ABSTRACT

Public discourse about climate change is characterized by a wide variety of frames. Understanding how people integrate climate change narratives into their lives is essential for designing socially accepted climate policies. Our study focuses on people’s positions and reactions concerning the effects of sea level rise on the Catalan coast (Spain) and references tweets related to a 2021 publication by Climate Central, Picturing Our Future, on sea level rise. The novelty of the approach is the focus on a gradual form of climate change, such as sea level rise, in contrast with extreme events, such as storms or heat waves. We collected and analysed the content of 287 tweets that reacted to the Climate Central’s publication mentioned above, classifying them in terms of the sentiment they expressed. The results show three main types of reactions: realist, joking, and denier. Our conclusions underscores the significance of attending to how climate change narratives are portrayed and communicated through social media, and how societal beliefs and perspectives shape these narratives and dispositions. These aspects, crucial for fostering awareness and concern about pressing environmental issues, accentuate the necessity of integrating them into climate policy design.

1. Introduction

In the current Anthropocene era, climate change has become an illustration of the collective relationship that human beings have with nature. Climate models predict scenarios characterized by an escalation in the intensity and frequency of extreme phenomena resulting from human activity. These include elevated surface temperatures, an escalating number of heatwaves, and prolonged periods of drought (IPCC Citation2021). To some extent, these extreme phenomena have already become evident in the first decades of the 21st century, and they are anticipated to persistently escalate. Furthermore, an expanding number of individuals are experiencing these climate change-related phenomena, which are compelling them to migrate (Roxburgh et al. Citation2019; IPCC Citation2021).

At present, climate change is a topic of growing discussion in the context of global science and politics, and the frequency of this topic in public debate and the popular and collective consciousness is also increasing. Beyond being solely a scientific and environmental concern, climate change is an inherently societal issue with consequential impacts on political, social, and economic contexts (Boykoff and Pearman Citation2019).

Despite broad scientific consensus concerning the causes of climate change (Williams et al. Citation2015), public discourse related to climate change is characterized by a wide variety of perspectives, beliefs, and understandings that emphasize the common polarized positions of believers and deniers (Whitmarsh Citation2011; Weber Citation2016). Mostly, climate change is simplified by a focus on more visible and tangible events, such as floods, heat waves, and hurricanes, i.e. extreme events or natural disasters that we can perceive and experience directly, which are also events that we are increasingly used to seeing depicted on mass media.

An increasing number of people continually use social media sites to inform others of and express their beliefs and concerns regarding environmental, natural conservation, and climate change issues (Pearce et al. Citation2019). These social media networks are gaining importance as platforms on which people can freely share their opinions with other people, using virtual spaces to prompt discussion and debate (Pickering and Norman Citation2020). Numerous studies (Hamed et al. Citation2015; Pearce et al. Citation2019; Wei et al. Citation2021) have noted that some social media platforms, in particular Twitter, have increasingly become the focus of scientific attention with respect to the analysis of individual and collective opinions and views. Several studies have highlighted the importance of using social media as a source of information to explore perceptions, beliefs, and understandings regarding climate change as well as the factors that can influence and shape such views (Tamburrini et al. Citation2015; Pearce et al. Citation2019).

Social media have the power to narrow or broaden the focus of attention regarding certain environmental or political issues and support or impede certain interactions between science and society (Cody et al. Citation2015; Jang and Hart Citation2015; O’Neill et al. Citation2015). In this sense, improving our understanding of the ways in which people perceive, pay attention to, and integrate climate change discourse into their lives and actions is of paramount importance (Weber Citation2016). These aspects are crucial to reduce the disparity between science and society and to implement environmental policies that can receive broad social acceptance, being capable of inspiring consciences to seek out effective and communal transformative solutions (Boykoff and Pearman Citation2019).

To date, few studies have focused on analysing people’s perceptions and public frames regarding slower and more gradual events, such as the phenomenon of sea level rise, which is often perceived to be distant both spatially and temporally (Retchless Citation2018; Boykoff and Pearman Citation2019). To fill this research gap, our study focuses on exploring people’s perceptions, beliefs, and understanding regarding this slower and more “intangible-gradual” form of climate change.

We focus on the sea level rise occurring on the Catalan coast (along the northwest Mediterranean), which we use as a case study area by examining tweets related to research published by Climate Central in 2021 (Climate Central Citation2021) and reported by several local and regional media. Climate Central is an independent group of scientists who aim to communicate scientific topics about climate change in an understandable way, using storytelling and visual models to bring people closer to climate change and raise awareness and concern about this phenomenon. In this research, we use the Climate Central “Picturing Our Future” publication, which illustrates the potential future impacts of sea level rise using visual tools such as maps. The study shows coastal areas that may be subject to flooding and compares the outcomes of sea level rise in the contexts of global warming scenarios featuring 1.5° and 3.0° increases in temperature. These predictions are visually depicted through the use of maps, specifically highlighting coastal areas at risk of flooding. Our decision to concentrate on this study is attributed to its extensive media coverage, making it a valuable opportunity to explore social perceptions concerning sea level rise within the study area.

Using the reactions to this research published on Twitter©, the purpose of our study is twofold: i) to analyse what kinds of beliefs, perceptions, and reactions people exhibit in response to a slower and more gradual form of climate change, such as sea level rise; and ii) to understand the importance and implications of social media with respect to framing public beliefs and understandings regarding climate change, as well as the importance of social media with respect to informing and transferring scientific knowledge for raising awareness and concern about urgent environmental topics. In this study, when we use the terms perceptions, beliefs or reactions, we are referring to how people understand a determinate argument or discourse (Vikström et al. Citation2023), assuming specific attitudes and positions can be framed into different narratives.

Understanding the position of citizens regarding a given topic has direct implications for the design of environmental, social, and economic policies that can affect individuals’ consciences, with the purpose of establishing collective awareness based on shared information and addressing the important socioecological challenges that we are currently facing.

2. Methods

2.1. Description of study area

Our study focuses on the Catalan coast, which is located on the northeastern coast of the Iberian Peninsula along the northwestern Mediterranean. The Catalan coast is one of the most attractive tourist destinations in Europe (Pueyo-Ros et al. Citation2018). This region relies on various urban tourist attractions along the coast and on recognized coastal wetlands, which are well known for their important ecological and recreational value (Pueyo-Ros et al. Citation2018). Likewise, there are important urban locations along the coast, with Barcelona being the most important such location (3.2 million inhabitants). Overall, coastal municipalities are home to 43% of the Catalan population (Garcia-Lozano et al. Citation2018). Climate scenarios predict changes in the availability of water, suffering pressures derived from and exacerbated by the effects of climate change, especially in relation to decreased rainfall, increased temperatures and prolonged periods of drought (Ryan et al. Citation2011; Loizidou et al. Citation2016; Cramer et al. Citation2018), which translates into a progressive increase in social problems for the use of environmental resources.

Despite the growing concern about the impacts of climate change in the Mediterranean, public opinions on climate change are polarized. Regarding the public perceptions on climate change on the Catalan coast, for example, the positions of people about how climate change might affect different sectors are divided. Previous research in the same study area has shown that the tourism sector, one of the main economic activities (Jiménez et al. Citation2017), is divided into those who see climate change as an opportunity to lengthen the tourist season and those who see it as a threat to tourism, especially in relation to the uncertain availability of water and the restrictions on its use in the high tourist season (Gabarda-Mallorquí et al. Citation2018; Torres-Bagur et al. Citation2019).

Sea level rise is predicted to have significant impacts throughout the Mediterranean basin (Loizidou et al. Citation2016), especially with respect to its possible impacts on coastal urban areas (Covi and Kain Citation2016; Benjamin et al. Citation2017), beach sediment erosion, and coastal ecosystem services (Casas-Prat and Sierra Citation2012; Jiménez et al. Citation2017), as is the case for the Catalan coast.

For all these reasons, the study on sea level rise published by Climate Central (Climate Central Citation2021) has been echoed by several and regional local media and had a broad impact on Twitter Catalunya, where most of the population is concentrated in the coastal areas (Jiménez et al. Citation2017). The “Picturing our future” publication demonstrates, through the use of visual maps, how distinct areas of the Catalan coast may be subject to flooding depending on the global warming scenario under consideration (i.e. 1.5° or 3.0°). For these reasons, we considered the Catalan coast to represent a key opportunity to study the perceptions, beliefs and positions of people in relation to a slower form of climate change as sea level rise.

2.2. Data collection

The information used in this study was collected by selecting all the tweets and their replies that reacted to an October 2021 research publication by Climate Central. The selection of tweets was performed via a Twitter search using the keywords (in parenthesis the translation to English when the keyword was in Catalan): “Climate Central”, “augment del nivell del mar” (sea level rise), “nivell del mar” (sea level), and “canvi climàtic” (climate change). Tweets collected were posted between October 2021, the study’s date of publication, and December 2021, the date on which the data collection was conducted. We included only tweets that referred to the study by Climate Central and contained a study map, which showed the areas that may be subject to flooding. We focused on the tweets that included a map of the Climate Central publication of sea level rise to evaluate whether the tweet and its subsequent replies departed from the visual information provided by the map. Although we used Catalan keywords, the results of the search also included Spanish tweets (mainly replies), so we decided to include Catalan and Spanish tweets in the analysis.

Applying the selection criteria, we collected 287 tweets. In addition to the text of the tweets, we gathered the following metadata: the date of publication, the type of tweet (direct, reply or reply to reply), and the presence of emoticons, images, gifs or URLs in the tweet. To produce a list of potential types of reactions, we identified categories based on the literature exploring people’s perceptions and beliefs concerning climate change, particularly the study by (O’Neill et al. Citation2015). That study illustrated several frames employed in climate change discourse and defined the process of constructing such a frame as follows: “select some aspects of a perceived reality and make them more salient in a communicating text, in such a way as to promote a particular problem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation, and/or treatment recommendation” (Entman Citation1993; O’Neill et al. Citation2015). Adapting the distinct characteristics of each category from O’ Neill’s study, we used them as a starting point with the intention of exploring the frames and positions that people could assume in relation to sea level rise.

Previous studies have shown that there are several factors, including psychological, sociological, and cultural factors, that can affect and shape people’s perceptions and beliefs on climate change (Cody et al. Citation2015; O’Neill et al. Citation2015; Burger et al. Citation2016; Weber Citation2016). Some of these factors relate to the different experiences we are able to have with climate change, including geographic distance from climatic events such as natural disasters, the occurrence of such events over a short-term or long-term period, and the types of climate effects to which we are exposed (Retchless Citation2018). People who have a direct effect of climate change, such as a flood or a hurricane, exhibit a learning-from-experience process (Weber Citation2010), which means that they are more likely to believe in the effects of climate change and to exhibit a greater willingness to engage in pro-environmental behaviours. This phenomenon could be explained by the fact that such individuals “turn experienced adverse aspects of the environment into feelings of fear, dread, or anxiety, which then influence decisions” (Weber Citation2010). In contrast, although this could vary across different countries and could be influenced by sociocultural or personal factors, people who have not experienced the effects of climate change personally tend to express denial or sceptical views, such as the belief that climate change is a slow and distant phenomenon that does not concern them or the belief that climate change is a political or economic invention with the aim of exerting power over the world (O’Neill and Boykoff Citation2010; Whitmarsh Citation2011). However, certain studies (e.g. Fincher et al., 2015) also indicate that even when individuals experience the impacts of climate change, such as frequent flooding, their ability to cope with such events leads them to believe in their resilience in the face of climate change. Other factors relate to value orientation, social identity, groups’ norms (Curnock et al. Citation2019), ideologies, world views (Jenkins-Smith et al. Citation2020), and political identities (Leviston et al. Citation2013) and can influence the construction of frames and positions on climate change.

Frames represent the ways in which people notice, understand and remember a problem and the manners in which they choose to act regarding that problem (Entman Citation1993). We used the model of categories proposed by O’Neill et al. (Citation2015) as a starting point for building our categories, modifying and adapting the definitions to our study objective. Especially, taking into account the type of reaction to sea level rise expressed in the analysed tweets and comparing it with the definitions of O’Neill categories. We produce 11 categories, which we used to classify the types of reactions people expressed in each tweet ().

Table 1. Description of the categories used to classify people’s reactions as expressed in their tweets. The categories were adapted from the study by O’Neill et al. (Citation2015).

2.3. Content analysis: classification of reactions

First, each tweet was classified independently by three different researchers based on the elaborated categories. shows the categories used for the first classification round and describes them in detail.

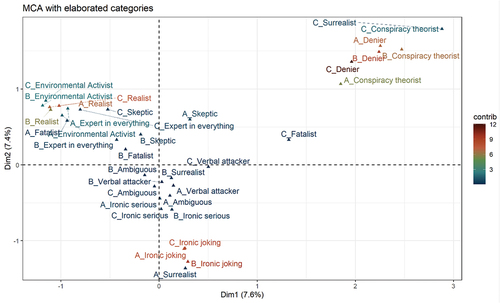

Subsequently, we calculated Fleiss’s kappa coefficient to estimate interrater agreement (Fleiss Citation1971) and the number of tweets for which at least two raters agreed on a category. To increase the robustness of the classification, we conducted a multiple correspondence analysis (MCA) to explore overlaps among these categories. Based on the MCA results, we divided the categories into four distinct groups that were visually discernible on the MCA plot and held conceptual significance. To address the tweets situated in the ambiguous zone, we employed a “stepwise” approach using Fleiss’ kappa coefficient as a measure of robustness. Essentially, we explored various combinations by incrementally adding or removing categories from the initial classification derived from the clustered groups, until achieving the optimal kappa coefficient.

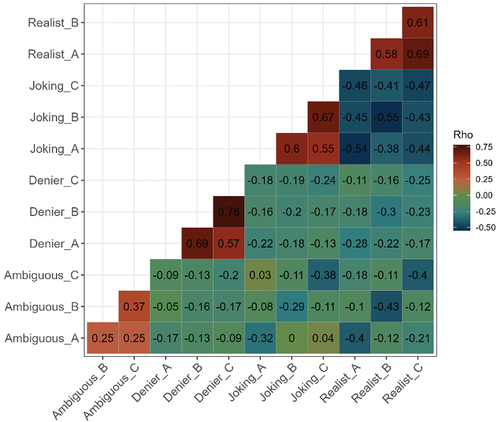

For these new categories, we calculated the degree of consensus based on the level of agreement among raters using three different methods. First, we estimated Fleiss’ Kappa coefficient; second, we calculated the number of tweets for at least two raters who agreed on a category, and last, we performed a correlation matrix among classifications of each reviewer to validate the new classifications. The correlation matrix should show strong correlations among the same categories across reviewers and weak or strong negative correlations among different categories. Finally, we performed a final classification of the tweets as follows. If two or more raters agreed on one category, the tweet was classified accordingly. If all three raters classified the tweet into three different categories, the tweet was classified as “no agreement”.

3. Results

3.1. Tweets related to “picturing our future” publication and definition of categories

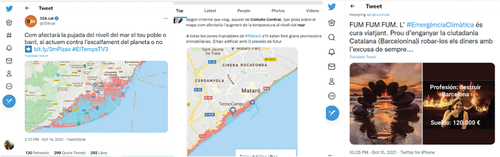

We collected 287 valid tweets in the Catalan and Spanish languages. All the selected tweets contained a map or at least a link related to the “Picturing our future” publication of Climate Central, or they were retweets or replies to tweets related to the Climate Central publication. Among these tweets, 9 were posted by organizations, mainly press and television, and the rest were posted by personal accounts. Regarding the type of reaction, 26 were direct tweets (level 1), 155 were replies to a direct tweet (level 2) and 106 were replies to replies (level 3) (doi: 10.5281/zenodo.6559169). shows examples of analysed tweets belonging to different categories.

Figure 1. Examples of tweets referring to the climate Central publication regarding sea level rise, including maps, links to research or gifs. Left: L1, first classification: realist, second classification: realist. Middle: L1, first classification: realist, second classification: realist. Right: L2, first classification: conspiracy theorist, second classification: denier.

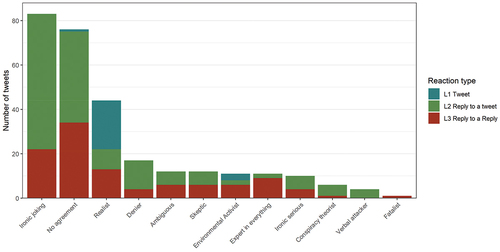

Following the first classification of categories extracted from the literature and adapted from (O’Neill et al. Citation2015), the agreement (Fleiss’ kappa) between raters had a value of 0.37 (p value < 0.05), and the number of tweets concerning which at least two raters agreed was 211 (73.5%). For this reason, tweets without agreement between the three raters were classified as “No agreement”. The most frequent reaction found was Ironic Joking, followed by Realist All level 1 tweets were classified as Realist or Environmental Activist ().

With respect to this initial classification, we performed a multiple correspondence analysis (MCA) to explore and represent any interrelationships between the different types of categories and focus on those relationships that can best help explain variations and diversity in the reactions of people ().

Figure 3. Multiple correspondence analysis of the elaborated categories as classified by three raters (A, B and C). The colour of the labels indicates the contribution made by that category to the first two dimensions.

In accordance with the MCA results, three groups were clearly distinguished, where some categories belonged clearly to one group, while others were located in a blurred zone. More specifically, the first two axes of the MCA accounted for 15% of the variability. The first axis (7.6%) was described by the relationship between the Denier and the Conspiracy theorist categories (in the positive values) and the Realist and Environmental Activist categories (in negative values). The second axis (7.4% of variability) was represented especially by the contrast between the Realist category (in the positive values) and the Ironic serious and joking categories.

At the end of the stepwise process, four groups of variables remained. One group contained the categories Realist, Expert in Everything, Environmental Activist, Fatalist and Sceptic (regarding policy), which we named the Realist group. A second category included the Conspiracy theorists and the Deniers; this category was called the Denier group. A third group contained only the Ironic joking category. Finally, we also identified a blurred zone in the middle of the MCA plot containing the following categories: Surrealist, Ironic serious, Ambiguous, and Verbal attacker; this set was called the Ambiguous group. Moreover, there was clear disagreement concerning tweets that were classified as Surrealist. Hence, we decided to include this category within the Ambiguous group as well.

The correlation matrix results (), calculated to validate the new classification of categories obtained with Fleiss’ Kappa coefficient and the MCA, confirmed a strong positive correlation among the same categories classified by the three raters and strong negative correlations among different categories. As expected, the three categories showed the highest positive values with themselves across raters. Moreover, the categories of Realists and Joking showed the highest negative correlation, showing little overlap across raters or within a specific rater.

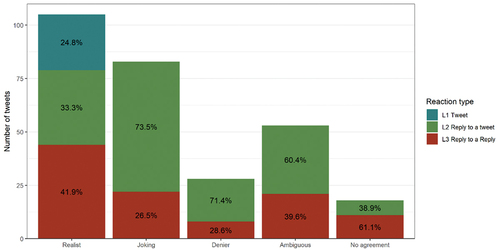

The new classification had an agreement value of 0.543 (p value < 0.05). The number of tweets concerning which at least two raters agreed was 268 (93.3%). Based on this new classification, the most frequent tweets were Realist, which was the only category to contain direct tweets. The second most frequent category of tweets was Joking ().

3.2. The diversity of narratives about sea level rise

We identified four clear primary consistent narratives: the Realists, who mostly believe that sea level rise is a phenomenon that is happening, demonstrated by scientific data and receiving insufficient attention from politicians; the Deniers, who believe that climate change is an invention and a strategy used by governments to frighten people; the Jokers, who exhibit sceptical behaviour, making jokes concerning the possible effects of sea level rise and imagining a humorous future; and the Ambiguous, who express ambiguous perceptions and beliefs, thereby making it difficult to classify their positions. These findings support the results reported by O’Neill & Boykoff (O’Neill and Boykoff Citation2010), which indicated that is frequently the case that people are primarily divided into “convinced” and “unconvinced” groups, as noted in our study but also that this division is not the only possible categorization in this context. Regarding climate change, people’s opinions exhibit myriad shades of narratives. contains examples of tweets showing different narratives depending on the category.

Table 2. Example of tweets showing different narratives in relation to sea level rise.

In our study, most tweets fell into the Realist category, which included Environmental activists, Experts in everything, Fatalists and Sceptics (regarding policy). The narratives expressed within this category aim to inform others regarding the possible effects of sea level rise, and the individuals making such claims base their affirmations on scientific data in support of their tweets.

We noticed one interesting aspect of these tweets, namely, the fact that this category is the only category to contain reaction type tweets of level 1 (L1, i.e. direct tweets), including maps, links and URLs affording direct access to the Climate Central publication or to scientific reports and articles related to climate change. The discourses and narratives expressed in the Realist category emphasize the fact that people whose tweets fit into this category tend to believe strongly in climate change, recognize the importance of scientific data and the urgent need to communicate with and inform others, and contribute to increasing people’s knowledge concerning and awareness of environmental issues and the possible effects of climate change.

The second most frequent category was the Joking category. In this context, people expressed perceptions and beliefs regarding the effects of sea level rise by using jokes and irony. In this way, they downplayed and ridiculed climate models that indicated areas that could be subject to flooding.

We detected an interesting relationship between the Joking and Realist categories; that is, tweets that were included in the Joking category always represented a reaction type of level 2 (L2, i.e. a reply to a tweet) or level 3 (L3, i.e. a reply to a reply) but never a reaction type of level 1 (L1, i.e. an original tweet). These results highlight the fact that Joking is almost always present in or intrudes into conversations concerning the possible effects of sea level rise, but the people who create such messages never start a new conversation or post a new tweet, just replying with jokes, sarcastic comments or emoticons that express irony.

The Denier category also followed this pattern, since messages in this category included only reaction types of levels 2 and 3 (i.e. replies to tweets or replies of replies). This category focused on a complete denial of the phenomenon of climate change in general, thereby including rejecting and contrary opinions, as noted by O’Neill & Boykoff (O’Neill and Boykoff Citation2010). In fact, narratives belonging to this category mainly perceive climate change as a lie that has been promulgated by politicians, the economic sector, and religions to frighten people and maintain control of society.

4. Discussion

4.1. A diversity of narratives shaped by people’s beliefs

Our results confirm that individuals interpret climate change discourse on social media by constructing distinct frames (O’Neill et al. Citation2015). These frames are shaped by people’s perceptions, understandings, and beliefs, influenced by various factors (Weber Citation2016; IPCC Citation2021). The different types of tweets we analysed resulted in distinct categories, each characterized by unique narratives. These categories can be compared with the “ten climate change issue” frames identified by O’Neill et al. (Citation2015), representing culturally available frames associated with the IPCC Fifth Assessment Report. Through this comparison, we can observe how the analysed tweet types correspond to specific profiles of individuals who engage in discussions and contribute to the shaping of climate change frames on social media. These profiles are influenced by specific internal and external factors, as explained by Weber & Stern (Citation2011a). For more in-depth information, refer to O’Neill et al. (Citation2015).

Messages in the Denier category exhibited a tendency to interpret and frame scientific predictions and climate change data as conspiracy theories or manifestations of a “big brother” philosophy, and the individuals who created such messages tended to view scientific research and information concerning climate change as corrupt and focused more on political views than scientific discourse, as noted by other studies (Whitmarsh Citation2011; Jacques and Knox Citation2016; Roxburgh et al. Citation2019).

Likewise, the “Joking” category presents an intriguing food for thought. Humour and irony are social mechanisms of response (Bovey and Hede Citation2001) and can sometimes serve as coping mechanisms for negative or surreal events. On one hand, adopting a sarcastic approach to communicate or internalize news about climate change can influence viewers’ perceptions, leading to an interpretation of the message as ambiguous and sceptical, thereby diminishing its significance (Brewer and McKnight Citation2015). On the other hand, humour and irony can be powerful tools for expressing serious emotions, concerns, and worries, aiding in the communication of complex environmental issues and engaging people in the understanding process (Ross and Rivers Citation2019; Lyytimäki Citation2021). Consequently, conducting a thorough analysis of these ironic tweets could provide insights into the underlying reasons for such humorous reactions. This behaviour is well reflected in the popular expression, “I laugh so as not to cry”.

4.2. Ideology and perception are more persistent than evidence and knowledge

Denial narratives based their opinions on ideology rather than evidence (Whitmarsh Citation2011). These findings are consistent with those of Whitmarsh (Citation2011), who noted that “public belief in (versus scepticism about) climate change is principally determined by knowledge (or lack of it) about the issue”. Knowledge and understanding tend to increase people’s levels of awareness regarding climate change facts (Burger et al. Citation2016), thereby increasing our motivation to act. Despite this, we emphasize that it is important to consider the various dimensions of knowledge for it to be used as a good driver of public perception about climate change (Shi et al. Citation2016).

These frames illustrate how identical information can be interpreted in various ways, contingent on individuals’ cognitive abilities, prior knowledge, mental models, and value systems (Whitmarsh Citation2011). We observed that one significant influencing factor is the type of experience people have with specific climate change effects and their ability to directly observe these effects (Whitmarsh Citation2008; Weber Citation2016; IPCC Citation2021). In the analysed tweets, we noticed a recurring theme regarding people’s difficulty in perceiving sea level rise as a tangible and ongoing effect, despite its projected significant impacts, particularly in coastal regions. The representation and visualization of these effects through maps, depicting areas susceptible to flooding, evoked distinct reactions among social media users. On one side, certain individual were well aware of the substantial societal consequences that flooding of coastal areas could entail, leading them to post tweets such as A and D in . On the other side, some individuals viewed this representation as exaggerated and surreal, expressing their opinions through tweets such as H, J, K, and L (refer to ).

Some phenomena that we do not experience directly, such as glacier melting or tsunamis, are mediated using more visible elements that we can comprehend, such as an image of a polar bear swimming between ice caps or people navigating by boat through the streets of flooded villages. However, more gradual and slower phenomena, such as sea level rise or greenhouse gas emissions, do not allow us to associate them with any “tangible and visible” element (Moser Citation2010). Therefore, all the graphical representations based on scientific models, born with the intention of explaining highly complex phenomena and processes in an intelligible and simple way and bringing people closer to these issues, such as the maps of areas that may be flooded, become ridiculous theories, not taken seriously and almost considered to represent surreal scenarios: “If I live at 1200 m, do I have to suffer or do I have time to build the ark calmly?”. For some people, social media is the only source of information that generates knowledge on a certain topic (Vikström et al. Citation2023). Therefore, how social media communicates, the images they produce, and the messages they transmit on a certain topic are highly sensitive to the interpretation of people, who create their own opinions based on information from social media. Moreover, the images that cause us to believe in climate change are not always rigorous. For instance, polar bears have always been known to swim between ice caps (Pilfold et al. Citation2017). A more rigorous but less sensational marketing campaign may have a more substantial impact on raising awareness (Swim and Bloodhart Citation2015).

Indeed, these discourses encompass a spectrum of reactions and positions that are influenced by both personal and external factors. As explained by Pidgeon (Citation2012), these are related to the difficulty of perceiving gradual and slow phenomena such as changes in sea level. Accordingly, the impossibility of experiencing these changes produces uncertainty and psychological distance (Moser Citation2010; Taylor et al. Citation2014) between the person and the phenomenon of sea level rise, which is reflected in critical beliefs and understandings that ridicule climate models and future climate scenarios presented by the scientific community. This phenomenon could be explained by the concept of “uncertainty transfer”: people’s uncertainty resulting from the difficulty of understanding complex phenomena generates further uncertainty in relation to the phenomenon itself, thus amplifying the lack of trust in the evidence explaining that phenomenon. Thus, often, scientific debates that pertain to uncertain phenomena, such as the risks or possible impacts of climate change, increase and reinforce people’s uncertainty, thereby causing greater disbelief in and scepticism concerning these issues (Pidgeon Citation2012). This situation explains the large number of people whose tweets express joking, ironic or completely denialist reactions to the flood maps.

Similarly, we observed the lack of information and knowledge concerning climate change in general and the difficulty of comprehending complex phenomena, as sea level change can act as “barrier factors”. This leads to a lack of information and knowledge concerning climate change in general. Both lead to such knowledge being replaced by sarcasm and irony as reaction mechanisms (Pearce et al. Citation2019).

4.3. Social media as discourse amplifiers

These findings also align with previous research, that has demonstrated that in the realm of social media, individuals tend to communicate and interact predominantly with others who share similar beliefs. We observed that deniers and jokers, despite replying to realists, do not engage in constructive discussions but rather they posted responses reinforcing their own beliefs and opinions. This phenomenon is commonly referred to as “echo chambers”, wherein the “chambers” represent the spaces for information sharing (in this case, tweets and the social media platform), and the “echo” arises from the continuous repetition of pre-existing beliefs, thereby magnifying confirmation bias (Jasny et al. Citation2015; Williams et al. Citation2015).

Nonetheless, social media have the power to influence people’s perception and feelings by amplifying discourses or facilitating communication regarding events resulting from climate change that relate to strong emotions (e.g. anger, opposition, discrimination, or support) (Weber and Stern Citation2011). This sometimes overstimulates people, who may react to climate change with feelings such as apathy, fear, inaction, or denial (Roxburgh et al. Citation2019; El Barachi et al. Citation2021; Boon-Falleur et al. Citation2022). This aspect reveals the important role that emotions play with respect to people’s perceptions and beliefs, which shape the development of their ethical opinions regarding climate change and the frames that they use to understand that phenomenon (Spence and Pidgeon Citation2009; Pidgeon Citation2012). Therefore, we affirm the importance of the quality of the information and the purpose behind the communication of that specific information as a factor that can strongly influence people’s positions on climate change (Moser Citation2010; Boon-Falleur et al. Citation2022).

4.4. Limitations

All that being said, it is essential to acknowledge that behaviours observed on social media may not be easily generalized to offline society for several reasons. Firstly, there is a concern of sample bias since Twitter demographics are not fully representative of the overall population. This challenge persists because obtaining comprehensive demographic data from Twitter is almost impossible (Filho et al. Citation2015). Secondly, individuals who actively participate in political discussions often possess strong, and at times polarized, opinions about the topics under consideration (Yardi and Boyd Citation2010).

5. Conclusion: implications for policy design

The narratives that people frame in relation to climate change have direct implications for the design of future environmental and climate policies, given that a greater or lesser acceptance of such policies is closely related to these different narratives (Ryan et al. Citation2011). If we do not trust scientific evidence and if we do not take scientific models and information concerning climate change seriously, how can our individual and collective consciousness ever come to believe in climate policies and increase our willingness to address the issue of climate change? Therefore, climate policies should integrate into their designs the distinct narratives and imaginaries that emerge in the context of social media, considering such contexts to be spaces for subjective expression in addition to the scientific and universal expression required for science (Pearce et al. Citation2019).

Such policies could be aimed at increasing information and education as well as engagement and action, thereby leading to significant sociocultural changes (IPCC Citation2021). The use of flood maps in accordance with the distinct global warming scenarios referenced by Climate Central’s publication was able to provoke individual and subjective reactions by involving the users directly and inspiring them to post or reply to a tweet. Reflecting on this aspect, we consider the task of “putting a face on” or “visualising” the effects of climate change to be fundamental for climate policies, especially with respect to effects that are more gradual and difficult to observe, since such visualization can make these effects more tangible, personal, and real (Retchless Citation2018).

Climate policies must confront an important challenge regarding the need to reduce the ontological gap between the effects of climate change and human activities. The ultimate purpose would be to communicate to society that certain human pressures and habits can have, and are already having, impacts on the processes that shape the planet so that humans can implement effective solutions to solve these problems (IPCC Citation2021). Otherwise, they will prefer to build the ark calmly while waiting for the sea to arrive at their doorsteps.

Consent for publication

All authors give their consent for publication of this manuscript and all the information related, including authors’ information.

Authors contributions

JP designed the study, JP and EG collected and analysed the data, JP and EG wrote and reviewed the manuscript, JP and EG prepared the figures.

Acknowledgments

This publication is part of the R&D&i project “Adaptación a los riesgos asociados al cambio climático en espacios turísticos del litoral mediterráneo: percepción, incentivos y barreras” (reference PID2019-104480GB-I00) funded by MCIN (10.13039/501100011033). The authors would like also to thank David Alegre Lorenz for his assistance and effort for the tweets’ classification process.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

The data used in this study is available in a Zenodo repository at https://zenodo.org/record/6559169

Additional information

Funding

References

- Benjamin J, Rovere A, Fontana A, Furlani S, Vacchi M, Inglis RH, Galili E, Antonioli F, Sivan D, Miko S, et al. 2017. Late quaternary sea-level changes and early human societies in the central and eastern Mediterranean basin: an interdisciplinary review. Quatern Int. 449:29–19. doi: 10.1016/j.quaint.2017.06.025.

- Boon-Falleur M, Grandin A, Baumard N, Chevallier C. 2022. Leveraging social cognition to promote effective climate change mitigation. Nat Clim Chang. 12(4):332–338. doi: 10.1038/s41558-022-01312-w.

- Bovey WH, Hede A. 2001. Resistance to organisational change: the role of defence mechanisms. J Manag Psychol. 16(7):534–548. doi: 10.1108/EUM0000000006166.

- Boykoff M, Pearman O. 2019. Now or never: how media coverage of the IPCC special report on 1.5°C shaped Climate-Action Deadlines. One Earth. 1(3):285–288. doi: 10.1016/j.oneear.2019.10.026.

- Brewer PR, McKnight J. 2015. Climate as comedy. Sci Commun. 37(5):635–657. doi: 10.1177/1075547015597911.

- Burger J, Gochfeld M, Pittfield T, Jeitner C. 2016. Perceptions of climate change, sea level rise, and possible consequences relate mainly to self-valuation of science knowledge. Physiology & Behavior. 176(8):139–148. doi: 10.4236/epe.2016.85024.Perceptions.

- Casas-Prat M, Sierra JP. 2012. Trend analysis of wave direction and associated impacts on the Catalan coast. Clim Change. 115(3–4):667–691. doi: 10.1007/s10584-012-0466-9.

- Climate Central. (2021). Picturing Our Future - Climate Central. https://coastal.climatecentral.org/map/9/2.4294/41.9522/?theme=warming&map_type=multicentury_slr_comparison&basemap=roadmap&elevation_model=best_available&lockin_model=levermann_2013&refresh=true&temperature_unit=C&wa

- Cody EM, Reagan AJ, Mitchell L, Dodds PS, Danforth CM, Lehmann S. 2015. Climate change sentiment on Twitter: an unsolicited public opinion poll. PloS One. 10(8):1–18. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0136092.

- Covi MP, Kain DJ. 2016. Sea-level rise risk communication: public understanding, risk perception, and attitudes about information. Environ Commun. 10(5):612–633. doi: 10.1080/17524032.2015.1056541.

- Cramer W, Guiot J, Fader M, Garrabou J, Gattuso JP, Iglesias A, Lange MA, Lionello P, Llasat MC, Paz S, et al. 2018. Climate change and interconnected risks to sustainable development in the Mediterranean. Nat Clim Chang. 8(11):972–980. doi: 10.1038/s41558-018-0299-2.

- Curnock MI, Marshall NA, Thiault L, Heron SF, Hoey J, Williams G, Taylor B, Pert PL, Goldberg J. 2019. Shifts in tourists’ sentiments and climate risk perceptions following mass coral bleaching of the great barrier reef. Nat Clim Chang. 9(7):535–541. doi: 10.1038/s41558-019-0504-y.

- El Barachi M, AlKhatib M, Mathew S, Oroumchian F. 2021. A novel sentiment analysis framework for monitoring the evolving public opinion in real-time: case study on climate change. J Clean Prod. 312(May):127820. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.127820.

- Entman RM. 1993. Framing: toward clarification of a Fractured Paradigm. J Commun. 43(4):51–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x.

- Filho RM, Almeida JM, Pappa GL (2015). Twitter population sample bias and its impact on predictive outcomes: a case study on elections. Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Advances in Social Networks Analysis and Mining, ASONAM 2015, 1254–1261. 10.1145/2808797.2809328

- Fleiss JL. 1971. Measuring nominal scale agreement among many raters. Psychol Bull. 76(5):378–382. doi: 10.1037/h0031619.

- Gabarda-Mallorquí A, Fraguell RM, Ribas A. 2018. Exploring environmental awareness and behavior among guests at hotels that apply water-saving measures. Sustainability. 10(5):1305. doi: 10.3390/su10051305.

- Garcia-Lozano C, Pintó J, Daunis-I-Estadella P. 2018. Reprint of changes in coastal dune systems on the Catalan shoreline (Spain, NW Mediterranean sea). Comparing dune landscapes between 1890 and 1960 with their current status. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci. 211:23–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ecss.2018.07.024.

- Hamed AA, Ayer AA, Clark EM, Irons EA, Taylor GT, Zia A. 2015. Measuring climate change on Twitter using Google’s algorithm: perception and events. Int J Web Inf Syst. 11(4):527–544. doi: 10.1108/IJWIS-08-2015-0025.

- IPCC. (2021). Summary for policymakers. In climate change 2021: the physical science basis. Contribution of Working group I to the sixth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on climate change. Cambridge University Press.

- Jacques PJ, Knox CC. 2016. Hurricanes and hegemony: a qualitative analysis of micro-level climate change denial discourses. Env Polit. 25(5):831–852. doi: 10.1080/09644016.2016.1189233.

- Jang SM, Hart PS. 2015. Polarized frames on “climate change” and “global warming” across countries and states: evidence from Twitter big data. Glob Environ Chan. 32:11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2015.02.010.

- Jasny L, Waggle J, Fisher DR. 2015. An empirical examination of echo chambers in US climate policy networks. Nat Clim Chang. 5(8):782–786. doi: 10.1038/nclimate2666.

- Jenkins-Smith HC, Ripberger JT, Silva CL, Carlson DE, Gupta K, Carlson N, Ter-Mkrtchyan A, Dunlap RE. 2020. Partisan asymmetry in temporal stability of climate change beliefs. Nat Clim Chang. 10(4):322–328. doi: 10.1038/s41558-020-0719-y.

- Jiménez JA, Valdemoro HI, Bosom E, Sánchez-Arcilla A, Nicholls RJ. 2017. Impacts of sea-level rise-induced erosion on the Catalan coast. Reg Environ Chan. 17(2):593–603. doi: 10.1007/s10113-016-1052-x.

- Leviston Z, Walker I, Morwinski S. 2013. Your opinion on climate change might not be as common as you think. Nat Clim Chang. 3(4):334–337. doi: 10.1038/nclimate1743.

- Loizidou M, Giannakopoulos C, Bindi M, Moustakas K. 2016. Climate change impacts and adaptation options in the Mediterranean basin. Reg Environ Chan. 16(7):1859–1861. doi: 10.1007/s10113-016-1037-9.

- Lyytimäki J. 2021. Ecological crisis as a laughing matter. In: The handbook of international trends in environmental communication. Routledge; pp. 464–478. doi:10.4324/9780367275204-35.

- Moser SC. 2010. Communicating climate change: history, challenges, process and future directions. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Clim Change. 1(1):31–53. doi: 10.1002/wcc.11.

- O’Neill S, Boykoff M. 2010. Climate denier, skeptic, or contrarian? Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 107(39). doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010507107.

- O’Neill S, Williams HTP, Kurz T, Wiersma B, Boykoff M. 2015. Dominant frames in legacy and social media coverage of the IPCC fifth assessment report. Nat Clim Chang. 5(4):380–385. doi: 10.1038/nclimate2535.

- Pearce W, Niederer S, Özkula SM, Sánchez Querubín N. 2019. The social media life of climate change: platforms, publics, and future imaginaries. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Clim Change. 10(2):1–13. doi: 10.1002/wcc.569.

- Pickering CM, Norman P. 2020. Assessing discourses about controversial environmental management issues on social media: tweeting about wild horses in a national park. J Environ Manage. [November2019] 275:111244. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.111244.

- Pidgeon N. 2012. Climate change risk perception and communication: addressing a critical moment? Computat Studies. 32(6):951–956. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.2012.01856.x.

- Pilfold N, McCall A, Derocher A, Lunn N, Richardson E. 2017. Migratory response of polar bears to sea ice loss: to swim or not to swim. Ecography. 40(1):189–199. doi: 10.1111/ecog.02109.

- Pueyo-Ros J, Garcia X, Ribas A, Fraguell RM. 2018. Ecological restoration of a coastal wetland at a mass tourism Destination. Will the recreational value increase or decrease? Ecol Econ. 148(February):1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2018.02.002.

- Pueyo-Ros J, Ribas A, Fraguell RM. 2018. Uses and preferences of visitors to coastal wetlands in tourism destinations (Costa Brava, Spain). Wetlands. 38(6):1183–1197. doi: 10.1007/s13157-017-0954-9.

- Retchless DP. 2018. Understanding local sea level rise risk perceptions and the power of maps to change them: the effects of distance and doubt. Environ Behav. 50(5):483–511. doi: 10.1177/0013916517709043.

- Ross AS, Rivers DJ. 2019. Internet Memes, media frames, and the conflicting logics of climate change discourse. Environ Commun. 13(7):975–994. doi: 10.1080/17524032.2018.1560347.

- Roxburgh N, Guan D, Shin KJ, Rand W, Managi S, Lovelace R, Meng J. 2019. Characterising climate change discourse on social media during extreme weather events. Glob Environ Chan. 54:50–60. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2018.11.004.

- Ryan A, Gorddard R, Abel N, Leitch A, Alexander K, Wise R. 2011. Perceptions of Sea‐Level Rise Risk and the Assessment of Managed Retreat Policy: Results from an Exploratory Community Survey in Australia CSIRO (pp. 54). Climate Adaptation National Research Flagship.

- Shi J, Visschers VHM, Siegrist M, Arvai J. 2016. Knowledge as a driver of public perceptions about climate change reassessed. Nat Clim Chang. 6(8):759–762. doi: 10.1038/nclimate2997.

- Spence A, Pidgeon N. 2009. Psychology, climate change & sustainable behaviour. Environment. 51(6):8–18. doi: 10.1080/00139150903337217.

- Swim JK, Bloodhart B. 2015. Portraying the perils to polar bears: the role of empathic and objective perspective-taking toward animals in climate change communication. Environ Commun. 9(4):446–468. doi: 10.1080/17524032.2014.987304.

- Tamburrini N, Cinnirella M, Jansen VAA, Bryden J. 2015. Twitter users change word usage according to conversation-partner social identity. Soc Networks. 40:84–89. doi: 10.1016/j.socnet.2014.07.004.

- Taylor A, De Bruin WB, Dessai S. 2014. Climate change beliefs and perceptions of weather-related changes in the United Kingdom. Computat Studies. 34(11):1995–2004. doi: 10.1111/risa.12234.

- Torres-Bagur M, Ribas A, Vila-Subirós J. 2019. Perceptions of climate change and water availability in the Mediterranean tourist sector: a case study of the muga River basin (Girona, Spain). IJCCSM. 11(4):552–569. doi: 10.1108/IJCCSM-10-2018-0070.

- Vikström S, Mervaala E, Kangas H-L, Lyytimäki J. 2023. Framing climate futures: the media representations of climate and energy policies in Finnish broadcasting company news. J Integr Environ Sci. 20(1). doi: 10.1080/1943815X.2023.2178464.

- Weber EU. 2010. What shapes perceptions of climate change? Wiley Interdiscip Rev Clim Change. 1(3):332–342. doi: 10.1002/wcc.41.

- Weber EU. 2016. What shapes perceptions of climate change? New research since 2010. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Clim Change. 7(1):125–134. doi: 10.1002/wcc.377.

- Weber EU, Stern PC. 2011. Public understanding of climate change in the United States. Am Psychol. 66(4):315–328. doi: 10.1037/a0023253.

- Wei Y, Gong P, Zhang J, Wang L. 2021. Exploring public opinions on climate change policy in “Big Data Era”—A case study of the European Union Emission Trading System (EU-ETS) based on Twitter. Energ Policy. 158(January):112559. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2021.112559.

- Whitmarsh L. 2008. Are flood victims more concerned about climate change than other people? the role of direct experience in risk perception and behavioural response. J Risk Res. 11(3):351–374. doi: 10.1080/13669870701552235.

- Whitmarsh L. 2011. Scepticism and uncertainty about climate change: dimensions, determinants and change over time. Glob Environ Chan. 21(2):690–700. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.01.016.

- Williams HTP, McMurray JR, Kurz T, Hugo Lambert F. 2015. Network analysis reveals open forums and echo chambers in social media discussions of climate change. Glob Environ Chan. 32:126–138. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2015.03.006.

- Yardi S, Boyd D. 2010. Dynamic debates: an analysis of group polarization over time on Twitter. Bull Sci Technol Soc. 30(5):316–327. doi: 10.1177/0270467610380011.