ABSTRACT

Initiated in Burgundy in the early fifteenth century by Colette of Corbie (1381–1447), the Colettine reforms soon expanded to eastern Iberia, reaching Portugal by the end of the century. In this paper I show how the context in which the first Colettine convents were founded in Portugal – a time when Clarissan reform was struggling to take the first steps in this territory and Colette’s endeavours were still a novelty – was reflected in the efforts developed by these communities and their patrons to promote a Colettine identity through the translation and use of a set of normative and para-normative texts, which would become the Colettines’ textual support in Portugal. I also demonstrate that these efforts were accompanied by the promotion of Colette of Corbie’s figure and sanctity through art.

Clarissan reform in a divided order

During the late Middle Ages, Europe witnessed the growth of Christian reform initiatives that, rooted in a discourse of crisis professing the decadence of religious life under vows, aimed to recover the lost rigour of monastic life. Backed by both the papacy and local powers, these initiatives, today broadly known as “Observant reforms,” reached several religious orders.Footnote1 Born within this environment, a more circumscribed movement, aimed at reforming the French Franciscan family, grew in Burgundy in the early fifteenth century, anchored in the figure of a young woman recluse from Corbie named Colette Boylet, who received a call to reform the order. Although sharing the same ideals of renewal, in contrast to what happened with the Observant reforms – promoted by the reformed branch of the Franciscans (the Observants), who increasingly wished to be independent from non-reformed Franciscans (the ConventualsFootnote2) – the Colettine reforms were born within the Franciscans’ conventual faction, rejecting the order’s fragmentation. Although not exclusive to the female branch of the Franciscans, the Colettine reforms had a particular impact in the Clarissan communities, awakening a call to reform that would expand beyond the conventual Franciscans. This was especially true in the case of Portugal, where Colettine communities flourished under Observant jurisdiction from the late fifteenth century onwards. In this article I show that, despite their creation under Observant jurisdiction at a time when the Observants were growing in power and number, the first Portuguese Colettines embraced and promoted an identity centred not only in the recovery of Saint Clare’s (1194–1253) experience in Assisi, but also in the figure and sanctity of Colette of Corbie, while searching for authority as part of the Franciscan community. As will be developed, this is particularly evident in the efforts to compile a normative textual support based on the texts revitalised and composed by Colette of Corbie – which would circulate among the Portuguese Colettine convents – and also in the characteristics of these communities’ first artworks.

With or without the Observants? Colette’s reform from Burgundy to Portugal

Before dedicating herself to reforming the Franciscans, Colette experienced a period of religious experimentation, culminating in her joining an anchorhold,Footnote3 where she became a recluse in 1402. Colette’s reform endeavours benefited from the direction and influential connections of two important Franciscan figures during her time as a recluse – Jean Pinet, and Henry de Baume (d. 1439) – who were sympathetic to a reform without dividing the order.Footnote4 Through these connections Colette was granted authorisation to leave her life of reclusion and pursue her plans to reform the Franciscans. This course of action was made possible through an audience with the Avignon Pope Benedict XIII (r. 1394–1417), before whom she professed as a Clarissan nun. She was then granted permission to start her own Clarissan convent in the Amiens diocese.Footnote5 Following Colette’s wish, this convent was granted permission to adhere to the rule written by Clare of Assisi, approved in 1253 by Pope Innocent IV (r. 1243–1254) (known as the First Rule of Saint Clare or Regula Prima), at a time when the great majority of the Clarisses followed the less austere rule issued by Urban IV (r. 1261–1264) ten years later, known as the Urbanist Rule.Footnote6 Following some challenges, which prevented Colette from founding her first convent in Picardy, she finally managed to found her first house in 1410 in Burgundy, at Besançon. Under the patronage of the local nobility, Colettine foundations grew in Burgundy, extending to Savoy and the Southern Low Countries.Footnote7

The establishment of these reformed Clarissan houses at a time when there were no reformed male houses in the region presented a problem for the nuns, who had no friars to take on their pastoral care. This led Colette to extend her reforms to nearby male houses – the Coletans – which were reformed according to the Colettine ideals in order to solve the problem.Footnote8 As noted by Ludovic Vilallet, by extending her reforms to the male branch of the order, Colette ensured her independence from the Observants, as she had her own reformed friars to lean on.Footnote9 However, as the Observants gained strength in France after the Council of Constance 1414–1418, which heavily favoured them, these friars started claiming the order’s reform for themselves and trying to submit the Colettines to their jurisdiction.Footnote10 This was facilitated by a bull issued by Eugenius IV (r. 1431–1447) in 1446. In granting the Observants jurisdiction over the Coletans and thus leaving the nuns with no choice but to be under the Observants’ care, this favoured a gradual transition of obedience to the Observants despite the nuns’ high levels of resistance.Footnote11 The transition was concluded when, in 1517, Pope Leo X officially divided the order, placing the Colettines under Observant jurisdiction.

Under the Observants’ wing: the Colettines in the Iberian Peninsula

New Colettine foundations continued to be created after Colette’s death in 1447 in France and the southern Low Countries, soon reaching the Iberian Peninsula around 1458. The reform entered the peninsula through southern France, with the deployment of nuns from the convent of Lesignan to a new Colettine house in Gandía, Valencia, around this same year. By this time, the first steps towards Clarissan reform had already been taken in Spain. The Colettine house of Gandía had been preceded by a first foundation of reformed Urbanist Clares in 1423, connected to the reformist Tordesillas Congregation. Under the patronage of Queen Maria de Aragón (r. 1420–1445) these nuns were transferred to a new foundation in Valencia in 1445.Footnote12 From the convent of Gandía the reform expanded to other parts of Spain and to Portugal. Despite remaining under conventual jurisdiction, the Colettines of Gandía were faced with a decreasing number of conventual Franciscans in Spain, leaving them without spiritual and temporal support, as the Observants refused to assume the pastoral care of nuns who were not under their jurisdiction.Footnote13 Unwilling to integrate with the Observants, the sisters turned to Rome in 1479, asking for the right to be assisted by Franciscan friars, as predicted by the First Rule of Saint Clare and the Colettine Constitutions.Footnote14 Sixtus IV (r. 1471–1484) granted the nuns’ request, issuing a bull that obliged the Observants to provide support to the convent and declaring that, if the friars failed to confirm the nuns’ election of confessor, their election would be confirmed ipso facto after three days.Footnote15 The bull also granted the convent all the privileges and indulgences of their mother-house, reaffirming its connection to the French Colettines. As shown through the nuns’ petition to Rome, which mentions that both the community’s abbess and vicar came from the mother-house in Lesignan, the convent remained under the direction of the founding group of French nuns until the early sixteenth century.

The Colettines in Portugal: reforming under the First Rule of Saint Clare

Under the governance of the last French abbess, Antónia (d. 1507), a group of seven nuns was sent to Setúbal, not far from Lisbon, to start the Convent of Jesus, the first Colettine house in Portuguese territory. Behind the foundation was Justa Rodrigues Pereira (d. c. 1528), a lady in the household of the Duchess of Beja and Viseu, who, supported by the monarchy, created the conditions to found this first Colettine convent in Portugal from 1489 to 1496.Footnote16 According to the convent’s foundational bull, issued in 1489, Pope Innocent VIII (r. 1484–1492) granted Justa permission to found a convent of nuns of the Order of Saint Clare, under regular observance, with no specific mention of the Colettine houses or their statutes.Footnote17 As will be argued below, Justa’s wish was primarily centred on the foundation of a reformed Clarissan house under the profession of the First Rule, with the connection to the Colettines appearing only in a later phase of the foundation, as a consequence of that first requisite.

The Observants’ popularity in Portugal probably lay behind Justa’s wish as, by the time this foundation occurred, the Observant movement was already well established in the territory.Footnote18 As studied by Maria de Lurdes Rosa, in the context of the Devotio Moderna, Portuguese noble patrons became increasingly involved in the quest for a pious life and more demanding of those responsible for the care of their souls, asking for the observance of religious rules and thus favouring reformed religious houses.Footnote19 Benefiting from the support of the monarchy and nobility, several mendicant houses were founded or reformed in Portugal according to the precepts of Observance from the early fifteenth century onwards. In this context the first attempt to reform the Portuguese Clarisses, led by Beatriz of Portugal (1430–1506), Duchess of Beja and Viseu, came about in the mid-fifteenth century, with the foundation of the observant Convent of the Immaculate Conception in Beja (1459–1482). Beatriz tried, without success, to make this the first Portuguese community to profess the First Rule of Saint Clare.Footnote20 However, the hurdles presented by imposing such a harsh life on noble women led the duchess to ask for a new bull of foundation in 1469, enabling the convent to profess the more permissive Urbanist Rule instead.Footnote21 Thus, in the case of Portugal, the first attempt to use the First Rule in a Clarissan house was arguably not connected to the Colettine movement itself, but to Observance. Besides being recovered by Colette of Corbie in France, this text, with a limited circulation until the fifteenth century, was also revitalised by the Observants in Italy.Footnote22 Here, Clarissan reform flourished under these friars’ wing from 1420 onwards, with Giovanni Capistrano (1386–1456) encouraging the adoption of this normative text in Observant nunneries.Footnote23

It is not clear how the Duchess of Beja and Viseu became interested in the First Rule given that, until the late fifteenth century, all Portuguese Clarisses professed the Urbanist Rule.Footnote24 However, as Rosa has noted, the Duchess was a pious, well-instructed woman, connected to the tendencies of her time, as seen through details such as her convent’s dedication to the Immaculate Conception, whose legitimacy was still debated at the time, or through the rich library with which she equipped not only this convent but also others in Beja.Footnote25 It is thus possible that the duchess was aware of the Italian Observants’ revitalisation of the First Rule. A connection to the Colettine movement should also not be dismissed as the source of Beatriz’s devotion to this rule as her aunt, Isabella of Portugal (1397–1471), who was duchess of Burgundy from 1430 to 1471, was a patron of the Colettines in that territory.Footnote26

Duchess Beatriz’s failed aspiration was probably behind Justa’s wish to found a house of the First Rule in Setúbal decades later – as mentioned, she was part of the duchess’s household and nursemaid to her son, the future King Manuel I (r. 1495–1521). Sousa places the choice of the First Rule for Setúbal after 1492 when Queen Leonor de Lencastre (1458–1525), together with her husband, King João II (1455–1495), started to actively support the convent’s edification, understanding it as a consequence of the queen’s involvement in the foundation.Footnote27 However, a testimonial letter describing the convent’s first stone-laying ceremony, requested by Justa Rodrigues Pereira of the Prior major of Palmela in 1490, mentions the creation of a convent for nuns of the First Rule of Saint Clare, by the foundress’s wish.Footnote28 Similarly, in the chronicle narrating the convent’s history, the nun Leonor de São João states that the foundress, wishing to establish a convent of the First Rule of Saint Clare, worked to obtain the necessary papal permission in 1489.Footnote29 Thus, the profession of the First Rule was arguably part of the foundress’s original plans rather than simply a consequence of the queen’s patronage from 1492 onwards.Footnote30

The connection to the Colettine movement, however, appeared later in the foundation plans, probably dictated by the absence of Portuguese senior nuns professing the First Rule, who were necessary to start the new community. In the face of this absence, the Colettine convents of Gandía and Girona in Spain emerged as the closest source for senior nuns. At the time, they were the only communities professing this rule in the Iberian Peninsula, as narrated in the convent’s chronicle: “the founder decided to go to Gandía in person in order to bring nuns to start the convent, as that was the closest house professing the First Rule of Saint Clare in Hispania.”Footnote31 This hypothesis is supported by the fact that the connection to the Colettines can only be documented as late as 1496 – the official start of claustral life – when a brief issued by Alexander VI (r. 1492–1503) authorised the community to receive nuns from the convent of Gandía.Footnote32 According to the surviving chronicle, Justa Rodrigues Pereira, aided by King Manuel, worked to bring the Valencian nuns to Portugal in May 1496.Footnote33

In addition to authorising the deployment of nuns from Gandía to Setúbal, the brief issued by Alexander VI in 1496 also granted the new convent the same privileges of the former regarding choice of confessor, thus protecting the new convent from the same problems regarding the Observants’ support and meeting the requirements presented by both the Rule of Saint Clare and the Colettine Constitutions, which demanded that the nuns be assisted by Franciscan friars only.Footnote34 This brief was issued in conjunction with another one stating that the convent should be under the Observants’ jurisdiction and that these friars should provide the nuns with a confessor, a chaplain and a lay friar.Footnote35 More than one year after the beginning of claustral life, in December 1497, another brief from the same pope granted the community of Setúbal all the graces, privileges and indulgencies of its mother-house in Gandía, reinforcing the connection of the new religious house to the Colettines despite its foundation within the Observant faction of the Franciscans.Footnote36

The death of Alexander VI in 1503 led Justa Rodrigues Pereira, through King Manuel I, to ask the new pope, Julius II (r. 1503–1513), for confirmation of all the privileges granted by his predecessors. Issued in 1505, the brief was addressed to both Justa and her community, reaffirming not only the convent’s commitment to the First Rule, but also the connection to the Colettines, stating that the convent was never to change its profession as its nuns should forever live under the First Rule of Saint Clare and observe it entirely, “as it was observed in the Convent of Gandía.”Footnote37

As will be discussed next, the texts and artworks commissioned and used in the first Portuguese Colettine convents had an important role not only in the promotion of this commitment to the Colettines and Saint Clare’s Rule, but also on the legitimation and inscription of Colette’s work and this new branch of the Clarisses in Franciscan history. This is particularly evident in the efforts to compile and promote the translation of a set of texts revitalised and composed by Colette of Corbie which, as will be demonstrated, was transmitted to the future Colettine convents founded in Portugal in the sixteenth century.

Embracing a Colettine identity: looking for authority

A textual support: the commissioning and use of normative and para-normative texts in Portuguese Colettine convents

With the aim of reconnecting the Clarisses to the forma vitae experienced by Clare of Assisi in the thirteenth century, Colette of Corbie had worked to revitalise and compose a set of texts to support her reforms. In addition to recovering the First Rule of Saint Clare, with its sense of humility and strict conception of evangelical poverty, Colette also wrote her own set of Constitutions (finalised in the 1430s), meant to complement Clare’s rule.Footnote38 Written with a reformist purpose, Colette’s Constitutions brought clarity to Clare’s rule, emphasising the importance of enclosure and diligent religious practice, and bringing about a more severe view of the topic of obedience.Footnote39 These texts would become the normative set of texts for the Colettines, with their observance being approved by Minister General William of Casale (1390–1442) in 1434 and later confirmed by Pius II (r. 1458–1464) in 1458.Footnote40

The earliest known exemplar of the First Rule in Portugal is written in the vernacular and appears in an codex from the Convent of Jesus in Setúbal; it was arguably made between the last years of the fifteenth century and the first years of the sixteenth.Footnote41 Accompanying the rule are vernacular versions of other texts connected to the way of life initiated by Saint Clare in Assisi, which are also the first known exemplars in Portugal: her spiritual testament and the blessing she gave to her sisters (composed in the early 1250s), and the Privilege of Poverty (1216) – a papal privilege ensuring the community’s right not to own communal property and thus ensuring the maintenance of Franciscan evangelical poverty.Footnote42 Despite not officially recognised as normative documents, these texts, seen as testimonies of the way of life led by the community of Saint Damian, complement Saint Clare’s rule, assuming a para-normative function.Footnote43 Besides registering Saint Clare’s view on how her sisters should live, they also testified to their connection to Saint Francis – who, as registered by Clare, gave them the forma vitae that inspired her rule – along with his commitment to take care of them.Footnote44

The presence of such texts in Setúbal from the community’s early years is testimony to the nuns’ commitment to the way of life prescribed by the First Rule. The degree of this commitment can be seen through the nuns’ concern with having these texts translated into Portuguese, which would have facilitated their comprehension by non-Latinised nuns. It is important to note that normative texts were to be read out loud frequently for the gathered community in Colettine houses, as can be seen in their Constitutions, which recommend that a vernacular version of this text be read clearly in the refectory at least six times a year.Footnote45 Setúbal’s codex was still used in the convent into the early nineteenth century, as revealed by a note from 1832 mentioning that this rule was to be used by the abbess and returned to Father Heitor (probably the convent’s chaplain at the time) by the end of the abbacy.Footnote46 As Gomes has noted, this suggests a tradition of passing the codex from one abbess to the next.Footnote47 This shows the importance of this particular exemplar within the community, also reflected in its rich pen-filigreed decorations that contrast with the bareness of other surviving exemplars. As stated in the Colettine Constitutions and recorded in the convent’s chronicle, the novices should profess their vows to the abbess in manibus (placing their hands inside the abbess’s hands) over the text of the First Rule of Saint Clare.Footnote48 The abbess’s volume might have been the book used on these occasions.

The recovery of Saint Clare’s writings and other texts associated with her experience in the proto-monastery of Saint Damian in Assisi, brought about in the fifteenth century as a consequence of the renewed interest of both the Colettines and the Observants in reforming the Clarisses, was commonly accompanied by its vernacular translations. Several codices containing some of these texts in the vernacular were produced in and for reformed convents of Clarisses in the fifteenth, sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, as is apparent in the surviving exemplars in Portugal, Italy and Spain.Footnote49 In the case of Portugal, the circulation of these texts was arguably both initiated in and circumscribed to Colettine convents, as Portuguese Observant Clarisses kept the Urbanist Rule.Footnote50 Thus, the nuns that came from the Convent of Santa Clara in Gandía to found the Colettine convent of Setúbal in 1496 might have been responsible for the introduction of these texts in Portugal, as they were essential not only to introduce the new nuns to the way of life practised in the mother-house, but also to guide the community in its daily life. Coleta Talhada (d.1560), a Valencian nun who came from Gandía to be Setúbal’s first abbess (r. 1496–1508), commissioned two codices with similar content for the convent of Madre de Deus in Lisbon, which she directed as abbess from 1509 to 1560.Footnote51 Despite the absence of evidence connecting this abbess to Setúbal’s codex, it is possible that she was behind its commission before departing to Lisbon as, according to Gomes, the book was made during the period she was Setúbal’s abbess (1496–1508).Footnote52

It is difficult to know if the sources used in these texts’ translation came directly from the convent of Gandía as no exemplars, either in Latin or the vernacular, are found originating from this community. However, it was possible to learn that Castilian versions of these texts circulated in Spain in the first half of the sixteenth century, as demonstrated by the content of a surviving codex of unknown provenance, today located in Burgos, Spain.Footnote53 This book was probably used by a Colettine nun, revealed in the presence of the sister’s name, “Ana,” in the profession formula integrating the Colettine Constitutions.Footnote54 However, despite their similar contents, the two codices are not likely to have come from the same source, as is evident in some slight differences. In contrast to what happens in the codex from Burgos, the vernacular version of the First Rule presented in the book from Setúbal is not in accordance with the Latin text recorded in the original bull kept in the proto-monastery of Saint Damian in Assisi.Footnote55 Both texts differ slightly in their contents.Footnote56 In addition, unlike the Portuguese codex, the book from Burgos does not include Saint Clare’s blessing. Even so, in both codices, the vernacularisations of the Privilege of Poverty and Saint Clare’s Testament appear to have come from the same Latin sources.Footnote57 These variations suggest that several sources circulated in Iberia in the sixteenth century.

The codex from Burgos also contains a vernacular version of the Colettine Constitutions – a text that is absent from the Portuguese volume. Despite the fact that the first known copy of the Constitutions, from Setúbal’s convent, dates from 1560, these statutes were arguably followed by the nuns since the beginning.Footnote58 Sister Ana do Amor Divino wrote in her eighteenth-century chronicle that the convent’s first abbesses, who came from Gandía, put a great deal of effort into full observance of the First Rule of Saint Clare and the Colettine Constitutions.Footnote59 Moreover, as stated in the above-mentioned papal decrees, the community was to be modelled on the way of life observed in the mother-house, the adherence of which to the Colettine Constitutions is documented. In 1472, Cardinal Rodrigo Borja wrote in the prologue, preceding his confirmation of the Colettine Constitutions with additions by Minister General Jaime Zarzuela (1458), that he was doing so at the request of the community of Santa Clara of Gandía who, like their mother-house in Lesignan, followed the Colettine statutes.Footnote60 It is therefore likely that, despite its absence in the two earlier codices, the text of the Colettine Constitutions was also used in Setúbal in the first half of the sixteenth century. It is important to reiterate that these statutes should be read in the vernacular at least six times a year for the gathered community and also during visitations, which would be difficult to do without access to the written text.Footnote61 As noted, in 1509, Setúbal’s first abbess, Coleta Talhada, was transferred, along with a group of nuns, to the new Colettine convent of Madre de Deus in Lisbon, the second of its kind in Portugal. The fact that she commissioned a codex containing the Colettine Constitutions for her new convent in 1523 also shows that the Portuguese Colettines were bound to these statutes from their earliest years.Footnote62

Thus, the codex commissioned by Abbess Coleta Talhada for Madre de Deus in 1523 contains the earliest exemplar of the Colettine Constitutions known in Portugal until today. The text is preceded, in a similar fashion to the above analysed codices, by vernacular versions of the First Rule, the Privilege of Poverty and Saint Clare’s Testament and Blessing, which are then followed by a second part, compiling the Latin versions of these texts, and two papal bulls.Footnote63 The codex’s colophon informs us that it was written by Friar Diogo de Leiria for Abbess Coleta Talhada in 1523. The Constitutions were translated from Latin by the friar, as he himself attested in the prologue preceding the translation. However, contrary to expectation, the text translated is not the version used in Gandía, which contained the additions made by Minister General Jaime Zarzuela in 1458, as Cardinal Borja’s confirmation shows, but the earlier version of the Constitutions, as approved by Minister General William of Casale in 1434. As the Cardinal noted in the prologue preceding his confirmation of the Constitutions for the nuns of Gandía, these statutes, in the version declared by Zarzuela and approved in the General Chapter of Rome in 1458, were used in this convent from its foundation.Footnote64 Does this mean that, in contrast to what happened in the mother-house, the Portuguese Colettines followed the early version of the Constitutions? This is unlikely, as the codex copied by Friar António de Tomar for the Convent of Setúbal in 1560 contains the Portuguese translation of the version used in Gandía, proving that, at least by this period, the nuns were in agreement with the mother-house. In addition, two codices used in the convent of Madre de Deus of Lisbon – dating from the second half of the sixteenth century and from the early seventeenth century, respectively, also show this version.Footnote65 Zarzuela’s version can also be found in a codex copied by the first abbess of the Convent of Assunção in Faro, Inês d’Ascenção (r. 1541–1566), between 1541 and 1566.Footnote66 As with Madre de Deus, this convent was founded by the now Queen Dowager Leonor de Lencastre and started by a group of nuns from the first house (including the abbess Inês d’Ascenção herself), suggesting that this version of the Constitutions might have been used in Madre de Deus in the first half of the sixteenth century. Similarly, a sixteenth-century codex from an unknown provenance, also containing Saint Clare’s texts followed by Zarzuela’s version of the Colettine Constitutions in the vernacular, bears an ownership mark connecting it to a nun who professed in Madre de Deus and was later deployed to the new Convent of Mártires in Santarém in 1581.Footnote67 Finally, this version is also present in a codex from the National Library of Portugal, the provenance of which is unknown.Footnote68 This book bears exactly the same versions of the texts copied by Inês d’Ascensão in Faro in the mid sixteenth century,Footnote69 suggesting a common source for both that, as developed when addressing the codex of Faro, might have been used in the convent of Madre de Deus in an earlier period. An analysis of codicological and palaeographical aspects places both codices in the same chronological period. Thus, Zarzuela’s version was arguably the predominant text in the Portuguese Colettine convents from the early sixteenth century and, to date, the codex commissioned by Abbess Coleta Talhada to Friar Diogo de Leiria for Madre de Deus in 1523 contains the only known exemplar of the early version of the Constitutions in Portugal, both in Latin and in the vernacular. Despite not being used in Gandía, the text as approved by Casale also circulated in early-sixteenth-century Spain, as it is the version contained in the Castilian codex from Burgos discussed above. However, the presence of Zarzuela’s version in a copy made for the Convent of Jerusalén of Valencia in 1525 suggests that these were the statutes followed in the communities derived from Gandía.Footnote70 The presence of seventeenth-century editions of Zarzuela’s version in several Colettine convents in Spain suggests that this was the prevalent version in this territory. Footnote71

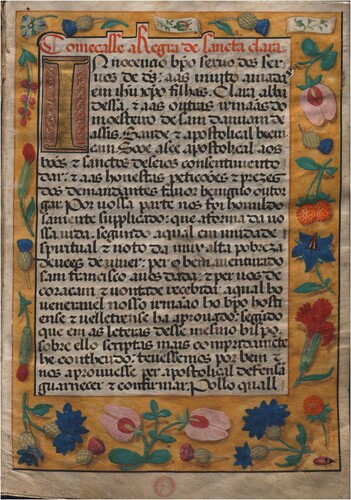

The Constitutions copied and translated into the vernacular by Friar Diogo appear as an isolated case among the surviving samples of this text in Portugal. On the basis of the information currently available, it is difficult to identify the reason behind the commissioning of this version of the text by Coleta Talhada, but further analysis of the codex containing it might reveal some clues. In contrast to the other Portuguese codices, this volume is complemented, in a second part, with the Latin versions of the texts presented in the first. This is followed by a 1298 confirmation of the bull Quasdam Litteras (1296) and the bull Licet Romanus Pontifex (1439), decrees that helped in defining the position of the Clarisses as part of the Franciscan family, extending the privileges received by the Friars Minor to these nuns and putting them under the direct jurisdiction of the Franciscans. The presence of these decrees alongside the Latin version of the texts that regulated the Colettine way of life gives the codex an increased juridical and historical tone that is absent from other analysed volumes.Footnote72 Thus, it is plausible that the nuns would have wanted to include the original version of the Constitutions in such a codex, despite following Zarzuela’s version. In addition, the lavishly illuminated folio that opens the codex and the elegant pen-filigree work decorating the initials throughout indicate that this was an expensive volume (). These exceptional characteristics might be a sign that this volume was not intended to be used and carried by the nuns on a daily basis. Instead, this might have been a book with ceremonial functions representing a monument of the Colettines’ history and authority, used, for instance, during the nuns’ profession.Footnote73 Similarly to what happened in Setúbal, where a lavishly decorated volume of the Rule was transmitted from abbess to abbess, this could have been the exemplar used by the abbesses of Madre de Deus.

Figure 1. First Rule of Saint Claire (Opening folio), Diogo de Leiria, Rule of Saint Clare, 1523. Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal, Il. 208, fol. 1r. Photo: Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal.

It is important to note, however, that no major differences separated Zarzuela’s version of the Constitutions from the original text approved in 1434, which enabled both texts to co-exist in these nunneries. Most of Zarzuela’s additions complement the information offered by Colette as is apparent, for instance, in the inclusion of the instructions for the ceremony of ProfessionFootnote74 or the procedures for the development of visitations.Footnote75 The General’s additions are also used to deepen the link between the Clares and the Franciscans in the chapter regarding the convent’s confessors. If the original version states only that, as mentioned in the Rule, the Clares should have confessors from the Friars Minor,Footnote76 Zarzuela’s text provides a further development to this information, complementing it with the words of Saint Francis recorded by Saint Clare in the sixth chapter of her Rule, where he promises that he and his friars should always take care of Saint Damian of Assisi’s sisters.Footnote77

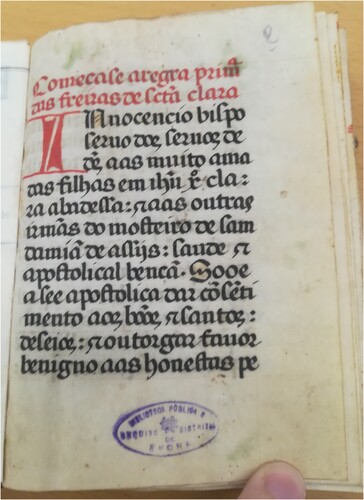

As noted, during her time in Madre de Deus, Abbess Coleta Talhada was responsible for the commissioning of at least one more codex, as recorded in the book’s colophon.Footnote78 As with the analysed books, this volume is devoted to compiling the First Rule of Saint Clare, the Privilege of Poverty and Saint Clare’s Testament and Blessing. However, as with the two earlier volumes from Setúbal, this codex also lacks the Colettine Constitutions. Although undated, the volume is signed by the Franciscan friar António de Tomar (1506– c.1600), who was born in 1506.Footnote79 According to the chronicler Jerónimo de Belém, he died around 1600.Footnote80 This indicates that this book was almost certainly posterior to the codex containing the Constitutions made at the abbess’s request in 1523 by Friar Diogo de Leiria, when António de Tomar was only seventeen years old. Moreover, a few records show Toledo’s involvement with the Clarisses in a later chronology. He was confessor in the Convent of Jesus of Setúbal in 1560, a charge that he held again in 1571 and 1583.Footnote81 Records in this later chronology also show him writing rules for the Clarisses, revealed in the colophons of books he made for these nuns in 1560 and 1575.Footnote82 By the time Friar António’s book was produced, the nuns of Madre de Deus were already in possession of at least the early version of the Constitutions, suggesting that the absence of this text in the book was a deliberate choice.Footnote83 However, the reason behind this choice is not clear. These legislative codices, despite following a generally similar structure, appear to have had distinct functions according to their specific characteristics, which could explain such variations. For instance, Friar António’s book was a modest and small volume, which would be easy for the nuns to carry around, while Friar Diogo’s, as shown, was not only larger, but a lavish and more expensive book ().Footnote84 A characteristic of Friar António’s codex indicates that it might have been used for private devotional practice or study purposes, rather than ceremonies or mandatory readings of normative texts in communal gatherings. The commentaries written by Friar António in the margins of the text of the First Rule clarify this, dividing it into precepts, admonitions, liberties and conditions.Footnote85 Similar-sized surviving volumes bear ownership marks indicating that they belonged to or were used by specific nuns.Footnote86 One of these volumes, used by a nun who professed in the convent of Madre de Deus before 1581, although containing the Colettine Constitutions, repeats the marginal comments made by Friar António in his book.Footnote87 It is possible that the codex made by Friar António de Tomar was used in the instruction of novices who needed to understand the meaning behind the words of the rule they were about to profess. However, other reasons might have been behind the absence of the Constitutions in some of these volumes, as the second codex from Setúbal – finished in 1531, after Friar Diogo’s translation of the Constitutions – also lacks these statutes; despite being a small, modest volume, it does not contain any comments.Footnote88 As mentioned, the Madre de Deus community was started with nuns from Setúbal, and both convents shared the same graces and privileges originally granted to the convents of Lesignan and Gandía. They were also both under the protection of Queen Dowager Leonor de Lencastre who, as discussed below, was behind some shared pictorial traditions in both convents. It is therefore natural to assume that the lack of the Constitutions in Setúbal’s second codex of 1531 was also not because of a lack of access to this text.

Figure 2. First Rule of Saint Claire (Opening folio), António de Tomar, Rule of Saint Clare, sixteenth century. Biblioteca Pública de Évora, Cod. CXIII/1–43, fol. 1r. Photo: author.

The efforts to revive Clare’s forma vitae also resulted in a Portuguese translation of Thomas of Celano’s Life of Saint Clare (1255–1261), made in 1526 for the convent of Madre de Deus.Footnote89 Unlike an earlier and briefer version that can be found in the 1513 Portuguese translation of the additions to the Castilian Flos Santorum (1500), the new extended translation included some previously avoided aspects such as the concession of the Privilege of Poverty and the approval of Saint Clare’s own rule, cornerstones of Colettine reform.Footnote90

Images of the founder: portraying authority through Colette’s sanctity

Attempts to canonise Colette of Corbie started soon after her death in 1447. Seeking recognition of her work and legitimisation of her reforms, the Colettines started to gather all the necessary information to seek the canonisation of their foundress, and her first hagiography, written by her confessor Pierre de Vaux, was finished by 1448.Footnote91 Although the process was initiated as soon as 1461, under the patronage of Philip the Good (1396–1467), Colette’s canonisation faced several hurdles that delayed its conclusion until 1807.Footnote92 As Campbell has shown, from the Reformation and Counter Reformation of the Church, which influenced views of sanctity, to the lack of Franciscan interest in promoting a figure such as Colette, several factors contributed to delaying this process.Footnote93 This also delayed the authorisation of Colette’s cult, which happened only in the early seventeenth century (1604–1635), and, consequently, the development and dissemination of her iconography. Although pictorial representations of Colette were already being developed in the southern Low Countries in the second half of the fifteenth century, as can be seen in the two illuminated versions of Pierre de Vaux’s Vie de Soeur Colette, made between 1460 and 1477 at the Burgundian Court, not many are known today.Footnote94 The same appears to be true for the period after the authorisation of her cult in the early seventeenth century.Footnote95 This reveals the exceptional character of Setúbal’s panel, which, as will be shown, arguably had its origin in the Low Countries, where the Colettines had a stronger presence and, as noted, representations of Colette were already being developed. As well as an early representation of Colette, Setúbal’s panel can also be placed among the first known artworks to depict her as a saint, as confirmed by the inscription in her halo: “Sca Coleta.”Footnote96 As will be demonstrated, along with the analysed texts with which they were contemporary, images played an important role in these communities’ adoption and affirmation of a Colettine identity and in their search for authority within the Franciscan family.

The first of these paintings comes from the Convent of Jesus of Setúbal and pictures Colette of Corbie as a haloed abbess being crowned by an angel, alongside Saint Agnes and Saint Clare of Assisi (). It is not clear when the panel entered the convent. However, the convent’s chronicle states that the church’s high altar was decorated around 1500 with paintings given by King Manuel, used in conjunction with artworks previously donated by his sister, Queen Dowager Leonor de Lencastre, to form an altarpiece. The chronicler underlines the beauty of the paintings, saying that they came to Portugal through the monarchs’ cousin, Maximilian I of Habsburg (1459–1519).Footnote97 It is thus possible that this painting, attributed by Luís Reis Santos to the Flemish painter Quentin Metsys (1466–1530), might have been among the paintings sent by Maximilian and offered by the monarchs on this occasion.Footnote98 Besides being depicted as a saint, in this panel Colette is also placed alongside the two founding figures of the forma vita initiated in Saint Damian, conveying an idea of continuity and thus legitimising Colette as the restorer of that way of life.

Figure 3. Apparition of an Angel to Saint Claire, Saint Agnes and Saint Colette, attributed to Quentin de Metsys, c. 1491–1507. Photo: Museu de Setúbal/Convento de Jesus.

Given the information provided by the chronicle, this painting might have been among the first group of artworks used to decorate the church’s high altar. This was not only one of the most prestigious places in the monastic building but also a place that could be seen by the laity, on whose alms the nuns’ mendicant way of life depended. According to the chronicle, the group of paintings used to decorate the church’s high altar included Passion scenes and the saints of the Order. Placing such a painting for viewing alongside prominent Franciscan figures legitimised Colette’s sanctity and consequently her work as reformer and founder of the Colettines, a still barely known branch of the Clarisses in Portugal. The fact that the same theme was repeated with few alterations in a new altarpiece destined for the church’s high altar, made some years later (c. 1517–1530) and arguably commissioned by the queen dowager from the Portuguese painter Jorge Afonso, strengthens the hypothesis that the first panel was part of the first altarpiece, demonstrating the intention of placing this scene in this prestigious and highly visible place ().Footnote99 In addition, in the new altarpiece, the panel was accompanied by other paintings picturing the main figures of the Franciscan order (Saint Daniel and his Companions, Saint Francis, Saint Anthony, Saint Bonaventure and Saint Bernardino of Siena), confirming the intention of placing Colette among the most important figures of the Franciscan family. This is reinforced by the fact that, in the new panel, Colette is given a more prestigious position, changing places with Agnes and thus appearing closer to Clare. The extent of the effort to promote the Colettines through the affirmation of Colette’s sanctity can be seen by the fact that this theme was also transmitted to the new Colettine house of Madre de Deus founded by the queen dowager in Lisbon in 1509, as attested by a surviving panel made circa 1510–1520 ().Footnote100 As with the two previous paintings, in this scene, the haloed Colette is identified with the inscription “S. Colleta.”

Figure 4. Apparition of an Angel to Saint Claire, Saint Agnes and Saint Colette, attributed to Jorge Afonso, c. 1517–1530. Photo: Museu de Setúbal/Convento de Jesus.

Figure 5. Apparition of an Angel to Saint Claire, Saint Agnes and Saint Colette, artist unknown, c. 1510–1520. Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga. Photo: José Pessoa. Direção-Geral do Património Cultural/Arquivo de Documentação Fotográfica.

This theme initiated an early tradition of depicting Colette as a saint in Portugal, long before her canonisation in 1807, as further confirmed by a panel depicting Saint Colette commissioned for the doors of the upper choir grille of the Convent of Jesus of Setúbal by the abbess Eufrásia de Santa Catarina in 1611.Footnote101 The tradition went beyond the Colettine convents, as seen in the seventeenth-century depiction of Saint Colette holding a cross – attested by the label “S. Coleta” – in one of the panels decorating the Chapel of Saint John the Baptist in the convent of urbanist Clarisses of Chagas in Lamego.Footnote102 Early depictions of Colette are hard to find in other Iberian convents. A seventeenth-century panel from the Convent of Santa Clara in Gandía, depicting Colette as an abbess and saint, bears some resemblance to Setúbal’s theme as, despite being represented alone she is, once again, being crowned by an angel.Footnote103 However, in this case, the halo and the inscription “S.ta Coleta” were added in the nineteenth century, which suggests that depictions of Colette as a saint were not common in Gandía, the Iberian Colettines’ mother-house, until her canonisation in 1807.Footnote104 Even so, a representation of Saint Colette can be found in the Convent of Anunciación in Valladolid in a painting made in 1610 by the Florentine Niccolò Betti (c. 1550–1617). Although this painting was probably one of several Florentine artworks that entered the convent through the patronage of Margarita de Austria (1584–1611),Footnote105 the choice to depict Colette as a saint might have been influenced by the presence in the convent of Portuguese nuns who came from Madre de Deus of Lisbon to found it in 1550.Footnote106

The early tradition of depicting Colette as a saint in Portugal may have been imported from central Europe through the Portuguese monarchs’ connection to Maximilian I of Habsburg through whom, as noted above, they may have obtained Setúbal’s first panel. Although similar representations outside Portugal are not known, representations of Colette as a saint might have been developed along with the first manifestations of her cult in places with a strong Colettine presence. After her death in the convent of Ghent in 1447, Colette’s cult rapidly developed in this city under the support of Philip the Good and Charles the Bold (1433–1477).Footnote107 Furthermore, despite the nun’s cult first being authorised in 1604 to the convent of Ghent by Clement VIII, Jean Molan’s sixteenth-century martyrology registers that a mass in honour of Colette was celebrated in this convent on the anniversary of her death (6 March).Footnote108 The same appears to have happened in Bensançon, Burgundy, where the first Colettine convent was founded by Colette in 1410: according to testimony collected among the citizens in 1629 as part of Colette’s canonisation process, a resident claimed to have seen and honoured ancient images representing Colette crowned with the saints’ halo. He noted that, during Colette’s feast, celebrated on 6 March, images of the nun were also distributed to people who greatly reverenced them.Footnote109

It is not possible to confirm if the devotion shown to Colette through the use of imagery had parallels in the early development of her cult in the first Colettine communities of Portugal. However, a sixteenth-century Castilian translation of Colette’s life (c. 1557–1570) made by Friar Marcos de Lisboa (1511–1591) for the nuns of Nuestra Señora de la Consolación in Madrid testifies to the cult of Colette in Iberia before its authorisation by the Holy See; the volume ends with texts for the Commemoratio devotissimae Virginis Collectae.Footnote110 Friar Marcos – confessor in the convent of Madrid – revealed in his prologue that he decided to offer a copy of Colette’s life to the community’s abbess, Juana de la Cruz (1535–1601), after becoming familiar with the text in his work to collect information for the third part of his Cronicas de la Orden de los Frayles Menores (1570). According to the friar, the text was translated from Catalan, showing that this vita, originally composed by Perrine de Baume (b. 1408) around 1477, and probably the texts used in the Commemoratio, was already circulating before the late sixteenth century in the Catalan-speaking regions of Iberia, where the first Colettine communities were founded.Footnote111 These texts arguably did not circulate in Portugal before this period, as a letter written by the bibliophile Jorge Cardoso (1606–1669) to Friar Francisco Haroldo mentions the existence of a manuscript of the Life of Sister Colette (Vida de Sor Coleta), translated into Portuguese by Friar Marcos de Lisboa, suggesting that the friar was also responsible for introducing the text into Portugal.Footnote112

Final remarks

The complex context in which the first Portuguese Colettine convents were founded might have been behind the need felt by these communities to affirm not only Colette’s sanctity but also her prominent place in Franciscan history during their early years. As shown in the first part of this study, by the time the first Colettine convent was founded in Portugal, Clarissan reform was far from being a reality in this territory. In addition, religious life under the First Rule was still viewed with suspicion, as shown through the Convent of Immaculate Conception where its failed implementation met several hurdles a few years earlier. Thus, as well as being the second house of reformed Clarisses in Portugal, the nuns from the Convent of Setúbal were also the first community to adopt the harsh Rule of Saint Clare in this territory. Furthermore, they represented a new reformed branch of the Clarisses with a rare representation in Iberia, traditionally associated with the Conventuals, a branch of the Franciscans overshadowed in Portugal by the popularity of the Observants, upon whom they depended. The efforts of the first Portuguese Colettines to compile and translate the texts revitalised and composed by Colette of Corbie, which became the set of normative and para-normative texts of the Colettine communities, shows these nuns’ commitment not only to embrace the First Rule but also to adopt a specifically Colettine identity. As demonstrated by the efforts made to stress these nuns’ connections to the Franciscans, seen through the nuns’ request for papal decrees enforcing it, the inclusion of historical pieces of legislation regarding this matter in codices of normative texts shows that these communities also used such volumes to affirm their belonging to the Franciscan order. This effort was accompanied by the commission of artworks, the themes of which placed the founder of their branch – Colette of Corbie – among the most prominent figures of the Franciscan order as a legitimate follower of Clare of Assisi. In addition to working on their internal identity shaping, apparent in the commissioning of vernacular versions of the texts that defined the Colettine movement, these nuns were also concerned with legitimatising their branch outside their enclosed spaces, as made visible in the ways in which they chose to promote and use Colette’s sanctity through imagery.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Paula Cardoso

Paula Cardoso holds a PhD in Art History from the Nova University of Lisbon (2019). Her thesis focused on the role of Portuguese Dominican nuns in the production and patronage of illuminated liturgical books for their convents in the context of Observance. From 2021 to 2023 she was a Marie Skłodowska-Curie IF Postdoctoral Fellow at University Pompeu Fabra – Barcelona; currently she works at the Instituto de Estudos Medievais of the Nova University of Lisbon, where she was granted a research contract under the FCT program Scientific Employment Stimulus (CEEC). She is developing a project focused on the intersections between visual and literary cultures of mendicant nuns and their religious praxis in late medieval Portugal.

Notes

1 For a general overview of the Observant reforms, see Mixon and Roest, A Companion to Observant Reform.

2 In order to be distinguished from the Observants, non-reformed branches of religious orders started to be referred as “Conventuals” in the fifteenth century, when the term became associated with those who lived aside from their religious vows.

3 An anchorhold is a small place of reclusion, often associated with a church. The recluse, known as an anchorite, lived permanently enclosed in this space and was considered dead to the earthly world.

4 Campbell, “St Colette of Corbie and the Friars ‘of the Bull’,” 46.

5 This might have been favoured because Benedict XIII had a tendency to reform the Clarisses as he had previously shown by enabling the Avignon minister general to promote rigour among these nuns (Roest, Order and Disorder, 171).

6 Campbell, “St Colette of Corbie and the Friars ‘of the Bull’,” 46. These were not the only two rules followed by the Clarisses, which were far from having legislative uniformity, see Roest, “Rules, Customs, and Constitutions.”

7 Sommé, “The Dukes and Duchesses of Burgundy,” 32–55.

8 Viallet, Colette of Corbie and the Franciscan Reforms, 90–99.

9 Viallet, Colette of Corbie and the Franciscan Reforms, 81.

10 Richards, “The Conflict between Observant and Conventual.”

11 On the meaning of this bull for the Coletans, see Campbell, “St Colette of Corbie and the Friars ‘of the Bull’,” 60–64.

12 Amorós, “El monasterio de Santa Clara de Gandía,” 451–63.

13 Amorós, “El monasterio de Santa Clara de Gandía,” 480.

14 According to Amorós, “El monasterio de Santa Clara de Gandía,” 480–81, the draft for this petition, redacted in Valencian, survives in the Convent of Santa Clara in Gandía.

15 Pou y Martí, Bullarium Franciscanum, 3:601. The nuns appear to have been facing this problem since the convent’s foundation, as a 1464 document issued by the Vicar General of the Cismontane family, Jaime Zarzuela (r. 1458–1464), had already obliged the Observant friars to assume the nuns’ cura. The document is edited in Ivars, “Origen y propagación de las Clarisas Coletinas,” 100–01.

16 Justa Rodrigues Pereira has recently been discussed in Rodrigues, “Splendour in Life, Humility in Death.”

17 A copy of the bull can be found in Belém, Chronica Serafica, 2:577–78.

18 For an overview of Franciscan Observance in Portugal, see Teixeira, O movimento da observância Franciscana; Rodrigues, Fontes, and Andrade, “La(s) reforma(s) en el franciscanismo portugués.”

19 Rosa, “A religião no século.”

20 All the Clarissan convents founded in Portugal up to the late fifteenth century professed the Urbanist Rule, with the exception of the communities of Lamego and Entre-Ambos-os-Rios, founded before the creation of that text, which followed Cardinal Hugolino’s rule in their early years. See Andrade, “‘Conhece a tua Vocação’,” 85.

21 For more on the creation of this convent and its patron, Beatriz of Portugal, see Rosa, “A fundação do Mosteiro da Conceição de Beja;” Rodrigues, “Splendour in Life, Humility in Death.”

22 Knox, Creating Clare of Assisi, 155. The text was also rare in France at the beginning of the fifteenth century, demonstrated by the fact that Colette of Corbie had to order a copy from Assisi in 1410. See Roest, Order and Disorder, 174.

23 On the reform of Italian Clarissan houses, see Knox, Creating Clare of Assisi, 125–56. Even so, according to Roest, Order and Disorder, 183, not all the Observant Clarissan convents adopted Saint Clare’s rule, with some choosing to diligently observe their previous rules instead.

24 The earliest known version of this text in Portugal was produced between the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries for the Convent of Jesus in Setúbal (Regra de Santa Clara, c. 1496–1508, Arquivo Distrital de Leiria [ADL], CRSC).

25 Rosa, “A fundação do Mosteiro da Conceição de Beja,” 269–70.

26 Sommé, “The Dukes and Duchesses of Burgundy,” 38. Isabella of Portugal is usually presented as the possible connection between the Colettine movement and the Portuguese nobility. See Sousa, A Rainha D. Leonor (1458–1525), 454; Andrade, “Uma espiritualidade renovada,” 164. Sousa suggests that this connection might have been made through Queen Leonor de Lencastre (1458–1525), Beatriz’s daughter, whose future confessor, Diogo Gonçalves (d. 1488), visited Isabella’s court accompanying her nephew, Jaime of Portugal (1443–1459), in the 1450s. Yet it is also plausible that this connection might had happened earlier through Beatriz, Isabella’s niece and Leonor’s mother, on account of her early devotion to the First Rule. Furthermore, as noted by Santa Maria, O ceo aberto na terra , 794–99, Diogo Gonçalves only started working as Leonor’s confessor in the 80s; this weakens Sousa’s hypothesis as a thirty-year gap separates his work with the queen from his visit to Burgundy in the 1450s.

27 Sousa, A Rainha D. Leonor (1458–1525), 474–76. Queen Leonor’s piety and religious patronage has recently been discussed in Rodrigues, “Splendour in Life, Humility in Death.”

28 A copy of the letter can be found in the convent’s chronicle: S. João, Tratado da antiga e curiosa fundação, 1630, Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal (BNP), Cod. 7686, livro 1, cap. II, fol. 25r.

29 S. João, livro 1, cap. II, fol. 23r.

30 Leonor de Lencastre’s role, as will be shown below, was crucial in shaping the convent’s Colettine identity.

31 “(…) determinousse a_nobre fundadora a ir em_pessoa a_buscar freiras para a fundação a Gandía, porque nas Espanhas não havia mais perto outro mosteiro da primeira regra de nossa madre Santa Clara (…).” (S. João, livro 1, cap. V, fol. 10r).

32 Cópia de um Breve de Alexandre VI, seventeenth century, ADL, Dep. VI/25/A/4, n°1.

33 S. João, livro 1, cap. V, fols. 10r–11r.

34 Cópia de um Breve de Alexandre VI. As mentioned, Sixtus IV issued a bull that obliged the Observants to assume the Valencian nuns’ cura.

35 These conditions were met since the beginning, when the convent’s first confessor was the Observant Henrique Soares of Coimbra (S. João, livro 5, cap. XXXI, fol. 226r). The content of these briefs is summarised in a 1636 document from the Colettine convent of Madre de Deus de Lisboa (Sumário das Graças e Privilégios, 1636, Arquivo Nacional Torre do Tombo (ANTT), Convento da Madre de Deus de Lisboa, mç. 1, doc. 45).

36 Sumário das Graças e Privilégios.

37 Cópia de um Breve de Júlio II, sixteenth century, ADL, Dep. VI/25/A/4, n°2.

38 Although generally accepted as being authored by Colette herself, according to Richards, “Franciscan Women,” 19, Colette asked William of Casale to write the Constitutions under her direction. Colette wrote other texts that might have influenced the constitutions’ redaction, such as the Avis and the Sentiments, focusing on her spirituality and the Intentions, the Petites Ordonnances, and the Ordonnances, which have a more legislative nature. On these texts, see Lopez, Culture et sainteté, 227–51; Roest, “A Textual Community in the Making,” 163–80.

39 Roest, Order and Disorder, 174–75. For a detailed analysis of the content of the constitutions, see Lopez, Culture et sainteté, 206–14.

40 According to Roest, Order and Disorder, 175, this level of uniformity was a novelty among the Clarisses as, through these sets of texts, the Colettines reached a level of uniformity that had never been observed in the unreformed Urbanist Clarisses or even in the Observant network.

41 Regra de Santa Clara, c. 1496–1508, ADL, CRSC. Edited in Gomes, “Uma Regra de Santa Clara de Assis,” 139–59. Through palaeographical analysis, Gomes situated the codex’s production after 1496, when the convent was founded, and within the first years of the sixteenth century. The filigree decorations of Mudejar inspiration also favour this chronology.

42 Here in the version of 1216 by Innocent III, the originality of which is still questioned, as the earliest known copies date from the fifteenth century (Regola di Santa Chiara, c. 1460–1500, Monastero di Mentevergine, M sic, fols. 25v–26v; Samlingshandskrift, c. 1400–1450; c. 1416–20; 1417, Uppsala, Universitetsbibliotek, Cod. 63, fols. 180r–180v). Earlier surviving copies present, instead, a version issued in 1228 by Gregory IX. For more on this question see Cusato, “From the Perfectio,” 123–44. Similar doubts have been raised regarding Clare’s Testament. However, the discovery of late thirteenth- and fourteenth-century exemplars in Italy has contributed to changing some of these views. See Langeli, Gli Autografi, 104–30; Ciccarelli, “Volgarizzamenti Siciliani,” 19–51; Roest, Order and Disorder, 297–98.

43 I refer to “para-normative texts” as those that complemented the official normative documents, which were the Rule of Saint Clare, approved in 1253 by Innocent IV, and the Colettine Constitutions, confirmed by Pius II in 1458.

44 For a detailed study of these texts, see Becker, Godet, and Matura, Ecrits/Claire d’Assise.

45 As can be read in a sixteenth-century Portuguese translation of the Constitutions: Regra de Santa Clara, c. 1541–1566, Biblioteca Municipal de Faro (BMF), Cod. 03347, fol. 60r.

46 Regra de Santa Clara, c. 1496–1508, ADL, CRSC (fly-leaf).

47 Gomes, “Uma Regra de Santa Clara de Assis,” 143.

48 Regra de Santa Clara, c. 1541–1566, BMF, Cod. 03347, fol. 22v; S. João, livro 2, cap. 6, fol. 71r.

49 These codices usually contain the First Rule of Saint Clare, the Privilege of Poverty and Saint Clare’s Testament and Blessing. In regions where Colettine convents existed, such as Portugal and Spain, these volumes may also contain the Colettine constitutions. Some codices may also contain important papal bulls for the Clarisses, such as the Ordinis tui issued by Innocent IV in 1446, which assured their connection to the Franciscans. For more on surviving codices in Italy, see Umiker, “La Regola di S. Chiara,” 115–52; Ciccarelli, “Volgarizzamenti Siciliani.”

50 By the time the Convent of Setúbal was founded in 1496, there was only one Observant house of Clares – the Convent of Immaculate Conception in Beja – which, as noted, adopted the Urbanist Rule. The same happened with the other convents reformed within Observance, see Rodrigues, Fontes, and Andrade, “La(s) reforma(s) en el franciscanismo portugués,” 60.

51 As indicated in the books’ colophons (Regra de Santa Clara, 1523, BNP, Il. 208, fol. 69v; Regra de Santa Clara, sixteenth century, Biblioteca Pública de Évora (BPE), cod. CXIII/1–43, fol. 59v).

52 Gomes, “Uma Regra de Santa Clara de Assis,” 142.

53 With the exception of Saint Clare’s blessing, not included in this volume, and the Privilege of Poverty, which was arguably added to the volume in the second half of the sixteenth century, as evidenced by the characteristics of the handwriting. The book, hereafter the “codex from Burgos,” is kept in the library of the Benedictine monks of Santo Domingo de Silos in Burgos, Spain, to whom I’m deeply grateful for facilitating the consultation of the volume. (Regla de Santa Clara, sixteenth century, Archivo Monasterio de Silos [AMS], Ms. 18). The Latin text of the Rule of Saint Clare also circulated in Spain in this period; it is included in a sixteenth-century miscellany kept in the Archivo Histórico Nacional in Madrid (Regulas religionum, 1500, Archivo Histórico Nacional, L. 1258, fols. CCIL–CCLXXXI).

54 Regla de Santa Clara, sixteenth century, AMS, Ms.18, fol. 25v. The book was later used by another nun named Madalena, as indicated in the manuscript’s fly-leaf.

55 Known through a copy made directly from the bull in 1420, which was the source for the version presented in a codex from S. Chiara of Urbino copied in 1456 (Regola di Santa Chiara, 1456, Monastero S. Chiara, sigla B).

56 A small difference in the chapter concerning the reception of the novices separates the two versions. The text from Setúbal mentions only that the novices should take the veil after the probation year has ended (Regra de Santa Clara, c. 1496–1508, ADL, CRSC, fol. 4r), whereas the Burgos codex adds that they should also maintain their way of life and poverty perpetually (Regla de Santa Clara, sixteenth century, AMS, Ms.18, fol. 5v). All the analysed versions are in accordance with the Burgos codex and the original version of Assisi; it was not possible to identify the source of Setubal’s text, which is repeated in another codex made for this convent in 1531 (Regra de Santa Clara, 1531, BNP, Cod. 7684). However, the two versions co-existed in Setúbal, as a codex made in 1560 for this convent by the community’s confessor, António de Tomar, presents the original version of Assisi (Regra de Santa Clara, 1560, Biblioteca do Museu Nacional de Arqueologia (BMNARQ), Ms/COD/33, fol. 3v).

57 Both vernacularisations of the Testament are in accordance with the Latin version that circulated in Italy in the fifteenth century, as can be seen in the codices of Messina (Regola di Santa Chiara, c. 1460–1500, Monastero di Mentevergine, M sic) and Urbino (Regola di Santa Chiara, 1456, Monastero S. Chiara, sigla B). As for the Privilege of Poverty, as in the codex from Messina, both vernacular versions present the document issued by Innocent III in 1216 and appear to have come from a Latin source that, while not possible to identify, appears in an early fifteenth-century codex from the convent of the Bridgettine abbey of Vadstena (Samlingshandskrift, c. 1400–1450; c. 1416–20; 1417, Universitetsbibliotek, Cod. 63, fol. 180r–180v), which was edited in the Firmamenta trium ordinum published in Paris in 1512. See Ceva, Firmamenta trium ordinum, part V:5.

58 Unlike the two earlier surviving volumes of the Rule of Saint Clare (Regra de Santa Clara, c. 1496–1508, ADL, CRSC; Regra de Santa Clara, 1531, BNP, Cod. 7684), the codex copied in 1560 by the community’s confessor, António de Tomar, contains the Colettine Constitutions (Regra de Santa Clara, 1560, BMNARQ, Ms/COD/33, fols. 20r–58r).

59 Memórias históricas, c. 1796–1803, ANTT, Manuscritos da Livraria, n° 846, fol. 96r.

60 The prologue is transcribed by Ivars, “Origen y propagación (Continuación),” 84–108. According to Ivars the original document did not survive but its content was preserved in a copy made for the Convent of Jerusalén in Valencia in 1525.

61 Regra de Santa Clara, c. 1541–1566, BMF, Cod. 03347, fols. 55v and 60r.

62 Regra de Santa Clara,1523, BNP, Il. 208, fol. 26r–69v.

63 A 1298 confirmation to the bull Quasdam Litteras issued by Boniface VIII (r. 1294–1303) in 1296 and the bull Licet Romanus Pontifex issued by Eugene IV (r. 1431–1447) in 1439.

64 Ivars, “Origen y propagación (Continuación),” 90–91.

65 Regra de Santa Clara, c. 1500–1550, BNP, Il. 211; Regra de Santa Clara, c. 1600–1650, BPE. Cod. Manizola, 262.

66 Regra de Santa Clara, c. 1541–1566, BMF, cod. 03347. An inscription in the fly-leaf states that the book was written by Sister Inês d’Ascenção, the convent’s first abbess from its foundation in 1541 until her death in 1566.

67 Regra de Santa Clara, sixteenth century, BPE, Cod. CXXIVd/2–28; Belém, Chronica serafica, 3:10.

68 Regra de Santa Clara, c. 1500–1550 BNP, Il. 177.

69 Regra de Santa Clara, sixteenth century, BPE, Cod. CXXIVd/2–28.

70 Ivars, “Origen y propagación (Continuación),” 89n2.

71 According to Ivars, “Origen y propagación (Continuación),” 89, seventeenth-century editions of Zarzuela’s version of the constitutions can be found in the libraries of most Colettine houses of Spain, which leads the author to assume that Zarzuela’s version was the only one used in Spain. However, he seems not to have known of the codex from Burgos.

72 Similar codices produced for the Observant Clarissan convents in Italy in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries often contain papal bulls as well, although not these particular ones. Most of these codices contain only the bull Ordinis tui issued by Eugene IV in 1447, confirming that the Clares were under the jurisdiction of the Franciscan Vicar General and making some clarifications on the First Rule, namely regarding its binding precepts. Some also contain the bull issued by Innocent IV in 1253, approving the First Rule. The inclusion of papal bulls in Friar Diogo’s codex was probably inspired by this Italian tradition. On the surviving Italian codices, see Ciccarelli, “Volgarizzamenti Siciliani;” Umiker, “La Regola di S. Chiara.”

73 As mentioned, according to the Colettine Constitutions, the novices should profess their vows while the abbess held their hands over the text of the Rule of Saint Clare.

74 For the early version, Regra de Santa Clara, 1523, BNP, Il. 208, fols. 31v–32r. For Zarzuela’s version, Regra de Santa Clara, c. 1541–1566, BMF, Cod. 03347, fols. 22v–23r.

75 Regra de Santa Clara, BNP, 1523, Il. 208, fol. 65v; Regra de Santa Clara, BMF, c. 1541–1566, Cod. 03347, fols. 55v–56r.

76 Regra de Santa Clara, BNP, 1523, Il. 208, fol. 39.

77 Regra de Santa Clara, BMF, c. 1541–1566, Cod. 03347, fol. 31v. Saint Francis’s words originally came from the forma vitae he wrote for the sisters of Saint Damian in Assisi, which we know only through Saint Clare’s references in the text of her own Rule. See Knox, Creating Clare of Assisi, 24.

78 Regra de Santa Clara, BPE, sixteenth century, Cod. CXIII/1–43, fol. 59v.

79 A colophon in a copy of the Urbanist Rule copied by the friar for the Convent of Santa Clara in Vila do Conde in 1576 informs us that the friar was seventy years old at the time he finished the copy, which reveals his date of birth (this codex was sold by the Livraria Castro e Silva, reference 1304JC018).

80 Belém, Chronica Serafica, 1:69.

81 Regra de Santa Clara, 1560, BMNARQ, Ms/COD/33, fol. 17v; S. João, livro 5, cap. 31, fol. 226r.

82 In addition to the mentioned copy of the Urbanist Rule, copied by the friar for the Convent of Santa Clara in Vila do Conde in 1576, and the 1560 volume he made for the convent of Setúbal, the extinction inventory for the convent of Monte Calvário in Évora started with nuns who came from Setúbal in 1565 mentions a copy of the First Rule made by Friar António de Tomar (Termo d’entrega, 1857, ANTT, Ministério das Finanças, Convento de Santa Helena do Calvário de Évora, cx. 1921).

83 Sousa, A Rainha D. Leonor, 560, suggested that Friar António de Tomar made his book between 1509 (when Coleta Talhada moved to Madre de Deus) and 1523, when Friar Diogo de Leiria finished the codex containing the Constitutions because of the absence of this text from the first codex. However, as shown, the existing records on Friar António de Tomar place this friar in a later chronology, which weakens Sousa’s hypothesis, as it is unlikely that the friar would have produced the mentioned codex before he was seventeen years old. Given that Coleta Talhada died in 1560 it is more plausible to place the production of the book at least between the 1530s and 1560. Moreover, the codicological and palaeographical characteristics of the codex are similar to those presented in the volumes produced by the friar for the convents of Setúbal and Vila do Conde in 1560 and 1575, placing the three exemplars in a closer chronology. In this case, the analysis by Sousa, A Rainha D. Leonor, 560–82, of the works of Diogo de Leiria and António de Tomar, based on the precedence of Tomar’s codex, should be reviewed.

84 Friar Diogo’s book measures 217×153 mm, while Friar António’s measures 135×100 mm.

85 In 1445, Giovanni Capistrano, Vicar General of the Franciscans of the Cismontane Province, wrote an explanation of the First Rule of Saint Clare, dividing it into 118 precepts, which clarified the nuns’ obligations towards their rule. For the edition of the Explicatio, see Andrichem, “Explicatio Primae Regulae,” 337–57, 512–29. For a historical contextualisation of the text, see Knox, Creating Clare of Assisi, 136–43. In his explanation of the First Rule, made in 1610 Miranda, Vida de la gloriosa Virgen Sancta Clara, 1–47, noted that, before this, similarly to what was done for the friars’ rule, the “ancient fathers” divided the rule of Saint Clare into seventy-five precepts, which he takes for his own explanation. António de Tomar’s comments on the rule do not follow those of previous authors, showing only forty-eight precepts: Regra de Santa Clara, sixteenth century, BPE, Cod. CXIII/1–43, fols. 2r–38r.

86 The codex Regra de Santa Clara, sixteenth century, BPE, Cod. CXXIVd/2–28 measuring 133×99 mm, bears the inscription “Soror Baptista da Encarnação” on the fly-leaf. The book from Burgos, with the dimensions 166×117 mm, was made for a specific nun, whose name appears in the formula of profession and was later used by other women as registered on the book’s fly-leaf.

87 Regra de Santa Clara, sixteenth century, BPE, Cod. CXXIVd/2–28, fols. 1r–25v.

88 Regra de Santa Clara, 1531, BNP, Cod. 7684.

89 Vida, feitos e milagres de Santa Clara de Assis, 1526, ANTT, Manuscritos da Livraria, n.° 738. For more on this text, see Sousa, A Rainha D. Leonor (1458–1525), 538–59.

90 Sobral, “O Flos Sanctorum de 1513,” 551.

91 Campbell, “Colette of Corbie,” 175.

92 Campbell, “Colette of Corbie,” 174–75.

93 According to Campbell, “Colette of Corbie,” 177, the Observants, whose power within the order overshadowed the Conventuals by the end of the fifteenth century, preferred to promote their own figures for canonisation. For a detailed explanation of the socio-political factors behind the delay in Colette’s beatification, see Campbell, “Colette of Corbie,” 173–89.

94 Pearson, “Imaging and Imagining Colette of Corbie,” 130–72.

95 For an overview of Colette’s scarce representation in art, see Gaulard, “Images du charisme,” 331–43.

96 Prior the authorisation of Colette’s cult in the early seventeenth century, I was only able to find a depiction of Colette labelled as beata in the Firmamenta trium ordinum, printed in Paris in 1512. See Ceva, Firmamenta trium ordinum, V: I and XVIIIv.

97 S. João, livro 1, cap. VIII, fols. 17v–18r.

98 According to Luís Reis Santos, the panel was probably made between 1491 and 1507; see Pereira, Cândido, and Anjos, Retábulo do Convento de Jesus de Setúbal, 33. Pereira suggests that the painting came to Portugal along with the relics of Saint Auta sent by Maximilian I to the convent of Madre de Deus of Lisbon along with other artworks in 1517, but he has overlooked the reference in Setubal’s chronicle which suggests that this painting might have been offered to the Convent of Setúbal prior to that date.

99 During a cleaning process in 1939, a fishing net with true-love knots – the emblem of Leonor de Lencastre – was found in the panel depicting the three saints being crowned by an angel, which led scholars to attribute the commissioning of the altarpiece to the dowager queen (see Pereira, Cândido, and Anjos, Retábulo do Convento de Jesus de Setúbal, 33). The altarpiece, as reconstituted in the 1980s, can be seen today in the Galeria Municipal de Setúbal in Setúbal.

100 Today in the Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga, Lisbon.

101 S. João, livro 5, cap XI, fol. 212v. The doors are preserved in the Museu de Setúbal/Convento de Jesus.

102 Museu de Lamego, n° 122/14.

103 Museu de Santa Clara de Gandía, MC122. Attributed to Jerónimo Jacinto de Espinosa (1600–1667).

104 For information about modifications in the painting, see the museum’s website (http://www.museusantaclaragandia.com/?artwork=santa-coleta).

105 Gonzales, “De convento a museo,” 96–100.

106 According to Ivars, “Origen y propagación,” 401, eight nuns were brought from Madre de Deus to found this convent. Furthermore, Margarita de Austria was also queen consort of Portugal (which was under Spanish domain from 1580 to 1640) and patron of Jesus of Setúbal: S. João, livro 5, cap XI, fol. 212v.

107 Campbell, “Colette of Corbie,” 175–76.

108 Douillet, Sainte Colette, 494–95. In 1604 the nuns were given permission to celebrate a mass and office in Colette’s honour on 6 March. During the following years this authorization was gradually extended to the Franciscan houses of Belgium (1610), France (1629) and finally to all the Franciscan order (1635).

109 Bizouard, Histoire de Sainte Colette, 265.

110 Vida de la bienaventurada sor Colecta, sixteenth century, Real Biblioteca, MD/F/53, fol. 61r. It was not possible to find evidence for Colette’s liturgical celebration in Portugal in this period, due to the lack of surviving liturgical sources.

111 This is not the life composed by Pierre de Vaux in 1448, but the text written by Colette’s companion Perrine de Baume, as indicated in the text’s prologue (Vida de la bienaventurada sor Colecta, sixteenth century, Real Biblioteca, MD/F/53, fol. 4r).

112 The third part of Lisboa’s Chronicles, including the text of Colette’s life, was edited in Portuguese in 1615 by Friar Luis dos Anjos.

Works Cited

Primary Sources

- Cópia de um Breve de Alexandre VI, seventeenth century, Arquivo Distrital de Leiria, Dep. VI/25/A/4, n°1.

- Leonor de S. João. Tratado da Antiga e Curiosa Fundação do Conu[ento] d[e] JESV. de Setuual, 1630, Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal, Cod. 7686.

- Memórias históricas, c. 1796–1803, Arquivo Nacional Torre do Tombo, Manuscritos da Livraria, n° 846.

- Regla de Santa Clara, sixteenth century, Archivo del Monasterio de Silos, Ms. 18.

- Regola di Santa Chiara, 1456, Monastero S. Chiara, sigla B.

- Regola di Santa Chiara, c. 1460–1500, Monastero di Mentevergine, M sic.

- Regra de Santa Clara, 1523, Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal, Il. 208.

- Regra de Santa Clara, 1531, Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal, Cod. 7684.

- Regra de Santa Clara, 1560, Biblioteca do Museu Nacional de Arqueologia, Ms/COD/33.

- Regra de Santa Clara, c. 1500–1550, Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal, Il. 211.

- Regra de Santa Clara, c. 1541–1566, Biblioteca Municipal de Faro (BMF), Cod. 03347.

- Regra de Santa Clara, c. 1600–1650, Biblioteca Pública de Évora. Cod. Manizola 262.

- Regra de Santa Clara, sixteenth century, Arquivo Distrital de Leiria, CRSC.

- Regra de Santa Clara, sixteenth century, Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal, BNP, Il. 177.

- Regra de Santa Clara, sixteenth century, Biblioteca Pública de Évora (BPE), cod. CXIII/1–43.

- Regra de Santa Clara, sixteenth century, Biblioteca Pública de Évora, Cod. CXXIVd/2-28.

- Regulas religionum, 1500, Archivo Histórico Nacional, L. 1258.

- Samlingshandskrift, 1400–1450; 1416–20; 1417, Uppsala, Universitetsbibliotek, Cod. 63.

- Sumário das Graças e Privilégios, 1636, Arquivo Nacional Torre do Tombo, Convento da Madre de Deus de Lisboa, mç. 1, doc. 45.

- Termo d’entrega à Inspecção Geral das Bibliothecas, 1857, Arquivo Nacional Torre do Tombo, Ministério das Finanças, Convento de Santa Helena do Calvário de Évora, cx. 1921.

- Vida de la bienaventurada sor Colecta, reformadora de la orden y regla de Santa Clara, sixteenth century, Real Biblioteca, MD/F/53.

- Vida, Feitos e Milagres de Santa Clara de Assis, 1526, Arquivo Nacional Torre do Tombo, Manuscritos da Livraria, n.° 738.

Secondary Sources

- Amorós Payá, León. “El monasterio de Santa Clara de Gandía y la familia ducal de los Borjas.” Archivo Ibero-Americano 20, no. 80 (1960): 441–86.

- Andrade, Maria Filomena. “‘Conhece a tua Vocação’: liberdade e graça nas Clarissas.” Lusitania Sacra 37 (2018): 77–91.