ABSTRACT

Objective: Adolescents are at risk for substance use, sexual assault, and sexual risk behaviours; however, to date no integrated prevention programmes address all three risk behaviours. The goal of this study was to evaluate the usability and acceptability of Teen Well Check, an e-health prevention programme targeting substance use, sexual assault, and sexual risk among adolescents in primary care settings.

Methods: The current study included content analysis of interviews with adolescents in primary care (aged 14–18; n = 25) in the intervention development process, followed by usability and acceptability testing with qualitative interviews among adolescents in primary care (aged 14–18; n = 10) and pediatric primary care providers (n = 11) in the intervention refinement process. All data were collected in the Southeastern U.S.

Results: Feedback on Teen Well Check addressed content, engagement and interaction, language and tone, aesthetics, logistics, inclusivity, parent/guardian-related topics, and the application of personal stories. Overall, providers reported they would be likely to use this intervention (5.1 out of 7.0) and recommend it to adolescents (5.4 out of 7.0).

Conclusions: These findings suggest preliminary usability and acceptability of Teen Well Check. A randomized clinical trial is needed to assess efficacy.

Highlights

Adolescents are at risk for substance use, sexual assault, and sexual risk behaviours.

The goal of this study was to evaluate the usability and acceptability of Teen Well Check, an e-health prevention programme targeting substance use, sexual assault, and sexual risk among adolescents in primary care settings.

Providers and adolescents rated Teen Well Check as usable and acceptable, and providers indicated that they would recommend it to their adolescent patients.

Objetivo: Los adolescentes están en riesgo de uso de substancias, agresión sexual y conductas sexuales de riesgo; sin embargo, hasta la fecha, no existen programas de prevención integrados que aborden estas tres conductas de riesgo. El objetivo de este estudio fue evaluar la utilidad y aceptabilidad de Chequeo del Bienestar del Adolescente (Teen Well Check), un programa electrónico de salud centrado en el uso de substancia, agresión sexual y riesgo sexual entre adolescentes en contextos de atención primaria.

Métodos: El presente estudio incluyó análisis de contenido de entrevistas con adolescentes en atención primaria (edades de 14 a 18 años; n = 25) en el proceso de desarrollo de la intervención, seguido por la evaluación de la utilidad y aceptabilidad con entrevistas cualitativas con adolescentes en atención primaria (edades de 14 a 18 años; n = 10) y proveedores de atención primaria a nivel pediátrico (n = 11) en el proceso de refinamiento de la intervención. Todos los datos fueron recolectados en el sudeste de los Estados Unidos.

Resultados: La retroalimentación del Teen Well Check abordó contenido, participación e interacción, lenguaje y tono, estética, logística, inclusión, temas relacionados con los padres o cuidadores, y la aplicación de historias personales. En general, los proveedores reportaron que ellos probablemente usarían esta intervención (5.1 de 7.0) y la recomendarían a los adolescentes (5.4 de 7.0).

Conclusiones: Estos hallazgos sugieren la utilidad y aceptabilidad preliminar de Teen Well Check. Un ensayo clínico aleatorizado es necesario para evaluar la eficacia.

目的:青少年面临物质使用、性侵犯和危险性行为的风险; 然而,迄今为止,还没有针对所有三种风险行为的综合预防方案。 本研究旨在评估青少年健康检查的可用性和可接受性,它是一项针对初级医疗环境中青少年物质使用、性侵犯和性风险的电子健康预防计划。

方法:本研究包括在干预开发过程中对初级医疗青少年(14–18 岁;n = 25)进行访谈的内容分析,然后对初级医疗青少年(14–18岁;n = 25)(14–18 岁;n = 10) 以及儿科初级医疗提供者 (n = 11) 在干预细化过程中的定性访谈进行可用性和可接受性检验。 所有数据均在美国东南部收集。

结果:对青少年健康检查的反馈涉及内容、参与和互动、语言和语气、审美、后勤、包容性、父母/监护人相关主题以及个人故事的应用。 总体而言,提供者报告说他们可能会使用这种干预措施(7.0 分中得5.1 分)并推荐给青少年(7.0 分中得 5.4 分)。 提供者将干预描述为对他们的患者‘有帮助’(7.0 分中得 5.2 分)。

结论:这些发现表明了青少年健康检查的初步可用性和可接受性。 需要进行随机临床试验来评估疗效。

Substance use, sexual assault, and sexual risk behaviours among adolescents are common and interrelated (Johnston et al., Citation2021; Scott-Sheldon et al., Citation2016; Smith et al., Citation2018). Among adolescents surveyed in the United States during 2018, past year substance use was 38.3% for alcohol, 24.6% for cannabis, 30.7% for any vaping, and 9.2% for illicit drugs other than cannabis (Johnston et al., Citation2021). Substance use and sexual behaviour often co-occur, with 22.4% of sexually active adolescents aged 14–18 years using substances before their most recent sexual encounter (Johnston et al., Citation2016). Impairments in sexual decision-making due to substance use can lead to a range of consequences, including sexual risk behaviours and non-consensual sex. Adolescents are disproportionally affected by the consequences of sexual assault and sexual risk behaviours, being more likely to contract sexually transmitted infections (STIs; Kreisel et al., Citation2021) be sexually victimized (Black et al., Citation2011), and experience hardship due to unwanted pregnancy (Noll et al., Citation2019). Prevalence of these risk behaviours among youth has increased since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic (Dumas et al., Citation2020; Masonbrink et al., Citation2022). Prevention of these three interrelated major public health concerns would significantly reduce mental and medical health burden.

Perceptions of peer behaviour and attitudes, or perceived social norms, are associated with alcohol use, drug use, sexual assault, and sexual risk behaviours among adolescents and young adults (Hoxmeier et al., Citation2018; Kantawong et al., Citation2021; Pedersen et al., Citation2017). Communication skills including how to talk about sex and sexual consent, as well as communication with parents and providers about risk behaviours, are associated with decreased alcohol use, drug use, sexual assault, and sexual risk behaviours (Hops et al., Citation2011). Personalized normative feedback and communication skills practice may be an effective cross-cutting strategy to reduce and prevent risk for alcohol and drug use, sexual assault, and sexual risk behaviours among adolescents.

Many adolescents seek routine preventative healthcare in primary care settings. Recent health reforms have improved population health outcomes and primary care services (Hofer et al., Citation2011). e-Health screening and brief interventions allow standardized screening for adolescents prior to meeting with the primary care provider. Adolescents also prefer technology-based screening (Gibson et al., Citation2021) compared to screening conducted by a provider. A systematic review and meta-analysis of eHealth interventions with adolescents to prevent risk behaviours found beneficial effects across a range of behaviours (Champion et al., Citation2019). This manuscript describes the development and acceptability testing of an e-Health integrated prevention programme for adolescent substance use, sexual assault, and sexual risk behaviours in primary care settings using the Intervention Mapping framework (Bartholomew Eldredge et al., Citation2016). The aim of this project was to develop an intervention that could be disseminated into primary care settings without adding burden to primary care providers.

1. Methods

1.2. Participants and procedures

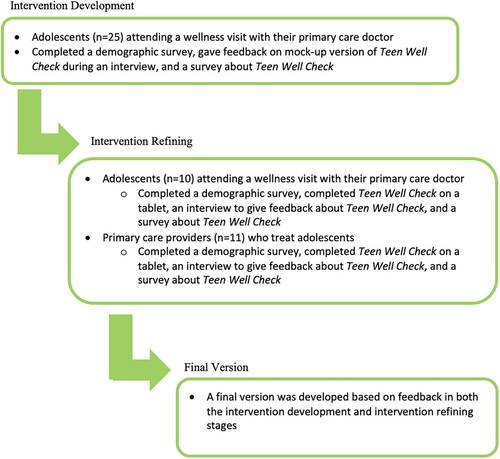

All study procedures (see ) were approved by the university IRB and were completed between April 2018 and October 2021. All data were collected in the Southeastern USA.

The intervention was developed using the Intervention Mapping framework (Bartholomew Eldredge et al., Citation2016) and followed practices consistent with the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) checklist (see ). For a description of the target outcomes and theoretical components, see . Theory-based processes and qualitative interviews with adolescents (Intervention Development Phase described below) were used to develop the intervention. Using the Intervention Mapping Framework, we translated methods and strategies into an organized programme, consulted with intended participants and stakeholders, prepared programme materials and piloted programme materials for feedback on the acceptability of the programme from providers and adolescent patients (Intervention Refinement Phase described below). In the intervention development process, we prioritized using theory-based methods and content that were acceptable to providers and adolescent patients that would not add burden to primary care providers and disrupt clinic flow. Stakeholders in this process were primary care providers and they gave in-depth feedback on Teen Well Check during the Intervention Refinement phase.

Table 1. Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) checklist.

1.2.1. Intervention development phase

Adolescents aged 14–18 years old (n = 25), attending a wellness visit at their primary care doctor were approached in the waiting room or patient room by research staff to complete an eligibility screen for the study. See for participant information. All procedures were conducted at academic medical centres that primarily served low-income families insured by Medicaid. The eligibility screen assessed if adolescents met the following eligibility criteria: between 14 and 18 years old, could read and understand English, did not have a developmental disability that would prevent them from understanding the programme contents, and reported knowing a peer who has ever used substances. Eligible individuals then consented (parents) and assented (adolescents) to the study procedures. Adolescents completed a questionnaire on a tablet, interview to provide feedback on the intervention development phase of Teen Well Check (see and below for more information) using screenshot mockups shown to adolescents on a tablet by research staff, and questionnaire about the intervention on a tablet. All study procedures after the consent process were conducted in a private room in the clinic without the parent present. Participants received a $20 gift card for participation.

Table 2. Theory- and evidence-based components in Teen Well Check.

1.2.2. Intervention refinement phase

Adolescents aged 14–18 years old (n = 10), completed the same procedure process as the Intervention Development phase but viewed the entire programmed Teen Well Check programme (see and below for more information) that was programmed in a tablet-based application. See for participant information. There was no overlap in adolescents in the samples.

Further, we completed usability and acceptability testing via interviews among pediatric primary care providers in community clinics (n = 11). Providers were shown screenshots of the programme during the interview and were compensated via a $100 gift card drawing.

1.3. Teen Well Check development using iterative, end-user focused design

Teen Well Check contains three modules created for this intervention specific to substance use, sexual risk behaviour, and sexual assault, presented in a linear fashion using a motivational interviewing approach. The content of the intervention was designed based on existing literature and published theory as described below and outlined in .

1.3.1. Substance use module

Participants received personalized feedback on perceived and actual age- and gender-specific substance use, psychoeducation regarding the effect of substance use on brain development, their own consequences experienced, and psychoeducation related to the substance of choice (1. Vaping/cigarettes/Juul; 2. Alcohol; 3. Cannabis/marijuana; 4. Prescription opioids; 5. Other drugs). If participants only used one substance, they learned about that substance. If they used multiple substances, they chose which substance they had used that they wanted to learn about. If participants had not used substances, they were provided an option to learn about any substance. Psychoeducation also included a short video developed by NIDA about brain anatomy, physiology, and effects of substance use (National Institute on Drug Abuse [NIDA/NIH], Citation2019).

1.3.2. Sexual risk module

Participants were asked questions and provided feedback about how many adolescents their age had been tested for STIs and how many used substances prior to engaging in sexual behaviour. Psychoeducation focused on condom use and how substances can impact sexual communication.

1.3.3. Sexual assault module

Scenarios of potential sexual assault situations were provided where participants could learn how to respond as a potential victim, perpetrator, or bystander. Information regarding sexual consent was also provided, including information about how substances can impact sexual consent.

1.3.4. Teen Well Check intervention development

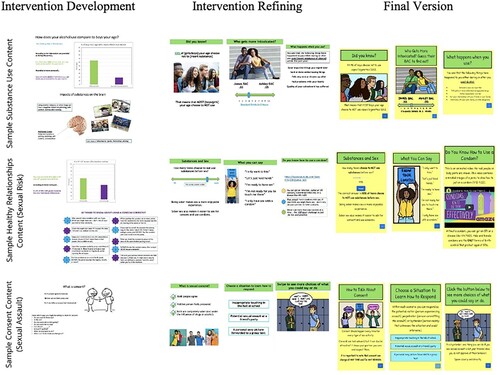

The intervention development phase (see ) included ten mock-up designs that were displayed to participants on a tablet. Mock-up designs were developed using theory-based cross-cutting targets identified by the research team. After receiving feedback on the intervention development phase mock-ups, interviews were analyzed. Once results were identified and thematic saturation was achieved, adaptations were made to the content by the research team.

1.3.5. Teen Well Check intervention refinement

Teen Well Check was optimized for use on a tablet to be delivered in primary care waiting rooms. It was presented to teens and providers, where interviews were determined to be completed after reaching thematic saturation. Adolescent feedback was used to make adaptations to the content by the research team during the final iteration, which was programmed into a web-based prevention programme (see ). In each stage, all adaptations requested were made unless there was disagreement among participants or if it was not feasible within the scope of the study.

1.3.6. Teen Well Check logistics

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, teen wellness visits usually lasted 30 min and intake paperwork (including substance use screening forms) was completed before arrival or in the waiting room before the appointment started. The initial concept of Teen Well Check was for it to be delivered in the waiting room in a single session of 5–15 min. Due to the clinic flow shift that occurred during the pandemic, patients waited in their cars or outside of the clinic rather than in waiting rooms as was typical pre-COVID. For this reason, combined with the concern about sanitizing requirements for tablets, Teen Well Check was programmed to be accessible remotely via a personal device.

1.4. Measures

Interview. Adolescents and providers completed a semi-structured interview ranging from 30 to 60 min to provide feedback about Teen Well Check, including aesthetics, content, and interest in using the intervention.

Acceptability and usability were assessed among adolescents and providers using the Post Study System Usability Questionnaire (PSSUQ) (Lewis, Citation2002) and questions developed by the research team. The PSSUQ is a 19-item instrument that measures satisfaction with a computer system (Bartholomew Eldredge et al., Citation2016) with answer choices ranging from ‘Strongly Agree’ (1) to ‘Strongly Disagree’ (7). Lower scores indicate more acceptability and usability. Providers were also asked the likelihood of using and recommending Teen Well Check ranging from ‘Very Unlikely’ (1) to ‘Very Likely’ (7). Mean scores will be used. ().

Table 3. Characteristics of primary care providers (n = 11) and adolescents 14–18 years (n = 35).

1.5. Qualitative data analysis

Interviews were content analyzed using an iterative team-based approach led by a PhD-level researcher. The researcher reviewed each transcript and developed a list of topics that emerged both deductively from the interview guide and inductively from participants’ responses. Using those topic lists as a preliminary codebook and NVivo (QSR International Pty Ltd, Citation2018), two research staff members separately coded (White et al., Citation2022) the transcripts, compared and refined codes for each transcript, and reconciled their coding until they had 100% agreement (i.e. reviewed coding together in real-time and came to agreement). Coders developed analytic memos for each code, noting major findings and important quotations. The researcher used those analytic memos, reports from NVivo (ex: code co-occurrence, transcript coverage), and the coded quotations to identify the most salient results.

2. Results

2.1. Intervention development phase of Teen Well Check: adolescent feedback

2.1.1. Aesthetics

Participants provided feedback on how to improve aesthetics of pictures, animations, and videos (see Quote 1 in ). Formatting feedback was provided to improve aesthetic acceptability of the intervention, including commenting on the colour scheme and font. Participants suggested adding more visual components and images to enhance usability throughout the programme. Participants commented on the importance of using images and language that were inclusive and representative of diverse identities (see for sample quotes).

Table 4. Sample feedback quotes on phase of Teen Well Check.

2.1.2. Alcohol & substance use

Participants also provided feedback on content-specific aspects of the intervention. Specific to substance use, participants liked the alcohol-related content and responded positively to brain-related substance use content (see Quote 2 in ). Participants also suggested expanding information about substance use. Participants requested more content on the relation between substance use and the brain, wanted definitions or content to be clarified, and wanted more information on the consequences of substance use (see ).

2.1.3. Sexual risk behaviours

Overall, participants had positive reactions to the sexual risk behaviour content. Participants suggested including content on the prevalence of STIs and the consequences of sexual risk behaviours without protection or with multiple partners. Participants reported that it would be useful to include a video on using sexual protection such as a condom properly (see Quote 3 in ).

2.1.4. Sexual assault

Participants desired additional strategies to prevent sexual assault. Participants also suggested adding more scenarios from the perspectives of the victim, perpetrator, and bystander. Participants provided feedback on sections related to consent and wanted consent definitions with examples of consensual and non-consensual sexual activity. Participants also expressed the need for language around how to ask for consent, sexual refusal, and the importance of ongoing consent (see Quote 4 in ).

2.2. Intervention refinement phase of Teen Well Check: adolescent and provider feedback

2.2.1. Engagement and interaction

Providers and adolescents indicated that Teen Well Check was engaging and interactive through its inclusion of videos, interactive questions and scenarios, and personalized tailoring to adolescents’ pre-survey answers and preferences (see Quote 5 in ). Providers and teens universally had positive comments about including the short video developed by NIDA about brain anatomy, physiology, and effects of substance use (National Institute on Drug Abuse [NIDA/NIH], Citation2019).

Providers and adolescents wanted more interactive components of Teen Well Check. Specifically, responses indicated that they would like to see more interactive bystander scenarios (e.g. more ‘clicking,’ more videos, and more ‘quizzes’ to test their knowledge; see Quote 6 in ).

2.2.2. Language and tone

Providers and adolescents emphasized the need for brevity, clarity, and not including too much information or text on the screen. Providers and adolescents both appreciated clear definitions and intentional diction. Generally, providers and adolescents agreed the app did and should continue to use a motivational interviewing approach rather than ‘scare tactics’ and should ‘meet people where they are’ rather than ‘being judgy’ or presenting ‘all or nothing’ scenarios (see Quotes 7 and 8 in ).

2.2.3. Inclusivity

Providers and adolescents encouraged more inclusivity throughout the Teen Well Check app, particularly for trans, non-binary, or those with gender non-conforming identities, as well as inclusion of racial and ethnic minorities. Participants suggested the inclusion of same-sex couples, images of non-binary people, and avoiding binary language such as ‘boy–girl’ or ‘he-she.’ Some providers and adolescents pointed out that the sexual assault scenarios all positioned boys as perpetrators and girls as victims and suggested having scenarios with boys as victims (see Quotes 9 and 10 in ).

2.2.4. Aesthetics and images

Providers and adolescents mostly disliked the stock photos used throughout Teen Well Check, preferring the comic book style images used within the sexual assault module. One participant noted, ‘The circle full of teenagers, it just— it's like a little cliché,’ as did another, stating, ‘Don't use people pictures.’ In fact, some providers predicted that adolescents would find the photos of teens to be ‘hokey’ while also suggesting adolescents would respond well to the comic style (see Quotes 11 and 12 in ). Providers liked Teen Well Check's bright colours, and most adolescents said they enjoy the ‘very bright’ colours ‘which really attracts people's attention’. They noted that they wanted the programme to be ‘aesthetically pleasing’ and ‘cute’.

2.2.5. Personal background and the use of stories

Several providers and adolescents mentioned the importance of using stories and anecdotes to help users understand and engage more deeply with the material (see Quotes 13 and 14 in ).

2.2.6. Logistics and information sharing

Providers expressed concerns about how the 15-minute Teen Well Check intervention would be delivered in the waiting room, including lack of sufficient time and privacy (e.g. from guardians and other patients), difficulty ‘keeping a teenager's focus’ in the context of the pandemic clinic flow. Several participants suggested the intervention should be made available online, allowing participants to complete in their own time from a convenient and private location (see Quote 15 in ). Providers also emphasized the importance of sharing resources with adolescents, connecting them to necessary referrals, and sharing information with the parents to offer appropriate care.

2.2.7. Provider impressions of parent/guardian-related topics

When researchers asked how guardians would respond to Teen Well Check, providers described a variety of expected responses, anticipating that some guardians would be supportive, with others being uncomfortable, particularly with ‘the sex part.’ Providers emphasized they ask their adolescent patients drug, alcohol, and sex questions, but it is done during the confidential history portion of the exam, as allowed by state laws. Adolescents similarly emphasized the importance of resources like Teen Well Check but expressed concerns about confidentiality and privacy (see ).

2.3. Acceptability and usability: adolescents and providers

Most providers were very interested in using a prevention programme like Teen Well Check in their practice, especially if the necessary technology is provided. This high level of interest was reflected in our survey data (see ). When asked how likely they would be to (1) use this intervention and (2) recommend it to 14–18-year-olds, average provider responses indicated that providers would be somewhat likely to use the intervention in their clinical practice and recommend that adolescents use it. Providers were somewhat concerned about using a tablet-based intervention in the waiting room given the new clinic flow due to the pandemic, and recommended an online format. Therefore, the final version of Teen Well Check was adapted to an online format to be used at the clinic or after teens’ appointments based on clinic flow.

Table 5. Usability and acceptability of the Teen Well Check tablet-based intervention among primary care providers (n = 11) of adolescents 14–18 years in the Intervention Refinement process (n = 10).

In the interviews, most providers indicated that Teen Well Check was appropriate for 14–18-year-olds. Other providers felt the topics needed to be addressed at a younger age (e.g. 12 years old). Providers and adolescents ‘strongly agreed’ or ‘agreed’ that Teen Well Check was highly usable as assessed by the PSSUQ (Mprovider = 1.84; Madolescents = 1.24; see ).

3. Discussion

The current study assessed the usability and acceptability of Teen Well Check, an e-Health prevention programme targeting substance use, sexual assault, and sexual risk among teens in primary care settings, which provides an ideal window of opportunity for identification and prevention education for adolescents. Though the scientific premise for integrating prevention draws from previous work which outlines the interrelated nature of these health risk behaviours (George & Stoner, Citation2000; Hendershot & George, Citation2007; Testa & Livingston, Citation2009), no preventive work has been conducted to date targeting and integrating these three co-occurring risk behaviours among adolescents. Overall, teens and providers found the programme to be acceptable and useable, and providers indicated that they would be somewhat likely to use it in their clinical practice and recommend to adolescents. Teens and providers gave suggestions throughout the intervention's development, which were integrated into the final version of the programme.

When assessing feasibility of implementing Teen Well Check within a primary care setting, providers indicated that changes in clinic flow due to the direct result of the COVID-19 pandemic, a tablet-based programme delivered and completed in clinic waiting rooms may not be feasible. Therefore, the final version was accessible remotely via a personal device to maximize the connectivity of the prevention programme to the healthcare setting, given that is where adolescents learn about the programme, without taking away from routine healthcare. This approach could eventually allow for a very scalable implementation strategy if the programme is found to be efficacious because it can be made broadly accessible nationwide rather than based in specific clinics.

Adolescent participants indicated that improvements in usability and engagement may be achieved through gamifying Teen Well Check. Although this approach to intervention programming would be innovative and potentially useful, it was not feasible to use gamification due to development budget limitations during this study. Future research should consider including gamification in prevention programmes, as well as videos, comics, or quotes to integrate personal stories to enhance prevention, a strategy participant in the present study also suggested.

3.1. Limitations

To protect anonymity, the current interface does not integrate with medical records; however, to implement with pediatric primary care clinics nationwide, it may be useful for clinic buy-in to create a provider dashboard and to integrate with an electronic medical record. This would require significant funds due to the complexity of software needed to integrate with electronic medical record systems. Further, participant interactions with the programme were not recorded due to programming limitations in initial versions, which was addressed in the final version of the programme. A feasibility trial is needed to understand other field notes within one or more primary care settings to learn more about use, process, and how the providers would interface with the programme. If Teen Well Check is found to be feasible and efficacious, there is potential to expand this intervention to be tailored for specific groups of adolescents including tailoring based on race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, and age. Given that this is a prevention programme, it may be possible to tailor to a younger age as well.

4. Conclusions

The current study presents findings about the development and acceptability of Teen Well Check. Future research is required to understand if Teen Well Check effectively prevents substance use, sexual assault, and sexual risk among teens. Overall, Teen Well Check was acceptable to teens and providers, and prevention programmes targeting substance use, sexual assault, and sexual risk may be useful within primary care settings. More work is needed to assess the implementation feasibility and implementation barriers of Teen Well Check. Roll outs of clinical interventions in primary care settings can be a feasible way to address public health concerns.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge and thank all participants in this research study as well as Dr. Hollie Granato for the initial development of the sexual assault scenarios and Bea Stephens for the comic design.

Disclosure statement

Dr. Levy serves as an expert consultant for the case against JUUL. All other authors have no potential conflicts of interest to report.

Data availability statement

Due to the nature of this research, participants of this study did not agree for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data is not available.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bartholomew Eldredge, L. K., Markham, C. M., Ruiter, R. A. C., Fernández, M. E., Kok, G., & Parcel, G. S. (2016). Planning health promotion programs: An intervention mapping approach. Jossey-Bass.

- Black, M. C., Basile, K. C., Breiding, M. J., Smith, S. G., Walters, M. L., Merrick, M. T., Chen, J., & Stevens, M. R. (2011). The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010 summary report. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available from https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/nisvs_report2010-a.pdf

- Borsari, B., & Carey, K. B. (2001). Peer influences on college drinking: A review of the research. Journal of Substance Abuse, 13(4), 391–424. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0899-3289(01)00098-0

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press.

- Champion, K. E., Paramenter, B., McGowan, C., Spring, B., Wafford, Q. E., Gardner, L. A., Thornton, L., McBride, N., Barrett, E. L., Teesson, M., Newton, N. C., Chapman, C., Slade, T., Sunderland, M., Bauer, J., Allsop, S., Hides, L., Stapinksi, L., Birrell, L., & Mewton, L. (2019). Effectiveness of school-based eHealth interventions to prevent multiple lifestyle risk behaviours among adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Digital Health, 1(5), e206–e221. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2589-7500(19)30088-3

- Collins, R. L., Parks, G. A., & Marlatt, G. A. (1985). Social determinants of alcohol consumption: The effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 53(2), 189–200. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-006x.53.2.189

- Dimeff, L. A., Baer, J. S., Kivlahan, D. R., & Marlatt, G. A. (1999). Brief alcohol screening and intervention for college students: A harm reduction approach. Guilford Press.

- Dumas, T. M., Ellis, W., & Litt, D. M. (2020). What does adolescent substance use look like during the COVID-19 pandemic? Examining changes in frequency, social contexts, and pandemic-related predictors. Journal of Adolescent Health, 67(3), 354–361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.06.018

- Fischer, P., Krueger, J. I., Greitemeyer, T., Vogrincic, C., Kastenmüller, A., Frey, D., Heene, M., Wicher, M., & Kainbacher, M. (2011). The bystander-effect: A meta-analytic review on bystander intervention in dangerous and non-dangerous emergencies. Psychological Bulletin, 137(4), 517–537. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023304

- George, W. H., & Stoner, S. A. (2000). Understanding acute alcohol effects on sexual behavior. Annual Review of Sex Research, 11, 92–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/10532528.2000.10559785

- Gibson, E. B., Knight, J. R., Levinson, J. A., Sherritt, L., & Harris, S. K. (2021). Pediatric primary care provider perspectives on a computer-facilitated screening and brief intervention system for adolescent substance use. Journal of Adolescent Health, 69(1), 157–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.09.037

- Gidycz, C. A., McNamara, J. R., & Edwards, K. M. (2006). Women’s risk perception and sexual victimization: A review of the literature. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 11(5), 441–456. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2006.01.004

- Gilmore, A. K., Leone, R. M., Oesterle, D., Davis, K. C., Orchowski, L. M., Ramakrishnan, V., & Kaysen, D. (2022). Web-based alcohol and sexual assault prevention program with tailored content based on gender and sexual orientation: Preliminary outcomes and usability of Positive Change (+change). JMIR Formative Research, 6(7), e23823. https://doi.org/10.2196/23823

- Hendershot, C. S., & George, W. H. (2007). Alcohol and sexuality research in the AIDS era: Trends in publication activity, target populations and research design. AIDS and Behavior, 11(2), 217–226. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-006-9130-6

- Hendershot, C. S., Magnan, R. E., & Bryan, A. D. (2010). Associations of marijuana use and sex-related marijuana expectancies with HIV/STD risk behavior in high-risk adolescents. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 24(3), 404–414. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019844

- Hofer, A. N., Abraham, J. M., & Moscovice, I. (2011). Expansion of coverage under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act and primary care utilization. Milbank Quarterly, 89(1), 69–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0009.2011.00620.x

- Hops, H., Ozechowski, T. J., Waldron, H. B., Davis, B., Turner, C. W., Brody, J. L., & Barrera, M. (2011). Adolescent health-risk sexual behaviors: Effects of a drug abuse intervention. AIDS and Behavior, 15(8), 1664–1676. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-011-0019-7

- Hoxmeier, J. C., Flay, B. R., & Acock, A. C. (2018). Control, norms, and attitudes: Differences between students who Do and do not intervene as bystanders to sexual assault. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 33(15), 2379–2401. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260515625503

- Johnston, L. D., Miech, R. A., O’Malley, P. M., Bachman, J. G., Schulenberg, J. E., & Patrick, M. E. (2021). Monitoring the future national survey results on drug use 1975–2020: Overview, key findings on adolescent drug use. University of Michigan, Institute for Social Research. Available from: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED611736.pdf

- Johnston, L. D., O’Malley, P. M., Miech, R. A., Bachman, J. G., & Schulenberg, J. E. (2016). Monitoring the future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2015: Overview, key findings on adolescent drug use. University of Michigan, Institute for Social Research. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED578539.pdf

- Jouriles, E. N., Krauss, A., Vu, N. L., Banyard, V. L., & McDonald, R. (2018). Bystander programs addressing sexual violence on college campuses: A systematic review and meta-analysis of program outcomes and delivery methods. Journal of American College Health, 66(6), 457–466. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2018.1431906

- Kantawong, E., Kao, T. A., Robbins, L. B., Ling, J., & Anderson-Carpenter, K. D. (2021). Adolescents’ perceived drinking norms toward alcohol misuse: An integrative review. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 44(5), 477–492. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193945921998376

- Kreisel, K. M., Spicknall, I. H., Gargano, J. W., Lewis, F. M. T., Lewis, R. M., Markowitz, L. E., Roberts, H., Johnson, A. S., Song, R., St. Cyr, S. B., Weston, E. J., Torrone, E. A., & Weinstock, H. S. (2021). Sexually transmitted infections among US women and men: Prevalence and incidence estimates, 2018. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 48(4), 208–214. https://doi.org/10.1097/OLQ.0000000000001355

- Labhardt, D., Holdsworth, E., Brown, S., & Howat, D. (2017). You see but you do not observe: A review of bystander intervention and sexual assault on university campuses. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 35, 13–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2017.05.005

- Latané, B., & Darley, J. (1970). The unresponsive bystander: Why doesn’t he help? Appleton-Century Crofts.

- Latané, B., & Nida, S. (1981). Ten years of research on group size and helping. Psychological Bulletin, 89(2), 308–324. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.89.2.308

- Latané, B., & Rodin, J. (1969). A lady in distress: Inhibiting effects of friends and strangers on bystander intervention. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 5(2), 189–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1031(69)90046-8

- Lewis, J. R. (2002). Psychometric evaluation of the PSSUQ using data from five years of usability studies. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 14(3-4), 463–488. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2002.9669130

- Lewis, M. A., Litt, D., Cronce, J., Blayney, J. A., & Gilmore, A. K. (2014). Underestimating protection and overestimating risk: Examining descriptive normative perceptions and their association with drinking and sexual behaviors. The Journal of Sex Research, 51(1), 86–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2012.710664

- Lewis, M. A., & Neighbors, C. (2004). Gender-specific misperceptions of college student drinking norms. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 18(4), 334–339. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-164X.18.4.334

- Masonbrink, A. R., Middlebrooks, L., Gooding, H. C., Abella, M., Hall, M., Burger, R. K., & Goyal, M. K. (2022). Substance use disorder visits among adolescents at children’s hospitals during COVID-19. Journal of Adolescent Health, 70(4), 673–676. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.12.024

- Naar-King, S., & Suarez, M. (2011). Motivational interviewing with adolescents and young adults. Guilford Press.

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. (2011). Alcohol screening and brief intervention: A practitioner’s guide. http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/Practitioner/YouthGuide/YouthGuide.pdf

- National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA/NIH). (2019). Teen Brain Development [video on the Internet]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EpfnDijz2d8

- Noll, J. G., Guastaferro, K., Beal, S. J., Schreier, H. M. C., Barnes, J., Reader, J. M., & Font, S. A. (2019). Is sexual abuse a unique predictor of sexual risk behaviors, pregnancy, and motherhood in adolescence? Journal of Research on Adolescence, 29(4), 967–983. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12436

- Nurius, P. S., & Norris, J. (1996). A cognitive ecological model of women’s response to male sexual coercion in dating. Journal of Psychology & Human Sexuality, 8(1-2), 117–139. https://doi.org/10.1300/J056v08n01_09

- Pedersen, E. R., Osilla, K. C., Miles, J. N., Tucker, J. S., Ewing, B. A., Shih, R. A., & D’Amico, E. J. (2017). The role of perceived injunctive alcohol norms in adolescent drinking behavior. Addictive Behaviors, 67, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.11.022

- Perkins, H. W. (2002). Social norms and the prevention of alcohol misuse in collegiate contexts. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, Supplement, 14(s14), 164–172. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.164

- QSR International Pty Ltd. (2018). NVivo (Version 12). https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home

- Scott-Sheldon, L. A., Carey, K. B., Cunningham, K., Johnson, B. T., Carey, M. P., & The MASH Research Team. (2016). Alcohol use predicts sexual decision-making: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the experimental literature. AIDS and Behavior, 20(Suppl 1(0-1)), 19–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-015-1108-9

- Skinner, B. F. (1958). Reinforcement today. American Psychologist, 13(3), 94–99. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0049039

- Smith, S. G., Zhang, X., Basile, K. C., Merrick, M.T., Wang, J., Kresnow, M., & Chen, J. (2018). The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2015 Data brief – Updated release. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/2015data-brief508.pdf

- Steele, C. S., & Josephs, R. A. (1990). Alcohol myopia: Its prized and dangerous effects. American Psychologist, 45(8), 921–933. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.45.8.921

- Testa, M., & Livingston, J. A. (2009). Alcohol consumption and women’s vulnerability to sexual victimization: Can reducing women’s drinking prevent rape? Substance Use & Misuse, 44(9-10), 1349–1376. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826080902961468

- Ullman, S. E. (2014). Reflections on researching rape resistance. Violence Against Women, 20(3), 343–350. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801214526308

- White, K., Narasimhan, S. A., Hartwig, S., Carroll, E., McBrayer, A., Hubbard, S., Rebouché, R., Kottke, M., & Hall, K. S. (2022). Parental involvement policies for minors seeking abortion in the southeast and quality of care. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 19(1), 264–272. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-021-00539-0