Abstract

In this grounded theory study the aim was to explore professionals’ experiences of promotion of adolescents’ sexual health, and views on inter-professional collaboration in relation to this subject. Data collection was by five focus group interviews and two pair interviews with professionals working with sexual health promotion in health care and schools. The results showed that professionals were reaching out to young people through competence and trusting relationships along with working on a broader front. In conclusion, professionals need to be knowledgeable about the world of young people, accessible and able to offer adequate support, and improve their inter-professional collaborations.

Introduction

Adolescents today live in a post-traditional society and experience tension between stricter sexual morals and sexual liberation, between gender repression and sexual equality, which could lead to tensions between forming new sexual patterns and conforming to traditional social forms (Johansson, Citation2016). They are exposed through popular culture and media to an array of sexual images and content which makes sex a topic which is more openly discussed today than in previous generations. Internet access opens up for obtaining any information concerning sex and sexuality that they seek (Neff Claster & Lee Blair, 2017). A British study showed that although adolescents prefer informal sources for sexual health information, they also found school based sources, such as a teacher or the school nurse as useful (Whitfield et al., Citation2013). Professionals have an important role to play in helping adolescents acquire specific knowledge, attitudes and skills related to sexuality (World Health Organization [WHO] & Federal Centre for Health Education BZgA, Citation2010).

Sexual health promotion can be defined as “strategies for improving the sexual health of the population by providing individuals, groups and communities with the tools to make informed decisions about their sexual well-being” (Bailey et al., Citation2010, p. 4). A multisectoral approach is seen as advantageous for improving sexual health. This could involve sexual health services together with community-based peer education, from community leaders, school teachers or the media (World Health Organization [WHO], Citation2010).

In Sweden, sexual health promotion is provided by youth clinics and through schools. Youth clinics aim to offer support and treatment to young people concerning both medical and psychosocial questions, along with problems related to sexual and psychological health in a holistic way. Youth clinics offer health promotion and prevention interventions, and collaborate with other health care providers, schools and social services. The team at youth clinics must include at least one midwife, one counselor or psychologist, and a physician (Association for Sweden’s Youth Clinics, Citation2018). All schools in Sweden are obliged to organize student health care to cover medical, psychological, and social well-being along with special educational measures and interventions. Student health care is provided by a team including a school physician, a school nurse, psychologist and a counselor (The National Board of Health and Welfare (Socialstyrelsen), Citation2016). Sexual health promotion needs to be strengthened for some groups whos sexual and reproductive health and rights are often neglected. This includes people with poor socioeconomical conditions, people who have migrated, people with functional disabilities, LBGTQI persons and young people. Sexual health promotion needs further development which can be achieved through systematic evaluations of interventions for sexual and reproductive health and rights and through strengthening collaborations between different arenas (The Public Health Agency in Sweden, Citation2020).

One way for responding to multiple and interconnected health needs in youth is through teamwork and community-based work (Thomée et al., Citation2016). Nurses working to improve adolescent sexual and reproductive health and rights in communities, schools and public health clinics need not only to provide these services independently. This could also be achieved through collaboration in interprofessional health care teams (Santa Maria et al., Citation2017).

Comprehensive, reoccurring, and inclusive sex- and relationship education forms the grounds for the promotion of sexual and reproductive health and rights (The Public Health Agency in Sweden, Citation2020). Research has shown that sex- and relationship education linked with sexual health services can have an impact on young peoples’ knowledge related to sex and sexuality, delay sexual activity, and help reduce the rates of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and pregnancies (Formby et al., Citation2010). However, in the UK Formby et al. (Citation2010) found that classroom education was separated from health services provided in the school, and that school nurses wished to be more involved in sex- and relationship education. This could enable the school nurse to connect what was taught in the classroom to the service provided. The study also showed that interprofessional collaboration needs to be based on shared understandings, policies, and practices (Formby et al., Citation2010). In Sweden, Widmark et al. (Citation2011) found that collaboration could be complex and problematic and that there could be a low level of understanding on each other’s organizations, distrust, unavailability and uncommunicativeness (Widmark et al., Citation2011). In reviewing the literature few studies were found on professionals’ experience of sexual health promotion, including interprofessional collaboration for the promotion of adolescents’ sexual health.

It is of importance that professionals can meet the needs of young people concerning sexual health promotion and rights. Interprofessional collaboration can be beneficial for promoting sexual health in adolescents, however professionals could experience challenges in interprofessional collaboration due the complexity of collaboration and to high workloads. When reviewing the literature there appears to be a gap in knowledge on how professionals experience sexual health promotion and support for adolescents in matters related to sexuality. Although there is a body of literature on interprofessional collaboration, research in the context of the promotion of adolescents’ sexual health is lacking. The aim of the study was to explore professionals’ experience of sexual health promotion, and views on interprofessional collaboration in relation to the promotion of sexual health in adolescents.

Materials and methods

A qualitative design was chosen for the study, using a grounded theory method, in which data was collected through open focus group interviews. A constructivist grounded theory approach according to Charmaz (Citation2014) was chosen. Grounded theories are constructed through involvements and interactions with people, both present and past, perspectives, and research practices.

Participant recruitment and setting

Participants were recruited at schools and youth clinics in the central part of Sweden. The inclusion criteria were school nurses, school counselors, and teachers in high schools, along with midwives and counselors in youth clinics, as these are professionals who work with sexual health promotion targeted toward adolescents. Initially strategic sampling was employed, but as the analysis progressed the sampling transitioned over to theoretical sampling. Oral and written information was provided to the participants, and an information letter about the study sent with an email to the professionals who were identified in the different school settings. The professionals who agreed to participate were asked to sign a consent form in conjunction with the interview. A total of five focus group interviews and two pair interview were carried out. In the focus groups interviews the range was three to seven participants in each group. The sample consisted of 24 professionals in total, included midwives, nurses, school nurses, counselors, and teachers (). One of the focus groups was with professionals from the youth clinic, three focus groups were with professionals from student health, and one focus group was with teachers in an upper compulsory school. Theoretical sampling lead to a pair interview with a counselor and a social educator. In addition, one follow-up interview with two of the participants from the focus group from the youth clinic was carried out. No further participants or focus groups were considered needed in order to reach saturation.

Table 1. Description of the informants.

Data collection

Data collection was obtained through focus group interviews and two pair interview by the first author (BU) who took the part of the moderator together with the last author (KB) who acted as the observer. The moderator conducted the interviews while the observer followed the interviews, observed interactions within the focus group, took notes, and when necessary could aid with follow-up questions. After the focus group and pair interview both authors discussed the interviews and the notes taken to use them for memo writing. The open-ended interview questions focused on how the different professions experience working with sexual health promotion targeted toward adolescents and their views on collaborations with other health professionals. The goal was that the interviews should have the characteristic of a dialogue. The interviews were adapted to the participants’ answers and reflections and follow-up questions. The interviews took place in appropriate rooms in both the youth clinic and in schools and lasted between 41and 64 min and were audio recorded. An additional follow-up interview lasted 21 min. The reason for the follow-up interview was to deepen the understanding of professionals from the youth clinic’s experiences of reaching boys. Contact was made on one occasion with school nurses after the interview by way of email with the purpose of clarifying one of the topics which came up in the focus group interview.

Data analysis

The interviews were transcribed in verbatim, and analyzed simultaneously by a grounded theory method according to Charmaz (Citation2014). Memos were written after each interview with reflections about what was being said and what was going on, along with writing memos throughout the steps in the analysis. This was done to analyze ideas about codes and emerging theory. In the process of analysis new questions or topics arose modifying the interview questions. The analysis began with initial coding in which coding was carried out line by line. In this step codes stayed close to the data and were expressed with words the reflected action. In the focused coding the initial codes were compared and categorized them while looking for codes that are more significant and conceptual. Thereafter, theoretical coding was performed looking at how codes relate to each other and increasing the abstraction of the analysis and to help theorizes the data. In this step, codes were transformed from Swedish into English. The emergent theoretical codes were sorted and resorted and diagraming was used to aid in the theoretical development. The analysis and data collection continued simultaneously until data saturation was reached and no new qualities were found to modify the emergent theoretical codes.

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Regional ethics approval board in Uppsala, dnr 2018/403.

Results

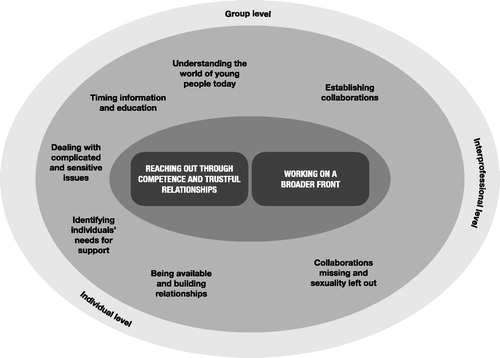

The analysis led to the construction of two main categories: Reaching out through competence and trusting relationships and Working on a broader front. These main categories are comprised of seven subcategories which are in relation to each other. The results can be seen as a process moving from an individual toward a group level along with an interprofessional level, please see .

Figure 1. Professionals reaching out to adolescents through competence and trusting relationships along with working on a broader front.

Reaching out through competence and trusting relationships

The first main category showed that reaching out to young people is considered important for establishing contact, informing about the services at the youth clinic, and to convey that they are available and able to offer support. Understanding the world of young people today is necessary for identifying individual needs of support along with students’ preferences for education. They must consider the timing information and education related to the development and maturity of young people targeted, both on an individual and a group level. Being available and building relationships is seen as a key aspect for gaining trust and giving a sense of security which is important when dealing with complicated and sensitive issues and areas. At the same time professionals find a number of organizational challenges in working with sexual health promotion when working from within an organization, e.g. a school or health care organization.

Understanding the world of young people today

In order to promote sexual health, the importance of understanding the world of young people today was stressed. This knowledge is significant in meeting diversity in young people. In meeting young people, professionals gain insight into their world. They experience young people today as being more open and questioning, and have seen things they themselves have never seen regarding sexuality. It is difficult to imagine the world of young people, and that young people live in a world of their own. This can create a need for young people to be able to talk with someone about these things. Professionals realize that they come from a different generation and at the same time are in a new age and need to develop accordingly with the changes in society. “As a teacher you’re from another generation, and maybe didn’t talk about it when we went to school ourselves, but the youth of today are more outspoken with it comes to getting to know about their body than we were, and ask questions, and maybe it begins as a joke, but ends up as a serious question”. (Focus group (FG) 7, teacher).

It is important to convey to adolescents that on matters related to sexuality there are not always easy answers. Professionals, especially teachers, experience that most adolescents can talk about different sexual orientations without attaching any value to it. In recent years, they have noticed that young people reflect more on themselves, their identity and sexual orientation and are willing and open to talk about it. “When they sit in small groups I have noticed several times that they begin to discuss: ‘What about me? Am I one hundred percent heterosexual?’ And I never heard that ten to fifteen years ago. ‘And can I know?’ No, they are like open in these discussions, ‘No, I am not sure myself’, and then they start to reason”. (FG7, teacher).

Professionals experience that attitudes toward lesbian, bisexual, transsexual, gay and queer (LBTGQI) persons have changed from being very negative, to more open and positive today when young people are more knowledgeable, curious and interested in discussing these topics, even if they can still see in some groups of students that homophobia still exists. Understanding the world of young people today is also significant for meeting diversity in young people. Professionals at the youth clinic experience that young persons who are LBTGQI do not often seek support for their sexual orientation when they have already dealt with it earlier. “I think anyway that coming out as homo or bisexual, it is seldom anyone seeks support because it’s a problem, or needs to talk about it, but when you talk about it, it is like, ya, it’s more like a shrug of the shoulder, that’s the way it is, It’s no big deal”. (FG6, midwife). Non-binary people can seek for physical problems although it could actually be about gender identity issues, for example bodily changes such menstruation. “They wish to be free from bleeding, from menstruation, and when you begin to find out why they want to be free of menstruation and how they experience it, it turns out to be about a question of identity”. (FG5, midwife).

Identifying individual needs for support

It is considered important to identify adolescents’ needs for knowledge and support to be aware of the variety of different needs along with targeting their sexual health promotion work to those with special needs. Midwives and counselors at the youth clinic work to spread information about what they do and what young people can seek help and support with, for example emotional problems. At the same time, they find difficulties in reaching certain groups of young people who may have needs which are not being met, for example school refusal students: “Become of course a group which we don’t reach, those who are not in school. There we try like; the youth clinic is online. That they like anyway can through the Internet get support. But it is of course so that they need to know that we exist. Yes, and then those who don’t seek support have the right to get information”. (FG1, youth clinic). Midwives and counselors at the youth clinic experience that young people with disabilities wonder about the future and reproductivity: They are concerned that staff who work with intellectually challenged young people, and with young people in special living arrangements for mentally and physically disabled may not raise the topic of sexuality and relationships, and therefore not meet their needs in this area. “I have had students who maybe have functional disabilities, and their concerns about the future, children, family, is it even an option? It’s about reproductive health in the longer perspective. And it’s things like that that come to me”. (FG2, school counselor).

One group identified as important to reach are newly arrived foreign students in schools. School nurses and counselors experience that in talking about sexuality and relationships they need to meet the students’ needs and be aware and sensitive to cultural and religious aspects related to sexuality. Stay-at-home students are another group of young people which may have unmet needs related to sexuality. Also, boys can be difficult to reach. While it can be more natural for girls to visit the youth clinic to get contraceptives and pregnancy tests, the professions experience that they may be missing the boys. They experience that boys often turn to those close to them or to the Internet first before seeking professional help, and that boys sometimes have to cross barriers before coming to the youth clinic. When questioning boys, they learned that it is common that it is first when the boys are feeling very bad that they seek help, which they feel contributes to unnecessary suffering. They also experience that boys have difficulties in talking about their emotions and consider that it is important to bring up the topic of masculinity and masculine culture with boys. “Yes, of course, they are out there (boys), who have things that trouble them. They are no different from girls I think. But they don’t have the same training, I believe, in actually talking about it. Because I don’t think that we train them. No, there are no role models for them either, neither in television, films or around them. So, we don’t see either that they go and seek support”. (FG6, midwife, youth clinic). One counselor hoped to engage male teachers in starting a boys-group.

Professionals experience that many young people are vulnerable and see a connection between sexual health and mental health. Young people who have not found their identity yet are at risk for experiencing mental health problems. Vulnerability can be seen in relation to alcohol use and sexual behavior, consenting to having sex, insecurity about relationships, lack of factual knowledge about sex and relationships. Professionals identify the need to provide knowledge and offer support related to these issues. A counselor stated: “Then I think, that you meet young people who have enormous risk behavior, and who’s mental health most likely… then we can establish that what many of these students testify is that they don’t feel good”. Another counselor continued: “Yes, I can easily see a connection (between low self-esteem and risk behavior), even if it isn’t determined. And if you can get access to psychiatric help, then the chance that you don’t put yourself at risk sexually, that you won’t be crossing boundaries in a destructive way”. (FG5, school counselors). Talking about sexuality can be important for promoting mental health considering the connections between the well-being of young people, self-esteem and sexual risk behavior.

Timing information and education

When working with promoting sexual health professionals realize the importance of timing in order to tailor to the age-appropriate needs of young people. Timing information and education entails assessing the right time to meet a class, considering prior knowledge, maturity and experience. They consider it important to begin early to talk about sexuality and relationships, already in primary school, and continue in different grades, adapting and adding new topics in relation to the development and maturity of the students. A school nurse explained that because of the wide range in the onset of puberty, sexual health promotion should build upon this. Professionals experience that what students’ questions change with increasing age and boys seek for information when they are older and more mature. Within the same grade there is a variation in students’ maturity which poses a challenge when teaching about sexuality and relationships. One teacher gave an example about day after pills: “Half the class doesn’t even know what the day after pill is. So, they are on different levels. But just that knowledge can give me an insight. It is like an example of something that I need to be a part of because that is the reality”. (FG7, teacher).

Being available and building relationships

Some key aspects were experienced as being beneficial when working with young people, such as being available and building relationships. It is also entailing seizing opportunities when they arise. Building relationships with young people aids in creating a sense of security and trust. “It’s when you get to know them, when they feel secure, then the conversations will become deeper”. (FG3, school nurse). Availability can be achieved in a number of ways, such as promoting the online website and meeting individuals and groups through community outreach. This can result in more visits from boys at the youth clinic. The school is considered to be the most important arena, with incredible possibilities for health promotion in a young person’s life, for example starting girls-groups and boys-groups.

Professionals exhibit their availability by keeping an open door, attend to all the young people that come to them and provide the opportunity to talk with an adult.

I have many students that just come in to weigh and measure themselves, or whatever it is about, and then you create of course a relationship which is actually very important. And we are ahead everyone else thanks to our health talks. I am convinced about it, that the reason we have so many students coming to us compared to other professionals, it that we meet each and every one. (FG3, school nurse)

One way to reach young people is to seize opportunities when they arise. When a student comes to the school nurse for contraceptives, this can be used as an opening to ask more questions and to talk about sexual health. Using the curiosity of students about sexuality was also identified by the school nurses as an opportunity to talk with them about sexual health. School nurses give an example: “But otherwise it is, just as (one of the school nurses in the focus group) also says, there is a lot of this, emergency day after pills and what not. Then you automatically have a talk about that”. And another school nurse fills in: “So, then you have the opportunity to ask, when the come and want these pills, then you get an opening, and can ask how they feel”. (FG3, school nurse).

Professionals encounter a number of challenges for being available and building relationships, both within the school organization and in the health care organization. This includes lack of time and recourses, the leadership of the organization not prioritizing sexuality and relationship education, and gaining access to students. Teachers experience a lack of time to manage all their teaching duties concerning sexuality and take notice that according to the new time schedule, time should be allowed for discussions about health and sexuality. “It’s going to be tougher times. We will have to reduce science classes. If I am going to cut something out of biology class it’s not going to be sex education, I’d rather take something else out” (FG7, teacher). They consider that in the best of worlds, sexuality and relationship education should be integrated into several subjects. They also experience that sexuality and relationship education is not prioritized by the school leaders even though research and reports find that students are not receiving sufficient education in the subject. Despite budget cuts, teachers are unwilling to decrease the amount of time spent teaching sexuality and relationship education.

Counselors and school nurses experience difficulties in gaining access to students in sexuality and relationship education due to strict time plans, “Often in the school world, when it comes to people like us, the expression is schedule-disrupting activities, seriously! The principal stands there and says, these kinds of schedule-disrupting activities we can’t do”. (FG2, counselor). When not being invited by teachers, school nurses together with counselors could take the initiative to start their own projects with groups of students to promote mental health along with sexual health. Issues being brought up in individual counseling can now be addressed on a group level. Factors seen as enabling for project work include students feeling secure with each other and creating an open atmosphere which facilitates discussions. Drawing on your own experiences when talking about communication and having other speakers to participate was also found to be facilitating. Some positive outcomes from the project work were seen, such as catching the interest of teachers who in turn wanted to become involved in developing the project.

Dealing with complicated and sensitive issues and areas

Professionals experience when meeting individual young people, that they can encounter very complicated and sensitive issues to deal with when it comes to sexual health. They need to use their own abilities, qualities and professional competency; therefore, they consider the necessity for developing their competence.

Complicated and sensitive issues many young people seek support for can be related to close relationships, or with questions about identity or sexual orientation. Often, they seek support when something becomes problematic. They experience that young people do not often seek support from their parents when it comes to sensitive questions about sexual health. “It is a subject which is very sensitive and important for our teenagers. At the same time, it’s private, and it is something that you perhaps don’t want to bring up with your parents”. (FG2, counselor). They experience that it is easier for young people to talk about things of a physical nature, and sometimes they start there before actually bringing up what they really want to talk about. Other times, the question can be woven into the conversation. Another counselor experienced: “Often, when it is about, what should we say, sexual health or so. I believe that we begin to talk about it if I suspect something, and perhaps ask a few questions, and then get closer and closer. Sometimes they can just blurt it out, but often it is concealed in a longer conversation. So, it gets brought up, for the most part”. (FG4, counselor).

In dealing with complicated and sensitive issues, using yourself as a means is something experienced as facilitating. Self-realization, such as being aware of your own sexuality in order to feel secure in meeting young peoples’ sexuality, and confronting your own prejudices and preconceived ideas provides confidence. Teachers find it difficult at times to answer questions when there is not always enough knowledge and research on topics related to sexuality due to the rapid changes in society. “when I worked in a different county I had in-service training (about sex education) at least once a year. Since I came here 12 years ago, I haven’t been, or maybe once”. (FG7, teacher). Another stated “you read the newspaper and read some research, when you teach you need to update yourself”. (FG7, teacher).

Professionals consider it important to show respect, be able and willing to listen to what young people say, and avoid being heteronormative. They consider it important to learn to understand students in order to find out the best way to handle the subject area and meet the student on their own grounds. They must not avoid questions, but dare to ask, naming and talking about topics concerning sexuality. “Then I haven’t understood or asked the right questions. Because I ask questions, but ask them as openly as possible so that they feel like I don’t need to answer this if I don’t want to, or so. Then I really try not to pressure a student, but at the same time show respect and that I am capable of taking it, that it’s okay”. (FG5, counselor).

School nurses and counselors are committed to working with young people coming from different backgrounds along with their parents. When school nurses and counselors are involved in classes for newly arrived foreign students in Sweden, they experience that it is important to build up a relationship with the students and then wait and listen for questions to arise. They are aware of the importance to listen to the young person and not try to inflict their own thoughts of values on them.

It’s brought up extremely discretely, like very hesitantly. If I should encourage the student to make their own decisions, make their own choice. ‘You know that this is you and your body and it is you who decide over your life’, like that. What does that mean in relation to the family then? So, I feel that I have to be very careful like what I say, like just listen to this person, empower this person in their own thought and not in any way try to affect, or put any of my thought and values into it, just empower their own (thoughts). (FG5, social educator)

Developing competence was also considered to be of importance in dealing with complicated and sensitive issues/areas. They experience a need for further education, to replenish and update knowledge about sexuality and identified different alternatives. Teachers experienced midwives as an important source of information on new phenomenon, new terminology related to sexuality, and to learn how they work with sexual health at the youth clinic.

It was considered important that sexual health promotion should be brought into the regular curriculum in schools, and not be just a one-time effort. They realize the complexity of the subject, that many topics are related to each other and in turn can affect sexual health. They mean that the school leaders are responsible for sexuality and relationship education in schools and play an important role to ensure further education, coordinating and allowing time for working with the subject. They identify leadership in schools as being important and mean that leaders/principals should be the front figures in conveying the importance of working with sexual health promotion. “It has to do with leadership, that the school leaders should tell us that (sexual health) should be part of our education in school. The leaders should take the lead and show us that this is an important issue”. (FG4, school counselor).

Working on a broader front

The second main category showed that collaboration is seen primarily as a means to reach adolescents and being able to meet their needs, and as a way to succeed with sexual health promotion. They are not only working within their own organizations, but also working on a broader front establishing collaborations. Midwives and counselors in the youth clinic identify actors with whom they are missing collaborations, and experience that other health care providers are leaving out sexuality when caring for young people.

Collaboration missing and sexuality being left out

Collaboration is considered as giving and taking, creating involvement, and that networks are good for exchanging experience and knowledge. “how you can in practice make it work, that is to keep the question alive somehow. Then network meetings where you can exchange experience and knowledge can be very good¨. (FG4, school counselor). Collaboration is seen as beneficial for planning how to work with sexual health promotion and for keeping issues alive and ongoing. Collaboration enables them to reach young people who may not otherwise come to talk about their concerns. Collaboration in education can create an opening for seeking help and guidance from the youth clinic, along with directing them to other health care providers outside the school organization for support. Professionals realized the need to do more to improve and strengthen their work with sexual health promotion. Integrating new knowledge from both authorities and through interactions with young people helped to expand new perspectives which could be incorporated in sexual health promotion.

Establishing collaborations

Collaborations are actively being established. The different professional groups in this study; school nurses, school counselors and teachers working with sexuality and relationship education in schools, along with nurses, midwives and counselors at the youth clinic, more or less collaborate with each other. “(collaboration) could be further developed I think. I know several counselors who work at the youth clinic. Then I feel that it’s easy to turn to them when you have a relation to someone there, or knowledge about the person. Meeting them here made it much easier”. (FG4, school nurse). School nurses and counselors participate in a regional network for sexual and reproductive health rights where they receive current information about sexual health. Other actors who professionals have established collaborations with include social services, police, child habilitation, along with organizations such as an organization for transgender persons. Professionals can meet with a student on a regular basis and offer support over a longer period of time, while being aware that some complex situations are sometimes better handled by other health care providers.

It is considered valuable to include the school nurse in sexuality and relationship education. One school counselor stated: “It’s (school nurses) that meet the students on a daily basis, they who have a relationship with the students and meet them all the time. That’s when I think the you have a chance to be able to influence. It’s difficult to influence a person if you don’t have a relationship with him/her, in some way”. They experience that the school nurse knows more about the students’ world, and can tell the teachers about that, giving the teachers insight into a world they do not know so much about.

Working closely together is beneficial for teamwork and they experience the importance of physical proximity to each other. This means having an open door, being open and accepting with each other, making decisions together, being able to ask questions of each other and admit shortcomings, along with coaching and supporting each other and when having offices next to each other. “And dare to ask and dare to confess your flaws. We mentor each other. When you get a heavy case then you go in through a door which feels secure, and so ‘what would you have done here?’. But I feel that, if it is something came to me where I think, this is something where it would be good with a contact with a counselor, then it is like, go to a counselor’s door and like talk” (FG1, midwife, youth clinic). When working in project groups professionals consider the composition of the group as being of importance for collaboration, and find strength in being a group.

When organizing collaborations, professionals from the youth clinic experience that it is important to find a key person. They see the school nurse as a key person who can coordinate visits, however it can sometimes be difficult to identify who he/she is. They experience that they must relate to many people in their work and that personal contacts and having a relationship to someone working there makes collaborations much easier. One counselor stated: “It is also a way to make the path shorter like, between those who work, and knowing who has different functions or that you can quickly get a hold of a person or exchange phone numbers, or whatever else it could be, to be able to help. So that is good”. And another counselor filled in: “No, it could probably be developed more I think. I know several… counselors in any case, who work at the youth clinic here. Then I feel that it is a short path and it’s easy when you have a relationship to someone, and yes, knowledge about a person”. (FG4, counselor).

Collaborations missing and sexuality being left out

While professionals are actively establishing collaborations, they experience that there are some collaborations missing. Midwives and counselors from the youth clinic are missing collaborations with some arenas which could be beneficial for reaching specific groups of young people. They experience that they are dependent on others for collaboration and that collaboration is often dependent on enthusiasts and who is in charge, such as school leaders or leaders of the student body. “No, but the problem is that some are dedicated to this. Then when there are enthusiasts, then it goes smoother and they get others to join in. They rely on their enthusiasts, and when they disappear, then it all falls apart. So that it is very dependent on the person”. (FG1, midwife, youth clinic). Midwives and counselors from the youth clinic find it more difficult to collaborate with principals than teachers, and that principals have a lack of knowledge about the youth clinic.

When considering partners for collaboration, they consider schools as being most important, however, collaboration is very dependent on the contact person from the school. They also realize that they must go through the adults in school to reach the young people. This also goes for school nurses and school counselors, needing to go through the teachers to gain access to the class, not always succeeding. They experience that it is up to them to be the ones to take initiative and be the driving force in collaborations. “Collaboration is a primarily a means for reaching young people. We are seldomly asked to come out to high schools. It’s we who say that we are coming to you, when can we come? It feels as though nothing would happen, that it is up to us to contact them”. (FG1, midwife).

Professionals experience the main hindrances for collaborations are lack of time and resources. They experience both a lack of their own time and the time others have for collaboration, along with getting the lecture time to meet the students. Professionals also experience organizational challenges, such being governed by time plans. Sexuality and relationship education should follow national guidelines which states that the education should be integrated into several subjects. In collaboration between the different organizations, e.g. schools and the youth clinic, they realize the need to work out the logistics of and forms for the collaborations. Lack of resources in the youth clinic posed an obtacle for working with outreach, meeting demands and availability to meet with a counselor at the youth clinic. Midwives and counselors at the youth clinic expressed that they would be out more if they had the resources for it. “The youth clinic doesn’t have the resources. What do you do if you only have two to four hours a week (for outreach work)”. (FG1, midwife).

One great cause of frustration for professionals was realizing that other health care providers were not addressing the issue of sexuality when meeting young people in different health care settings. They mean that other actors should be doing their part in addressing these issues. They experienced that sexuality was being left out by other health care providers and are frustrated when sexual health is not seen as influencing mental health. They believe that getting appropriate psychological support can also help to reduce sexual risk-taking. One midwife told about a young person who had seen another health care provider who had not brought up the topic of sexuality and then came to the youth clinic: “Sexual and reproductive health had perhaps not been a top priority. We asked questions about sexuality and identity and the person’s thoughts about gender. And it was a trans person. Now it came up on the first meeting. And the depression was grounded a lot in that, but the young person was afraid to bring it up”. (FG1, midwife, youth clinic).

A number of reasons for sexuality being left out by other actors, as lack of knowledge, discomfort or fear in talking about it, or for cultural reasons were considered. Health care professionals in other settings can avoid these issues by hiding behind their own professional fields and focus of work. The professionals in the study mean that more education about sexual and reproductive health issues for all who work with humans is needed because health care personnel lacking in education lack the recourses and tools to address issues concerning sexuality. They strongly believe that sexual health should be part of the education for all health care workers. “Questions about sexual and reproductive health, should be included in educations, and it is more today, but, it should like be for all who work with people I meant to say. And in the education, in nursing education, midwife education, in teacher educations, yes, in all educations for working with people. I am thinking physiotherapists. Yes, those who you meet in health care, where sexuality isn’t included”. (FG1, midwife, youth clinic).

Discussion

Sexual health promotion is a public health challenge. The results showed that in reaching out to adolescents there is a need for understanding the world of young people today, in order to promote sexual and reproductive health and rights and that this knowledge is significant in meeting diversity in adolescents. A report from the Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention from 2018 showed that nearly one fifth of all young people age 16–24 have experienced criminal offenses in close couple relationships. This includes physical abuse, sexual crimes, threats, and harassment (Axell, Citation2018). A Swedish study on sex and the Internet among high school students showed that one fourth of the students sent nude photos to someone else or posted them on the internet, so called sexting. Also, 5,7% of the students met someone on the internet during the past twelve months with whom they had sex with. Nearly one fifth of the students reported having been contacted by someone at least five years older than them for sexual purposes or grooming, i.e. being asked to talk about sex or pose in sexual contexts (Svedin et al., Citation2015). Media have also recently reported a new phenomenon where popular influencers tell young people about the possibility of earning money by starting private accounts for posting naked and pornographic content on a website. These are all examples of the world in which young people live today. Therefore, health professionals need to follow the debate in the media and be curious and ask quesions in order to obtain first hand information from adolescents seeking support.

Professionals in the current study identified groups of adolescents which they found difficult to reach and who they consider may have unmet needs related to sexuality. This included many boys, but also intellectually challenged or adolescents in special living arrangements for mentally and physically disabled, school refusal students/absenteeism. Professionals experienced that many boys have difficulties in talking about their emotions and therefore consider that it is important to bring up the topic of masculinity and masculine culture with boys. Claussen (Citation2019) stressed the importance of developing a curriculum for sexual health education that enables a dialogue with young men for critically engaging and reflecting on the relationship between gender ideologies and their own developing understanding of masculinity and sexuality. In the current study, professionals from the youth clinic believed that having more men in the team would aid in reaching young men. However, another study from Australia found that although a majority of young men stressed the importance of having male staff members, it was also stated that not everyone might prefer a male practitioner, what was most important was being provided the choice regarding the gender of the practitioner (Rice et al., Citation2018). This is something which should be taken into consideration when staffing health services.

That it is common for young people with disabilities to have unmet needs related to sexuality is confirmed by Campbell et al. (Citation2020). They found that young people with disabilities were often excluded from formal sex education programs due to the presumption that they unable to comprehend the complexity of sexual relationships. This leads to young people with disabilities being forced to navigate their sexual experience with little or no support. This also highlights the great need for reaching these young people who are often left out. Sexual health needs in young people must be recognized in all areas of health care. Consequently, it is important to ensure that sexual health is included in the education of all health care professionals.

Another finding in the study was that professionals experienced that sexuality was left out by other health care providers when meeting with adolescents. A number of reasons for sexuality being left out by other actors were mentioned in the results, such as lack of knowledge, discomfort or fear in talking about it, or for cultural reasons were considered. This is corroborated by a systematic review on nurses providing sexual health education in health care settings which showed that sexual health care information was not widely being addressed. Factors involved were lack of knowledge about sexual health, attitudes and beliefs from nurses that it is something private and not a priority, nurse’ discomfort in talking about sexual health, and perceived barriers related to time, responsibility and organizational support (Fennell and Grant 2019).

Professionals in the current study believed that health care professionals in other settings could avoid these issues by hiding behind their own professional fields and focus of work. Research has shown (Fennell & Grant, Citation2019), that in other areas of health care, a perceived barrier to delivering sexual health information to patients was when nurses questioned how sexual health was part of their scope of practice. Nurses also experienced a lack of policies about the role of nurses in discussing sexual health with patients along with organizational support needed for allowing time for nurses to address these issues. This could be interpreted as sexuality being an unimportant area in nursing. Traumer et al. (Citation2019) found that patients experienced that sexuality is a sensitive and taboo subject in health care and when bringing up the topic their initiatives were dismissed by health care professionals. Higgins et al. (Citation2006) meant that if nurses do not introduce the topic of sexuality with patients, they will not be able to assess if there are any specific needs in this area, which could lead to patients left struggling alone with unanswered questions and concerns.

Professionals experienced a number of organizational challenges in working with sexual health promotion when working from within an organization, e.g. a school or health care organization. A Swedish study (Thomée et al., Citation2016) showed that there were organizational challenges for youth clinics, including weak clear directives and leadership, heavy workload and an unequitable distribution of resources, which is in line with the results of the current study. Formby et al. (Citation2010) found that classroom education was separated from school nurses’ health services provided in the school. Formal and informal collaboration between teachers and school nurses would be beneficial for promoting sexual health. Borup (Citation2002) showed that school nurses are dependent on collaboration with the teachers and other professions within and outside of school. This collaboration needs to be built on mutual interests, knowledge about each other’s professions along with strengths and barriers to form a mutual respect, necessary for collaborative work (Borup, Citation2002).

The results showed that collaboration was seen primarily as a means to reach adolescents to meet their needs, and as a way to succeed with sexual health promotion. Professionals worked on a broader front by establishing collaborations with other actors. Professionals McCarty-Caplan and MacLaren (Citation2019) in a study from USA, meant that with limited resources there is a potential for benefits of interdisciplinary collaboration between professionals that share goals in meeting the needs of young people (McCarty-Caplan & MacLaren, Citation2019). An advantage of interprofessional collaboration, found in a Canadian study, can be that one professional can report to another professional about a patients’ condition and need for intervention, which without collaboration may have been missed or ignored (Zwarenstein & Reeves, Citation2006). The full potential for interprofessional collaboration does not seem to be realized by the professionals in the current study in a Swedish context. A better understanding of each other’s professions, what they can contribute with and their limitations could enhance their mutual efforts in promoting sexual health in young people. Widmark et al. (Citation2011) investigated barriers to collaboration between health care, social services and schools. Unsuccessful collaboration was marked by unclear allocation of responsibility, lack of resources, knowledge and feedback, disbelief in others competence, lack of commitment, unrealistic expectations, boundary crossing, and territorial thinking. In the current study, limited time and resources were often mentioned as a hinderance in collaboration. The need for resources should be addressed in the organization, while health professionals also need to realize the benefits of interprofessional collaboration. This is supported by Suter et al. (Citation2009) who showed that health care providers found it important to have an environment which is supportive of collaborative practice and the development of collaborative competencies. This includes the provision of time, resources and encouragement to engage in collaborative practice.

In the results, teamwork between professionals within their organizations was reported as being good, however collaboration between professionals from different organizations was sometimes seen as difficult and was not formally organized. Research from USA and Canada shows that competencies related to collaboration with interprofessional team members include shared goals (Cappiello et al., Citation2016), understanding and appreciating professional roles and responsibilities and communicating effectively (Cappiello et al., Citation2016; Suter et al., Citation2009) along with providing referrals to other resources or specialists in sexual and reproductive health care when appropriate (Cappiello et al., Citation2016). The motivation for interprofessional work comes from the realization that each discipline on its own is not able to meet all the patients’ needs (Suter et al., Citation2009). Interprofessional collaboration is complex which can explain why professional in the study experienced difficulties, especially in collaborations with other organizations, even though they shared the same goals for sexual health promotion in young people. In Sweden, nursing competency includes collaboration in teams. This entails initiating, prioritizing, coordinating and evaluating team work on the grounds of the patients’ needs and resources. It also involves planning, consulting and collaborating with other actors to ensure continuity in the chain of care (Quality and Safety Education for Nurses Institute, Citation2020). The results show that there a need for improvement in interprofessional collaboration.

Methodological considerations

The use of focus group interviews was judged to be a suitable method for the study. The method can be especially suitable when actions of people and their motivation for action are being studied (Krueger, Citation2014; Wibeck, Citation2010). Although individual interviews are the most common method for data collection in Grounded Theory studies, focus group interviews could also be an appropriate method when Grounded theory has theoretical underlying in symbolic interactions. Charmaz (Citation2014) explains that in symbolic interactionism human actions are viewed as constructing self, situation, and society, and in which language and symbols are a part of forming and sharing meanings and actions (Charmaz, Citation2014). Focus group interviews have been used in constructivist grounded theory research (Elliott et al., Citation2019; Ryan, Citation2014; Straughair, Citation2019). Two pair interviews were included. The reason for including one of the pair interviews was because it was seen as important to include school counselors from another high school to gain more in-depth data, which is in accordance with theoretical sampling in grounded theory research. The other pair interview was a follow up interview with two participants from the youth clinic. According to Charmaz (Citation2014), in grounded theory, data collection methods flow from the research questions. Interviewing is used to advance the process in constructing theory. In moving forward it is sometimes of value to return to participants to ask a further question in order to get at deeper view (Charmaz, Citation2014). Saturation was reached when no new qualities of the pattern were found in the theoretical categories.

Charmaz (Citation2014) proposes the criteria credibility, originality, resonance, and usefulness for evaluating studies using grounded theory and means that the combination of credibility and originality help to enhance resonance, usefulness and the subsequent value that the theory contributes to knowledge (Charmaz, Citation2014). In the study, credibility was achieved by gaining a deeper understanding of the subject being studied. The data collected was rich and sufficiently ample for constructing a theory Coding was conducted by the first author and then discussed and modified with the other two authors. Constant comparisons between the data and the categories assures that the links are logical and the categories are grounded in the data. Originality could be seen as offering some new insights when there are few previous studies in this context. Resonance in the study is reflected by the rich content in the categories. There are links in the results between individual young people, specific groups of young people and professionals, and between different professions. The results also show links from individual levels to group and organizational levels. Usefulness of the results could be to contribute with identifying adolescents’ needs for support along with providing arguments for increasing support and recourses for sexual health promotion.

A limitation in the study was that there were only three men who participated. This reflected however on the number of men who work in the professions included in the sampling. Other perspectives and experiences might have been found if more men were included. Another limitation could be in limited transferability of the results while this study was conducted in a Swedish context. Sweden has a well-developed organization of youth clinics, a long history of sex- and relationship education in schools, and holds liberal views on sexuality in society, which may not be the case in many other countries.

Conclusion

The results indicate that professionals need to be knowledgeable about changes in society. They also must be accessible and able to offer adequate support on these issues along with conveying to young people that they are understanding, able and willing to talk about sensitive issues. Male professionals are needed, not only in sexuality and relationship education but also in health care services. The need is great for more male school nurses and nurses in youth clinics where young men can meet adult men who can act as role models, and address norms on masculinity and sexuality with young men. Problems related to sexual health could have a direct impact on mental health, therefore it is of the utmost importance that health care professionals ask these questions related to sexual and reproductive health and rights when meeting adolescents. Sexuality and sexual health should be included in the curriculum for health care educations, providing the skills and knowledge needed for health care professionals can aid in feeling more comfortable in bringing up the topic with young people. A better understanding of the potential of interprofessional collaboration for promoting sexual and reproductive health and rights could increase motivation for pursuing collaborations, while the need for resources to allow more time to work with collaborations should be addressed in the organization.

Conflict of interest statement

A declaration of interest statement has been added.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Association for Sweden’s Youth Clinics. (2018). Ungdomsmottagningen i första linjen för psykisk ohälsa [The youth clinic in the front line for mental health]. Förening för Sveriges Ungdomsmottagningar.

- Axell, S. (2018). Brott i nära relationer bland unga [Crime in close relationships among youth]. https://www.bra.se/download/18.c4ecee2162e20d258c4a9ea/1553612799682/2018_Brott_i_nara_relationer_bland_unga.pdf

- Bailey, J. V., Murray, E., Rait, G., Mercer, C. H., Morris, R. W., Peacock, R., Cassell, J., Nazareth, I. (2010). Interactive computer‐based interventions for sexual health promotion. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (9), 1-68. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006483.pub2.

- Borup, I. K. (2002). The school health nurse’s assessment of a successful health dialogue. Health & Social Care in the Community, 10(1), 10–19. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.0966-0410.2001.00337.x

- Campbell, M., Löfgren-Mårtenson, C., & Martino, A. S. (2020). Cripping. Sex Education, 20(4), 361–365. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2020.1749470

- Cappiello, J., Levi, A., & Nothnagle, M. (2016). Core competencies in sexual and reproductive health for the interprofessional primary care team. Contraception, 93(5), 438–445. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2015.12.013

- Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory. SAGE.

- Claussen, C. (2019). Men engaging boys in healthy masculinity through school-based sexual health education. Sex Education, 19(2), 115–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2018.1506914

- Elliott, S., Bevan, N., & Litchfield, C. (2019). Parents, girls’ and Australian football: A constructivist grounded theory for attracting and retaining participation. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 12(3), 1–22.

- Fennell, R., & Grant, B. (2019). Discussing sexuality in health care: A systematic review. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 28(17–18), 3065–3076. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.14900

- Formby, E., Hirst, J., Owen, J., Hayter, M., Stapleton, H. (2010). Selling it as a holistic health provision and not just about condoms …’ Sexual health services in school settings: Current models and their relationship with sex and relationships education policy and provision. Sex Education, 10(4), 423–435. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2010.515099

- Higgins, A., Barker, P., & Begley, C. M. (2006). Sexuality: The challenge to espoused holistic care. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 12(6), 345–351. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-172X.2006.00593.x

- Johansson, T. (2016). The transformation of sexuality: Gender and identity in contemporary youth culture. Routledge.

- Krueger, R. A. (2014). Focus groups: A practical guide for applied research. SAGE.

- McCarty-Caplan, D. M., & MacLaren, S. (2019). School social work and sex education: Expanding school-based partnerships to better realize professional objectives. Children & Schools, 41(3), 141–151.

- Neff Claster, P., & Lee Blair, S. (2017). Gender, sex, and sexuality among contemporary youth: Generation sex. Emerald Publishing Limited.

- Quality and Safety Education for Nurses Institute. (2020). QSEN institute competencies. https://qsen.org/competencies/pre-licensure-ksas/#teamwork_collaboration

- Rice, S. M., Telford, N. R., Rickwood, D. J., & Parker, A. G. (2018). Young men’s access to community-based mental health care: Qualitative analysis of barriers and facilitators. Journal of Mental Health, 27(1), 59–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2016.1276528

- Ryan, J. (2014). Uncovering the hidden voice: Can grounded theory capture the views of a minority group? Qualitative Research, 14(5), 549–566. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794112473494

- Santa Maria, D., Guilamo-Ramos, V., Jemmott, L., Derouin, A., & Villarruel, A. (2017). Nurses on the front lines. American Journal of Nursing, 117(1), 42–51. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NAJ.0000511566.12446.45

- Straughair, C. (2019). Cultivating compassion in nursing: A grounded theory study to explore the perceptions of individuals who have experienced nursing care as patients. Nurse Education in Practice, 35, 98–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2019.02.002

- Suter, E., Arndt, J., Arthur, N., Parboosingh, J., Taylor, E., & Deutschlander, S. (2009). Role understanding and effective communication as core competencies for collaborative practice. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 23(1), 41–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820802338579

- Svedin, C. G., Priebe, G., Wadsby, M., Jonsson, L., & Fredlund, C. (2015). Unga sex och Internet–i en föränderlig värld [Youth, sex and the Internet - in a changing world]. Linköping University Electronic Press.

- The National Board of Health and Welfare (Socialstyrelsen). (2016). Vägledning för elevhälsan. https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/globalassets/sharepoint-dokument/artikelkatalog/vagledning/2016-11-4.pdf

- The Public Health Agency in Sweden. (2020). Nationell strategi för sexuell och reproduktiv hälsa och rättigheter [The National Strategy for Sexual and Reproductive Health and RIghts]. https://www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se/contentassets/0d489b0821164e949c03e6e2a3a7e6cc/nationell-strategi-sexuell-reproduktiv-halsa-rattigheter.pdf

- Thomée, S., Malm, D., Christianson, M., Hurtig, A.-K., Wiklund, M., Waenerlund, A.-K., & Goicolea, I. (2016). Challenges and strategies for sustaining youth-friendly health services — A qualitative study from the perspective of professionals at youth clinics in northern Sweden. Reproductive Health, 13(1), 147. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-016-0261-6

- Traumer, L., Jacobsen, M. H., & Laursen, B. S. (2019). Patients’ experiences of sexuality as a taboo subject in the Danish healthcare system: A qualitative interview study. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 33(1), 57–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.12600

- Whitfield, C., Jomeen, J., Hayter, M., & Gardiner, E. (2013). Sexual health information seeking: A survey of adolescent practices. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 22(23–24), 3259–3269. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.12192

- Wibeck, V. (2010). Fokusgrupper: Om fokuserade gruppintervjuer som undersökningsmetod (2nd ed.). Studentlitteratur.

- Widmark, C., Sandahl, C., Piuva, K., & Bergman, D. (2011). Barriers to collaboration between health care, social services and schools. International Journal of Integrated Care, 11(3), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.5334/ijic.653

- World Health Organization [WHO]. (2010). Developing sexual health programmes: A framework for action. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/70501/WHO_RHR_HRP_10.22_eng.pdf;jsessionid=FC4081670EE72F70C4EA1B8ABF84E7E6?sequence=1

- World Health Organization [WHO] & Federal Centre for Health Education BZgA. (2010). Standards for sexuality education in Europe: A framework for policy makers, educational and health authorities and specialists. https://www.bzga-whocc.de/fileadmin/user_upload/WHO_BZgA_Standards_English.pdf

- Zwarenstein, M., & Reeves, S. (2006). Knowledge translation and interprofessional collaboration: Where the rubber of evidence‐based care hits the road of teamwork. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, 26(1), 46–54. https://doi.org/10.1002/chp.50