ABSTRACT

The main purpose of this study is to explore the projected destination image represented by photographs emerging in social media from a potential DMO member. The official page of China Eastern Airlines on Facebook (@CEAir) was selected as a case study, in which a total of 40 photographs were collected and classified into five groups according to their themes. To identify the destination image of China, five groups of photographs were analyzed by using visual analysis, semiotic analysis, and multimodal discourse analysis. The main findings show that Chinese food, architecture, natural landscape, people, and ethnic minorities are common signs engaging in constructing the destination image of China. These photographs mainly adopted wide shots and brilliant color tones, which convey to overseas tourists that China is a great power with a long history, full of charm, and a contributor to global development. More importantly, not only landscape photography but also still life photography, candid photography, and travel photography are all considered to be modes of representation of the destination image. Different genres of photography employ Chinese culture as a special gaze to shape the destination image.

摘要

本研究的主要目的是探讨潜在的旅游目的地营销管理组织在社交媒体平台以照片形式投射的目的地形象。本文以中国东方航空公司为案例,以其发表在脸书社交平台上(@CEAir)的宣传照片为研究样本。研究共收集40张摄影照片,并根据照片的主题分为5组,使用视觉分析、符号学分析以及多模态话语分析进行分析从而总结出中国的投射目的地形象。结果表明中国传统美食、建筑、自然景观、企业员工和少数民族风情是中国东方航空投射中国目的地形象时使用的常见符号。摄影手法主要采用大景别与亮色调,向海外游客投射出中国是一个历史悠久、充满魅力的大国,同时中国也是全球发展的贡献者。更重要的是,研究结果表明除了景观摄影之外,静物摄影、抓拍摄影和旅行摄影都被认为是目的地形象的表征模式。不同的摄影流派将中国传统文化作为一种特殊的‘凝视’目光去塑造旅游目的地形象。

1. Introduction

A compelling tourism destination image plays a significant role in influencing tourists’ engagement, buying decisions, destination choices (Gasawneh & Adamat, Citation2020), and satisfaction (Pan et al., Citation2021). It also enhances the competitiveness of tourism organizations (Xiao et al., Citation2020). Photography has always been closely connected to tourism, being considered an indispensable tourism activity both for tourists and tourism organizations (Aquino, Citation2016; Xiao et al., Citation2020). Therefore, this paper aims to explore the ways in which a destination image is represented by photography.

Historically, photography was a medium that was used to present places from the colonial era; when photography was first invented, it was quickly absorbed into documentary surveying (Edwards, Citation2011). In the 1840s, during the First Opium War, soldiers, diplomats, and merchants sought to satisfy the curiosity of their homelands by photographing what they saw for geopolitical ambitions and trade purposes (Roberts, Citation2013). Since then, the people and lifestyle of China have been exposed to the world through photography (Roberts, Citation2013, p. 7). Photography has also been an important medium for propaganda in China from the perspective of military, politics, local life, and culture.

The 19th and 20th centuries saw the advancement of worldwide social transformations and changes to urban life, which promoted people’s participation in the field of photography and led to the emergence of amateur photography (Aquino, Citation2016). With the implementation of the most important advertising campaign, ‘Kodak moment,’ photography as a medium to record and represent places has been highlighted by the photographic practices of tourists. This photographic practice became tourists’ particular ‘way of seeing’ tourism destinations, which John Urry called ‘the tourist gaze’ (Garrod, Citation2009). Traditionally, the tourist gaze is largely dominated by the photographs that tourism marketers produce for their destinations (Urry, Citation1990), namely through postcards, travel brochures, and magazines. Under the tourist gaze, the formation of a destination image goes through the cycle of sign ‘construction,’ ‘deconstruction,’ and ‘reconstruction … ’ (Urry & Larsen, Citation2011, p. 142). In view of this, the formation of a good destination image cannot deviate from the construction of tourism organizations and the deconstruction of tourists. shows the construction and deconstruction process of a destination image.

Figure 1. The construction and deconstruction process of destination image.

The tremendous growth of the internet has transformed how a destination is described and perceived (Shakeela & Weaver, Citation2016). The birth of social media and digital photographs allowed everyone to create or share their travel experiences. This resulted in diverse subjects (i.e. DMOs, potential members, and tourists) becoming involved in the process of destination image construction.

The photographic medium is now in a state of flux, from WeChat moments, Instagram stories, and Tik Tok. It is not just photographs and videos; now there is also virtual reality, and more advanced technology will appear in the future. Therefore, it is an ever- changing field that needs to be constantly updated.

Destination management organizations (DMOs) remain defined as three levels of organizations that are in charge of the marketing and management of a tourism destination: national authorities, regional or provincial organizations, and local organizations (Presenza et al., Citation2005). Historically, various organizational structures of DMOs have included governmental departments, hotels, restaurants, and travel agencies (Presenza et al., Citation2005). Now, individuals or companies that indirectly contribute to tourism, such as municipal officials, gas stations, airlines, and universities, are also regarded as potential DMO members (Blain et al., Citation2005).

Although the destination image construction of DMOs has been a popular topic in research of the destination image, the importance of the role of potential DMO members in projecting the destination image cannot be ignored. However, it has received little interest in research. Rather, existing research has focused on analyzing photographs produced by specific tourism bureaus, such as national or provincial DMOs, scenic spots, or specific types of photographs (e.g. Hunter, Citation2012; Kuhzady & Ghasemi, Citation2019; Siyamiyan Gorji et al., Citation2021). Also, there are limited studies exploring in detail the destination image projected by other potential DMO members. Thus, a well-recognized problem in previous research studies is that they do not account for the randomness and diversity of projected subjects of destination image and the various modes of representation of destination images.

For these reasons, the purpose of this study is to explore how potential DMO members project a destination image. China Eastern Airlines (CEAir) was selected as a case study to explore for the purpose. The specific reasons for choosing CEAir are elaborated in the methodology section. More concretely, traditional research methods are used to identify how different genres of photography are used to represent tourism destination images in China.

The structure of this study is as follows: Section 2 discusses the previous studies about destination image, photography, and the theoretical background. Section 3 develops the research methodology. Section 4 discusses the research findings of the study. Section 5 presents the conclusion, focusing on the main findings and contributions, along with the limitations in this study and suggestions for future research.

2. Literature review

2.1. Concept of destination image

Destination image is considered an important field of research and has been widely studied, especially in tourism. The definition of destination image has been established by previous research in various ways. For example, Pan et al. (Citation2021) established the definition of destination image as an impression or a perception of a place from people’s travel experience, marketing efforts, and word of mouth. When applied to the country image, it is described as ‘the total of all descriptive, inferential and informational beliefs one has about a particular country’ (Martin & Eroglu, 1993, as cited in Souiden et al., Citation2017, p. 55).

From the perspective of the supply-demand side, researchers have divided destination image into two areas: projected destination image and perceived destination image (e.g. Marine-Roig & Ferrer-Rosell, Citation2018; Picazo & Moreno-Gil, Citation2019). Among them, the projected destination image is the representation of the understanding and impression of a place based on the consideration of tourists (Marine-Roig & Ferrer-Rosell, Citation2018). Picazo and Moreno-Gil (Citation2019) further identified that the projected destination image is considered a deliberate representation designed by tourism marketers using online platforms as a medium, with pictures as the main form.

Furthermore, the projected destination image can be divided into intentional and unintentional (Kozma & Ashworth, 1993, as cited in Deng & Li, Citation2018). The intentional projected image appears in tourist brochures and commercial videos, which always have exquisite pictures and slogans. It is created by tourism hosts and is mainly for marketing purposes. However, the unintentional projected image is mainly generated by showcasing people’s personal lives. It always manifests through popular media, such as films, news reports, and television programs without a marketing-oriented purpose (Ji, 2011, as cited in Deng & Li, Citation2018). In view of this, in the context of social media, photographs associated with destination image should also be included in the category of the unintentional projected image.

As for the perceived destination image, it is the result of tourists’ deconstruction of projected images based on their own individual experiences (Marine-Roig & Ferrer-Rosell, Citation2018). Prior studies have mainly been based on a quantitative method to analyze the perceived image. For example, scholars have found that photographs and moderately long content tend to be more attractive and user engagement tends to be higher (Mariani et al., Citation2016). The valuable, relevant, complete, and interesting information involved in social media posts of DMOs can help tourists generate a positive image of the destination (Kim et al., Citation2017), whereas functional information that may convey the details, such as the location of attraction or the date of an event, is likely to be ineffective (Molina et al., Citation2020).

Moreover, one part of the studies appeared to investigate the difference between the projected destination image and perceived destination image, especially from the perspective of cognitive and affective aspects (Marine-Roig & Ferrer-Rosell, Citation2018; W. Sun et al., Citation2021). However, the appearance of user-generated content (UGC) prompts tourists to participate in the projection of destination image, and the boundaries between the projected destination image and the perceived destination image seem to become blurred (Deng & Li, Citation2018). Although there has been an increase in research conducted on the perceived destination image from the perspective of the demand side (e.g. Deng et al., Citation2019; M. Sun et al., Citation2015; W. Sun et al., Citation2021), it cannot be denied that the projected destination image remains important.

Overall, combining the views of Pan et al. (Citation2021) and Souiden et al. (Citation2017) in this study, the destination image refers to the country image, that is, China’s destination image. And the projected destination image refers to a representation of China that is deliberately constructed by CEAir through a different series of photographs on Facebook. This study focuses on CEAir-generated content and the projected image of China, but does not include UGC content from tourists.

2.2. Visual content and destination image

Extensive studies identified a generalized finding that visual content (e.g. photographs and videos) is more effective than text (Picazo & Moreno-Gil, Citation2019). Therefore, the use of photographs has become a common marketing tool for tourism marketers. Early scholars mostly focused on the usage of photographs in print media to investigate the projected destination image. For example, Milman (Citation2012) assessed the role of postcards in the Berlin image and Hunter (Citation2012) examined the image of Seoul, Korea, by viewing photographs on tourist brochures and guidebooks. However, these photographs in print media are carefully taken by professional photographers and lack objectivity and accuracy (Xiao et al., Citation2020).

With the development of the internet, some scholars started to evaluate the projected destination image under the context of social media. Thus, an interesting finding was presented: landscape photography plays the role of a leading attribute in representing the projected image (e.g. Kuhzady & Ghasemi, Citation2019; Noordin et al., Citation2021; Siyamiyan Gorji et al., Citation2021). As for a nation, photography, especially landscape photography, is deemed as a representation of the national character (Jäger, Citation2021, p. 118).

Similarly, in China, visual content also plays an extraordinary role in the construction of a destination image, touching on various forms of media. For instance, Hsu and Song (Citation2013) examined the projected image of Hong Kong and Macao in travel magazines from Mainland China. They also confirmed that the leading attributes are related to culture, history, art, and leisure activities (Hsu & Song, Citation2013). Other scholars, such as Shani et al. (Citation2010), M. Xu et al. (Citation2020), and J. Li et al. (Citation2021), analyzed and compared the projected image in documentaries.

In the era of new media, scholars focused more on researching what appears on social media in the form of text or dynamic visual form, such as travel blogs (e.g. Tseng et al., Citation2015), YouTube videos (Jiao et al., Citation2022), and Tik Tok short videos (e.g. Y. Li et al., Citation2020). Significantly, research taking photographs as data is also evolving (e.g. Deng et al., Citation2019; Zhao et al., Citation2018). However, most researchers are dedicated to the study of perceived destination image from tourists’ UGC content (e.g. M. Sun et al., Citation2015). Only some of the studies focused on China’s projected image from the supply side. Moreover, most Chinese researchers center upon on Chinese domestic dissemination channels and domestic tourists (e.g. Zhao et al., Citation2018). There is a lack of research on Chinese destination images from a cross-cultural perspective.

Unlike traditional forms of cultural communications, the appearance of social media offers a new, interactive representation of destination images through the lens. This situation is not unique to the Western context when applying marketing and visual marketing in tools to distribute the destination images. Although the Chinese context is derived from the Western framework, the destination image is developed in more distinctive ways. The various projection subjects and various modes of representation are the subject of this article. This is why this study focuses on the Chinese context.

2.3. Projected destination image and semiotic theory

Urry and Larsen (Citation2011) claimed that in the context of tourism, all landscapes are endowed with the meaning of ‘signs’ (p. 17). When travelers escape their daily life and walk into a strange place, they collect visual signs, such as photographs of buildings and landscapes, to fulfill their imagination of a new place, life, and people (Stone & Nyaupane, Citation2019). There are various kinds of signs in our daily life, such as paintings, buildings, music, and languages, which are deemed as signs with special meaning (Golinvaux & Evagelou, Citation2017). Semiotics has laid a solid theoretical foundation for the research of productive activities and cultural communication.

With the development of society, semiotic analysis is gradually used for multidisciplinary communication and development. The linguist Ferdinand de Saussure defined that linguistic signs consist of ‘the signified’ and ‘the signifier’ (Golinvaux & Evagelou, Citation2017). The signifier belongs to the field of the physical world (such as vision, taste, and smell), while the signified belongs to the field of the psychological world (such as feelings and notions) (Lian & Yu, Citation2017). Later, Pierce proposed his semiotic triangle, which included three elements: representamen, interpretant, and object. Echtner applied semiotic analysis to the tourism industry, in accordance with Pierce’s semiotic triangle (Golinvaux & Evagelou, Citation2017), and highlighted the relationships between objects (destination), signs (such as advertisements), and tourists (Arefieva et al., Citation2021).

It is a fact that content analysis, visual analysis, and semiotic analysis are the three most common approaches used in tourism-related photograph research (Deng et al., Citation2019). For example, Hunter (Citation2016) found that Seoul’s destination image tends to be a social-semiotic construction through a comparative semiotic analysis of visual representation. Lian and Yu (Citation2017) stated that travel resources, facilities, and services are three elements to represent the destination image of Huangshan in China through content analysis. Furthermore, Tomaž and Walanchalee (Citation2020) extend the representation of destination image on social media through visual-content analysis. Fayzullaev et al. (Citation2021) explained that heritage is a dominant attribute of Uzbekistan’s destination image through content-semiotic analysis.

Although the exploration of the projected image on social media is rising, more work needs to be done within the parameter of place representation modes and how destination image is created. The construction of a destination image is a long-term dynamic process affected by the subject of projection, spatial and temporal distribution, and dissemination channels. There is still a research gap regarding how potential DMO members construct a destination image and how different genres of photography represent a touristic place. Therefore, this study applies the basic theory of semiotics as research theoretical background and conducts traditional research methods to explore China’s projected destination image.

The following research questions are proposed:

RQ 1: How are different genres of photography on the official Facebook page of China Eastern Airlines representing the image of places in China?

RQ 2: What visual strategies are most often used by CEAir in constructing China’s destination image?

RQ 3: What kind of destination image do photographs from CEAir convey of China to potential tourists?

3. Methodology

The destination images are closely linked to people. Texts about the destination image are created by specific people, which indirectly reflect people’s personal experiences, opinions, and interests (McKee, Citation2003). Furthermore, the essence of the destination image is to tell a story about a place by using audio-visual language to express the themes and core of it. Therefore, textual analysis can better infer the intentions and purposes of text providers and help us to understand the meaning behind these audio-visual languages.

This study focuses on textual analysis methodology. In view of most previous research used to adopt single research methods, or random combinations of content analysis, visual analysis, and semiotic analysis, methods used in this study also mainly comprise visual and semiotic analysis. However, this study introduces multimodal discourse analysis as a supplementary method to provide a more holistic analysis, covering different angles of the topic in this study.

Multimodal discourse analysis combines auditory, visual, touch, and other multiple sense modes and aims to explore the creation of meaning through language, photographs, gestures, and other semiotic resources (D. Zhang, Citation2009). In recent years, it has been used extensively in tourism research (e.g. Isti’anah et al., Citation2021; Krisjanous, Citation2016). In this study, the photographic data contain two main modes: the text mode and the image mode ().

3.1. Sample selection and data collection

The projected image of China refers to images represented by the Facebook official page of China Eastern Airlines (@CEAir). The case of China’s projected image is selected because China has become a popular travel destination for international tourists. Despite the pandemic, according to the Annual Report of China Inbound Tourism 2021, China ranks sixth in the list of popular destinations that global tourists plan to visit ().

Table 1. The top six destination that global tourists plan to visit.

Airlines are indeed key partners for any DMO to reach the international stage (Al Saed et al., Citation2020; Morgan et al., Citation2003). Whether for tourism purposes or otherwise, when customers choose the services of an airline, it means they are likely to be interested in a particular travel place (Al Saed et al., Citation2020). In order to boost sales, airlines need to participate in the promotion of destinations. Therefore, this co-branding effort contributes to the construction of a tourism destination image (Al Saed et al., Citation2020; Frossard et al., Citation2017).

Airlines are uniquely positioned to construct national destination images on the international stage. In terms of China’s aviation industry, in 2022, all sectors attained 520 million passengers annually, of which CEAir attained 42 million of those passengers (Civil Aviation Administration of China, Citation2023). With the SkyTeam alliance, CEAir’s aviation transport network covers 1,088 destinations in 184 countries and regions worldwide (China Eastern, Citationn.d.). This gives CEAir more opportunities to directly reach international travelers.

In addition, CEAir has a large fan base on Facebook. By the end of 2022, CEAir had over 5.3 million fans on Facebook (). This shows its huge influence on social media platforms. CEAir has already acted as a brand representative for China, and therefore it can ably promote the spread of China’s destination image.

Table 2. Introduction of official Facebook page of airlines.

After connecting with the Facebook account operator of CEAir through WeChat, permission was obtained to use the photographs within the parameters of this research project. A total of 35 posts published by @CEAir’s official page from 1 July to 31 July 2022 were collected for analysis as research data.

shows the criteria of the sample selected in detail. Posts that included one or multiple photographs were obtained and extracted. However, some posts were excluded from this study because of their content or form. First, videos and posters entirely designed by vector images were not included. Second, reposted posts were not included. This study mainly drew on the original posts published by CEAir. Third, news reporting posts about the airline itself were excluded. Lastly, photographs that were unrelated to China as a travel destination or irrelevant to traveling were also omitted. As a result, a total of 26 posts with 40 photographs were obtained for the next step.

Table 3. Criteria of sample selected.

3.2. Data analysis

In this study, semiotic analysis, visual analysis, and multimodal discourse analysis were used to analyze the data. In the beginning, semiotic analysis was adopted to categorize the photographic data into themes. Based on the semiotic theory, a sign has both denotative and connotative meanings. Denotation meaning refers to a description of a certain object and only delivers the data information (Rachman et al., Citation2019). The denotative meaning points out the objects by words and explains their relationship, while connotative refers to how to describe an object. The connotative meaning includes positive and negative associations, which are associated with feelings, emotions, values, and perspectives of a community (Rachman et al., Citation2019).

According to the denotative information displayed on the photographs, 40 photographs were classified into five themed groups. Following the similar category setting of Noordin et al. (Citation2021), the five groups were labeled as follows: food, architecture, landscape, staff, and activity. They were then analyzed in order according to the category. shows the percentage of each category.

Table 4. Categorization of samples.

In the next step, semiotic analysis will be used to extract the signs unique to China that are included in the photographs, such as the elements of traditional Chinese architecture and food. Then, visual analysis will focus on the analysis of image mode, including the genre, photographic angle layout, color, and framing. Multimodal discourse analysis will focus on analyzing the meaning of text mode, including text on photographs, post titles, content, hashtags, and interaction statistics.

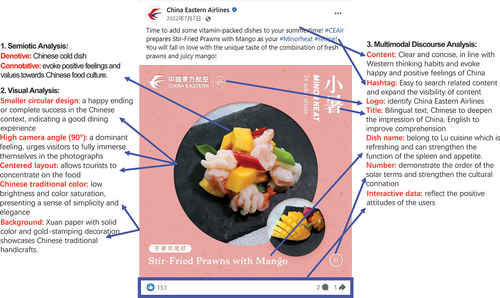

Finally, this study summarizes what connotative meanings are conveyed by these elements, different modes, and photographic techniques. It also attempts to discover some connection between photography and destination image. , taking the photograph categorized under ‘food’ as an example, elaborates on the steps of data analysis.

4. Research findings

4.1. Food signs: a delicious, intelligent, healthy, and simple China

Food reflects a nation’s history and culture. The data analysis category frequency showed that three photographs were related to food and tea (). As a common object of still life photography, food and tea are given human meaning to make them attractive (Bate, Citation2016, p. 139).

showcases the dish that is designed for an in-flight meal, and it matches the weather and seasonal characteristics of the 24 solar terms. According to visual analysis, the whole background is filled with Chinese calligraphy paper known as Xuan paper (or rice paper). Xuan paper originated from the Tang Dynasty and is acknowledged as a witness to millennia of Chinese history and a carrier of Chinese paintings and calligraphy. Using this form as the background showcases traditional Chinese handicrafts.

In the foreground is a smaller circular design, which shows the ingredients of the dish. The main and secondary parts are clearly distinguished. Moreover, the circular design means a happy ending or complete success in the Chinese context, indicating a good dining experience. It has adopted a high camera angle (90°), which is the most popular angle for food photography on Instagram (Yang, Citation2019). Also, the high camera angle represents a dominant feeling, meaning that it urges visitors to fully immerse themselves in the photographs. Additionally, the centered layout allows tourists to concentrate on the food.

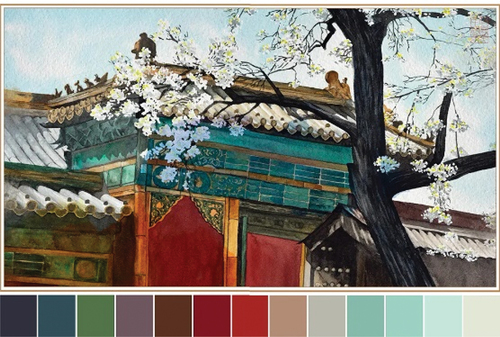

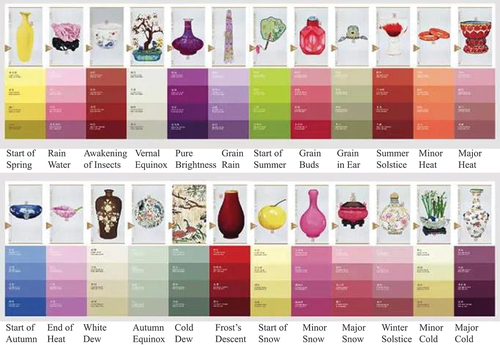

In terms of color, it is painted with traditional Chinese colors, which will be discussed in more depth later. Here, it is necessary to first introduce China’s 24 solar terms. China’s 24 solar terms are an integrated knowledge system that ancient Chinese used to observe, explore, and make conclusions about astronomy, climate, and phenology based on the sun’s motions in the Chinese zodiac (W. S. Xu, Citation2017). Ancient Chinese divided a year into 24 segments (each segment is called a solar term) and then applied them to agricultural production and daily lives (W. S. Xu, Citation2017). According to the climate and seasonal characteristics, each solar term corresponds to eating a dish, which means following the laws of nature.

In regard to color, the Chinese traditional color system originated from five colors (white, black, red, yellow, cyan) and is based on the philosophy of Yin-Yang and the Five Elements (metal, wood, water, fire, and earth) (Wang, Citation2022). This system reflects the ancient perception of nature’s colors and their aesthetics. Most pigments are made from plants and minerals, so they are not particularly bright. When painting, the painter used water to tone down the color saturation, presenting a sense of simplicity and elegance (). The traditional colors can easily be associated with Chinese architecture or Chinese painting style. Furthermore, the ancient Chinese used poetry and painting to depict the 24 solar terms, connecting color to space and time, and thus creating the unique colors of 24 solar terms (W. S. Xu, Citation2017) ().

Figure 5. Application of Chinese traditional color in painting.

Figure 6. The 24 solar terms and Chinese traditional color.

With the aid of traditional color, traditional craftsmanship and 24 solar terms, the dish reproduces Chinese cultural concepts. The traditional colors make each solar term more distinctive and memorable, and the 24 solar terms deepen our understanding of seasonal food. Through the bond of the 24 solar terms, the traditional Chinese colors are bound with the seasonal food, making it more aesthetically pleasing and thus influencing people’s desire to eat. The whole picture looks like not just food photography but also a Chinese painting full of ‘atmosphere’ and ‘spirit.’ When tourists talk about seasonal food, they may make a connection with colors and immerse themselves to experience the cool or hot solar terms. The photograph highlights the healthy lifestyle of Chinese people by harmonizing their diet with the seasons and living in tune with the times. Meanwhile, they demonstrate Chinese people’s unique aesthetics in constructing a delicious, wise, and healthy China for overseas tourists.

showcases Chinese tea. The background is a photograph of a cup of tea with a Gaussian blur. The midground adopts the close-up of the tea, displaying the clear detail of the teacup, and the foreground uses a vector image of an airplane window and prompts tourists to focus on the tea. This photograph adopts the 45° camera angle and diagonal layout, which gives it a sense of dimensionality and depth. When tourists see this photograph, it gives them the feeling that they are sitting at the table with the tea. The color is warm toned, giving us a cozy and comfortable feeling.

Tea culture is one representative of Chinese traditional culture. Influenced by Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism, nature, joy, and harmony have become an essence of tea culture (Gao, Citation2021). This photograph creates a quaint atmosphere, and when visitors see it, they imagine themselves relaxed and serene while drinking tea. Through Chinese tea culture, CEAir constructs a simple and relaxed China.

4.2. Traditional architecture signs: an encyclopedical and idyllic China

The years 2019 to 2022 were a challenging period. Because of the influence of Covid-19, the global economy faced a lean time and tourism was hard to develop. During this time, social media postings seemed to serve as one of the most effective strategies to promote and advertise brand awareness (Ramakhrisnan, Citation2020).

Morgan et al. (Citation2002) found that when places are imbued with a rich emotional meaning, they become emotionally appealing to tourists. The campaign ‘Find the most of China’ adopts destination marketing and defines the position of China, which is a profound, cultural, and encyclopaedical country. shows the two posters of the advertising campaign. Photographs of traditional Chinese architecture serve as the background, and four relevant vector images are placed around the corners. In addition, the abstract cabin door, advertising slogan, and hashtag #ConnectWondersandHearts are placed in the middle of the poster, from top to bottom.

Figure 8. Posters of ‘find the most of China’ series (the top one sets as ; the bottom one sets as ).

is a top view of the Jin Temple in Taiyuan, Shanxi Province, which is a typical Northern Song Dynasty building. The corners of the roof are cocked, and the eaves look like an arc, demonstrating the design aesthetic of Song Dynasty architecture. The garden style design, coupled with axial symmetry, is in accordance with the terrain and blends with nature, reflecting the Chinese philosophy of ‘the unity of heaven and man.’ Influenced by this philosophy, ancient Chinese combined nature with architecture and achieved idyllic seclusion in the city. A high camera angle shows a magnificent traditional building.

shows the landscape of Hangzhou. The eye-level camera angle gives tourists an intimate feeling and is easy to integrate into the view. Vector elements around both posters provide clues for visitors to guess the destination, and the vivid cabin door closely links the brand of CEAir with China’s tourism industry. This advertising campaign stimulates visitors’ interest and curiosity about China, achieving interactive meaning. It is also a recontextualization of Chinese philosophy.

Since the 1880s, Kodak’s roll-film camera design has progressively developed amateur photography and people started to focus on preserving their memories and recording their ‘Kodak moments’ in daily life (Munir & Phillips, Citation2005). Later, Kodak’s advertising showed the spirit of adventure and urged people to take vacations and return with photographs of far-off cultures and landscapes (Munir & Phillips, Citation2005). More than 3,000 signs were placed on U.S. highways with the message ‘picture ahead, Kodak as you go,’ reminding people of the beauty that ‘deserves to be preserved’ (Munir & Phillips, Citation2005). Tourists collected these photographs and constructed ‘the visual inventory of vistas around the U.S’ (Hill, Citation2019, p. 39).

Similarly, the ‘Find the most of China’ series arranged the ‘most’ signs on Facebook to influence the ways of seeing and perceiving a place. As people head to their destination and press the shutter, they begin the ‘second moment of photographic homogenization’ (Hill, Citation2019, p. 38). In the context of social media, virtual technologies, such as digital photographs, are about communicating with people’s emotions to a large extent rather than just capturing ‘Kodak moments’ (Foroudi et al., Citation2019). Before the trip, all the information from posters, such as the hashtag #ConnectWondersandHearts, builds an emotional link with tourists, and these photographs can be a symbol of knowledge and status for tourists. Through sharing and possessing these photographs, the destination image is generated, even if tourists have not yet traveled to the place. The casual capture and collection, ignoring the spatial and temporal considerations, perhaps have gone beyond the traditional ‘Kodak moments,’ and this form of photography has become a new mode of representation of the destination image.

4.3. Landscape signs: an appealing and modern China

Antrop and Van Eetvelde (Citation2017a) pointed out that landscape not only refers to geography and the environment but is also a source of aesthetics and expression. In a different context, landscape can represent different meanings. Jäger (Citation2021) took Britain as an example and analyzes its picturesque language. He emphasized that ‘these photographs used a common “language” for a wide variety of landscapes that represented what should be considered as belonging to Britain’ (p. 125).

In this study, CEAir mainly uses natural Chinese scenery to represent China’s destination image. is a group of photographs with the same design elements. They all adopt blurred backgrounds, and in the midground there is a clear close-up, which focuses on the scenery. Using an airplane window as the foreground attracts tourists’ attention. Basically, the airplane window is used to frame the key points of photographs (i.e. waterfall, river, stars, and buildings), leading the visitors’ eyes to the middle of the frame. Framing is a common shooting method used by photographers, such as windows on buildings, doorframes, holes in walls, slits, and car windows. Also, flowers and trees are common frames used in photography. This way of composition serves to make the subject more noticeable while making the photographs more layered. The scenery in the airplane window makes it difficult to distinguish between virtual and reality, making the scenery seem more dreamlike and mysterious.

In China, photography, poetry, and painting all pursue the expression of ‘yijing’ (意境). The term ‘jing’ (境) is an intense aesthetic experience in which one’s perception of an object achieves a perfect union with the meaning represented by that object. In other words, CEAir uses ‘jing’ as the common sign for the natural landscape that represents China’s destination. It is similar to the ‘picturesque’ concept, which seeks to give people an infinite imagination outside the picture. In addition, scatter perspective (also called shifting perspective) was a common perspective used by Chinese painting artists (Bao et al., Citation2016). Different to the focus perspective adopted by the West, the scattering perspective pursues the expression of a ‘different angle of view, different scenery.’ This expression is also used in photography, resulting in a uniquely Chinese style of landscape photography. The panoramic view highlights the beauty of China’s mountains and rivers, drawing a far social distance between the tourists and the landscape and prompting curiosity in people to come and visit.

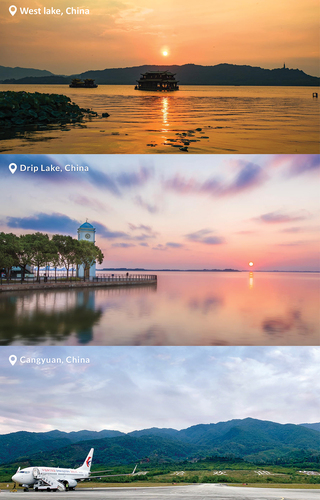

show the natural and urban landscapes, respectively. They use a simple design, indicating the geographical location only in the upper left corner. The posts are to strengthen foreign tourists’ recognition of China’s destination image by identifying the landscape photograph that is most similar to an emoji. Taking as an example, the layout makes each photograph full of stories, leaving an opportunity for tourists to imagine. They can judge whether it is sunrise or sunset, departure, or landing.

Figure 10. Natural landscape published on World Emoji Day.

Figure 11. Urban landscape published on World Emoji Day (the photograph of Shanghai sets as and the photograph of Beijing sets as ).

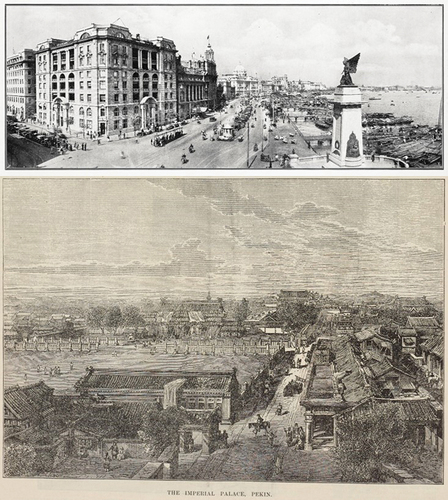

shows the landscapes of Shanghai and Beijing, China’s most representative cities. The photograph of Shanghai () is rich in color, with natural light and city lights interplaying, and the warm tones of the buildings contrast with the cool tones of the sky, prompting a sense of storytelling throughout the city. The crisscrossing traffic, acting as guiding lines, draws people’s attention to Shanghai’s skyscrapers. , with the black and white tones, brings us back to colonial history. The photograph is not dynamic or energetic and could make us feel depressed compared to a modern-day photograph. The exotic architecture is reminiscent of Shanghai, which was then a British Concession. For a long period, the concession culture represented Shanghai culture. Today, Shanghai’s World Financial Center, Jinmao Tower and Center Tower have become landmark buildings, highlighting the city’s open, innovative, and inclusive culture.

Figure 12. The old photographs of Shanghai and Beijing (the first photograph of old Shanghai sets as and the second photograph of old Beijing sets as ).

Unlike Shanghai, Beijing gives the impression of being traditional and cultural. As seen in , the courtyard house (Siheyuan in Chinese) as the representative architecture of Beijing is the focus of the photograph. Following the road guidelines, no traces of modernization can be detected. However, now the different shapes of the skyscrapers are majestic, highlighting China’s style (). The dynamic, misty clouds highlight the historical changes in Beijing.

Antrop and Van Eetvelde (Citation2017b) stated that some landscapes produce different views due to daylight, weather conditions, and climate change, a phenomenon that researchers call ephemeral landscapes. In addition, ephemeral landscapes also include moving objects, people, and animals that appear in the landscape. Based on this concept, the following photographs () taken from aircraft landings, take-offs, stops, daylight changes, and movement of people can be called ephemeral landscapes. Both the warm evening sunset and the blue sky with white clouds depict a positive attitude. The use of wide-angle lenses as well as close-ups showcase the corporate strength of CEAir and reflect the strength of China, shaping China as a powerful and attractive destination.

4.4. People signs: a responsible, powerful, and diligent China

Locals are one of the key representatives of the destination image. The impression of locals as perceived by tourists from other countries affects the overall evaluation of the country. According to the 2019 China National Image Global Survey (Mandarin), ‘industrious’ and ‘devoted’ are the two most common words to describe Chinese people. In sample posts of CEAir published on Facebook, snapshots of China Eastern Airlines staff take up a large part (37.5%).

The images that make up are taken from the daily work of CEAir staff. Interestingly, what they all have in common is that they are wearing white or blue masks and blue gloves, which became compulsory wearing in the COVID-19 pandemic environment. The first four photographs show flight attendants conducting sanitation, inspection, and service of the check-in counter and cabin. They stand upright, but relaxed, not stiff, their eyes focused and determined. From their body language, we see they take pandemic protection seriously and responsibly.

The middle four photographs show the work of ground staff. Through special angles and close-ups, the details under the work of the pandemic are shown. The photographs show staff working in high temperatures. They are still dressed neatly and without a hint of slackness. Their movements, such as carrying a trailer with both hands, show their tough but serious work. For instance, in the 12th photograph in , the subject’s body is tilted at an angle of about 45 degrees, and the weight of the box can be intuitively felt. Also, the last three photographs use the aircraft engines and the staff for comparison. The use of tools, such as ladders, and the assistance of many people in the picture show the physicality of the work.

All the photographs are attributed to one genre of photography, which is called candid photography. The most important feature of candid photographs is that they are considered to be real. This is because the moment the shutter is pressed it looks as though the person has been photographed without being aware (Berger & Barasch, Citation2018). Compared with posed photographs, candid photographs appear to give a natural perspective on how someone looks and behaves when they are not watching (Berger & Barasch, Citation2018). This style of photograph typically contains no strong visual composition. Instead of deliberately showing the interaction with passengers, this group of snapshots captures some details of the work behind the scenes of the staff, giving an insight into the hard work of the countless people behind every safe flight. These so-called ‘candid moments’ allow us to quickly capture what the snapshot is trying to convey and make the content more convincing. The daily work life of the staff presents the brand image of the CEAir on the one hand and provides a glimpse into Chinese service on the other, leading overseas visitors to learn more about China’s contribution to clean energy, safe flight, and pandemic prevention. CEAir constructs a destination image of China as a responsible and hardworking country with the help of people signs.

4.5. Ethnic minority signs: a harmonious and United China

China is a united and multi-ethnic country where 56 ethnic groups live, forming a Chinese family together. ) shows flight attendants from China Eastern Airlines singing and dancing with the Wa people in Yunnan Province. Locals dressed in traditional ethnic minority costumes interact enthusiastically with the flight attendants representing the Han. From their body language, such as the smiles on their faces, raised arms, and body twisting range, we can feel that this is a harmonious and beautiful moment.

Figure 15. Photograph of tourism activities (the top one sets as ) and the bottom one sets as )).

) shows ethnic minority children and the flight attendants playing with the model plane together. Children represent hope and the future no matter what country they are in. Their smiling faces and applauding movements are a mirror image of joy and happiness. The flying model airplane signifies that dreams set sail from here. This kind of photograph belongs to a form of travel photography, a recording of a place in terms of its people, landscape, culture, and history as well as customs (Pradhan, Citation2016). Meanwhile, travel photographs are deemed as a representation of personal experience and even social experience (Ting & McKercher, Citation2016).

These two travel photographs reveal what the flight attendants saw and experienced in the minority areas and their perceptions and expectations of the local people and culture of Yunnan, as well as what they would like to remember from their travel experiences. The authentic travel experience with a display of traditional costumes and ethnic minority culture in China is likely to have a particular appeal to tourists who are keen to satisfy their curiosity. CEAir used these two photographs to show the happy life of an ethnic minority, depicting the deep friendship between the Han people and ethnic minority people. Travel photography becomes a flexible way to promote branding without making people feel strongly overwhelmed. At the same time, they implant national spirit into advertising and demonstrate the ‘Chinese dream’ that China pursues to become a strong and prosperous country and strives for the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation and the well-being of its people.

The background of the two photographs is the fresh natural environment. They both adopt an eye-level camera angle and bright tones, prompting tourists to get in touch with the people in the photographs and share the joyful moments with them. These travel photographs represent a different destination image of China that remains focused on spiritual connotations (harmonious and united China) rather than just outward expressions (such as clean and eco-friendly China).

5. Conclusions

5.1. Projected destination image construction

This study examines how CEAir, a potential DMO member, constructs the tourism destination image of China. Through semiotic analysis it was found the most frequently used signs in constructing China’s destination image were people, landscape, food, architecture, and ethnic minorities. The visual analysis reveals that eye-level angle is the main photographic angle in candid photography, landscape photography, and travel photography, while a high camera angle is the common photographic angle in still life photography and architecture photography, such as food and temples. The color tone of these photographs all adopted bright colors, conveying a sense of hope, beauty, and positivity. By attaching cultural meaning, different genres of photography all become a mode of representation of destination image.

Meanwhile, CEAir uses its own corporate image to promote China’s destination image. For one thing, airline elements combined with photographs become the most frequently used visual strategy, such as the cabin door and airplane window. Snapshots with ‘candid moments’ also lead tourists to learn more about the stories behind the airline staff. They each use a common design template that allows people to collect signs while stepping into the tourist place that CEAir pre-established.

During the construction process, Chinese traditional culture served as a ‘special gaze’ participating in the construction of China’s destination image. In this study, the ‘special gaze’ focuses more on how Chinese culture influenced the way people view and perceive/project places. It emphasizes CEAir’s ability to represent Chinese culture in a unique and attractive way through specific photographic techniques, visual choices, and multimodal combination, in order to construct an attractive destination image. Previous studies have emphasized the selection and presentation of the subject under shot, such as landscape, food, and architecture (e.g. Deng et al., Citation2019; M. Sun et al., Citation2015; M. Xu et al., Citation2020). For example, M. Sun et al. (Citation2015) found Chinese tourists tend to take photographs of snow-covered mountains reflected in lakes. This is because of the Yin-Yang concept in Chinese philosophy. Different from those studies, this study claims that the different photographic techniques, layout design, and color match are all essentially the unique contributions to the construction of China’s destination image.

Overall, CEAir depicts China as a historic, powerful, and fascinating oriental country devoted to global development. More specifically, delicious, intelligent, healthy, simple and relaxed, encyclopaedical, idyllic, appealing, modern, responsible, powerful, diligent, harmonious, and united are all words to describe China. Interestingly, it was found that the representation of destination image does not necessarily have to rely on landscape photography. A variety of photographic genres, such as travel photography, candid photography, still life photography, and architectural photography, can be modes of representation of the destination image through the choices of visual language.

5.2. Contributions to literature and limitations

In this section, the theoretical and practical contributions as well as the limitations of methodology, data collection, and sample types are outlined. From the theoretical viewpoint, this study successfully explores the destination image projected by the potential DMO member airlines, which expands the research subjects in the field of the destination image.

More importantly, this study attempts to expand the understanding of destination image construction by exploring how different genres of photography use specific visual language to construct a destination image under the gaze of Chinese culture. Here, visual language includes the choices of subject under shot, photographic techniques, layout design, and color match. This attempt may be innovative to destination image research. Therefore, the concept of ‘special gaze’ serves as a theoretical implication that contributes to a deeper understanding of destination image construction. It is important to consider visual language in the construction of the destination image; broadly speaking, this is instructive for other places in the tourism context.

From the practical viewpoint, this study provides a valid model with three different analytical methods. The attempt to adopt multimodal discourse analysis provides a possibility to explore cultural context and discourse on the projection of destination image. The analytical model can also be cross referenced for future research.

However, the study has several limitations. Firstly, semiotics is considered to be a subjective form of analysis as it requires a rather personal experience and perspective to explain how signs generate meaning. Different researchers have different ways of interpreting and analyzing photographs. In addition, multimodal discourse analysis, as a supplementary method, seems to provide new insights with the interaction of different visual modes. However, it has not been focused on as much as other research methods. Future research efforts may try to focus on multimodal discourse analysis to explore more modes that represent the destination image.

Secondly, the data selected in this study were dated from 1 July to 31 July in the year 2022. The study took this short period as the sample to identify China’s projected destination image. However, the construction of the destination image is dynamic and evolving regardless of the demand side or the supply side (W. Sun et al., Citation2021). It is therefore suggested that future researchers should consider extending the period of data, such as data collection, from the last one or two years since 2022. In particular, they should analyze the change of destination image in the period of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Thirdly, DMO members may tend to share positive photographs and use the positive hashtag with the general public, which may lead to an overperforming destination image and fail to convince the audience. Future research is called for an effect analysis of travelers to extend the general conclusion.

Acknowledgments

First, I would like to appreciate all those who helped me during the process of this project. I am especially grateful to my supervisor, Dr. Rodrigo Hill, for his patience, encouragement, and professional guidance. I would like to thank all the staff of the Waikato Library for their support and help and also for the assistance from Dadon Rowell. Additionally, I would like to thank my family, including my parents and grandparents, for their encouragement.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Tengfei Han

Tengfei Han is a PhD candidate in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at the University of Waikato, Hamilton, New Zealand. Her research interests include place and culture, human geography, photography, representation, and tourism (E-mail: [email protected]).

References

- Al Saed, R., Upadhya, A., & Saleh, M. A. (2020). Role of airline promotion activities in destination branding: Case of Dubai vis-à-vis emirates airline. European Research on Management and Business Economics, 26(3), 121–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iedeen.2020.07.001

- Antrop, M., & Van Eetvelde, V. (2017a). The holistic nature of landscape–landscape as an integrating concept. In Landscape perspectives (pp. 1–9). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-024-1183-6_1

- Antrop, M., & Van Eetvelde, V. (2017b). The multiple meanings of landscape. In Landscape perspectives (pp. 35–60). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-024-1183-6_3

- Aquino, L. (2016). Picture ahead: Kodak and the construction of the tourist-photographer. The Social Service of Commerce. https://centrodepesquisaeformacao.sescsp.org.br/revista/edicao_especial_ingles.pdf#page=82

- Arefieva, V., Egger, R., & Yu, J. (2021). A machine learning approach to cluster destination image on instagram. Tourism Management, 85, 104318–. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2021.104318

- Bao, Y., Yang, T., Lin, X., Fang, Y., Wang, Y., Pöppel, E., & Lei, Q. (2016). Aesthetic preferences for Eastern and Western traditional visual art: Identity matters. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1596–1596. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01596

- Bate, D. (2016). Photography: The key concepts (2nd ed.). Routledge. https://do-org.ezproxy.waikato.ac.nz/10.4324/9781003103677

- Berger, J., & Barasch, A. (2018). A candid advantage? The social benefits of candid photos. Social Psychological & Personality Science, 9(8), 1010–1016. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550617732390

- Blain, C., Levy, S. E., & Ritchie, J. R. B. (2005). Destination branding: Insights and practices from destination management organizations. Journal of Travel Research, 43(4), 328–338. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287505274646

- China Eastern. (n.d.). About China Eastern. https://www.ceair.com/global/en_static/AboutChinaEasternAirlines/intoEasternAirlines/chinaeasternInto/index.html

- Civil Aviation Administration of China. (2023, December 25). Statistical bulletin of civil aviation industry development in 2022. https://www.caac.gov.cn/English/Research/Reports/Statistical/202312/t20231225_222458.html

- Deng, N., & Li, X. (2018). Feeling a destination through the “right” photos: A machine learning model for DMOs’ photo selection. Tourism Management, 65, 267–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2017.09.010

- Deng, N., Liu, J., Dai, Y., & Li, H. (2019). Different cultures, different photos: A comparison of Shanghai’s pictorial destination image between East and West. Tourism Management Perspectives, 30, 182–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2019.02.016

- Edwards, E. (2011). Tracing photography. In J. Ruby & M. Banks (Eds.), Made to be seen: Perspectives on the history of visual anthropology (pp. 159–189). University of Chicago Press. https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.ezproxy.waikato.ac.nz/lib/waikato/reader.action?pq-origsite=primo&ppg=166&docID=836896

- Fayzullaev, K., Cassel, S. H., & Brandt, D. (2021). Destination image in Uzbekistan – heritage of the silk road and nature experience as the core of an evolving post soviet identity. The Service Industries Journal, 41(7–8), 446–461. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2018.1519551

- Foroudi, P., Mauri, C., Dennis, C., & Melewar, T. C. (Eds.). (2019). Place branding: Connecting tourist experiences to places (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315600567

- Frossard, M. S., Castro, R., & Fraga, C. (2017). Construction of the image of the city of Rio de Janeiro as a tourist destination through airline posters (1930–1960). Journal of Turismo & Development, 1(27/28), 2039–2048. https://doi.org/10.34624/rtd.v1i27/28.10433

- Gao, G. (2021, June 9–10). A comparative study of the aesthetic characteristics of Chinese and Japanese tea culture [ Paper presentation]. The 2nd International Conference on Language, Communication and Culture Studies (ICLCCS 2021), Moscow Russia. https://doi.org/10.2991/assehr.k.211025.037

- Garrod, B. (2009). Understanding the relationship between tourism destination imagery and tourist photography. Journal of Travel Research, 47(3), 346–358. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287508322785

- Gasawneh, J. A. A., & Adamat, A. M. A. (2020). The relationship between perceived destination image, social media interaction and travel intentions relating to neom city. Academy of Strategic Management Journal, 19(2), 1–12.

- Golinvaux, A., & Evagelou, I. (2017). The role of semiotics in tourism destination branding through social media: The case of Switzerland. Journal of Travel Research, 16(1), 203–215.

- Hill, R. (2019). Place imaginaries: Photography and place-making at Te Awa River ride [ Doctoral thesis, University of Waikato]. University of Waikato Research Commons. https://researchcommons.waikato.ac.nz/handle/10289/12797

- Hsu, C. H., & Song, H. (2013). Destination image in travel magazines: A textual and pictorial analysis of Hong Kong and Macau. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 19(3), 253–268. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356766712473469

- Hunter, W. C. (2012). Projected destination image: A visual analysis of Seoul. Tourism Geographies, 14(3), 419–443. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2011.613407

- Hunter, W. C. (2016). The social construction of tourism online destination image: A comparative semiotic analysis of the visual representation of Seoul. Tourism Management, 54, 221–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.11.012

- Isti’anah, A., Rahmasari, S., & Lauwren, S. (2021). Post-pandemic Indonesian tourism promotion in Instagram: Multimodal discourse analysis. Journal of Modern Languages, 31(2), 46–76. https://doi.org/10.22452/jml.vol31no2.3

- Jäger, J. (2021). Picturing nations: Landscape photography and national identity in Britain and Germany in the mid-nineteenth century. In J. Schwartz & J. Ryan (Eds.), Picturing place (1st ed., pp. 117–140). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003268260-8

- Jiao, Y., Meng, M. Z., & Zhang, Y. (2022). Constructing a virtual destination: Li Ziqi’s Chinese rural idyll on YouTube. Journal of Teaching in Travel & Tourism, 22(3), 279–294. https://doi.org/10.1080/15313220.2022.2096178

- Kim, S. E., Lee, K. Y., Shin, S. I., & Yang, S. B. (2017). Effects of tourism information quality in social media on destination image formation: The case of Sina Weibo. Information & Management, 54(6), 687–702. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2017.02.009

- Krisjanous, J. (2016). An exploratory multimodal discourse analysis of dark tourism websites: Communicating issues around contested sites. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 5(4), 341–350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2016.07.005

- Kuhzady, S., & Ghasemi, V. (2019). Pictorial analysis of the projected destination image: Portugal on instagram. Tourism Analysis, 24(1), 43–54. https://doi.org/10.3727/108354219X15458295631954

- Lian, T., & Yu, C. (2017). Representation of online image of tourist destination: A content analysis of huangshan. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 22(10), 1063–1082. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2017.1368678

- Li, J., Weng, G., & Pan, Y. (2021). Projected destination-country image in documentaries: Taking wild China and aerial China for example. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 20, 100609. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2021.100609

- Li, Y., Xu, X., Song, B., & He, H. (2020). Impact of short food videos on the tourist destination image—take Chengdu as an example. Sustainability, 12(17), 6739. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12176739

- Mariani, M. M., DiFelice, M., & Mura, M. (2016). Facebook as a destination marketing tool: Evidence from Italian regional destination management organizations. Tourism Management, 54, 321–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.12.008

- Marine-Roig, E., & Ferrer-Rosell, B. (2018). Measuring the gap between projected and perceived destination images of Catalonia using compositional analysis. Tourism Management, 68, 236–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2018.03.020

- McKee, A. (2003). Textual analysis: A beginner’s guide. Sage. http://digital.casalini.it/9781412932905

- Milman, A. (2012). Postcards as representation of a destination image: The case of Berlin. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 18(2), 157–170. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356766711435975

- Molina, A., Gómez, M., Lyon, A., Aranda, E., & Loibl, W. (2020). What content to post? Evaluating the effectiveness of Facebook communications in destinations. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 18, 100498. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2020.100498

- Morgan, N., Pritchard, A., & Piggott, R. (2002). New Zealand, 100% pure. The creation of a powerful niche destination brand. Journal of Brand Management, 9(4), 335–354. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.bm.2540082

- Morgan, N., Pritchard, A., & Piggott, R. (2003). Destination branding and the role of the stakeholders: The case of New Zealand. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 9(3), 285–299. https://doi.org/10.1177/135676670300900307

- Munir, K. A., & Phillips, N. (2005). The birth of the “kodak moment”: Institutional entrepreneurship and the adoption of new technologies. Organization Studies, 26(11), 1665–1687. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840605056395

- Noordin, W. N. W., Sukmayadi, V., & Wirakusuma, R. M. (2021). Projected destination image on instagram amidst a pandemic: A visual content analysis of Indonesian national DMO. In A. H. G. Kusumah, C. U. Abdullah, D. Turgarini, M. Ruhimat, O. Ridwanudin, & Y. Yuniawati (Eds.), Promoting creative tourism: Current issues in tourism research (1st ed., pp. 196–201). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781003095484-30

- Pan, X., Rasouli, S., & Timmermans, H. (2021). Investigating tourist destination choice: Effect of destination image from social network members. Tourism Management, 83, 104217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2020.104217

- Picazo, P., & Moreno-Gil, S. (2019). Analysis of the projected image of tourism destinations on photographs: A literature review to prepare for the future. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 25(1), 3–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356766717736350

- Pradhan, M. (2016). Travel photography: Destination workshop [ Bachelor’s thesis, Laurea University of Applied Sciences]. Laurea University of Applied Sciences Theses (Open collection). https://urn.fi/URN:NBN:fi:amk-201605198618

- Presenza, A., Sheehan, L., & Ritchie, J. B. (2005). Towards a model of the roles and activities of destination management organizations. Journal of Hospitality, Tourism, and Leisure Science, 3(1), 1–16.

- Rachman, S., Hamiru, H., Umanailo, M. C. B., Yulismayanti, Y., & Harziko, H. (2019). Semiotic analysis of indigenous fashion in the island of buru. International Journal of Scientific and Technology Research, 1(1), 1515–1519. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/fs6ar

- Ramakhrisnan, V. (2020). Why it’s important for brands to keep posting on social media during COVID-19. Falcon.IO. https://www.falcon.io/insights-hub/case-stories/cs-social-media-strategy/why-itsimportant-for-brands-to-keep-posting-on-social-media-during-covid-19/

- Roberts, C. (2013). Photography and China. Reaktion Books.

- Shakeela, A., & Weaver, D. (2016). The exploratory social-mediatized gaze: Reactions of virtual tourists to an inflammatory YouTube incident. Journal of Travel Research, 55(1), 113–124. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287514532369

- Shani, A., Chen, P. J., Wang, Y., & Hua, N. (2010). Testing the impact of a promotional video on destination image change: Application of China as a tourism destination. International Journal of Tourism Research, 12(2), 116–133. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.738

- Siyamiyan Gorji, A., Almeida-García, F., & Mercadé Melé, P. (2021). Analysis of the projected image of tourism destinations on photographs: The case of Iran on instagram. Anatolia, 34(2), 144–162. https://doi.org/10.1080/13032917.2021.2001665

- Souiden, N., Ladhari, R., & Chiadmi, N. E. (2017). Destination personality and destination image. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Management, 32, 54–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2017.04.003

- Stone, L. S., & Nyaupane, G. P. (2019). The tourist gaze: Domestic versus international tourists. Journal of Travel Research, 58(5), 877–891. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287518781890

- Sun, M., Ryan, C., & Pan, S. (2015). Using Chinese travel blogs to examine perceived destination image: The case of New Zealand. Journal of Travel Research, 54(4), 543–555. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287514522882

- Sun, W., Tang, S., & Liu, F. (2021). Examining perceived and projected destination image: A social media content analysis. Sustainability, 13(6), 3354. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063354

- Ting, I. L. S., & McKercher, B. (2016). The production of online travel photography. University of Massachusetts Amherst Scholar Works. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/ttra/2010/Visual/2/

- Tomaž, K., & Walanchalee, W. (2020). One does not simply … project a destination image within a participatory culture. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 18, 100494. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2020.100494

- Tseng, C., Wu, B., Morrison, A. M., Zhang, J., & Chen, Y. (2015). Travel blogs on China as a destination image formation agent: A qualitative analysis using leximancer. Tourism Management, 46, 347–358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2014.07.012

- Urry, J. (1990). The “consumption” of tourism. Sociology (Oxford), 24(1), 23–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038590024001004

- Urry, J., & Larsen, J. (2011). The tourist gaze 3.0. SAGE Publications. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/waikato/detail.action?docID=786870

- Wang, A. (2022). Cultural implication and semantic opaqueness of color expressions in Chinese classics. An Interdisciplinary Journal of Literary Studies, 7(i), 168–181. http://postscriptum.co.in/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/pS7.iAiqing.pdf

- Xiao, X., Fang, C., & Lin, H. (2020). Characterizing tourism destination image using photos’ visual content. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 9(12), 730. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi9120730

- Xu, W. S. (2017). The origin and significance of the twenty-four solar terms in China. Contemporary Social Sciences, 2017(6), 33–44. https://css.researchcommons.org/journal/vol2017/iss6/4

- Xu, M., Kim, S., & Reijnders, S. (2020). From food to feet: Analysing a bite of China as food-based destination image. Tourist Studies, 20(2), 145–165. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468797619888305

- Yang, S. (2019). Aesthetics of food: The role of visual framing strategies for influence building on instagram [ Master’s thesis]. Rochester Institute of Technology. ProQuest. https://www.proquest.com/openview/792f8531d1b5d45a0320bbc010d894b8/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y

- Zhang, D. (2009). On a synthetic theoretical framework for multimodal discourse analysis. Foreign Languages in China, 6(1), 24–30.

- Zhao, Z., Zhu, M., & Hao, X. (2018). Share the gaze: Representation of destination image on the Chinese social platform WeChat moments. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 35(6), 726–739. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2018.1432449