Abstract

Purpose

This paper describes a collaborative project between Trinity College Dublin in Ireland and the United Nations’ World Food Programme (WFP) Mozambique country office. The Sphere standards require that information on humanitarian assistance should be in languages and formats accessible to people who cannot read or who have communication difficulties. Nevertheless, there remains a gap in both implementing this guidance consistently and in understanding the impact of doing so when engaging with affected populations.

Method

This commentary describes the process of developing key messages regarding targeting of humanitarian food assistance in communication-accessible formats, and field testing of these materials with community committees and partners

Result

The communication-accessible materials were well received by communities, and humanitarian staff and partners found them to be useful in community engagement.

Conclusion

Materials designed to be maximally accessible to people with communication differences and disabilities may also address inclusion for affected populations with different education, literacy, and language backgrounds. This commentary focuses on Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 2 as an exemplar of the use of communication accessible messaging in humanitarian response.

Introduction

The United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are an ambitious commitment to an inclusive and more equal world, which is underpinned by 17 highly interconnected goals. SDG 2 is a commitment to “end hunger, achieve food security and nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture” (United Nations, Citation2015). The importance of disability inclusion with regards to SDG 2 is stark; available data on a subset of countries show that an average of 36% of households with persons with disabilities are food insecure, compared to 23% of households of persons without disabilities (United Nations, Citation2018).

In situations of humanitarian crises, access to food is a foundational need and affected populations, including persons with communication differences and communication disabilities, require accurate and timely information to facilitate that access. Much of the basic information provided is consistent across sectors (e.g. food assistance, shelter): what assistance is available, how eligibility is decided, and what feedback channels are available. Such information should adhere to the minimum standards of practice, as set out by The Sphere HandbookFootnote1 which require that information should be “in languages and formats accessible to people who cannot read or who have communication difficulties” (Sphere Association, Citation2018, p. 207). There remains a gap in how accessible information is typically implemented – a gap which could be addressed through the speech-language pathology evidence on communication-accessible materials.

This use-case example described in this paper is embedded in the ongoing response by the World Food Programme (WFP) to the humanitarian situation in Northern Mozambique. Key messages regarding food assistance and eligibility for assistance were developed in communication-accessible formats designed to be maximally accessible to people with communication differences and communication disabilities, who are typically some of the most marginalised and excluded in society (Wickenden, Citation2013). In designing information provision for those most at risk of being left behind, we hypothesised that we would increase information accessibility for all food insecure individuals in the region facing barriers to accessing basic information and food assistance. In keeping with the actively evolving situation, the prioritised information included what assistance is available, how eligibility is decided, how to maintain access to assistance over multiple displacements, and so forth. This use-case is therefore presented as an exemplar of how communication access can be integrated into humanitarian responses more broadly.

Food insecurity in Northern Mozambique

The United Nations World Food Programme, whose core mandate centres on SDG 2, is the world’s largest humanitarian organisation with active work in over 120 countries, one of which is Mozambique. In Northern Mozambique nearly a million people are facing severe hunger, a situation attributed to the impact of the armed conflict, resulting displacement of around 744,949 people (International Organisation of Migration (IOM), Citation2022), as well as the impact of extreme climate in recent years (IPC Analysis Citation2021). WFP reaches over 800,000 people in this region (WFP Mozambique country brief, January 2022).

As the conflict in Northern Mozambique moves into its fifth year, and funding is increasingly limited, WFP’s approach shifted from targeting persons for assistance based on their status (e.g. host or displaced population) to targeting based on vulnerability. Vulnerability-based targeting is a complex multi-stakeholder process, which is described here for context. Community committees, comprised of gender-balanced representatives from the host and displaced populations, including at least one person with a disability (or a family member), form the link between WFP and its cooperating partners – local, national and international non-government organisations which administer the assistance on the ground. Drawing on input from Community Committees and implementing partners, WFP determines the profiles of the households most vulnerable to or experiencing the highest levels of food insecurity. Households meeting these profiles are then identified, using house-to-house surveys in peri/urban, or community consultations in rural environments. In order to promote transparency and reduce tensions, providing community members with information on this process is crucial and is typically facilitated through the community committees, themselves with diverse linguistic and educational backgrounds.

Multilingual information provision in humanitarian response can reduce vulnerability and benefit the wider population (Vázquez & Torres-del-Rey, Citation2019), an important consideration in Mozambique where more than 40 languages spoken, with five primary languages in the Northern part of the country (Macua, Makonde, Kimwani, Swahili and Portuguese). Putting reliable, multilingual and easy-to-understand information in the hands of the cooperating partner teams and Community Committees, and providing training on how to use this approach, is a means to support inclusion and transparency.

The role of information access in humanitarian response

Effective and inclusive communication with affected populations goes beyond the content conveyed – it is essential to building trust, maintaining community cohesion and avoidance of doing harm (Sphere Association, Citation2018). For example, if food assistance is provided to one household but not to another, community conflict is more likely unless adequate information on how the selection process was conducted is shared. Effective communication can provide affected populations a degree of protection from the risks of assistance-related fraud (e.g. diversion of food provisions) and other abuses (Interagency Standing Committee (IASC), Citation2018). These risks are not tangential, but in fact central considerations in a people-centred response to food insecurity that respects the dignity of all affected people. A review of sexual exploitation and abuse in the food aid sector found “lack of clarity around entitlement and distribution of food aid” to be a specific risk for such exploitation, including in Mozambique (Rohwerder, Citation2022). The use of communication-accessible approaches for engaging with affected populations facing unequal barriers therefore has the potential to be an important risk mitigation tool by making critical information available to as many people as possible.

Communication-accessible materials are commonly used by speech-language pathologists to support access to information and conversation for people with communication disabilitiesFootnote2 and are associated with better comprehension of information (e.g. Saylor et al., Citation2022) and increased participation (e.g. Swinburn et al., Citation2007). Features associated with information designed for people with aphasia are supported by evidence (e.g. Saylor et al., Citation2022), but there is mixed evidence for the impact of the specific easy-to-read formats (e.g. Buell et al., Citation2020). Some of the common principles are outlined in . Evidence on the usefulness of graphics is mixed, and therefore images should be carefully chosen, with attention given to cultural acceptability, salient features of the key concept being conveyed, and consistency in style. Where funding allows, local illustrators can be engaged to develop the images in a consistent style. Where such resources are not available, the use of images or icon sets that maintain consistency and are acceptable to stakeholders should be considered.

Table I. Evidence-based principles used to design communication accessible material.

The majority of research on communication accessibility has been generated in countries where Western perspectives of interpersonal communication are privileged (Kong et al., Citation2021). Afrocentric theories of communication, of which there are many, should inform how approaches to information sharing are applied in Africa. Perhaps the most familiar of African metatheories is that of ubuntu, a philosophy based on a communal worldview that centres relationships as the location of personhood. Ubuntu encompasses sets of values that have their roots in numerous African countries south of the Sahara, including Mozambique, where the term is vumuntu. In proposing an ubuntu-centred approach to (health) communication, Ngondo and Klyueva (Citation2022) demonstrate how the specific ubuntu principles of inclusiveness, tolerance, transparency, and consensus-building allow for information sharing to go beyond individualism and focus on communities as a whole. Indeed, from this viewpoint, information sharing is inherently relational and embedded in communal responsibility. Consensus building through shared information is likely to be particularly important where populations include multilingual and displaced communities. Research in the Mozambican context suggests that oral communication, from trusted persons, who are socially (and linguistically) ‘closer’ to the recipients remains the “most powerful and affordable” means of access to information (Macueve et al., Citation2009, p. 24).

Method

This project aimed to explore the acceptability and practical use of communication-accessible materials addressing basic messages regarding food assistance in the context of WFP’s humanitarian response in Northern Mozambique. The introduction of communication-accessible supports within community engagement in Mozambique is part of a larger multi-country study on disability inclusion in food assistance programing. Ethical approval was granted by the relevant Research Ethics Committee in Trinity College Dublin.

Positionality and power

The authorship team represents a collaboration between researchers, based in Trinity College Dublin, and humanitarian practitioners based both in the WFP Mozambique country office and WFP headquarters. Despite varied ethnic, geographic, and occupational backgrounds, all members of the team experience privilege relative to those who receive assistance from WFP. As practitioners and research-practitioners, we acknowledge that we situate our work within the framework of humanitarian practice and a human rights-based approach and as such, this paper represents a particular world-view. The need for greater localisationFootnote3 in humanitarian action has been acknowledged, including developing more equal partnership between communities and local humanitarian actors (World Humanitarian Summit Secretariat, Citation2015). Establishing more equal partnership includes ensuring that individuals and their communities have the information to make informed choices about issues that affect them. The focus of the paper is therefore on how, within the existing boundaries of ethical humanitarian practice, greater inclusion can be achieved with regard to provision of information about food assistance.

While varying levels of power differentials exist across and between WFP staff, implementing partners, community committee members and the researchers, all represent individuals who are actively involved in the humanitarian response, providing assistance, participating in vulnerability-based targeting decisions, or facilitating information provision. The communication-accessible materials were therefore reviewed by persons with some decision-making power in terms of how the resources would (or would not) be implemented.

Design of communication-accessible materials

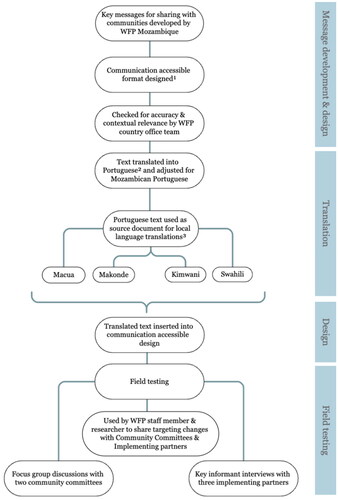

While there is evidence that individualised supports may be most effective (e.g. Chinn & Homeyard, Citation2017) and that some individual variation in preferences exists (e.g. Herbert et al., Citation2019), in the context of a rapidly evolving humanitarian emergency, a generic tool was required. The collaborative design process is outlined in . The resulting tool comprised of a 4-page laminated booklet of key messages for use within conversations, respecting the relational nature of information provision. In addition, large poster-size versions were prepared for use in communal contexts such as community meetings.

Figure 1. Process followed in development of communication accessible materials. 1By a speech-language pathologist (speech-language therapist in Ireland and Mozambique), using the principles outlined in . 2Forward and back translated by an accredited translator. 3Forward and back translated by experienced local translators across four minority languages, community checking by users.

“You took the words right out of my mouth!”: views of cooperating partners and community members on accessible communication materials

Implementing partners and community committee members reported that the materials were engaging and easy to understand, “with these drawings, with these colours, people are more motivated”. Communication supports were viewed as natural complement to diverse modes of information transfer: “it’s [the materials] a nice thing to take advantage of to complement communication…”. Users noted the utility of these supports for engaging marginalised populations beyond only those with communication disabilities. Low levels of literacy in Mozambique, especially for women (UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS), Citation2022), made the utility of images and simple text immediately apparent. The materials were viewed as having the potential to overcome issues of attention and recall “sometimes with the sensitisation people get the information, but they don’t remember it”. Community committees recognised the potential for wide application and expressed an intention to immediately start using the materials as a complement to other forms of communication.

Through supporting clarity of the information shared, reviewers anticipated that using the materials would help in decreasing community tensions:

Researcher: “You were talking about conflict… Does good communication help to decrease tension or conflict in the community in your opinions?”

National NGO staff-member: “Yes, you took the words right out of my mouth because its exactly like this! When there are tensions at the community level, often it’s because information has not been communicated well…”

WFP staff-member: “being able to say to them, give them the reason, justification [why some people are selected] so that means that people calm down and you’re not going to have that kind of clash at the distribution or people disrupting things.”

Reviewers recalled prior problems encountered with incorrect translation of key messages, with one staff member of a local NGO recalling,

one of the team members, who can understand Macua […] realized that the person who was translating wasn’t sending the right messages, was translating wrongly […] And that kind of raises the importance of making sure that those who translate know the language well

With five languages available, some users noted this was the first time in their work that they received materials in their own language, increasing the transparency of live translation, ensuring consistency and accuracy.

Summary and conclusion

Many groups of people face barriers in accessing information, including people with low levels of education or literacy, users of minority languages, people with disabilities, and in particular, those with communication disabilities. These groups experience a distinct risk of being left behind in food assistance and other humanitarian action. In contexts characterised by diverse languages and levels of education and literacy, employing an accessible communication approach has wide applicability beyond only disability inclusion. Our work suggests that such an approach is likely to contribute towards broader inclusion of affected populations. The use-case presented in this paper addressed messaging related to humanitarian, in-kind food assistance; however, in similar contexts there is clear scope for accessible messaging for targeted nutrition interventions (e.g. supplemental feeding). Speech-language pathologists are well placed to collaborate and advise on the development of communication accessible materials.

In harmony with an ubuntu-centred philosophy and the values of inclusiveness, transparency, tolerance, and consensus building, the approach taken was one that respected a relational and communal perspective on information sharing. The approach sought to address the accessibility (inclusiveness) and accuracy (transparency) of the information, with the purpose of promoting community cohesion (tolerance and consensus building). Further theorising and participatory research are needed to understand how the written and pictorial format interacts with the core principles of this approach.

While communication-accessible materials may initially seem to be a specialised resource for a niche population, a preference for receiving information in a communication-accessible format has been expressed by both people with and without communication disabilities (Saylor et al., Citation2022; Jagoe et al., 2023). The benefits and potential for risk mitigation for the broader population therefore outweigh the resource-demands (time, expertise), making communication accessible information an important and under-utilised tool in humanitarian practice. We call on humanitarian actors, who frequently engage face-to-face with affected populations, to prioritise the use of accessible communication in their work. We propose that communication supports as described in this paper can aid in the achievement of the SDGs for marginalised groups, including persons with communication disabilities.

Declaration of interest

This research was conducted as part of a funded partnership between WFP and Trinity College Dublin.

Notes

1 The handbook which outlines the Humanitarian Charter and Minimum Standards in Humanitarian response.

2 For the purposes of this commentary, communication disabilities are understood as an impairment in the functions of speech, language or cognition, which, in interaction with barriers in the environment, affect a person’s ability to understand others or to effectively and efficiently make themselves understood when using a preferred language.

3 It is beyond the scope of this brief commentary to discuss the colonial roots of humanitarian aid.

References

- Buell, S., Langdon, P.E., Pounds, G., & Bunning, K. (2020). An open randomized controlled trial of the effects of linguistic simplification and mediation on the comprehension of “easy read” text by people with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 33, 219–231. doi:10.1111/jar.12666

- Chinn, D., & Homeyard, C. (2017). Easy read and accessible information for people with intellectual disabilities: Is it worth it? A meta‐narrative literature review. Health Expectations, 20, 1189–1200. doi:10.1111/hex.12520

- Fajardo, I., Ávila, V., Ferrer, A., Tavares, G., Gómez, M., & Hernández, A. (2014). Easy‐to‐read texts for students with intellectual disability: Linguistic factors affecting comprehension. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 27, 212–225. doi:10.1111/jar.12065

- Herbert, R., Gregory, E., & Haw, C. (2019). Collaborative design of accessible information with people with aphasia. Aphasiology, 33, 1504–1530. doi:10.1080/02687038.2018.1546822

- Interagency Standing Committee (IASC) (2018). Plan for accelerating protection from sexual exploitation and abuse in humanitarian response at country-level. https://interagencystandingcommittee.org/system/files/iasc_plan_for_accelerating_psea_in_humanitarian_response.pdf

- International Organisation of Migration (IOM) (2022). Displacement tracking matrix (Mozambique). https://dtm.iom.int/mozambique

- IPC Analysis (2021). Mozambique: Acute food insecurity situation November 2021 - March 2022. https://www.ipcinfo.org/ipc-country-analysis/details-map/es/c/1155342/

- Jayes, M., & Palmer, R. (2014). Initial evaluation of the Consent Support Tool: A structured procedure to facilitate the inclusion and engagement of people with aphasia in the informed consent process. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 16, 159–168. doi:10.3109/17549507.2013.795999

- Kong, A.P.H., Chan, K.P.Y., & Jagoe, C. (2021). Systematic review of training communication partners of Chinese-speaking persons with aphasia. Archives of Rehabilitation Research and Clinical Translation, 3, 100152. doi:10.1016/j.arrct.2021.100152

- Macueve, G., Mandlate, J., Ginger, L., Gaster, P., & Macome, E. (2009). Women’s use of information and communication technologies in Mozambique: A tool for empowerment. In I. Buskens & A. Webb (Eds). African women and ICTs: Investigating technology, gender and empowerment (pp. 21–32). London: Zed Books.

- Ngondo, P.S., & Klyueva, A. (2022). Toward an ubuntu-centered approach to health communication theory and practice. Review of Communication, 22, 25–41. doi:10.1080/15358593.2021.2024871

- Rohwerder, B. (2022). Sexual exploitation, abuse and harassment in the food security sector. K4D Helpdesk report. https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/bitstream/handle/20.500.12413/17441/1097_SEAH%20in%20the%20food%20security%20sector.pdf?sequence=4

- Rose, T.A., Worrall, L.E., Hickson, L.M., & Hoffmann, T.C. (2011). Aphasia friendly written health information: Content and design characteristics. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 13, 335–347. doi:10.3109/17549507.2011.560396

- Saylor, A., Wallace, S.E., Brown, E.D., & Schreiber, J. (2022). Aphasia-friendly medication instructions: Effects on comprehension in persons with and without aphasia. Aphasiology, 36, 251–267. doi:10.1080/02687038.2021.1873907

- Sphere Association. (2018). The Sphere handbook: Humanitarian charter and minimum standards in humanitarian response (4th ed.). www.spherestandards.org/handbook

- Swinburn, K., Parr, S., & Pound, C. (2007). Including people with communication disability in stroke research and consultation: A guide for researchers and service providers. Connect.

- UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) (2022). Country dashboard (Mozambique), Education indicators. http://sdg4-data.uis.unesco.org/

- United Nations (2015). Sustainable Development Goals: 17 goals to transform our world. https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/

- United Nations. (2018). Realizing the sustainable development goals by, for and with persons with disabilities: UN report on disability and development 2018. https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/wp-content/uploads/sites/15/2018/12/UN-Flagship-Report-Disability.pdf

- Vázquez, S.R., & Torres-del-Rey, J. (2019). Accessibility of multilingual information in cascading crises. In S. R. Vázquez & J. Torres-del-Rey (Eds). Translation in cascading crises (pp. 91–111). London: Routledge.

- Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG 2.1). (2018). https://www.w3.org/TR/WCAG21/

- Wickenden, M. (2013). Widening the SLP lens: How can we improve the wellbeing of people with communication disabilities globally. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 15, 14–20. doi:10.3109/17549507.2012.726276

- World Humanitarian Summit Secretariat (2015). Restoring humanity: Global voices calling for action. New York: United Nations. https://reliefweb.int/report/world/restoring-humanity-global-voices-calling-action-synthesis-consultation-process-world