Abstract

Purpose: Over 140 000 Australians live with aphasia after stroke, with this number of people living with aphasia increasing significantly when aphasia arising from traumatic brain injury, neoplasm, and infectious and progressive neurological diseases is also included. The resulting communication disability frequently compromises every aspect of daily life, significantly impacting everyday activity, employment, social participation, mental health, identity, and family functioning. Rehabilitation services rarely meet the needs of this group who have, for example, poorer healthcare outcomes than stroke peers without aphasia, nor address long-term recovery and support needs.

Method: In this discussion paper, I argue that given the broad impacts of aphasia, a biopsychosocial approach to aphasia rehabilitation is required. Rehabilitation must include: interventions to improve the communication environment; programs that directly target identity, wellbeing, and mental health; and therapies focusing on functional activity, communication participation, and long-term self-management.

Result: The evidence for these approaches is mounting and includes strongly stated consumer needs. I discuss the need for multidisciplinary involvement and argue that for speech-language pathologists to achieve such comprehensive service provision, an expanded scope of practice is required.

Conclusion: There is a need to rethink standard therapy approaches, timeframes, and funding mechanisms. It is time to reflect on our practice borders to ask what must change and define how change can be achieved.

Over 140 000 Australians live with aphasia after stroke, with 24% of this population under 54 years of age (Deloitte Access Economics, Citation2020). The resulting communication disability frequently compromises every aspect of daily life, significantly impacting employment (Engelter et al., Citation2006), social participation (Davidson et al., Citation2008; Vickers, Citation2010), mental health (Hilari et al., Citation2010; Kauhanen et al., Citation2000), identity (Corsten et al., Citation2014; Shadden, Citation2005), family functioning (Grawburg et al., Citation2013), and quality of life (Lam & Wodchis, Citation2010). Rehabilitation services rarely meet the needs of this group, who have higher healthcare costs (Brogan et al., Citation2022) but poorer healthcare outcomes than stroke peers without aphasia (Bartlett et al., Citation2008; Sullivan & Harding, Citation2019), nor address long-term recovery and support needs (Deloitte Access Economics, Citation2020).

In this discussion paper, I argue that given the broad and significant long-term impacts of aphasia, a biopsychosocial approach to aphasia rehabilitation is essential within a model of chronic health management. Rehabilitation must include: interventions to improve communication environments; programs that directly target identity, wellbeing, and mental health; and therapies that focus on functional activity, communication participation, and long-term self-management. In this paper, I review the mounting evidence for these approaches including strongly stated consumer needs. I discuss the need for multidisciplinary involvement to achieve such comprehensive service provision, the potential of technology solutions to enhance management, and the need for an expanded scope of practice for many speech-language pathologists. Despite having evidence-based best practice statements that call for these broader aphasia management practices (Simmons-Mackie et al., Citation2017), a clear evidence-practice gap remains. There is a need to rethink standard therapy timeframes and funding mechanisms. It is time to ask what must change and define how change can be achieved.

The need for a biopsychosocial approach to aphasia management

In a biomedical model of health care, the focus is on the biological factors that cause disease and ill-health (Engel, Citation1977). Diagnosis focuses on which physical systems are impaired and intervention focuses on repairing the damaged systems. The biomedical model of healthcare has dominated aphasia management in hospitals, with an emphasis on dysphagia assessment and management over and above communication in acute care (Foster et al., Citation2016a, Citation2016b) and on impairment/language focused approaches in subacute care (Rose et al., Citation2014).

In 1977, a US psychiatrist, Dr. George Engel, questioned the dominant biomedical model and argued that models of healthcare should also include psychological and social factors (Engel, Citation1977). Engel believed that biological, psychological, and social factors interact to create an individual’s disease and ill-health, and that all of these factors could be targets of intervention. This idea underpins the World Health Organization’s (WHO’s) International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF; WHO, Citation2001), which is frequently discussed in the field of speech-language pathology but is yet to be fully realised in aphasia management.

The evidence-practice gaps

Despite the face validity of the ICF and a highly communicatively accessible reimaging of the ICF for aphasia, the Framework for Outcome Measurement in Aphasia (A-FROM; Kagan et al., Citation2008), aphasia management has focused more narrowly on impairment level interventions with far less attention given to functional and wellbeing goals (Rose et al., Citation2014). This is despite double the prevalence of anxiety and depression in people living with aphasia compared to their non-aphasia stroke peers (Mitchell et al., Citation2017; Morris et al., Citation2017) and the fact that identity is significantly challenged, with aphasia being a major biographical disruption (Corsten et al., Citation2015). The negative impacts of aphasia also extend to families and carers. A Swedish survey of carers (n = 173) reported 80% had stopped work or reduced their work hours, 80% had reduced leisure time, 50% had reduced social interaction, and 50% reported worse psychological health since caring for their partner with aphasia (Johansson et al., Citation2022). A recent systematic review confirms that these high levels of unmet carer need extend to the long-term (Denham et al., Citation2022).

Data for inadequate service provision is indisputable. The Stroke Foundation’s national stroke audit of Australian rehabilitation services found that 75% of services were not providing the recommended amount of therapy, 22% of patients were discharged home without a collaboratively developed care plan, and <50% of people with aphasia and their carers were offered information about peer support or longer-term care (Stroke Foundation, Citation2020). Further, a large cohort study of Queensland stroke care showed: very low levels of total inpatient (median 29 hours) and community-based (median 6 hours) rehabilitation across speech therapy, occupational therapy, and physiotherapy; a reduced length of stay (median 21 days); and a lack of intensive programs (Grimley et al., Citation2020). While the Australian National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) has been suggested as a way to address community-level service gaps for stroke survivors under 65 years of age, recent data confirm that less than 1.4% of NDIS participants with an approved plan have a stroke as their primary disability, equating to approximately 1.3% of eligible stroke survivors (Stroke Foundation, Citation2020). Finally, communication is at least a dialogical phenomenon. Therefore, conversation partners can be targets of intervention and communicative environments can be enhanced to enable improved communicative functioning (Simmons-Mackie et al., Citation2016) but to date, there are no system-wide conversation partner training programs or environmental enrichment strategies in stroke care (DSouza et al., Citation2021).

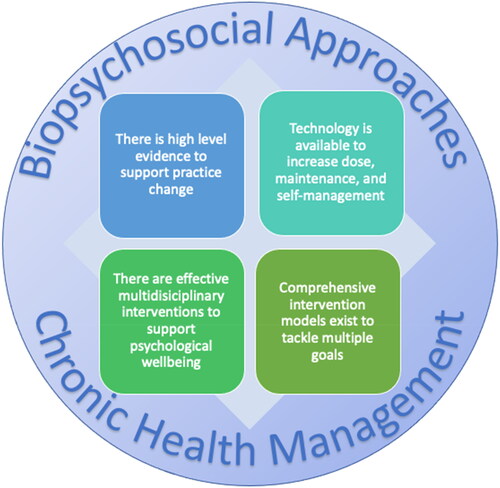

Given the broad and long-term sequelae of aphasia it seems clear that aphasia rehabilitation and management must include: interventions to improve the communication environment; programs that directly target identity, wellbeing, mental health, and family needs; and therapies focusing on functional activity, communication participation, and long-term self-management. The evidence-practice gaps are not solely the responsibility of speech-language pathologists. To be clear, in the 40 years I have practised, taught, and researched in aphasia rehabilitation, I have mostly worked with highly motivated, innovative, and brave speech-language pathologists, who are trying their absolute best to provide high-quality services to people with aphasia. However, resource limitations, staffing inadequacies, and policy restrictions frequently prevent innovation and growth in service provision. Given that the barriers to bridging the evidence-practice gaps are substantial, I now summarise four potential ways forward aimed at addressing these service gaps, reviewing the evidence that supports the strategies, and describing the potential for improved outcomes and service efficiency (see ). I hope that clinicians will be inspired and reinvigorated to band together and strategically tackle the barriers.

Way forward #1: There is strong evidence for the effectiveness of aphasia therapy as a basis for advocacy for practice change

The most recent Cochrane Collaboration review of speech and language therapy for aphasia after stroke (Brady et al., Citation2016) demonstrated improved functional communication, reading, writing, and expressive language immediately after aphasia intervention but not at follow-up (27 comparisons, n = 1620; standardised mean difference 0.28, CI 0.06–0.49, p = 0.01; Moderate GRADE framework quality; Guyatt et al. Citation2008). There was an indication that functional communication was significantly better after therapy given at high intensity, high dose, or for a long duration (38 comparisons, 1242 participants). Three more recent high-quality phase III randomised controlled trials (RCTs) have added further weight to the effectiveness of aphasia therapy for individuals with chronic aphasia (>6 months post-stroke). The From Controlled Experimental Trial 2 Everyday Communication (FECT2EC) trial (n = 156) showed that 3 weeks of intensive speech and language therapy (30 hours over 3 weeks + home practice) provided under routine clinical conditions led to significantly improved verbal communication in daily life and quality of life, while therapy given at 1.5 hours per week did not (Breitenstein et al., Citation2017). The gains were maintained in the presence of a small 1 hour per week maintenance dose, while a subgroup of participants who received 50 hours of therapy produced even greater gains. The Big CACTUS RCT (n = 278; Palmer et al., Citation2019) showed significantly improved naming after 20–30 minutes per day of self-managed computer naming therapy over 6 months. The improved naming was maintained at 12 months follow-up, with the computer-delivered therapy being half the cost of face-to-face therapy. The COMPARE RCT (n = 216) showed significantly improved naming, functional communication, and communication related quality of life following 30 hours of either multi-modality aphasia therapy or constraint induced aphasia therapy delivered over 2 weeks in groups of three participants compared to usual care, with naming gains maintained at 12 week follow-up. A substudy showed similar results with the 30 hour dose distributed across five rather than 2 weeks (Pierce et al., Citation2023). Additional data supporting aphasia therapy effectiveness was provided by the RELEASE Collaboration (Brady et al., Citation2022a, Citation2022b). In a large metaanalysis of individual patient data from 25 RCTs (n = 959) the greatest functional communication gains were associated with 20–50 hours of therapy, provided at 3–4 hours per week, for 4–5 days per week. Importantly, the little gain was seen in auditory comprehension outcomes for doses <20 hours, <3 hours per week, and < 3 days per week (Brady et al., Citation2022a).

Together these data argue strongly that aphasia therapy is effective when provided in sufficient dose and intensity, even for individuals in the chronic phase of recovery. However, clinical practice rarely offers these effective doses (Palmer et al., Citation2018; Rose et al., Citation2014; Verna et al., Citation2009). Further, a recent systematic review showed that maintenance of therapy effects is not universal; in fact, only 22% of individuals maintained their gains following intensive interventions, most of whom did not receive formal maintenance programs (Menahemi-Falkov et al., Citation2022). So how can we move towards implementing these effective doses and maintaining the positive effects? Technology offers some solutions.

Way forward #2: Technology can help increase dose, support maintenance, and enable long-term self-management

Recent developments in technology have underpinned innovation in computer-based aphasia interventions (see Aphasia Software Finder for a repository of intervention apps and computer programs: https://www.aphasiasoftwarefinder.org/), and research is emerging to support the efficacy of these therapy tools. One highly innovative approach is the EVA Park program, codesigned by people living with aphasia, and aphasia therapy and human-computer interaction experts at City University, London (https://evapark.city.ac.uk/). EVA Park is an online virtual world where multiple users with aphasia can meet to engage in aphasia therapy, practice communication, and develop social connections (Marshall et al., Citation2018). The delivery of a range of aphasia therapies within EVA Park has been pilot tested including functional conversation therapy (Marshall et al., Citation2020) and storytelling therapy (Carragher et al., Citation2021). In the conversation therapy study (Marshall et al., Citation2020), 20 participants with aphasia accessed EVA Park for 1 hour per day, 5 days per week, for 5 weeks (25 hours) and showed significant gains on both the Communication Activities of Daily Living Test (CADL-2; Holland et al., Citation1999) and measures of word retrieval in conversation following the conversational therapy. Listen-In is a recently developed app utilising gamification principles, aimed at improving auditory comprehension for people with aphasia through easily accessible high doses of therapy. In a crossover, RCT participants (n = 35) completed 85 hours of self-managed therapy over 12 weeks (compared to usual care) practising over 800 words presented as single words and sentences (Fleming et al., Citation2020). Results revealed large and significant improvements for trained words and sentences with gains maintained at the 12 and 24 week follow-up.

Two major benefits of computer-based aphasia interventions are the opportunity to: (a) prescribe and enable much higher doses of interventions than can usually be provided by therapists in face-to-face clinician mediated intervention programs, and (b) enable self-managed practice at times and in places that may better suit the individual. However, other elements of computer-based therapy may be even more powerful than the high dose and self-management options already described. Application of sophisticated artificial intelligence (AI) to computer-based aphasia therapies will enable greater personalisation and diversity of therapy targets and activities, provision of feedback that is adjusted by user performance, and selection of therapy dose and timing that is titrated to an individual’s performance over time (Adikari et al., Citation2023). Our group is exploring AI applications in a large National Health and Medical Research Council funded project, Communication Connect, where we are codesigning community-level solutions with people living with aphasia and multidisciplinary health professionals, to manage aphasia across the life span (results expected in 2025). Such AI applications could render interventions far more effective than those currently provided face-to-face and would release clinicians to focus on more complex elements of aphasia management such as family counselling and psychological wellbeing, as discussed in the next section.

Way forward #3: There are interventions and approaches that can effectively address psychological wellbeing in people with aphasia—speech-language pathologists can play a vital role

Psychological wellbeing is significantly challenged in the context of aphasia, both for the person living with aphasia (Baker et al., Citation2018; Hilari, Citation2011; Hilari & Northcott, Citation2017; Kauhanen et al., Citation2000) but also for their family and friends (Johansson et al., Citation2022). Finding effective ways to support psychological wellbeing is an important element of aphasia management. However, speech-language pathologists report that they lack the confidence and skills to manage psychological wellbeing (Rose et al., Citation2014; Sekhon et al., Citation2015), while psychologists and other mental health professionals lack knowledge of aphasia and the communication skills to adapt their interventions to people who struggle to engage in talking-based psychological interventions (Ryan et al., Citation2020). One approach to address this gap in service provision is stepped psychological care (Kneebone, Citation2016). Stepped psychological care is a multidisciplinary model of care to address psychological problems after stroke including depression and anxiety. It is designed to be responsive to a person’s symptoms, recovery, and individual needs. In stepped psychological care, trained health professionals, including speech-language pathologists, deliver mood screening, counselling, and psychological therapy at lower, less intense levels of care while mental health professionals deliver psychological therapy at higher levels of care. In this way psychological care is everyone’s business in the health care team, with team members having very specific roles. There are a range of interventions at level 1 (subthreshold problems in mood) and level 2 (mild to moderate mood impairment) that speech-language pathologists can deliver independently or with support and supervision from a trained mental health practitioner.

One example of these interventions is solution focused brief therapy (SFBT), a psychological therapy that focuses on identifying and supporting an individual’s own expertise and resources to move positively forward with their aphasia. In a recent phase II pilot trial, Solution Focused Brief Therapy in Post-Stroke Aphasia (SOFIA; n = 32, including individuals with severe aphasia), Northcott et al. (Citation2021) investigated the feasibility and acceptability of up to 6 sessions of SFBT delivered by study trained speech-language pathologists over 3 months. Qualitative data from participants strongly support the intervention and preliminary results in this underpowered trial were positive on measures of mood. Another approach is peer-befriending (Hilari et al., Citation2021), where trained volunteers meet people with aphasia in their homes for up to 6 sessions to offer empathy, companionship, hope, and practical ways to cope with the impacts of aphasia. In a single-blinded parallel group pilot study, Supporting Wellbeing through Peer-Befriending (SUPERB; n = 56 people with aphasia; n = 48 significant others), Hilari et al. (Citation2021) investigated the feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy of their peer-befriending program. They found high levels of acceptability and lower levels of distress in the participants with aphasia following the program compared to the usual care control group. A third example of applying stepped psychological care is the Aphasia Prevention Intervention and Support in Mental health (PRISM) study (Baker et al., Citation2020). Aphasia PRISM involves the adaptation and testing of a menu of three evidence-based interventions delivered by trained speech-language pathologists and other allied health personnel to people with aphasia after stroke to support their psychological wellbeing: behavioural activation, relaxation therapy, and problem-solving therapy. Aphasia PRISM is currently in phase I trials in Victoria, Australia with results expected by the end of 2023.

A barrier to the implementation of stepped psychological care is a lack of knowledge, skills, and confidence to engage in counselling (Sekhon et al., Citation2015). To address this barrier Sekhon et al. (Citation2022) developed an online counselling education program (7 hours self-directed learning; 3-hour online workshop) and investigated the feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy of the program in a phase II RCT (n = 49). Participants found the program acceptable and there was a positive effect on participant self-efficacy and self-rated competence for counselling following the program and at 5 week follow-up.

Another approach to tackle the negative impacts of aphasia on psychological wellbeing is community aphasia groups (CAGs; Rose & Attard, Citation2015). CAGs involve a group of people with aphasia meeting, together with a facilitator, and offer opportunity for communication activity, emotional support, peer support, social activity, and education about stroke and aphasia. They are a place where realistic interventions can be enacted, ongoing monitoring of needs can occur, and they create opportunities to participate in meaningful and accessible activities. A challenge to the implementation of CAGs across Australia has been a lack of clinician knowledge, time, and implementation resources such as manuals and group resources (Rose & Attard Citation2015). The Inter-Disciplinary (InterD) CAG program was developed to address these implementation barriers (Attard et al., Citation2018). The InterD CAG is a 12 week, 2 hours per week, modularised program allowing group facilitators (speech-language pathologist and social worker) to discuss program options with group members (people with aphasia and their significant others) and allow them to choose the nature and structure of the program (for details, downloadable program manual, and implementation resources see: https://aphasia.community/resources/resources-for-aphasia-groups). Program modules include: stroke and aphasia education; communication skills practice; psychological support and identity work; social support; participation in nonverbal meaningful and enjoyable activities such as photography, art, yoga, and music; conversation activity; and a carer support program. A phase I proof of concept study involving four participants with severe aphasia and their spouses showed clinically meaningful change on functional communication, communication confidence, and social networks for three participants (Attard et al., Citation2018). A recent extension and possibly more economically viable model of the InterD CAG is the peer-led Hub-and-Spoke CAG. In this model, the same InterD CAG program options are utilised but the health professionals (the Hub) train volunteers and people with mild or recovered aphasia to be the CAG facilitators (Spokes), freeing up the health professionals to train facilitators, refer their patients, and be available to support facilitators as challenges arise. This model is currently undergoing preliminary testing embedded within the Grampians Health Community Rehabilitation service in Victoria.

One barrier to speech-language pathologists being involved in long-term care models such as CAGs is the funding models underpinning rehabilitation and community health care. These models often prohibit clinicians from engaging with clients beyond small periods of highly defined service and may not allow for regular review or re-entry to service. This barrier is addressed in the next section.

Way forward #4: There are comprehensive models of care that can address multiple goals in effective doses, even in the chronic phase of recovery

One option for delivering therapy in both a high and intensive dose while simultaneously addressing goals across the ICF, are intensive comprehensive aphasia programs (ICAPs; Rose et al., Citation2013). ICAPs were first described in 2013 and are defined as: high intensity (at least 3 hours/day over 2+ weeks); using a mix of group and individual therapy; targeting communication impairment, activity and participation, and environmental factors across the ICF; involving education and support for the individual and the family; and having the overarching goals of maximising communication and life participation (Rose et al., Citation2013). A recent international survey (Rose et al., Citation2022) demonstrated 21 ICAPs running across the world (the USA, Canada, Australia, and the UK), 13 of which were new since the original 2013 survey. Several studies utilising a range of different ICAP program options have demonstrated efficacy of ICAPs (medium to large effects sizes) on naming and overall aphasia severity, communication participation, communication confidence, quality of life, and mood (total n = 284 across all studies; Babbitt et al., Citation2015; Dignam et al., Citation2015; Griffin-Musick et al., Citation2021; Hoover et al., Citation2017; Leff et al., Citation2021; Winans-Mitrik et al., Citation2014), with some studies showing strong maintenance of effects (Babbitt et al., Citation2015; Leff et al., Citation2021; Winans-Mitrik et al., Citation2014). To date, ICAPs have generally been delivered as face-to-face intervention but recently the Queensland Aphasia Research Centre has been trialling a telehealth version of the comprehensive high dose aphasia therapy (CHAT) with promising early results (publications forthcoming). ICAPs may well be a more effective and efficient service delivery model than many current low dose, low intensity, and short-term services. Comparative and cost effectiveness evidence is yet to be produced, but the effect sizes and maintenance of effects from ICAPs to date are extremely promising. If the evidence favouring ICAPs becomes available, how will speech-language pathologists mount these services within current service restrictions?

A barrier to the implementation of ICAPs in Australia and many countries around the world is the strong focus on healthcare and rehabilitation for aphasia within the first few months after stroke, and the inevitable discharge to minimal or no services after this short period. This is occurring despite strong evidence to support the long-term nature of aphasia and its broad and evolving impacts across all areas of life (Davidson et al., Citation2008; El Hachioui et al., Citation2013; Engelter et al., Citation2006; Hilari & Northcott, Citation2017; Lam & Wodchis, Citation2010; Shadden, Citation2005). It is time for aphasia to be more accurately viewed as a chronic condition, and for planning and service delivery to be situated within a model of chronic health management. Australia has a well-developed national strategic framework for chronic conditions (Australian Council of Governments, Citation2017) to support the development of appropriate long-term services and support for chronic health conditions. For example, diabetes care is strongly situated within a model of chronic care; however, this has not been adequately applied to aphasia management. There has been a lack of attention to the development of self-management strategies, a failure to offer review or service re-entry opportunities, and a lack of attention to the important role for speech-language pathologists in coordinating care for people living with aphasia and their families (Nichol et al., Citation2023). Examples of speech-language pathologists successfully challenging professional boundaries were reported in qualitative interviews by Trebilcock and colleagues (Citation2021). These speech-language pathologists described the need to develop strategic partnerships across healthcare systems, to involve consumer advocacy groups, and to partner with researchers to tackle system-level barriers, develop more appropriate service options that met the needs of their clients, and improve overall aphasia management.

Conclusion

There is high level evidence that aphasia therapy works when provided in sufficient dose and intensity, and it is likely that maintenance doses support longer term maintenance of gains from these therapy approaches. However, usual care is generally delivered in doses that are unlikely to be effective and needs urgent revision. The overemphasis on care within the first 3 months post-stroke fails to adequately address the chronic nature of aphasia and people’s changing communicative needs across time. There is a need to consider models of chronic health management, including options for long-term support, service re-entry, and better self-management strategies to better manage the reality of aphasia as a chronic condition. Such challenges to practice are likely to be more successful when supported by strategic partnerships across health sectors, consumer advocacy groups, and researchers. Aphasia management requires a biopsychosocial approach to address the negative impacts of aphasia on psychosocial wellbeing, families, and friends. Speech-language pathologists, together with their mental health colleagues, have an important role to play in supporting psychosocial wellbeing and preventing the development of depression and anxiety in people with aphasia and their families/carers. Therapy delivered via computers, via trained assistants, and in groups is effective and less costly than face-to-face and clinician-led options for many people with aphasia. Rapid developments in technology offer the opportunity for more effective interventions and efficiencies in service delivery, leading to a reprioritising of speech-language pathology roles and focus. For many speech-language pathologists, this will require an expanded scope of practice involving mental health care, care coordination and consultative roles, and expertise in technology applications. It is time for implementation!

Acknowledgements

Sincere thanks to my many national and international collaborators, PhD students, and research staff whose work has stimulated my thinking in the themes discussed in this manuscript, and to all those people with aphasia and their care partners who have challenged and informed my practice since my first professional encounters in 1978.

Disclosure statement

The author reports no declarations of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adikari, A., Hernandez, N., Alahakoon, D., Rose, M. L., & Pierce, J. (2023). From concept to practice: A scoping review of the application of AI to aphasia diagnosis and management. Disability and Rehabilitation, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2023.2199463

- Australian Council of Governments. (2017). National Strategic Framework for Chronic Conditions.

- Attard, M. C., Loupis, Y., Togher, L., & Rose, M. L. (2018). The efficacy of an inter-disciplinary community aphasia group for living well with aphasia. Aphasiology, 32(2), 105–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2017.1381877

- Babbitt, E. M., Worrall, L., & Cherney, L. R. (2015). Structure, processes, and retrospective outcomes from an intensive comprehensive aphasia program. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 24(4), S854–S863. https://doi.org/10.1044/2015_AJSLP-14-0164

- Baker, C., Worrall, L., Rose, M., Hudson, K., Ryan, B., & O'Byrne, L. (2018). A systematic review of rehabilitation interventions to effectively prevent and treat depression in post-stroke aphasia. Disability and Rehabilitation, 40(16), 1870–1892. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2017.1315181

- Baker, C., Worrall, L., Rose, M., & Ryan, B. (2020). It was really dark: The experiences and preferences of people with aphasia to manage mood changes and depression. Aphasiology, 34(1), 19–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2019.1673304

- Bartlett, G., Blais, R., Tamblyn, R., Clermont, R. J., & MacGibbon, B. (2008). Impact of patient communication problems on the risk of preventable adverse events in acute care settings. Canadian Medical Association Journal = Journal de L'Association Medicale Canadienne, 178(12), 1555–1562. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.070690

- Brady, M. C., Kelly, H., Godwin, J., Enderby, P., & Campbell, P. (2016). Speech and language therapy for aphasia following stroke. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2016(6), CD000425. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD000425.pub4

- Brady, M. C., Ali, M., VandenBerg, K., Williams, L. J., Williams, L. R., Abo, M., Becker, F., Bowen, A., Brandenburg, C., Breitenstein, C., Bruehl, S., Copland, D. A., Cranfill, T. B., di Pietro-Bachmann, M., Enderby, P., Fillingham, J., Galli, F. L., Gandolfi, M., Glize, B., … Wright, H. H (2022a). Dosage, intensity and frequency of language therapy for aphasia: An individual participant data network meta-analysis. Stroke, 53(3), 956–967. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.121.035216

- Brady, M. C., Ali, M., VandenBerg, K., Williams, L. J., Williams, L. R., Abo, M., Becker, F., Bowen, A., Brandenburg, C., Breitenstein, C., Bruehl, S., Copland, D. A., Cranfill, T. B., Pietro-Bachmann, M. d., Enderby, P., Fillingham, J., Lucia Galli, F., Gandolfi, M., Glize, B., … Harris Wright, H., (2022b). Precision rehabilitation for aphasia by patient age, sex, aphasia severity, and time since stroke? A prespecified, systematic review-based, individual participant data, network, subgroup meta-analysis. International Journal of Stroke : Official Journal of the International Stroke Society, 17(10), 1067–1077. https://doi.org/10.1177/17474930221097477

- Breitenstein, C., Grewe, T., Flöel, A., Ziegler, W., Springer, L., Martus, P., Huber, W., Willmes, K., Ringelstein, E. B., Haeusler, K. G., Abel, S., Glindemann, R., Domahs, F., Regenbrecht, F., Schlenck, K.-J., Thomas, M., Obrig, H., de Langen, E., Rocker, R., … Baumgaertner, A., (2017). Intensive speech and language therapy in patients with chronic aphasia after stroke: A randomised, open-label, blinded-endpoint, controlled trial in a health-care setting. Lancet, 389(10078), 1528–1538. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30067-3

- Brogan, E., Kim, J., Grimley, R., Wallace, S., Baker, C., Thayabaranathan, T., Andrew, N., Kilkenny, M., Godecke, E., Rose, M., & Cadilhac, D. (2022). The excess costs of hospitalization for acute stroke in people with communication impairment: a Stroke123 data linkage substudy. Archives Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 104(6), 42-949. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2023.01.015

- Carragher, M., Steel, G., Talbot, R., Devane, N., Rose, M. L., & Marshall, J. (2021). Adapting therapy for a new world: Storytelling therapy in EVA park. Aphasiology, 35(5), 704–729. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2020.1812249

- Corsten, S., Konradi, J., Schimpf, E. J., Hardering, F., & Keilmann, A. (2014). Improving quality of life in aphasia—Evidence for the effectiveness of the biographic-narrative approach. Aphasiology, 28(4), 440–452. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2013.843154

- Corsten, S., Schimpf, E. J., Konradi, J., Keilmann, A., & Hardering, F. (2015). The participants’ perspective: How biographic-narrative intervention influences identity negotiation and quality of life in aphasia. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 50(6), 788–800. https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12173

- Davidson, B., Howe, T., Worrall, L., Hickson, L., & Togher, L. (2008). Social participation for older people with aphasia: The impact of communication disability on friendships. Topics in Stroke Rehabilitation, 15(4), 325–340. https://doi.org/10.1310/tsr1504-325

- Deloitte Access Economics. (2020). The economic impact of stroke in Australia, 2020. Stroke Foundation.

- Denham, A. M. J., Wynne, O., Baker, A. L., Spratt, N. J., Loh, M., Turner, A., Magin, P., & Bonevski, B. (2022). The long-term unmet needs of informal carers of stroke survivors at home: A systematic review of qualitative and quantitative studies. Disability and Rehabilitation, 44(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2020.1756470

- Dignam, J., Copland, D., McKinnon, E., Burfein, P., O'Brien, K., Farrell, A., & Rodriguez, A. D. (2015). Intensive versus distributed aphasia therapy: A nonrandomized, parallel-group, dosage-controlled study. Stroke, 46(8), 2206–2211. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.009522

- D'Souza, S., Godecke, E., Ciccone, N., Hersh, D., Janssen, H., & Armstrong, E. (2021). Hospital staff, volunteers’ and patients’ perceptions of barriers and facilitators to communication following stroke in an acute and a rehabilitation private hospital ward: A qualitative description study. BMJ Open, 11(5), e043897. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-043897

- El Hachioui, H., Lingsma, H. F., Van De Sandt-Koenderman, M. W. M. E., Dippel, D. W. J., Koudstaal, P. J., & Visch-Brink, E. G. (2013). Long-term prognosis of aphasia after stroke. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry, 84(3), 310–315. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2012-302596

- Engel, G. L. (1977). The need for a new medical model: A challenge for biomedicine. Science (New York, N.Y.), 196(4286), 129–136. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.847460

- Engelter, S. T., Gostynski, M., Papa, S., Frei, M., Born, C., Ajdacic-Gross, V., Gutzwiller, F., & Lyrer, P. A. (2006). Epidemiology of aphasia attributable to first ischemic stroke: Incidence, severity, fluency, etiology, and thrombolysis. Stroke, 37(6), 1379–1384. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.STR.0000221815.64093.8c

- Fleming, V., Brownsett, S., Krason, A., Maegli, M. A., Coley-Fisher, H., Ong, Y.-H., Nardo, D., Leach, R., Howard, D., Robson, H., Warburton, E., Ashburner, J., Price, C. J., Crinion, J. T., & Leff, A. P. (2020). Efficacy of spoken word comprehension therapy in patients with chronic aphasia: A cross-over randomised controlled trial with structural imaging. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry, 92(4), 418–424. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2020-324256

- Foster, A. M., Worrall, L. E., Rose, M. L., & O'Halloran, R. (2016a). I do the best I can’: An in-depth exploration of the aphasia management pathway in the acute hospital setting. Disability and Rehabilitation, 38(18), 1765–1779. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2015.1107766

- Foster, A., O'Halloran, R., Rose, M., & Worrall, L. (2016b). Communication’s taking a back seat’: Speech-language pathologists’ perceptions of aphasia management in acute hospital settings. Aphasiology, 30(5), 585–608. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2014.985185

- Grawburg, M., Howe, T., Worrall, L., & Scarinci, N. (2013). A qualitative investigation into third-party functioning and third-party disability in aphasia: Positive and negative experiences of family members of people with aphasia. Aphasiology, 27(7), 828–848. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2013.768330

- Griffin-Musick, J. R., Off, C. A., Milman, L., Kincheloe, H., & Kozlowski, A. (2021). The impact of a university-based intensive comprehensive aphasia program (ICAP) on psychosocial well-being in stroke survivors with aphasia. Aphasiology, 35(10), 1363–1389. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2020.1814949

- Grimley, R. S., Rosbergen, I. C., Gustafsson, L., Horton, E., Green, T., Cadigan, G., Kuys, S., Andrew, N. E., & Cadilhac, D. A. (2020). Dose and setting of rehabilitation received after stroke in Queensland, Australia: A prospective cohort study. Clinical Rehabilitation, 34(6), 812–823. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215520916899

- Guyatt, G. H., Oxman, A. D., Vist, G. E., Kunz, R., Falck-Ytter, Y., Alonso-Coello, P., & Schünemann, H. J. (2008). GRADE: An emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. British Medical Journal (Clinical Research Ed.), 336(7650), 924–926. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD

- Hilari, K., Northcott, S., Roy, P., Marshall, J., Wiggins, R. D., Chataway, J., & Ames, D. (2010). Psychological distress after stroke and aphasia: The first six months. Clinical Rehabilitation, 24(2), 181–190. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215509346090

- Hilari, K. (2011). The impact of stroke: are people with aphasia different to those without? Disability and Rehabilitation, 33(3), 211–218. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2010.508829

- Hilari, K., & Northcott, S. (2017). Struggling to stay connected’: Comparing the social relationships of healthy older people and people with stroke and aphasia. Aphasiology, 31(6), 674–687. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2016.1218436

- Hilari, K., Behn, N., James, K., Northcott, S., Marshall, J., Thomas, S., Simpson, A., Moss, B., Flood, C., McVicker, S., & Goldsmith, K. (2021). Supporting wellbeing through peer-befriending (SUPERB) for people with aphasia: A feasibility randomised controlled trial. Clinical Rehabilitation, 35(8), 1151–1163. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215521995671

- Holland, A., Frattali, C., & Fromm, D. (1999). Communication Activities of Daily Living (CADL-2). (2nd ed). Pro-Ed.

- Hoover, E. L., Caplan, D. N., Waters, G. S., & Carney, A. (2017). Communication and quality of life outcomes from an interprofessional intensive, comprehensive, aphasia program (ICAP). Topics in Stroke Rehabilitation, 24(2), 82–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/10749357.2016.1207147

- Johansson, M., Carlsson, M., Ostberg, P., & Sonnander, K. (2022). Self-reported changes in everyday life and health of significant others with aphasia: a quantitative approach. Aphasiology, 36(1), 76–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2020.1852166

- Kagan, A., Simmons-Mackie, N., Rowland, A., Huijbregts, M., Shumway, E., McEwen, S., Threats, T., & Sharp, S. (2008). Counting what counts: A framework for capturing real-life outcomes of aphasia intervention. Aphasiology, 22(3), 258–280. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687030701282595

- Kauhanen, M.-L., Korpelainen, J., Hiltunen, P., Määttä, R., Mononen, H., Brusin, E., Sotaniemi, K., & Myllylä, V. (2000). Aphasia, depression, and non-verbal cognitive impairment in ischaemic stroke. Cerebrovascular Diseases , 10(6), 455–461. https://doi.org/10.1159/000016107

- Kneebone, I. (2016). Stepped psychological care after stroke. Disability and Rehabilitation, 38(18), 1836–1843. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2015.1107764

- Lam, J. M., & Wodchis, W. P. (2010). The relationship of 60 disease diagnoses and 15 conditions to preference-based health-related quality of life in Ontario hospital-based long-term care residents. Medical Care, 48(4), 380–387. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181ca2647

- Leff, A. P., Nightingale, S., Gooding, B., Rutter, J., Craven, N., Peart, M., Dunstan, A., Sherman, A., Paget, A., Duncan, M., Davidson, J., Kumar, N., Farrington-Douglas, C., Julien, C., & Crinion, J. T. (2021). Clinical effectiveness of the Queen Square Intensive comprehensive aphasia service for patients with poststroke aphasia. Stroke, 52(10), e594-e598. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.033837

- Marshall, J., Devane, N., Edmonds, L., Talbot, R., Wilson, S., Woolf, C., & Zwart, N. (2018). Delivering word retrieval therapies for people with aphasia in a virtual communication environment. Aphasiology, 32(9), 1054–1074. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2018.1488237

- Marshall, J., Devane, N., Talbot, R., Caute, A., Cruice, M., Hilari, K., MacKenzie, G., Maguire, K., Patel, A., Roper, A., & Wilson, S. (2020). A randomised trial of social support group intervention for people with aphasia: A Novel application of virtual reality. Plos One, 15(9), e0239715. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239715

- Menahemi-Falkov, M., Breitenstein, C., Pierce, J. E., Hill, A. J., O'Halloran, R., & Rose, M. L. (2022). A systematic review of maintenance following intensive therapy programs in chronic aphasia: Importance of individual response analysis. Disability and Rehabilitation, 44(20), 5811–5826. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2021.1955303

- Mitchell, A. J., Sheth, B., Gill, J., Yadegarfar, M., Stubbs, B., Yadegarfar, M., & Meader, N. (2017). Prevalence and predictors of post-stroke mood disorders: A meta-analysis and meta- regression of depression, anxiety and adjustment disorder. General Hospital Psychiatry, 47, 48–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2017.04.001

- Morris, R., Eccles, A., Ryan, B., & Kneebone, I. (2017). Prevalence of anxiety in people with aphasia after stroke. Aphasiology, 31(12), 1410–1415. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2017.1304633

- Nichol, L., Rodriguez, A. D., Pitt, R., Wallace, S. J., & Hill, A. J. (2023). Self-management has to be the way of the future’ Exploring the perspectives of speech-language pathologists who work with people with aphasia. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 25(2), 327–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/17549507.2022.2055144

- Northcott, S., Thomas, S., James, K., Simpson, A., Hirani, S., Barnard, R., & Hilari, K. (2021). Solution focused brief therapy in post-stroke Aphasia (SOFIA): Feasibility and acceptability results of a feasibility randomised wait-list controlled trial. BMJ Open, 11(8), e050308. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-050308

- Palmer, R., Witts, H., & Chater, T. (2018). What speech and language therapy do community dwelling stroke survivors with aphasia receive in the UK? PLoS One, 13(7), e0200096. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0200096

- Palmer, R., Dimairo, M., Cooper, C., Enderby, P., Brady, M., Bowen, A., Latimer, N., Julious, S., Cross, E., Alshreef, A., Harrison, M., Bradley, E., Witts, H., & Chater, T. (2019). Self-managed, computerised speech and language therapy for patients with chronic aphasia post-stroke compared with usual care or attention control (Big CACTUS): a multicentre, single-blinded, randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. Neurology, 18(9), 821–833. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30192-9

- Pierce, J. E., OHalloran, R., Togher, L., Nickels, L., Copland, D., Godecke, E., Meinzer, M., Rai, T., Cadilhac, D. a., Kim, J., Hurley, M., Foster, A., Carragher, M., Wilcox, C., Steel, G., & Rose, M. L. (2023). Acceptability, feasibility and preliminary efficacy of low-moderate intensity Constraint Induced Aphasia Therapy and Multi-Modality Aphasia Therapy in chronic aphasia after stroke. Topics in Stroke Rehabilitation, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/10749357.2023.2196765

- Rose, M., Cherney, L., & Worrall, L. (2013). Intensive comprehensive aphasia rehabilitation programs (ICAPs): An international survey of practice. Topics in Stroke Rehabilitation, 20(5), 379–387. https://doi.org/10.1310/tsr2005-379

- Rose, M., Ferguson, A., Power, E., Togher, L., & Worrall, L. (2014). Aphasia rehabilitation in Australia: Current practices, challenges and future directions. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 16(2), 169–180. https://doi.org/10.3109/17549507.2013.794474

- Rose, M., & Attard, M. (2015). Practices and challenges in community aphasia groups in Australia: Results of a national survey. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 17(3), 241–251. https://doi.org/10.3109/17549507.2015.1010582

- Rose, M., Pierce, J., Scharp, T., Off, C., Griffin, J., & Babbitt, E., & Cherney, L. (2022a). Developments in the application of Intensive Comprehensive Aphasia Programs: An international survey of practice. Disability and Rehabilitation, 44(20), 5863–5877. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2021.1948621

- Rose, M., Nickels, L., Copland, D., Togher, L., Godecke, E., Meinzer, M., Rai, T., Cadilhac, D., Kim, J., Hurley, M., Foster, A., Carragher, M., Wilcox, C., Pierce, J., & Steel, G. (2022b). Results of the COMPARE trial of constraint induced or multi-modality aphasia therapy in chronic post-stroke aphasia. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 93 (6), 573–581. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2021-328422

- Ryan, B., Worrall, L., Sekhon, J., Baker, C., Carragher, M., Bohan, J., Power, E., Rose, M., Simmons-Mackie, N., Togher, L., & Kneebone, I. (2020). Time to step up: A call to the speech pathology profession to utilise stepped psychological care for people with aphasia post stroke. In Meredith, K. and G. Yeates (Eds.), Psychotherapy and Aphasia: Interventions for Emotional Wellbeing and Relationships. (Chapter 1, 1–14). Routledge.

- Sekhon, J., Douglas, J., & Rose, M. (2015). Current Australian speech-language pathology practice in addressing psychological wellbeing in people with aphasia after stroke. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 17(3), 252–262. https://doi.org/10.3109/17549507.2015.1024170

- Sekhon, J., Oates, J., Kneebone, I., & Rose, M. (2022). A phase II randomised controlled trial evaluating the feasibility and preliminary efficacy of an education program on speech-language pathologist’ self-efficacy, and self-rated competency for counselling to support psychological wellbeing in people with post-stroke aphasia. Topics in Stroke Rehabilitation, 28, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/10749357.2022.2145736

- Shadden, B. (2005). Aphasia as identity theft: Theory and practice. Aphasiology, 19(3–5), 211–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687930444000697

- Simmons-Mackie, N., Raymer, S., & Cherney, L. (2016). Communication partner training in aphasia: An updated systematic review. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 97(12), 2202–2221.e8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2016.03.023

- Simmons-Mackie, N., Worrall, L., Murray, L. L., Enderby, P., Rose, M. L., Paek, E. J., & Klippi, A. (2017). The top ten best practice recommendations for aphasia. Aphasiology, 31(2), 131–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2016.1180662

- Stroke Foundation. (2020). National Stroke Audit -Rehabilitation Services Report Melbourne.

- Sullivan, R., & Harding, K. (2019). Do patients with severe poststroke communication difficulties have a higher incidence of falls during inpatient rehabilitation? A retrospective cohort study. Topics in Stroke Rehabilitation, 26(4), 288–293. https://doi.org/10.1080/10749357.2019.1591689

- Thayabaranathan, T., Baker, C., Andrew, N. E., Stolwyk, R., Thrift, A. G., Carter, H., Moss, K., Kim, J., Wallace, S. J., Brogan, E., Grimley, R., Lannin, N. A., Rose, M. L., & Cadilhac, D. A. (2022). Exploring dimensions of quality of life in stroke survivors with communication disabilities- a brief report. Topics in Stroke Rehabilitation, 4, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/10749357.2022.2095087

- Trebilcock, M., Worrall, L., Ryan, B., Shrubsole, K., Jagoe, C., Simmons-Mackie, N., Bright, F., Cruice, M., Pritchard, M., & Le Dorze, G. (2019). Increasing the intensity and comprehensiveness of aphasia services: Identification of key factors influencing implementation across six countries. Aphasiology, 33(7), 865–887. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2019.1602860

- Verna, A., Davidson, B., & Rose, T. (2009). Speech-language pathology services for people with aphasia: A survey of current practice in Australia. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 11(3), 191–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/17549500902726059

- Vickers, C. P. (2010). Social networks after the onset of aphasia: The impact of aphasia group attendance. Aphasiology, 24(6–8), 902–913. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687030903438532

- Winans-Mitrik, R. L., Hula, W. D., Dickey, M. W., Schumacher, J. G., Swoyer, B., & Doyle, P. J. (2014). Description of an intensive residential aphasia treatment program: Rationale, clinical processes, and outcomes. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 23(2), S330–S342. https://doi.org/10.1044/2014_AJSLP-13-0102

- World Health Organisation (WHO). (2001). International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health: ICF. World Health Organization.