Abstract

Purpose

Treatment for oral cancer has debilitating effects on speech and swallowing, however, little is known about current speech-language pathology practice.

Method

An online survey of speech-language pathologists (SLPs) was disseminated via emails to speech pathology departments, social media platforms, and professional online forums. Survey questions captured demographics, service delivery, type and timing of speech and swallowing interventions, and influences and barriers to practice.

Result

Forty-three SLPs working in Australia (n = 41) and New Zealand (n = 2) completed the survey. SLPs recommended speech and swallowing compensatory strategies significantly more frequently than active intervention. Swallowing outcomes measures were either instrumental (n = 31, 94%) or performance ratings (n = 25, 76%), whereas speech was measured informally with judgements of intelligibility (n = 30, 91%). SLPs used a range of supports for their decision making, particularly expert opinion (n = 81, 38.2%). They reported time and staffing limitations (n = 55, 55%) and a lack of relevant evidence (n = 35, 35%) as the largest barriers to evidence-based service delivery.

Conclusion

There is variability amongst SLPs in Australia and New Zealand regarding rehabilitation of speech and swallowing for people with oral cancer. This study highlights the need for evidence-based guidelines outlining best practice for screening processes, active rehabilitation protocols, and valid outcome measures with this population.

Introduction

Oral cancer and the treatments used to cure it have debilitating effects on both speech and swallowing in daily life (Kreeft et al., Citation2009; Pauloski et al., Citation2000; Riemann et al., Citation2016). Dysfunction in either speech or swallowing in these patients has a number of causes, including pain or structural changes caused by the tumour itself (Colangelo et al., Citation2000; Lango et al., Citation2014); from surgical removal of the lesion and/or subsequent tissue reconstruction (Kreeft et al., Citation2009); or from chemoradiation therapy as a curative intervention (Baudelet et al., Citation2019; Kalavrezos et al., Citation2014; Stelzle et al., Citation2013). All of these factors, and combinations of them, cause reduced speech accuracy and clarity (Balaguer et al., Citation2020; Suarez-Cunqueiro et al., Citation2008) and a reduction in the ability to move food or fluid safely and efficiently through the oral cavity (Kalavrezos et al., Citation2014). Such changes in speech and swallowing not only impact everyday functioning following oral cancer, but also have a negative impact on quality of life (Nund et al., Citation2014; Nund et al., Citation2015).

Oral cancers of the lips, mouth, and tongue made up 51% of all new Australian head and neck cancer (HNC) diagnoses in 2021 (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Citation2021a) and 46% of New Zealand HNC registrations in 2019 (Ministry of Health, Citation2021). The 5 year survival rate for people with oral cancer continues to be high in Australia compared to other HNC groups (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Citation2021b), meaning that many people with oral cancer are living with potentially chronic and debilitating speech and/or swallow dysfunction.

Considering the established presence of dysfunction and the negative impact on survivorship which results from HNC, speech-language pathology intervention for both speech and swallowing are required to optimise function and facilitate social participation. Unfortunately, to date, there is a paucity of evidence and guidance for speech-language pathologists (SLPs) providing these interventions—specifically for people with oral cancer, but also more generally amongst the HNC population.

There are no published guidelines in Australia focused on management of communication and swallowing following HNC. Additionally, little advice is available internationally, for example, guidelines from the UK (National Institute for Clinical Excellence, Citation2004) report the importance of speech-language pathology involvement across the HNC treatment journey, however, they do not describe or recommend specific speech-language pathology interventions.

Multidiscpinary HNC management guidelines have been published in the UK (Paleri & Roland, Citation2016) with Clarke et al. (Citation2016) publishing speech and swallowing management guidelines for SLPs. These guidelines focus on service provision and highlight the importance of assessment before cancer treatment and swallowing intervention following treatment. Unfortunately, speech interventions and interventions specific to people with oral cancer were not specified. Additionally, intervention dosages and duration of follow-up were not described. Similarly, a service framework for US SLPs treating people with oral cancer (Arrese & Hutcheson, Citation2018) outlined speech and swallowing deficits following cancer treatments, the benefit of proactive intervention, and considerations for rehabilitation. However, these authors also did not provide guidance with specific interventions, dosage, or follow-up.

A scoping review of the rehabilitation provided to HNC survivors (Rodriguez et al., Citation2019) reported that 14 of the 39 included papers included swallowing outcomes, whereas only one paper reported communication outcomes (voice). More specific to oral cancer, a systematic review of intervention following partial glossectomy found seven studies with only one publication reporting on both speech and swallowing functions (Blyth et al., Citation2015). Many of the reviewed papers reported use of concurrent speech and/or swallowing interventions along with inconsistent use of outcome measures, making it difficult to translate findings to clinical practice.

Considering the lack of clinical guidance and the paucity of evidence, particularly for speech intervention, there is a risk that SLPs are providing suboptimal speech and swallowing management for people with oral cancer. In the absence of robust evidence to guide practice, SLPs are encouraged to benchmark their services against that of others (Enderby, Citation2017). To date, several speech-language pathology HNC benchmarking surveys have been published in Australia (Lawson et al., Citation2017), the USA (Krisciunas et al., Citation2012; Logan & Landera, Citation2021), and the UK (Roe et al., Citation2012). All have investigated speech-language pathology practices for swallowing management amongst people with a wide range of HNCs, rather than oral cancer specifically. Considering that the severity of speech and swallowing dysfunction is specific to the site of cancer (Denaro et al., Citation2013; Jacobi et al., Citation2013), along with the importance of the oral cavity to both speech articulation and the oral swallowing phase (Kolokythas, Citation2010), research ideally should include both speech and swallowing functions as well as specifically report oral cancer as a distinct HNC group. There are no published benchmarks of speech-language pathology services specifically amongst people undergoing oral cancer treatments. We, therefore, aimed to do this.

We sought to provide an understanding of speech and swallowing rehabilitation provided by Australian and New Zealand SLPs to people undergoing oral cancer treatment. We hypothesised that:

Patients undergoing cancer treatment to the tongue, palate, and floor of mouth will be more likely to receive speech-language pathology intervention, compared to those with cancer of the buccal cavity or gums, due to the increased speech and swallow dysfunction caused by alteration to these sites (Kreeft et al., Citation2009).

Interventions for swallowing dysfunction will more likely be prioritised over interventions for speech, due to the tendency for speech-language pathology services within acute care settings to prioritise swallowing over communication intervention (Foster et al., Citation2016).

SLPs will be more likely to recommend compensatory strategies than active rehabilitation due to a lack of high-level evidence regarding active rehabilitation for speech and swallowing functions (Blyth et al., Citation2015).

Considering research showing that when evidence is low, SLPs hybridise interventions (e.g. Chan et al., Citation2013; Gomez et al., Citation2022; Joffe & Pring, Citation2008), we hypothesised that SLPs will recommend interventions concurrently (two or more) with varied intensity.

Method

Ethical approval was obtained from The University of Sydney Human Ethics Committee (2018/139). All participants provided informed consent.

Survey development and questions

This study was an anonymous online survey using Qualtrics software. Questions were based on previous HNC survey literature (Krisciunas et al., Citation2012; Lawson et al., Citation2017). Further questions were included by KB and PM to enable investigation of the study aims. These questions related to speech assessment and rehabilitation practices, influences on SLPs’ choice of intervention, outcome measures used, discharge criteria, and service barriers experienced by SLPs (Blyth et al., Citation2014; Chan et al., Citation2013).

The survey contained 39 questions in a range of formats including Likert and numerical sliding scales, multiple answer, matrix tables, and free text to capture meaningful data efficiently amongst SLPs. Skip and display logic was used to enable participant progression through the survey relative to their previous responses. This meant SLPs only needed to respond to relevant survey questions, hence, the frequency of n across our results varies. Completion of the survey took less than 15 minutes. Survey questions were grouped into five sections requesting information about (a) clinician demographics and caseload, (b) service delivery, (c) speech and swallowing interventions, (d) influences on practice, and (e) service barriers experienced. See the appendix for survey questions.

The survey was piloted by an SLP with 2 years’ experience in HNC who was blinded to the project. Pilot feedback included minor edits to wording and spelling consistency across the survey, as well as question sequencing. These pilot responses were not included in our results, nor was the pilot SLP recruited to the study.

Recruitment

Qualified SLPs providing HNC services at the time of the survey or within the previous 12 months were invited to complete the survey. Invitations were disseminated via (a) the Australia and New Zealand Speech Pathology Head and Neck Google Group via a moderator, (b) direct emails to public Australian hospital speech therapy departments, and (c) online social networks. The survey was open for 5 months from April to September 2018, with participation reminders in August 2018.

Data analysis

Survey data was collected within Qualtrics and exported to Excel for descriptive interpretation and SPSS for statistical analysis. Data was categorical, including both nominal (e.g. work setting) and ordinal data (e.g. all, most, some, none). Descriptive statistics were used to describe frequencies of responses. Non-parametric analyses—Friedman and Wilcoxon signed-rank tests—were used to determine statistically significant differences and ranking of interventions selected for either speech or swallowing dysfunction. Kendall’s coefficient of concordance was used post hoc to determine effect size (W) and agreement of interventions selected by SLPs. Effect size of 0.1 to 0.3 was considered small, 0.3 to 0.5 medium, and >0.5 as large (Levin & Fox, Citation2006).

Chi-square test and Spearman’s correlation were used to investigate potential relationships between demographic variables (e.g. years working as an SLP or within HNC, clinical setting) compared to swallowing or speech intervention variables (e.g. type and frequency, outcome measures).

Result

Clinician demographics and caseload

Forty-three surveys were completed by SLPs working in Australia (n = 41) and New Zealand (n = 2). The cohort of New Zealand SLPs was too small to analyse separately, so were combined with Australian SLP responses. Most worked within tertiary teaching hospitals (39.5%, n = 17), had more than 10 years of experience working both as an SLP (65.1%, n = 28) and within HNC (39.5%, n = 17). They reported seeing patients with oral tongue (35%, n = 36) and floor of mouth cancers (32%, n = 33) most frequently and that surgical removal in combination with chemoradiotherapy was the most frequent (88%, n = 38) cancer treatment used in their work setting. Demographic, workplace, and caseload data are summarised in .

Table I. Clinician demographic and caseload information.

Referral and timing of intervention

Speech-language pathology services for swallowing were commonly initiated when patients self-reported difficulties (45.5%, n = 25) or following referral from HNC multidisciplinary team members (31%, n = 17). SLPs also reported initiating swallowing services regardless of referral (23.6%, n = 13). Services for speech were more frequently initiated when patients self-reported difficulties (70.2%, n = 33) compared to multidisciplinary referral (21.2%, n = 10). Very few clinicians (12%, n = 4) provided speech services to patients regardless of referral.

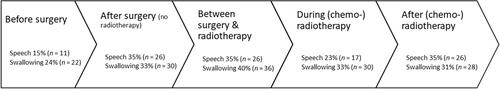

Most SLPs (40%, n = 36) reported initiating swallow intervention between surgery and (chemo-) radiotherapy whereas there was no preferred timing to commence interventions for speech. demonstrates when SLPs commence both speech and swallowing interventions across the cancer treatment timeline—before or after surgery, and before, during, or after (chemo-) radiotherapy.

Speech and swallowing interventions

SLPs indicated the type and frequency of interventions they recommend to people with oral cancers located within the gums, cheek, oral tongue, floor of mouth, soft palate, or hard palate. More SLPs selected interventions for people with oral tongue (n = 28) or floor of mouth (n = 25) cancers compared to those with soft palate (n = 7) or cheek, gum, or hard palate (n = 15) cancers. Following further analysis, SLP responses across the six oral cancer sites were combined due to few responses within each category. The range of speech and swallowing interventions were also grouped for analysis into four categories: (a) compensatory strategies, (b) active rehabilitation, (c) stretch or range of movement tasks, and (d) other therapies (option only for swallowing). Examples of these are outlined in .

Table II. Speech and swallowing interventions.

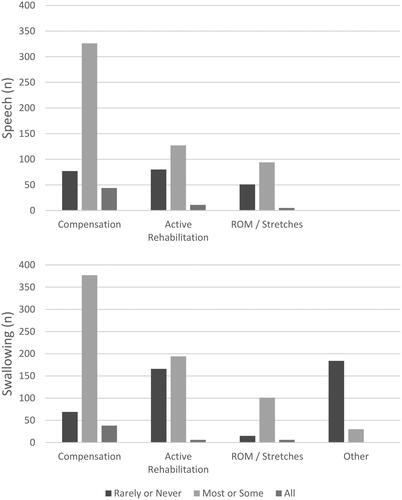

displays the cumulative SLP responses for a range of speech and swallowing interventions across all six oral cancer sites and highlights that SLPs predominantly recommended compensatory strategies for either speech or swallowing most or some of the time. Freidman’s rank test showed a significant difference in frequency of interventions recommended across the four swallowing intervention categories, Χ2(3) = 84.57, p < 0.001, and across the three speech categories, Χ2(2) = 51.39, p < 0.001. Post hoc analysis using Wilcoxon signed rank with Bonferroni corrected significance (p < 0.008) confirmed that SLPs recommended compensatory strategies significantly more than active rehabilitation and stretch/range of motion tasks (p < 0.001). Kendall’s coefficient of concordance showed strong agreement amongst SLPs in their swallowing (W = 0.65) and speech (W = 0.59) intervention recommendations.

Figure 2. Type and frequency of speech and swallowing interventions recommended. ROM = Range of motion.

When comparing speech to swallowing interventions, a post hoc Wilcoxon ranked analysis and Kendall’s coefficient showed SLPs recommended compensatory strategies significantly more for swallowing than speech (Z = −2.30, p = 0.02, W = 0.15) and active rehabilitation significantly more for swallowing than speech (Z = −3.57, p < 0.001, W = 0.3). There were no significant differences in stretch/range of motion recommendations for swallowing compared to speech.

To investigate whether SLPs use a range or combination of interventions, the percentage of SLPs selecting two or more interventions were calculated. Almost half the SLPs (42%, n = 30) selected two or more swallowing interventions, however, fewer SLPs (18%, n = 13) reported concurrent interventions for speech.

Frequency and intensity of active rehabilitation

As shown in , most SLPs recommended speech (71%, n = 24) or swallowing (76%, n = 26) interventions 7 days per week with up to three blocks of practice per day for swallowing (66%, n = 19) and speech (86%, n = 25). The number of repetitions was variable with SLPs equally likely to recommend more than 10 (50%, n = 15) or less than 10 (50%, n = 15) swallow exercise repetitions. For speech, most SLPs (65%, n = 17) recommended 10 or more repetitions per block of practice. This indicates a wide range of intervention dosage (repetitions x times per day x days per week; Warren et al., Citation2007). SLPs reported exercise dosage was dependent on individual factors, including patient motivation, fatigue, pain, and the intervention being recommended.

Table III. Frequency and intensity of speech and swallowing active rehabilitation.

Outcome measures

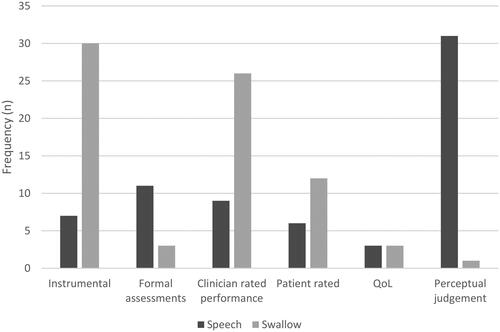

Most SLPs used instrumental assessments (40%, n = 30) and clinician ratings of performance (35%, n = 26) to measure change in swallow function. By contrast, SLPs predominantly selected perceptual judgements (46%, n = 31) to measure change in speech function (see ).

Review and discharge from speech-language pathology

More than half of SLPs did not routinely provide follow-up services for speech (79%, n = 27) or swallowing (62%, n = 21) in their clinical settings following cancer treatment. When follow-up reviews were scheduled, this service extended up to 3 months for swallowing and up to 6 months for speech. Almost all SLPs (76.5%, n = 26) discharged their patients from speech-language pathology services once both speech and swallowing therapy goals were achieved. However, SLPs commented this was in the presence of ongoing dysfunction with goal achievement being self-management.

Influences and barriers to practice

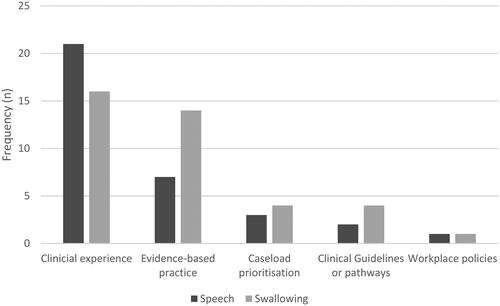

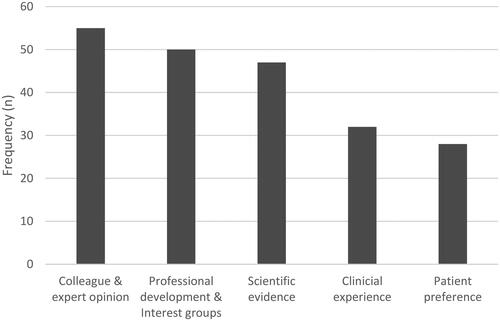

SLPs predominantly used their clinical experience to prioritise and determine when to initiate speech (62%, n = 21) and swallowing (41%, n = 16) services. When determining the most appropriate interventions, SLPs were most influenced by their SLP and interdisciplinary colleagues, as well as experts in HNC (n = 55, 25.9%). and demonstrate these influences.

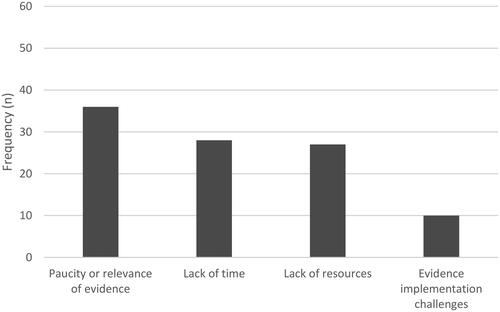

When rating barriers to practice, many SLPs (36%, n = 36) acknowledged the lack of quality or relevant evidence relevant to the oral cancer population. They also reported time (28%, n = 28) and resource (28%, n = 27) limitations within their workplace, for example, staffing limitations impacted on the timing of intervention and the ability to follow-up patients while a shortage of time limited their ability to find or read external evidence. Some SLPs (10%, n = 10) reported workplace challenges when attempting implementation of evidence (see ).

Discussion

This study benchmarks speech and swallowing interventions provided by Australian and New Zealand SLPs working with oral cancer survivors. We had several hypotheses and these are discussed below, along with the influences and perceived barriers to SLP services.

Service delivery

Our first hypothesis was that SLPs would provide intervention to patients with oral tongue, palate, and floor of mouth cancer more frequently than to patients with cheek or gum cancers. Across the oral cancer sites, SLPs reported seeing patients with oral tongue and floor of mouth cancers most frequently. This finding is consistent with the negative impact from cancer treatments to the oral tongue and floor of mouth to both speech and swallowing functions, hence patients with cancers at these sites may require greater SLP input when compared to other oral cancer sites (Kreeft et al., Citation2009).

Less than one-quarter of SLPs reported seeing patients with either hard or soft palate cancer despite the known impact to speech clarity and swallowing (Kreeft et al., Citation2009). It is unclear whether the low frequency of patients seen by SLPs following palate cancer was due to a lack of referral or due to low incidence of palatal cancers (Farah et al., Citation2014).

Our second hypothesis was that swallowing rehabilitation would be prioritised over speech. Swallowing intervention was predominantly commenced following a referral from head and neck teams or provided to all patients regardless of referral. In contrast, clinicians reported speech rehabilitation was mostly provided when patients self-reported speech dysfunction. This finding supports the hypothesis. Speech-language pathology services are directed towards risk minimisation, especially in the case of swallowing where aspiration pneumonia is a significant risk (Xu et al., Citation2015). An implication of this, however, is that patients who do not self-report a speech dysfunction may not receive intervention despite it being warranted.

The focus on risk minimisation within the acute setting is again highlighted by the frequent use of both instrumental assessments and clinician rated performance outcomes for swallowing. For speech dysfunction, by contrast, SLPs favoured the use of often informal perceptual judgments of intelligibility as an outcome measure. As perceptual judgments of intelligibility may not be a sensitive measure of improvement in articulation accuracy in HNC (Blyth et al., Citation2016), patients with a speech dysfunction who do not receive a more comprehensive assessment may be screened out of service eligibility and clinicians may lack precision in measuring therapy outcomes. For patients who are adapting the movements of their oral structures to produce clear articulation, a more accurate representation of improvement in speech would be articulatory precision (Blyth et al., Citation2016); however, the current study shows this type of measure is not frequently used by SLPs working in HNC.

It is important to note the disparity between the use of instrumental swallowing assessments and speech intelligibility ratings, as these measures focus on different levels of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF; World Health Organization, Citation2013). In ICF terms, instrumental assessments of swallowing focus on identifying dysfunction at the level of body functions and structures, whilst assessments of speech intelligibility focus on the level of participation. We cannot infer that an individual with a deficit in one component of the ICF will have the same deficit in another. It is, therefore, necessary to look at how oral cancer impacts not only body functions and structures but also participation, by utilising both instrumental assessments and perceptual judgements for speech and swallowing.

Interventions

Our third hypothesis was that SLPs would be more likely to recommend compensatory strategies compared to active rehabilitation. Across all oral cancer sites, SLPs were significantly more likely to recommend compensatory strategies rather than active rehabilitation for either speech or swallowing. This is consistent with the literature showing that compensatory strategies are predominantly used as intervention for the general population with swallowing dysfunction, and specifically for people with head and neck cancer (Lawson et al., Citation2017; Rumbach et al., Citation2018). Our finding indicates that patients may simply be managing their swallowing and speech dysfunction through altered posture or speech timing respectively. The reliance on compensatory strategies again indicates that speech-language pathology services are directed towards short-term management and risk minimisation (Rumbach et al., Citation2018) rather than rehabilitation to regain function.

Our fourth hypothesis, that SLPs would use a range of interventions, was confirmed. It appears that with this population, as with others (e.g.Chan et al., Citation2013), SLPs use two or more interventions concurrently with patients, which supports our hypothesis and is consistent with previous research showing that SLPs use a range of interventions even within a single therapy session (Lawson et al., Citation2017; Rumbach et al., Citation2018).

Frequency and intensity

Considering the varied range of intervention dosage recommended by SLPs in our survey, it is possible that clinicians were uncertain about the optimal frequency and intensity for therapy. This may be attributed to lack of evidence within speech-language pathology regarding optimal intensity across many therapies (e.g. Baker, Citation2012). Dysphagia intensity research is especially complicated due to a number of factors including the cause of dysphagia, reason for referral, patient age, patient environment, timing of intervention, and the use of a range of interventions concurrently (Baker, Citation2012; Greco et al., Citation2018). To identify optimal intervention intensity, it is necessary to understand (a) neural plasticity and behavioural and motor learning principles that facilitate learning, (b) patient factors, and (c) which components of intervention lead to their success (Baker, Citation2012). The optimal intensity for speech and swallowing interventions have not yet been established with the HNC population.

The duration of intervention varied amongst SLPs with most abandoning routine SLP follow-up beyond the acute period. This is consistent with previous research, which reported a shortage of SLP follow-up HNC clinics beyond 3 months post-radiotherapy (Lawson et al., Citation2017). The absence of long-term follow-up for patients following oral cancer treatment is of interest, as we know these patients experience chronic speech and/or swallowing dysfunction following surgery and, in particular, after additional chemoradiation (Baudelet et al., Citation2019; Kreeft et al., Citation2009). The mismatch in long-term speech-language pathology services reported in our study and the known chronic dysfunction suggests patients with speech and swallowing dysfunction may not be identified or prioritised for speech-language pathology services and will therefore continue to live with these potentially remediable dysfunctions.

Influences on practice

Most SLPs reported using a range of sources from the E3BP model (Dollaghan, Citation2007) to guide interventions, including journal articles, personal clinical experience, and patient preferences. Our study showed that SLPs’ decision making was also influenced by the opinions of colleagues and experts. This is consistent with Logan and Landera (Citation2021) who report SLPs frequently rely on their HNC colleagues and experts for clinical preparedness. Colleagues’ and experts’ opinions are not always the best source to guide clinical practice, due to specific biases, and peer encouragement to use particular approaches may make clinicians feel “out of step” if they do not conform (Lof, Citation2011).

Perceived barriers

Most SLPs reported limitations in quality evidence, time, and resources negatively impact on service delivery. The reported lack of high-quality evidence as a barrier for SLPs is not surprising considering there are very few papers exploring rehabilitation for people with oral cancer (Blyth et al., Citation2015). The lack of evidence to guide clinicians’ decision making is evident throughout the survey. For example, preference for personal clinical experience, rather than journal articles, as clinicians’ main reason for providing intervention; the frequent use of compensatory strategies rather than active rehabilitation; and using a range of interventions suggest it is unclear which interventions contribute to positive changes in speech and swallowing function.

Limitations

In survey studies, there is the potential for bias, including self-selection bias and response bias (Wright, Citation2006). In any given population, there are some individuals who are more likely to respond to surveys than others, causing a self-selection bias. Response bias may result from SLPs providing responses that they believe are socially desirable. These biases may limit the generalisability of our results to the entire HNC SLP population. We acknowledge participant numbers in this survey are small, however, they are representative of the specialist HNC SLP workforce within Australia and the specific oral cancer population targeted in this survey (Australian Institute of Health & Welfare, Citation2014; Lawson et al., Citation2017). The authors acknowledge the small number of SLPs from New Zealand, which is likely a result of less targeted recruitment amongst New Zealand HNC services. Due to the specific nature of this study, the results may not be generalised to populations that SLPs see more frequently.

Conclusion

The aim of this study was to benchmark clinical practices amongst Australian and New Zealand SLPs providing interventions to people with oral cancer. SLPs see people with tongue and floor of mouth cancer most frequently, swallowing intervention is prioritised through referral pathways, and compensatory strategies for either speech or swallowing are recommended significantly more than active rehabilitation. SLPs feel they are most influenced by their colleagues and expert opinions, and their ability to provide services are negatively impacted by time and resource limitations as well as limited high-quality rehabilitation evidence. There is a real need for the development of evidence-based clinical guidelines and high-quality, evidence-based active rehabilitative treatments for this patient population.

Supplementary Information - Survey Questions [abbreviated].pdf

Download PDF (481.9 KB)Acknowledgments

Thank you to the SLPs who spent time participating in this survey. Thank you also to Dr. Robert Heard for statistical support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author (KMB).

References

- Arrese, L. C., & Hutcheson, K. A. (2018). Framework for speech-language pathology services in patients with oral cavity and oropharyngeal cancers. Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Clinics of North America, 30(4), 397–410. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coms.2018.07.001

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2014). Head and neck cancers in Australia (Cancer series 83. Cat. no. CAN 80., Issue. AIHW. http://www.aihw.gov.au/publication-detail/?id=60129547291

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2021a). Chapter 5 Number of new cancer cases (CAN 144; AIHW. https://doi.org/10.25816/ye05-nm50

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2021b). Chapter 7 Survival and survivorship after a cancer diagnosis. AIHW. https://doi.org/10.25816/ye05-nm50

- Baker, E. (2012, Oct). Optimal intervention intensity in speech-language pathology: Discoveries, challenges, and unchartered territories. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 14(5), 478–485. https://doi.org/10.3109/17549507.2012.717967

- Balaguer, M., Pommee, T., Farinas, J., Pinquier, J., Woisard, V., & Speyer, R. (2020). Effects of oral and oropharyngeal cancer on speech intelligibility using acoustic analysis: Systematic review. Head & Neck, 42(1), 111–130. https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.25949

- Baudelet, M., Van den Steen, L., Tomassen, P., Bonte, K., Deron, P., Huvenne, W., Rottey, S., De Neve, W., Sundahl, N., Van Nuffelen, G., & Duprez, F. (2019). Very late xerostomia, dysphagia, and neck fibrosis after head and neck radiotherapy. Head & Neck, 41(10), 3594–3603. https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.25880

- Blyth, K. M., McCabe, P., Heard, R., Clark, J., Madill, C., & Ballard, K. J. (2014). Cancers of the tongue and floor of mouth: Five year file audit within the acute phase. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 23(4), 668–678. http://ajslp.pubs.asha.org/data/Journals/AJSLP/931141/AJSLP_23_4_668.pdf, https://doi.org/10.1044/2014_AJSLP-14-0003

- Blyth, K. M., McCabe, P., Madill, C., & Ballard, K. J. (2015). Speech and swallow rehabilitation following partial glossectomy: A systematic review. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 17(4), 401–410. https://doi.org/10.3109/17549507.2014.979880

- Blyth, K. M., McCabe, P., Madill, C., & Ballard, K. J. (2016). Ultrasound visual feedback in articulation therapy following partial glossectomy. Journal of Communication Disorders, 61, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcomdis.2016.02.004

- Chan, A. K., McCabe, P., & Madill, C. J. (2013). The implementation of evidence-based practice in the management of adults with functional voice disorders: A national survey of speech-language pathologists. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 15(3), 334–344. https://doi.org/10.3109/17549507.2013.783110

- Clarke, P., Radford, K., Coffey, M., & Stewart, M. (2016). Speech and swallow rehabilitation in head and neck cancer: United Kingdom national multidisciplinary guidelines. The Journal of Laryngology and Otology, 130(S2), S176–S180. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022215116000608

- Colangelo, L. A., Logemann, J. A., & Rademaker, A. W. (2000, May). Tumor size and pretreatment speech and swallowing in patients with resectable tumors. Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery: Official Journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, 122(5), 653–661. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0194-5998(00)70191-4

- Denaro, N., Merlano, M. C., & Russi, E. G. (2013, Sep). Dysphagia in head and neck cancer patients: Pretreatment evaluation, predictive factors, and assessment during radio-chemotherapy, recommendations. Clinical and Experimental Otorhinolaryngology, 6(3), 117–126. https://doi.org/10.3342/ceo.2013.6.3.117

- Dollaghan, C. A. (2007). The handbook for evidence-based practice in communication disorders. Paul H. Brookes Pub.

- Enderby, P. (2017). Speech pathology as the MasterChef: Getting the right ingredients and stirring the pot. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 19(3), 232–236. https://doi.org/10.1080/17549507.2017.1287219

- Farah, C. S., Simanovic, B., & Dost, F. (2014). Oral cancer in Australia 1982–2008: A growing need for opportunistic screening and prevention. Australian Dental Journal, 59(3), 349–359. https://doi.org/10.1111/adj.12198

- Foster, A., O’Halloran, R., Rose, M., & Worrall, L. (2016). Communication is taking a back seat: speech pathologists’ perceptions of aphasia management in acute hospital settings. Aphasiology, 30(5), 585–608. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2014.985185

- Gomez, M., McCabe, P., & Purcell, A. (2022). A survey of the clinical management of childhood apraxia of speech in the United States and Canada. Journal of Communication Disorders, 96, 106193–106193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcomdis.2022.106193

- Greco, E., Simic, T., Ringash, J., Tomlinson, G., Inamoto, Y., & Martino, R. (2018). Dysphagia treatment for patients with head and neck cancer undergoing radiation therapy: A meta-analysis review. International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics, 101(2), 421–444. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2018.01.097

- Jacobi, I., van Rossum, M. A., van der Molen, L., Hilgers, F. J. M., & van den Brekel, M. W. M. (2013). Acoustic analysis of changes in articulation proficiency in patients with advanced head and neck cancer treated with chemoradiotherapy. The Annals of Otology, Rhinology, and Laryngology, 122(12), 754–762. https://doi.org/10.1177/000348941312201205

- Joffe, V., & Pring, T. (2008). Children with phonological problems: a survey of clinical practice. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 43(2), 154–164. https://doi.org/10.1080/13682820701660259

- Kalavrezos, N., Cotrufo, S., Govender, R., Rogers, P., Pirgousis, P., Balasundram, S., Lalabekyan, B., & Liew, C. (2014, Jan). Factors affecting swallow outcome following treatment for advanced oral and oropharyngeal malignancies. Head & Neck, 36(1), 47–54. https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.23262

- Kolokythas, A. (2010). Long-term surgical complications in the oral cancer patient: A comprehensive review. Part II. Journal of Oral & Maxillofacial Research, 1(3), e2. https://doi.org/10.5037/jomr.2010.1302

- Kreeft, A. M., van der Molen, L., Hilgers, F. J., & Balm, A. J. (2009, Nov). Speech and swallowing after surgical treatment of advanced oral and oropharyngeal carcinoma: a systematic review of the literature [Review. European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology: Official Journal of the European Federation of Oto-Rhino-Laryngological Societies (EUFOS): Affiliated with the German Society for Oto-Rhino-Laryngology - Head and Neck Surgery, 266(11), 1687–1698. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-009-1089-2

- Krisciunas, G. P., Sokoloff, W., Stepas, K., & Langmore, S. E. (2012). Survey of usual practice: Dysphagia therapy in head and neck cancer patients. Dysphagia, 27(4), 538–549. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-012-9404-2

- Lango, M. N., Egleston, B., Fang, C., Burtness, B., Galloway, T., Liu, J., Mehra, R., Ebersole, B., Moran, K., & Ridge, J. A. (2014). Baseline health perceptions, dysphagia, and survival in patients with head and neck cancer. Cancer, 120(6), 840–847. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.28482

- Lawson, N., Krisciunas, G. P., Langmore, S. E., Castellano, K., Sokoloff, W., & Hayatbakhsh, R. (2017, Apr). Comparing dysphagia therapy in head and neck cancer patients in Australia with international healthcare systems. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 19(2), 128–138. https://doi.org/10.3109/17549507.2016.1159334

- Levin, J., & Fox, J. A. (2006). Correlation (10th ed.). Pearson Allyn and Bacon.

- Lof, G. L. (2011). Science-based practice and the speech-language pathologist. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 13(3), 189–196. https://doi.org/10.3109/17549507.2011.528801

- Logan, A. M., & Landera, M. A. (2021). Clinical practices in head and neck cancer: a speech-language pathologist practice pattern survey. The Annals of Otology, Rhinology, and Laryngology, 130(11), 1254–1262. https://doi.org/10.1177/00034894211001065

- Ministry of Health. (2021). New Cancer Registrations 2019. https://www.health.govt.nz/publication/new-cancer-registrations-2019

- National Institute for Clinical Excellence. (2004). Improving outcomes in head and neck cancers - the manual. NHS. www.nice.org.uk

- Nund, R. L., Rumbach, A. F., Debattista, B. C., Goodrow, M. N., Johnson, K. A., Tupling, L. N., Scarinci, N. A., Cartmill, B., Ward, E. C., & Porceddu, S. V. (2015). Communication changes following non-glottic head and neck cancer management: The perspectives of survivors and carers. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 17(3), 263–272. https://doi.org/10.3109/17549507.2015.1010581

- Nund, R. L., Ward, E. C., Scarinci, N. A., Cartmill, B., Kuipers, P., & Porceddu, S. V. (2014, May). Survivors’ experiences of dysphagia-related services following head and neck cancer: Implications for clinical practice. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 49(3), 354–363. https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12071

- Paleri, V., & Roland, N. (2016). Head and neck cancer: United Kingdom national multidisciplinary guidelines [Special Issue]. The Journal of Laryngology & Otology, 130(S2), S1–S224. https://static.cambridge.org/content/id/urn:cambridge.org:id:article:S0022215116000608/resource/name/JLO130_S2.pdf

- Pauloski, B. R., Rademaker, A. W., Logemann, J. A., Stein, D., Beery, Q., Newman, L., Hanchett, C., Tusant, S., & MacCracken, E. (2000). Pretreatment swallowing function in patients with head and neck cancer. Head & Neck, 22(5), 474–482. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0347(200008)22:5

- Riemann, M., Knipfer, C., Rohde, M., Adler, W., Schuster, M., Noeth, E., Oetter, N., Shams, N., Neukam, F. W., & Stelzle, F. (2016, Jul). Oral squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue: Prospective and objective speech evaluation of patients undergoing surgical therapy. Head & Neck, 38(7), 993–1001. https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.23994

- Rodriguez, A. M., Komar, A., Ringash, J., Chan, C., Davis, A. M., Jones, J., Martino, R., & McEwen, S. (2019). A scoping review of rehabilitation interventions for survivors of head and neck cancer. Disability and Rehabilitation, 41(17), 2093–2107. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2018.1459880

- Roe, J. W., Carding, P. N., Rhys-Evans, P. H., Newbold, K. L., Harrington, K. J., & Nutting, C. M. (2012). Assessment and management of dysphagia in patients with head and neck cancer who receive radiotherapy in the United Kingdom - A web-based survey. Oral Oncology, 48(4), 343–348. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oraloncology.2011.11.003

- Rumbach, A., Coombes, C., & Doeltgen, S. (2018, Apr). A survey of Australian Dysphagia practice Patterns. Dysphagia. Dysphagia, 33(2), 216–226. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-017-9849-4

- Stelzle, F., Knipfer, C., Schuster, M., Bocklet, T., Nöth, E., Adler, W., Schempf, L., Vieler, P., Riemann, M., Neukam, F. W., & Nkenke, E. (2013). Factors influencing relative speech intelligibility in patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma: a prospective study using automatic, computer-based speech analysis. International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, 42(11), 1377–1384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijom.2013.05.021

- Suarez-Cunqueiro, M. M., Schramm, A., Schoen, R., Seoane-Leston, J., Otero-Cepeda, X. L., Bormann, K. H., Kokemueller, H., Metzger, M., Diz-Dios, P., & Gellrich, N. C. (2008). Speech and swallowing impairment after treatment for oral and oropharyngeal cancer. Archives of Otolaryngology-Head & Neck Surgery, 134(12), 1299–1304. https://doi.org/10.1001/archotol.134.12.1299

- Warren, S. F., Fey, M. E., & Yoder, P. J. (2007). Differential treatment intensity research: a missing link to creating optimally effective communication interventions. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews, 13(1), 70–77. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrdd.20139

- World Health Organization. (2013). How to use the ICF: A practical manual for using the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). Exposure draft for comment. https://www.who.int/classifications/drafticfpracticalmanual.pdf

- Wright, K. B. (2006). Researching internet-based populations: Advantages and disadvantages of online survey research, online questionnaire authoring Software Packages, and Web Survey Services. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 10(3), 00–undefined. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2005.tb00259.x

- Xu, B. B., Boero, I. J., Hwang, L., Le, Q. T., Moiseenko, V., Sanghvi, P. R., Cohen, E. E. W., Mell, L. K., & Murphy, J. D. (2015). Aspiration pneumonia after concurrent chemoradiotherapy for head and neck cancer. Cancer, 121(8), 1303–1311. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.29207