Abstract

The Chinese goal to reach carbon peak by 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality by 2060 (the “30/60” dual carbon goal) will require a swift and dramatic reduction in greenhouse gas emissions. Among various ocean carbon dioxide removal (CDR) technologies, seaweed cultivation has gained more attention due to its potential for CO2 removal. However, the current legal framework in China lacks specific laws and regulations addressing seaweed cultivation for carbon removal. This paper highlights three key points: (1) the existing Chinese legal system needs to be updated to keep up with policy changes and govern the practice of seaweed cultivation for carbon removal; (2) transitioning seaweed cultivation from aquaculture to an ocean CDR approach can promote climate mitigation benefits; and (3) successful implementation requires not only technical and financial support but also the establishment of comprehensive policy and legal frameworks.

Introduction

The earth’s climate and the oceans are interdependent [Citation1]. This relationship is explicitly acknowledged by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), recognizing the crucial role of the ocean in climate change mitigation. Article 4(1) of the UNFCCC emphasizes the commitment of all parties to promote sustainable management and collaborate in the conservation and enhancement of sinks and reservoirs of greenhouse gases, explicitly including the ocean and marine and coastal ecosystems [Citation2]. The ocean absorbs around 90% of the heat generated by rising greenhouse gas emissions trapped in the earth’s system and has taken roughly 30% of CO2 emissions [Citation3]. Moreover, the ocean’s photosynthetic activity carried out by marine plants and algae contributes to the production of approximately 50% of the earth’s oxygen [Citation4]. Consequently, a substantial portion of the global capacity for natural carbon sequestration relies upon the ocean’s indispensable function.

Based on a report by the International Energy Agency, the reduction of global CO2 emissions heavily relies on the actions taken by developing (non-OECD) countries [Citation5, Citation6]. Consequently, it is imperative for both developed and developing nations to collaborate in achieving the target of limiting global warming to 1.5–2 °C, as outlined in the 2015 Paris Agreement. This collaboration necessitates the implementation of nationally determined contributions (NDCs) set forth in the agreement. In its NDCs, China has made commitments to peak carbon dioxide emissions by 2030 and to attain carbon neutrality by 2060 [Citation7]. It is a great challenge for China to achieve the set goal of reducing emissions while pursuing socioeconomic development, and China has to use all options possible to reduce and avoid emissions, as well as adapt itself to climate change [Citation8].

Carbon dioxide removal (CDR) encompasses human activities aimed at extracting carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and storing it in geological, terrestrial, oceanic reservoirs, or even in the form of products [Citation9]. Ocean based CDR is a fluid category that currently encompasses several options, such as artificial upwelling, ocean fertilization, seaweed cultivation, ocean alkalinity enhancement, and restoration of vegetated coastal habitats [Citation10]. Given the vast extent of the ocean within China’s jurisdiction, a significant amount of CO2 could be stored through these approaches at sea. However, considering the feasibility, potential environmental impacts, costs and other factors, it is realized that not all ocean CDR technologies are popularly acceptable and/or implementable in China. Methods such as electrochemical ocean CDR approaches are relatively recent developments. Due to the absence of proof-of-concept field experiments, the assessment of associated benefits and risks has remained elusive thus far. A challenge lies in confirming the additional CO2 uptake from the atmosphere resulting from electrochemical CDR, given the ocean’s dynamic CO2 flux “background state”[Citation11]. Another approach, ocean fertilization, holds the potential for increased export of organic carbon to the deep ocean or the stimulation of harvestable macroalgae biomass, which can be utilized in other pathways for carbon storage [Citation12]. Whereas the sea areas with eutrophication in China were as large as 45,330 km2 [Citation13], the main cause of eutrophication is the excessive inorganic-N and active-P [Citation13]. In this case, whether the coastal waters of China are suitable to be fertilized still needs further studies, especially in the eutrophication sea areas. Unlike these methods, seaweed cultivation, a traditional marine industry in China, can become most optimal at present.

Currently, seaweed cultivation in China has primarily focused on food production, remaining a big potential to develop for the purpose to mitigate climate change. Against this background, this paper seeks to: (1) fill a research gap by providing an overview of the current policy and legal frameworks specifically related to seaweed cultivation in China. As there are limited literature or studies exploring the legal and policy aspects associated with this particular activity; (2) identify existing deficiencies in the current policy and legal frameworks governing seaweed cultivation in China, and then shed light on areas that require improvement, modification, or better enforcement. The paper contributes to enhancing the understanding of the challenges and limitations faced in the legal and policy frameworks for seaweed cultivation; (3) provide new solutions. By proposing new solutions or recommendations, the paper contributes to the development of innovative approaches for addressing the emerging issues associated with seaweed cultivation and its potential role in ocean CDR; and (4) provide valuable insights and references for policymakers involved in the formulation of policies and regulations regarding seaweed cultivation in China.

Advantages of seaweed cultivation for CDR in China

Seaweed cultivation encompasses the cultivation of kelp and other macroalgae, which has the potential to sequester CO2 through biomass uptake [Citation14]. In China, compared with other vegetated coastal ecosystems, e.g. mangroves, saltmarshes and seagrasses, seaweed cultivation has its unique advantage of carbon sequestration, geographical distribution, and mature farming technology. China dominates the global seaweed aquaculture sector, representing approximately 70% of its production [Citation15]. The large commercial algae are abundant in China, including saccharina japonica, undaria pinnatifida, porphyra yezoensis, and gracilaria lemaneiformis () [Citation16]. The country boasts a rich diversity of commercial macroalgae widely from Liaoning Province in the north to Hainan Province in the south [Citation17]. Seaweed farms cover 1,250 km2 along the Chinese coast, making up around 41% of all current blue carbon ecosystems (both natural and artificial), and their size is expanding quickly [Citation8]. Different from the wide growth range and rapid growth rate of seaweed, mangroves are found only in southeastern China and has quickly declined since the 1950 [Citation8, p. 3].

Table 1. China’s main seaweed species and their carbon content (wet weight).

In China, natural occurring mangrove, tidal saltmarsh, and seagrass ecosystems sequester 0.32–0.64 Tg of carbon each year [Citation8]. However, coastal development activities, such as land reclamation, industry, and urban construction, have caused the areas of tidal saltmarshes and mangrove forests to decline quickly [Citation8]. The production of seaweed for aquaculture, on the other hand, increased from 1.7647 million tons in 2012 to 2.7239 million tons in 2022 [Citation18]. The area of natural occurring seaweed in China is yet known, which makes it impossible to estimate its potential to sequester carbon at the national level [Citation8]. On the other hand, without distinguishing the carbon storage cycle timescales, the overall farmed seaweed carbon sinks in China increased from 0.96 to 1.41 Tg C/year during 2010 − 2019 (distinguishing between the carbon storage cycle timescales, the overall farmed seaweed carbon sinks in China increased from 0.54 to 0.72 Tg C/year in the same period) [Citation19]. It shows that the farmed seaweed carbon sinks in China are increasing, compared with mangrove, tidal saltmarsh, and seagrass. At present, large-scale seaweed cultivation occupies merely 0.3% of the coastal waters, indicating significant untapped potential and ample room for further expansion and development [Citation20]. However, incorporating seaweed cultivation into ocean CDR strategies for addressing climate change is debatable [Citation21]. Some scholars hold the view that the rapid turnover rate of seaweed biomass, whether natural or through multiple uses, imposes limitations on its long-term capacity to sequester carbon [Citation22]. Regardless, to maximize the climate change mitigation potential of seaweed aquaculture, it is imperative to utilize seaweed yield for various purposes, such as biofuel production and soil amendments through bioprocessing [Citation23]. Unfortunately, China currently lacks an industry dedicated to biofuel production derived from seaweed aquaculture or the development of long-lived products based on seaweed [Citation8, p.8].

Some countries are aware of the rise in the interest in the number of seaweed cultivation for carbon dioxide removal. The Netherlands is currently engaged in several seaweed cultivation projects, with the government aiming at large-scale growth and processing of seaweed [Citation24]. Seaweed farming has also taken off in recent years in Maine and Alaska, USA [Citation25]. As seaweed farming is a traditional industry in China, it has an inherent advantage using seaweed cultivation as a CDR technology in comparison with the above countries. The pressing task for China, though, is how to use seaweed production as both a food source and an ocean CDR approach.

Policies guiding seaweed cultivation as an ocean CDR approach

Policies for expanding the scope of blue carbon

The “14th Five-Year Plan for National Economic and Social Development of the People’s Republic of China and the Outline of Long-Term Goals for 2035” (the 14th Five-Year Plan) released in 2021 includes the “30/60” dual carbon goal. The important role of the marine ecosystem in achieving the “30/60” dual carbon goal should be indispensably valued.

The restoration of coastal vegetation is currently listed as a top priority under several national strategic objectives. In 2015, the State Council issued the National Marine Function Zoning, highlighting the crucial significance of proactively enhancing the role of marine carbon sinks. The document defined the sea areas of Shandong Peninsula, the northern part of Jiangsu Province, eastern Hainan Island, as “optimal developing zones” which prioritized the development of ecological aquaculture, protection of seagrass beds and expansion of marine ranching (also known as sea farming) [Citation26]. In 2017, the State Council and Party Central Committee jointly required the nation to set and enforce ecological redlines, particularly marine ecological redlines, and urged the process to be completed by the end of 2020 [Citation27]. The State Council has thus far accepted the proposed redlines from 15 coastal provinces. Furthermore, Secretary General Xi Jinping spoke at the 19th Congress of the Communist Party of China (18–24 October 2017), emphasizing the importance of joining international environmental initiatives to promote the restoration of coastal wetlands. Several initiatives have been created to put these policies into practice, and they include the reconstruction of “Blue Bay,” which is essential for CO2 removal, and the “Mangroves in the South and Tamarix Chinensis in the North” project. The protection, replanting, or management of mangroves, saltmarshes, and seagrass are all examples of “blue carbon” mitigation measures that China has incorporated into its NDCs [Citation7]. A nationwide blue carbon initiative is now being developed in China. The term “blue carbon” has been used in numerous significant documents, including the “13th Five-Year Plan for Controlling Greenhouse Gas Emissions,” “National Marine Main Function Zone Planning,” and “Opinions of the State Council and the CPC Central Committee on Accelerating the Construction of Ecological Civilization.” The key to enhancing the capacity of blue carbon sinks lies in reinforcing the effective conservation and restoration of blue carbon ecosystems, while also successfully expanding the scale of carbon sinks through seaweed aquaculture.

A total of 42 policy documents pertaining to blue carbon management have been identified between 2014 and 2021 [Citation28]. Among these, 24 policies were issued by the central government, and 18 were implemented at the local government level [Citation28]. However, the developing notion of blue carbon has not yet completely considered in the regulation of seaweed production for climate change mitigation by sequestering CO2 [Citation29]. The reason possibly lies in the belief that most of the seaweed output is broken down in the water, and it does not function as a net sink for CO2, [Citation29] while recent studies show that seaweed is an important global contributor to oceanic carbon sinks [Citation30]. Therefore, China’s national climate policies should reflect how seaweed aquaculture contributes to blue carbon and climate change mitigation.

Policies for the establishment of the trading mechanism and blue carbon standard system

The carbon emissions trading market, commonly referred to as the “carbon market,” represents a substantial institutional innovation that utilizes market mechanisms to effectively regulate and mitigate greenhouse gas emissions while promoting the growth of low-carbon economies [Citation31]. This market serves as a crucial tool in the implementation of China’s climate policy to achieve the “30/60” dual carbon goal. The pilot carbon emissions trading scheme (CETS) has been set up in Shenzhen, Guangzhou, Shanghai, Hubei, Chongqing, and Tianjin since 2013. These provinces/cities’ governments have established regional emissions quotas, local trading regulations, and the allocation of emissions permits to businesses operating within their respective administrative boundaries. For example, in Xiamen city, the first platform for trading blue carbon was established and at the Xiamen Carbon and Emissions Trading Center, a pilot program in Lianjiang County traded 15,000 metric tons (MT) of carbon credits for CNY 12 million [Citation32]. However, China’s blue carbon market remains in the pilot stage, and the lack of relevant experience has led to the lack of a system to support relevant implementation mechanisms.

To enhance carbon market regulation, the Chinese government issued the National Carbon Emissions Trading Market Construction Plan (Power Generation Industry) (2017), Measures for the Administration of Carbon Emissions Trading (for Trial Implementation) (2020), and a quota allocation plan for the initial implementation cycle of the national carbon market [Citation31]. A fundamental national carbon market system was established in 2021, accompanied by guidelines for accounting and reporting corporate greenhouse gas emissions, as well as three sets of management rules governing carbon emission rights, encompassing registration, trading, and settlement processes [Citation31].

On 16 July 2021, the national carbon market commenced its online trading operations. There were 2,162 power generation companies involved, collectively representing a cumulative CO2 emissions volume of 4.5 billion tonnes [Citation31]. China’s carbon market is the largest in the world, but the blue carbon sink standard system still remains blank. In August 2017, the “Opinions on Improving the Strategy and System of Main Function Areas” emphasized the need to explore the establishment of a “blue carbon standard system and trading mechanism.” The document called for an accelerated research effort towards developing an ocean carbon neutral accounting mechanism and methodology, and to establish corresponding methods and technologies, measurement steps and operation specifications, evaluation standards for blue carbon fingerprint, carbon footprint and carbon identification [Citation33]. In 2022, the Ministry of Natural Resources (MNR) released the Accounting Methods for Ocean Carbon Sink (HY/T0349-2022), which was officially implemented on 1 January 2023. This is China’s first comprehensive industry standard for blue carbon sinks. The Accounting Methods for Ocean Carbon Sink regulates the definition and category of “ocean carbon sink” which includes the mangroves, saltmarsh, seagrass bed, phytoplankton, macroalgae and shellfish [Citation34]. It systematically regulates the processes, contents, methods of blue carbon sink accounting work, establishes a methodological system suitable for blue carbon sink accounting in China, and fills the gap in industry standards for accounting methods in this field [Citation34, Art.4]. Besides, MNR formulated and released the Estimation Method of Maricultural Seaweed and Bivalve Carbon Sink-Carbon Stock Variation Method (HY/T 0305-2021) in 2021. This standard adopts the method of carbon stock change, which calculates the carbon sink amount of seaweed cultivation in one growth cycle by subtracting the initial carbon stock of seedlings from the carbon stock harvested by adult organisms, using conversion factors [Citation16]. Together with the Accounting Methods for Ocean Carbon Sink, it provides technical and methodological support for the accounting of seaweed carbon sinks in China.

Economic policies for seaweed farming

Development of seaweed farming as a strategy to address climate change would expedite the advancement of seaweed aquaculture in China, and thereby generate more blue carbon sinks. China’s seaweed aquaculture industry has attracted many listed enterprises and individual fishermen. Factory-type aquaculture developed rapidly, and the scale and intensity of the seaweed farming industry are gradually increasing, but at present, it is still dominated by small and middle-scale companies and individual fishermen. Unstable income, low financial input, insufficient scientific and technological support, and other factors deter farmers and investors from engaging in seaweed farming. It is thus necessary to provide diverse economic incentive-oriented policies to encourage seaweed farming.

Policies for financial support. To establish a normalized operation mode, encourage long-term funds such as venture capital, entrepreneurial investment, and equity investment in the field of blue carbon economy, and focus on supporting the research and development of key blue carbon technologies [Citation35]. Some coastal provinces/cities have acted on building a financial support mechanism for blue carbon, including seaweed cultivation. For example, Weihai City government has issued the blue carbon economic development action plan (2021–2025) which aims to bolster financial support for the growth of the blue carbon economy, and to encourage active involvement of financial institutions in its development. To achieve this, the plan seeks to establish a diverse and comprehensive financing mechanism [Citation35].

Policies for private capital input. Encouraging private capital input for seaweed cultivation projects aims not only to provide financial support for enlarge its climate services functions, but also to show the economic, environmental, and social benefits of blue carbon projects, so as to attract social capital investment. This policy has already been adopted by other countries. For example, in July 2022, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and the Australian government’s Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment jointly established the world’s first Blue Carbon Accelerator Fund (BCAF) [Citation36]. This fund aims to provide assistance in two key areas: (a) facilitating project developers in preparing their initiatives for implementation and attracting future private sector financing, and (b) supporting on-the-ground projects focused on blue carbon ecosystem restoration or conservation that will serve as demonstration sites, showcasing and quantifying climate, biodiversity, and livelihood benefits while strengthening the business case for private sector investment in coastal blue carbon ecosystems [Citation36].

In addition to developing these policies for encouraging seaweed cultivation, another key issue is making the project developers, especially small and middle-scale companies, and individual fishermen, aware of the benefits of addressing seaweed cultivation as an ocean CDR approach.

Laws governing seaweed cultivation as an ocean CDR approach

Marine environmental protection legal framework

In accordance with the Law on the Administration of the Use of Sea Areas, it is a necessity to obtain permission to conduct seaweed cultivation projects within China’s jurisdiction [Citation37]. Additionally, adherence to national marine functional area planning, marine functional zoning, and relevant national environmental protection standards, as outlined by the Marine Environmental Protection Law (MEPL) and other applicable regulations, is essential for seaweed cultivation [Citation38]. Furthermore, seaweed cultivation projects in China must adhere to the Fisheries Law [Citation39]. According to this law, any individual or entity seeking to utilize water areas or tidal flats for seaweed cultivation must apply to the local government’s fisheries administrative department at or above the county level [Citation39, Art.11]. Priority should be given to local fishery workers when issuing aquaculture permits [Citation39, Art.12]. During seaweed cultivation, no noxious or harmful bait or feed is allowed [Citation39, Art.19]. Furthermore, prior to commencing the project, the project developer is required to prepare a marine environmental impact (EIA) report and submit it to the Ministry of Ecology and Environment (MEE) for review and approval [Citation38]. The EIA is the essential condition for getting the right to use sea areas and aquaculture permits.

Some existing rules are applicable to seaweed cultivation, but they just treat seaweed cultivation as an aquaculture activity without considering any factor of climate change mitigation, i.e. as a carbon dioxide removal approach, thus ignoring the linkage between climate change mitigation and marine environmental governance. At present, China’s legal framework for marine environmental protection is currently established on the foundation of the Constitution, supported by key environmental laws such as the Environmental Protection Law (EPL), Marine Environmental Protection Law (MEPL), Fisheries Law, and Island Protection Law. This comprehensive set of legislation, accompanied by administrative regulations, local rules, and regulations specific to marine areas, furnishes the legal basis for the effective utilization, protection, and management of marine environment and resources. It is worth examining them to see whether the climate factor has been considered.

The EPL acts as the cardinal law of environmental protection in China. As defined in Article 2 of EPL, the term “environment” encompasses both natural and artificially transformed natural elements that influence human existence and development. This broad definition includes the atmosphere, water bodies, seas, land, minerals, forests, grasslands, wildlife, natural and human-made structures, nature reserves, historical sites, scenic spots, as well as urban and rural areas [Citation40]. Therefore, the principles, regulations and legal responsibilities and other important elements stipulated in the EPL are applicable to marine environmental protection and climate change mitigation. For example, Article 40 emphasizes the value of clean production and resource recycling, and stresses importance of facilities and processes that facilitate efficient resource utilization while minimizing pollution discharge [Citation40, Art.40]. While the EPL establishes fundamental principles for safeguarding the natural environment and addressing pollution, it does not explicitly mention climate change and its impacts, nor regulation of carbon dioxide removal matters. A similar legal phenomenon also exists in other relevant legal instruments, e.g. MEPL.

From the above, we can see that current Chinese marine environmental protection laws do not take climate change into account, although some provisions are indirectly related. Climate change should be a necessary consideration in the formulation of future environmental laws and regulations. Towards that end, these legal frameworks should incorporate more targeted measures to address climate change, including specific regulations pertaining to seaweed cultivation as a crucial approach for ocean CDR.

Laws for blue carbon market

At present, China has only two legal instruments pertaining to carbon trading. These include the 2020 Interim Measures on Carbon Emissions Trading Management, issued by the MEE, which governs the operation of the national unified mandatory carbon market. The second instrument is the 2012 Interim Measures for the Management of Greenhouse Gas Voluntary Emission Reduction, which provides guidance for the voluntary carbon market. However, the “blue carbon sink” is not clearly included in these two legal instruments. For example, Article 42 of the Interim Measures on Carbon Emissions Trading Management defines China Certified Emission Reduction (CCER), which refers to the greenhouse gas emission reduction of renewable energy, forestry carbon sinks, and methane utilization that is quantified and certified, and registered in the national greenhouse gas voluntary emission reduction trading registration system [Citation41]. CCER projects typically fall into two categories: one is for reducing carbon emissions by replacing fossil fuel-based energy with renewable sources like wind and solar power, and the other focused on CO2 absorption from the atmosphere through methods such as forestry carbon sinks and carbon capture, utilization, and storage technology (CCUS) [Citation42]. Unfortunately, whether the blue carbon sink is included in the CCER is not clearly known. In practice, CCER pilot projects were implemented across nine provinces and cities, namely Beijing, Tianjin, Shanghai, Hubei, Chongqing, Sichuan, Guangdong, Shenzhen, and Fujian. Each pilot region has imposed limitations on the types of CCER emission reductions, with a predominant focus on rural biogas and forestry carbon sink projects [Citation42]. To integrate blue carbon sink trading into the national unified carbon market, it is important to acknowledge the compliance function and circulation status of carbon offset credits generated by blue carbon sink projects, in addition to carbon allowances. Furthermore, the Interim Measures for the Management of Greenhouse Gas Voluntary Emission Reduction should then be amended to recognize the statutory positioning of blue carbon sink projects into the voluntary emission reduction trading system by listing them within the candidate range of eligible voluntary emission reduction projects.

China has encouraged emission reductions generated by forest-based green carbon sink projects for a while and formed a more matured management system, which could be a model pathway for the protection of blue carbon sinks including seaweed cultivation. For example, “the Interpretation of the Supreme People’s Court on Several Issues concerning the Application of Law in the Trial of Civil Disputes over Forest Resources,” which was released on 14 June 2022, applies the rules of forestry carbon sink trading [Citation43]. This judicial interpretation clarifies that for the new type of guarantee that takes forestry carbon sinks as the object, the court will protect the priority right of the security holder in accordance with the law adhering to the principle of legal property rights [Citation43, Art.16]. Besides, it also allows the parties to subscribe certified forestry carbon sinks as an alternative to fulfill the responsibility for damage compensation of the forest ecological environment [Citation43, Art.20]. With the development of blue carbon trading and the increase of civil disputes over blue carbon resources, the issuing of a similar judicial interpretation will be a way to promote the effective restoration of the blue carbon ecological environment by flexibly using various methods of assuming responsibility, such as ecological restoration, damage compensation, subscription of blue carbon sinks, and labor compensation.

Legislation on climate change

The Chinese government’s response to climate change is an essential part of its overall endeavors to achieve environmental sustainability and promote high-quality development. To combat climate change, China has made progress in preparing a law aligned with the principles of sustainable development. A milestone was reached on 27 August 2009 when the National People’s Congress of China (NPC) Standing Committee adopted the Resolution on Actively Responding to Climate Change. This Resolution, representing the first of its kind adopted by China’s highest legislative body, acknowledges the importance of actively addressing climate change in the context of China’s overall economic and social development, as well as the immediate welfare of its citizens. Furthermore, in 2012, the Institute of Law of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences drafted “The Law of the People’s Republic of China on Climate Change Response (Draft Proposal)” which was subsequently submitted to the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) [Citation44].

The Draft Proposal contained 10 chapters in dealing with responsibilities, rights, and obligations in respect of addressing climate change, measures of mitigating and adapting to climate change, supervision and management, campaigning and education activities, and public participation, legal liabilities, and so on [Citation45]. This provides a legislative opportunity to incorporate the legal concept of “blue carbon” and related rules at the national level. Unlike existing laws and regulations, the Draft Proposal recognizes the important contribution of the ocean in climate change mitigation. Notably, it highlights the responsibility of the national marine management administrative department and coastal governments to enhance the protection of marine and coastal ecosystems, promote the establishment of marine protected areas, and strengthen the capacity of marine and coastal carbon sinks.” [Citation45] The term “carbon sinks” within the context of the Draft Proposal refers to various entities or locations such as trees, forests, soil, marine environment, facilities, or sites that effectively capture and store CO2 or other greenhouse gases, thereby reducing their release from emission sources [Citation45]. In addition, the Draft Proposal places significant emphasis on the implementation of comprehensive economic, technological, legal, and administrative measures to ensure effective capacity building in addressing climate change. For instance, it highlights the necessity for local governments at all levels to establish government climate change funds, which can be financed through government grants, carbon taxes, fees from greenhouse gas emissions allowances, social contributions, and other sources [Citation45]. The funds shall be utilized for various purposes, including climate change awareness and education, science and technology R&D, technology and product demonstration and extension, financial incentives for energy conservation, execution of major climate change projects, emergency responses to extreme weather events, industrial transformation, and reward [Citation45]. All these safeguard measures will apply to ocean CDR approaches when they become law in future.

Unfortunately, the Draft Proposal has not become a formal legal document yet. From the current content of the Draft Proposal, it basically serves as a framework law with relatively limited implementability. However, within the entire legal framework for addressing climate change, the future Law of the People’s Republic of China on Climate Change Response should be a foundational, comprehensive, and guiding legislation [Citation46]. It is expected to provide guidance not only for national efforts in addressing climate change and local climate change legislation, but also to play a integrating role in relation to relevant laws and regulations, such as the Renewable Energy Law, Energy Conservation Law, Clean Production Law, which contain provisions related to climate change.

China’s position concerning this legal development is consistent with its continuing climate change mitigation efforts, which have largely been driven by domestic concerns - energy demand and security, environmental deterioration, and economic transformation, as well as the need to maintain a responsible international image [Citation47]. On the other hand, as a party to the UNFCCC, Kyoto Protocol and the Paris Agreement, China must fulfill its treaty obligations under these international legal instruments. Due to climate change itself being a complex issue, response to such a multifaceted problem requires a multidimensional legal regime. The “Climate Change Response Law” will be a general legal framework for addressing climate change including ocean CDR approaches such as seaweed cultivation.

Coordination among relevant administrative departments

In China, the State Council represents the Central Government and exercises ownership rights over internal waters, territorial sea, underlying seabed, and subsoil [Citation37, Art.3]. Anyone who intends to conduct activities involving the continued use of a certain sea area exclusively for more than three months needs to apply for approval from the department in charge of marine administration under the people’s government at a level equal to or higher than the counties (i.e. the provinces/cities/counties level) [Citation37]. Different provinces have different regulations governing authorization. Generally, the department in charge of marine administration must examine applications, solicit opinions from the departments concerned, e.g. fishery administration, maritime authority at the same level [Citation37, Arts. 7, 17]. As the representative of the State, the State Council also exercises exclusive jurisdiction rights in the exclusive economic zone (EEZ) and continental shelf [Citation48]. To construct, operate, or utilize installations and structures within the EEZ or on the continental shelf, or engage in drilling activities on the continental shelf, individuals or entities are required to obtain approval from the MNR [Citation48, Arts. 7, 8]. Therefore, seaweed cultivation, according to the size of the sea area, must obtain approval from a competent department in charge of marine administration, which is administrated by the MNR of the State Council.

As mentioned above, anyone who wishes to conduct seaweed cultivation must conduct EIA and prepare the EIA report, which is the foremost step of applying for the right of sea use. In practice, the MEE assumes responsibility for managing the EIA process. In addition, anyone who wishes to utilize water areas or tidal flats for seaweed cultivation must apply to the administrative department for fisheries under the local people’s government at or above the counties level, which is supervised by the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs (MARA) to obtain the aquaculture permit [Citation38, Art.11].

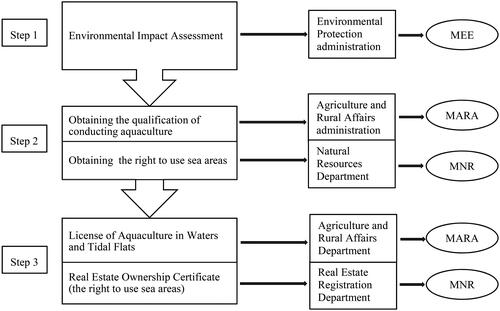

We can see that seaweed cultivation in China must go through at least three procedures, i.e. EIA, obtaining the right to use sea areas, and the qualification of conducting aquaculture, while each of them is administrated by different departments of the government (see ). Before 2018, the State Oceanic Administration (SOA) was in charge of formulating the systems and measures to enforce ocean-related laws and regulations, and monitoring the legal compliance of sea area uses, the protection of the marine environment, the exploration and utilization of marine mineral resources, as well as marine scientific research activities. Nevertheless, a governmentwide reform plan released on 19 March 2018 announced a “State Council Institutional Reform Plan” that ordered an extensive restructuring of the central government, among which, the MNR was formed to take on the responsibilities of the now-defunct SOA [Citation49]. The MNR oversees formulating strategies for marine economic development, marine resources utilization, and marine ecological restoration. Meantime, the MEE was formed to take on the responsibility of marine environmental protection of the now-defunct SOA [Citation49].

Figure 1. Related government administration for seaweed cultivation.

Source: Prepared by the authors.

Detailed departmental division, as well as multiple decentralized management systems, is conducive to carrying out comprehensive supervision of maritime activities, but may also produce the phenomenon of shifting responsibilities between departments, which does not improve the efficiency of the management of maritime activities. Besides, complicated procedures aggravate the burden of project applicants. Seaweed cultivation may act as an example to explain this issue. As mentioned above, conducting seaweed cultivation must obtain the right to use sea areas which is administrated by the local Natural Resources Department, and the qualification of conducting aquaculture which is administrated by the local Agriculture and Rural Affairs Department. The nature of these two rights is different. The purpose of issuing a certificate of the right to use sea areas is to clarify the type of sea use and the form of sea use, the identity of the user, skills, and funds are generally not considered in the examination and approval [Citation50]. While the License of Aquaculture in Waters and Tidal Flats is issued to clarify the content of the sea use, focusing on the review of the qualifications, capabilities, and skills of a farmer [Citation50].

The right to aquaculture and the right to sea use are two different management systems that regulate seaweed cultivation, which will lead to several problems in practice. In addition to the complicated administrative procedures for the applicants, the multiple administrative authorities in the supervisory process also cause troubles. MNR, MEE, and MARA have multiple-sector responsibilities, including the management of marine environmental pollution. Since there exists an overlap of jurisdictions on marine pollution matters during the aquaculture process, the concern arises as how to effectively address marine environmental protection in a unified and coordinated manner, while preventing administrative authorities from shifting responsibility to one another. To enhance legislative coordination and mitigate conflicts among different ministries, the State Council released updated regulations on 2nd June 2018. These regulations aim to facilitate smoother collaboration and introduce third-party evaluations for critical legislative matters that engender controversy among ministries [Citation51]. Nonetheless, this represents an initial step, and the smooth ministerial coordination and communication continue to be a long-term challenge [Citation52].

Furthermore, the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) is responsible for promoting the effective implementation of sustainable development strategies, advancing the construction and reform of ecological civilization, and coordinating efforts to foster energy conservation, environmental protection, and the development of clean production and other green industries [Citation53]. It is worthy to note that undertaking specific work on carbon peaking and carbon neutral, and response to climate change falls into the range of NDRC’s function. It is suggested that the NDRC take the lead in establishing a unified authority, such as a “comprehensive working group” or “joint approval working group” with MNR, MEE, MARA and other related departments, specializing in the approval and management of seaweed farming and other ocean CDR projects. This will be more cost-effective, more bureaucratic efficient, and more friendly to project applicants.

Conclusion

China’s commitment to achieving carbon neutrality by 2060 will contribute to a 0.2–0.3 °C reduction in global warming over the century, and therefore its roadmap for carbon neutrality is catching global attention. The current international focus is on the pathways and strategies to mitigate carbon emissions. However, in order to effectively achieve the goal of carbon neutrality, it is equally imperative to not only reduce carbon emissions but also enhance the capacity for CO2 absorption, i.e. the development and implementation of CDR technologies, to ensure sustainable economic development. Promoting large-scale seaweed cultivation as a model for ocean carbon dioxide removal (CDR) represents an efficient approach to achieve carbon neutrality within China’s coastal areas. Establishing extensive seaweed carbon sinks is an important pathway for reducing CO2 emissions and other greenhouse gases, fostering the development of a low-carbon marine economy, and attaining carbon neutrality. However, China’s existing institutional structure and legal system do not adequately account for seaweed production as a strategy for climate change mitigation and adaptation. While certain laws and regulations are applicable to seaweed cultivation, there is a need for more specific guidelines to effectively govern such activities in the future. Additionally, addressing the coordination of relevant government agencies, clarifying their responsibilities, and aligning their interests are pressing concerns in China. Establishing a unified authority for managing ocean CDR projects may be a necessary task in a long run.

Acknowledgments

This paper is partially funded by Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, China; No.3132023531.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Johansen E. The role of the oceans in regulating the earth’s climate: legal perspectives. In the law of the sea and climate change: solutions and constraints, Elise Johansen, Signe Busch, and Ingvild Ulrikke Jakobsen (eds.), New York: Cambridge University Press, 2020, p. 1.

- UNFCCC, Article 4 (1) (d), 1992.

- Subsidiary Body for Scientific and Technological Advice of UNFCCC. Ocean and climate change dialogue to consider how to strengthen adaptation and mitigation action. Available at https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/SBSTA_Ocean_Dialogue_SummaryReport.pdf.

- Hoegh-Guldberg O, et al. The ocean as a solution to climate change: five opportunities for action. Word Resources Institute, Washington, DC, USA, 2019, p. 5.

- Based on IEA data from World Energy Outlook 2014, OECD/IEA 2014, IEA Publishing; modified by the Global CCS Institute, 2014.

- Sun H, Samuel CA, Kofi Amissah JC, et al. Non-linear nexus between CO2 emissions and economic growth: a comparison of OECD and B&R countries. Energy. 2020;212:118637. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2020.118637.

- China’s Intended Nationally Determined Contribution. Available at https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/NDC/2022-06/China’s%20Achievements%2C%20New%20Goals%20and%20New%20Measures%20for%20Nationally%20Determined%20Contributions.pdf.

- Wu J, Zhang H, Pan Y, et al. Opportunities for blue carbon strategies in China. Ocean Coastal Manage. 2020;194(1):105241. doi:10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2020.105241.

- Shukla PR, Skea J, Reisinger A, et al. Climate change 2022: mitigation of climate change, summary for policymakers. Contribution of working group III to the sixth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, 2022. p. 36.

- Lezaun J. Hugging the shore: tracking marine carbon dioxide removal as a local governance problem. Front Clim. 2021;3:1. doi:10.3389/fclim.2021.684063.

- Ocean Visions, Development Gaps and Needs of Electrochemical Ocean CDR Technologies. Available at https://oceanvisions.org/roadmaps/electrochemical-cdr/development-gaps-and-needs/#addressingknowledgegaps.

- Wallace D, et al. Ocean Fertilization: a Scientific Summary for Policy Makers. IOC/UNESCO, Paris, 2010, available at http://www.igbp.net/download/18.1b8ae20512db692f2a680004381/1376383081959/oceanfertilization.pdf.

- Ministry of Ecology and Environment. Bulletin of China Marine Ecological Environment Status 2020. May 2021. Available at http://www.mee.gov.cn/hjzl/sthjzk/jagb/202105/P020210526318015796036.pdf.

- Babiker M, Berndes G, et al. Climate change 2022: mitigation of climate change. Contribution of working group III to the sixth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, 2022. p. 1273.

- FAO. The state of world fisheries and aquaculture 2016. Contributing to food security and nutrition for all. Rome, 2016, pp. 40–41.

- The industry standard Estimation Method of Maricultural Seaweed and Bivalve Carbon Sink-Carbon Stock Variation Method (HY/T 0305-2021), Article 4.1, 2021.

- Gao G, Gao L, Jiang M, et al. The potential of seaweed cultivation to achieve carbon neutrality and mitigate deoxygenation and eutrophication. Environ Res Lett. 2022;17(1):014018. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/ac3fd9.

- Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of the People’s Republic of China. National Fishery Economic Statistical Bulletin, available at http://www.yyj.moa.gov.cn/yqxx/202306/t20230628_6431131.htm and http://www.moa.gov.cn/xw/bmdt/201904/t20190418_6194415.htm.

- Liu C, Liu G, Casazza M, et al. Current status and potential assessment of china’s ocean carbon sinks. Environ Sci Technol. 2022;56(10):6584–6595. doi:10.1021/acs.est.1c08106.

- Yang Y, Luo H, et al. Large-scale cultivation of seaweed is effective approach to increase marine carbon sequestration and solve coastal environmental problems. Bull Chin Acad Sci. 2021;36(3):11. [in Chinese]

- Yong WTL, Thien VY, Rupert R, et al. Seaweed: a potential climate change solution. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2022;159:112222. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2022.112222.

- Troell M, Henriksson PJG, Buschmann AH, et al. Farming the ocean - seaweeds as a quick fix for the climate. Rev Fish Sci Aquacult. 2023;31(3):285–295. doi:10.1080/23308249.2022.2048792.

- Lian Y, Wang R, Zheng J, et al. Carbon sequestration assessment and analysis in the whole life cycle of seaweed. Environ Res Lett. 2023;18(7):074013. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/acdae9.

- Scott A. How the Netherlands is building a seaweed industry. Available at https://cen.acs.org/environment/sustainability/Netherlands-building-seaweed-industry/97/i34.

- NOAA Fisheries. Training builds on growing popularity of kelp farming. Available at https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/feature-story/training-builds-growing-popularity-kelp-farming.

- National Marine Function Zoning. Available at http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2015-08/20/content_10107.htm.

- Opinions on Drawing and Guarding Ecological Redlines. Available at http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2017-02/07/content_5166291.htm.

- Yu J, Wang Y. Evolution of blue carbon management policies in China: review, performance and prospects. Climate Policy. 2022;23:2.

- Duarte CM, Wu J, Xiao X, et al. Can seaweed farming play a role in climate change mitigation and adaptation? Front Mar Sci. 2017;4:2. doi:10.3389/fmars.2017.00100.

- Krause-Jensen D, Duarte CM. Substantial role of macroalgae in marine carbon sequestration. Nature Geosci. 2016;9(10):737–742. doi:10.1038/ngeo2790.

- Responding to Climate Change: China’s Policies and Actions. Available at http://english.scio.gov.cn/whitepapers/2021-10/27/content_77836502_4.htm.

- China Completes First Carbon Credits Trade from Aquaculture Sequestration Pilot. Available at http://sthjt.fujian.gov.cn/zwgk/sthjyw/stdt/202109/t20210915_5689069.htm.

- Bai Y, Hu F. Research on china’s marine blue carbon trading mechanism and its institutional innovation. Sci Technol Manage Res. 2021;3:189.

- The industry standard Accounting methods for ocean carbon sink (HY/T0349-2022), Article 3, 2022.

- Weihai City blue carbon economic development action plan (2021-2025). Available at http://www.weihai.gov.cn/art/2022/1/14/art_51909_2784002.html.

- New Blue Carbon Accelerator Fund to Support Blue Carbon Entrepreneurs and Leverage Private Sector Finance. avaiLable at https://www.iucn.org/news/marine-and-polar/202111/new-blue-carbon-accelerator-fund-support-blue-carbon-entrepreneurs-and-leverage-private-sector-finance.

- Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Administration of the Use of Sea Areas, Art. 16, 2001.

- Marine Environmental Protection Law, Art. 47, 2023.

- Fisheries Law of the People’s Republic of China, Art. 2, 2004.

- Environmental Protection Law, Art. 2, 2023.

- Interim Measures on Carbon Emissions Trading Management, Art. 42, 2014.

- China Development Brief. How Does China’s Certified Emission Reduction System Work? Available at https://chinadevelopmentbrief.org/reports/how-does-chinas-certified-emission-reduction-system-work/.

- The Interpretation of the Supreme People’s Court on Several Issues concerning the Application of Law in the Trial of Civil Disputes over Forest Resources. Available at https://www.court.gov.cn/zixun-xiangqing-362311.html.

- China Starts the Legislation of Climate Change Law. Available at http://www.cma.gov.cn/2011xzt/2012zhuant/20120612/2012061203/201204/t20120412_3101259.html.

- The Law of the People’s Republic of China on Climate Change Response (Draft Proposal). Available at http://www.china.org.cn/environment/2012-03/31/content_25035673.htm.

- Cao M, Zhang T. Progress and suggestions on climate change legislation. China Environ. 2020;4:31. [in Chinese]

- Zhao Y, Lyu S, Wang Z. Prospects for climate change litigation in China. TEL. 2019;8(02):349–377. doi:10.1017/S2047102519000116.

- The Law on the Exclusive Economic Zone and the Continental Shelf, Art. 15, 1998.

- Plan for Institutional Reform of the State Council. Available at http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2018-03/17/content_5275116.htm.

- The application materials for the right to use sea areas includes: (a) application form; (b) territorial Boundary site plan and territorial location plan (must be issued by a qualified institution with marine mapping); and (c) credit information (copy of identity certificate and organization code). available at http://zrzyj.zhuhai.gov.cn/zwgk/gzdt/content/post_2541049.html.

- Rules of the State Council. 25 June 2018, Available at http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2018-07/02/content_5302908.htm.

- Wang J, Zou K. China’s efforts in marine biodiversity conservation: recent developments in policy and institutional reform. Int J Marine Coastal Law. 2020;35:420.

- Main Functions of the NDRC. Available at https://en.ndrc.gov.cn/aboutndrc/mainfunctions/.