ABSTRACT

Background and goal:

Marginalized patients often feel unwelcome in healthcare. The concept of culturally safe healthcare (CSH) represents an important paradigm shift from provider control to patients who feel safe voicing health concerns and believe that they are heard by providers. This study has five goals: review works describing CSH, identify CSH themes, describe provider behaviors associated with CSH, describe interventions, and discuss how health communication can advance CSH.

Methods:

A scoping review was conducted for articles published between 2019 and 2023 following modified PRISMA guidelines. Online databases included Pubmed (Medline), CINAHL, Web of Science, Google Scholar, and Redalyc. Thematic analysis was also conducted.

Results:

Twenty-one articles meeting inclusion criteria were identified and analyzed. Of these, five explained features of CSH, four were empirical studies, seven were content analyses, and five were interventions. Five themes were identified including (1) how patients perceive CSH, (2) sociocultural determinants of health inequity, (3) mistrust of care providers, (4) issues with the biomedical model of healthcare, and (5) the importance of provider-patient allyship. Care provider communication behaviors fostering CSH were discussed. Three CSH interventions were highlighted. Finally, there was a discussion for how health communication scholars can contribute to CSH.

Conclusions:

CSH offers a paradigm shift from provider control to marginalized patients’ experience of patient-provider communication. Recommendations for how health communication scholars can contribute to the implementation of CSH included developing guiding theories and measurement, evaluation of CSH outcomes, and conducting focus groups with patients to assess the meaning of cultural safety.

Introduction

In the 1990s, midwives witnessing birthing harms to indigenous women in Australia and New Zealand called for culturally safe healthcare for women who were often mistreated during childbirth [Citation1]. More recently, the concept of culturally safe healthcare for underserved patients has extended to other marginalized groups and to health conditions beyond childbirth. Marginalized refers to people ‘whose needs and experiences are overlooked and who have limited resources and power due to facets of their identity’ [Citation2, p. 1]. Culture refers to groups that a person identifies with and the history that they share based on race, ethnicity, age, gender, stigma, ableism, education, religion, socio-economic status, or combinations of these identities [Citation3]. Intersectionality describes the impact of overlapping identities with differing emotional, psychological, and social resource demands which shape responses to life experiences [Citation4]. In addition to problems posed by global health inequities and medical stigma and racism, competing demands experienced by marginalized patients may block their agency and self-determination over healthcare choices [Citation5].

Culturally safe healthcare (CSH) represents a major conceptual paradigm shift from care provider dominance and control over patients in marginalized groups to patient self-empowerment in being heard and obtaining needed care in clinical encounters. People in marginalized groups who have experienced previous medical mistreatment have the right to feel physically, emotionally, and spiritually safe when they seek healthcare. Culturally safe care is defined as

critical consciousness where healthcare professionals and organizations engage in ongoing self-reflection and self-awareness and hold themselves accountable for providing culturally safe care, as defined by the patient and their communities, and as measured through progress towards achieving health equity [Citation6, p. 14].

There has been extensive interest in the field of health communication in collaborative approaches to healthcare including encouraging patient agency in care management [Citation7], shared decision making [Citation8], patient-centered communication [Citation9], cultural humility [Citation10], and cultural competence/sensitivity [Citation11]. These concepts based on allyship and collaboration focus on communication choices made by care providers to be more inclusive of patients. They are important steps in recognizing the needs of marginalized patients for cultural safety in seeking healthcare [Citation12]. These approaches emphasize provider choices about how to communicate with patients rather than patient choices.

By comparison, in culturally safe healthcare, it is the patient who has agency and self-determination in deciding whether provider communication is compassionate, empathetic and responsive not the care provider. This can be a humbling realization for care providers [Citation13]. CSH examines patient perceptions of providers’ attempts to be patient-centered and whether patients’ circumstances enable them to carry out a care plan even if they had a hand in making the plan. For marginalized patients this perception of provider empathy and shared decision-making is often shaped by a deep legacy of historical medical abuse, the experience of a lifetime of substandard care, and medical mistrust based on previous bad encounters with medical providers not just for themselves but for other members of their group, friends and family members.

Even though discussion of culturally safe healthcare has been available for many years, this concept is just beginning to gain currency in medical education and health policy to define allyship between marginalized patients and their providers. There are multiple questions about conceptualizing, implementing, and assessing cultural safety and what cultural safety means to patients. When there is uncertainty about the meaning of an emergent construct, when interventions are just starting to be implemented, and when CSH health outcome data are not yet available, a scoping review is the optimal review procedure [Citation14]. The goals of this scoping review are to identify and review relevant works on CSH, to derive themes characterizing this construct, to discuss how communication can foster a response of cultural safety especially focusing on care provider communication behaviors, to describe interventions intended to teach CSH, and to recommend how health scholars can advance this construct. These questions were investigated.

RQ1: What features characterize CSH?

RQ2: What themes characterize CSH?

RQ3: What care provider communication behaviors encourage feelings of cultural safety?

RQ4: What interventions have been conducted to promote CSH?

RQ5: How can health communication scholars contribute to advancement of CSH?

Method

Procedure

The current review was conducted following revised PRISMA guidelines modified for scoping reviews when evidence for outcomes is limited [Citation15]. Articles had to meet the following criteria to be included: (1) the focus of the article should be on CSH; (2) be based on one of the following methods: theoretical/conceptual article, be a quantitative or qualitative study; and (3) be published during the last 5 years (between 2019 and June 2023). Search terms were developed by the authors in consultation with a reference librarian using combinations of these terms: ‘culturally safe healthcare,’ ‘cultural safety,’ ‘medical racism,’ and ‘health equity.’ Online databases searched included Pubmed (Medline), CINAHL, Web of Science, Google Scholar, and Redalyc. Selection of databases was guided by those used in previous reviews of culturally safe birthing care. References listed in recent articles and the content of five earlier CSH scoping reviews were also examined [Citation16–20]. No ethics/institutional research approval or consent was required as this scoping review did not involve human subjects.

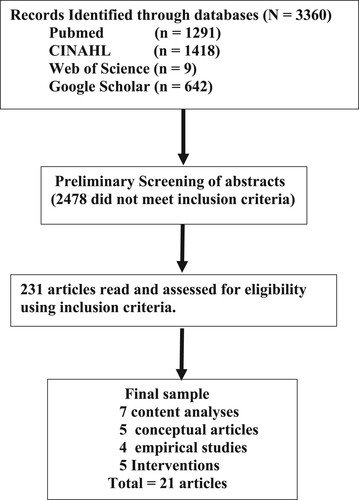

As shown in , the search yielded 3360 articles. Duplicates and articles that did not mention CSH in the title, abstract, or keywords were removed yielding a sample of 231 articles. Following this, a second screening of the 231 articles was conducted based on reading the text. From this group, 210 additional articles were excluded as they only mentioned cultural safety as a social determinant, described hospital safety culture practices rather than CSH, or focused on barriers experienced by marginalized groups outside of the healthcare context. This left a final sample of 21 articles.

Content analysis [Citation21] was used to derive CSH themes following these steps: identify properties of frequently mentioned experiences of CSH; give each CSH theme a unique descriptor; continue to identify CSH themes until saturation is reached where no new themes are identified; and condense CSH categories into a body of themes that can be replicated. Following this procedure, a list of 18 categories describing the CSH content of these articles was compiled. The coauthors then met and discussed these categories which by mutual agreement were condensed into five themes showing relevance to culturally safe healthcare.

provides a descriptive overview of articles included in this review showing the year and source of publication, country that was the focus, type of study, participants/type of data, and a brief summary of important findings. All articles were published during the last 5 years: six published in 2022, five in 2021, two in 2020, and eight in 2019. Discussion of CSH predominantly occurred in medical and nursing journals. The majority of discussions focused on culturally safe healthcare in Canada and Australia but eight other countries were also included. Five articles were conceptual discussions of CSH, four were empirical studies, seven were content analyses, and five were CSH educational interventions.

Table 1. Summary of studies on culturally safe healthcare (CSH).

Results

RQ1. Descriptions of culturally safe healthcare

Research question 1 asked how CSH features were described. Patient descriptions of CSH are presented chronologically in . These features emphasize the centrality of marginalized patients and their perceptions in determining whether and when healthcare is judged to be culturally safe. These descriptions suggest that continuing to conduct the practice of medicine as usual without sufficient thought being given to the need for culturally safe care is likely to perpetuate health inequities which makes marginalized people feel unwelcome in clinical encounters with providers where they often receive disrespectful, substandard care.

Table 2. Features of culturally safe healthcare and medical racism presented chronologically.

RQ2. Themes of culturally safe healthcare research

The second research question addressed the themes of CSH research to date. Five CSH themes were identified including: (1) marginalized patient perceptions of care provider communication, (2) social and cultural determinants contributing to health inequity, (3) patient mistrust of care providers, (4) issues with the biomedical model of healthcare, and (5) patient-care provider allyship.

Theme 1: marginalized patient perceptions of care provider communication

Provider communicative behaviors have an immediate impact on all patients especially marginalized patients who may have experienced negative clinical encounters in the medical system. Marginalized patients described clinical encounters with care providers as often being one-sided, quiet and lonely places where they were relegated to their own communication silence and experienced social and cultural rejection. Provider communication was seen as intimidating, unaccepting, and prejudicial [Citation22]. Effective healthcare providers were characterized as those who encouraged patients to talk about things that worried them without shutting down communication. Caring health providers showed warmth, inclusiveness, and information clarity. They were perceived by marginalized patients as really listening, being responsive to their needs, and trying to build a trusting communicative relationship with them [Citation23].

Theme 2: social and cultural determinants contributing to health inequity

Providers need to be aware that there is a history of racial inequity in all social domains including medicine. Hardeman et al. [Citation24] argued that the root cause of health inequity was institutional racism. In order to demonstrate this claim, they conducted a systematic review of 249 medical and public health journals from 2002 to 2015 searching for the term institutional racism finding only 25 articles explicitly mentioning institutional racism in medicine. They argued that failure to publicly name institutional racism diminished the ability of the health field to address deep causes of racial health inequities at the institutional, interpersonal, and internal levels and results in culturally unsafe healthcare for marginalized patients.

Theme 3: patient mistrust of care providers

Williamson et al. [Citation25] examined the relationship between racial discrimination and medical mistrust. Their goal was to identify antecedents of medical mistrust. They conducted an experimental study measuring medical mistrust, direct and vicarious experience of discrimination, ethnic identity, and linked fate with characters in a news story. Black participants reported significantly more medical mistrust compared to White participants and medical mistrust was associated with prior personal and vicarious experience of discrimination.

Inclusiveness can be shown in something as simple as displays of race-ethnic diverse clientele in pictures posted in medical offices which may help patients to anticipate better-quality care [Citation26]. These findings are important as people who have experienced medical discrimination based on race, ethnicity, religion, gender, or ableism have been shown to be less likely to seek preventative healthcare compounding the problem of health disparities and inequity [Citation26].

Theme 4: issues with the biomedical model of healthcare

The biomedical model teaches healthcare providers to see people as bodies with pathologies and to find solutions for bodily malfunction. This often results in marginalized patients health problems being attributed to bad behavioral choices, inadequate preventive healthcare or lack of medical compliance. Medical pedagogy often does not include discussion of racial justice in healthcare [Citation27]. Interventions asking care providers to confront injustice and medical racism may result in attitudinal and behavioral change, but may also cause psychological reactance and rejection of the content of the intervention, and while such training may make a difference for one provider, it is likely to have minimal impact on how medicine is conducted with marginalized groups.

Using narratives of provider success in dealing with cultural needs of marginalized patients as part of provider training has been shown to reduce provider reactance and counterarguing, and increase positive affect and feelings of self-efficacy in working with marginalized patients [Citation28]. Care providers are often the first responders to marginalized patients in fighting health inequities.

Theme 5: patient-care provider allyship

The final theme characterizing these articles is the need for building allyship between care providers and patients. Noone et al. [Citation29] asked what it means to be an ally in confronting medical oppression. Twelve physicians educators were trained to run allyship interventions with hospital staff. The interventions aimed to increase recognition of the impact of provider power and privilege, reduce microaggressive communication, and establish allyship with care recipients with good interpersonal and health outcomes.

RQ3. Provider behaviors and communication with patients

In response to research question 3, provider communication behaviors contributing to perception of inclusive communication included care providers who focused on patient emotional needs not just health information exchange, who engaged in attentive listening, showed awareness of possible microaggressive communication, recognized the inherent power imbalance in clinical settings, asked about how the illness affects the patient’s ability to care for their family, showed understanding that there may be issues of trust, and who asked whether the patient was able to carry out the course of treatment given their other demands [Citation30–35].

RQ4. Interventions to implement culturally safe healthcare

The fourth research question asked about interventions to implement CSH. Interventions should include feedback from healthcare staff, patients, and health system researchers to build allyship for health equity [Citation36]. Two CSH interventions are presented because they embrace community partnership and view collaboration between researchers and practitioners as an integral part of medical education and CSH.

Sanyas is an innovative educational intervention addressing racism and the need for cultural safety in all sectors including justice, child welfare, education, government, and health [Citation37]. San’yas is a Kwak’wala word meaning practical knowledge. The Sanyas intervention was designed to address inequitable power, racism reduction, and stigma experienced by marginalized people. For example, one course is entitled ‘Bystander to Ally’ teaching participants how to respond to others who show bias and how to advocate for social justice. Coaching for leaders to reduce racism and gaps in health equity was also provided. Over 125,000 care providers in Canada have received this training.

In 2022, 268 Colombian medical students engaged in a CSH game jam where they were instructed to create a game on cultural safety [Citation38]. Health game jams are an innovative, engaging way for learners to become involved in a new concept. During the 8-hour game jam session, students developed and then played each other’s game designed to teach elements of cultural safety. So, for example, the imposition of biomedicine over traditional practices was treated as culturally unsafe. Students reported positive response to the CSH game jam intervention but no evidence of behavioral change for CSH was measured. While training providers is a necessary first step, the impact of structural racism continues to pose problems for dismantling health inequities. Several sources included in this review advocated that care provider training include courses and in-service workshops addressing culturally safe care and health justice [Citation39–43].

RQ5. What work still needs to be done?

The final research question asked what work still needs to be done to advance conceptualization, implementation, and evaluation of CSH. Federal to community public health organizations must include diverse voices on their advisory and medical review boards for public accountability. As CSH is scaled up in many health systems, data for patient satisfaction and whether improved health outcomes can be linked to CSH needs to be collected.

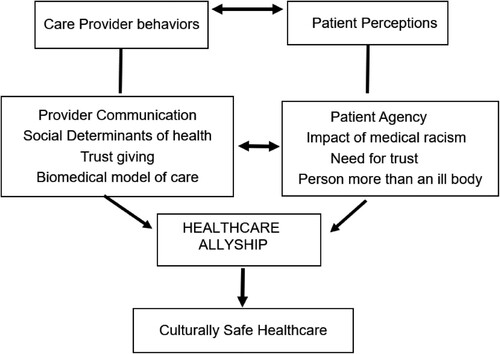

An extensive database search for articles treating culturally safe healthcare yielded only a few articles in Communication journals specifically discussing culturally safe healthcare with the lead taken by medical and nursing journals promoting this construct. Scholars trained in health communication can bring theoretical and methodological expertise to examination of care provider communication and offer methodology for rigorous evaluative research. As in the beginning model proposed (See ), they can create structural equation models to identify and test causal relationships among components of CSH. They can develop and validate scales to measure these components. They can systematically evaluate evidence for the efficacy of CSH interventions with both care provider behaviors and care recipient responses. They can conduct longitudinal studies of community health programs based on CSH. Health communication scholars can also conduct comparative examination of the advantages of various CSH message effects and identify and test the best channels to deliver such messages. They can create websites and apps to promote CSH.

This rigorous development and evaluation is needed for CSH to move forward. More work needs to be conducted to understand what marginalized patients see as culturally safe healthcare. Communication scholars can ask marginalized patients in focus groups to identify what cultural safety in healthcare means to them.

Discussion

These articles on CSH show that care providers must have awareness that marginalized patients often believe that they receive substandard care and may feel mistrust for providers. Provider indifference, intimidation, and negligent care are barriers to CSH. This mistrust is compounded by institutional and medical racism and racial injustice. In this context of chronic mistrust, patients may withhold important information due to fear that they will be judged negatively by providers or they may opt out of care entirely delaying life-saving treatment. The care provider has diagnostic expertise but must suspend cultural stereotypes about marginalized patients who enter healthcare with guarded expectations. CSH is based on patients’ perceptions of care providers attentiveness and respect for them. Health systems must also be committed to supporting care providers with sufficient resources to create a climate where CSH can be realized.

For example, the Patient Health Engagement Model [Citation44] charted a course for the necessity for turning patients into protagonists in informed, shared decision making about their care choices. The model argued for creating a patient-provider relational agenda for increasing engagement and allyship in joint medical decision making. While marginalized patients often face multiple institutional, historical, and identity barriers to their own agency in health engagement, this model is insightful for understanding where culturally safe healthcare may find a foothold for enhancing trust and beginning to restore belief in the possibility of equity in healthcare.

Practical implications for patient-provider communication and allyship

In the U.S., there is a troubling, deep-seated history of medical abuse and racism toward Black men and women [Citation45] and Native Americans [Citation46] which has resulted in intergenerational medical mistrust. The harsh reality of healthcare in the U.S. is that marginalized patients often live with food insecurity in maternity, clinical, and social media deserts where access to equitable care is absent [Citation47]. Their marginalized status is underscored by hospitals in challenged neighborhoods that are often over-crowded, under-staffed, ill-equipped and substandard with the best physicians choosing to practice elsewhere. Marginalized patients clearly understand that care is not equitable for them. They may be unable or mistrustful in carrying out provider-controlled treatment options. There are several antecedent constructs to culturally safe healthcare. For example, health provider communication accommodation with patients signals the need for information exchange, shared decision making, and ability to read affective cues in response to provider communication [Citation48].

An approach to health seeking based on patient perceptions of cultural safety offers an alternative, innovative route to achieve social justice and to address embedded health inequities often perpetuated through current approaches which center on behaviors and interventions created and controlled by care providers and health care systems. Further work needs to be done to assess what cultural safety in healthcare means to marginalized patients and their communities.

Allyship between patients and providers is based on awareness of the marginalized patient’s unique set of circumstances and their ability and concerns for engaging in treatment. Culturally safe healthcare focuses on balancing the power between provider and patient. Increasing provider awareness of health inequities can happen through racial justice education. While training providers is a necessary first step, the impact of structural racism continues to pose problems for dismantling health inequities. Health organizations need to include diverse voices on their advisory and medical review boards and in their policy documents for public accountability [Citation49].

CSH offers a portal for rethinking normative healthcare in western biomedicine recognizing the detrimental effects of power imbalance and historical and medical racism [Citation50, Citation51]. So, how can this situation be addressed? While much effort has been put into CSH education and policy change in health organizations, evidence needs to be gathered for whether there is patient satisfaction and improved health outcomes linked to CSH. Hoffman-Longtin et al. [Citation52] argued against being entrenched in disciplinary silos and instead called for health communication boundary spanning among researchers and practitioners working in a variety of fields including nursing, health communication and psychology, medicine, pharmacy care, public health, midwifery, and social work. Achieving health equity must be a collaborative endeavor across all stakeholders, health organizations, and communities.

Part of the difficulty in advancing CSH is that development of a unitary theory of culturally safe healthcare has lagged. A more robust articulation of CSH theory would help to guide training and health evaluation outcome research and give guidance to care providers about the role of their verbal and nonverbal communication in patient perception of cultural safety. Based on the recommendations in the articles included in this review, an integrative model for the Communication of Culturally Safe Healthcare is proposed (), as an important first step in identifying and testing antecedents of culturally safe healthcare. Future studies might build on this model to test how communication in the clinical encounter affects patient satisfaction and health outcomes of CSH.

Limitations

CSH was originally developed by midwives for birthing care of marginalized women. A number of previous integrative and scoping reviews have examined cultural safety in perinatal care [Citation17,Citation18]. This construct was extended to consider how people in underserved groups experience broader forms of healthcare beyond these birthing studies. CSH provides a pathway for global rethinking of patient agency and empowerment in healthcare around the world. This study focused primarily on articles developing the CHS construct that met inclusion criteria. Only five training interventions were included in this review. There are many other descriptions of CSH interventions. An initial predictive model was proposed which needs refinement and testing. Finally, the extent to which healthcare systems have revised policy to include patient agency and self-determination was not examined in this review.

Conclusions

This scoping review systematically identified what CSH means for marginalized patients and providers as well as identifying gaps in existing knowledge, implementation, and evaluation of CSH. While the studies in this review were informative, they gathered no evidence of behavioral change based on hospital policy, provider training, or patient evaluations. Whether and how implementation of CSH makes a difference remains to be demonstrated. CSH shifts the lens from provider centrism in clinical care to patient agency and self-empowerment in obtaining equitable care. Health communication scholars are positioned to make important contributions in this effort. CSH opens up the scholarly dialogue on the seismic effects of institutional and medical racism in healthcare. This discussion is a critical first step in achieving health equity.

Ethical approval

This study is a scoping review of existing literature and did not involve human participants.

Author contributions

The first author conducted the initial screening of sources. The remaining sources were divided between the co-authors for additional screening and reading of the texts. Both authors contributed to reading and analyzing the sources.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the contribution of Iris Kovar-Gough, Liaison Librarian to the Michigan State University College of Human Medicine, in helping to conduct the database reviews. We also thank our colleagues, Joanne Goldbort and Elizabeth Bogdan-Lovis, for their feedback on the early stages of this project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data are available from the corresponding author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Mary Bresnahan

Mary Bresnahan (Ph.D., 1985, University of Michigan) is a Beal Professor and Professor Emeritus in the Department of Communication at Michigan State University. She conducts research on stigma and health, breastfeeding, and racial health equity.

Jie Zhuang

Jie Zhuang (Ph.D., 2014, Michigan State University) is an Associate Professor in the Department of Communication Studies at Texas Christian University. Her research interests lie in the intersection of health/risk communication and persuasion.

References

- Ramsden I, Whakaruruhau K. Cultural safety in nursing education in Aotearoa, New Zealand. Nurs Prax N Ze. 1993;8(3):4–10. doi:10.36951/NgPxNZ.1993.009

- Sannon S, Forte A. Privacy research with marginalized groups: what we know, what's needed, and what's next. Proc ACM Hum Comput Interact. 2022;6(4):1–33. doi:10.1145/3555556

- McGough S, Wynaden D, Gower S, Duggan R, Wilson R. There is no health without cultural safety: why cultural safety matters. Contemp Nurse. 2022;58(1):33–42. doi:10.1080/10376178.2022.2027254

- Crenshaw K. Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: a Back feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. In: Maschke K, editor. Feminist legal theories. Routledge; 2013. p. 23–51.

- Doran F, Wrigley B, Lewis S. Exploring cultural safety with nurse academics: research findings suggest time to “step up”. Contemp Nurse. 2019;55(2-3):156–70. doi:10.1080/10376178.2019.1640619

- Curtis E, Jones R, Tipene-Leach D, Walker C, Loring B, Paine SJ, et al. Why cultural safety rather than cultural competency is required to achieve health equity: a literature review and recommended definition. Int J Equity Health. 2019;18(1):1–7. doi:10.1186/s12939-019-1082-3

- O’Hair D, Villagran M, Wittenberg E, Brown K, Ferguson M, Hall HT, et al. Cancer Survivorship and Agency Model: implications for patient choice, decision making, and influence. Health Com. 2003;15(2):193–202. doi:10.1207/S15327027HC1502_7

- Elwyn G, Frosch D, Thomson R, Joseph-Willimas N, Lloyd A, Kinnersley P, et al. Shared decision making: a model for clinical practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(10):1361–7. doi:10.1007/s11606-012-2077-6

- Sheeran N, Jones L, Pines R, Jin B, Pamoso A, Eigeland J, et al. How culture influences patient preferences for patient-centered care with their doctors. J Commun Healthc. 2023;16(2), 186–96. doi:10.1080/17538068.2022.295098

- Schiavo R. Embracing cultural humility in clinical and public health settings: a prescription to bridge inequities. J Commun Healthc. 2023;16(2):123–5. doi:10.1080/17538068.2023.2221556

- Resnicow K, Baranowski T, Ahluwalia JS, Braithwaite RL. Cultural sensitivity in public health: defined and demystified. Ethn Dis. 1999;9(1):10-21. https://www.jstor.org/stable/45410142

- Bokhour BG, Fix GM, Mueller NM, Barker AM, Lavela SL, Hill JN, et al. How can healthcare organizations implement patient-centered care? Examining a large-scale cultural transformation. BC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):1–1. doi:10.1186/s12913-018-2949-5

- Rathert C, Williams ES, McCaughey D, Ishqaidef G. Patient perceptions of patient-centered care: empirical test of a theoretical model. Health Expect. 2015;18(2):199–209. doi:10.1111/hex.12020

- Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32. doi:10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O'Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73. doi:10.7326/M18-0850

- Brockie TN, Hill K, Davidson PM, Decker E, Krienke LK, Nelson KE, et al. Strategies for culturally safe research with Native American communities: an integrative review. Contemp Nurse. 2022;58(1):8–32. doi:10.1080/10376178.2021.2015414

- Cutajar L, Dahlen HG, Auwers AL, Berberovic B, Jedrzejewski T, Burns ES, et al. Model of care matters: an integrative review. Women Birth. 2023;36(4):315–26. doi:10.1016/j.wombi.2022.12.007

- Jennings W, Bond C, Hill PS. The power of talk and power in talk: a systematic review of Indigenous narratives of culturally safe healthcare communication. Aust J Prim Health. 2018;24(2):109–15. doi:10.1071/PY17082

- Marriott R, Strobel NA, Kendall S, Bowen A, Eades AM, Landes JK, et al. Cultural security in the perinatal period for Indigenous women in urban areas: a scoping review. Women Birth. 2019;32(5):412–26. doi:10.1016/j.wombi.2019.06.012

- Murphy L, Liu F, Keele R, Spencer B, Ellis KK, Sumpter D. An integrative review of the perinatal experiences of Black women. Nurs Womens Health. 2022;26(6):462–72. doi:10.1016/j.nwh.2022.09.008

- Morse JM, Bowers BJ, Charmaz K, Corbin J, Clarke AE, Stern PN. Developing grounded theory: the second generation (Vol. 3). London: Routledge; 2016.

- Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agénor M, Graves J, Linos N, Bassett MT. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. Lancet. 2017;389(1):1453–63. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30569-X

- Hosseinpoor AR, Bergen N, Kirkby K, Schlotheuber A. Strengthening and expanding health inequality monitoring for the advancement of health equity: a review of WHO resources and contributions. Int J Equity Health. 2023;22(1):1–9. doi:10.1186/s12939-022-01811-4

- Hardeman RR, Homan PA, Chantarat T, Davis BA, Brown TH. Improving the measurement of structural racism to achieve antiracist health policy: study examines measurement of structural racism to achieve antiracist health policy. Health Aff. 2022;41(2):179–86. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2021.01489

- Williamson LD, Smith MA, Bigman CA. Does discrimination breed mistrust? Examining the role of mediated and non-mediated discrimination experiences in medical mistrust. J Health Commun. 2019;24(10):791–9. doi:10.1080/10810730.2019.1669742

- Cipollina R, Sanchez DT. Racial identity safety cues and healthcare provider expectations. Stigma Health. 2020; 8(2):159–69. doi:10.1037/sah0000265

- Tsai J, Lindo E, Bridges K. Seeing the window, finding the spider: applying critical race theory to medical education to make up where biomedical models and social determinants of health curricula fall short. Front Public Health. 2021;9(1):1–10. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2021.653643

- Burgess DJ, Bokhour BG, Cunningham BA, Do T, Gordon HS, Jones DM, et al. Healthcare providers’ responses to narrative communication about racial healthcare disparities. Health Com. 2019;34(2):149–61. doi:10.1080/10410236.017.1389049

- Noone D, Robinson LA, Niles C, Narang I. Unlocking the power of allyship: giving healthcare workers the tools to take action against inequities and racism. NEJM Catalyst Innov Care Delivery. 2022;3(3):1–16. doi:10.1056/CAT.21.0358

- Pauly BB, McCall J, Browne AJ, Parker J, Mollison A. Toward cultural safety. Adv Nurs Sci. 2015;38(2):121–35. doi:10.1097/ANS.0000000000000070

- Lown BA, Muncer SJ, Chadwick R. Can compassionate healthcare be measured? The Schwartz Center compassionate care scale™. Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98(8):1005–10. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2015.03.019

- Mithen V, Kerrigan V, Dhurrkay G, Morgan T, Keilor N, Castillon C, et al. Aboriginal patient and interpreter perspectives on the delivery of culturally safe hospital-based care. Health Promot J Aust. 2021;32(1):155–65. doi:10.1002/hpja.415

- Muise GM. Enabling cultural safety in indigenous primary healthcare. Healthc Manage Forum. 2019;32(1):25–31. doi:10.1177/0840470418794204

- Radl-Karimi C, Nielsen DS, Sodemann M, Batalden P, von Plessen C. (2022). “When I feel safe, I dare to open up”: immigrant and refugee patients’ experiences with coproducing healthcare. Patient Educ Couns. 2022;105(7):2338–45. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2021.11.009

- Withall L, Ryder C, Mackean T, Edmondson W, Sjoberg D, McDermott D, et al. Assessing cultural safety in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health. Aust J Rural Health. 2021;29(2):201–10. doi:10.1111/ajr.12708

- Brumpton K, Ward R, Evans R, Neill H, Woodall H, McArthur L, et al. Assessing cultural safety in general practice consultations for indigenous patients: protocol for a mixed methods sequential embedded design study. BMC Med Ed. 2023;23(1):1–2. doi:10.1186/s12909-023-04249-6

- Browne AJ, Varcoe C, Ward C. San’yas Indigenous Cultural Safety Training as an educational intervention: promoting anti-racism and equity in health systems, policies, and practices. Int Indig Policy J. 2021;12(3):1–26. doi:10.18584/iipj.2021.12.3.8204

- Pimentel J, López P, Correal C, Cockcroft A, Andersson N. Educational games created by medical students in a cultural safety training game jam: a qualitative descriptive study. BMC Med Educ. 2022;22(1):1–9. doi:10.1186/s12909-022-03875-w

- Best O, Cox L, Ward A, Graham C, Bayliss L, Black B, et al. Educating the educators: implementing cultural safety in the nursing and midwifery curriculum. Nurse Educ Today. 2022;117(1):1–6. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2022.105473

- Maar M, McGregor L, Desjardins D, Delaney KZ, Bessette N, Reade M. Teaching culturally safe care in simulated cultural communication scenarios during the COVID-19 pandemic: virtual visits with indigenous animators. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2022;9(1):1–12. doi:10.1177/23821205221091034

- Rousseau C, Gomez-Carrillo A, Cénat JM. Safe enough? rethinking the concept of cultural safety in healthcare and training. Br J Psychiatry. 2022;221(4):587–8. doi:10.1192/bjp.2022.102

- Wylie L, McConkey S, Corrado AM. It’s a journey not a check box: indigenous cultural safety from training to transformation. Int J Indig Health. 2021;16(1):314–32. doi:10.32799/ijih.v16i1.33240

- Yaphe S, Richer F. Cultural safety training for health professionals working with indigenous populations in Montreal, Quebec. Int J Indig Health. 2019;14(1):60–84.

- Graffigna G, Barello S. Patient engagement in healthcare: pathways for effective medical decision making. Neuropsychol Trends. 2015;17(1):53–65.

- Washington HA. Medical apartheid: The dark history of medical experimentation on Black Americans from colonial times to the present. New York (NY): Doubleday Books; 2006.

- Brown-Rice K. Examining the theory of historical trauma among Native Americans. J Prof Couns. 2013;3(3):117–30. doi:10.15241/kbr.3.3.117

- Guo J, Dickson S, Berenbrok LA, etal Racial disparities in access to health care infrastructure across US counties: a geographic information systems analysis. Front Public Health. 2023;11(1):1–3. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2023.897007

- Watson B, Gallois C. Nurturing communication by health professionals toward patients: a communication accommodation theory approach. Health Commun. 1998;10(4):343–55. doi.org/10.1207/s15327027hc1004_3.

- Bozorgzad P, Peyrovi H, Vedadhir A, Negarandeh R, Esmaeili M. A critical lens on patient decision-making: a cultural safety perspective. Nurs Midwifery Stud. 2017;6(4):189–95. doi:10.4103/nms.nms_50_17

- Karbeah JM, Hardeman R, Almanza J, Kozhimannil KB. Identifying the key elements of racially concordant care in a freestanding birth center. J Midwif Womens Health. 2019;64(5):592–7. doi:10.1111/jmwh.13018

- Monchalin R, Smylie J, Nowgesic E. “I guess I shouldn’t come back here”: racism and discrimination as a barrier to accessing health and social services for urban Métis women in Toronto, Canada. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2020;7(2):251–61. doi:10.1007/s40615-019-00653-1

- Hoffmann-Longtin K, Kerr AM, Shaunfield S, Koenig CJ, Bylund CL, Clayton MF. Fostering interdisciplinary boundary spanning in health communication: a call for a paradigm shift. Health Com. 2022;37(5):568–76. doi:10.1080/10410236.2020.1857517