Abstract

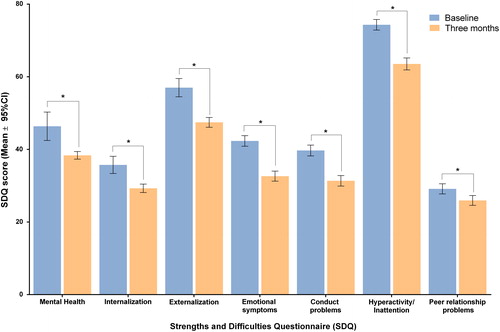

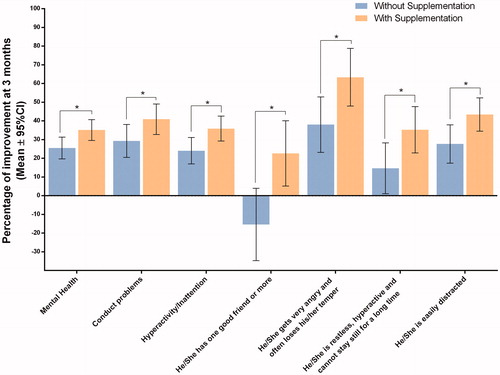

The aim of this study was to assess the impact of omega-3 fatty acid supplementation among other nonpharmacological treatments on mental health and quality of life (QOL) of children with behavioral disorders. An observational multicenter study of 6- to 12-year-old children with behavior-related problems was performed in Spain with a three-month follow-up assessment. The Kidscreen-10 and Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaires (SDQ) were used to assess effectiveness of each intervention. Characteristics of study population were compared with those of the general population. Subanalyses of two homogenous subgroups, who received versus did not receive dietary supplementation with omega-3 fatty acids, were performed. The study included 942 children (69.1% male) with a mean (SD) age of 8.5 (1.8) years. Overall, patients’ health status and QOL significantly improved at three months (p < .001). Scores on the SDQ also improved, with significant reductions on all subscales (p < .05). Comparison of SDQ results with the same-age general population showed higher overall scores in the study population (8.5 [5.5] vs. 18.6 [8.1], respectively) and on all the subscales (p < .001 in all cases). The omega-3 fatty acid supplementation subgroup presented greater improvements in each category of SDQ (p < .05), except for the emotion subscale. Omega-3 fatty acid supplementation alone or in combination with other nonpharmacological treatments is effective in improving children’s mental health. Overall, nonpharmacological recommendations currently made by pediatricians seem to be effective in improving the perceived health status and patients’ QOL and in the reduction of health problems, especially hyperactivity/inattention and conduct problems.

Introduction

The care and education of children with challenging behavior is an important concern both for parents and for the educational community (NCSE Citation2012). During childhood, this behavior arises from severe emotional disturbance/behavioral disorders and comprises many forms of specific learning difficulties such as dyslexia, developmental language disorders, and dyspraxia (Richardson Citation2006). Behavioral disorders arise from a host of factors that can cause emotional disturbance, stress, irritability/aggressiveness, insomnia, and other problems that negatively affect children’s engagement with school, making it difficult to fulfill their own individual potential (Gutman and Vorhaus Citation2012; NCSE Citation2012).

According to the published literature, behavioral disorders may affect 10%–20% of Spanish school-aged children (Fonseca-Pedrero et al. Citation2011). The finding that these disorders are more common in males and children with family history suggests a strong genetic base (Foster Citation2010). A wide range of studies have discussed psychosocial treatments (Kazdin Citation1997) and recommendations for educational professionals (Service Children’s Education Citation2015), focused mainly on psychological aspects; many other studies have linked different behavioral disorders with nutritional factors, stressing the relevance of the intake of polyunsaturated fatty acids (Curtis and Patel Citation2008; Kidd Citation2007) and minerals such as magnesium or zinc (Huss et al. Citation2010).

During recent years, researchers have investigated dietary omega-3 fatty acid supplementation as a nonpharmacological measure to address conduct disorders in children. The data accumulated so far show some evidence of significant improvements in behavioral disorders (Bloch and Qawasmi Citation2011; Gillies et al. Citation2012; Sonuga-Barke et al. Citation2013,) and tasks such as reading and spelling in groups receiving supplementation in comparison with controls (Richardson and Montgomery Citation2005). The effects of other nonpharmacological treatments such as behavioral interventions or neurofeedback are still not completely clear, although favorable results have been reported by the European ADHD Guidelines Group (Sonuga-Barke et al. Citation2013).

Therefore, investigating the different factors involved and their influence on behavioral disorders (Costello et al. Citation1988) and the effect of common recommendations made by pediatricians (Sonuga-Barke et al. Citation2013) and their impact either individually or in combination can help to define a proper guide for managing and redressing challenging behaviors in school-aged children, even in those without psychopathological diagnoses.

The aim of this study was to assess the impact of omega-3 fatty acid supplementation among other nonpharmacological treatments on the mental health and quality of life (QOL) of children with behavioral disorders.

Patients and methods

An observational multicenter nonrandomized study was performed from April 2014 to March 2015. The study included 6- to 12-year-old children with behavior-related problems and with no previous diagnosis of any psychiatric disorder that attended a pediatric clinic with an accompanying adult. Patients with psychiatric diagnoses (DSM-IV criteria) (APA Citation1995) at baseline were excluded. All the study materials were approved by the Clinical Research Ethical Committee of the Sant Joan de Déu Foundation of Barcelona, Spain. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and with good clinical practice guidelines. Informed written consent was obtained from all participants prior to enrollment.

Data collection and follow-up

Pediatricians recorded data at baseline and at three-month follow-up visit, including age, gender, anthropometric measures, alimentary patterns, rest time, health in the past 12 months, and other related factors to establish a patient profile. Health status was defined by a 5-point category scale ranging from 1 = “very poor” to 5 = “very good”. Nonpharmacological recommendations such as “referral to the psychologist,” “change of habits” (physical activity, sleep hygiene, cognitive-behavioral measures and dietary recommendations), “dietary supplementation,” and “general educational advice” provided by pediatricians not specialized in mental health, and other caregiver actions were recorded to reflect the routine medical praxis in these cases.

The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) (Goodman Citation1997) was used to assess the effectiveness of each intervention, presented as the improvement on this evaluation. The SDQ investigates 25 attributes, some positive and others negative, divided among five scales: emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity/inattention, peer relationship problems, and prosocial behavior. Higher SDQ scores indicate more difficulties. By grouping the emotional symptoms and peer relationship problems scales, we obtained a new category named internalization problems, and by grouping the scales of hyperactivity/inattention and conduct problems we obtained the externalization problems category. We labeled global SDQ score as mental health problems. For the visual presentation of the SDQ results, we presented it in a 100-point scale system. In this case, global SDQ score (range 0–40) has been multiplied by 2.5, Internalization/Externalization problems (range 0–20) has been multiplied by 5, and the five subscales (range 0–10) have been multiplied by 10.

With the aim of contextualizing the behavioral problems of the study population, its characteristics were compared with those of the general population of the same age recorded in the most recent National Health Survey (NHS) performed by the Spanish Statistics Institute in 2011, using z scores for each variable. To assess patients’ evolution during the study, cases with both baseline and three-month follow-up visits were compared. In addition, the percentile 80 of the NHS population regarding the SDQ score for each subscale (Fajardo et al. Citation2012) was used as a cutoff point to define the variable of normalization of SDQ score, obtaining a dichotomous variable. Below this cutoff point, children were considered to have an SDQ score contingent on their age. Children’s quality of life was assessed by the Kidscreen-10 questionnaire, on which higher scores indicate better levels of QOL.

At the three-month follow-up, we performed a subanalysis between two large homogenous subgroups created according to the dietary recommendations made by their pediatricians. The first cohort (n = 315) comprised children who received dietary supplementation with omega-3 fatty acids (EPA 520 mg, 315 mg DHA and omega-6, 60 mg GLA, 6 mg vitamin E, and 5 mg vitamin D; OmegaKids). The second cohort (n = 306) comprised children without supplementary recommendations.

Statistical analysis

The descriptive data presented include the mean, standard deviation (SD), and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). The relationship between categorical variables was analyzed using the chi-squared test or Mann-Whitney U tests, while continuous variables between visits were compared with the one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests. Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% CI were used to assess the differences between proportions. All inferences were performed with Windows SPSS statistics v22.0.

Results

Baseline data

The study included 942 children (69.1% male) with a mean (SD) age of 8.5 (1.8) years. Parents reported different kinds of behavioral disorders, with an estimated mean duration of 36.7 (31.3) months. Conduct problems (37.0%) and Inattention (34.4%) were the main reasons for consultation (). Children in the study were significantly smaller and thinner than the general population recording by the NHS; they also had shorter rest time and poorer health status over the past 12 months. Regarding dietary habits, we observed that scores on particular food groups varied, but overall, it could not be stated that either group was receiving a better diet. However, it should be stressed that fish intake was lower in the study group (p < .05) ().

Table 1. Main reasons for consultation.

Table 2. Comparison between EPOCA’s study baseline data and NHS population.

The study population showed significantly higher scores (i.e. more health problems) compared with the NHS sample on overall SDQ (18.6 [8.1] vs. 8.5 [5.5], respectively) and on all the subscales (p < .001 in all cases). Externalization items such as hyperactivity/inattention and conduct problems made notable contributions to the overall SDQ score (). The study group had significantly lower QOL than the NHS population (67.8 [12.0] vs. 87.9 [11.6]; p < .001).

Pediatricians’ praxis and follow-up

Dietary supplementation, either alone or in combination with other treatments, was the most frequent intervention at baseline (44.7%), followed by “general educational advice” (36.5%), “referral to psychologist” (31.9%), and “change of habits” (29.3%). Considering the measures in isolation, “general educational advice” was the preferred option (36.5%), followed by “dietary supplementation” (16.1%). Matching the baseline data from pediatricians with data on the compliance with recommendations reported by parents at three months, we observed that 60.3% of patients received nutritional supplementation and 92.0% presented good adherence. From baseline to the end of follow-up, 7.4% of patients were diagnosed with some kind of mental disorder and 13.5% of the whole study population were finally referred to a specialist. In the cases in which parents specified the type of specialist, 53.6% of patients consulted a child psychologist, 21.4% a child psychiatrist, and 17.0% a child neurologist. At the end of follow-up, only a small part of the study population (8.0%) were receiving pharmacological therapy.

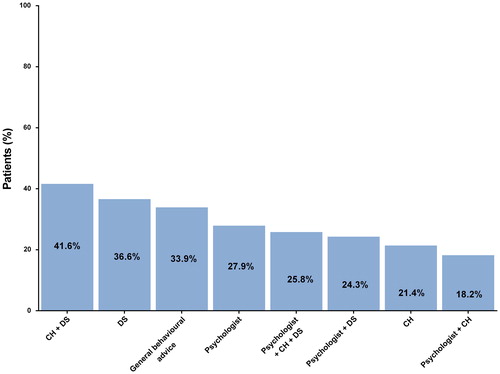

Three-month follow-up outcomes

Overall, patients’ health status improved significantly during follow-up, from a baseline score on the 5-point category scale of 4.09 (0.68) to a score of 4.31 (0.63) at three months (p < .001). QOL improved notably, to 73.6 (10.3) on the Kidscreen-10 questionnaire (+8.7% from baseline). Patients also had improved scores on the SDQ, with significant reductions on all subscales (p < .05). Specifically, the mean score for “mental health problems” fell to 15.3 (6.1) (p < .001), mainly due to a drop in externalization categories such as hyperactivity (). Regarding the impact of pediatricians’ recommendations on the SDQ results, the combination of “change of habits + dietary supplementation” obtained the best outcomes in terms of the “normalization” rate (41.6%), followed by dietary supplementation alone (36.6%) (). Mean rest time also increased by 11.4 minutes, from 9 to 9.19 hours at three-month follow up (p < .001), but it was not possible to attribute this result to a particular recommendation pattern. At the last visit, we observed a significant decrease in attending pediatrician’s or specialist’s consultations within the past four weeks (45.6% vs. 24.5%; p < .001).

Subanalysis of the two homogenous subgroups (dietary supplementation vs. no dietary supplementation)

To assess the strength of the main recommendations on patients’ mental health and QOL improvement, we performed a comparison of the two larger and homogenous study subgroups: one who received dietary supplement and the other who did not (). The group with dietary supplementation with omega-3 fatty acids achieved significantly better scores with regard to their mental health since many children presented improved scores on all categories of the SDQ scale (p < .05), except for the emotion subscale (). Furthermore, the mean improvement on some items and domains significantly favored the use of dietary supplementation (). Patients with dietary supplementation with omega-3 fatty acids were more likely to rest more than 9 hours (40.1% vs. 32.2%; OR [95% CI] = 1.41 [1.01, 1.96]; p = .041).

Figure 3. Comparison in SDQ scores between dietary supplementation vs. no dietary supplementation groups. Footnote to figure: CH change of habits, DS dietary supplementation.

Table 3. Homogeneity of the two subgroups of analysis.

Table 4. Percentage of children with improvement in each category of SDQ.

Discussion

Most of our patients who adhered to the nonpharmacological recommendations made by their pediatricians presented improved health status and QOL and reduced health problems, especially related with externalization, such as hyperactivity/inattention and conduct problems. Specifically, patients who received dietary supplementation in combination with other recommendations presented better scores than other combined interventions.

Importantly, the group with omega-3 fatty acids supplementation achieved better outcomes in mental health evaluation, and this improvement was higher in externalization domain. The increase in rest time beyond 9 hours in the dietary supplementation group supports the idea that improvements in behavioral disorders lead to improvements in other health-related conditions.

Prior studies designed to evaluate the effectiveness of omega-3 fatty acids in behavioral disorders have drawn similar conclusions. The randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group trial by Raine et al. (Citation2015) provided initial evidence that omega-3 supplementation can produce sustained reductions in externalizing and internalizing behavioral problems. A systematic review and meta-analysis of nonpharmacological interventions for attention deficiency hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) concluded that this type of supplementation achieves significant improvement, although its clinical significance has to be determined (Sonuga-Barke et al. Citation2013). The meta-analysis by Gillies et al. (Citation2012) also found that polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation obtained a small reduction in symptoms in children with ADHD.

Furthermore, the overall improvements in health status and rest time highlight the variety of factors that are interrelated in behavioral disorders. The increase in rest time observed in the study was a notable finding, particularly given that treated and untreated children with certain behavioral disorders display more sleep problems than their typically developing peers (Kirov and Brand Citation2014). For example, a meta-analysis found that children with ADHD, the most common neurobehavioral disorder of childhood (AAP Citation2000), experience more sleep difficulties than children without ADHD, including insomnia, sleep-disordered breathing, and circadian rhythm disturbances (Cortese et al. Citation2013; Um et al. Citation2017).

Our comparison of children included in the study with children from the general population demonstrated that behavior-related problems have a negative effect on children’s mental health and their QOL. In the management of these cases, specialists usually recommend dietary supplementation, either alone or in combination with other measures. Nonetheless, in many cases, no specific action is advised. Our data suggest a particular physical profile for children with behavioral disorders, as they tend to be smaller and thinner than the general population; but they do not seem to present a particular dietary pattern, at least not overall.

One limitation of our study lies in the difficulty of restricting the study population to children without pathological mental disorders. In fact, some of the patients included were receiving pharmacological treatment at the end of follow-up; this is to be expected, since the boundary between behavioral problems and more severe disorders is often blurred. In addition, we do not know exactly how parents apply the pediatricians’ recommendations or whether they introduce additional suggestions of their own (for example, in “change of habits”). Therefore, comparisons between types of recommendations should be interpreted cautiously.

It should be stressed that pediatricians have many options available in their daily clinical practice for managing behavioral problems in children. Very often, however, no specific advice is given, so we can assume that the behavioral problems of these children, or the impact of these problems on their health status, may easily be underestimated in a routine visit. For this reason, there is a need to consider other indicators to identify these patients who do not present pathological mental disorders but might benefit from additional nonpharmacological recommendations.

Further studies are required to better identify the unique characteristics of these patients. A detailed evaluation of the effectiveness of each set of recommendations (alone or in combination) would be interesting, ideally to be performed over a longer follow-up period.

Conclusions

Omega-3 fatty acid supplementation alone or in combination with other nonpharmacological treatments is effective in improving children’s mental health. Compared with the general population, behavioral disorders have a significant impact on children’s mental health and their QOL, even when these disorders do not reach pathological levels. Overall, the nonpharmacological recommendations currently made by pediatricians seem to be effective in improving the patients’ perceived health status and QOL and in reducing health problems, especially related with externalization, such as hyperactivity. Therefore, these recommendations may need to be established as part of clinical practice.

Declaration of interest

SO is a full-time employee of Laboratorios Ordesa S.L. The other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

About the authors

Pedro Javier Rodríguez-Hernandez, PhD (Psychology and Medicine), Psychologist in the Day Hospital for children and young Diego Matías Guigou y Costa, Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Unit, Candelaria University Hospital, Tenerife, Spain.

Alejandro Canals-Baeza, MD, PhD, Specialist in Pediatric Gastroenterology. Member of the SEGHNP. Pediatrician in CS Alicante-Sta Faz, Pediatrics Department, Hospital de San Juan, Alicante, Spain.

Alicia Santamaría-Orleans, PhD (Food Technology and Nutrition), MSc (Scientific Communication and Phytotherapy), Scientific Marketing Manager in Laboratorios Ordesa S.L., Barcelona, Spain.

Ferran Cachadiña-Domenech, MD, Specialist in Pediatrics and Quality Healthcare, Director of Pediatrics and Quality Healthcare in Fundació Hospital de Nens, Barcelona, Spain.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the pediatricians who contributed to the collection of data.

Funding

The present study was funded by Laboratorios Ordesa S.A.

References

- American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP). 2000. Committee on Quality Improvement and Subcommittee on Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 105:1158–1170.

- American Psychiatric Association (APA). 1995. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV. 4th ed. Washington (DC): American Psychiatric Association.

- Bloch MH, Qawasmi A. 2011. Omega-3 fatty acid supplementation for the treatment of children with attention-Deficiency/hyperactivity disorder symptomatology: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 50(10):991–1000.

- Cortese S, Brown TE, Corkum P, Gruber R, O'Brien LM, Stein M, Weiss M, Owens J. 2013. Assessment and management of sleep problems in youths with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 52(8):784–796.

- Costello EJ, Costello AJ, Edelbrock C, Burns BJ, Dulcan MK, Brent D, Janiszewski S. 1988. Psychiatric disorders in pediatric primary care. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 45(12):1107–1016.

- Curtis LT, Patel K. 2008. Nutritional and environmental approaches to preventing and treating autism and Attention Deficiency hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): a review. J Altern Complement Med. 14(1):79–85.

- Fajardo F, León B, Felipe E, Ribeiro EJ. 2012. Mental health in the age group 4–15 years based on the results of the national survey of health 2006, Spain. Rev Esp Salud Publica. 86(4):445–451.

- Fonseca-Pedrero E, Paino M, Lemos-Giráldez S, Muñiz J. 2011. Prevalence of emotional and behavioral symptoms in Spanish adolescents using the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ). RPPC. 16(1):17–25.

- Foster J. 2010. El niño con problemas de conducta y/o aprendizaje escolar. Boletín Especial Sociedad de Psiquiatría y Neurología de la Infancia y Adolescencia. [accessed 2016 July 25]. http://escuela.med.puc.cl/paginas/publicaciones/manualped/probcond.html.

- Gillies D, Sinn JKH, Lad SS, Leach MJ, Ross MJ. 2012. Polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) for attention Deficiency hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 11(7):CD007986.

- Goodman R. 1997. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: a research note. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 38(5):581–586.

- Gutman LM, Vorhaus J. 2012. The impact of pupil behaviour and wellbeing on educational outcomes. London (UK): Childhood Wellbeing Research Centre, Institute of Education, University of London..

- Huss M, Völp A, Stauss-Grabo M. 2010. Supplementation of polyunsaturated fatty acids, magnesium and zinc in children seeking medical advice for attention-Deficiency/hyperactivity problems - an observational cohort study. Lipids Health Dis. 9(1):105.

- Kazdin AE. 1997. Practitioner review: psychosocial treatments for conduct disorder in children. J Child Psychol Psychial. 38(2):161–178.

- Kidd PM. 2007. Omega-3 DHA and EPA for cognition, behavior, and mood: clinical findings and structural-functional synergies with cell membrane phospholipids. Altern Med Rev. 12(3):207–227.

- Kirov R, Brand S. 2014. Sleep problems and their effect in ADHD. Expert Rev Neurother. 14(3):287–299.

- National Council for Special Education (NCSE). 2012. The Education of Students with Challenging Behaviour arising from Severe Emotional Disturbance/Behavioural Disorders. NCSE Policy Advice n° 3.

- National Institute of Statistics (Spain) 2011. National Health Survey. [accessed 2016 July 25]. http://www.ine.es/inebmenu/mnu_salud.htm.

- Raine A, Portnoy J, Liu J, Mahoomed T, Hibbeln JR. 2015. Reduction in behavior problems with omega-3 supplementation in children aged 8-16 years: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, stratified, parallel-group trial. J Child Psychol Psychiatr. 56(5):509–520.

- Richardson AJ, Montgomery P. 2005. The Oxford-Durham study: a randomized, controlled trial of dietary supplementation with fatty acids in children with developmental coordination disorder. Pediatrics. 115(5):1360–1366.

- Richardson AJ. 2006. Omega-3 fatty acids in ADHD and related neurodevelopmental disorders. Int Rev Psychiatry. 18(2):155–172.

- Service Children’s Education (SCE). 2015. Guidance – Managing Challenging Behaviour. [accessed 2016 July 25]. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/339074/Managing_Challenging_Behaviour_Final-U.pdf.

- Sonuga-Barke EJS, Brandeis D, Cortese S, Daley D, Ferrin M, Holtmann M, Stevenson J, Danckaerts M, van der Oord S, Döpfner M, European ADHD Guidelines Group, et al. 2013. Nonpharmacological Interventions for ADHD: Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses of Randomized Controlled Trials of Dietary and Psychological Treatments. Am J Psychiatry. 170(3):275–289.

- Um YH, Hong SC, Jeong JH. 2017. Sleep problems as predictors in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: causal mechanisms, consequences and treatment. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 15(1):9–18.