ABSTRACT

Background: Post-traumatic stress symptoms (PTSS) following childbirth are common within a stressful environment and are mitigated by social support. During the COVID-19 pandemic, an increase in such symptoms has been reported. The current study aims to longitudinally model the influence of general and pandemic-specific risk and protective factors on the temporal unfolding of symptoms among postpartum women.

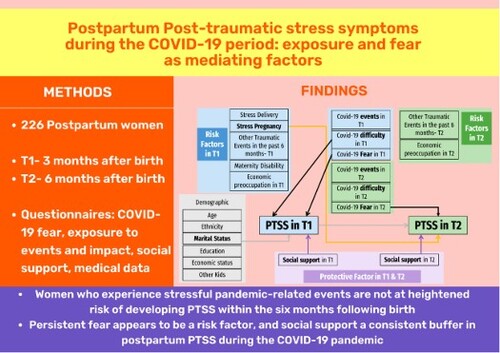

Methods: Participants were 226 women following a liveborn, term birth during the first lockdown in Israel. Participants completed questionnaires 10 weeks (T1) and 6 months (T2) after delivery. PATH analyses included predictors of symptoms in T1: demographics, exposure to traumatic events, medical complications during delivery or pregnancy, exposure to COVID-19-related events and their subjective impact, fear of COVID-19, and social support. Predictors of symptoms in T2 were: T1 predictors, both as direct effects and mediated by T1 PTSS, as well as predictors measured again in T2.

Results: Results showed the suggested model fit the data. The effect of COVID-19-related fear and subjective impact at T1 on symptoms at T2 were fully mediated by PTSS in T1, as were the effects of marriage and high social support at T1. COVID-19-related fear at T2 positively predicted symptoms at T2, while social support at T2 had the opposite effect. Medical complications during pregnancy negatively predicted symptoms in T2 only.

Discussion: Persistent fear appears to be a risk factor and supports a consistent buffer in postpartum PTSS during the COVID-19 pandemic. Medical complications during pregnancy served as a protective factor, possibly due to habituation to medical settings.

HIGHLIGHTS

Post-traumatic stress symptoms (PTSS) following childbirth during the COVID-19 pandemic may unfold in a unique manner, relating to pandemic-related stressors and fears.

Women who experience stressful pandemic-related events are not at heightened risk of developing PTSS within the six months following birth, but those reporting COVID-19 related fears are.

Women who had medical complications during pregnancy, but not delivery, are at lower risk of developing subsequent PTSS, perhaps due to their ongoing contact with medical facilities despite the pandemic.

Antecedentes: Los síntomas de estrés postraumático (SEPT) luego de dar a luz son comunes dentro de un ambiente estresante y son mitigados por el apoyo social. Durante la pandemia del COVID-19, se ha reportado un aumento en tales síntomas. El presente estudio busca modelar longitudinalmente la influencia de los factores protectores y de riesgo generales y específicos de la pandemia en el desarrollo temporal de los síntomas entre las mujeres después del parto.

Método: Las participantes fueron 226 mujeres después de un parto de término nacido vivo durante el primer confinamiento en Israel. Las participantes completaron cuestionarios a las 10 semanas (T1) y 6 meses (T2) luego de dar a luz. Los análisis PATH incluyeron predictores de síntomas en T1: las variables demográficas, la exposición a eventos traumáticos, las complicaciones médicas durante el parto o embarazo, la exposición a eventos relacionados al COVID-19 y su impacto subjetivo, el temor de COVID-19 y el apoyo social. Los predictores de los síntomas en T2 fueron: predictores de T1, tanto los efectos directos y mediados por los SEPT en T1, como también los predictores evaluados de nuevo en T2.

Resultados: Los resultados mostraron que el modelo sugerido se ajustó a los datos. El efecto del temor asociado al COVID-19 y el impacto subjetivo en T1 en los síntomas en T2 fueron completamente mediados por los SEPT en T1, como también los efectos del matrimonio y alto apoyo social en T1. El temor asociado con el COVID-19 en T2 predijo positivamente los síntomas en T2, mientras que el apoyo social en T2 tuvo el efecto opuesto. Las complicaciones médicas durante el embarazo predijeron negativamente los síntomas solo en T2.

Discusión: El temor persistente parece ser un factor de riesgo y amortigua consistentemente los SEPT después del parto durante la pandemia del COVID-19. Las complicaciones médicas durante el embarazo sirvieron como factores protectores, probablemente debido a la habituación a los contextos médicos.

背景:分娩后的创伤后应激症状 (PTSS) 在应激环境中很常见,可以通过社会支持得到缓解。在 COVID-19 疫情期间,报告的此类症状有所增加。本研究旨在对一般和疫情特定风险和保护因素对产后妇女症状随时间演变的影响进行纵向建模。

方法:参与者是 226 名在以色列第一次封锁期间活产、足月分娩的妇女。参与者在分娩后 10 周 (T1) 和 6个月 (T2) 完成问卷调查。路径分析纳入了 T1 症状的预测因素:人口统计学、创伤事件暴露、分娩或怀孕期间的医疗并发症、暴露于 COVID-19 相关事件及其主观影响、对 COVID-19 的恐惧和社会支持。T2 症状的预测因素是:T1 预测因素,既作为直接效应,也由 T1 PTSS 中介,以及在 T2 中再次测量的预测因素。

结果:结果显示提出的模型拟合了数据。 T1 时与 COVID-19 相关的恐惧和主观影响对 T2 症状的影响完全由T1 PTSS 中介,T1 中婚姻和高社会支持的影响也是如此。 T2 时与 COVID-19 相关的恐惧可以正向预测 T2 时的症状,而 T2 时的社会支持则产生相反的效果。怀孕期间的医疗并发症仅对 T2 中的症状产生负向影响。

讨论:持续的恐惧似乎是一个风险因素,并支持在 COVID-19 疫情期间持续缓冲产后 PTSS。怀孕期间的医疗并发症是一个保护因素,可能是由于对医疗环境的习惯。

1. Introduction

The Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has brought about a rise in numerous mental health adversities, such as higher rates of anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress (Xiong et al., Citation2020; Mental Health Impact of the COVID-Citation19 Pandemic: An Update, Citation2021). mental health has been shown to be influenced by many factors during the pandemic, some of them relating to the ways of communication with the general population (Su et al., Citation2021).

These mental health outcomes affect females at a greater prevalence than males (Ausín et al., Citation2021; Basu et al., Citation2021; Necho et al., Citation2021), and therefore, many studies have focused on the mental health of women during the pandemic, offering new insights about mental health issues and possible solutions (Su et al., Citation2022) while pregnant and post-partum females are especially vulnerable, presenting with concerns related to methods of protection, fear of infection and infant safety (Olde et al., Citation2006; Seng et al., Citation2009).

Due to the pandemic, governments worldwide have implemented lockdown periods, which have been shown to be negatively associated with the mental health of some populations (Visser & Law-van Wyk, Citation2021) and positively in others (Aqeel et al., Citation2022) With the emergence of the pandemic, healthcare systems have faced tremendous pressure worldwide. Even in routine times, postpartum mothers may experience Post Traumatic Stress Symptoms (PTSS) following childbirth, regardless of reaching the diagnostic criteria for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) (Basu et al., Citation2021; Necho et al., Citation2021). Some of the known factors which correlate with PTSS following childbirth include a history of psychological problems, obstetric procedures, low socioeconomic status (risk factors), and social support (protective factors) (Olde et al., Citation2006; Seng et al., Citation2009; Grekin & O’Hara, Citation2014; Liu et al., Citation2021; van Heumen et al., Citation2018). As a result of COVID-19, changes in childbirth conditions have been implemented in hospitals worldwide, as recommended by governments and public health organizations. In Israel, as of March 2020, these changes included regulations limiting one companion per parturient and limitation of medical staff per COVID-19-suspected parturient (Israeli Ministry of Health, Citation2020; Gluska et al., Citation2021).

Recent studies have described that, indeed, the prevalence of PTSS amongst postpartum mothers has risen during the COVID-19 pandemic (Berthelot et al., Citation2020; Ostacoli et al., Citation2020). Women who gave birth during COVID-19 and reported having no visitors during their hospital stay, were found to be at a greater risk for acute stress responses (Mayopoulos et al., Citation2020). This acute stress, in turn, has been found to be associated with PTSS following childbirth (Tzur Bitan et al., Citation2020). Considering the changes in the conditions of delivery and postpartum period due to the COVID-19 pandemic, it may be that reductions in perceived support, as well as stressors and fears directly related to COVID-19 that expecting mothers may have experienced, may incur a risk of PTSS following childbirth.

To the best of our knowledge, there are no published studies regarding the longitudinal change of PTSS throughout the COVID-19 pandemic amongst postpartum women. This longitudinal study aimed to evaluate the temporal development of maternal PTSS, and its relation to maternal exposure and fear of COVID-19, as well as to identify risk and protective factors for PTSS as they develop throughout the development of the pandemic.

In this study, it was hypothesized that exposure to COVID-19-related events, their subjective impact, and fear of COVID-19 would act as risk factors and therefore have a positive association with PTSS, as will previous physical and psychological disability, medical complications during pregnancy and birth, previous traumatic stressors, and socioeconomic status and current concerns. We also hypothesized that social support would be a protective factor and therefore have a negative association with PTSS.

2. Methods

This was a longitudinal, multicenter study that was conducted at three university-affiliated medical centres in Israel: Hillel Yaffe Medical Center (HYMC), Meir Medical Center (MMC), and Wolfson Medical Center (WMC), between 10 March and 9 May 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic strict lockdown period. The first part of the study, also called ‘Time 1’ (T1) was conducted approximately 10 weeks after childbirth, and the second part, ‘Time 2’ (T2) was conducted 6 months after childbirth following the second lockdown period – between 12 October and 8 December 2020. During T1, lockdown regulations included considerable restrictions on freedom of movement, shutdown of all non-essential services including medical services, and COVID-19 regulations during childbirth included limiting one companion per mother, extensive protective equipment for all medical staff assisting the delivery, limitation of medical staff per COVID-19-suspected mother, facial mask-wearing by mothers during all physical contact with the infant, and consideration of an enforced zero-separation policy for infants and mothers, meaning that mothers and infants are advised to stay together at all times (Health IM). From the beginning of May 2020 and after T1, the pandemic decreased, the lockdown was released, and schools reopened. For many people, life was ‘back to normal’. However, gradually the pandemic escalated until the second lockdown was initiated on 18 September 2020, for a period of three weeks. This lockdown was less strict, allowing considerable freedom of movement and with many services remaining open. The Institutional Review Board of each centre approved the study (HYMC-20-0079, MMC-0169-20, WMC-143-20).

2.1. Participants and procedure

Participants were recruited virtually, by a team of Hebrew and Arabic speaking physicians and medical students. Mothers who were under the age of 18 or who delivered earlier than 34 gestational weeks were excluded from the study. Informed consent was obtained both telephonically and electronically before data were collected from the participants. After consent, a text message was sent to each participant, containing a link to an online questionnaire in Hebrew or Arabic, according to the participant's preference. For the Arabic version, previously translated and validated questionnaires were used, or alternatively, questionnaires were translated and back translated by native Arabic speakers. Questionnaires were sent using the online “Qualtrics” survey platform. Only participants who completed at least 70% of the T1 questionnaire were included in the second section of the study (T2) which was conducted approximately 6 months after childbirth. Women were re-approached, asked for their further participation in the study, following the same protocol as in T1 and were given a similar online questionnaire. Upon inspection of the data, 257 women had completed the questionnaires utilized in this study at time 1, and of these, 226 women completed the utilized questionnaires at T2.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Demographics and obstetric data

The demographic questionnaire included items such as age, ethnicity, marital status, socioeconomic status, and level of education, as well as questions regarding COVID-19-related changes in economic concerns. Moreover, obstetric and pregnancy history, course of pregnancy, and course of delivery data were all retrieved from the computerized perinatal databases of each medical centre. Obstetric characteristics included parity, previous obstetric history, and current pregnancy follow-up (1st and 2nd-trimester genetic screening, anatomy scan, glucose status, and any hypertensive disorders). Parameters regarding the course of labour were also included – gestational age at delivery, need for induction of labour, anaesthesia, mode of delivery, and any birth complications and birth outcomes. In addition, variables concerning the postpartum course of both the mother and the newborn were collected including the number of hospitalization days and admission to a maternal or neonatal intensive care unit. These were coded into two binary variables delineating complications during pregnancy or delivery or lack thereof (for a full explanation, see Supplementary materials). Furthermore, a binary variable was coded delineating self-reported maternal disability, namely a physical, cognitive, or mental disability.

2.2.2. COVID-19 exposure and impact

This 14-item questionnaire was compiled to detect exposures to COVID-19-related life events, for example, ‘I was in contact with someone who was infected by the Coronavirus’. Each participant was asked to indicate whether or not she experienced such an event. Furthermore, in order to measure the subjective difficulty of these events, each participant was asked to indicate to which extent this exposure was difficult for her, on a three-point scale ranging from 1 (not difficult at all) to 3 (extremely difficult). Ultimately, the number of events was summed up (score 0–14), as well as the impact score of all events (score 0–42). As different women experienced different stressors and therefore responded to different items, internal consistency measures were unsurprisingly modest (Cronbach's alphas of 0.566 for exposures; 0.614 for subjective difficulty).

2.2.3. Fear of COVID-19 Scale (FVC-19S) (Ahorsu et al., Citation2022)

The FCV-19 is a self-report validated scale for the assessment of fear of COVID-19. To note, this questionnaire was also validated for the Hebrew language and the validated version is the one we used in the current study (Tzur Bitan et al., Citation2020). The scale is comprised of seven items regarding the fear response to COVID-19, for example: ‘I am afraid of losing my life because of the coronavirus’. Participants are requested to rate on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), with a total score of 7-35, a higher total score indicating greater fear of COVID-19. The questionnaire has a good internal validity (alpha Cronbach 0.82) and in the current study, the scale showed an internal consistency of 0.84.

2.2.4. Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPS) (Zimet et al., Citation2010)

The 12-item MSPS is a self-report scale for the assessment of subjective social support. The three subscales include support by family, friends, and significant others, and each subscale is represented by four items, for example: ‘There is a special person who is around when I am in need’. Participants are requested to respond using a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (very strongly disagree) to 7 (very strongly agree), a higher total score indicating greater subjective social support. The questionnaire has a good internal validity (alpha Cronbach 0.88) and in the current study the scale showed an internal consistency of 0.92.

2.2.5. Birth-related PTSS (City Birth Trauma Scale) (Ayers et al., Citation2018)

The 29-item self-report questionnaire includes 22 items referring to symptomology, based on the DSM-5 criteria. We used the validated Hebrew version (Handelzalts et al., Citation2018). The sum of the 22 symptom items was used to gauge birth-related PTSS severity. The questionnaire demonstrated good internal validity, with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.91.

2.3. Analytic strategy

Data were analysed using R software (version 4.0.3, R Project for Statistical Computing). Path analysis was utilized to assess the relationship between the variables (a path analysis model, visible in ). As predictors of post-traumatic stress symptoms in T1 we included demographic factors (age, ethnicity, marital status, education, salary at home, other kids in the family, maternal disability), traumatic stress (stressed delivery, traumatic pregnancy, traumatic events six months before the study), and COVID-19 risk factors (COVID-19 related traumatic events, COVID-19 impact, fear of COVID-19, economy stress due to COVID-19), and social support protective factor (MSPS) on the post-traumatic stress symptoms of the 226 valid women participants. As predictors of post-traumatic stress symptoms in T2, we included T1 predictors, either as direct effects or mediated by T1 PTSS, additional traumatic stressors for T2 (traumatic events six months before T2), COVID-19 risk factors in T2 (COVID-19 related traumatic events, COVID-19 impact, fear from COVID-19, economy stress due to COVID-19), and social support as a protective factor (MSPS) in time 2.

Figure 1. Path analysis results. Notes: Arrows display significant paths (*p ≤ .05, **p ≤ .01, ***p ≤ .001, ****p ≤ .0001) with standardized path coefficients in text. MSPS = Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support; PTSS = Posttraumatic stress symptoms; T1 = Time 1; T2 = Time 2.

Fit indices were used in order to evaluate model fit: chi-square statistic, degrees of freedom and p-value; root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) and its associated confidence interval (in well-fitting models should be between 0.05 to 0.07 with confidence interval lover then 0.08); the standardized root mean residual (SRMR, under 0.10 considered good-fitting model); the comparative fit index (CFI = >0.95 is indicative as good fit). One parsimony fit index (e.g. PNFI) was suggested as well, although we chose to omit it due to a lack of determinate threshold (Hooper et al., Citation2008).

We additionally conducted Chi-square tests (for categorical variables) and paired t-tests (for continuous variables) to compare (a) responses during T1 and during T2, and (b) differences between the adheres (completed questionnaires at both T1 and T2, N = 226) and the participants who dropped out in T2 (N = 31). This was conducted for all variables in the model.

3. Results

3.1. Differences between timepoints

COVID-19 events (t = 17.58, p < .001) and COVID-19 impact (t = 4.778, p < .001) were significantly different in T2 from T1, with higher mean and median for COVID-19 events in T2 than in T1, and with lower mean and median for COVID-19 impact in T2 than in T1 (see ).

Table 1. Demographics, social information and COVID-19 related details, among participants in Time 1 vs. Time 2.

3.2. Differences in variables between completers and non-completers

Several demographic factors significantly differentiated the women who dropped out from those who adhered. Lower levels of education (χ2 = 13.63, p = .009) and social support (t = 2.48, p = .019), as well as higher levels of financial difficulties (χ2 = 4.68, p = .031), emerged in the drop-out group than the adhering group (for all comparisons, see ).

Table 2. Differences between Time 2 completers and non-completers.

3.3. PATH analysis

The model fit indices suggested the model has an acceptable fit with the data (χ2 = 19.51, p = .07, df = 12, suggesting that fit to data cannot be rejected; RMSEA = 0.05, lower bound of 90% CI = 0.00, upper bound of 90% CI = 0.09; SRMR = 0.01, CFI = 0.96).

As expected, post-traumatic stress symptoms in T1 (estimate = 0.597, p < .0001) significantly predicted post-traumatic stress symptoms in T2. In terms of risk factors for PTSS in T1, a significant risk factor was the fear of COVID-19 reported by the women (estimate = 0.327, p < .0001), and a significant protective factor was support in T1 (MSPS, estimate = −0.274, p < .0001). Two additional significant risk factors for PTSS in T1 were unmarried/not in a relationship marital status (estimate = 0.198, p = .001), and COVID-19 reported impact on T1 (estimate = 0.309, p = .04). Medical complications during delivery or pregnancy were not significant predictors at T1 within this model.

As for the predictor factors for PTSS in T2, a significant protective factor was support in T2 (MSPS, estimate = −0.200, p = .007). A significant risk factor for PTSS in T2, in addition to PTSS in T1, is reported fear of COVID-19 in T2 (estimate = 0.133, p = .05). This is similar to the significant risk factor for PTSS in T1. Medical complications during pregnancy (estimate = −0.139, p = .003), appear to be a protective factor for PTSS in T2, but medical complications during delivery were not significant predictors. All significant pathways can be seen in the final model (; full regression results are presented in Table S1, supplementary materials).

4. Discussion

This longitudinal study aimed to explore maternal postpartum post-traumatic stress symptoms (PTSS) as they develop over time under the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. We used a hypothesis-driven model which was found to fit the study's data well. In this model, we suggested that the known ‘immediate suspects’ would affect maternal PTSS (medical complications during delivery or pregnancy, maternal physical and psychological disability, infant separation, and social support Grekin & O’Hara, Citation2014; Liu et al., Citation2021; van Heumen et al., Citation2018). Also, we hypothesized that COVID-related stress factors (COVID-19 related events, their perceived impact, fear of COVID-19, and changes in the birth plan) would contribute to the development of maternal postpartum PTSS. Within this model, however, some predictors (support, COVID-19 related fear and impact) evinced the expected relationship, and some did not.

Our data suggest that COVID-19-related events were more prevalent in T2 than in T1. This can be explained by the fact that over time and as the pandemic endured, participants were more likely to encounter COVID-19-related events. Therefore, a cumulative process occurred as individuals were exposed to additional COVID-19-related events. Interestingly, even though participants reported greater exposure to such events, the impact of events was reported as lower in T2 in comparison with T1. It could be that, as the COVID-19 pandemic remained active worldwide, individuals began adapting to the new way of life and to COVID-19-related events. Some of these events, which may have incurred a considerable amount of stress during the beginning of the pandemic, have to a certain extent been normalized in our everyday lives. This is in concordance with a recent study that found similar trends in the adaptation to the prolonged stressful event that occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic (Mækelæ et al., Citation2021).

As this was a longitudinal study, we examined the differences between the women who participated in T1 only, in comparison to those who remained in the study for T2 as well. It was found that the women who dropped out of the study had lower educational levels, lower social support, and more financial difficulties. This finding is similar to other longitudinal studies in which participants with a lower socioeconomic status dropped out at a higher rate (Goodman & Blum, Citation1996). A possible explanation for this is that participants with lower socioeconomic status are less available for undertaking tasks over and above their daily lives, especially considering the fact that our study was voluntary, and subjects did not receive compensation for their participation. This may also create a floor effect, explaining the lack of effect for salary and economic concerns on PTSS.

As expected, women who experienced PTSS in T1 were more likely to experience PTSS in T2. In previous studies, it was found that fear of COVID-19 was related to the development of PTSS (Villarreal-Zegarra et al., Citation2021). Similarly, in this study, it was found that women who reported a higher fear of COVID-19 were more likely to suffer from PTSS. In fact, we found that fear of COVID-19 was a consistent predictor for the development of PTSS in both T1 and T2, despite the dissipation of the subjective impact of COVID-19-related events from T1 to T2. Thus, PTSS in T1 fully mediated the effect of initial fear of COVID-19, COVID-19-related events impact on PTSS in T2. Taken together, this may mean that even though COVID-19-related events were subjectively perceived as less stressful in T2 than in T1 overall, and no longer predicted PTSS in T2, fear of COVID-19 was correlated to PTSS in a time-bound manner. This can be explained by the mechanistic relevance of fear processing to posttraumatic stress symptoms (Norrholm & Jovanovic, Citation2018; Zoellner et al., Citation2014). It, therefore, stands to reason that women with persistent fear may be also more susceptible to PTSS.

Furthermore, in this study, it was found that women who reported higher levels of social support were less likely to experience PTSS in T1 and in T2. This finding is in line with previous studies in which social support was found to be a protective factor for PTSS when experiencing trauma (Bryant-Davis et al., Citation2015; Zang et al., Citation2016). Marital status was a significant predictor of PTSS in T1 only, with PTSS in T1 fully mediating the effect of marital status on PTSS in T2. This suggests, that being partnered around birth was an important protective factor, however, over time, only the level of social support remained so. Therefore, it could be that marital status holds less impact past the initial period of motherhood.

Medical complications during pregnancy were found to be a protective factor for PTSS in T2. This finding may be explained by the fact that, especially in Israel, medical complications bring about a more frequent medical follow-up. Israeli women undergo extensive tests and examinations compared with the rest of the world, especially when it comes to high-risk pregnancy (for example, see Israeli Ministry of Health Guidelines (Monitoring of Pregnancy and Medical Examinations During Pregnancy, Ministry of Health) vs. United States common practices (Prenatal tests | March of Dimes)). In the new world of COVID-19 where many clinics and elective services were delayed or shut down altogether, women with high-risk pregnancies continued to have the benefit of thorough medical care and attention. Furthermore, as these women were exposed to the medical conditions during their visits to the clinic, it could be that they were familiarized with restrictions such as personal protective equipment, arriving at the date of birth having habituated to some of the COVID-19-related stressors which they’ve already encountered. Therefore, even though medical complications during pregnancy can act as a stressor, it may have been a protective factor in allowing a supportive medical framework as well as preparatory surroundings for COVID-19 healthcare restrictions. However, it is important to note that women who dropped out had more complications during pregnancy than those continuing to T2 (although not worse PTSS at T1), creating a potential ceiling effect. For those women who completed the second assessment, medical complications during pregnancy were not found to be a protective factor for PTSS in T1. This may be because, in T1, both COVID-19 conditions and the newly born infant were major life changes for paturients. In T2, these environmental conditions may have softened and therefore have been affected by such moderators to reach a lower PTSS level. It should be noted that not in concordance with our hypothesis, prior traumatic events in the last six months were not found to be associated with PTSS. However, this could be explained by few such reported events causing a ceiling effect. Economic status was not related to PTSS, but once again this could be explained by high dropout rates of low socioeconomic status participants, creating a floor effect. Future studies may wish to provide monetary compensation in order to curtail this.

5. Limitations

The current study benefits from being a multicentre study, which allowed a diverse population in terms of ethnicity, religion, or socioeconomic status. Furthermore, as this was a longitudinal study, it enabled the broad observation of variables as the COVID-19 pandemic proceeded and changed over time. Some of the maternal reports on demographics, obstetric and delivery data were validated against their medical records, therefore this data can be considered as more accurate. As most of the data was collected by self-report, social desirability should be considered as a limitation of this study. Also, limited causality may be inferred from the results of this study. Moreover, a substantial number of women did not answer the phone call for recruitment, which is an obvious recruitment bias, but we believe a smaller one than approaching self-selecting participants through social media as was done in recent studies (Berthelot et al., Citation2020).

6. Implications

COVID-19 has presented the world with some serious challenges, but also with great opportunities such as unprecedented financial assistance for healthcare growth (Micah et al., Citation2023). As such, this current study can contribute to the vision of maternal mental healthcare during the pandemic and as a whole. The current study's results present important information regarding maternal PTSS during COVID-19. We can assume that maternal PTSS during COVID-19 can be prevented when taking these results into account. In doing so, one of the most important factors to consider it the maternal fear of COVID-19. As PTSS during COVID-19 may affect not only the mental health of mothers but also maternal-infant bonding (Mayopoulos et al., Citation2021), these findings are valuable for both healthcare professionals and policy makers, as well as mothers’ families and loved ones. Particular attention should be directed at addressing COVID-19-related fear experienced by mothers and providing the adequate support accordingly. As Israel is a multicultural country with many internal conflicts and political issues, further studies should focus on the interaction between these conflicts and the mental health of mothers during COVID-19. Future research should focus on better understanding the characteristics of maternal fear of COVID-19 especially as the pandemic progresses over time.

7. Policy recommendations

If further lockdown periods are enforced in the future, governments should consider the fear factor and its relation to the population's mental health and especially maternal mental health. As fear of the pandemic was found to be an important factor in association with maternal PTSS, we recommend that healthcare professionals should provide psychoeducation regarding COVID-19 in order to try and minimize the fear of the pandemic as well as evidence-informed regarding fear-augmenting factors, such as limiting exposure to media.

Author contributions

Noga Shiffman – Data collection, writing the first draft, editing the final manuscript. Hadar Gluska – Data collection, editing the final manuscript. Yael Mayer – Study conceptualization and final draft review. Shiri Margalit – Data collection, Data analyses and write-up. Rawan Daher – Data collection, translation to Arabic of relevant materials. Lior Elyasyan – Data collection. Nofar Elia – Data collection. Maya Sharon Weiner – Data collection, collaboration between centres. Hadas Miremberg – Data collection, collaboration between centres. Michal Kovo – Data collection, collaboration between centres. Tal Biron-Shental – Data collection, collaboration between centres. Rinat Gabbay-Benziv – Study conceptualization, draft conceptualization, supervision of data collection. Liat Helpman – Supervision of and participation in manuscript conceptualization and writing, design of analyses, editing.

All authors provided critical feedback and helped shape the research, analysis, and manuscript. All authors gave their final approval to the manuscript and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (18.7 KB)Acknowledgements

Authors wish to thank Michal Tevet and Tal Malka for their assistance in data preparation and manuscript formatting and submission.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

All data may be available upon request contingent on the approval of institutional Helsinki committee.

References

- Ahorsu, D. K., Lin, C. Y., Imani, V., Saffari, M., Griffiths, M. D., & Pakpour, A. H. (2022). The fear of COVID-19 scale: Development and initial validation. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 20(3), 1537–1545. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-020-00270-8

- Aqeel, M., Rehna, T., Shuja, K. H., & Abbas, J. (2022). Comparison of students’ mental wellbeing, anxiety, depression, and quality of life during COVID-19’s full and partial (smart) lockdowns: A follow-up study at a 5-month interval. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13(April).

- Ausín, B., González-Sanguino, C., Castellanos, M. Á., & Muñoz, M. (2021). Gender-related differences in the psychological impact of confinement as a consequence of COVID-19 in Spain. Journal of Gender Studies, 30(1), 29–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/09589236.2020.1799768

- Ayers, S., Wright, D. B., & Thornton, A. (2018). Development of a measure of postpartum PTSD: The city birth trauma scale. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9, Article 409. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00409

- Basu, A., Kim, H. H., Basaldua, R., Choi, K. W., Charron, L., Kelsall, N., Hernandez-Diaz, S., Wyszynski, D. F., & Koenen, K. C. (2021). A cross-national study of factors associated with women’s perinatal mental health and wellbeing during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS One, 16(4), e0249780. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0249780

- Berthelot, N., Lemieux, R., Garon-Bissonnette, J., Drouin-Maziade, C., Martel, É., & Maziade, M. (2020). Uptrend in distress and psychiatric symptomatology in pregnant women during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica, 99(7), 848–855. https://doi.org/10.1111/aogs.13925

- Bryant-Davis, T., Ullman, S., Tsong, Y., Anderson, G., Counts, P., Tillman, S., Bhang, C., & Gray, A. (2015). Healing pathways: Longitudinal effects of religious coping and social support on PTSD symptoms in African American sexual assault survivors. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 16(1), 114–128. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2014.969468

- Gluska, H., Mayer, Y., Shiffman, N., Daher, R., Elyasyan, L., Elia, N., Weiner, M. S., Miremberg, H., Kovo, M., Biron-Shental, T., Helpman, L., & Gabbay-Benziv, R. (2021). The use of personal protective equipment as an independent factor for developing depressive and post-traumatic stress symptoms in the postpartum period. European Psychiatry, 64(1). https://doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2021.29

- Goodman, J. S., & Blum, T. C. (1996). Assessing the non-random sampling effects of subject attrition in longitudinal research. Journal of Management, 22(4), 627–652.

- Grekin, R., & O’Hara, M. W. (2014). Prevalence and risk factors of postpartum posttraumatic stress disorder: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 34(5), 389–401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2014.05.003

- Handelzalts, J. E., Hairston, I. S., & Matatyahu, A. (2018). Construct validity and psychometric properties of the Hebrew version of the city birth trauma scale. Frontiers in Psychology, 9. /pmc/articles/PMC6153334/?report=abstract. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01726

- Health IM. Israel Ministry of Health COVID guidelines [Internet]. 2020. https://govextra.gov.il/ministry-of-health/corona/corona-virus-en

- Hooper, D., Coughlan, J., & Mullen, M. (2008). Structural equation modelling: Guidelines for determining model structural equation modelling: Guidelines for determining model fit. Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods, 6(1), 53–60. Retrieved August 2, 2022 from https://arrow.tudublin.ie/buschmanart

- Liu, Y., Zhang, L., Guo, N., & Jiang, H. (2021). Postpartum depression and postpartum post-traumatic stress disorder: Prevalence and associated factors. BMC Psychiatry, 21(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-021-03432-7

- Mækelæ, M. J., Reggev, N., Defelipe, R. P., Dutra, N., Tamayo, R. M., Klevjer, K., & Pfuhl, G. (2021). Identifying resilience factors of distress and paranoia during the COVID-19 outbreak in five countries. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.661149

- Mayopoulos, G., Ein-Dor, T., Li, K., Chan, S., & Dekel, S. (2020). Giving birth under hospital visitor restrictions: Heightened acute stress in childbirth in COVID-19 positive women. Research Square. Retrieved August 2 2022, from https://www.researchsquare.com

- Mayopoulos, G. A., Ein-Dor, T., Dishy, G. A., Nandru, R., Chan, S. J., Hanley, L. E., Kaimal, A. J., & Dekel, S. (2021). COVID-19 is associated with traumatic childbirth and subsequent mother-infant bonding problems. Journal of Affective Disorders, 282, 122–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.12.101

- Mental Health Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Update. (2021). Retrieved August 2 2022, from https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/poll-finding/mental-health-impact-of-the-covid-19-pandemic/

- Micah, A. E., Bhangdia, K., Cogswell, I. E., Lasher, D., Lidral-Porter, B., Maddison, E. R., Nguyen, T. N. N., Patel, N., Pedroza, P., Solorio, J., Stutzman, H., Tsakalos, G., Wang, Y., Warriner, W., Zhao, Y., Zlavog, B. S., Abbafati, C., Abbas, J., Abbasi-Kangevari, M., … Dieleman, J. L. (2023). Global investments in pandemic preparedness and COVID-19: Development assistance and domestic spending on health between 1990 and 2026. The Lancet Global Health, e385–e413. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(23)00007-4

- Monitoring of Pregnancy and Medical Examinations During Pregnancy, Ministry of Health. Retrieved March 27, 2023 from https://www.health.gov.il/English/Topics/Pregnancy/during/examination/Pages/permanent.aspx

- Necho, M., Tsehay, M., Birkie, M., Biset, G., & Tadesse, E. (2021). Prevalence of anxiety, depression, and psychological distress among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 67(7), 892–906. https://doi.org/10.1177/00207640211003121

- Norrholm, S. D., & Jovanovic, T. (2018). Fear processing, psychophysiology, and PTSD. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 26(3), 129–141. https://doi.org/10.1097/HRP.0000000000000189

- Olde, E., van der Hart, O., Kleber, R., & van Son, M. (2006). Posttraumatic stress following childbirth: A review. Clinical Psychology Review, 26(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2005.07.002

- Ostacoli, L., Cosma, S., Bevilacqua, F., Berchialla, P., Bovetti, M., Carosso, A. R., Malandrone, F., Carletto, S., & Benedetto, C. (2020). Psychosocial factors associated with postpartum psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 20(1), 703. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-020-03399-5

- Prenatal tests March of Dimes. Retrieved March 27, 2023 from https://www.marchofdimes.org/find-support/topics/planning-baby/prenatal-tests

- Seng, J. S., Low, L. K., Sperlich, M., Ronis, D. L., & Liberzon, I. (2009). Prevalence, trauma history, and risk for posttraumatic stress disorder among nulliparous women in maternity care. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 114(4), 839–847. /pmc/articles/PMC3124073/. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181b8f8a2

- Su, Z., Cheshmehzangi, A., Bentley, B. L., McDonnell, D., Šegalo, S., Ahmad, J., Chen, H., Ann Terjesen, L., Lopez, E., Wagers, S., Shi, F., Abbas, J., Wang, C., Cai, Y., Xiang, Y.-T., & da Veiga, C. P. (2022). Technology-based interventions for health challenges older women face amid COVID-19: A systematic review protocol. Systematic Reviews, 11(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-022-02150-9

- Su, Z., McDonnell, D., Wen, J., Kozak, M., Abbas, J., Šegalo, S., Li, X., Ahmad, J., Cheshmehzangi, A., Cai, Y., Yang, L., & Xiang, Y.-T. (2021). Mental health consequences of COVID-19 media coverage: The need for effective crisis communication practices. Globalization and Health, 17(1), 1–8.

- Tzur Bitan, D., Grossman-Giron, A., Bloch, Y., Mayer, Y., Shiffman, N., & Mendlovic, S. (2020). Fear of COVID-19 scale: Psychometric characteristics, reliability and validity in the Israeli population. Psychiatry Research, 289, Article 113100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113100

- van Heumen, M. A., Hollander, M. H., van Pampus, M. G., van Dillen, J., & Stramrood, C. A. I. (2018). Psychosocial predictors of postpartum posttraumatic stress disorder in women with a traumatic childbirth experience. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9, Article 348. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00348

- Villarreal-Zegarra, D., Copez-Lonzoy, A., Vilela-Estrada, A. L., & Huarcaya-Victoria, J. (2021). Depression, post-traumatic stress, anxiety, and fear of COVID-19 in the general population and health-care workers: Prevalence, relationship, and explicative model in Peru. BMC Psychiatry, 21(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-021-03456-z

- Visser, M., & Law-van Wyk, E. (2021). University students’ mental health and emotional wellbeing during the COVID-19 pandemic and ensuing lockdown. South African Journal of Psychology, 51(2), 229–243. https://doi.org/10.1177/00812463211012219

- Xiong, J., Lipsitz, O., Nasri, F., Lui, L. M. W., Gill, H., Phan, L., Chen-Li, D., Iacobucci, M., Ho, R., Majeed, A., & McIntyre, R. S. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 277, 55–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.001

- Zang, Y., Gallagher, T., McLean, C. P., Tannahill, H. S., Yarvis, J. S., & Foa, E. B. (2016). The impact of social support, unit cohesion, and trait resilience on PTSD in treatment-seeking military personnel with PTSD: The role of posttraumatic cognitions. Journal of Psychiatric Research.

- Zimet, G. D., Dahlem, N. W., Zimet, S. G., & Farley, G. K. (2010). The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Journal of Personality Assessment, 52(1), 30–41. Retrieved August 2, 2022 from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1207s15327752jpa5201_2.

- Zoellner, L. A., Pruitt, L. D., Farach, F. J., & Jun, J. J. (2014). Understanding heterogeneity in PTSD: Fear, dysphoria, and distress. Depression and Anxiety, 31(2), 97–106. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22133