Abstract

One of the main theoretical perspectives for understanding the mechanism responsible for the extensively reported mental and physical health disparities between divorcees and continuously married populations is the Selection Perspective. This perspective posits that due to “problematic personal characteristics of poorly adjusted people”, they are at higher risk for both divorce and poorer health outcomes. A criticism of this perspective is that it may contribute to divorce-related stigma, especially if there is insufficient empirical data to support it. The present study compared the Five Factor Model personality scores of 676 recently divorced Danes (Nwomen = 446, Nmen = 230) to the general Danish population normative data of the same instrument. Divorced women reported higher conscientiousness than the Danish norm, whereas divorced men had higher neuroticism scores than the Danish norm. Divorced participants of both genders had higher agreeableness and openness levels than the Danish norms. Though the differences were significant, they were small and did not provide compelling evidence for the Selection Perspective’s assumption, meaning that the recently divorced participants’ personality characteristics did not differ from the general population in ways that could be considered to constitute problematic personal characteristics. Future research should further evaluate the adequacy of the Selection Perspective.

Keywords:

Introduction

The self-report reasons for why people divorce in Denmark range from violence and substance abuse to lack of love, communication problems, and personality (Strizzi et al., Citation2020). Individuals’ experiences with divorce are heterogeneous and for many leaving a distressing relationship can positively impact mental health while for others physical and mental health are negatively impacted (e.g. Amato, Citation2000, Citation2010, Citation2014). Understanding why people choose to end a relationship, and what may predispose some individuals to divorce as opposed to remaining continuously married, is of interest to prevent the negative consequences associated with divorce documented in the literature (Gravningen et al., Citation2017; Strizzi et al., Citation2020).

Two diverging theoretical perspectives seek to understand the mechanism responsible for the previously found associations between divorce and health (Amato, Citation2000). The first and most widely used is The Divorce Stress-Adjustment Perspective (DSAP) (Amato, Citation2000, Citation2014). The DSAP holds that the divorce process triggers a series of changes (such as single parenting/loss of custody, economic decline, and changes in social support) which can lead to poor psychological adjustment and adverse health outcomes and that this pathway is moderated by protective factors including resources and demographic characteristics. Recent research supports this theoretical perspective, finding that socio-demographic characteristics and structural resources serve as moderators of post-divorce adjustment trajectories (e.g. Cipric et al., Citation2021; Hald et al., Citation2022; Strizzi et al., Citation2022).

A contrasting (perhaps controversial and/or outdated) theory, the Selection Perspective, posits that “poorly adjusted people” (i.e. individuals with “problematic personal and social characteristics”) are predisposed to divorce and select out of marriage. That is, people who divorce bring traits to their marriages that cause the divorce and they and their children face adverse health outcomes as a result of both these characteristics and the stressful consequences of the divorce itself (Amato, Citation2000, Citation2010, Citation2014). These factors compound the risks for poorer health outcomes as the effects of these problematic characteristics impact health before the divorce as well as the stressful impact of the divorce itself. This theoretical assumption may be reflected in the 12% of divorcees who experience health difficulties years prior to and after their divorce (Malgaroli et al., Citation2017; Perrig-Chiello et al., Citation2015). The research related to the Selection Perspective has almost exclusively regarded whether characteristics of divorcees such as delinquency, antisocial behavior, and mental health concerns are associated with divorce, which is then in turn associated with poor health outcomes for the divorcees and their children after divorce (see Amato, Citation2000, Citation2010, Citation2014 for reviews). The application of this theoretical perspective has primarily focused on seeking to explain psychological and physical health disparities between the children of divorced parents and the children of continuously married individuals by way of the mechanism that divorcees are distinct from their continuously married counterparts (i.e. they possess traits that put them and children at higher risk of adverse outcomes); less research has focused on the divorcees themselves.

However, the key component of this perspective—that the divorcees themselves possess characteristics that cause the divorce and adverse health effects - has received little scrutiny. That is, for the Selection Perspective to adequately explain the documented post-divorce health disparities, it must be established that divorcees select themselves out of marriage because they possess “problematic” traits. If due scientific scrutiny is applied to the Selection Perspective, in terms of personality: What would constitute “problematic personal characteristics”?

One way to ascertain whether a divorced population possesses “problematic traits” in terms of personality is to compare our sample of recently divorced Danes to the instrument norms from a general population. This allows us to evaluate whether the personality trait level scores of a recently divorced population reflect typical or expected levels of a normal or typical Danish population or if they reflect atypical scores. Comparisons to normative data are common in medicine and clinical practice as a way to evaluate whether an individual’s or a population’s scores on a given measure differ from a diverse representative general or background population (i.e. are the scores reflective of normal, typical, or healthy values) (Kendall & Sheldrick, Citation2000; O'Connor, Citation1990). Normative comparison of divorcees would allow for some evidence to evaluate the key component (that divorcees select out of marriage and face adverse health consequences due to their problematic characteristics) of the Selection Perspective which has not received adequate scrutiny.

This assumption that divorcees possess “problematic” traits which lead to divorce and adverse health outcomes for them, and their children can be deeply problematic for several reasons. Firstly, there is little empirical support for the existence of significant “problematic” traits that characterize divorcees. Secondly, how does one define “problematic characteristics”? Third, this perspective becomes even more problematic when considering that divorce has become a common occurrence, with the divorce rate in most industrialized countries stably remaining around 40–50% for the past decades (Korhonen & Puhakka, Citation2021). Therefore, if divorce is becoming so commonplace that it could be the norm, how do divorcees differ from the rest of the population? Finally, the very assumption that divorcees must or somehow differ from the continuously married population and that due to these “problematic” differences their marriages end is stigmatizing to a large portion of the population that may already be experiencing stigma related to their divorce (Konstam et al., Citation2016). This theory is cited in the divorce literature, thus, it ought to be explored from a scientific perspective and empirical evidence is necessary to determine whether the Selection Perspective can be supported.

Personality and divorce

Following the Five Factor Model, the predominant model for personality structure in the field of psychology (John, Citation2021), the facets of personality are neuroticism, extraversion, openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness. While all of the personality facets can be associated with a number of positive outcomes, there may also be downsides and undesirable outcomes to all of the facets, even those that can be considered positive like conscientiousness (e.g. Jackson & Hill, Citation2019; Klein et al., Citation2011; Markon et al., Citation2005). Specifically, high neuroticism has been associated with a wide range of poor health outcomes (Lahey, Citation2009). We have previously found that individuals with high neuroticism report worse mental health in terms of symptoms of anxiety, depression, somatization, and stress immediately following divorce and over the first 12 months post-divorce compared with their counterparts with low neuroticism (Hald et al., Citation2022).

Studies have assessed whether and which personality facets are related to an increased risk of divorce although overall, the research is scant and equivocal. Much of the early research employed instruments based on personality models other than the 5-factor model, and as the literature is sparse, these studies are also considered. This early work suggested that, for men, increased extraversion (Bentler & Newcomb, Citation1978; Eysenck, Citation1980; Kelly & Conley, Citation1987) and lower conscientiousness (Kurdek, Citation1993) were associated with an increased risk of divorce. For men and women, high neuroticism or neuroticism-related traits have also been found to be a particularly strong predictor of divorce (Eysenck, Citation1980; Jocklin et al., Citation1996; Kelly & Conley, Citation1987; Kurdek, Citation1993; Roberts et al., Citation2007; Solomon & Jackson; 2014). Later work that accounted for all the facets of the five-factor model found that low agreeableness, low conscientiousness, higher neuroticism, and higher openness predicted relationship dissolution (Solomon & Jackson, Citation2014). However, these studies mainly compare individuals of distinct relationship statuses to determine whether and which personality dimensions are associated with an increased risk of divorce. To our knowledge, no studies have compared a divorced population’s Five Factor Model personality profiles to general population normative data to determine whether they in fact differ from the norm.

Why might personality predispose individuals to relationship dissolution? There may be several explanations. The first explanation could be through the relationships between personality, marital satisfaction, and divorce. Personality is associated with marital satisfaction and those high in neuroticism and low in conscientiousness have been found to be less satisfied with their marriage (O'Meara & South, Citation2019; Sayehmiri et al., Citation2020). Further, low relationship satisfaction can lead to a divorce (Solomon & Jackson, Citation2014). In this way, those with high neuroticism and low conscientiousness may be more likely to divorce as a result of lower relationship satisfaction. Moreover, the interaction and dynamics of the personalities of the two individuals in the dyad of a couple may also be important in explaining relationship satisfaction and quality (Solomon & Jackson, Citation2014; Shiota & Levenson, Citation2007). Thus, the combination of personality traits of the two people in the relationship (e.g. similar levels of conscientiousness; Shiota & Levenson, Citation2007) may result in lower relationship satisfaction and a higher likelihood of divorce.

The second possible explanation for how personality facets may predispose some individuals to divorce is neuroticism. Lahey (Citation2009) hypothesized that neuroticism is associated with poorer mental health because highly neurotic individuals’ behavior and interactions increase the number of negative life events and daily experiences. In terms of relationship dissolution, those with higher neuroticism may be at a higher risk of divorce because their behavior and interactions with their spouses result in conflict-filled, unstable relationships that are more likely to dissolve.

The present study aims to compare the Five Factor Model personality scores of recently divorced Danes to the normative data of the same instrument for the Danish population. While a causal relationship cannot be determined with cross-sectional data, if the Selection Perspective does explain the relationship between divorce and poorer health outcomes, we should expect significant differences from the normative population that would constitute “problematic personal characteristics” per the key assumption of the Selection Perspective. While some research has assessed personality traits that are associated with an increased risk of divorce, these do not necessarily constitute “problematic personal characteristics”. Based on research and theory regarding how specific personality constellations may predispose individuals to relationship dissolution, we anticipate finding significantly higher levels of neuroticism, lower agreeableness, and lower conscientiousness among recently divorced Danes, when compared to the normative data. If the findings are null, then the study may serve to reduce divorce-related stigma.

Participants and Procedure

Participants

A total of 676 (Nwomen = 446, Nmen = 230) people participated in the study. Participants were an average of 45 years old (SD = 8.66), had been married for an average of 13 years (SD = 8.02), were experiencing their first divorce (87.7%), and had two children (50.9%). Additionally, they had a medium level of education (medium length, higher education, and bachelor’s degrees; 37.3%) and an average level of income (4500–7500 USD per month; 43.5%). Female participants were slightly younger and had higher educational attainment and incomes than male participants (see ).

Table 1 Participant sociodemographic information (N = 676, men n = 230, women n = 446).

Compared with all people who divorced in Denmark during the study period, using data obtained from Statistics Denmark, our sample was representative in terms of age and marriage duration (p > .05). However, there were more female participants (χ2 (1, n = 676) = 69.02, p < 0.001)), higher educated participants (χ2 (2, n = 676) = 1135.23, p < 0.001)), participants with a higher income (t(675) = 2.50 p = .013)), and study participants been divorced fewer times (t(675) = −5.91, p < 0.001)).

Normative data were obtained from the Danish NEO-PI-3 manual, for information regarding the normative sample population, see Skovdahl-Hansen et al. (Citation2004).

Procedure

The data come from the 12-month online intervention RCT “Cooperation after Divorce” (CAD) study. The data used for this paper consist of sociodemographic and personality variables which were assessed initially and only once. Recruitment of participants was carried out online, in collaboration with the Danish State Administration (DSA), which sent an invitation, informed consent, and the link to the study together with the divorce decree to the people who formalized their divorce during the study period. Participants were required to have Danish citizenship as well as to read and write in the Danish language and have access to the Internet. All data were stored on a secure server and anonymized. This research was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency and was exempt from further ethical evaluations following the rules and regulations as set forth by the Scientific Ethical Committees of Denmark. For detailed information regarding the CAD intervention RCT, refer to Sander et al., Citation2024).

Measures

Personality was assessed with the Danish language version of the NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI-3) (Skovdahl-Hansen et al., Citation2004) at the 1-month post-divorce time collection. The NEO-FFI-3 is a well-validated questionnaire comprising 60 items and is a short version of the Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO PI-R) (Costa & McCrae, Citation1992), which assesses the Big Five personality dimensions of neuroticism, extraversion, openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness on a five-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) in the Danish version (the American version responses are 0–4). The total score range for the 12 items included for each personality dimension is 12–60. The internal consistency was high for the present study (α = .73–.88). Normative data were obtained from the Danish NEO-PI-3 manual (Skovdahl-Hansen et al., Citation2004).

Results

presents the correlations between the personality dimensions, by gender. For women, agreeableness was associated with greater conscientiousness and openness, and less neuroticism. Conscientiousness was associated with more extraversion, and both were associated with less neuroticism. Extraversion was also associated with more openness. For men, openness was associated with more agreeableness, conscientiousness, and extraversion, and extraversion was associated with more conscientiousness. Neuroticism was associated with less conscientiousness and extraversion. Independent samples t-tests conducted in SAS revealed that newly divorced women were higher on agreeableness (t(674) = 6.51, p <.001, Cohen’s d = .50), conscientiousness (t(674) = 2.21, p =.027, Cohen’s d = .17), neuroticism (t(674) = 4.19, p <.001, Cohen’s d = .32), and openness (t(674) = 2.21, p =.028, Cohen’s d = .17), relative to newly divorced men. There were no significant differences with respect to extraversion.

Table 2 Descriptive analyses of the outcome variables (N = 676, men n = 230, women n = 446).

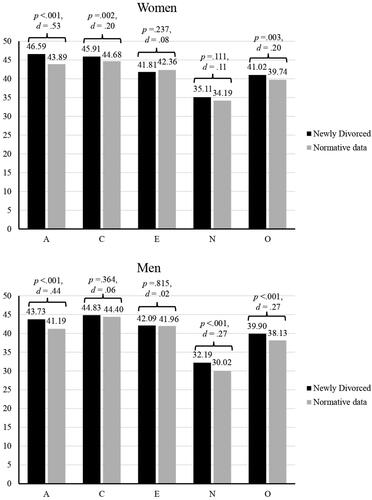

Independent samples t-tests were conducted to compare personality scores from the CAD intervention study to the Danish personality norms (McCrae & Costa, Citation2014). overviews the findings and the supplemental materials contain the Excel calculations. We found that for women, newly divorced people scored higher on agreeableness (t(897) = 7.94, p <.001, Cohen’s d = .53), conscientiousness (t(897) = 3.05, p = .002, Cohen’s d = .20), and openness (t(897) = 2.97, p = .003, Cohen’s d = .20), relative to the Danish national norms for women. There were no significant differences for extraversion or neuroticism.

Figure 1 Personality scores at 1-month post-juridical divorce compared with national norm data, stratified by gender.

Note. A = agreeableness, C = conscientiousness, E = extraversion, N = neuroticism, O = openness

With respect to newly divorced men, they scored higher on agreeableness (t(807) = 5.57, p <.001, Cohen’s d = .44), neuroticism (t(807) = 3.36, p <.001, Cohen’s d = .27), and openness (t(807) = 3.51, p <.001, Cohen’s d = .27), relative to the Danish national norms for men. There were no significant differences in conscientiousness or extraversion.Footnote1

Discussion

This study, as a first, aimed to compare the five-factor model personality characteristics of a recently divorced cohort to general population normative data to assess a key assumption of the Selection Perspective. Within this theoretical understanding of post-divorce health sequelae, divorcees select themselves out of relationships due to “problematic personal characteristics”, which then, in turn, put them at a higher risk for poorer health. That is, divorcees differ from the rest of the population in a problematic way which leads to divorce and subsequent health consequences. Research and theory suggest that namely higher levels of neuroticism predispose individuals to divorce (Eysenck, Citation1980; Jocklin et al., Citation1996; Kelly & Conley, Citation1987; Kurdek, Citation1993; Roberts et al., Citation2007; Solomon & Jackson; 2014). Moreover, high neuroticism is the personality trait that is most clearly documented to be associated with poorer health (Lahey, Citation2009). Further, a previous study has found that those scoring higher on neuroticism report poorer mental health but experience a sharper decrease in symptom severity over the course of the first year post-divorce than those with lower neuroticism (Hald et al., Citation2022). Thus, we expected to find significantly higher neuroticism levels among recent divorcees when compared to normative data. In the present study, only men scored slightly higher (M = 32.19) than the normative mean (M = 30.02). Although significant differences were found on the sample level, the effect sizes were small (d = .27). The mean difference of approximately 2 points on an instrument, for which scores can range from 12 to 60, is likely not meaningful.

Male and female participants in our sample scored higher on agreeableness and openness than the normative population for the instrument, and women scored higher on conscientiousness. Previous research found low conscientiousness and low agreeableness (Kurdek, Citation1993; Solomon & Jackson, Citation2014) to be predictive of divorce, so our results diverge from the literature. Specifically, Solomon and Jackson (Citation2014) followed a large sample over 10 years to evaluate the predictive power of personality in relationship dissolution by comparing continuously coupled participants and individuals whose relationships ended. Our findings of higher agreeableness and conscientiousness (for women) are contrary to their results of low conscientiousness and lower agreeableness having small but significant associations with the risk of relationship dissolution. Notably, our finding of higher openness among the sample of recent divorcees is similar to that of another study (Solomon & Jackson, Citation2014), which found that higher levels of openness were associated with a higher risk of divorce. It may be that people with higher levels of openness may be more open to new relationship experiences, which may predispose them to divorce; future research should seek to examine the mechanisms for why higher openness is associated with divorce.

While we did find statistically significant differences, our results do not provide compelling support for the Selection Perspective for two reasons. First, the differences between the recently divorced cohort and the normative data for the general Danish population cannot be classified as problematic personal characteristics, as being agreeable, conscientious, and open to new experiences are generally considered positive characteristics (Lamers et al., Citation2012). While an excessively high level of conscientiousness and agreeableness can be problematic in terms of mental health outcomes (Klein et al., Citation2011; Jackson & Hill, Citation2019; Markon et al., Citation2005), the mean difference levels from the norm populations were not indicative of high/problematic trait levels (i.e. the difference was typically no more than 2–3 points). Secondly, the magnitudes of the significant differences found are small to moderate, ranging from d = .20 to d =.53. Thus, it is not prudent to assume that these generally small effect sizes translate into a meaningful distinction between our recently divorced participants and the Danish normative population. For these reasons, we cannot interpret these results as support for the Selection Perspective. More research is needed to further assess the adequacy of the Selection Perspective in the study of post-divorce adjustment.

Individuals’ experiences with divorce are diverse and heterogeneous, leaving a distressing relationship may be a positive experience, and the life changes provoked by the dissolution can also be distressing. While perceptions of divorce are changing and it is increasingly seen as more acceptable (Fucik, Citation2021), divorcees may continue to experience stigma, and perceptions of blame, failure, or inadequacy related to their divorce (Konstam et al., Citation2016). The infiltration of the Selection Perspective into popular culture may contribute to these negative sentiments for divorcees. The findings of our study provide a small contribution to demonstrating that in terms of personality, we did not find evidence of “problematic characteristics” in the sample and thus, these results may serve to reduce the stigma associated with divorce.

Limitations

The key limitation of the present study is the timing of data collection; participants responded to the NEO-FFI-3 approximately one-month post-divorce. It could be postulated that the participant’s scores may reflect changes in personality due to the relationship dissolution. That is, perhaps the process leading up to and after the divorce led to increased anxiety and stress for the participants, which may have resulted in participants evincing higher levels of neuroticism. Moreover, changes to their living circumstances may lead new divorcees to work harder and exhibit more discipline, resulting in higher scores on the measure of conscientiousness. Lastly, going through the divorce may lead divorcees to develop more open views about different issues, including family constellations, child-rearing, and interpersonal relations, which could result in a higher level of openness to experience. However, research regarding post-divorce personality development indicates this is improbable as divorce is not a strong nor consistent predictor of personality change (Allemand et al., Citation2015; Asselmann & Specht, Citation2020; Costa et al., Citation2000; Roberts & Bogg, Citation2004; Specht et al., Citation2011).

A second limitation of the present study is the possible self-selectivity of our sample, which could have caused selection bias and affected the results. We have not been able to assess whether people who joined the study differed in their personality traits from the background population of people who divorced during the study period. However, we did find our sample to consist of higher educated participants and participants of higher income than the background population of divorcing individuals. Associations between socioeconomic status and Big Five traits have been previously reported. Specifically, higher SES is associated with higher conscientiousness, agreeableness, and openness (Chapman et al., Citation2009; Heckman & Kautz, Citation2012; Jonassaint et al., Citation2011), and lower neuroticism (Kajonius & Carlander, Citation2017). These factors could have inflated the differences between the scores in our sample and the normative trait levels. The generalizability of these results is yet to be determined.

A final limitation is that the normative data employed for comparison, which was obtained from the Danish NEO-PI-3 manual (Skovdahl-Hansen et al., Citation2004), does not specify the civil status of the participants. A matched-control design including a wider range of socio-demographic variables for the matching procedure would have been a stronger methodological approach but was not possible with the available data.

Conclusions

This study compared the Five Factor Model personality scores of recently divorced Danes to the normative data of the same instrument for the Danish population in order to explore the Selection Perspective’s assumption that divorcees differ from the rest of the population in ways that constitute “problematic personal characteristics”. We found small and statistically significant differences. Divorced men had slightly higher scores on neuroticism as compared to the Danish norm, whereas divorced women indicated higher levels of contentiousness than the Danish norm. Divorced participants of both genders reported higher levels of agreeableness and openness compared to Danish norms. These findings do not support the assumption of the Selective Perspective.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (14.8 KB)Disclosure statement

For due diligence, we would like to declare that the University of Copenhagen, Denmark, where the majority of authors have worked, owns the digital intervention platform while two of the co-authors (Gert Martin Hald and Søren Sander) hold the commercial license rights to the platform through the Company ‘Cooperation after Divorce’ (Samarbejde Efter Skilsmisse ApS).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Ancillary analyses were conducted based on a reviewer’s suggestion to explore the role of socio-demographic variables in personality scores. We found the suggestion interesting and that the results, though not fully in line with the scope of the present paper, were of scientific value. Therefore, we present these as supplementary findings. We created a variable for the raw difference in divorced participants’ personality scores from the Danish norm; scores were able to be either positive or negative, to the extent that a participant’s score was above or below the norm. Linear regression analyses were performed for each of the five personality differences from the norm, with gender, education level, income, marriage duration, and the number of times divorced as the predictor variables. The results were null for agreeableness. For conscientiousness, being a woman, having a higher income, and having a longer marriage duration were associated with larger and higher differences from the Danish normative value. In terms of extraversion, higher income was significantly linked with higher and larger differences from the norm. Being a woman, having a higher educational level, higher income, longer marriage, and more previous divorces were significantly associated with higher and larger differences from the norm in neuroticism. Only higher educational level was linked with higher and larger differences in openness (see Supplemental Table 1).

References

- Allemand, M., Hill, P. L., & Lehmann, R. (2015). Divorce and personality development across middle adulthood: Divorce and personality development. Personal Relationships, 22(1), 122–137. https://doi.org/10.1111/pere.12067

- Amato, P. (2000). The consequences of divorce for adults and children. Journal of Marriage and Family, 62(4), 1269–1287. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.01269.x

- Amato, P. R. (2010). Research on divorce: Continuing trends and new developments. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72(3), 650–666. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00723.x

- Amato, P. (2014). The consequences of divorce for adults and children: An update. Drustvena Istrazivanja, 23(1), 5–24. https://doi.org/10.5559/di.23.1.01

- Asselmann, E., & Specht, J. (2020). Taking the ups and downs at the rollercoaster of love: Associations between major life events in the domain of romantic relationships and the Big Five personality traits. Developmental Psychology, 56(9), 1803–1816. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0001047

- Bentler, P. M., & Newcomb, M. D. (1978). Longitudinal study of marital success and failure. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 46(5), 1053–1070. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.46.5.1053

- Chapman, B. P., Fiscella, K., Kawachi, I., & Duberstein, P. R. (2009). Personality, socioeconomic status, and all-cause mortality in the United States. American Journal of Epidemiology, 171(1), 83–92. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwp323

- Cipric, A., Štulhofer, A., Øverup, C. S., Strizzi, J. M., Lange, T., Sander, S., & Hald, G. M. (2021). Does one size fit all? Socioeconomic moderators of post-divorce health and the effects of a post-divorce digital intervention. Psychosocial Intervention, 30(3), 163–173. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2021a6

- Costa, P. T., Jr., Herbst, J. H., McCrae, R. R., & Siegler, I. C. (2000). Personality at midlife: Stability, intrinsic maturation, and response to life events. Assessment, 7(4), 365–378. https://doi.org/10.1177/107319110000700405

- Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1992). Normal personality assessment in clinical practice: The NEO personality inventory. Psychological Assessment, 4(1), 5–13. https://doi.org/10.1037//1040-3590.4.1.5

- Eysenck, H. J. (1980). Personality, marital satisfaction, and divorce. Psychological Reports, 47(3_suppl), 1235–1238. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1980.47.3f.1235

- Fucik, P. (2021). Trends in divorce acceptance and its correlates across European countries. Sociologický ČAsopis, 56(6), 863–895. https://doi.org/10.13060/CSR.2020.053

- Gravningen, K., Mitchell, K. R., Wellings, K., Johnson, A. M., Geary, R., Jones, K. G., Clifton, S., Erens, B., Lu, M., Chayachinda, C., Field, N., Sonnenberg, P., & Mercer, C. H. (2017). Reported reasons for breakdown of marriage and cohabitation in Britain: Findings from the third National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal-3). PloS One, 12(3), e0174129. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0174129

- Hald, G. M., Wimmelmann, C. L., Øverup, C. S., Cipric, A., Sander, S., & Strizzi, J. M. (2022). Mental health trajectories after juridical divorce: Does personality matter? Journal of Personality, 91(2), 426–440. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12737

- Heckman, J. J., & Kautz, T. (2012). Hard evidence on soft skills. Labour Economics, 19(4), 451–464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2012.05.014

- Jackson, J. J., & Hill, P. L. (2019). Lifespan development of conscientiousness. In D. P. McAdams, R. L. Shiner, & J. L. Tackett (Eds.), Handbook of personality development (pp. 153–170). Guilford Press.

- Jocklin, V., McGue, M., & Lykken, D. T. (1996). Personality and divorce: A genetic analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71(2), 288–299. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.71.2.288

- John, O. P. (2021). History, measurement, and conceptual elaboration of the Big‑Five trait taxonomy. In O. P. John, & R. W. Robins (Eds.), Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research. Guilford Press.

- Jonassaint, C. R., Siegler, I. C., Barefoot, J. C., Edwards, C. L., & Williams, R. B. (2011). Low life course socioeconomic status (SES) is associated with negative NEO PI-R personality patterns. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 18(1), 13–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-009-9069-x

- Kajonius, P. J., & Carlander, A. (2017). Who gets ahead in life? Personality traits and childhood background in economic success. Journal of Economic Psychology, 59, 164–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2017.03.004

- Kelly, E. L., & Conley, J. J. (1987). Personality and compatibility: A prospective analysis of marital stability and marital satisfaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52(1), 27–40. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.52.1.27

- Kendall, P. C., & Sheldrick, R. C. (2000). Normative data for normative comparisons. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(5), 767–773.

- Klein, D. N., Kotov, R., & Bufferd, S. J. (2011). Personality and depression: Explanatory models and review of the evidence. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 7(1), 269–295. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032210-104540

- Konstam, V., Karwin, S., Curran, T., Lyons, M., & Celen-Demirtas, S. (2016). Stigma and divorce: A relevant lens for emerging and young adult women? Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 57(3), 173–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/10502556.2016.1150149

- Korhonen, M., & Puhakka, M. (2021). The behavior of divorce rates: A smooth transition regression approach. Journal of Time Series Econometrics, 13(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1515/jtse-2019-0018

- Kurdek, L. A. (1993). Predicting marital dissolution: A 5-year prospective longitudinal study of Newlywed couples. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64(2), 221–242. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.64.2.221

- Lahey, B. B. (2009). Public health significance of neuroticism. The American Psychologist, 64(4), 241–256. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015309

- Lamers, S. M. A., Westerhof, G. J., Kovács, V., & Bohlmeijer, E. T. (2012). Differential relationships in the association of the Big Five personality traits with positive mental health and psychopathology. Journal of Research in Personality, 46(5), 517–524. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2012.05.012

- Malgaroli, M., Galatzer-Levy, I. R., & Bonanno, G. A. (2017). Heterogeneity in trajectories of depression in response to divorce is associated with differential risk for mortality. Clinical Psychological Science: A Journal of the Association for Psychological Science, 5(5), 843–850. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702617705951

- Markon, K. E., Krueger, R. F., & Watson, D. (2005). Delineating the structure of normal and abnormal personality: An integrative hierarchical approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88(1), 139–157. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.88.1.139

- McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T. (2014). NEO Personality Inventory-3 Klinisk Version. Hogrefe.

- O'Connor, P. J. (1990). Normative data: Their definition, interpretation, and importance for primary care physicians. Family Medicine, 22(4), 307–311.

- O'Meara, M. S., & South, S. C. (2019). Big Five personality domains and relationship satisfaction: Direct effects and correlated change over time. Journal of Personality, 87(6), 1206–1220. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12468

- Perrig-Chiello, P., Hutchison, S., & Morselli, D. (2015). Patterns of psychological adaptation to divorce after a long-term marriage. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 32(3), 386–405. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407514533769

- Roberts, B. W., & Bogg, T. (2004). A longitudinal study of the relationships between conscientiousness and the social-environmental factors and substance-use behaviors that influence health. Journal of Personality, 72(2), 325–354. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-3506.2004.00264.x

- Roberts, B. W., Kuncel, N. R., Shiner, R., Caspi, A., & Goldberg, L. R. (2007). The power of personality: The comparative validity of personality traits, socioeconomic status, and cognitive ability for predicting important life outcomes. Perspectives on Psychological Science: A Journal of the Association for Psychological Science, 2(4), 313–345. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6916.2007.00047.x

- Sander, S., Strizzi, J. M., Cipric, A., Øverup, C. S., & Hald, G. M. (2024). The efficacy of digital help for the broken-hearted: Cooperation after Divorce (CAD) and sick days. Contemporary Family Therapy. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10591-023-09692-7

- Sayehmiri, K., Kareem, K. I., Abdi, K., Dalvand, S., & Gheshlagh, R. G. (2020). The relationship between personality traits and marital satisfaction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychology, 8(1), 15–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-020-0383-z

- Shiota, M. N., & Levenson, R. W. (2007). Birds of a feather don’t always fly farthest: Similarity in Big Five personality predicts more negative marital satisfaction trajectories in long-term marriages. Psychology and Aging, 22(4), 666–675. https://doi.org/10.1037/0882-7974.22.4.666

- Skovdahl-Hansen, H., Mortensen, E. L., & Scioetz, H. (2004). Dokumentation for den danske udgave af NEO PI-R og NEO PI-R Kort Version. Dansk Psykologisk Forlag. Ref Type: Report.

- Solomon, B. C., & Jackson, J. J. (2014). Why do personality traits predict divorce? Multiple pathways through satisfaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 106(6), 978–996. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036190

- Specht, J., Egloff, B., & Schmukle, S. C. (2011). Stability and change of personality across the life course: The impact of age and major life events on mean-level and rank-order stability of the Big Five. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101(4), 862–882. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024950

- Strizzi, J. M., Sander, S., Ciprić, A., & Hald, G. M. (2020). “I Had Not Seen Star Wars” and other motives for divorce in Denmark. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 46(1), 57–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2019.1641871

- Strizzi, J. M., Koert, E., Øverup, C. S., Ciprić, A., Sander, S., Lange, T., Schmidt, L., & Hald, G. M. (2022). Examining gender effects in postdivorce adjustment trajectories over the first year after divorce in Denmark. Journal of Family Psychology: JFP: Journal of the Division of Family Psychology of the American Psychological Association (Division 43), 36(2), 268–279. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000901