Abstract

This essay follows animals from the animal house through the laboratory to their representation as abstracted knowledge circulating the world to trace the emergence of experimental biology in Republican China. Experimental biology was promoted and institutionalized by the Chinese Physiological Society, which British-Chinese experimental physiologist Robert Lim established in 1926, at a time when descriptive taxonomy and morphology were dominant. Proponents argued that experimental research on live animals was more advanced than the collection and observation of specimens, and that experimentation, rather than description, now undergirded international science. In championing experimentalism, they were not only trying to shift the focus of Chinese biology from description to experiment, but also revising the scientism by then entrenched in Republican China. They put forth a scientism of experiment: cultivating experimental biology would help China catch up more quickly to imperial powers. Animals, as the material basis for experimental biology, came to signify the science that they produced; the Buddhist-aligned Chinese Animal Protection Society, established in 1932, chose not to protest animal experimentation in part due to the association between animals and modern experimentalism. In Republican China, animals were thus material and cultural objects that made and embodied a new scientism of experiment.

The Peking Union Medical College 北京協和醫學院 (PUMC) sat in the heart of Republican Peking. Amid the hustle and bustle of the city, the most prominent research institution in the country—the “Johns Hopkins of China” established and funded by the Rockefeller Foundation in 1906—took up one block.Footnote1 The compound consisted of a teaching hospital, dormitories for researchers and staff, and laboratories dedicated to clinical medicine, pharmacology, and pathology, as well as physiology. And mixed in with the sound of gossiping patients, shouting physicians, and rumbling ambulance trucks was the incessant barking of dogs.Footnote2 For by 1934, the College contained at least three animal houses, teeming not just with dogs, but also cats, rats, mice, rabbits, guinea pigs, and other experimental animals—even the occasional exotic creature, including, once, a camel.Footnote3

This essay follows animals from the animal house through the laboratory to their representation as abstracted knowledge in journal articles and conference presentations to trace the emergence of experimental biology in Republican China. The Chinese Physiological Society 中國生理學會 (CPS), the first Chinese organization dedicated to experimental biology, provided the material, intellectual, and institutional support for the science to take hold in the country. The CPS was established by British-Chinese Robert Kho-seng Lim 林可勝 in 1926 and operated largely out of the PUMC, which was able to provide financial resources and draw the attention of foreign scientists, given its Rockefeller Foundation ties. With such support, the Society cultivated not only experimental physiology—despite its name—but also biochemistry and pharmacology. In all three fields, animals were crucial research material. Scientists went through innumerable animals for vivisections, nutritional studies, and drug tests. To track animals as they were used to produce experimental knowledge is thus also to track the making of that knowledge.

The CPS nurtured experimental biology at a time when “descriptive” morphology 形態學 and taxonomy 分類學 dominated Chinese life sciences. Training and funding were almost completely concentrated in those two fields. The relative marginality of experimental biology—a situation that eases in the period this essay covers—has been replicated in the historiography of Chinese life sciences, which has almost completely focused on descriptive biology.Footnote4 As these histories have shown, biological research in this period was inseparable from the anti-imperialist conviction that modern science could “save China,” which had since the late nineteenth century suffered from a string of military defeats and unequal treaties (Wang Citation2002). This faith was part of a broader adherence to scientism among Chinese elites, who believed that science could modernize Chinese thought and culture to help their country catch up to Western imperial powers (see Kwok Citation1965; Shen Citation2016).

Scientism was entrenched in Republican China. However, the science that proponents championed was not stable nor homogenous; historians of modern Chinese science have increasingly emphasized the plurality and mutability of both science and scientism (see Seow and Lei Citation2022). In this essay, I show how biologists turned to scientific method to draw a distinction between competing forms of scientism.Footnote5 After elites had promoted science in general for decades, some researchers began to delineate particular approaches to science. They specifically advocated experimentalism, recasting the terms of “science”—and with it, scientism. These scientists distinguished between descriptive and experimental methods and asserted that experimentation was more advanced than descriptive biologists’ observation and collection.Footnote6 More importantly, at a time when what counted as “science” was being consolidated and universalized into “Western science,” they contended that international science was now undergirded by experimentation (see Elshakry Citation2010). Developing the experimental biology that scientists in the United States and Europe practiced would help China progress more quickly than if biologists continued to focus on descriptive biology. To these scientists, conducting experimental research signaled equality with the powerful nations setting the terms of international science: fostering experimentalism had the potential to ameliorate China’s political problems. As they sought to make Chinese biology experimental, they also intervened in elite discourse about the modernization of China to put forth a scientism of experiment.

Animals were critical to this ambition. In contrast to descriptive biologists’ animals and plants—tied to the places they were collected—experimental animals severed knowledge from locality. They were technologies of abstraction. The knowledge produced from experiments on standardized animals kept in controlled facilities was ostensibly detached from the place it was produced; expressed in research articles, it travelled around the world as graphs, numbers, and chemical formulas.Footnote7 Animals, by making knowledge placeless, “stripped of all context and environmental variation,” allowed experimentalists to integrate into international science (Kohler Citation2002, 191). As the material basis for Chinese experimental biology, animals, I argue, were therefore also the material basis for the scientism of experiment. They made experimental biology possible in Republican China and, through it, reworked the “science” that was supposed to free China from imperial oppression. While historians have largely analyzed intellectual debates around scientism, attention to animals thus demonstrates its materiality. Experimentalists used animals to literally construct a new approach to scientific research and to illustrate the political implications of experimentation.

Even those outside the realm of scientific research recognized the political promise animals held. As animals were experimented on, they also came to signify the knowledge they produced. The country’s first animal protection organization—Chungkuo Paohu Tungwu Hui 中國保護動物會 (Chinese Animal Protection Society, CAPS)—was established in exactly this period when animal experimentation was becoming more widespread.Footnote8 Yet protectionists did not oppose the practice.Footnote9 There were many reasons for protectionists’ lack of engagement. But their ultimate aim with animal protection was to bring peace to China, and they may have chosen not to protest because animal experimentation could help them reach that goal. CAPS members saw animal protection as a means to engender human kindness. Encouraging people to be kinder to living creatures would mitigate the violence ravaging the world—including imperial violence toward China. And like other elites of the period, they believed that advancing science could alleviate the country’s political troubles. To challenge the use of animals that were the foundation for scientific progress would have contradicted their aim of political equality—and thus peace—between China and Western imperial powers. It was this specificity of Chinese scientism and political anxiety that led to the valorization of animal experimentation. In other words, the universality toward which experimentalists strived and animals embodied was internal to Chinese elites’ local negotiations about the country’s relation to the rest of the world.Footnote10 As both material and cultural objects, experimental animals mediated these deliberations.

In what follows, I do not provide a chronological account of the emergence of experimental biology in Republican China. Rather, I accompany animals from the animal house through the laboratory and into the world, as they provided the basis for a reworking of both science and scientism. Focusing on the CPS and its institutional base at the PUMC, I begin in the animal house. I illustrate in material terms how experimentalists revised an established scientism by tying their work to “universal science” and the modernization of China; the live animals they bred and maintained in specialized housing contrasted with the local flora and fauna of descriptive biologists. I then move to the laboratory to explore the ways experimentalists used animals to make their research placeless so that it could circulate the world in publications and conference presentations; standardizing and experimenting on animals abstracted research from place and bolstered experimentalists’ claims that their work was more advanced than descriptive biologists’. Lastly, I leave the immediate realm of scientists. I examine the absence of antivivisectionism among animal protectionists to demonstrate how experimental animals had become implicated in a culture of scientism. By following animals through these domains, I show that as scientists used animals to make Chinese biology experimental, they also used them to advance a scientism of experiment. Animal experimentation encapsulated far more than simply experiments on animals.

1 The Animal House

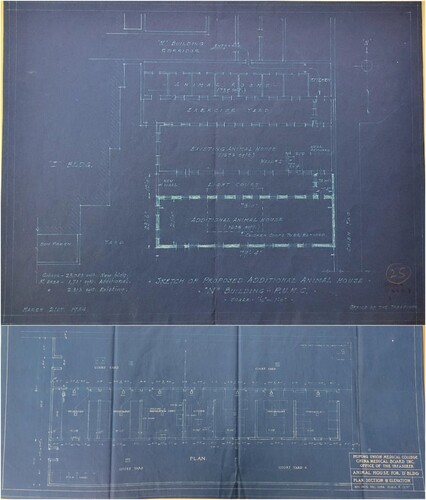

Throughout the 1920s and 30s, as research institutions across China controlled their budgets in a volatile political environment, PUMC administrators dedicated significant resources to experimental animals. Housing was a principal concern. The College organized a room circa 1920 to centrally maintain animals, which had previously been the responsibility of individual researchers. Soon thereafter, it constructed an animal house in the pathology and clinical department building. Yet that was far from enough. When Yale trustees visited in 1925, they were met with the sight and sound of yapping dogs overflowing into the corridors from the two animal rooms of the physiology and pharmacology building.Footnote11 In 1926—a year in which the College went through almost one thousand dogs—PUMC staff complained that without more space for animals, the research of the pathology and clinical divisions would “be very seriously hampered.”Footnote12 The urgency for animal housing was such that senior administration decided to enlarge the existing animal house and build an additional one without waiting for formal approval.Footnote13 And there were further expansions in 1934: a new building for small animals, another for dogs, and the establishment of a staff consisting of four animal feeders, three servants, a foreman, and a supervisor ().Footnote14 PUMC officials hastily renovated animal houses, as the built environment of the College simply could not keep up with the animals scientists needed.

Figure 1 1934 PUMC Animal house expansion. Top: Blueprint of animal house renovation in PUMC Building N.Footnote20 Bottom: Blueprint of animal house renovation in PUMC Building D.Footnote21 Courtesy of Rockefeller Archive Center.

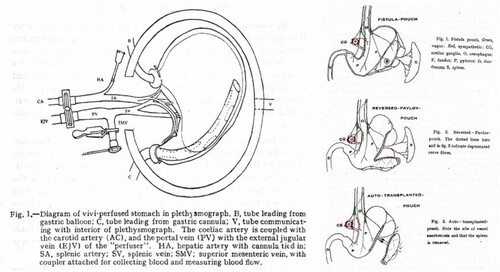

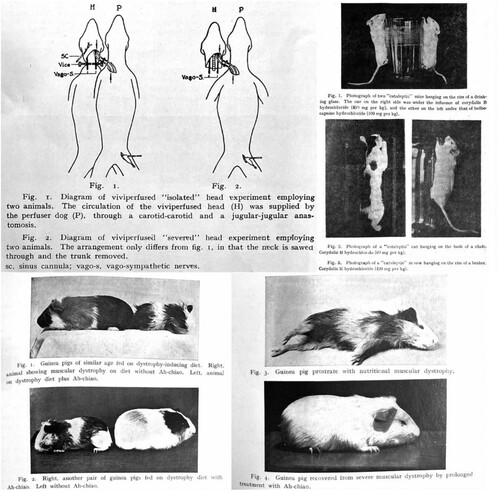

These animals and their care were a priority for the CPS, established by PUMC gastro-intestinal physiologist Robert Lim in 1926. He had trained at the University of Edinburgh with Edward Sharpey-Schafer and the University of Chicago with Anton J. Carlson and was recruited in 1924 to serve as Associate Professor and Chair of Physiology (he was promoted to full professor in 1927).Footnote15 Lim, who specialized in vivisections, used many animals in his research.Footnote16 Early experiments, for instance, involved transplanting gastric pouches from donor to recipient dogs and assessing changes in pouch secretion (; see Lim Citation1927a; Lim, Loo, and Liu Citation1927).Footnote17 In fact, experimental animals united the varied research that the CPS cultivated. The Society was nominally dedicated to physiology but actually promoted the “physiological sciences” more broadly, which it defined as including physiology, biochemistry, and pharmacology.Footnote18 It emphasized an experimental approach to physiology: clinical physiology studies (for example, surveying body measurements of different ethnic groups) and training in human physiology (for example, surgical practice) had long been components of medical teaching and research in China, but the CPS was more interested in physiology experiments performed on animals.Footnote19 Pharmacologists studying chemical compounds and biochemists assessing nutrition extensively used animals as well, though they also conducted in vitro analyses. Given the Society’s broad scope, early on in planning Lim had even considered designating the Society an organization for experimental biology—there were simply “too few men” for one dedicated strictly to experimental physiology.Footnote22 While he ultimately highlighted his own discipline, the CPS brought together several fields. Experimental practice, especially on animals, unified them, more than did the subjects of their investigations.

Figure 2 Lim’s vivisection experiments. Left shows experimental setup for vivi-perfusion of a dog’s stomach (Lim, Necheles, and Ni Citation1927). Right shows transplantation setup to investigate stomach secretion in a dog (Hou and Lim Citation1929).

As the first and sole Chinese professional society dedicated to experimental biology in the Republican period, the CPS was central in a broader negotiation in the 1930s concerning the future direction of Chinese biology. This deliberation, in fact, revolved around the role of animals in research. Chinese biology had long emphasized descriptive taxonomy and morphology, dedicated to the collection and observation of local animals and plants. Taxonomists and morphologists justified their dominance by asserting that their disciplines were particularly suited to China. Collection required few resources and was therefore more appropriate to the financial situation of the country, devastated by decades of war. China had “vast land and abundant materials” (地大物博), plant taxonomist Ping Chih 秉志 declared, providing ready-made and yet undiscovered research subjects for taxonomists and morphologists to observe (Citation1933, 7). He also argued that the minimal training needed for collection was advantageous at a time when few people received formal scientific schooling. Though truly innovative taxonomic research would require expensive equipment, anybody could “behold wild flowers and plants, listen carefully to birdsong” (縱覽鄉野花草諦聽鳥歌), and thus practice biology (Citation1931, 108). In addition to these pragmatic considerations, descriptive biologists highlighted the tradition underpinning their vision of Chinese biology. Ping (Citation1931, 107) asserted that taxonomy was part of a longstanding Chinese practice of natural history. And plant taxonomist Hu Hsien-su 胡先驌 placed his discipline into a lineage dating back to ancient savants: “Confucius, with broad knowledge in the proclamations of names of birds, animals, and plants, can be considered the germination of taxonomy in our country” (孔子多識鳥獸草木之名之詔告,可謂為吾國分類學之萌芽) (Citation1932, 17).Footnote23 These biologists saw themselves as modern practitioners of time-honored customs. To them, collecting local animals and plants was both practical given material constraints and distinctively Chinese in its engagement with tradition and place.

However, experimental biologists conducting research on live animals were beginning to challenge their hold. In 1932, Johns Hopkins-trained psychologist Wang Ging-hsi 汪敬熙 decried what he saw as a narrow national focus on taxonomy and morphology and called for increased governmental funding for experimental research.Footnote24 While taxonomists sought to catalogue all species in China by researching dead organisms, experimentalists sought to answer the most exciting questions in contemporary biology—those concerned with life: how animals live, grow, and interact with their environment. These issues “needed to be researched on live animals with experimental methods” (須用實驗方法在活的生物身上去研究) (Citation1932, 10). Scientists had to investigate live, rather than inanimate, animals. In his indictment of the state of Chinese biology, Wang denigrated all but one research organization: the CPS was the only one doing first-rate, internationally recognized experimental biology (Citation1932, 9).Footnote25

Scientists like Wang were trying to convince their peers to develop experimental methods in China. In contrasting their live animals with descriptive biologists’ lifeless specimens, however, they were not only advocating a new approach to Chinese biology, but also revising the scientism by then entrenched in Republican Chinese culture. Since at least the Self-Strengthening movement in the late nineteenth century, elites had believed that science could modernize China and thus help address the country’s many political problems. But in 1931, Japan invaded Northeast China and established the puppet state of Manchukuo, which provoked a month-long battle between Japan and Shanghai residents protesting the invasion. By the 1930s, with the value of science already a given and with continued imperial encroachment, promotion of “science” in the abstract was no longer sufficient (see Shen Citation2016, 116–17). Advocating science was not enough for Wang and his colleagues. They thus attempted to shift the focus of Chinese biology from description to experiment by specifying the terms of scientism: experimental science in particular would help China catch up to imperial powers more quickly. In this framework, experiment was more advanced than description. Wang (Citation1936, 7) argued that scientific methodology developed from descriptive to experimental. And experimentalist P’eng Kuang-ch’in 彭光欽 (Citation1936, 17) claimed that science had further progressed to where the lines between the two were blurry; nevertheless, “traditional” (古典式) descriptive science solely based on observation was obsolete—the current era was the “era of experimental science” (試驗科學的時代).

They asserted that this era cut across geography. Wang (Citation1932, 9) contended that “world biology” (世界生物學) had since the late nineteenth century moved toward experimentation; further encouraging taxonomy and morphology would push Chinese biology in the “opposite direction” of the dominant current (趨勢相反) and be a sign of backwardness. For them, however, the West defined this “world” that China needed to enter: biologists took American and European science as the benchmark against which they compared Chinese science. One biologist even sought to refute Wang’s claim that experimentalism had overtaken world biology by calculating the proportion of articles in American and European journals that employed descriptive and experimental methods (C. Wang Citation1932, 12–13). Scientists abroad, he asserted, still practiced taxonomy and morphology. Western experimental scientists in fact continued natural historical practices of collection and description (Strasser Citation2019). But despite this reality, for these Chinese scientists, experimentalism had become linked to an idea of universal Western science that was then taking form (see Elshakry Citation2010). It signaled the modernity of powerful countries and thus stood in for a world Chinese elites aspired to enter. Experimentation therefore signified not simply a different scientific approach, but also an anti-imperial promise. Lim was known for his “‘super’ nationalistic spirit … a militant one” and “strong opinions with respect to the welfare and strengthening of his own country.”Footnote26 For experimentalists, the CPS he led would help China become an active participant in international science and therefore, perhaps, an equal in international politics too. Chinese experimental biologists thus proclaimed the need to adjust research priorities by drawing on and reworking a longstanding belief in the power of science to modernize China. Their new ways of practicing science came with new expressions of scientism.

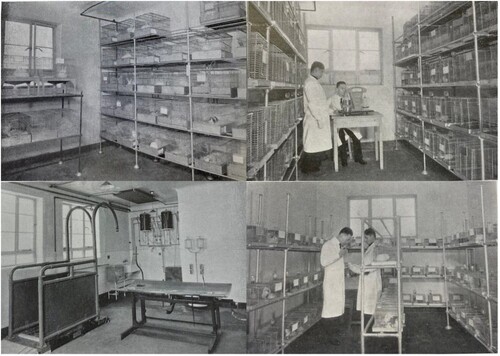

If experimental biology contained the promise of alleviating China’s political subordination, researchers would need a consistent supply of animals to get there. They devoted great effort to not only housing, but also breeding. At the PUMC, biologists established a stock colony of albino mice from 32 that were brought to the College in 1924 from the Rockefeller Institute in Princeton (Fortuyn Citation1931b). By 1934, the College had bred 2,190 albino mice in the first five months of the year and was building up colonies of rabbits and guinea pigs to meet demand.Footnote27 The Henry Lester Institute—a foreign-funded biomedical research institute in Shanghai established in 1932 and headed by CPS officers—also prioritized animal colonies. The Physiology Division spent the first months after the Institute’s founding breeding animals, especially Wistar rats; in 1939, colonies produced 750 rats and 999 mice.Footnote28 They were housed in a two-story, centrally heated animal house that also kept guinea pigs, dogs, sheep, goats, ponies, birds, cats, rabbits, and monkeys ().Footnote29 Scientists at research institutions across the country had to ensure reliable and sufficient access to animals. It was because of such need that the PUMC animal houses struggled to contain the multiplying number of animals. Hurried expansions were attempts to keep pace.

Figure 3 Lester Institute animal house. Clockwise from top left: “Rabbit room”; “Vitamin Research: Rats”; “Vitamin Research: Guinea pigs”; “Animal House: Operation Room.”Footnote30

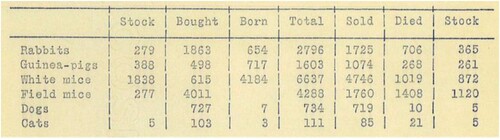

Lim and his CPS colleagues took advantage of the resources of their foreign-funded institutions to help other researchers across the country acquire the animals and other materials needed for experimental biology. As the requisite infrastructure was expensive and difficult to source, CPS scientists established networks of distribution.Footnote32 In 1934, the PUMC sold sixty to seventy percent of its rabbits, guinea pigs, and white mice, as well as almost all its dogs and cats ().Footnote33 Buyers may have used these animals for any number of reasons, but some of them presumably were other researchers who used them for experiments. The College also supplied physiological glassware. Around 1925, the PUMC had hired a German glassblower to make experimental instruments in-house instead of importing them.Footnote34 Lim worked with him to start a non-profit CPS initiative that designed and manufactured “complete sets of equipment suitable for conducting an experimental course” in order to “facilitate the development of experimental physiology.”Footnote35 Through this initiative, “workers in less well-equipped places” would have better research support.Footnote36 Indeed, it was part of a broader sharing of resources. Participating in a robust trading network spanning the country, scientists at the Lester Institute regularly shipped research and teaching materials to other institutions, including experimental animals, as well as also cages, slides, and sections.Footnote37 In a period when political instability and unequal treaties imposed by imperial powers severely limited public research funding, such distribution of animals and equipment helped make experimental biology possible in China and, thus, an articulation of a science—and scientism—of experiment.

Figure 4 PUMC animal accounting. Report to PUMC Animal House committee.Footnote31 Courtesy of Rockefeller Archive Center.

2 Through the Laboratory to the World

Researchers needed to be taught how to work with the animals being bred, delivered, and received in animal houses across the country. Lim recognized that making Chinese biology experimental required educational reform. At both the PUMC and nationwide, he encouraged training in experimental methods, especially for Chinese students, since “there [were] no Chinese seriously interested in physiology” when he first arrived.Footnote38 He offered practical courses at the College, such as one on “the physiology and experimental pathology of the alimentary tract … including a large amount of operative and experimental work” that likely would have been conducted on dogs, cats, and amphibians.Footnote39 And complaining that “the attitude ‘that Chinese students are not practical’ [was] harmful and due in part to the fact that the student is over-instructed,” he set promising students onto research questions in his laboratory, declaring that the work would help them “feel more confident in their own ability.”Footnote40 Lim (Citation1930) also pushed for greater prioritization of research in the medical sciences across China as president of the Chinese Medical Association 中華醫學會 (1930–32).Footnote41 For him, research served to stimulate the clinical work on which physicians focused. Few other Chinese institutions had resources even remotely comparable to the PUMC for research. But the growing use of experimental animals meant that people needed to learn how to work with them. Animal experimentation was implicated in medical and biological training more broadly.

Animals helped Chinese biologists participate in international science because they transformed research questions tied to locality into placeless knowledge that could circulate the world (see Kohler Citation2002). Through sacrifice, measurement, or other experimental manipulations, living, breathing animals turned into abstracted and mathematized data (; see Lynch Citation1988). For instance, experimentalists studying nutrition and pharmacology could use experimental animals to convert indigenous Chinese herbs and food into analytical numbers, formulas, and graphs. Lester Institute scientists investigated the vitamin C content of various Chinese fruits by feeding them to vitamin C-deficient guinea pigs. They measured the animals’ weight growth and made histological sections of their teeth to characterize signs of scurvy. Such probing of the animals’ bodies, as well as titration analyses of the fruits themselves, reduced the indigenous plants into abstract numbers describing the chemical compound “vitamin C” and graphs representing the compound’s effects on laboratory animals (see also Chi and Read Citation1935; Hou Citation1935).Footnote42 The results could ostensibly have been obtained anywhere and have implications for experiments conducted anywhere else (). Other researchers used animals to compare the pharmacological impacts of Chinese drugs on experimental animals to that of standard laboratory compounds found worldwide (e.g. Wang and Lu Citation1933). For Chinese experimentalists, animals were technologies of abstraction. They transformed place-based research into placeless knowledge that was legible to researchers abroad and part of international conversations.

Figure 5 Lester Institute experimental physiology laboratory. “Experimental physiology.”Footnote45

Figure 6 Animal abstraction. From left to right. Indigenous Chinese oranges, with American Sunkist orange for comparison; guinea pig used in vitamin C experiment; microphotographs of section of guinea pig incisor tooth and composite weight graphs (Hou Citation1935).

Because animals were so critical to the decontextualization of Chinese science, they themselves needed to be made as placeless as possible. Researchers standardized experimental animals.Footnote43 The PUMC bred animals under controlled conditions so that they would be “uniform and standard … free of disease, and of known age.”Footnote44 Breeding one’s own animals limited, or at least delineated, variables between them. And caring for animals from birth ensured they were healthy, particularly important in nutritional and pharmacological studies where the very health of the animal was the subject of investigation. For Chinese scientists, standardization made experimental animals into circumscribed laboratory materials that could be used to construct placeless and replicable knowledge; biologists elsewhere could perform similar experiments on their own animals. In contrast to the varied flora and fauna studied by descriptive biologists—inseparable from the specificity of their local environment—experimental animals were meant to be uniform and independent of their locality. Standardization was itself a process of abstraction from place.

And when experimentalists did use indigenous animals, they sought to detail each species’ particularities and minimize intra-animal variability so that information derived from the animals was as generalizable as possible. Researchers sometimes developed standardized animals from local organisms. At the PUMC, for instance, Dutch geneticist and anatomist A.B. Fortuyn established “a breed of pure albino rabbit of local origin.” With “characteristic long ears and slight body”—purportedly desirable characteristics in rabbits—this “local” rabbit also bred with two “foreign mixed breeds,” producing 654 offspring in 1933.Footnote46 Researchers also bred Mus wagneri, the central Asian analogue of the European house mouse Mus musculus, which had been domesticated and could be purchased in Peking markets by the 1920s (Fortuyn Citation1931b).Footnote47 In the 1930s, Fortuyn (e.g. Citation1931a, Citation1931b, Citation1931c, Citation1934) even began to genetically study the differences between the European and Asian mice, for example, the body weight and tailring number characteristic of each. Contrasting the genetically “impure stock” of laboratory animals being used with the “finest instruments and the purest chemicals … used for experimental work,” he argued it was probable that “in the laboratories of the world,” the two types of mice would be increasingly mixed and an account of potential differences was therefore critical (Citation1931b). That is, he predicted that animals would travel alongside experimental knowledge as the latter spread across the world. Scientists managed and controlled animals to facilitate such circulation.

Descriptive biologists shared this characterization of experimental knowledge as being less tied to place. Hu (Citation1932) countered Wang’s call to prioritize funding for experimental over descriptive biology by claiming that experimentalists could more easily bring back to China what they learned abroad. Biologists all generally studied in Japan, Europe, or the United States. But taxonomists deserved greater support, he insisted, because they had to adapt their foreign studies to the specific locality of China. With their experiments on standardized animals abstracting knowledge from place, experimentalists had an easier time conducting their work in China. Animals permitted experimentalists’ research to move across geography and appeal to scientists with shared interests who were conducting similar experiments elsewhere in the world. Placelessness allowed integration into international science. It thus also enabled experimentalists seeking greater research support to draw on a culture of scientism to assert that their internationally recognized work could more quickly bring China closer to equality with Western powers.

The CPS published a journal that aimed to circulate Chinese experimental biology internationally and bolster experimentalism in China. The Chinese Journal of Physiology 中國生理學雜誌 (CJP), started in 1927, reported mainly on nutritional investigations, pharmacological analyses, and physiology experiments, with occasional observational and clinical physiology studies.Footnote48 While many articles involved only in vitro work, a solid majority used experimental animals, whether they were fed, drugged, operated on, or provided sera (, ). Both in vitro and in vivo experiments abstracted from place to engage scientists in other countries. Indeed, Lim (Citation1927b) hoped that the CJP would “stimulate interest in scientific research in this backward country [China]” because it could serve as a forum for Chinese experimental biologists to reach international interlocutors in addition to each other. Articles were written in English (and occasionally French and German) with Chinese abstracts.Footnote49 Lim targeted seventy-five percent of subscriptions to be foreign and announced the journal’s establishment in Science and Nature (“Announcement” Citation1927a; “Announcement” Citation1927b).Footnote50 Papers also largely referenced American and European literature, and foreign scientists cited the CJP, though not extensively (). At least one or two articles a year were even published by researchers at foreign institutions (). While by no means a major international force, the journal put Chinese experimental biology in conversation with scientists abroad, facilitating experimentalists’ endeavors to actively participate in the making of international science and modernize Chinese biology. In 1936, P’eng wrote that it was often the only Chinese scientific journal he could readily find in libraries outside China (17). But as important as the international recognition the journal provided Chinese scientists was the opportunity it gave experimentalists to assert that their work was integrated into international science and thus advanced China’s international standing.

Figure 7 Animal experiments published in the CJP. Clockwise from top left: vivisection (Chang et al. Citation1937), pharmacology (Wang and Lu Citation1933), and nutrition experiments (Ni Citation1936).

Table 1 Number and percentage of articles in the CJP that use experimental animals. I include articles where animals were experimental subjects or provided material (e.g. muscles, sera) for experiments. The majority of articles not involving animals were nutritional and pharmacological studies that only used in vitro chemical methods. Asterisks indicate years when war conditions impacted the publication of the CJP, as noted by the journal. Research, including access to experimental animals, would presumably have been impacted as well. Japan captured Peking in 1941 and publication ceased after the third issue of the year.

Table 2 Number of articles that cite the CJP. The AJP and the JPL were the flagship US and UK physiology journals published by the respective national physiology societies, while the PSEBM published on experimental biology more generally. PR, like the AJP, was published by the American Physiological Society. The table begins in 1927, when the CJP begins publication, and ends in 1941, when the CJP ceased publication. Data drawn from the Web of Science.

Table 3 Institutional affiliations of authors publishing in the CJP. When sole authors have joint affiliations with the PUMC and/or a non-Chinese institute, or when a co-authored article includes authors affiliated with either category, I count the article toward “PUMC” and “Non-China,” respectively. Asterisks indicate years when war conditions impacted the publication of the CJP, as noted by the journal. These conditions may be responsible for the uptick of “% PUMC” beginning in 1938, as less resourced and less secure institutes were unable to continue normal research operations. Japan captured Peking in 1941 and publication ceased after the third issue of the year.

Animals and experiments allowed not only research to travel, but also scientists themselves to do so. Lim, through the CPS, worked to help Chinese experimental biologists connect with European and American scientists at international venues. He facilitated the hire of Chinese experimentalists at the PUMC—which provided support for travel and put them in contact with foreign scientists passing through Peking—and lobbied the College to fund non-PUMC Chinese scientists to present at the International Physiological Congresses.Footnote51 At the 1929 Congress in Boston, for instance, all eleven scientists from China presented experimental research, many of which involved Chinese food or drugs, as well as animal experiments (“Abstracts” Citation1929). Animals helped make their work legible to an international audience. And by participating in such making and dissemination of knowledge worldwide, Chinese experimentalists indicated to scientists both abroad and in China that their work was in keeping with “world biology.” They could contribute to the research of scientists in Western countries that were setting the terms of both international science and politics.

Research on live animals allowed CPS scientists to work from locality toward placelessness, that is, toward potential equality with, rather than subjugation to, imperial powers. They were forging a new scientism in advancing a science based in experiment. This process, however, was not seamless. Even as animals abstracted their work, the people performing the experiments were still constrained by the same power structures that made European and American scientists the arbitrators of the type of science to which Chinese biologists should aspire. Lim himself embodied such limits of abstraction. Born in Malaysia to a prominent Chinese family, he was raised in Edinburgh, trained in elite British and American institutions, and served in the British army during World War I. He had a Scottish lilt, and upon arrival at the PUMC joked to Sharpey-Schafer that his children spoke better Chinese than he and his Scottish wife did.Footnote52 Chinese scientists at the PUMC even doubted if he could be considered Chinese. Wu Hsien 吳憲, a biochemist who had grown up in China and obtained his undergraduate and doctoral degrees at MIT and Harvard before becoming the first Chinese chair at the PUMC, told College officials when Lim first arrived that “while Lim is originally by race a Chinese … he is foreign-born and reared and educated, so that from many practical aspects he is as unfamiliar to North China, or indeed to China as a whole, as a Westerner might be.”Footnote53 He appeared assimilated into international science.

Despite this appearance, Lim was less able to abstract from his Chineseness than the animals on which he experimented. Colleagues with whom he trained in the United States praised his talent, yet nevertheless noted that he impressed even “those who are prejudiced against the Chinese,” declaring him “the most brilliant Chinese physiologist so far produced … second to none of the best of the European or American physiologists.”Footnote54 Marked as such, he seems to have relocated to China—where he had never lived—because he had limited career prospects in the United States and Europe. In fact, at times his Chineseness made it difficult for him even simply to move through the world of science. Planning to present at a conference of British physiologists in Toronto en route to Peking, he was barred entry into Canada and forced to leave his train with his family at one thirty in the morning.Footnote55 The British Consul had to secure them a last-minute “private pass” to later enter the country.Footnote56 Administrators at the PUMC apologized for the oversight of its transportation department, repeating that it “never occurred to [them] as possible that a British subject could be refused entrance to Canada.”Footnote57 Only when the President of the Rockefeller Foundation wrote to the Prime Minister of Canada did they learn that the Chinese Immigration Act of 1923 barred “persons of Chinese origin or descent” from entering without special permission.Footnote58 Lim, a British subject attending an international scientific conference in a British dominion, was actively taking part in the making and dissemination of experimental knowledge. But he was also singled out by his ethnicity, from which he was unable to extract himself. Lim, the person, could not be placeless.

Within such constraints, however, Lim was able to accomplish much with the science he practiced and promoted: his efforts to advance experimental biology with the CPS appeared successful. Although PUMC researchers had supplied almost all early CJP articles, scientists from other institutions across the country gradually provided more papers (). While Lester Institute biologists authored a substantial proportion of non-PUMC articles after 1932, public institutions also had a strong presence. Already in 1929, for example, physiologists at Chungyang tahsüeh 中央大學 (Central National University) reported on the toxin resistance of 112 colectomized rats, while psychologists at Chungshan tahsüeh 中山大學 (Sun Yat-sen University) communicated a study on nerve reflexes in decerebrated cats (Su and Tsai Citation1929; Wang, Pan, and Lu Citation1929). Though the growth in non-PUMC papers may also have been due to the journal’s increased visibility, it nevertheless signaled a mainstreaming of animal experimentation in the 1930s. CPS scientists’ attempts to make Chinese biology experimental paid off. The international recognition they received also bolstered their contentions against descriptive biologists that their work was more in line with the international current and thus could better modernize China.

In 1942, Lim was unanimously elected as a foreign associate to the United States National Academy of Sciences. Members lauded “his services as a pioneer in the development of physiological science in China … his success in attracting very able young Chinese into scientific careers … and his outstanding ability in the application of modern medicine and surgery in China’s present need,” in addition to his work with the CPS and CJP.Footnote59 Experimental animals did not appear in the citation. However, this success would not have been possible without them.

3 Animal Scientism

As experimental animals moved from animal houses to laboratories to journal pages and conference presentations, they were not completely confined to the world of research. In 1926, local newspapers reported that the PUMC was buying dogs from suppliers who had taken them from the streets of Peking. Some had turned out to be local residents’ pets.Footnote60 Thus, as biologists went through thousands of animals a year, they began worrying about potential antivivisection activism. PUMC officials were anxious that the barking of experimental dogs was “very noticeable to people passing in the street.”Footnote61 One noted in 1926 that, while so far there had been no “strong anti-vivisectionist feeling,” a movement could arise at any moment and preventative measures were therefore “a matter of some importance.”Footnote62 Given the risk of community backlash, the new animal house constructed in 1934 was a low building, reducing the likelihood of barking sounds projecting over the College walls. PUMC scientists attempted to hide their animals from the outside environment even as the animals abstracted their work from it.

They had good reason to worry. As animal experimentation became more widespread in China, in 1933 a group of businessmen, educators, and local politicians in Shanghai established the Chinese Animal Protection Society (CAPS), the country’s first animal protection organization. The social elites who made up its leadership were particularly influential in Shanghai due to the political vacuum created by battles between warlords and the high density of foreign concessions.Footnote63 But despite the ostensible purpose of the CAPS, its ultimate mission was not animal protection per se, but world peace—especially peace for China. The Society’s work was undergirded by Buddhist principles.Footnote64 Most members were lay Buddhists, and it was based at the Shihchieh fochiao chüshihlin 世界佛教居士林 (World Buddhist Householder Grove), a Buddhist gathering space (“Chüshihlin” Citation1933). Members drew on Buddhist notions of “equality of life” (眾生平等) and the “shared essence of all things” (萬物為一) to contend that because all life was fundamentally the same, cultivating humans’ care for animals would also cultivate their care for other humans.Footnote65 Animal protection was a means to an end; it would encourage humans to be kinder to other living beings, helping them “prevail over cruelty and eliminate killing” (勝殘去殺) and eventually engender peace. To the protectionists, the resolution of world wars depended not on international treaties, but on “the kindness and evil of the human heart” (人心之慈暴) (“Nipan” Citation1933). Kindness would bring peace to China and an end to the violence that imperial powers inflicted on the country. In fact, scholars writing on the CAPS have argued that Chinese animal protectionists saw victimized animals as a metaphor for China, oppressed by the powerful (Lai Citation2010; Poon Citation2015). CAPS members’ plea for equality between animals and humans was also a call for equality between China and the rest of the world.

But even though experimentalists worried about antivivisectionism, the CAPS never protested animal experimentation. The Society knew of their research. Many CAPS founding members were educators who would likely have kept abreast of developments in scientific and medical education. Notably, one of them was Harvard-trained surgeon and anatomist New Way-sung 牛惠生, who succeeded Lim as President of the Chinese Medical Association and oversaw nation-wide attempts to reform the medical curriculum.Footnote66 Educated abroad, he likely had even vivisected animals himself and was almost certainly friendly with CPS members. And members knew not only that biologists were experimenting on animals, but also that antivivisection was an important animal protection issue. The CAPS was significantly influenced by animal protection movements in Europe and the United States, and members recognized their strong tradition of antivivisection activism.Footnote67 Poet and widely published journalist Lü Pich’eng 呂碧城—an important early figure in Chinese animal protection whom CAPS members cited—wrote about the New England Anti-Vivisection Society and published many antivivisection articles in China (Lai Citation2010, 101–2).Footnote68 In 1931, she publicly condemned a physician whom the press had praised for experiments he conducted on dogs while studying in Japan, branding vivisection as “ten thousand evils” (萬惡) and “an insult to humanity” (污辱文明) (Citation1931). Medical and Buddhist periodicals also occasionally translated English-language antivivisection pamphlets with supportive commentary (see, e.g. Shihchieh hsinwenshe Citation1930; Ching Citation1930). Thus, with the growing prevalence of animal experimentation, shared social networks between the CPS and CAPS, and the proximity of the Lester Institute and the CAPS in Shanghai, there was real potential for antivivisection activism.

Animal protectionists’ recognition that science had an important role to play in their goal to end cruelty to living beings and to China likely factored into their choice to not protest animal experimentation. Like other elites in the period, they grappled with an established scientism. With religion dismissed as superstitious, the Buddhist community with which CAPS was associated aligned Buddhism with science while insisting that Buddhist principles could infuse materialistic science with much-needed ethics (Nedostup Citation2009; Hammerstrom Citation2015, especially chap. 5). More broadly, the need to maintain good relations with the secular Republican government pushed Buddhists to combine aspects of religious and secular authority in their advocacy (Jessup Citation2016). Indeed, though motivated by Buddhist principles, the CAPS presented itself as secular and actively recruited non-Buddhists; one of its founding members was a prominent Catholic businessman (“Nipan” Citation1933; Hui Citation1934).Footnote69 And members themselves expressed scientism in their activism. In 1934, when the Shanghai Public Health Bureau culled over twenty horses infected with gangrene, CAPS members denounced the action, emphasizing that horses and humans shared an essence and differed only in form; if human disease could be treated, so could that of animals. But they also insisted that the horses were shot because Chinese science—in general, and not limited to veterinary science—was too “immature” (幼稚), a “laughing stock of foreign countries” (貽笑外邦) unable to save the animals from death (“Paohu” Citation1934). Their lament about the state of Chinese science echoed that of experimentalists who argued that descriptive biology was of the past and that research on live animals would push biology to be on par with that practiced in foreign countries. Chinese science needed to advance.

As experimentalists sought support for their work, they had put forth a scientism of experiment based on animals. For them, as for the protectionists, advocating “science” was already a given. The state of Chinese science had to further improve, and experimentation offered a path forward. Thus, while it has been argued that CAPS members did not take up antivivisection because it was not a traditional Buddhist concern, an entrenched culture of scientism—one that experimentalists were then reworking—was also likely an important factor (see Poon Citation2019). Protectionists recognized the implications of scientific development for both animals and China and perhaps decided that integrating antivivisection into its advocacy did not further its mission for peace. In fact, the CAPS drew on many aspects of Western animal protection that had no ostensible Buddhist connections. Members packaged Buddhist notions of vegetarianism, releasing captive animals, and prohibition of killing animals into Western-style publicity campaigns, such as essay competitions for children (Poon Citation2015). The Society also imported “World Animal Day,” which celebrated the patron saint of animals, Saint Francis of Assisi, and made the commemoration central to its promotion of the Buddhist doctrine of “non-killing” (Poon Citation2019, 99–103). This Catholic event was not a traditional Buddhist activity. Yet the CAPS appropriated it to advance the Buddhist-based belief in the sanctity of life—which they also could have done with antivivisection. The absence of antivivisection in traditional Buddhism was no doubt important, and the shared networks among scientists and protectionists in elite social circles may have pushed the CAPS to refrain from protesting animal experimentation. But even if not protesting animal experimentation was passive rather than active, with the practice being so important to the American and European movements from which CAPS drew significant inspiration, it was a choice. Members knew that scientific advancement could aid not only animal protection but also China’s international standing—and experimental animals were central to that aspiration. Experimental animals, in short, may have been seen as justifiable sacrifices to the science that would free China from imperial control.

Animals had therefore acquired a cultural valence as they moved from the animal house to the laboratory and circulated the world. Non-scientists knew that animals were being used to make scientific knowledge. As experimentalists practiced and demonstrated their participation in “world biology,” animals simultaneously embodied the material and symbolic dimensions of a scientism of experiment. They signified a future where China would be an international equal to more powerful nations. Manifestation of a widespread anti-imperialist desire to save China through science, they brought experimental biologists and animal protectionists together as allies instead of as enemies. Ironically, it was China’s specific political and scientific situation in relation to the West that led placeless animals to provoke this place-based alliance. Here, rather than be protected, animals could—through science—help protect China.

4 Conclusion

In 1947, a civil war between the Nationalists and Communists continued raging after the end of the Sino-Japanese War. As the PUMC lay shuttered, a report from the College’s animal house arrived at the Rockefeller Foundation. Throughout the conflicts of the past decade, the animal house supervisor had continued to breed and house small animals, perhaps for war-related medical research or vaccine production.Footnote70 Unfortunately, he “[did not] have a very flourishing business.”Footnote71 There were 3,500 mice, 200 rabbits, 120 guinea pigs, and 200 rats. The PUMC, the report said, would be given a specified proportion of the animals when the time came to reopen. Even as research halted and conflict engulfed the country, experimental animals continued to be bred and distributed, and the animal house continued to stand.

Amid the horrors of war, animals thrived in their dedicated facilities. Insulated from locality due to their scientific value, they inverted who, and what needed protection. Instead of the animals being used for experiments, it was those they had stood in for: humans—and China—suffering at the hands of the powerful. At the PUMC, animals continued to embody hopes for a scientific future. When the war ended, when peace came to China, and when biologists returned to their laboratories, animals would be waiting, ready for scientists to continue their experiments.

From the animal house through the laboratory to journal articles and international conference presentations, and even to the cultural discourse of elites, animals held the promise of a better future for China. Biologists used them to move away from taxonomic and morphological investigations of local flora and fauna toward laboratory research of life that was unspecific to place. Animal protectionists saw in them the potential to foster human kindness toward all beings. The aspirations of both were inflected by anti-imperialist desires. Biologists adhering to a progressive understanding of scientific methodology tried to make Chinese biology experimental by reworking the scientism ingrained among elites: compared to science in general, and especially descriptive science, experimental science could help China more quickly catch up to Western powers. By being part of “world biology,” defined largely by American and European scientists, Chinese experimental biologists asserted that they too were active participants in international science and thus that experimentation could help China become an equal. Pacifist and anti-imperialist protectionists shared such ambitions. They recognized that science could not be separated from their ultimate aim of peace for the country. As biologists specified the importance of experimentation, protectionists recognized the significance of the revised scientism. Animals, a critical material component for experimental science, embodied a scientism that could help free China from imperial subjugation.

The aspiration for Chinese experimental biology—and the work done to realize it—is one that historians of science would do well to take seriously. To appreciate the complicated motivations behind making Chinese biology experimental is to challenge the implicit historiographical association of descriptive biology with China and experimental biology with the West. It is also to recognize that scientists did not simply transplant experimental biology into China; the CPS fostered Chinese talent, built the discipline up using local resources and networks, and remained concerned with research questions pertinent to China. They worked toward placelessness through place-based means. These developments had cultural implications beyond the realm of scientists. Tracing animal protectionists’ response, or lack thereof, to animal experimentation not only reveals the Chinese specificity of animals’ role in experimental biology but also puts China in conversation with the rich extant literature on physiology and vivisection in Europe and the United States. Animals, as Chinese experimental biologists well knew, were—and remain—crucial resources mediating between place and placelessness, the past and the present.

Acknowledgments

For their help in the preparation of this article, many thanks to He Bian, Lijing Jiang, Sofia Menemenlis, Jacob Neis, Amelia Urry, Michelle Wen, Albert Wu, and participants of the Spring 2022 Princeton History of Science Program Seminar, especially Jingwen Li and Keith Wailoo. Thanks also to the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments. Previous versions of this paper were given at meetings of the History of Science Society, the Joint Atlantic Seminar for the History of Biology, and the American Historical Association; thanks to Brad Bolman for invitations and co-organization. I am also grateful to the staff at the Rockefeller Archive Center, especially Bethany Antos. Thanks in particular to Mary Brazelton and Angela Creager for invaluable guidance. The British Society for the History of Science provided generous research funding.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Anin Luo

Anin Luo is a doctoral candidate in the Program in History of Science at Princeton University. She is an intellectual historian interested in philosophical and scientific understandings of life, health, and the environment. Her dissertation is a postwar international history of immunity.

Notes

1 On the PUMC, see Bullock Citation1982.

2 Roger S. Greene to Margery K. Eggleston, “Housing of Animals: Attention Dr. Houghton,” April 16, 1926, Folder 79, Box 12, Record Group 1, China Medical Board records, Rockefeller Archive Center (China Medical Board material hereafter cited in the format RAC/CMB/[Record Group]/[Series, if applicable]/[Box]/[Folder]). Due to the amount of archival material on which this essay draws, archival material will be cited in footnotes rather than in text.

3 “Mongolian Camel,” 1920–1921, RAC/CMB/1/1048/30/331.

4 A notable exception is Xu Citation2021, which provides an empirically rich account of the life science research, including experimental biology, conducted at Tsinghua University 清華大學. Jia-Chen Fu (Citation2016) has analyzed experimental work at the Henry Lester Institute—which I discuss in this essay—but does not trace the history of experimental biology itself. On descriptive biology in Republican China, see, e.g., Haas Citation1988; Jiang Citation2016; Luk Citation2021.

5 See Fan Citation2014 for opposing visions of modern science—around the specific case of spontaneous generation—in the early 1930s. While Fan illustrates conflicting visions of modern science by focusing on differences in experimental interpretation, this essay shows how experiment itself was contested in debates on the relationship between science and nation.

6 These scientists were drawing on a distinction between experiment and description that historians of biology have long nuanced, though the scholarship has focused almost exclusively on the United States. For the classic account of twentieth-century experimental biology being a “revolt” from nineteenth-century descriptive morphology, see Allen Citation1975. For critiques, see Maienschein, Rainger, and Benson Citation1981; and more recently, Strasser Citation2019.

7 On the animal as a scientific object, see Lynch Citation1988. For the classic treatment on quantification’s bridging of distance, see Porter (Citation1995) 2020. The historiography on experimental animals and model organisms is extensive; see essays in Journal of the History of Biology special issue edited by Brad Bolman, especially Creager Citation2022.

8 All translations mine. In the body text, I use Wade-Giles romanization, standard to the period under study, unless pinyin is conventional for a proper noun. For citations, I use Wade-Giles romanization for all sources published pre-1949 or in Taiwan and pinyin romanization for all sources published in the People’s Republic of China post-1949. I provide translations of periodical titles if there is a set or common one for the periodical.

9 While this essay is the first history of the relationship between vivisectionists and animal protectionists in China, that relationship has long fascinated historians of science and medicine in Europe and the United States. Scholars have emphasized the adversarial relationship between the two, often focusing on questions of class or gender. In the context of Chinese scientism, there was no such antagonism. See, e.g., Kremer Citation2009, especially 356–58; French Citation1975; Geison Citation1978; Lansbury Citation1985; Lederer Citation1992; Rupke Citation1987.

10 On the universal as internal to the local in the making of modernity in Asia, see Chen Citation2010, 222–23. On science in this framework of “Asia as method,” see Fan Citation2016; and in the specific context of scientism, Fan Citation2022.

11 “WSC: Interview with Dr. RKS Lim,” August 31, 1925, RAC/CMB/1/122/886; W.S. Carter to Roger S. Greene, April 14, 1926, RAC/CMB/1/12/79.

12 Roger S. Greene to Margery K. Eggleston, “Housing of Animals: Attention Dr. Houghton,” April 16, 1926, RAC/CMB/1/12/79. Number of dogs from “Conference with Dr Ten Broeck (& Dr Yü), Dr B E Read, Dr Robert Lim, Mr Hogg, Dr J H Liu, Dr Grant. Subject: Supply of Dogs,” May 28, 1926, RAC/CMB/1/12/79.

13 It is unclear whether the expedited authorization was approved, but the animal house was. See Greene to Eggleston, “Housing of Animals: Attention Dr. Houghton,” April 16, 1926, and Greene to Eggleston, “Animal Houses,” June 22, 1926, RAC/CMB/1/12/79.

14 “Report of the Committee on the Animal House,” June 1, 1934, RAC/CMB/1/12/79.

20 “Building N – Animal House, 1919, 1927, 1934,” March 21, 1934, RAC/CMB/1/Drawer C14/77.

21 “Building D – Animal House, 1935,” December 1934, RAC/CMB/1/Drawer C12/72

15 Sharpey-Schafer was an important second-generation member of Michael Foster’s Cambridge School of Physiology (see Geison Citation1978), and Carlson was the most productive physiologist in the United States in the early twentieth century (Geison Citation1987).

16 For a list of Lim’s publications and a biography focusing on his scientific accomplishments, see Davenport Citation1980. See also Liu and Guo Citation2012.

17 It is unclear what Lim thought of these experimental animals, though he named his laboratory dogs (e.g., “Brownie,” January 11, 1949, 064-01-07-01, Lim Kho-seng Papers, Institute of Modern History Archives, Academia Sinica [hereafter LKSP]).

18 “The Chinese Physiological Society Constitution and List of Members,” 1933, 064-01-43-001, LKSP. For the remainder of this essay, I use “physiological sciences” to refer collectively to physiology, biochemistry, and pharmacology in the context of the work of the CPS. “Experimental biology” denotes these same fields, but I use it to refer to a vision of biology that contrasts with descriptive biology. “Experimental physiology” specifically indicates an experimental approach to physiology. While “physiology” here brought together different disciplines under “physiological sciences,” in the early twentieth-century United States it had an uneasy relationship with medicine, biology, and various subfields of each—terminology was thus a general issue not specific to China. For the American case, see Pauly Citation1987; Maienschein Citation1987.

19 For an example of the anatomy and physiology components of medical examination, see “Chinese M.Ds” Citation1919; Luesink Citation2017. For a discussion of clinical physiology research and education, see “Sectional Meetings” Citation1923; Earle Citation1923.

22 Robert K.S. Lim to Edward Sharpey-Schafer, October 30, 1925, PP/ESS/F.4, Edward Sharpey-Schafer Papers, Wellcome Library (hereafter ESP).

23 On the dominance of plant taxonomy, see Haas Citation1988.

24 On Wang’s exchange with Hu, focusing on the two figures in the context of the New Culture Movement, see Li Citation2009. Romanization of Wang’s name is drawn from his published scientific articles: the Wade-Giles romanization is Wang Ching-hsi. See for an example of his research.

25 According to Schneider (Citation2003), however, by the 1920s a number of geneticists had already begun conducting experimental research in China.

26 Correspondence between Henry S. Houghton and Arno B. Luckhardt, November 18 and 20, 1936, RAC/CMB/1/123/890. In the historiography of Chinese science and medicine, Lim is best known for his nationalist medical work, especially for establishing the Chinese Red Cross Medical Relief Corps during the Sino-Japanese War. It served as the wartime health ministry (Soon Citation2020, 52–53, chap. 2).

27 “Report of the Committee on the Animal House,” June 1, 1934, RAC/CMB/1/12/79.

28 “Henry Lester Institute of Medical Research,” 43, 1933, East Asian History of Science Library, Needham Research Institute, University of Cambridge (hereafter NRI); Henry Lester Institute of Medical Research 1939 Annual Report, 13, NRI. The Wistar Institute had already been advertising its rats in Chinese medical journals in 1919; see “The Wistar Institute of Anatomy and Biology” Citation1919.

29 “Henry Lester Institute of Medical Research,” 18–24, 1933, NRI. On the Institute and its animal house see Fu Citation2016.

30 “Henry Lester Institute of Medical Research,” 1933, NRI.

32 On material infrastructure in American physiology, see Borell Citation1987.

33 “Report of the Committee on the Animal House,” June 1, 1934, RAC/CMB/1/12/79.

34 H. Barchet to Roger S. Greene, “Glassblower,” January 12, 1925, RAC/CMB/1/122/886.

35 Robert K.S. Lim and C.H. Wang, draft of “The Physiological Sciences in China,” 11, December 27, 1960, 064-01-22-052, LKSP.

36 Robert S. Greene to Henry S. Houghton, “Interview with Dr. R. Lim,” September 7, 1926, RAC/CMB/1/122/886.

37 For example, twelve white mice and a mouse cage were sent to Hong Kong University in 1935 (Henry Lester Institute of Medical Research 1935 Annual Report, 81, NRI).

31 “Report of the Committee on the Animal House,” June 1, 1934, RAC/CMB/1/12/79.

38 Henry S. Houghton to Margery K. Eggleston, “Department of Physiology: Dr RKS Lim: Dr Cruickshank,” April 23, 1925, RAC/CMB/1/122/886. Lim’s efforts were part of a broader movement. Scientists who had sought graduate training abroad in the 1910s and 20s—many on the Boxer Indemnity Fund—were returning and reforming Chinese academia; see Wang Citation2002; Soon Citation2020.

39 Robert K.S. Lim to Roger S. Greene, July 12, 1924, RAC/CMB/1/123/890. This course was one that Lim proposed to the PUMC. I have not been able to confirm for certain that he taught this specific course, but he did teach one that involved experimental thyroidectomy in amphibians and mammals (“HSH: Invited by Dr Robert KS Lim to attend the Final Physiology Seminar, D-Building, 4 pm,” June 1, 1927, RAC/CMB/1/122/886).

40 Robert K.S. Lim to Roger S. Greene, November 6, 1924, RAC/CMB/1/123/890.

41 On medical education reform, see Yan Citation2019.

42 For nutritional scientific research in this period, see Fu Citation2018.

45 “Henry Lester Institute of Medical Research,” 1933, NRI.

43 On the standardization of the laboratory mouse, see Rader Citation2004; and of the Wistar rat, see Clause Citation1993.

44 “Report of the Committee on the Animal House,” June 1, 1934, RAC/CMB/1/12/79.

46 “Report of the Committee on the Animal House,” June 1, 1934, RAC/CMB/1/12/79.

47 The two types of mice are now considered the same species, Mus musculus.

48 For positive reviews of the CJP in China, see “The Chinese Journal of Physiology” Citation1927; W.L.T. Citation1927.

49 In the early 1930s, this requirement was loosened so that Chinese articles could be published if accompanied by a translation in any of the three European languages; less than ten articles before 1941 were in Chinese. On the politics of language and international science in Republican China, see Shen Citation2014.

50 Robert K.S. Lim to Edward Sharpey-Schafer, October 30, 1925, PP/ESS/F.4, ESP.

51 On Lim hiring Chinese staff, see “WSC Interviews: Dr. Robert K.S. Lim,” December 8, 1925, RAC/CMB/1/122/886; Soon Citation2020, 49–50. On sending Chinese scientists to international conferences, see “Memorandum: Dr. Robert Lim (returned from Shanghai),” July 18, 1928, RAC/CMB/1/123/890. Though Lim attempted to secure funding for non-PUMC Chinese scientists from Shanghai and Canton to attend the 1929 International Physiology Congress, it seems that only PUMC scientists went; nine of the eleven were Chinese.

52 Robert K.S. Lim to Edward Sharpey-Schafer, October 30, 1925, PP/ESS/F.4, ESP. Scottish accent from Davenport Citation1980, 281.

53 “Memorandum: Conversation with Dr Wu Hsien,” November 27, 1924, RAC/CMB/1/123/890.

54 Anton J. Carlson to Roger S. Greene, February 4, 1924, RAC/CMB/1/123/890; Carlson to Greene, February 25, 1925, RAC/CMB/1/122/886.

55 Margery K. Eggleston to Deputy Minister of Immigration and Colonization, August 4, 1924; Robert K.S. Lim to Roger S. Greene, August 4, 1924, RAC/CMB/1/123/890.

56 Robert K.S. Lim to Roger S. Greene, August 4, 1924, RAC/CMB/1/123/890.

57 Margery K. Eggleston to Robert K.S. Lim, August 7, 1924, RAC/CMB/1/123/890.

58 George E. Vincent to W.L. Mackenzie King, August 15, 1924; “Memorandum: Mr. F.A. McGregor,” August 20, 1924; King to Vincent, August 22, 1924, RAC/CMB/1/123/890.

59 W.B. Cannon to E.C. Lobenstine, April 29, 1942, RAC/CMB/1/123/891.

60 “Conference with Dr Ten Broeck (& Dr Yü), Dr B E Read, Dr Robert Lim, Mr Hogg, Dr J H Liu, Dr Grant. Subject: Supply of Dogs,” May 28, 1926, RAC/CMB/1/12/79.

61 Roger S. Greene to Margery K. Eggleston, “Housing of Animals: Attention Dr. Houghton,” April 16, 1926, RAC/CMB/1/12/79.

62 Roger S. Greene to Margery K. Eggleston, “Housing of Animals: Attention Dr. Houghton,” April 16, 1926, RAC/CMB/1/12/79.

63 On the significant influence of social elites in Republican Shanghai, see Shen Citation2007.

64 For a contemporary argument for animal ethics based on Buddhist principles, see Shih Citation2019.

65 On the Buddhist influences of the CAPS, see Poon Citation2015.

66 Founding members drawn from signatories of “Chüshihlin” Citation1933. On New, see Boorman, Cheng, and Krompart Citation1967, 43–44. On New and medical education reform, see Yan Citation2019.

67 On the influence of Western animal protection movements, see “Chüshihlin” Citation1933.

68 For Lü’s influence on the CAPS, see “Nipan” Citation1933. On Lü’s animal protection more generally, see Fan Citation2010; Liu Citation2019.

69 The Catholic businessman, whose philanthropic activities lay in the medical field, was Lu Po-hung 陸伯鴻.

70 On the importance of living organisms in the production of vaccines during the war, see Brazelton Citation2019, chap. 1.

71 “Excerpt MEF Diary,” January 24, 1947, RAC/CMB/1/12/79.

References

- “Abstracts of Communications to the Thirteenth International Physiology Congress”. 1929. American Journal of Physiology 90 (2): 258–571.

- Allen, Garland E. 1975. Life Science in the Twentieth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- “Announcement”. 1927a. Science 65 (1681): 278.

- “Announcement”. 1927b. Nature 119: 826.

- Boorman, Howard L., Joseph K. H. Cheng, and Janet Krompart. 1967. Biographical Dictionary of Republican China. Vol. 3. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Borell, Merriley. 1987. “Instruments and an Independent Physiology: The Harvard Physiological Laboratory, 1871–1906.” In Physiology in the American Context 1850–1940, edited by Gerald L. Geison, 293–321. New York, NY: Springer.

- Brazelton, Mary Augusta. 2019. Mass Vaccination: Citizens’ Bodies and State Power in Modern China. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Bullock, Mary Brown. 1982. An American Transplant: The Rockefeller Foundation and Peking Union Medical College. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Chang, Hsi-Chun, Kuo-Fan Chia, Ching-Hsiang Hsu, and R. K. S. Lim. 1937. “Humoral Transmission of Nerve Impulses at Central Synapses. I. Sinus and Vagus Afferent Nerves.” Chinese Journal of Physiology 12 (1): 1–36.

- Chen, Kuan-Hsing. 2010. Asia as Method: Toward Deimperialization. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Chi, Youh-Fong, and Bernard E. Read. 1935. “The Vitamin C Content of Chinese Foods and Drugs.” Chinese Journal of Physiology 9 (1): 47–62.

- “Chinese M.Ds.: Examinations in Anatomy and Physiology”. 1919. The North-China Daily News, January 23.

- Ching Ch’eng 鏡澄. 1930. “Huo p’ou” 活剖 (“Vivisection”). Tzuch’iang ihsüeh yüehk’an 自強醫學月刊.

- “Chüshihlin nei hsinshe chih Chungkuo Paohu Tungwu Hui” 居士林內新設之中國保護動物會 (“Chinese Animal Protection Society Newly Established in Householder’s Grove”). 1933. Weiyin 威音.

- Clause, Bonnie Tocher. 1993. “The Wistar Rat as a Right Choice: Establishing Mammalian Standards and the Ideal of a Standardized Mammal.” Journal of the History of Biology 26 (2): 329–349. doi:10.1007/BF01061973

- Creager, Angela N. H. 2022. “Model Organisms Unbound.” Journal of the History of Biology 55 (1): 21–28. doi:10.1007/s10739-022-09675-8

- Davenport, Horace W. 1980. “Robert Kho-Seng Lim.” In Biographical Memoirs, 51, 281–306. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press.

- Earle, Herbert E. 1923. “Clinical Physiology.” Chinese Medical Journal 37 (12): 1010–1013.

- Elshakry, Marwa. 2010. “When Science Became Western: Historiographical Reflections.” Isis 101 (1): 98–109. doi:10.1086/652691

- Fan, Chun-wu 范纯武. 2010. “Qingmo Minchu nüciren Lü Bicheng yu guoji shushi yundong” 清末民初女词人吕碧城与国际蔬食运动 (“Late Qing Early Republic Female Poet Lü Bicheng and the International Vegetarian Movement”). Qingshi yanjiu 清史研究 (The Qing History Journal) 2: 105–113.

- Fan, Fa-ti. 2014. “The Controversy over Spontaneous Generation in Republican China: Science, Authority, and the Public.” In Science and Technology in Modern China, 1880s-1940s, edited by Jing Tsu, and Benjamin A. Elman, 209–244. Leiden: Brill.

- Fan, Fa-ti. 2016. “Modernity, Region, and Technoscience: One Small Cheer for Asia as Method.” Cultural Sociology 10 (3): 352–368. doi:10.1177/1749975516639084

- Fan, Fa-ti. 2022. ““Mr. Science”, May Fourth, and the Global History of Science.” East Asian Science, Technology and Society: An International Journal 16 (3): 279–304. doi:10.1080/18752160.2022.2095099

- Fortuyn, A. B. Droogleever. 1931a. “Mus Musculus and Mus Wagneri Compared. II. the Body Weight.” Genetics 16 (2): 168–174. doi:10.1093/genetics/16.2.168

- Fortuyn, A. B. Droogleever. 1931b. “Mus Musculus and Mus Wagneri Compared. I. The Number of Tailrings.” Genetics 16 (2): 160–167. doi:10.1093/genetics/16.2.160

- Fortuyn, A. B. Droogleever. 1931c. “A Cross between Mice with Different Numbers of Tailrings.” Genetics 16 (6): 591–594. doi:10.1093/genetics/16.6.591

- Fortuyn, A. B. Droogleever. 1934. “A Remarkable Cross in Mus Musculus.” Genetica 16: 3–4.

- French, Richard D. 1975. Antivivisection and Medical Science in Victorian Society. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Fu, Jia-Chen. 2016. “Houses of Experiment: Making Space for Science in Republican China.” East Asian Science, Technology and Society: An International Journal 10 (3): 269–290.

- Fu, Jia-Chen. 2018. The Other Milk: Reinventing Soy in Republican China. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

- Geison, Gerald L. 1978. Michael Foster and the Cambridge School of Physiology: The Scientific Enterprise in Late Victorian Society. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Geison, Gerald L. 1987. “International Relations and Domestic Elites in American Physiology, 1900–1940.” In Physiology in the American Context 1850–1940, edited by Gerald L. Geison, 115–154. New York: Springer.

- Haas, William J. 1988. “Botany in Republican China: The Leading Role of Taxonomy.” In Science and Medicine in Twentieth-Century China: Research and Education, edited by John Z. Bowers, J. William Hess, and Nathan Sivin, 31–64. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Hammerstrom, Erik J. 2015. The Science of Chinese Buddhism: Early Twentieth-Century Engagements. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Hou, Hsiang-Chuan. 1935. “A Comparative Study of the Vitamin C Content of Several Varieties of Chinese Oranges.” Chinese Journal of Physiology 9 (3): 223–244.

- Hou, Hsiang-Chuan, and Robert K. S. Lim. 1929. “The Basal Secretion of the Stomach. II. The Influence of Nerves and the Question of Secretory ‘Tone’ and Reactivity.” Chinese Journal of Physiology 3 (1): 41–56.

- Hu, Hsien-su 胡先驌. 1932. “Yü Wang Ching-hsi hsiensheng lun Chungkuo chinjih chih shengwu hsüehchieh” 與汪敬熙先生論中國今日之生物學界 (“Discussing the State of Biology in China Today with Wang Ging-hsi”). Tuli p’inglun 獨立評論.

- Hui, Yüan 會圓. 1934. “Chungkuo Paohu Tungwu Hui chih tiwei fenhsien” 中國保護動物會之地位分限 (“Limit of Hierarchy of the Chinese Animal Protection Society”). Hushengpao chiche 護生報記者.

- Jessup, J. Brooks. 2016. “Buddhist Activism, Urban Space, and Ambivalent Modernity in 1920s Shanghai.” In Recovering Buddhism in Modern China, edited by Jan Kiely, and J. Brooks Jessup, 37–78. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Jiang, Lijing. 2016. “Retouching the Past with Living Things: Indigenous Species, Tradition, and Biological Research in Republican China, 1918–1937.” Historical Studies in the Natural Sciences 46 (2): 154–206. doi:10.1525/hsns.2016.46.2.154

- Kohler, Robert E. 2002. “Place and Practice in Field Biology.” History of Science 40 (2): 189–210. doi:10.1177/007327530204000204

- Kremer, Richard L. 2009. “Physiology.” In The Cambridge History of Science, edited by Peter J. Bowler, and John V. Pickstone, 342–366. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kwok, D. W. Y. 1965. Scientism in Chinese Thought 1900–1950. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Lai, Shu-ch’ing 賴淑卿. 2010. “Lü Pich’eng tui hsifang paohu tungwu yüntung te ch’uan chieh—i Oumei chih Kuang wei chunghsin te t’ant’ao” 呂碧城對西方保護動物運動的傳介—以《歐美之光》為中心的探討 (“Lü Pich’eng’s Mediation of the Western Animal Protection Movement: An Investigation Centered on The Light of Europe and the United States”). Kuoshikuan kuan k’an 國史館館刊 (Academia Historica) 23: 79–118.