Abstract

Acquired brain injury (ABI) represents a great burden for not only the person with ABI but also their partner. Grief among partners of adults with ABI is a broadly recognized phenomenon. However, few studies have examined partners’ experience of grief, and little is known about grief as a reaction to ambiguous loss. This article presents a phenomenological study that aimed to explore the experience of grief among caregiving partners. Four semi-structured interviews were conducted and analyzed by a phenomenological descriptive analysis. Through the analysis, nine themes were identified: the process of becoming a caregiver, grief emotions, loss, emotionally closer relations to the partner relations, dyadic coping, unmet needs for support, future opportunities, changes over the life course, and understanding of grief. The themes are interrelated and highlight various aspects of the phenomenon of grief as experienced by caregivers. Results reveal that grief is often a reaction to ambiguous loss and is experienced as disenfranchised. Furthermore, the study indicates that caregivers’ perception of grief and the situation in general were essential to the experience of grief.

Introduction

Every year, an acquired brain injury (ABI) disrupts life for approximately 140,000 adults and their relatives in the Nordic Countries (Danish Board of Health, Citation2011; Norsk Hjerneslagregister, Citation2018; Hjärnfonden.se; Eilertsen, Kirkevold & Bjørk, Citation2010). When a person acquires a brain injury it not only affects the person’s life, but the life of the family and friends as well.

An ABI can lead to a range of different long-term physical, emotional, behavioral, and social consequences for the individual with ABI, but also experienced by the family. It is not only the direct ABI impairments and consequences that affects the healthy partner, also changes in roles (from partner to caregiver) and the general change in everyday life (Braine, Citation2011). Therefore, an ABI can be characterized as a life changing event that cause transitions in the entire family. A transition in the family can be defined as: “[…] events that require changes of roles, behaviours, expectations, and interactions among members” (Murray & Broadus, Citation2011, p. 502f). Both the ABI survivor and the caregiver often experience crisis and grief reactions as a part of this life-changing event (Jeffreys, Citation2011).

The understanding of grief has changed over time and different understandings of grief are to be found in the literature even today (Worden, Citation2002; Jeffreys, Citation2011; Guldin, Citation2014). Central to all understandings of grief is loss as the decisive factor. In the literature grief was first introduced as a term by Freud in his book Traumarbeit (1917). With reference to his “grief work hypothesis”, grief was presented as a process the bereaved had to go through to detach themselves from the deceased (Freud, Citation1917). This understanding of grief as a process of detachment persisted up until the nineties. Klass and Goss (Citation1999) proposed a new understanding in which the bereaved is restructuring the representation and bond with the lost one in order to restore social balance. Following this change in the understanding of grief, a revised model of coping with bereavement was proposed by Stroebe and Schut (Citation1999). This model identifies two types of stressors, loss- and restoration-oriented, and a dynamic, regulatory coping process of oscillation, whereby the individual is at times confronted with the different types of task of grieving and at other times avoids them. This model proposes that adaptive coping is composed of confrontation-avoidance of loss and restoration stressors. It also argues the need for a small dosage of grieving – that is, the need to take pauses in dealing with either of these stressors – as an integral part of adaptive coping.

The majority of research in grief has centered on grief as a reaction to bereavement. However, grief can be a reaction to all kinds of loss, which can include the death of a loved one, as well as the loss of opportunities, dreams, health, or identity (Abi-Hashem, Citation1999; Bowlby, Citation1998; Jeffreys, Citation2011). Partners experience a variety of losses during the process of adapting to a new life as a caregiving partner to a person with ABI. It is broadly recognized that these losses can lead to grief in partners (Wiwe, Citation2006; Glintborg, Citation2016). Despite caregivers’ experienced grief being well known in clinical practice, it is sparsely addressed in research (Calvete & López de Arroyabe, Citation2012). Grief is primarily represented as an aspect of other phenomena, e.g. depression in relation to becoming a caregiver, or explored as part of the general reaction to becoming a caregiver (e.g. Marwit & Kaye, Citation2006; Calvete & López de Arroyabe, Citation2012; Kitzinger & Kitzinger, Citation2014). In a study by Moretta et al. (Citation2014), 32% of participants met the criteria of prolonged grief disorder. However, the study did not explore whether the rest of the participants experienced grief.

Although little research has been conducted on grief, loss has recently received more attention in the literature in relation to ABI (e.g. Holloway, Orr & Clark-Wilson, Citation2019; Buckland, Kaminskiy & Bright, Citation2020). In the literature, there is a broad consensus that loss associated with becoming an ABI partner differs from the loss experienced in relation to losing a partner. Consequently, the grief reaction can be expected to be differentiated (Marwit & Kaye, Citation2006; Saban & Hogan, Citation2012; Carlozzi et al., Citation2015; Calvete & López de Arroyabe, Citation2012).

Loss in relation to ABI has been identified to vary over time and to be individual. Moreover, it can be ongoing, and sometimes multiple losses are connected (Saban & Hogan, Citation2012; Giovannetti et al., Citation2015; Townshend & Norman, Citation2018). Loss is dealt with while adapting to a new everyday life (Cipolletta et al., Citation2014). Both clinical experience and research indicates grief as occurring late in the rehabilitation phases: more specifically, in relation to transitions (from hospital to home) or when hope for change decreases (Wiwe, Citation2006; Moretta et al., Citation2014; Hamama-Raz et al., Citation2013).

Kreutzer, Mills and Marwitz (Citation2016) identify the losses experienced by relatives as ambiguous. Ambiguous loss is defined by Pauline Boss (Citation1999) as a loss “which occurs without closure due to the complicated and, in some cases, uncertain outcome” (Petersen & Sanders, Citation2015, p. 325). Loss associated with an acquired brain injury can be ambiguous if, for example, the survivor remains physically present, but is changed mentally. This type of loss presents a stressor for the caregiver, which can result in depression (Calvete & López de Arroyabe, Citation2012). Two recent studies exploring the experience of becoming a caregiver to a family member suffering from an ABI revealed ambiguous loss and grief as reactions (Holloway, Orr & Clark-Wilson Citation2019; Townshend & Norman, 2018).

Different experiences of loss are expected to occur as a reaction to different types of loss, but the experience of the same type of loss can differ between people, both regarding cognition and emotional expression (Moretta et al., Citation2014). Anger, loneliness and hopelessness are identified emotions in the literature in relation to the experiences of loss and grief in caregivers (Hamama-Raz et al., Citation2013; Kitzinger & Kitzinger, Citation2014).

Grief can have different manifestations and grief as a reaction changes over time (Worden, Citation2002; Jeffreys, Citation2011; Guldin, Citation2014). The manifestations of grief can be classified into four components: emotions, cognition, behavior, and somatic symptoms (Worden, Citation2002; Jeffreys, Citation2011; Guldin, Citation2014). Whether the components are interpreted as grief depends on social expectations and norms (Jeffreys, Citation2011). In this study grief is defined according to Guldin’s definition:

Grief is the physical and physiological reaction to loss of someone or something close, to which there has been an emotional attachment. The reaction encompasses a wide range of emotional, cognitive, behavioral and somatic symptoms. (Translated by the first author, Guldin, Citation2014, p. 27).

Purpose of the study

More knowledge about the partners experienced grief is needed to acknowledge the phenomenon and offer support to the partners to prevent long-term psychosocial distress. Therefore, the aim of this study is to contribute to the scientific knowledge of the experience of grief in relation to becoming a caregiver for a partner with ABI. Further, this knowledge is intended to contribute to new interventions offered to caregiving partners, and the prevention of long-term psychosocial distress among caregivers.

Design and method

The study was conducted as a phenomenological lifeworld (Lebenswelt) interview. The purpose of this method is to investigate the participants’ experience of the phenomenon in everyday life as it appears in order to gain an understanding of the phenomenon. The objective of the lifeworld interview is to describe a phenomenon as it appears for the participant. The role of the researcher is to facilitate a conversation through which the participant’s experience of the phenomenon is explored (Langdridge, Citation2007).

Sample

Following phenomenological standards, a full understanding of a phenomenon should be obtainable though a full interview with just one or a few participants (Langdridge, Citation2007). The number of participants should reflect the complexity of the phenomenon (Brinkmann & Tanggard, Citation2012; Norlyk & Martinsen, Citation2008).

The participants were recruited through a rehabilitation center and an association for ABI survivors and their relatives.

The inclusion criterion was being the spouse of an ABI survivor. Seven participants responded and all met the inclusion criterion. After having conducted the interviews, three participants were excluded, given their own life-threatening illness. The demographic data of the included participants is shown below (Table 1). Three of the participants became caregivers more than four years prior to the interview, and one did so two years prior to the interview.

Setting

Since the lifeworld interview is best conducted in a safe environment, the participants chose the location of the interview according to their individual preference. Their options were 1) at the university, 2) at the rehabilitation center or 3) in their own private home. Three participants chose their own private home, while one chose the rehabilitation center. The duration of the interview was set to be 1-1½ hours.

Interview – data collection

The lifeworld interview seeks to understand the meaning of grief as a phenomenon through everyday experiences of the participants. An interview guide was developed to guide the conversation (). Research questions was formulated based on the aim of the study and previous research. The research questions were transformed to interview questions with respect to the phenomenological standards, of an openminded conversation about the phenomenon between the interviewer and the participant.

Table 1 Participants.

Table 2 Interview guide.

Additionally, an opening question was formulated and used in all the interviews. The participants were asked to tell the interview about themselves and what had happened to their family (ABI). If the participant did not answer the question with his or her own experience, but talked about their spouse, the question was made specific to the caregiver’s experience.

All interviews were conducted by the first author, who is a trained psychologist with clinical experience in the field of psychological rehabilitation and is thus familiar with communicating with adults with various cognitive disabilities. To secure trustworthiness, the interviewer summed up on participants experiences, during the interview, to secure accurate understanding. The interviews were recorded, and field notes were taken during the interview. Afterwards the interviews were transcripted by the first author.

Analysis

Given the purpose of the study (to obtain knowledge of the experience of grief in relation to becoming a caregiver for an ABI survivor), the descriptive phenomenological method was considered to be most suitable. Therefore, the analysis was conducted following Amedeo Giorgi’s four rules for phenomenological descriptive analysis (Giorgi & Giorgi, Citation2004).

The steps are: (1) assume the phenomenological attitude, (2) read the entire written accounts for a sense of the whole, (3) delineate meaning units, (4) transform the meaning units into psychologically sensitive statements of their lived-meanings, and (5) synthesize a general psychological structure of the experience base on the constituents of the experience. (Broomé, Citation2011, p. 2)

The analysis started with an open-minded reading and a relistening of the interviews. Next, meaning units were identified and described. As a process, the meaning units were then transformed to themes that contributed to a fuller understanding of the phenomenon (Giorgi & Giorgi, Citation2004).

The analysis was conducted in collaboration between the two authors. The first author did the first round of analysis, then the second author went to the same process, to secure credibility.

Ethical considerations

To protect participants’ anonymity and confidentiality, all identifying details and specifics of the interviews have been altered. Since the study involved human participants and person-sensitive data, the project was reported to the Regional Research Ethics Committees for The North Jutland Region who found it exempt from full review. The study was also approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (Datatilsynet).

Every interview was evaluated afterwards. And the participants were asked about their experience of the interview. The participants expressed relief and insight as a result of participating in the interview, and overall considered it to be a good experience. Some even commented that it was the first time a professional had asked them how they felt and taken an interest in their experiences.

Results

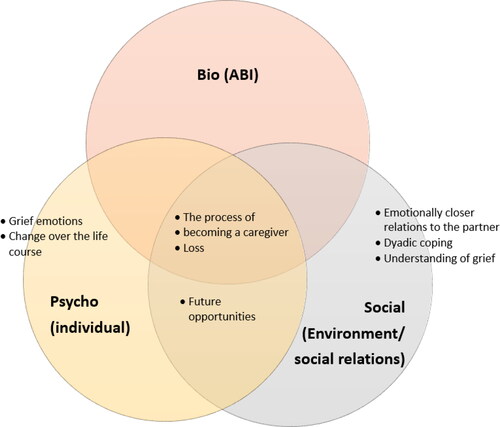

Through the phenomenological analysis a series of themes emerged. These themes can be placed in the bio-psycho-social model to understand the complexity of the phenomenon. This is seen in . Below the model, the themes will be explored.

The process of becoming a caregiver

The participants talk about becoming a caregiver as a process evolving over time, initiated by the ABI but ongoing. Ben expresses it like this: “Now, it has been six years since she had the brain injury, so, it is just – it is just an ongoing process.” Irene also mentions this ongoing process: “However, you can say it is a life crisis”. Irene further elaborates about the process and how the loss becomes clearer over time and in relation to transitions, e.g. when her partner Jens came home from the hospital: “Suddenly, it became clear that there was some loss”.

Grief emotions

Across the participants it became evident that emotions normally expected in relation to grief were also experienced by the ABI partners (Guldin, Citation2014). Central emotions for the participants were loneliness, fear, uncertainty, powerlessness, increased responsibility, guilt, and shame. However, the caregivers did not feel that there was room for their own emotions. Irene expressed it like this: “[…] at the time I had more than enough with Jens, you know. […] And that’s the thing about putting yourself aside. Packing my own emotions and my own needs away.”

Loneliness, as an emotion, was represented differently among the participants. Loneliness was essentially experienced in relation to the partner and in relation to social relations with others. Social relations are changing due to the partner’s injury. Moreover, caregivers experienced a lack of understanding from associates and society over time. Kate explains it like this: “it has taken a lot of energy, the lack of understanding from the surroundings. There is no one, because they cannot see it [invisible injury] … it is the feeling I have had”. Irene elaborates on the social aspect saying: “It was very hard socially, when my psychological reaction came, others thought that it was going better because of the physical progress in the rehabilitation.”

After the ABI incident and its aftermath, the caregivers experienced increased responsibility. In the following extract it is seen how Ben feels an expectation to take more responsibility for everyday tasks in the family: “Then it is natural that I take on a lot of things. Everyday things, in order to make the world go round.”. According to Boss (Citation1999), this increased responsibility could lead to increased emotions such as fatigue, inadequacy, and guilt since it is not always possible to meet others’ expectations and one’s own.

Loss

The feelings of loss are very different among the participants. When Ben is asked if he feels he has lost something due to his wife’s brain injury, he says: “No I do not think so. Well, it must be said that, my wife almost died. So, in that light, I do not think I have lost something, I actually think that I have been given something.”

Even though the participants did not report feelings of loss when directly asked, they talked about many forms of losses, e.g. limitations, lack of social support and changes in relations to their partner and others. Only one participant, Kate, experiences that she has lost her partner: “So, I would say, the worst thing is that I have lost my husband. Mentally, he is not there anymore.”

Emotionally closer relations to the partner

The male participants report that they have become emotionally closer to their partner after the injury. Carter express it like this: “I think we have become better at just being – and being together.” In a similar vein, Ben says: “For me, it has brought me emotionally closer to Kirsten.” The most challenging thing in the relationship is to find a balance in the new roles (e.g. spouse vs. caregiver). Carter talks about what has helped them and explains how communication has been an important factor for his wife and him: “I think it’s conversation, that is. I think that's what's helped us through it.”

Dyadic coping

Partners’ and ABI survivors’ way of coping is of great importance to the experience of grief. Three of the participants did not experience the grief to be present today, and emphasized acceptance, communication, religion/faith, positivity, acknowledgment and social support as essential aspects of their coping.

The relationship is seen to be important for the coping strategy. Carter explained what he found to be most important was to: “accept, communicate and give space [to each other]”. Ben explains how it has been important for his wife and him to choose a positive strategy, they could use together: “we choose to see the positive things in the situation … it could have been much worse”. The concept of dyadic coping also becomes apparent when Irene express how the support from their congregation did not meet their expectations. While talking about this, Irene consistently used the term we to explain the experience of lack of support from their congregation: “At that time, we were going through some rough times, and we were not able to be part of our community”.

Unmet needs for support

All the participants addressed the need for more support for caregivers, both in relation to their own psychological reactions, but also in relation to their partner and children. Kate emphasizes her support group as very helpful, since they shared a similar experience as caregivers: “It has been good. […] they are experiencing the exact same issues as me.”

Future opportunities

Future opportunities and values become central for the participants. The participants talk about new values and priorities in life. For example, Carter explains how his priorities in relation to his work have changed: “In the end [friends] are more important than making money.” In relation to the future, opportunities, dreams and freedom are important to the caregivers. Irene says: “We still have things that we want to do and then we plan them and we still have some dreams that we would like to pursue.”

Change over the life course

The participants experienced changes in their life after the ABI as a natural part of life, and their understanding of changes in life over time seemed to relate to their experience of grief. Irene explains how changes are not only due to the brain injury, but also a natural part of life as you age: “it is not only because of the brain injury, maybe we would have developed like this anyhow.” This understanding of life changes as natural affects the participants’ experience. When talking about changes, Ben expresses it like this: “This is how it was, it was necessary, so I have not seen as it as a loss.” As shown in a previous quote from Carter, participants found new meaning and value in life. Irene further explained this development: “It can be small things which [now] give us joy.”

Understanding of grief

Across the interviews, it is revealed that the experience of grief is determined by both society’s and the individual’s understanding of grief, and what is to be expected of a grief process. Both Carter and Ben say that they consider grief to be a reaction to loss, which they have not experienced: “Not a grief. For me grief is connected to loss.” However, they talk about grief on behalf of their spouse. Carter explains: “Of course it was a grief to see what she could no longer do.”

Both female participants identified grief as a reaction to the losses they had experienced. Irene describes her emotional and bodily reactions: “But I had a heavy feeling, I felt sad and unhappy, and sometimes my stomach hurts a little bit and I thought it was a little hard.” Furthermore, Irene identifies the grief she experienced in relation to becoming a caregiver as harder than the one she experienced after her father died: “I coped better with my father’s death than this. […] I think it is the worst thing I have ever experienced.”

The participants also highlighted the importance of others’ understanding of grief. Kate expresses how this was important and how she was met by others: “You cannot talk to your neighbor about it. They do not understand it, because there is nothing wrong with Niels.” The invisible consequences also affect the caregivers and their grief. Kate feels she has lost her husband. However, near the ending of the interview she expresses ambivalence and says: “Sometimes, Niels is still the same.”

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to investigate the experience of grief in relation to becoming a caregiver for a partner with ABI. This study contributes with novel knowledge about grief experiences in ABI partners. Grief is a missing focus in previous research in ABI partners (Marwit & Kaye, Citation2006; Saban & Hogan, Citation2012; Carlozzi et al., Citation2015; Calvete & López de Arroyabe, Citation2012).

Previous research in the area identifies loss following ABI as ambiguous loss (Calvete & López de Arroyabe, Citation2012; Petersen & Sanders, Citation2015), with psychological ambiguous loss especially prominent. This occurs when the partner is psychically present, but is mentally changed (Boss, Citation1999). Therefore, the severity of cognitive impairment in the ABI survivor is associated with the caregiver’s experience of ambiguous loss. In our study it can be argued that only Kate express feelings of ambiguous loss, since the other participants did not experience behavioural or personality changes in their spouses (Boss, Citation1999).

Even though not all participants reported experiences of ambiguous loss, in line with Saban and Hogan (Citation2012) all participants reported multiple losses during the rehabilitation process. The results from our study are in line with previous studies who have found that new roles and role changes in the relationship are associated with feelings of loss (Saban & Hogan, Citation2012; Carlozzi et al., Citation2015). Thus, it can be argued that caregiving partners can experience grief as a reaction to the loss they experience in relation to changes in their relationship to the ABI survivor.

Another factor seen in previous studies in ABI relations is the feeling of guilt (Carlozzi et al., Citation2015). The results from our study indicate that the participants experience guilt as to whether or not they fulfil their role as caregiving partners. In addition, guilt can evolve from internal conflicts in the family, e.g. prioritizing one’s own needs versus being the caregiver (Paulsen & Paulsen, Citation2004). Shame is closely connected to guilt and is thus an expected feeling in caregiving partners. They may experience conflict in living up to their own or others’ expectations (Paulsen & Paulsen, Citation2004). A study by Brunsden et al. (Citation2017) found that male ABI partners often experience hopelessness and powerlessness. This was also found in the male participants in our study.

Guilt, shame, and powerlessness are all emotions related to grief as a reaction to an ambiguous loss (Boss, Citation1999). The ambiguous losses can be a part of the difference between the grief after loss in connection with a death and the grief associated with becoming a caregiver to a person with ABI.

Individual, social and cultural understandings of grief

This study, like previous studies in the area, does not assume a clear definition of grief, but explores the individual experiences thereof. However, these individual experiences are always influenced by individual, social and cultural expectations of grief. Grief studies have been criticized for their sole focus on the individual level, and the omission of cultural, economic or social aspects of grief (Kofod, Citation2015).

The social and cultural influences on grief are important to consider. When a person experiences significant loss and their grief is not openly acknowledged, socially validated, or publicly mourned, we can speak of disenfranchised grief (Doka, Citation2008). Although the individual is experiencing a grief reaction, there is no social recognition that the person has a right to grieve or a claim for social sympathy or support. This is especially seen when grief occurs when there is no death. According to Doka (Citation2008), the grief of caregivers is not recognized by the society and is thus disenfranchised grief. The participants in our study express a lack of social recognition of their situation. The lack of social recognition can worsen the reaction of loss. Furthermore, as seen in our study, it can contribute to confusion as to what to call their own reactions.

Defining grief as disenfranchised emphasizes the importance of the loss. Losses can be categorized into different types (Weenolsen, Citation1988). Some type of losses are not socially accepted and therefore lead to disenfranchised grief (Doka, Citation2008). Ambiguous loss, and in particular psychosocial loss, is related to disenfranchised grief (Boss, Citation1999).

Whilst there are shared emotional responses to bereavement, the rituals of mourning and grief are shaped by our social institutions and the norms of our social groupings. That is, who we are and how we live guides the way we grieve. We are all members of various cultural, social, religious and economic groupings, and are of different ages and genders. Mourning rituals emerge within these groupings in many guises as individual members interpret the dynamic, fluid structures influenced by changing outlooks and the infusion of ideas from the prevailing social world (Doka & Davidson, Citation1998). However, loss in connection to living with disabilities is not recognized in the same way, and there are no mourning rituals. The lack of understanding and validation can lead to increased ambivalence about the loss and thus also impact the individual’s own reaction. These social and cultural circumstances surrounding the grief can increase the risk of complications (Boss, Citation1999; Doka, Citation2008). Social support, combined with social recognition of grief in relation to becoming a caregiver, is essential to the relatives of ABI survivors. Furthermore, King (Citation2015) argue, that the partners’ experienced loss is closely related to their relationship with the ABI survivor. The communication between the ABI survivor and the caregiver is of especial importance in relation to the experience of burden (King, Citation2015).

Grief responses

Wortman and Silver (Citation1989) argued, in their book The Myths of Coping With Loss, against the understanding of one proper grief response. Furthermore, they note that symptoms of depression and emotional distress are not necessarily a grief reaction, since all grief reactions are individual and different (Wortman & Silver, 1989). In our study, two of the four participants did not report feelings of grief. In line with Wortman and Silver, individual and social expectations can contribute to the participants’ experience of grief (Durkheim, Citation1915/1995). Furthermore, it can be questioned whether grief in relation to becoming a caregiving partner to a person surviving ABI is a socially recognized reaction (Doka, Citation2008).

Limitations

The purpose of this study was to investigate the experience of grief in relation to becoming a partner to an ABI survivor. However, the informants in this study is all above 50 years old and have had long lasting relationships prior the ABI. Therefore, it is worth mentioning that the explored experiences might be different in a younger population and in couples who have been in a relationship for a shorter period of time.

Conclusion

The experience of grief is determined by society’s and the individual’s understandings of grief. Grief reactions from partners to ABI survivors are, in their expression, similar to other grief reactions. However, the experience of grief is influenced by the fact that many partners experience several secondary losses during the first years after their partner acquired an ABI. Grief experiences and reactions often arise when the caregiver is confronted with changes due to the ABI.

As in grief reactions in general, ABI partners experience a range of different grief symptoms. These symptoms are all normal grief reactions. Furthermore, partners may experience feelings of powerlessness, increased responsibility, guilt, and shame. These emotions lead to an ambiguous loss and a disenfranchised grief.

Further studies

This study concludes that grief is experienced very differently by caregivers. However, the experience of grief is determined by society’s and individual understandings of grief. Further knowledge about this is needed to explore which factors affect the experience of grief amongst caregiving partners in order to develop grief models for relatives where there is no physical death.

REFERENCES

- Abi-Hashem, N. (1999). Grief, loss, and bereavement: an overview. Journal of Psychology and Christianity, 16(4), 309–329.

- Boss, P. (1999). Ambiguous Loss. Harvard University Press.

- Bowlby, J. (1998). Loss of spouse. In Attachment and Loss, Volume III: Loss (pp. 81–111). Pimlico.

- Brinkmann, S., & Tanggard, L. (2012). Interviewet: Samtalen som forskningsmetode. In Brinkmann, S., Tanggard, L. [Interview: Conversation as a research method]. Kvalitative metoder, en grundbog (pp. 29–54). Hans Reitzels Forlag.

- Braine, M. E. (2011). The experience of living with a family member with challenging behavior post Acquired Brain Injury. The Journal of Neuroscience Nursing : journal of the American Association of Neuroscience Nurses, 43(3), 156–164. https://doi.org/10.1097/JNN.0b013e3182135bb2

- Broomé, R. E. (2011). Descriptive phenomenological psychological method: an example of a methodology section from doctoral dissertation. Saybrook University San Francisco

- Brunsden, C., Kiemle, G., & Mullin, S. (2017). Male partner experiences of females with an acquired brain injury: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 27(6), 937–958. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2015.1109525

- Buckland, S., Kaminskiy, E., & Bright, P. (2020). Individual and family experiences of loss after acquired brain injury: A multi-method investigation. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2019.1708415

- Calvete, E., & López de Arroyabe, E. (2012). Depression and grief in Spanish family caregivers of people with traumatic brain injury: The roles of social support and coping. Brain Injury, 26(6), 834–843. https://doi.org/10.3109/02699052.2012.655363

- Carlozzi, N. E., Kratz, A. L., Sander, A. M., Chiaravalloti, N. D., Brickell, T. A., Lange, R. T., Hahn, E. A., Austin, A., Miner, J. A., & Tulsky, D. S. (2015). Health-related quality of life in caregivers of individuals with traumatic brain injury: development of a conceptual model. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 96(1), 105–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2014.08.021

- Cipolletta, S., Gius, E., & Bastianelli, A. (2014). How the burden of caring for a patient in a vegetative state changes in relation to different coping strategies. Brain Injury, 28(1), 92–96. https://doi.org/10.3109/02699052.2013.857789

- Danish Board of Health (Sundhedsstyrelsen) (2011). Hjerneskaderehabilitering – en medicinsk teknologivurdering Brain Injury rehabilitation – a Health Technology

- Doka, K. J. (2008). Disenfranchised grief in historical and cultural perspective. In Stroebe, M. S., Hansson, R. O., Schut, H. & Stroebe, W. (Eds.) (2008) Handbook of Bereavement Research and Practice (pp. 223–240). American Psychological Association.

- Doka, K. J., & Davidson, J. D. (1998). Who we are, how we grieve. In K.J. Doka & J.D. Davidson (Eds.) Living with Grief: Who We Are and How We Grieve (pp. 1–5). Brunner/Mazel.

- Durkheim, E. (1915/1995). The Piacular Rites and the Ambiguity of the Notion of the Sacred. In: The Elementary Forms of Religious Life (pp. 392–417). Free Press.

- Eilertsen, G., Kirkevold, M., & Bjørk, I. T. (2010). Recovering from a stroke: a longitudinal, qualitative study of older Norwegian women. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 19(13-14), 2004–2013. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.03138.x

- Freud, S. (1917). Mourning and melancholia. In: Collected Papers vol. IV. Sigmund Freud. Hogarth Press.

- Giorgi, A., & Giorgi, B. (2004). Phenomenology. In Smith, J. (Ed.), Qualitative Psychology (pp.25–50). SAGE Publications.

- Giovannetti, A. M., Černiauskaitė, M., Leonardi, M., Sattin, D., & Covelli, V. (2015). Informal caregivers of patients with disorders of consciousness: Experience of ambiguous loss. Brain Injury, 29(4), 473–480. https://doi.org/10.3109/02699052.2014.990514

- Glintborg, C. (2016). Er det normalt at have det sådan her, når man er pårørende til en person med en erhvervet hjerneskade? [Are these normal reactions when you are a relative to a person with brain injury?]. HjerneSagen, 23(4), 15–16.

- Guldin, M.-B. (2014). Tab og sorg. En grundbog for professionelle. [Loss and grief. A textbook for professionals]. Hans Reitzels Forlag.

- Hamama-Raz, Y., Zabari, Y., & Buchbinder, E. (2013). From hope to despair, and back: being the wife of a patient in a persistent vegetative state. Qualitative Health Research, 23(2), 231–240. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732312467537

- Holloway, M., Orr, D., & Clark-Wilson, J. (2019). Experiences of challenges and support among family members of people with acquired brain injury: a qualitative study in the UK. Brain Injury, 33(4), 401–411. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699052.2019.1566967

- Jeffreys, J. S. (2011). Helping Grieving People – When Tears are Not Enough. Routledge.

- Klass, D., & Goss, R. (1999). Spiritual bonds to the dead in cross-cultural and historical perspective: Comparative religion and modern grief. Death Studies, 23(6), 547–567. https://doi.org/10.1080/074811899200885

- Kofod, E. H. (2015). Sorg som graensediagnose. [Grief as a grey zone diagnose]. In: Brinkmann, S. & Petersen, A. (Eds.). Diagnoser. Perspektiver, kritik og discussion (pp. 229–246). Forlaget Klim.

- King, B. A. (2015). Grief experience among family caregivers following traumatic brain injury: the role of survivor personality change, perceived social support, and meaning reconstruction [University of Windsor (Canada)]. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 2015. 3723789.

- Kitzinger, C., & Kitzinger, J. (2014). Grief, anger and despair in relatives of severely brain injured patients: responding without pathologising. Clinical Rehabilitation, 28(7), 627–631. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215514527844

- Kreutzer, J. S., Mills, A., & Marwitz, J. H. (2016). Ambiguous loss and recovery after traumatic brain injury. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 8(3), 386–397. https://doi.org/10.1111/jftr.12150

- Langdridge, D. (2007). Phenomenological Psychology. Theory, Research and Method. England. Pearsen Education Limited.

- Marwit, S., & Kaye, P. (2006). Measuring grief in caregivers of persons with acquired brain injury. Brain Injury, 20(13-14), 1419–1429. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699050601082214

- Moretta, P., Estraneo, A., De Lucia, L., Cardinale, V., Loreto, V., & Trojano, L. (2014). A study of the psychological distress in family caregivers of patients with prolonged disorders of consciousness during in-hospital rehabilitation. Clinical Rehabilitation, 28(7), 717–725. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215514521826

- Murray, C. I., & Broadus, A. D. (2011). Family transitions and ambiguous loss. In Craft-Rosenberg, M. & Pehler, S-R (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Family Health (pp. 502–503). Sage Publications.

- Norlyk, A., & Martinsen, B. (2008). Faenomenologi som forskningsmetode [Phenomenology as a research method]. Sygeplejersken, 13, 70–74.

- Norsk Hjerneslagregister (2018). Årsrapport Norsk Hjerneslagregister for 2018. Med plan for forbedringstiltak. Nasjonalt sekretariat for Norsk hjerneslagregister, Seksjon for medisinske kvalitetsregistre St. Olavs hospital HF 01.10.2019

- Paulsen, M. H., & Paulsen, L. J. (2004). Pårørende i sorg og krise. Stiftelsen Psykiatrisk Opplysning.

- Petersen, H., & Sanders, S. (2015). Caregiving and traumatic brain injury: coping with grief and loss. Health & Social Work, 40(4), 325–328. https://doi.org/10.1093/hsw/hlv063

- Saban, K. L., & Hogan, N. S. (2012). Female caregivers of stroke survivors: coping and adapting to a life that once was. The Journal of Neuroscience Nursing : journal of the American Association of Neuroscience Nurses, 44(1), 2–14. https://doi.org/10.1097/JNN.0b013e31823ae4f9

- Stroebe, M., & Schut, H. (1999). The dual process model of coping with bereavement: Rationale and description. Death Studies, 23(3), 197–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/074811899201046

- Townshend, J., & Norman, A. (2018). The Secondary Impact of Traumatic Brain Injury. The Family Journal, 26(1), 77–85. 10.1177/1066480717752905

- Weenolsen, P. (1988). Loss. In Transcendence of Loss over the Life Span (pp.19–58). Hemisphere Publishing Corporation.

- Wiwe, L. B. (2006). Håndbog for pårørende – til personer med hjerneskade. [Handbook for relatives of persons with brain injury]. The Brain Injury Association.

- Worden, J. W. (2002). Grief Counseling and Grief Therapy: A Handbook for the Mental Health Practitioner. Springer.

- Wortman, C. B., & Silver, R. C. (1989). The myths of coping with loss. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 57(3), 349–357. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.57.3.349