior. Previous programs do, however, vary considerably with regard to length and practical implementation [Citation52]. Only a limited number of implemented programs include real-life feedback, but positive experiences have been reported [Citation53]. In summary, the most important factor for the success of educational programs is the use of multiple teaching strategies. Ideally, both didactic and behavioral strategies should be applied.

Based on this principle of a mixed strategy approach, we made a teaching plan encompassing four strategies aiming to:

Improve theoretical knowledge with lectures

Improve competence and understanding using discussion groups directed by a specifically designed e-learning program

Enhance competence and improve communication skills through practical skills training

Facilitate execution of learned communication skills in real practice by one-to-one coaching sessions

Lectures

A set of lectures was planned to inform participants about the PALLiON project and provide the essential theoretical knowledge and competence pinpointed in Step 1. The faculty also planned to present relevant communication challenges related to the topics to put them into context with the overall goal of the educational program.

E-learning program conducted in discussion groups

An e-learning program was planned as an educational resource to be carried out in the discussion groups, that included:

An overview of the communication skills addressed in the program

Illustrative films of clinical practice

Related queries for reflection

Evidence-based texts to answer each query and describe related communication skills

A list of potential phrases related to each communication skill

Relevant literature

Practical skills training

The practical skills training was planned to be conducted in smaller groups, with a focus on role-playing. The intended structure was:

6–8 h training

Short narratives/cases for the role-plays

Practice in trying out specific communication skills, not role-playing entire consultations

Emphasis on finding good phrases to try out together

All physicians were to play both patient and physician throughout the day

Coaching

To provide clinicians with the opportunity to try the skills in clinical practice, the faculty planned to conduct a one-to-one coaching session with each participating physician. The faculty developed and piloted a coaching guide. The guide was then revised based on the feedback received. The coaching should be performed:

After skills training

In any patient-consultation chosen by the clinician

Based on the revised coaching guide

Conclusions and implications from Step 2:

According to the literature, the chance of success with an educational program increases with the use of various teaching strategies.

Therefore, we planned two didactic approaches, consisting of lectures and discussion groups, and two behavioral approaches, with skills training and coaching.

Step 3: curriculum development – putting together content and strategies to make a complete program

In Step 3, the first goal was to decide the overall learning objectives and skills we wanted to teach the physicians based on the findings from Steps 1 and 2. The second goal was to develop the curriculum of the complete educational program.

Overall learning objectives and skills

The faculty decided on six learning objectives and 16 related skills (). The objectives entail the consultation structure; they are overarching and basic and relevant for all consultations and patient groups. The 16 skills are both basic and more particularly relevant for patients with advanced cancer.

Table 1. Learning objectives and skills.

The complete educational program consists of four parts known as modules, intended for sequential implementation. The objectives and skills are addressed in the different modules in various ways.

Module 1

The faculty decided to make eight lectures. The first three were introductory lectures presenting the PALLiON project followed by five lectures on central issues related to the treatment and care of patients with advanced cancer ().

Table 2. Lectures with specified learning objectives and related communication challenges.

Experienced physicians, specialists in oncology and/or palliative medicine gave the lectures. The faculty reviewed all manuscripts beforehand. Learning objectives and potential communicative challenges related to the topics were included in the lectures. The lectures were in a pptx.-format and recorded with a voice-over. The total duration of the eight lectures was 3.5 h.

Module 2

The e-learning program has an overall duration of three hours when conducted in discussion groups, which is the intended educational format. A website containing 18 topics and queries for discussion in the groups was designed. Four films were made for the purpose of illustrating physician-patient communication on the selected topics (). A case with a young female patient, married and with young children, who has been diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer, was developed based on the results of Step 1. Clinicians with extensive experience in clinical oncology acted as physicians with a nurse as the patient, to make the films as realistic as possible.

Table 3. Content of the discussion groups.

The website also contains descriptions of the specific communication skills referred to, references to relevant literature, and examples suggesting exactly what to say.

Module 3

Skills training consists of a one-day course for groups of four to nine physicians. The group training starts with a round of introductions and exploration of the participants’ expectations, perceived challenges, and prior experience with skills training. Specific themes are subject to discussions and role-played in sequences of about 30–45 min (). Nine pre-made communicative challenges, with related assignments and patient cases provide the framework for the role-plays.

Table 4. Content of skills training.

Module 4

The real-life practice known as coaching takes place two to ten weeks after the group skills training. Each participant has a coach sitting in as an observing participant during a patient consultation. Immediately afterwards, the clinician receives feedback following the guide provided in . The choice of consultation is up to the physician.

Table 5. Coaching guide.

Together, these four modules make up the complete educational program.

Step 4: implementation

In Step 4, the goal was to implement the educational program at the six PALLiON intervention hospitals. The program was implemented and completed at all six sites with 159 participants, between 2017 and 2019.

Three elements were especially relevant in the implementation process:

Project communication

Management

Site adjustments

Project communication

Project communication involved the provision of information about the PALLiON project to all stakeholders. The target audience was the local project investigators (PIs) and the management at each site, participating physicians, and study nurses. The project management prioritized thorough and iterative project information as an important part of the implementation process to improve chances of success. In addition, the local PIs and members of the faculty presented the project and its elements to the staff several times.

Project communication also involved information about the ethical and practical conduction of the program, with specific emphasis on confidentiality for all involved.

Management

The project management visited all sites to team up with the local management and provide information and support if necessary. We regard the involvement of the local management as imperative to succeed with the implementation. Designated, motivated, and committed local PIs were heavily involved throughout the process and were responsible for local organization and implementation, supported by the faculty. All local PIs were experienced physicians. They underwent a teach-the-teachers program that was developed and hosted by the faculty who have extensive experience in this. The program included one day of self-study of the e-learning program and the skills training and coaching guides, prior to a one-day teach-the-teacher seminar. This was considered sufficient to provide PIs with the necessary knowledge about the content and implementation of the educational program, based on the faculty’s previous experience. Moreover, this was feasible to organize within the restricted timeframe of the PALLiON project and those involved. The local PIs were accompanied by proficient faculty teachers in skills training supplemented with an open invitation to contact the faculty for further input, discussions, or support of any kind. The seminar program included:

Information about the theoretical and empirical background and content of the educational program.

The role of the local PI, with a focus on practical elements (such as organization of groups, facilities for using online material etc.) and on how to collaborate with the faculty teacher throughout the educational program.

How to implement the four modules. The co-leading of the practical skills training received specific emphasis. We also conducted role-plays to practice the co-leading of groups.

Site adjustments

To optimize the implementation of the different modules within the educational program, some site adjustments were made:

At the largest hospital, the lectures were given in the conventional face-to-face format, while physicians at smaller hospitals watched the audiotaped lectures in groups.

The duration and frequencies of discussion groups varied across hospitals. Some sites conducted one or two longer sessions, while others had shorter and more frequent ones. As an example, one hospital organized 10 sessions of 25 min each, while another conducted two 90 min groups.

The faculty teachers traveled to all intervention sites to conduct the skills training, with local PIs contributing as co-leaders. Some sites had one full day of skills training, while other sites had two shorter days.

The local PI or a teacher from the faculty performed the coaching sessions.

Step 5: evaluation

The goal of Step 5 was to do a small-scale evaluation of the educational program. The program is only one part of the three-parted PALLiON intervention that was conducted at different times at six hospitals across Norway. A rigorous outcome assessment was not planned due to logistical and feasibility issues within the timeframe and the large scope of the PALLiON project. Instead, we chose to do an evaluation among a subgroup of the participants, even if this provided a limited amount of data. Due to the vast difference in the completion time of the program and a high turnover among residents everywhere, we decided to perform the evaluation at the Oslo University Hospital (OUH) only. The evaluation was conducted in three ways:

A survey evaluation of the discussion groups*

A survey evaluation of the skills training*

Faculty reflections

* The different number of participants in the discussion groups and skills training at the OUH is due to non-attendance for various reasons, i.e. turn-over, sick leave, clinical duties etc.

Evaluation of the discussion groups

An evaluation survey was developed and sent to all participants at the OUH after completion of the groups in 2017 (N = 95). Sixty (63%) of the participants replied. Forty-four (73%) rated the discussion groups as good or very good on a five-point scale from very bad to very good. Three skills were highlighted as particularly useful; how to set the agenda, how to introduce palliative care, and how to break bad news.

Evaluation of the skills training

The second evaluation survey was sent to all OUH participants (N = 77) at the skills training, in 2019. Fifty-three (69%) of the participants replied. Two out of three participants reported not having had any expectations prior to the skills training, while five (9%) were negative before training, and 12 (23%) reported high expectations.

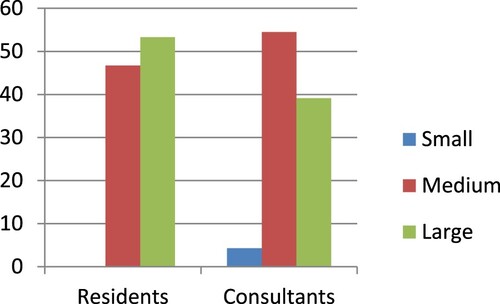

One participant reported only slight or no benefit from training, while 51% (n = 27) reported medium and 47% (n = 25) reported large benefits. Benefits from training among residents and consultants (n = 53) are reported in .

Figure 2. Reported learning benefit in percent for skills training program for residents and consultants (N = 53).

Forty-seven (89%) participants would recommend the skills training to colleagues, whereas six said they might (7%) or were uncertain (4%).

Faculty reflections

During the five years that it took to develop and conduct the educational program, the faculty had weekly meetings to discuss and evaluate progress, implementation strategies, share experiences and feedback. We also had close contact with the local PIs about their experiences and feedback they had received. Some PIs sent written evaluation reports to the faculty. The project management, faculty, and all local PIs met once a year to discuss practices and share experiences.

Discussion and lessons learned

The PALLiON educational program was developed, implemented, and evaluated through a 5-step approach. It is a multi-faceted, needs- and evidence-based program with a specific focus on communication skills to promote integrated, patient-centered oncology and palliative care. The program is based on previous developments and interventions regarding content and strategy and includes a multi-faceted approach as recommended previously [Citation49].

In our program, four modules that were implemented using different teaching strategies at the six intervention hospitals were developed. Lectures, illustrations, and role-plays are commonly used strategies in comparable programs as well. Individually tailored feedback, i.e. coaching, is less common but has been reported as part of communication skills training in cancer care [Citation54]. Coaching as a method of letting participants try out new skills in real-life clinical practice and receiving immediate feedback is a promising approach, but more research on potential benefits is warranted.

While the content was chosen and put together to form a novel program to facilitate the integration of oncology and palliative care, the evidence-based communication skills that were included have proven feasible, efficient, and effective elsewhere, and are therefore, not novel [Citation24,Citation30,Citation36,Citation55,Citation56]. Evaluation in a subgroup of the participants provided us with cautious optimism that the program was well received.

However, we do not know if the program led to sustainable changes in physician behavior. The implementation of new knowledge and skills into clinical practice should be considered an organizational challenge and the complexity of such an intervention should not be under-estimated [Citation57]. Barriers and facilitators need to be acknowledged at multiple levels. Management support, involvement of stakeholders, level of competence, and economic incentives are examples of important facilitators. Another crucial factor is that all involved perceive the change as beneficial. However, a fear of losing autonomy and the inclination to prioritize professional individualism over research findings within the medical profession are important barriers to consider. Furthermore, the unidimensional, tumor-centered focus may make physicians less motivated to prioritize education in patient-centered care, thereby contributing to delayed referrals to palliative care. Time constraints and other organizational factors are also known barriers to implementing change [Citation58]. We considered several of these elements in the development and implementation of the educational program. In retrospect, however, we acknowledge that we should probably have regarded this as an implementation project and included upfront analyses and plans for handling potential barriers and facilitators to succeed in changing the behavior of the health care providers. For similar future projects, we highly recommend following an acknowledged implementation science method to increase the chances of successful implementation.

In the following, we highlight seven lessons learned with possible solutions for consideration in the development and implementation of similar communication skills training programs:

Include faculty members with various backgrounds and with relevant experience

In the development and implementation of a comprehensive educational program, the faculty should consist of professionals with various backgrounds. In a context like this, some should be clinicians while others must possess experience with communication-related programs [Citation10,Citation39].

| (2) | Be both evidence-based and learner-centered | ||||

Creating an evidence-based curriculum is paramount [Citation10,Citation59,Citation60]. Being learner-centered is essential as well. This can be achieved by adding elements suggested by the participants to increase perceived relevance and motivation. This also relates to defining the correct level of difficulty. We experienced, for example, that the most experienced physicians perceived lectures in Module 1 as too basic. Lectures that are tailored to the participants’ skill levels are preferable and probably better received. A possible solution in this program could have been to keep lectures for residents only.

| (3) | Choose teaching strategies wisely | ||||

Teaching strategies should also be evidence-based [Citation10,Citation59,Citation60]. Several other elements should also be considered when choosing teaching strategies. These are our experiences:

Making good lectures with audio recording is time consuming and challenging. Other options, e.g. online lectures, should be considered.

Making illustrative films of physician-patient communication is time consuming and requires professional assistance. However, when films are produced, they may be valuable in other educational settings, as well.

Discussion groups of 25 min are too short. It takes a few minutes to get into a ‘discussion mode’. Time is often compromised as some participants always run a few minutes late and need to leave immediately after the session for clinical work. Some sites conducted fewer but longer sessions with greater success. We also tried to leave it to the groups to facilitate the discussions. In the participant-led groups, the discussions tended to drift off to unrelated topics. Thus, we recommend the use of experienced facilitators to assist the discussion.

Important factors for the successful conduct of skills training are group size, duration, location, and teaching approach. We experienced that the optimal group size was six to eight participants. Furthermore, training is easier to conduct outside of the hospital to avoid the constant paging of clinicians. Regarding the duration of the skills training, we tried both two half days and ‘full’ days of various lengths. Our experience is that one full day of 6–7 h is better than two half days. This is because it takes time for the participants to get into ‘the mode’. For role-plays, one might consider the use of professional actors as simulated patients [Citation49,Citation61]. However, based on experience from prior projects [Citation25], we wanted the participating physicians to act as both physicians and patients to let them experience both sides of the table.

Someone outside the clinic management should perform the coaching. Securing non-disclosure is important, as is a safe, non-judgmental environment. We also learned that patients are not gatekeepers; all patients allowed an observant to participate in the consultation.

| (4) | Expect resistance and skepticism | ||||

Although expected, the resistance and skepticism among the physicians caught us somewhat off guard. After having attended the lectures focusing on the background and aim of the PALLiON project, some of the experienced physicians came to the discussion groups expressing the feeling that we accused them of being too focused on anti-cancer treatment and not being good communicators. We listened carefully to this feedback prior to discussing in the faculty meetings how to address it further. We decided that it was important to meet this feedback with tolerance and understanding; we certainly did not aim to be judgmental. At the same time, we knew that current practice could and should be improved. We chose to address this in the groups and were open to discussions about this with the participants. Moreover, we emphasized the goal of ‘becoming better’ instead of ‘good’, trying to diminish the perceived negative evaluation of their current practice. We also focused on the fact that clinical communication is a set of skills that needs to be learned and practiced, like all other clinical skills in medicine [Citation17,Citation19].

The encouraging evaluation and the positive informal feedback we received might illustrate a shift from skepticism to somewhat more positivity regarding the educational program. Overall, residents expressed less resistance. Age and experience might be negatively associated with open-mindedness, for such programs. Culture also seems to be an important factor here [Citation62,Citation63], while resistance was substantial at some hospitals; it was met with open arms elsewhere.

For the successful execution of communication skills training, we believe it is essential that at least one experienced teacher leads the groups. The teacher must be able to handle resistance and lead the group firmly when necessary, but at the same time be participant-centered in his or her approach and facilitate discussions in which different opinions are expressed.

| (5) | Team up with the management, but more importantly, the gatekeepers | ||||

We learned that managerial support is pivotal for the successful implementation of such a complex program. Even more important is teaming up with the informal gatekeepers. In the aftermath, we recognize that involving the gatekeepers and other clinicians to a greater extent would have been more inclusive and probably reduced the resistance. Yet, by including local PIs throughout the process, we may have facilitated implementation, despite their limited training.

| (6) | Expect time to fly | ||||

It is a long process to develop a complex educational program. It is even more time-consuming to implement and complete. In addition, clinicians often have limited time to dedicate to educational purposes. Our opinion is that group sessions need to be mandatory and organized by the management. Another factor that extended the completion was the high turnover among residents at all hospitals, which results from the organization of specialist training in Norway. Because of this, we had to repeat the educational program for new employees on multiple occasions.

| (7) | Plan thorough assessment of evaluation and effect | ||||

Program evaluation should be planned rigorously and early in the process of development. We conducted an ad-hoc evaluation of parts of the program. However, we realize that a more substantial evaluation should have been a high priority and planned from the start, despite the challenges, given the relatively tight timeframe in the PALLiON project. Assessment of effect such as measurement of the changes in participants’ communication behavior is resource demanding, but desirable. Optimally, evaluation of the potential long-term effects should have been included in such an evaluation. This requires that the group of clinicians remain stable over time.

Conclusion

The PALLiON educational program was developed to improve physicians’ skills in providing advanced cancer care in a model of integrated, patient-centered oncology and palliative care. A multi-faceted, needs and evidence-based program with a specific focus on communication skills is demanding, but feasible to develop and implement. There are several barriers and facilitators influencing implementation success and sustainability. We have learned several lessons throughout the process to be considered in similar future projects. The seven take-home messages may be part of a framework in an implementation science program for successful uptake in clinical practice.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The PALLiON project is conducted in accordance with ethical principles according to the Declaration of Helsinki. It is further in accordance with Good Clinical Practice and all Norwegian regulatory requirements for study conduct. Ethical approval was confirmed by the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics in SouthEast Norway (REC) 14.12.2016 (RefID: 2016/1220-PALLiON). Written consent to participate in the PALLiON project was collected from patients and carers as requested by the REC.

Acknowledgements

We thank Kjersti Støen Grotmol, Hege Oma Ohnstad, and the section of medical informatics, faculty of medicine, University of Oslo, for invaluable contributions to the development of the educational program.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Tonje Lundeby

Tonje Lundeby, MSc, PhD, is a researcher and the administrative manager of the European Palliative Care Research Centre (PRC).

Arnstein Finset

Arnstein Finset; PhD, is a psychologist and professor emeritus at the Department of Behavioural Sciences in Medicine at University of Oslo (UiO).

Stein Kaasa

Stein Kaasa, MD, PhD, is a professor in Palliative Medicine at UiO and head of the Oncology Department at Oslo University Hospital (OUH). He is also the director of PRC.

Torunn Elin Wester

Torunn Elin Wester, MSc, is head of the Advisory Unit on Palliative Care at OUH.

Marianne Jensen Hjermstad

Marianne Jensen Hjermstad, MSc, PhD is a researcher at PRC and UiO.

Olav Dajani

Olav Dajani, MD, PhD, is a consultant at the Department of Oncology, OUH, and researcher at PRC.

Erik Wist

Erik Wist, MD, PhD, is a professor emeritus at the Institute of Clinical Medicine, UiO.

Nina Aass

Nina Aass, MD, PhD, is a professor in Palliative Medicine at UiO, and Head of the Section of Palliative Medicine at the Department of Oncology, OUH.

References

- Smith TJ, Temin S, Alesi ER, et al. American society of clinical oncology provisional clinical opinion: the integration of palliative care into standard oncology care. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(8):880–887.

- Ferrell BR, Temel JS, Temin S, et al. Integration of palliative care into standard oncology care: American society of clinical oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2016;70:1474.

- Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, et al. Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. 2014;383(9930):1721–1730.

- Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):733–742.

- Maltoni M, Scarpi E, Dall’Agata M, et al. Systematic versus on-demand early palliative care: a randomised clinical trial assessing quality of care and treatment aggressiveness near the end of life. Eur J Cancer. 2016;69:110–118.

- Kaasa S, Loge JH, Aapro M, et al. Integration of oncology and palliative care: a Lancet oncology commission. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(11):e588–e653.

- Clayton JM, Hancock KM, Butow PN, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for communicating prognosis and end-of-life issues with adults in the advanced stages of a life-limiting illness, and their caregivers. Med J Aust. 2007;187(8):478.

- Parker SM, Clayton JM, Hancock K, et al. A systematic review of prognostic/end-of-life communication with adults in the advanced stages of a life-limiting illness: patient/caregiver preferences for the content, style, and timing of information. J Pain Sympt Manage. 2007;34(1):81–93.

- Bolognesi D, Centeno C, Biasco G. Official specialization in palliative medicine. An European study on programs features and trends. Palliat Med. 2014;28(6):668–669.

- Gilligan T, Bohlke K, Baile WF. Patient-clinician communication: American society of clinical oncology consensus guideline summary. J Oncol Pract. 2018;14(1):42–46.

- Cherny N, Catane R, Kosmidis P. ESMO takes a stand on supportive and palliative care. Ann Oncol. 2003;14(9):1335–1337.

- Grol R, Grimshaw J. From best evidence to best practice: effective implementation of change in patients’ care. Lancet. 2003;362(9391):1225–1230.

- Sommerbakk R, Haugen DF, Tjora A, et al. Barriers to and facilitators for implementing quality improvements in palliative care – results from a qualitative interview study in Norway. BMC Palliat Care. 2016;15(1):61.

- Zhi WI, Smith TJ. Early integration of palliative care into oncology: evidence, challenges and barriers. Ann Palliat Med. 2015;4(3):122–131.

- Von Roenn JH, Voltz R, Serrie A. Barriers and approaches to the successful integration of palliative care and oncology practice. J Natl Compr Cancer Network. 2013;11(suppl 1):11–16.

- Lundeby T, Wester TE, Loge JH, et al. Challenges and learning needs for providers of advanced cancer care: focus group interviews with physicians and nurses. Palliat Med Rep. 2020;1(1):208–215.

- Back AL, Fromme EK, Meier DE. Training clinicians with communication skills needed to match medical treatments to patient values. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(S2):S435–S441.

- Back AL, Michaelson K, Alexander S, et al. How oncology fellows discuss transitions in goals of care: a snapshot of approaches used prior to training. J Palliat Med. 2010;13(4):395–400.

- Stiefel F, Barth J, Bensing J, et al. Communication skills training in oncology: a position paper based on a consensus meeting among European experts in 2009. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(2):204–207.

- Fallowfield L, Jenkins V, Farewall V, et al. Efficacy of a cancer research UK communication skills training model for oncologists: a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. 2002;359(9307):650–656.

- Baker A., and Institute of Medicine (IOM). Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Br Med J. 2001;323(7322):1192.

- Brown RF, Bylund CL, Gueguan JA, et al. Developing patient-centered communication skills training for oncologists: describing the content and efficacy of training. Commun Educ. 2010;59(3):235–248.

- Bylund CL, Brown RF, Bialer PA, et al. Developing and implementing an advanced communication training program in oncology at a comprehensive cancer center. J Cancer Educ. 2011;26(4):604–611.

- Pham AK, Bauer MT, Balan S. Closing the patient–oncologist communication gap: a review of historic and current efforts. J Cancer Educ. 2014;29(1):106–113.

- Finset A, Ekelberg O, Aspegren K. Long term benefits of communication skills training for cancer doctors. Psychooncology. 2003;12(7):686–693.

- Aldridge MD, et al. Education, implementation, and policy barriers to greater integration of palliative care: a literature review. Palliat Med. 2016;30(3):224–239.

- Back AL, Arnold RM, Baile WF, et al. Efficacy of communication skills training for giving bad news and discussing transitions to palliative care. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(5):453–460.

- Hjermstad MJ, Aass N, Andersen S, et al. PALLiON – PALLiative care integrated in ONcology: study protocol for a Norwegian national cluster-randomized control trial with a complex intervention of early integration of palliative care. Trials. 2020;21(1):303.

- Brown RF, Bylund CL. Communication skills training: describing a new conceptual model. Acad Med. 2008;83(1):37–44.

- Frankel RM, Stein T. Getting the most out of the clinical encounter: the four habits model. Perm J. 1999;3(3):79–88.

- Baile WF, Buckman R, Lenzi R, et al. SPIKES-A six-step protocol for delivering bad news: application to the patient with cancer. Oncologist. 2000;5(4):302–311.

- Kurtz S, Silverman J, Benson J, et al. Marrying content and process in clinical method teaching: enhancing the Calgary-Cambridge guides. Acad Med. 2003;78(8):802–809.

- Stiggelbout AM, Van der Weijden T, De Wit MP, et al. Shared decision making: really putting patients at the centre of healthcare. BMJ. 2012;344:e256.

- Elwyn G, Forsch D, Thomson R, et al. Shared decision making: a model for clinical practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(10):1361–1367.

- Goelz T, Wuensch A, Stubenrauch S, et al. Specific training program improves oncologists’ palliative care communication skills in a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(25):3402–3407.

- Moore PM, Mercado SR, Artigues MG, et al. Communication skills training for healthcare professionals working with people who have cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013(3):CD003751.

- Jenkins V, Fallowfield L, Saul J. Information needs of patients with cancer: results from a large study in UK cancer centres. Br J Cancer. 2001;84(1):48–51.

- Fallowfield LJ, Jenkins VA, Beveridge H. Truth may hurt but deceit hurts more: communication in palliative care. Palliat Med. 2002;16(4):297–303.

- Institute of Medicine. Dying in America: improving quality and honoring individual preferences near the end of life. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2015.

- Detmar SB, Muller MJ, Schornagel JH, et al. Role of health-related quality of life in palliative chemotherapy treatment decisions. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(4):1056–1062.

- Baile WF, Aaron J. Patient-physician communication in oncology: past, present, and future. Curr Opin Oncol. 2005;17(4):331–335.

- Tulsky JA, Beach MC, Butow PN, et al. A research agenda for communication between health care professionals and patients living with serious illness. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(9):1361–1366.

- Thorne SE, Bultz BD, Baile WF. Is there a cost to poor communication in cancer care? A critical review of the literature. Psychooncology. 2005;14(10):875–884.

- Back AL, Arnold RM. Discussing prognosis: “how much do you want to know?” Talking to patients who are prepared for explicit information. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(25):4209–4213.

- Thomas AA, Carver A. Essential competencies in palliative medicine for neuro-oncologists. Neurooncol Pract. 2015;2(3):151–157.

- Hui DBE. Integrating palliative care into the trajectory of cancer care. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2016;13(3):159–171.

- Rawlings D, Tieman JJ, Sanderson C, et al. Never say die: death euphemisms, misunderstandings and their implications for practice. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2017;23(7):324–330.

- Davis DA, Mazmanian PE, Fordis M, et al. Accuracy of physician self-assessment compared with observed measures of competence: a systematic review. Jama. 2006;296(9):1094–1102.

- Berkhof M, Van Rijssen HJ, Schellart JR, et al. Effective training strategies for teaching communication skills to physicians: an overview of systematic reviews. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;84(2):152–162.

- Cegala DJ, Post DM. The impact of patients’ participation on physicians’ patient-centered communication. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;77(2):202–208.

- Walczak A, Butow PN, Bu S, et al. A systematic review of evidence for end-of-life communication interventions: who do they target, how are they structured and do they work? Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99(1):3–16.

- Uitterhoeve RJ, Bensing JM, Grol RP, et al. The effect of communication skills training on patient outcomes in cancer care: a systematic review of the literature. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2010;19(4):442–457.

- Beeson SJNC. Physician coaching: clinicians helping clinicians on the things that matter most. NEJM Catal. 2017;3:6.

- Wuensch A, Goelz T, Ihorst G, et al. Effect of individualized communication skills training on physicians’ discussion of clinical trials in oncology: results from a randomized controlled trial. BMC Cancer. 2017;17(1):264.

- Ammentorp J, Graugaard LT, Lau ME, et al. Mandatory communication training of all employees with patient contact. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;95(3):429–432.

- Wolderslund M, Kofoed PE, Ammentorp J. The effectiveness of a person-centred communication skills training programme for the health care professionals of a large hospital in Denmark. Patient Educ Couns. 2021;104(6):1423–1430.

- Grol R, Wensing M. What drives change? Barriers to and incentives for achieving evidence-based practice. Med J Aust. 2004;180(S6):S57–S60.

- Lundeby T, Hjermstad MJ, Aass N, et al. Integration of palliative care in oncology – the intersection of cultures and perspectives of oncology and palliative care. In Press: eCancer. 2022.

- Kurtz S, Draper J, Silverman J. Teaching and learning communication skills in medicine. 2nd Edition. London: CRC Press; 2004.

- Silverman J, Kurtz S, Draper J. Skills for communicating with patients. 3rd Edition. London: CRC Press; 2013.

- Lane C, Rollnick S. The use of simulated patients and role-play in communication skills training: a review of the literature to August 2005. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;67(1-2):13–20.

- Visser A, Wysmans M. Improving patient education by an in-service communication training for health care providers at a cancer ward: communication climate, patient satisfaction and the need of lasting implementation. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;78(3):402–408.

- Perron NJ, Sommer J, Hudelson P, et al. Clinical supervisors’ perceived needs for teaching communication skills in clinical practice. Med Teach. 2009;31(7):e316–e322.