Abstract

Purpose

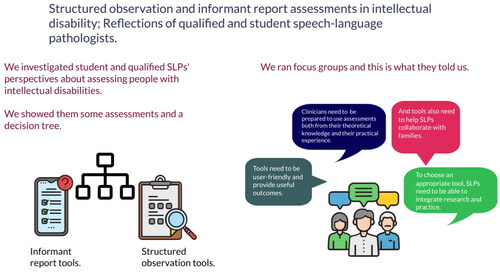

The purpose of this study was to explore the perspectives of qualified and student speech-language pathologists (SLPs) on the clinical utility of informant report and observation tools following a 1-day workshop using a decision tree.

Method

Each participant group (qualified [n = 4] or student SLP [n = 8]) attended a 1-day workshop where they engaged with informant report and structured observation tools using video case studies. Each workshop concluded in a focus group conducted by an independent researcher. NVivo 12 software supported inductive coding and subsequent thematic analysis of transcribed data.

Result

Thematic analysis revealed that participants’ perceptions of tools’ clinical utility could be conceptualised as three themes (a) tool characteristics, (b) external clinical work demands, and (c) clinician preparedness.

Conclusion

Participants’ views on the utility of informant report and structured observation were influenced by tensions between their desires, the realities of clinical practice, and their own capabilities. This has implications for workforce development in the field in providing clinician guidance, training, and support.

Introduction

People with severe intellectual disability often display idiosyncratic and informal behaviours that could have communicative potential, but only when interpreted as such (Sigafoos et al., Citation2000). These are referred to as potential communicative acts (PCAs). Assessment needs to consider the individual’s communication as well as that of the communication partner and also environmental factors (Siegel-Causey & Bashinski, Citation1997).

Non-standardised assessment is most appropriate for people with severe intellectual disability using either informant report, where communication partners are asked specific questions, or direct observation, which can be structured or unstructured (Ogletree & Price, Citation2018). Ethical assessment should involve the use of multiple tools (Brady et al., Citation2016), used to triangulate information from both informant reports with observation (Lyons et al., Citation2017). Informant reports allow efficient collection of ecologically valid information (Brady & Keen, Citation2016), as behaviour of individuals with severe intellectual disability varies widely in different contexts. Observation provides ecologically valid information about communication opportunities rendered by communication partners (Keen et al., Citation2005), but is limited by observable contexts (Brady & Keen, Citation2016). Therefore, behaviours of interest might not be fully detected (Johnson et al., Citation2011). Further, observation can be time-consuming in administration and analysis (Brady et al., Citation2010).

Several informant report tools are available and suitable for use with people with severe intellectual disability, including the Inventory of Potential Communicative Acts (IPCA; Sigafoos et al., Citation2000), the Pre-Verbal Communication Schedule (PVCS; Kiernan & Reid, Citation1987), the Pragmatics Profile (Tan et al., Citation2023), the Communication Matrix (Rowland, Citation2011), and the Triple C: Checklist of Communicative Competencies (Bloomberg et al., Citation2009). The tools differ in focus but achieve the same purpose, which is to find out information about how the person communicates in their daily life by asking questions of a range of communication partners. Research into the reliability of informant report reveals mixed findings. Some studies compared parent and caregiver-identified potential communicative act judgments to those made by researchers and found high rates of similarity between the two (Braddock et al., Citation2017; Crais et al., Citation2004). Conversely, other studies found differing levels of agreement between informants (Cascella et al., Citation2012), for instance, where familiar communication partners are more confident and accurate than unfamiliar communication partners in their judgements of intentional communication (Meadan et al., Citation2012). Therefore, while using informant report allows for holistic understanding of the individual’s capabilities, the reliability of this information depends on informant factors, including their skill and familiarity with the individual.

Direct, unstructured observation involves observing individuals’ naturalistic communication. The term structured observation can refer to structuring interactions by setting up situations with communicative opportunities (Ogletree & Price, Citation2018), but the term structured can also be used for devices that structure observations through checklists or codes. This study focuses on this latter definition, whereby structured observation has been used to categorise observed behaviours, and to document the influence of environmental triggers on the individual’s behaviours (Carroll et al., Citation2006). This documentation process has been found to increase observer confidence in their observations, and facilitate consideration of possible behaviour triggers, arguably allowing detailed and thorough behaviour analysis necessary with this population given characteristic communicative complexities (Porter et al., Citation2001).

To our knowledge, only one structured observation tool exists for use with people with severe intellectual disability. A Model of Observational Screening for the Analysis of Interaction and Communication (MOSAIC; Smidt, Citation2020) provides a framework for gathering and documenting observations of an individual’s communication, in the context of interactions with communication partner(s) in different environments (Smidt, Citation2020). It aims to scaffold in-depth interpretation of observations within a system of dynamic assessment (Smidt, Citation2020). While MOSAIC appears to fill a need in scaffolding the observation of behaviours that are challenging to interpret, its clinical utility has not yet been investigated.

Clinically useful assessment tools should provide in-depth, accurate, and relevant information to plan functional and relevant goals (Ogletree et al., Citation1996), and be evaluated based on this criteria. However, tools are often evaluated based on objective validity and reliability measures. For instance, the Triple-C: Checklist of Communicative Competencies (Bloomberg et al., Citation2009; an informant report tool) has robust internal consistency and reliability (Iacono et al., Citation2009). However, the authors acknowledge it is unknown whether Triple C completion facilitates support workers’ understanding of individuals’ communicative potential, which would be necessary in goal planning. Literature on the extent to which assessment tools generate valuable outcomes is limited.

A recent survey of UK speech-language pathologists (SLPs) found that clinicians judged a tool’s clinical utility based on whether it provided information about the individual, informed intervention planning, facilitated collaboration, and on its pragmatic feasibility (Chadwick et al., Citation2019). The authors, however, acknowledged that the survey methodology used was limited in investigating clinicians’ rationales and emphasised the need for qualitative studies using interviews or focus groups to explore clinician rationales in decision-making (Chadwick et al., Citation2019). Clinically useful tools must meet subjective measures of relevance, practicality, and functionality (Smart, Citation2006) and so clinician views on assessment tools is vital but currently lacking (Cunningham et al., Citation2019).

In Australia, the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) has heralded a growth in demand for skilled SLPs in disability (Hines & Lincoln, Citation2016), who must be prepared to meet individuals’ complex support needs and collaborate regarding funding allocation (Dew et al., Citation2019). Understanding clinicians’ needs in the field, including assessment, is therefore necessary (Hines & Lincoln, Citation2016).

This qualitative study explores the perspectives of qualified SLPs (Q-SLPs) and student SLPs (S-SLPs) on the clinical utility of informant report and structured observation tools in assessing communication needs of individuals with severe intellectual disability, and the factors impacting these perspectives, which has wider implications for training in the field. Qualitative research allows insight into the complexities of clinicians’ decision-making, by directly engaging with them and giving them a voice (Cunningham et al., Citation2019).

Research aims and questions

This study investigates the clinical utility of two specific informant report tools, the IPCA (Sigafoos et al., Citation2000) and the PVCS (Kiernan & Reid, Citation1987), and one structured observation tool, MOSAIC (Smidt, Citation2020), following a 1-day workshop introducing participants to these tools.

This qualitative study seeks to answer the following:

What are the perceptions of qualified and student SLPs on using informant report and structured observation assessments to assess the communication of individuals with severe intellectual disability?

What factors impact these perceptions?

How might this impact speech-language pathology student training?

Method

Participants

Purposive sampling was utilised to recruit participants who were Q-SLPs or S-SLPs. Q-SLPs needed to have at least 2 years clinical experience with people with a disability. S-SLPs needed to have completed the unit of study in which they were taught about working with people with a disability. Participants were recruited via social media posts containing the participant information statement, an expression of interest form, and consent form. Participants consisted of four Q-SLPs and eight S-SLPs. Q-SLPs had experience in disability, while students had completed the Lifelong Disability and Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) unit of study at an Australian university. Participants completed a demographic questionnaire. and outline summaries of participant data.

Table I. Qualified speech-language pathologist (Q-SLP) participant demographics.

Table II. Student speech-language pathologist (S-SLP) participant demographics.

This study was approved by the University of Sydney (ethics approval ID: 2018/900). All participants gave verbal and written consent prior to study participation. An independent researcher conducted the focus groups, allowing participants to share their views without perceived judgement or risk to their relationship(s) with the investigator(s), given that two of the authors had an affiliation with one or more of the tools. Further, although the second author lectures the Lifelong Disability and AAC unit, S-SLPs had already completed this unit. Their focus group responses would, therefore, not have impacted their academic results.

Research design

This study was a qualitative pilot investigation, exploring the usefulness of informant report and structured observation tools used by SLPs working with people with severe intellectual disability. Q-SLPs and S-SLPs participated in separate 1-day workshops focused on goal planning using informant report and structured observation tools. The qualitative methodology allowed for exploration of SLPs’ perspectives on tools used during the workshop through focus groups conducted on completion of each workshop.

Focus groups allowed insight into participants’ practices and decisions, with the group dynamic supporting open sharing. The capacity of focus groups to consolidate responses to recent events allowed the capture of SLPs’ perspectives immediately post-workshop. A thematic networks analysis approach was used to analyse the data (Attride-Stirling, Citation2001). A realist or essentialist method to thematic analysis was adopted, focused on reporting the experienced reality of the participants (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006) based on data interpretation (Clarke & Braun, Citation2017).

Materials and procedure

Two 1-day workshops were provided, one for Q-SLPs and one for S-SLPs. The workshop used a decision tree () to explain the process of assessment and demonstrated use of informant report and structured observation tools using videos of one child and one adult with a disability. Participants first examined completed informant report tools about each client and then attempted to write goals for that person. They were then shown videos of the person and they completed a MOSAIC form using the video and again attempted to write goals for that person.

Data collection

Focus group discussions were conducted by an independent researcher who is a qualified occupational therapist and lecturer, experienced in intellectual disability and running focus groups. Flexible, semi-structured topic guides were developed following formation of research questions, to include questions about participants’ perspectives on (a) using tools in workshops and clinical practice, (b) goals they had set, and (c) training needs. Discussions were conducted with reference to guides but followed participants’ flow of interest. The first author recorded field notes and contributed input towards the end.

Data analysis

Focus group discussions lasted for approximately 1 hour and 15 minutes, were audio-recorded, and transcribed by the first author, allowing data familiarisation (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). Focus group data were analysed using thematic networks analysis, which structures and depicts different theme levels from a dataset using a web-like network (Attride-Stirling, Citation2001). Data were first coded inductively, without pre-existing coding frames. This process was supported by QSR International’s NVivo12 software, which stored all transcripts and codes. The codes were then grouped into key themes by the first and second author, an exemplar of which is in . Themes were refined together with the independent researcher who conducted the focus groups, to ensure themes were sufficiently representative of the dataset. Thematic networks were organised in a hierarchy of basic-organising-global themes in order of breadth (Attride-Stirling, Citation2001). Illustrative quotes were used to describe each network and each network was summarised. Finally, themes were linked back to the overall research questions and literature (Attride-Stirling, Citation2001).

Table III. Data analysis exemplar for subtheme: Practical experience.

Researchers

An awareness of researcher identity and perspectives allows research transparency and credibility. The first author is an undergraduate speech pathology Honours student at an Australian university. The primary supervising researcher is a speech pathologist who authored MOSAIC, while other researchers included a special education researcher with a role in publishing the IPCA and another speech pathologist experienced with the NDIS. The second and fourth authors are lecturers at major universities in Australia. These backgrounds could have influenced their interpretations of participants’ views of tools. Inductive analysis, transparent documentation, and researcher reflexivity were critical in mitigating the influence of researcher bias.

Research credibility

Member checking processes were employed to ensure authenticity of participant perspectives (Birt et al., Citation2016), whereby participants were invited via email to verify their transcript sections. No participants expressed dissent. The first and second author met regularly to discuss data interpretations, ensuring trustworthiness of findings. Another student also coded a subset of focus group data, with cross-checking of codes to ensure reliability of the coding process and outcomes (Carter & Little, Citation2007). An audit trail was established through the first author recording her observations during data analysis in a document, which enhanced research credibility by considering the researcher’s influence on the research process.

Result

As shown in , the central emergent theme was about how tool characteristics impacted tool choice, which was subdivided into (a) the outcomes of using each tool and (b) user-friendliness. However, participants also identified two additional themes—external clinical work demands and clinician preparedness—that impacted their decision-making.

Theme 1: Tool characteristics

The central theme relates to tool characteristics that impacted tool choice, including (a) their outcomes, and (b) their user-friendliness.

Outcomes

Q-SLPs reported that they valued tools that provided comprehensive and accurate insight into the person, their communication partners, and the environment. Participants acknowledged that both informant report and structured observation allowed insight into the person, but highlighted how “seeing” the client resulted in them being “a lot more confident after watching the video” (Q-SLP1), which extended beyond just the person: “my confidence increased a bit when I did MOSAIC, because … I got to see the communication partner” (S-SLP6).

However, participants commented that structured observation was limited in allowing insight into communicative functions and contexts, whereby “[in structured observation] so you get a snippet of someone playing and you don’t really see anything” (Q-SLP2) depending on which video segment they were watching and “you might not see the refusal that they described” (Q-SLP4). Conversely, informant report was perceived to provide contextual information, whereby “IPCA [informant report] starts with greetings and then talks about refusal … so you go through all these different contexts and you say, ‘mm what do they do around this’” (Q-SLP2).

Despite this, participants acknowledged structured observation’s potential in gleaning rich information, for example, one Q-SLP explained that MOSAIC provides insight into “one small area but it’s definitely a broader view of that small area” (Q-SLP2). In comparison to informant report, “information we get from that [MOSAIC] … it’s really quite different. I think it’s a lot richer” (S-SLP3). In particular, participants valued the structured nature and video components of structured observation in gathering comprehensive insights: “if I was … just taking notes, I might not have said, ‘oh I didn’t actually look for what types of cues they were doing or whether they were pointing or … using gesture’” (Q-SLP2).

Participants also particularly valued having insight into communication partners’ behaviours. They felt this was important as reactions of individuals with severe intellectual disability “are not so predictable” (S-SLP2) and intervention typically involves communication partners: “we’re changing the environment and the communication partner, not the person with the disability” (Q-SLP3). Participants also noted that insight into communication partners judgements was necessary because “when the informant is reporting something … it’s not always going to be a communicative act” (Q-SLP2). Specifically, structured observation was perceived to give “you more about the communication partner” (S-SLP6), whereas “the IPCA [informant report] … gives you a sense of what the person but not what their partner does” (Q-SLP2). Overall, whilst participants identified strengths and limitations of both types of tool, they ultimately viewed the need to use both informant report and structured observation “in conjunction with each other to help … get a better understanding of the client” (S-SLP6).

Participants described the above insights as informing goal planning, with structured observation allowing goal planning “looking beyond … the person … more at … their communication partners and … goals we can set to … target their perspective, and how they can work with the person” (S-SLP7). Informant report tools, however, provided less communication partners’ information on which to base goals. For example, one S-SLP explained, “when I only had the questionnaires, I felt that I could only set goals based on the client. Because that’s the only information I got” (S-SLP7). Participants also considered how structural aspects of tools facilitated goal planning. They commented that the MOSAIC goal form encouraged holistic goal planning by including specific prompts to consider, “how is this going to either increase their independence, assist with their social interactions, or their participation” (Q-SLP2) and “setting a time frame and how we’re gonna do that” (S-SLP7). A number of S-SLPs, however, found the form constraining because “it was like ‘the person will do this … with this support.’ And I think that encouraged me to write a goal about the client” (S-SLP6).

Participants reported informant report tools provided scaffolding, which facilitated goal planning by breaking “it down into the different communicative acts … so that was a bit easier for me to set my goals based on what they … could or could not do” (S-SLP3). One S-SLP also commented that the PVCS guided goal setting based on a skill development hierarchy: It “gave you … a preverbal, and then verbal one, then you could … go … what’s the next … step in terms of communicative acts” (S-SLP8). Conversely, some participants commented that structured observation lacked this structure, resulting in potential challenges with goal-setting: “for MOSAIC, I … have to … analyse it, and … break it down into the different acts myself … I was … a bit lost … when I had to make goals” (S-SLP3). For a number of participants, however, structured observation was seen to facilitate behaviour interpretation and goal planning: “I … found these columns quite useful to … look at, ‘okay, this person’s not using any kind of cues.’ …That’s obviously a goal straightaway” (Q-SLP2).

Q-SLPs valued tools which facilitated collaboration with families, that structured observation and “having that conversation with families around, ‘you’re gonna have to do something with therapy, it’s not about me fixing your child, we need to work together’” (Q-SLP3). Other Q-SLPs raised the potential utility of structured observation’s structure and video clips in showing parents … what you’ve written down …. for them to go, ‘oh!’ Like that lightbulb moment” (Q-SLP3) and in sharing feedback “that gives a teaching opportunity too, ‘cos you can acknowledge what happened when, so and so did this” (Q-SLP4), “and it makes them feel like a part of the assessment process more” (Q-SLP3).

User-friendliness

Participants perceived that different skill levels were required to use different types of tools in both administration and analysis. They related this to stage of career: “when you’re starting out, you really need that structure to make sure you’re focusing on the right things and you’re not missing things” (Q-SLP1). Participants commented on ease of informant-report administration in gathering information, due to their structure whereby “it’s [informant report] easy to administer, quick to score” (S-SLP7) and “can help structure responses a little bit more and give you an idea of what you can work with” (Q-SLP2). Whereas participants felt that MOSAIC required clinicians to have more advanced behaviour interpretation skills, whereby “you have to give your own opinion on what they’re trying to express” (S-SLP1). One student highlighted specific challenges with this: “so … if the client vocalised and flapped their hands, I would … try to categorise that … it wasn’t a speech behaviour … it wasn’t a behaviour behaviour. But it wasn’t a gesture either” (S-SLP7).

Clinicians also perceived that a baseline understanding of communicative functions was required to use MOSAIC. One Q-SLP explained, if “you don’t have … knowledge of … functions of communication … you’re … interpreting things against what you should know, but it’s not right there in front of you” (Q-SLP2). A number of S-SLPs, however, acknowledged MOSAIC’s value in facilitating behaviour interpretation. One S-SLP explained finding MOSAIC “nicely scaffolded … I was able to mark specific areas. … Was the … communicative attempt successful?” (S-SLP7), while another commented that MOSAIC facilitated behaviour interpretation more so than informant report tools: “MOSAIC helped me interpret … what was happening … when I read the … other forms, I didn’t know what I was reading” (S-SLP6). Informant report tools were seen to require less skill in behaviour interpretation, and therefore were potentially more useful for less experienced clinicians: “perhaps IPCA for a new staff member … might give them … a framework around, ‘… these are the things that could be happening,’ whereas MOSAIC doesn’t have that” (Q-SLP3).

Participants valued tools facilitating ease and efficiency of assessment. Participants noted MOSAIC required greater administration time, “you’re supposed to look at it and then come up with dynamic assessment, … and … continuously …modify what you’re doing based on what you’ve observed. But I think just the time taken for that” (Q-SLP2). Informant report was perceived to be more efficient both in administration and results analysis, “I get a lot more out of assessment when I go in with informant report already in my back pocket” (Q-SLP2)

Participants spoke about specific features of each tool they found user-friendly. For example, visual summaries in informant report that helped to “summarise it and really get to the nitty gritty of what I really … need to know” (S-SLP2), and the PVCS’ behaviour frequency scale: “it was … usually or rarely or never, that’s always … more comprehensive to … look at, than ‘what do they do?’” (Q-SLP2). Participants also valued how specific informant report tools allowed recording of specific examples to clarify, “does it happen all the time or sometimes, or with different people, or across environments … the other one [PVCS] doesn’t allow for that … you’d have to be taking notes” (Q-SLP3).

Theme 2: External clinical work demands

In the second theme, participants discussed how assessment and tool choice would be influenced by the need to (a) collaborate with families and (b) integrate research with clinical practice.

Collaborating with families

Participants felt that collaboration with families was needed to plan goals “functional, to the family” (S-SLP1) because “it’s not about me and what I want them to do” (Q-SLP3). Participants also noted that collaboration was important because meaningful outcomes were “always … about independence, social participation … doing things that people want … to have a meaningful life” (Q-SLP3). Participants viewed family involvement as especially important, where “a lot of what we do is … with the families” (Q-SLP4).

Participants described needing to negotiate assessment with families and that families often did not understand or value assessment. One Q-SLP felt that, “because families come in with the NDIS goal, they already know what they wanna work on, so they don’t really understand assessment” (Q-SLP2). Participants also described families as prioritising therapy over assessment: “mom called me to say, ‘I want you to stop the communication assessment and just do therapy’” (Q-SLP2). Participants felt this was linked to time and funding demands, “if clients are paying … quite a significant amount for their therapy, they want to see you jump in straightaway and push, push, push … see that change” (S-SLP2). Participants thus saw assessment as, “hard to quantify … in terms of … the money spent, the time, the effort” (S-SLP4) and raised concerns about potentially time-consuming tools. Participants described needing to consider, “what time do I have … what do I know how to use, and I can do quickly, versus I know that’s a really good tool but I don’t have time” (Q-SLP3).

Student participants described pressure to meet family expectations and sometimes giving in to this pressure: “I generally have felt quite pressured to set a goal that’s attainable enough for the family to see change” (S-SLP7). Meanwhile, Q-SLPs acknowledged this pressure but emphasised the need to negotiate with families, “making sure whatever’s being said is actually acknowledged regardless of what your thought is about it” (Q-SLP4), and adapt their practice, being “more creative … and more efficient in what we do in … 10 hours of therapy for a whole year” (Q-SLP3).

Integrating research with clinical practice

Another challenge that influenced choice of assessment tools was the need to integrate research and clinical practice. In this Australian context, Q-SLPs perceived that the NDIS primarily valued research evidence in substantiating their practices, “it’s hard because they [NDIS] may … say, ‘well you didn’t put in any evidence, where are the journal articles that say this works?’” (Q-SLP3), but identified a paucity of this: “and you’re … like … there is none’ (Q-SLP3). Q-SLPs described needing to balance research with clinical experience and client preferences, and highlighted tension in meeting funders’ priorities because, “evidence-based practice is more than just the research side of things, but they don’t wanna hear about your own clinical expertise or what families want” (Q-SLP3). SLPs also raised the necessary influence of colleagues’ clinical experience, where “the people around you are saying, ‘this is good for this purpose’, and so you just go with that because it’s … it’s useful” (Q-SLP4). One Q-SLP highlighted this as being part of workplace practice culture: “you get to … tools that your current workplace is already using” (Q-SLP4).

One S-SLP summarised the impact of these competing demands on clinician practice:

as much as we … have an ideal of choosing exactly the right tool for them … and spending all that time analysing, I think the reality of … clinical practice in different settings and how you’re being paid and how … clients are going to react to what you do, it changes the way that you work. Much more than you wish it would. (S-SLP2)

Theme 3: Clinician preparedness

The final theme relates to the perceived impact of clinician preparedness in terms of (a) theoretical knowledge and (b) experiential learning on participants’ ability to assess people with a disability.

Theoretical knowledge

Participants described their theoretical learning and its impact on speech-language pathology assessment practice, firstly in the university setting and then once qualified. Overall, Q-SLPs felt they graduated from university ill-equipped to work with the disability population: “I really felt like I came out not knowing a lot about the developmental disability population” (Q-SLP1). They acknowledged this was complex because, “everyone is so different with any kind of disorder” (Q-SLP2) and “[you would] need a whole Master’s degree on disability to actually fill across it all” (Q-SLP2).

More specifically, Q-SLPs felt that their university learning about assessment and goal setting was limited as, “it was very much learning how to do standardised assessments and that was it” (Q-SLP3) and “at uni there’s such an emphasis on SMART goals” (Q-SLP1), but not on writing functional goals. This was perceived to impact the support clinicians needed to provide to new graduates: “I’m having to reteach them how to write goals in a functional way … they don’t have that skill when they graduate” (Q-SLP3).

S-SLPs felt differently, identifying that functional assessment and goal-planning concepts had been emphasised in their learning. They explained, “we’ve always been taught to think of our clients very holistically” (S-SLP3) and “it was very much drilled in[to] us that our typical standardised assessments won’t work … we’re all … aware that we need to set functional goals” (S-SLP7). However, while S-SLPs reported knowing that standardised assessments were not appropriate, one S-SLP commented: “we also don’t really know what else there is” (S-SLP6).

Participants also discussed their learning once qualified, noting that ongoing learning was needed to build their confidence generally, “professional development opportunities … in … centres … specific for disability … will increase confidence of clinicians” (S-SLP6), and more specifically about assessment tools because, “as a clinician you typically stick with what you know” (S-SLP7). They also felt that knowledge of tools would allow them to make more informed and appropriate decisions, “understanding what sort of assessments to do. So … before this [the workshop] I would have just done … one of the questionnaires” (S-SLP6). They acknowledged needing more knowledge about “different types of assessment … depending on what goal you’re working on” (Q-SLP3). One Q-SLP identified the impact of lack of knowledge on confidence in assessment: “we didn’t know what tools were available … we were too scared to go in because we felt we didn’t have the knowledge” (Q-SLP1).

Although it was perceived that “most therapists want to learn new assessments and learn new ways of doing things” (Q-SLP3), clinicians’ learning within current workplace models (the NDIS) was perceived to be limited, as “time in the new world doesn’t permit for learning and development” (Q-SLP3).

Practical experience

Participants commented on the importance of practical experience, alongside theoretical knowledge, in being prepared to work with people with a disability. For example, one participant explained, “if you’ve got no experience working with disability or disability cohorts … it’s still a blank slate where you’re like, ‘wow I’ve got no idea what’s going on here’” (Q-SLP3). Lack of experience, particularly of new graduates and student SLPs, impacted their confidence and assessment decisions. One S-SLP identified that being “early speech pathologists … still trying to develop our persona and our understanding … about the profession” (S-SLP4) impacted their competence and confidence, which impacted their assessment decisions:

if I were a new grad … and no one was watching over my shoulder, I may take more time on certain things … I may choose to investigate further. But … given I have a supervisor … who is more knowledgeable than me, I may be quicker to jump to what I think they want me to do. (S-SLP2)

Q-SLPs noted that lacking experience impacted clinicians’ flexibility in assessment, particularly in conducting dynamic and informal, less structured assessment: “once you’ve been in a certain area for a really long time it might be easier for you to do it … in a less structured way, but … when you’re starting out you really need that structure” (Q-SLP1). Experience also impacted functional goal setting, which includes skills in synthesising and translating client information. One S-SLP described this as “how do I take my knowledge of what I know, and … transfer that into planning goals” (S-SLP4), particularly working in a disability setting: “in other forms of speech pathology, it’s … really concrete goals … But for this one, it’s such a specific behaviour you need to work with” (S-SLP4). Disability-specific experience in goal setting was therefore seen as particularly important because, “if you don’t do a disability placement you don’t practice writing disability goals, you might learn about it in the disability subject, but … it’s not something that gets ingrained” (Q-SLP2). Experience also impacted realistic goal setting, where Q-SLPs perceived that: “new grads … come in with a preconceived idea of what the outcome will be … but back here we’re like, ‘if we can do one tenth of that part of the goal in a year, that would be more realistic’” (Q-SLP3).

Finally, participants valued opportunities for practical experience, in learning to conduct assessment and use assessment tools, together with more experienced clinicians. This impacted participants’ perceptions of tool usefulness in terms of available support: “I would really love to have the support of someone who knows the tool to make sure I am doing it right” (Q-SLP1); “I feel like I’d want to do this with a couple of speechies … we’re all rating … the same thing, we’re looking at the same behaviours and just talking about our interpretation” (Q-SLP1).

Discussion

This study explored perspectives of qualified and student SLPs about informant report and structured observation tools, and the factors influencing their perspectives. As illustrated in , participants’ views were influenced by tensions in balancing competing priorities of (a) valuing comprehensiveness and collaboration, (b) managing workplace demands, and (c) considering their personal capabilities. This study also considered implications for student training.

Valuing comprehensiveness and collaboration

Emerging themes indicated that participants valued tools providing comprehensive information and viewed informant report as providing particularly rich environmental information; whereas structured observation provided insights beyond those of informant report, into the communication partner (Chadwick et al., Citation2019). This was valued in the context of collaboration with families. Q-SLPs felt that structured observation had great potential in facilitating collaboration by creating opportunities for communication partners training, similarly to previous research regarding video feedback (Damen et al., Citation2011).

Participants suggested that information from informant report, structured observation, and family discussions about priorities can be triangulated to achieve the most holistic client picture. This is in line with best practice, whereby ethical assessment requires the use of multiple tools (Brady et al., Citation2016). This is also consistent with existing assessment protocols, which stipulate that assessment should provide informant insight into the person’s behaviours as well as opportunity for observations and behaviour sampling (Ogletree et al., Citation1996). However, tensions arose when participants felt pressure to integrate families’ priorities, especially when these were in conflict with their own.

Meeting workplace demands

SLPs felt that families often prioritised intervention rather than assessment, which was also impacted by funding considerations. Tension arose when SLPs sought comprehensive information, but families desired efficiency. Participants therefore valued tools facilitating efficient assessment and expressed concerns about tools requiring greater time investment. Consistent with previous literature (Brady & Keen, Citation2016), participants valued informant reports’ efficiency in collecting meaningful information for goal planning. And while participants viewed structured observation as having potentially rich outcomes, it was perceived to require greater time investment, which has financial implications.

The implications of time and funding pressures suggest the need for a shift in the value ascribed to assessment, in supporting both clinicians and families to embrace ongoing, dynamic assessment that is neither conceptually nor practically separate from intervention (Boers et al., Citation2013). This concept is illustrated in , whereby dynamic assessment is contrasted with the traditional separation of assessment and intervention. This paradigm shift must adopt a top-down approach, from funding bodies and service providers, to enable effective knowledge translation that allows clinicians to freely abide by best practice principles, given evidence that appreciation of assessment by organisations, clinicians, and families then makes time a secondary factor in evidence-based assessment.

This study highlighted constraints regarding time and funding, consistent with other research identifying these as perennial barriers to clinicians’ implementation of evidence-based practice (EBP) despite otherwise positive attitudes towards EBP (Harding et al., Citation2014). It could be argued that herein lies the value of adaptive practice, whereby clinicians have flexibility to provide services without rigid budgets being specified for hours of assessment and hours for intervention. This then requires tools with adaptive potential, given that resource constraints will likely persist. Both informant report and structured observation tools possess this potential, in enabling efficient yet meaningful assessment.

Participants also experienced tension in managing workplace demands in integrating research, clinician, and client-based factors in their tool choice. Q-SLPs questioned funding providers’ emphasis on research-based evidence for intervention despite its paucity (Plante, Citation2004). This possibly links to the way assessment results (as a form of client evidence) and practice evidence (both their own and others’ experience) are perceived, despite participants suggesting that employing both is common practice, as in previous research (Dada et al., Citation2017). Participants implied the possible influence of these factors on their tool choice in practice, which could have otherwise been different.

Meeting clinicians’ profile of capabilities

Participants felt an additional pull towards tools matching their knowledge, skills, and experience and felt that their theoretical knowledge of assessment approaches and tools was critical in informing their choices. For instance, S-SLPs valued tools providing holistic insight, which mirrored their learning about holistic clinical practice. Therefore, participants viewed ongoing learning as critical to achieving best practice. However, they also recognised practical experience as essential.

Participants identified that working in disability required sophisticated skills, thinking, and consequently unique experience outside of “regular speech pathology,” to meet the complex support needs of individuals with disability. Specific to assessment, participants regarded quality assessment as being dependent on clinicians’ component skills including behaviour interpretation, the ability to transfer results into goals, and overall flexibility. As such, participants felt that useful tools needed to fit with clinicians’ skill level and identified that less-experienced clinicians would need tools with a higher degree of scaffolding. Participants recognised the value of an informant report’s structure and content in supporting novice clinicians, while structured observation might be more challenging given its reliance on knowledge and skill in the field. Participants’ skill level also impacted their perceived need for external support, the availability of which was also dependent on organisational priorities.

Participants alluded to the necessity of experience, as opposed to theory alone, in acquiring these skills. Consistent with SLP self-efficacy research (Pasupathy & Bogschutz, Citation2013), participants felt that experience was essential. Firstly, in establishing their confidence to choose tools they felt were best. Secondly, as in previous research (Chadwick et al., Citation2019), participants suggested that experience is necessary in using tools, particularly in goal planning. Although there exists evidence of skill transference from experiences in other areas of practice (Sheepway et al., Citation2014), there remains a case for disability-specific experience highlighted in this study, whereby disability-specific placements have led to greater confidence in disability practice (Karl et al., Citation2013), and ongoing training and experience facilitates competency in disability-specific contexts (Dietz et al., Citation2012; Hines & Lincoln, Citation2016). Participants raised a sense of tension in the need for, but limited opportunities for, experience as a result of time and funding constraints.

Implications

To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first qualitative study to explore clinicians’ perspectives on the clinical utility of informant report and structured observation tools in assessing the communication of people with severe intellectual disability, and also highlights new considerations for using structured observation in clinical practice. This study is a first step in meeting the need to understand clinicians’ rationales for assessment decisions in severe intellectual disability, where most existing research has employed quantitative methods including surveys or questionnaires (Chadwick et al., Citation2019; Dada et al., Citation2017; Lund et al., Citation2017; Rowland, Citation2011; Watson & Pennington, Citation2015).

The implications of this study relate to training and educational needs of both qualified and student SLPs, to create a workforce skilled enough to provide functional assessment leading to meaningful participation outcomes. The complexities of working in disability call for specialised training, to equip clinicians for assessment in the field. Q-SLPs’ comments suggest a gap in their training to work in a disability setting, whereas current S-SLPs reported a more robust emphasis on skills and principles necessary for functional assessment during their education. This is encouraging and should be continued, to ensure graduates have necessary skills to work with the disability population, but should also incorporate opportunities for practical experience.

Further, the current tensions faced in balancing funders’, families’, and their own priorities might cause stress for those choosing to work in the field, which may impact clinician recruitment, retention, and ultimately quality of service delivery (Hines & Lincoln, Citation2016). Funding providers must therefore consider systemic structures that encourage the valuing of assessment at an organisational level, to support clinicians in conducting assessment that achieves meaningful outcomes.

Limitations

This study was limited in its representativeness of clinician practice, in its somewhat artificial setup, whereby the participants did not meet the person but were provided with completed informant report tools and a short video. Clinicians noted that this study did not include physical engagement with clients to understand their priorities in planning fully functional goals, which was not possible given the need for standard research procedures. Secondly, the relatively small sample size of this study means that results cannot be generalised to represent the views of the clinician population in totality. Finally, despite all means to mitigate personal bias effects, researcher backgrounds could have influenced perspectives in data analysis.

Directions for future research

Future research could be conducted with larger participant numbers, to allow a greater and more balanced spread of views that are more representative of the clinician population. Future research utilising observational methodologies or retrospective interviews could also gain more realistic insights into clinicians’ real-world practices and decisions.

Conclusion

In conclusion, participants’ views on the utility of informant report and structured observation were greatly influenced by tensions between their desires, the realities of clinical practice, and their own capabilities. These influences had direct impacts on specific tool characteristics they valued. These findings have the potential to guide clinician decision-making in assessment, the creation of novel tools, as well as providing critical feedback to service and education providers on clinician needs for training and best practice in assessment.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Attride-Stirling, J. (2001). Thematic networks: An analytic tool for qualitative research. Qualitative Research, 1(3), 385–405. https://doi.org/10.1177/146879410100100307

- Birt, L., Scott, S., Cavers, D., Campbell, C., & Walter, F. (2016). Member checking: A tool to enhance trustworthiness or merely a nod to validation? Qualitative Health Research, 26(13), 1802–1811. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732316654870

- Bloomberg, K., West, D., Johnson, H., & Iacono, T. (2009). The triple C: Checklist of communicative competencies—revised. Victoria, Australia, Scope.

- Boers, E., Janssen, M. J., Minnaert, A. E. M. G., & Ruijssenaars, W. A. J. J. M. (2013). The application of dynamic assessment in people communicating at a prelinguistic level: A descriptive review of the literature. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 60(2), 119–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/1034912X.2013.786564

- Braddock, B. A., Bodor, R., Mueller, K., & Bashinski, S. M. (2017). Parent perceptions of the potential communicative acts of young children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 42(3), 259–268. https://doi.org/10.3109/13668250.2016.1235141

- Brady, N. C., Bruce, S., Goldman, A., Erickson, K., Mineo, B., Ogletree, B. T., Paul, D., Romski, M., Sevcik, R., Siegel, E., Schoonover, J., Snell, M., Sylvester, L., & Wilkinson, K. (2016). Communication services and supports for individuals with severe disabilities: Guidance for assessment and intervention. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 121(2), 121–138. 165-168. https://doi.org/10.1352/1944-7558-121.2.121

- Brady, N. C., Herynk, J. W., & Fleming, K. (2010). Communication input matters: Lessons from prelinguistic children learning to use AAC in preschool environments. Early Childhood Services , 4(3), 141–154. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3063120/

- Brady, N. C., & Keen, D. (2016). Individualized assessment of prelinguistic communication. In: Keen, D., Meadan, H., Brady, N., Halle, J. (eds.), Prelinguistic and Minimally Verbal Communicators on the Autism Spectrum (pp. 101–119). Singapore: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-0713-2_6

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Carroll, A., Houghton, S., Taylor, M., West, J., & List-Kerz, M. (2006). Responses to interpersonal and physically provoking situations: The utility and application of an observation schedule for school-aged students with and without attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Educational Psychology Review, 26(4), 483–498. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616710500342424

- Carter, S. M., & Little, M. (2007). Justifying knowledge, justifying method, taking action: epistemologies, methodologies, and methods in qualitative research. Qualitative Health Research, 17(10), 1316–1328. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732307306927

- Cascella, P. W., Trief, E., & Bruce, S. M. (2012). Parent and teacher ratings of communication among children with severe disabilities and visual impairment/blindness. Communication Disorders Quarterly, 33(4), 249–251. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525740112448249

- Chadwick, D., Buell, S., & Goldbart, J. (2019). Approaches to communication assessment with children and adults with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 32(2), 336–358. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12530

- Clarke, V., & Braun, V. (2017). Thematic analysis. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 12(3), 297–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2016.1262613

- Crais, E., Douglas, D. D., & Campbell, C. C. (2004). the intersection of the development of gestures and intentionality. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 47(3), 678–694. https://doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2004/052)

- Cunningham, B. J., Daub, O. M., & Cardy, J. O. (2019). Barriers to implementing evidence-based assessment procedures: Perspectives from the front lines in pediatric speech-language pathology. Journal of Communication Disorders, 80, 66–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcomdis.2019.05.001

- Dada, S., Murphy, Y., & Tönsing, K. (2017). Augmentative and alternative communication practices: a descriptive study of the perceptions of South African speech-language therapists. Augmentative and Alternative Communication), 33(4), 189–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/07434618.2017.1375979

- Damen, S., Kef, S., Worm, M., Janssen, M. J., & Schuengel, C. (2011). Effects of video-feedback interaction training for professional caregivers of children and adults with visual and intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 55(6), 581–595. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2788.2011.01414.x

- Dew, A., Collings, S., Dillon Savage, I., Gentle, E., & Dowse, L. (2019). Living the life i want’: A framework for planning engagement with people with intellectual disability and complex support needs. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 32(2), 401–412. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12538

- Dietz, A., Quach, W., Lund, S. K., & McKelvey, M. (2012). AAC assessment and clinical-decision making: the impact of experience. Augmentative and Alternative Communication), 28(3), 148–159. https://doi.org/10.3109/07434618.2012.704521

- Harding, K. E., Porter, J., Horne-Thompson, A., Donley, E., & Taylor, N. F. (2014). Not enough time or a low priority? Barriers to evidence-based practice for allied health clinicians. The Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, 34(4), 224–231. https://doi.org/10.1002/chp.21255

- Hines, M., & Lincoln, M. (2016). Boosting the recruitment and retention of new graduate speech-language pathologists for the disability workforce. Journal of Clinical Practice in Speech-Language Pathology, 18(2), 50–54.

- Iacono, T., West, D., Bloomberg, K., & Johnson, H. (2009). Reliability and validity of the revised Triple C: Checklist of communicative competencies for adults with severe and multiple disabilities.(Report). Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 53(1), 44–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2788.2008.01121.x

- Johnson, H., Douglas, J., Bigby, C., & Iacono, T. (2011). The challenges and benefits of using participant observation to understand the social interaction of adults with intellectual disabilities. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 27(4), 267–278. https://doi.org/10.3109/07434618.2011.587831

- Karl, R., McGuigan, D., Withiam-Leitch, M. L., Akl, E. A., & Symons, A. B. (2013). Reflective impressions of a precepted clinical experience caring for people with disabilities. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 51(4), 237–245. https://doi.org/10.1352/1934-9556-51.4.237

- Keen, D., Sigafoos, J., & Woodyatt, G. (2005). Teacher responses to the communicative attempts of children with autism. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 17(1), 19–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10882-005-2198-5

- Kiernan, C., & Reid, B. (1987). Pre-verbal communication schedule (PVCS) manual. Windsor, UK: NFER Nelson. available from https://www.mosaiccommunication.com.au/pvcs

- Lund, S. K., Quach, W., Weissling, K., McKelvey, M., & Dietz, A. (2017). assessment with children who need augmentative and alternative communication (AAC): Clinical decisions of AAC specialists. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 48(1), 56–68. https://doi.org/10.1044/2016_LSHSS-15-0086

- Lyons, G., De Bortoli, T., & Arthur-Kelly, M. (2017). Triangulated proxy reporting: A technique for improving how communication partners come to know people with severe cognitive impairment. Disability and Rehabilitation, 39(18), 1814–1820. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2016.1211759

- Meadan, H., Halle, J. W., & Kelly, S. M. (2012). Intentional communication of young children with autism spectrum disorder: Judgments of different communication partners. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 24(5), 437–450. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10882-012-9281-5

- Ogletree, B. T., Fischer, M. A., & Turowski, M. (1996). Assessment targets and protocols for nonsymbolic communicators with profound disabilities. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 11(1), 53–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/108835769601100107

- Ogletree, B. T., & Price, J. (2018). Nonstandardized evaluation of emergent communication in individuals with severe intellectual disabilities: exploring existing options and proposing innovations. Advances in Neurodevelopmental Disorders, 2(1), 38–48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41252-017-0043-3

- Pasupathy, R., & Bogschutz, R. (2013). An investigation of graduate speech-language pathology Students’ SLP clinical self-efficacy. Contemporary Issues in Communication Science and Disorders, 40(Fall), 151–159. https://doi.org/10.1044/cicsd_40_F_151

- Plante, E. (2004). Evidence based practice in communication sciences and disorders. Journal of Communication Disorders, 37(5), 389–390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcomdis.2004.04.001

- Porter, J., Ouvry, C., Morgan, M., & Downs, C. (2001). Interpreting the communication of people with profound and multiple learning difficulties. British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 29(1), 12–16. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1468-3156.2001.00083.x

- Rowland, C. (2011). Using the communication matrix to assess expressive skills in early communicators. Communication Disorders Quarterly, 32(3), 190–201. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525740110394651

- Sheepway, L., Lincoln, M., & McAllister, S. (2014). Impact of placement type on the development of clinical competency in speech–language pathology students. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 49(2), 189–203. https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12059

- Siegel-Causey, E., & Bashinski, S. M. (1997). Enhancing initial communication and responsiveness of learners with multiple disabilities: A tri-focus framework for partners. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 12(2), 105–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/108835769701200206

- Sigafoos, J., Woodyatt, G., Keen, D., Tait, K., Tucker, M., Roberts-Pennell, D., & Pittendreigh, N. (2000). Identifying potential communicative acts in children with developmental and physical disabilities. Communication Disorders Quarterly, 21(2), 77–86. https://doi.org/10.1177/152574010002100202

- Smart, A. (2006). A multi-dimensional model of clinical utility. International Journal for Quality in Health Care: Journal of the International Society for Quality in Health Care, 18(5), 377–382. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzl034

- Smidt, A. (2020). MOSAIC: A model of observational screening for analysis of interaction and communication. Andy Smidt. www.mosaiccommunication.com.au

- Tan, V., Smidt, A., Herman, G., Munro, N., & Summers, S. (2023). Revising the pragmatics profile using a modified delphi methodology to meet the assessment needs of current speech-language therapists. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 58(6), 2144–2161. https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12922

- Watson, R. M., & Pennington, L. (2015). Assessment and management of the communication difficulties of children with cerebral palsy: A UK survey of SLT practice. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 50(2), 241–259. https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12138