Abstract

Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights states that everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression. However, due to difficulties in communicating, children with speech, language and communication needs (SLCN) are at particular risk of not being heard. Although it is recommended that children with SLCN can and should be actively involved as equal partners in decision-making about their communication needs, speech–language pathologists (SLPs) can lose sight of the importance of supporting communication as a tool for the child to shape and influence choices available to them in their lives. Building these skills is particularly important for SLPs working in mainstream educational contexts. In this commentary, the authors argue the need for a shift in emphasis in current practice to a rights-based approach and for SLPs to take more of an active role in supporting children with SLCN to develop agency and be heard. We also present some concepts and frameworks that might guide SLPs to work in a right-based way in schools with this population.

Introduction

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights has formed the foundation of “freedom, justice and peace” for 70 years (United Nations, Citation1948, p. 1). Article 19 of the Declaration states communication, in any mode, is a human right. Subsequent Conventions also state children’s right to communication. For example, Article 12 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child (United Nations, Citation1989) names children’s right to expression and opinion about actions affecting them, while Article 13 names a child’s right to expression. Not all children have the capability to fully realise their right to communication. Some children such as those with speech language and communication needs (SLCN) will require additional support to do so.

The right to communication is particularly relevant in the school context because it is the vehicle through which all children, including those with SLCN, learn (Lamb, Jackson, Walstab, & Huo, Citation2015). The right of children with disabilities to an inclusive education, without discrimination and on the basis of equal opportunity, has since been described in Article 24 of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (United Nations, Citation2006), and recently clarified through General Comment No. 4 (United Nations Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, Citation2016). It has long been recognised, however, that the curriculum pedagogy and assessment can present barriers for children with such disabilities to participate in and benefit from their education (Norwich, Citation2013).

Speech–language pathologists (SLPs) are well positioned to support school-aged children with SLCN to enact their human right to communication and to have a voice in issues that affect them in school. There is, however, literature to suggest that the actualisation of these rights by policy-makers, researchers and professionals – including SLPs – are yet to be fully realised (Coppock & Gillett-Swan, Citation2016). In this commentary, we consider ways that SLPs can work to support children with SLCN and their teachers to identify and address barriers to communication, as well as to build the communication skills necessary for these children to develop agency. Such an approach can enable full access to learning and participation in education, thereby ensuring the child’s human rights are fully realised.

The role of SLPs in the school context

In the last 20 years, the work of SLPs has seen a shift from a purely medical model to a biopsychosocial one (Nippold, Citation2012). This is evidenced by current guidelines that inform practice (American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, Citation2010; Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists, Citation2016; Speech Pathology Australia, Citation2011; World Health Organization, Citation2007) where in addition to describing and remediating SLCN, the participation of the child is also maximised. We, however, challenge the degree to which emphasis is placed on participation in practice. This means there is a risk that the rights of children with SLCN may not be fully realised.

Despite an understanding that interview forms part of holistic assessment (Joffe & Nippold, Citation2012), findings from a review of assessment practices revealed that the sole use of psychometric testing remains the most common approach used by professionals such as SLPs (Lebeer, Citation2012). Furthermore, a national review of SLP services in the United Kingdom highlighted that SLPs do not always engage children in decision-making (Dockrell, Lindsay, Roulstone, & Law, Citation2014; Roulstone & Lindsay, Citation2012), despite the fact that children with SLCN have been shown to be able to reflect on their communication profile (Merrick & Roulstone, Citation2011; Spencer, Clegg, & Stackhouse, Citation2010). SLPs are well-positioned to ensure the views and preferences of the child are included in such processes but to do so they must think beyond diagnosis and remediation and overcome what Minow (Citation1990) describes as the “dilemma of difference”.

The dilemma of difference

The process of diagnosing SLCN requires SLPs to identify, understand and attempt to address differences between a child and their peers. While this process has merit in allowing the development of targeted interventions and responsive classroom practices, it also risks stigmatisation, formation of assumptions about a child’s potential, and their possible realisation through the self-fulfilling prophecy of lower expectations (Graham & Slee, Citation2008). The alternative, however, is to deny difference and herein lies the dilemma. The risk of not identifying difference is that children are unlikely to receive the requisite support for access and participation. The challenge for SLPs is how to identify and support children with SLCN without contributing to stigmatisation, exclusion and/or the reduction of expectations.

Much work remains to be done in addressing this challenge. Large-scale international surveys of SLP practice in schools show that withdrawal intervention is the dominant model of service delivery (Brandel & Loeb, Citation2011). This model has been criticised in the inclusive education research literature and not just because it emphasises individual difference and risks stigmatisation (Norwich, Citation2013). Withdrawal is considered problematic because it: (1) leaves mainstream educational practices that create barriers to children’s access and participation in place, (2) reduces exposure to the full school curriculum, (3) suggests that children’s needs cannot be met in the regular classroom and (4) fails to positively enhance the knowledge and skills of the classroom teacher. None of the above effects are consistent with a rights-based approach where children with SLCN are learning the communication skills needed to maximise agency and participation in school.

Thinking beyond remediation

Fundamental to trying to work in a rights-based way is ensuring children with SLCN can exercise agency in their own lives. Here, we are drawing on ideas from continental and political philosophy, and Amartya Sen’s (Citation1990) concept of agency freedom specifically. In accordance with this view of agency, genuine freedom only exists when people are informed, understand what choices are possible, and can choose from options of their own making. This is different from choosing from a limited set of choices, prescribed by others (Graham, Citation2007), or being provided with ‘opportunities’ that one cannot access or gain advantage from (Sen, Citation1992). For children with SLCN, there is the potential that SLPs and teachers determine the options from which children can choose. Similarly, the practice of withdrawing children for intervention is unhelpful when, on returning to class, barriers to access remain.

Clearly for children with SLCN to express preferences, negotiate and influence the choices available to them, they need the communication skills to do so. We are not arguing that improving the child’s language skills is not necessary. Rather, the way SLPs approach their work needs to be extended to directly supporting the child to learn to use communication skills to shape and influence their lives. Researchers have shown that children with SLCN want to be engaged in decision-making (Roulstone, Harding, & Morgan, Citation2016). To do so, SLPs must listen to children with SLCN, partner with teachers and build children’s communication skills using a rights-based approach.

Central elements for a rights-based approach

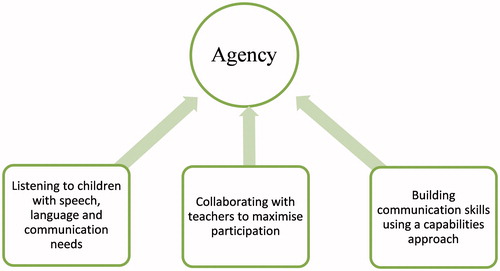

As we have described, the aim of a rights-based approach to working with children with SLCN is to develop agentive capacity to enable them to realise their rights. We propose three central elements of practice: (1) SLPs and teachers listen to children with SLCN, (2) SLPs and teachers collaborate to maximise children’s participation and, (3) SLPs work to build communication skills using a capabilities approach. The relationship between these elements and their contribution to the development of agency is depicted in .

Listening to children with SLCN

Working in a rights-based way requires the SLP to rethink the act of listening. Listening to children with SLCN has received attention in the research literature (Lyons & Roulstone, Citation2017; Roulstone & McLeod, Citation2011) and the complexities that teachers and SLPs face in genuinely hearing and responding to children with SLCN are significant. By listening we don’t mean listening as a means to “extract information from children in a one-way event” but as a “dynamic process which involves children and adults discussing meanings” (Clark, Citation2005, p. 491). In doing so SLPs must avoid the urge to “grasp the other and make them the same” (Lancaster & Kirby, Citation2010, p. 13). This advice is relevant to working with all children but particularly so for children with SLCN who may not be able to impart “meaning” in a readily accessible way. Strategies to support listening might include using multiple conversations (Merrick & Roulstone, Citation2011; Owen, Hayett, & Roulstone, Citation2004) and multi-modal prompting systems (Merrick & Roulstone, Citation2011; Owen et al., Citation2004), which enhance access to the communication partner’s message and give children with SLCN multiple opportunities to expand their ideas. Indeed, providing accessible and interactive materials for children with SLCN to use when contributing to decision-making was recommended in a recent report by The Communication Trust (Roulstone et al., Citation2016).

Collaborating with teachers

The ability to listen and respond to the needs of children with SLCN in school is dependent on effective SLP/teacher collaboration. Here, SLPs must shift away from the role of “expert” to one as collaborator. D’Amour et al. (Citation2005) describe collaboration as an evolving process, grounded in the concepts of equality, sharing, partnership, power and interdependence. As collaborators, SLPs are not in a position of “advice giving”, but instead are equal partners in the everyday work of classrooms. As part of the planning and assessment process, SLPs and teachers working together can identify and minimise/remove barriers that may exist for a child with SLCN in accessing the communication or curricular content of the classroom. In collaborating, SLPs and teachers can work to maximise agency for children with SLCN and thereby uphold their rights to communication and an inclusive education. While increasingly SLPs are engaging in collaborative models of service delivery (Archibald, Citation2017), many barriers to such working still exist (McCartney & Ellis, Citation2013).

Collaborative conversations can be guided by tools such as the Framework for Participation (Florian, Black-Hawkin, & Rouse, Citation2016), which describes key questions across four domains (participation and access, collaboration, achievement and diversity). We provide an adapted version of the framework (see Appendix) which can be used as a tool for teachers and SLPs to consider current practices and potential barriers that might exist for children with SLCN and to measure progress in reducing such barriers. This framework can also be used to guide conversations with the child him/herself to ensure their perspectives is included.

A capabilities approach to building communication skills

Due to difficulties such as SLCN, purely language-based instruction, will mean that not all learners can equally convert learning to ends such as academic achievement and engagement. In order to uphold a child’s right to an inclusive education and their right to communicate within an education setting, multiple means of representing information, engaging learners and capturing a child’s learning is necessary. Universal Design for Learning is a framework used in inclusive settings to engage the child in their learning, deliver dynamic instruction, and provide opportunities for the child to demonstrate their learning through a range of modes (Rose & Meyer, Citation2002). In contrast to traditional differentiation practices, Universal Design for Learning promotes that a variety of learning and teaching options are designed from the outset of planning, to consider diverse learning needs within a classroom. Using this framework when collaborating with teachers may support SLPs to capture and respond to the child’s perspectives and allow the child to communicate what helps and hinders them in accessing their education.

Conclusions

The 70th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights provides SLPs working in schools with an opportunity to pause and consider ways in which they can further protect and advance the right to communication for children with SLCN. In this commentary, we have reflected on the ways SLPs currently work in schools with children who have SLCN. We suggest a shift in emphasis is required if SLPs are to ensure the right of children to communication is fully realised. We propose some concepts and frameworks that might support SLPs to work in schools with children with SLCN in a way that is more aligned with the social and legal values enshrined in the Declaration. We acknowledge that a rights-based approach is challenging, but we argue that as a profession, SLPs are uniquely-placed to overcome such challenges.

Declaration of interest

There are no real or potential conflicts of interest related to the manuscript.

Aoife Gallagher is funded by the Health Research Board Ireland (SPHeRE/2013/1).

References

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2010). Roles and responsibilities of speech-language pathologists in schools.

- Archibald, L.M. (2017). SLP-educator classroom collaboration: A review to inform reason-based practice. Autism and Developmental Language Impairments, 2, 1–17. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/2396941516680369

- Brandel, J., & Loeb, F.D. (2011). Program intensity and service delivery models in the schools: SLP survey results. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 42, 461–490. doi:https://doi.org/10.1044/0161-1461(2011/10-0019)

- Clark, A. (2005). Listening to and involving young children: A review of research and practice. Early Child Development and Care, 175, 489–505. doi:10.1080/03004430500131288

- Coppock, V., & Gillett-Swan, J. (2016). Children’s rights, educational research and the UNCRC. In J. Gillett-Swan & V. Coppock (Eds.), Children’s rights, educational research and the UNCRC (pp. 7–16). Oxford, UK: Symposium Books.

- D’Amour, D., Ferrada-Videla, M., San Martin Rodriguez, L., & Beaulieu, M.D. (2005). The conceptual basis for interprofessional collaboration: Core concepts and theoretical frameworks. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 19(sup1), 116–131. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820500082529

- Dockrell, J., Lindsay, G., Roulstone, S., & Law, J. (2014). Supporting children with speech, language and communication needs: An overview of the results of the Better Communication Research Programme. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 49, 543–557. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12089

- Florian, L., Black-Hawkins, K., & Rouse, M. (2016). Achievement and inclusion in schools. Oxford, UK: Routledge.

- Graham, L.J. (2007). Towards equity in the futures market: Curriculum as a condition of access. Policy Futures in Education, 5, 535–555. doi:https://doi.org/10.2304/pfie.2007.5.4.535

- Graham, L.J., & Slee, R. (2008). An illusory interiority: Interrogating the discourse/s of inclusion. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 40, 277–293. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-5812.2007.00331.x

- Joffe, V.L., & Nippold, M.A. (2012). Progress in understanding adolescent language disorders. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 43, 438–444. doi:https://doi.org/10.1044/0161-1461(2012/12-0052)

- Lamb, S., Jackson, J., Walstab, A., & Huo, S. (2015). Educational opportunity in Australia 2015: Who succeeds and who misses out. Melbourne, Australia: Centre for International Research on Education Systems, Victoria University, for the Mitchell Institute. Retrieved from www.mitchellinstitute.org.au

- Lancaster, Y.P., & Kirby, P. (2010). Listening to young children. London, UK: McGraw-Hill Education.

- Lebeer, J., Birta-Székely, N., Demeter, K., Bohács, K., Candeias, A.A., Sønnesyn, G., … Dawson, L. (2012). Re-assessing the current assessment practice of children with special education needs in Europe. School Psychology International, 33, 69–92. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034311409975

- Lyons, R., & Roulstone, S. (2017). Labels, identity and narratives in children with primary speech and language impairments, International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 19, 503–518. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17549507.2016.1221455

- McCartney, E., & Ellis, S. (2013). The linguistically-aware teacher and the teacher-aware linguist. Clinical Linguistics and Phonetics, 27, 419–427. doi:https://doi.org/10.3109/02699206.2013.766763

- Merrick, R., & Roulstone, S. (2011). Children’s views of communication and speech-language pathology. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 13, 281–290. doi:https://doi.org/10.3109/17549507.2011.577809

- Minow, M. (1990). Making all the difference: Inclusion, exclusion and American law. New York, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Nippold, M.A. (2012). Times change and we with them. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 43, 393–394. doi:https://doi.org/10.1044/0161-1461(2012/ed-04)

- Norwich, B. (2013). Addressing tensions and dilemmas in inclusive education: Living with uncertainty. London, UK: Routledge.

- Owen, R., Hayett, L., & Roulstone, S. (2004). Children's views of speech and language therapy in school: Consulting children with communication difficulties. Child Language Teaching and Therapy, 20, 55–73. doi:https://doi.org/10.1191/0265659004ct263oa

- Rose, D.H., & Meyer, A. (2002). Teaching every student in the digital age: Universal design for learning. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

- Roulstone, S., Harding, S., & Morgan, L. (2016). Exploring the involvement of children and young people with speech, language and communication needs and their families in decision making: A research project. London, UK: The Communication Trust. Retrieved from https://www.thecommunicationtrust.org.uk/resources/resources/resources-for-practitioners/involving-cyp-with-slcn-research/

- Roulstone, S., & Lindsay, G. (2012). The perspectives of children and young people who have speech, language and communication needs, and their parents. London, UK: Department for Education.

- Roulstone, S., & McLeod, S. (Eds.) (2011). Listening to children and young people with speech, language and communication needs. London, UK: J&R Press.

- Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists. (2016). Speech and language therapists in schools. Retrieved from https://www.rcslt.org/members/slts_in_schools/role_of_the_slt

- Sen, A. (1990). Means versus freedoms. Philosophy and Public Affairs, 19, 111–121. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2265406

- Sen, A. (1992). Inequality reexamined. Cambridge, UK: Harvard University Press.

- Speech Pathology Australia. (2011). Position statement: Speech pathology services in schools. Retrieved from http://www.speakingoflearning.com.au/uploads/105/49/Sevices-in-Schools-Position-Statement.pdf

- Spencer, S., Clegg, J., & Stackhouse, J. (2010). ‘I don’t come out with big words like other people’: Interviewing adolescents as part of communication profiling. Child Language Teaching and Therapy, 26, 144–162. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0265659010368757

- United Nations. (1948). Universal declaration of human rights. Retrieved from http://www.un.org/en/universal-declaration-human-rights/index.html

- United Nations. (1989). Convention on the rights of the child. Retrieved from http://www2.ohchr.org/english/law/pdf/crc.pdf

- United Nations. (2006). Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities. Treaty Series, 2515, 3. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities.html

- United Nations Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. (2016). (2016, September 2) Article 24: Right to inclusive education, CRPD/C/GC/4. Retrieved from: http://www.refworld.org/docid/57c977e34.html

- World Health Organization. (2007). International classification of functioning, disability, and health: Children and youth version: ICF-CY. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

Appendix. Describing inclusive participation for children with speech, language and communication needs (SLCN)

Direct observation can be undertaken in relation to the points below in order to identify potential barriers to participation, options for how barriers could be addressed and evidence of change over time.