Abstract

Until recently, café and restaurant design in modern Hong Kong has been characterized by closed facades that keep cooled air inside in the hot and humid subtropical climate, and interiors that allow limited visual contact with the street and with the kitchen. A new tendency of openness, however, has appeared in specialty coffee shops that have opened over the last decade. In this article we study this phenomenon, querying its significance in relation to the social dimensions of design trends and ideas about openness. The article is based on field studies of over 80 local specialty coffee shops in Hong Kong from 2020 to 2022 and includes analysis of facade and interior design from participant observation studies, photographs and interviews with store owners focusing on the factors that shape design intentions. Our analysis identifies characteristics of open coffee shop facade and interior design and discusses these in relation to openness as a conceptual paradigm in urban research and design studies. Our findings highlight the significance of international and local trends, social media visual cultures, and sustainability issues as considerations in open facade and interior design.

Introduction

In contrast to many other parts of the globe, coffee culture in Hong Kong is relatively young. Coffee drinking originated in Ethiopia, spread to the Arab world in the 15th century, and arrived in Europe at the beginning of the 17th century. Coffeehouses began appearing soon after this (Broadway, Legg, and Bertossi Citation2020) and have since that time served as informal public gathering places, where people meet, establish ties, and form communities (Broadway and Engelhardt Citation2021; Oldenburg Citation1989). Habermas (Citation1991, cited in Broadway and Englehardt 2021) traces the origin of the so-called public sphere to the coffeehouses of 17th-century London, where citizens openly debated the affairs of the day, and attempted political influence. The nature of coffee shops has changed considerably, influenced by the growth of coffee as a commodity, globalization and consumption trends, but some elements of the early formats, including sociality, remain and are influenced by design.

Not until the 1950s, under British influence, did coffee shops begin to appear in Hong Kong. Today it has developed into one of the industry’s leading centers, offering quality, fair trade, sustainable, aesthetic and highly specialized coffee experiences – characteristics of the current “third wave” of coffee consumption (Tucker Citation2017). While the exact number of coffee shops is difficult to pinpoint, informal counts by local coffee enthusiasts suggest that in 2021 alone, a year in which many retail businesses struggled or closed, between 220 and 300 new coffee shops opened in the city (Barber and Münster Citation2022). In contrast with past experiences of consumers discovering and choosing cafés based on their visual prominence and neighborhood proximity (e.g., Oldenburg Citation1989), social media is an important contributor to this phenomenon and Instagram (IG) is in Hong Kong the most commonly used platform to promote, discuss and share information about coffee shops. Photos of coffee shops posted on IG reveal many aspects of coffee culture in Hong Kong including carefully designed and visually appealing spaces. A common coffee shop design is apparent which features partially or fully open facades through which customers can see out and people in the street can see in. Interior designs are mostly open-concept, with staff working behind a counter in close proximity to customers seated nearby (Barber and Münster Citation2022). These open designs are distinctive because they mark a departure from those of earlier cafés and food and beverage establishments in Hong Kong, where transparency between street and interior, and between customer seating and kitchen areas, was often limited. Unlike the older café format, which could be considered Hong Kong first wave, the second wave cafés and coffee shops like Starbucks and Pacific Coffee that opened in the 1990s and early 2000s were often in shopping malls or other busy commercial areas. Other small “upstairs cafés” during this period operated on upper floors of commercial buildings with no street presence. Spending time in coffee shops is a leisure experience that offers a break from the city. But many of the new coffee establishments in Hong Kong seem to invite the city inside.

This study identifies design features that create a sense of openness in interiors and facades in recently opened coffee shops in Hong Kong and discusses their spatial effects. Empirically, our analysis considers approximately 200 IG posts along with data gathered through participant observation activities conducted at 80 coffee shops. Through analysis of coffee shop designs, we identify and map design tendencies and discuss them in relation to social currents in Hong Kong in which openness figures centrally. Through interviews with store owners, we attempt to access the motivations and intentions behind these designs. The paper discusses the findings from the observation studies and the interviews in relation to the theories on openness in designed facades and interiors, alongside more general insights concerning openness, particularly as it relates to urban economies.

The remainder of this paper is organized into four sections. First, background information is presented including the contemporary setting in Hong Kong, the historical development of café design in the city, its expanding coffee culture, a brief review of coffee shops as a research topic, and an introduction to aspects of openness drawing on various interdisciplinary conceptual sources relevant to design. Second, the methodology is described including case selection, in situ participant observation, and the use of store owner interviews. Third, our findings are presented in two sections, one focusing on design features related to facades, and the other on interiors. Fourth, we sum up and discuss the significance of findings and present concluding remarks.

Background

Open and closed Hong Kong

Openness is one of the common descriptors of Hong Kong, along with inequality, accompanying its role as a global finance capital and gateway between the west and China (Chiu and Lui Citation2009; Wissink, Koh and Forrest Citation2017). Hong Kong’s airport is one of the world’s most important cargo hubs, playing an important role in the territory’s economy (McNeill Citation2014), and under normal conditions passenger flights connect the city with myriad places around the world. The border is relatively open, compared with that of mainland China and many countries in the region, with tourist visas available on arrival to holders of many passports. The open border and “free” economy contribute to a cosmopolitan and fast-paced atmosphere. The COVID-19 pandemic, however, resulted in severe disruptions to mobility and daily life, a form of closure, coinciding with a period of political change.

Beginning in early 2020 travel restrictions were introduced including requiring arrivals to undergo a mandatory hotel quarantine of up to 21 days. Non-Hong Kong residents were banned from visiting for over two years. These and related restrictions saw the number of airport arrivals drop to around 200 per day in early 2022. Several airlines suspended flights voluntarily for an indefinite period. Within the city restrictions on businesses such as restaurants, beauty parlors, as well as gyms and sports facilities, were introduced to control the spread of the virus. Although Hong Kong did not have a full-scale lockdown like many cities, the impact of mitigation measures was severe due to Hong Kong’s high level of dependence on connections with other places, particularly mainland China. In spite of Hong Kong’s status as a Special Administrative Region in China, a controlled border with neighboring Guangdong province is maintained and, with restrictions only beginning to ease in mid-2022, Hong Kong endured a period of extreme isolation. Coffee shops have thrived during this time. The reasons for this trend are complex but in part reflect the pandemic condition – the economic downturn resulted in lower rents which allowed entrepreneurs to open small businesses, and Hong Kong residents sought local experiences in the place of travel.

Prior to the pandemic, in 2019 Hong Kong experienced a prolonged period of civil unrest prompted by a proposed bill that would allow the extradition of criminals to mainland China. Protests escalated over several months, with frequent confrontations between police and protesters, culminating in university campus occupations ending in siege-like scenes (Bennett, Barber and Iaquinto Citation2020). The COVID-19 virus arrived in Hong Kong at the tail end of these protests and, with pandemic measures in place, the government introduced a controversial National Security Law and clamped down on dissent.

Hong Kong’s extreme density is one effect of its openness. Experienced on the ground, streets can feel enclosed by buildings and the sky can seem distant. In this city “without ground” (Frampton, Solomon, and Wong Citation2012) pedestrians are often ushered above or below ground and into shopping malls (Barber Citation2020). Public open spaces punctuate the urban landscape and are often busy, especially in fine weather. Country parks encircling the city offer a different kind of open space but have also been crowded during the pandemic with people seeking to escape. Outlying islands and beaches have also drawn visitors but the latter were closed for long periods under covid regulations.

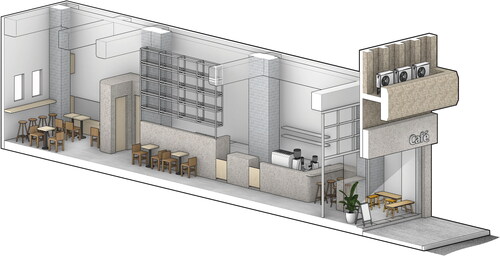

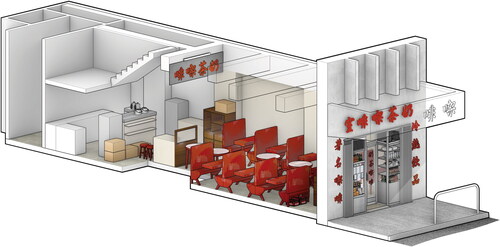

Hong Kong’s specialty coffee shops offer a locally grounded form of open design. These small, independent businesses have appeared throughout the city, often in mixed use residential areas rather than busy, touristy commercial districts, in spaces with lower rent (South China Morning Post Citation2021). Their facades commonly feature open areas or large windows allowing passersby to look in, and customers to look out. Earlier iterations did not have these open facades. Traditional first wave cafés, like Bing Sutts (“ice rooms”) and Cha Chaan Tengs (“tea restaurants”) (Lam Citation2020, BBC Travel Citation2020) that serve drinks and hot meals cover their front windows with food displays, menus, and promotions (). These businesses rely on fast table turnover rates, and having customers decide what to order before they enter reduces the time customers spend in the restaurant thereby increasing revenue. Other effects of the blocked windows and closed doors are that customers inside get a break from the often busy and noisy streets outside, and that air-conditioned air is kept inside and warm and humid air outside. Second wave coffee shops, of which there are still many in the city, often belong to corporate chains like Starbucks and Pacific Coffee. They have larger and more conventional shop fronts on commercial streets and in shopping malls, often with large windows but never open to the street.

Coffee shops as research topic

Coffee is the second most important globally traded commodity after petroleum, and its consumption has generated increasing interest on the part of researchers (Roseberry Citation1996; Ferreira, Ferreira, and Bos Citation2021; Shiau Citation2016; Broadway and Engelhardt Citation2021). Coffee consumption cultures are both geographically specific and influenced by interactions across borders (Tucker Citation2017). The development of coffee consumption is often described retrospectively in terms of waves. The first wave was characterized by inexpensive mass consumption (e.g., instant coffee, at home or in unembellished café formats), the second wave was marked by the success of major brand-name coffee shops that capitalized on leisure aspirations by offering higher quality products and more comfortable spaces (e.g., Starbucks), and the third wave is associated with various features of the specialty coffee market, including fair trade, the craft of baristas and carefully branded and design-conscious independent businesses (Tucker Citation2017; Ferreira and Ferreira Citation2018).

Spaces of coffee consumption are of interest as places of social interactions (Oldenburg Citation1989), the specialized craft of baristas (Piercy Citation2018) and consumption of store atmospheres (Kotler Citation1973; Smith Citation1996; Shiau Citation2016). Kotler (Citation1973) describes how design elements in stores influence consumers’ perceptions of product and service and argues how the atmosphere of a place can in some cases be the primary product. In an ethnographic study in Taiwan, Shiau (Citation2016) found that patrons of Starbucks are consuming designed coffee shop spaces in ways that challenge cultural norms. Raised counters, sightlines between baristas and customers, and large windows were already a feature of Starbucks coffee shop designs in the 1990s (Smith Citation1996). These and other marks of openness have been further emphasized in Hong Kong’s coffee shops. We argue that studying them can contribute new insights to existing work on coffee shops as social spaces of consumption reflecting local and extra-local networks of influence as well as local entrepreneurial practices and consumer cultures.

The open design format that we have identified in the third wave coffee shops (, ) contrasts with that of older local cafés () but recalls the traditional design of many small shops in Hong Kong, that are entirely open to the street, allowing customers to select items without entering and providing natural light and air circulation (). In these traditional shops the open area is used for product display and not for consumers enjoying the purchased product and the atmosphere.

Aspects and sources of openness

Openness is a concept that travels easily between metaphorical and material registers. Ideas about openness find their roots among philosophers of pedagogy and semiotics for whom it is both socially progressive and intellectually generative. For Freire, teaching and learning with a spirit of openness is a way to approach the “Other” (Roberts Citation2011). In concrete terms this could mean being responsive to new ways of learning. For Eco (Citation1989), openness in interpretation means not fixing solid meanings. Matched with words like innovation and flexibility, openness has become a paradigmatic term in the lexicons of planners and policymakers, keen to compete in the fast-changing registers of tech and knowledge economies (Lundgren and Westlund Citation2017). Lorne (Citation2020), quoting Goss (Citation1996), points out the long association between architectural openness and social inclusion, but also its limits.

Metaphors of openness as connectivity and experimentation are concretely applied in design where a new paradigm embraces the same type of “open source” ethos for hardware that has long been associated with software development (Aitamurto, Holland and Hussain Citation2015). “Open-concept” design, referring to building interiors with fewer walls and doors, has become common in a variety of settings, with implications for social relations, productivity and privacy (Attfield Citation2002; Dowling Citation2008; Dowling and Power Citation2012; Kim and De Dear Citation2013). Open plan offices may increase productivity by facilitating interactions, but they can also lead to distraction and reduce workplace satisfaction (Kim and De Dear Citation2013). Moreover, they may be motivated partly by managerial concerns like surveilling employees and saving costs. They are especially popular with creative industries, where they are understood to be the ideal setting for new forms of work. Co-working spaces offer open plan designs in a format that introduces temporal and spatial flexibility, further disrupting the traditional office setting: “open-ended design encourages fluidity and flexibility, creating a sense of ownership for members able to rearrange the architectural space continuously according to their changing needs” (Lorne Citation2020). There is hence an assumption that physically open spaces lead to collaboration and innovation, hallmarks of the neoliberal knowledge economy.

The social context and effects of open-concept home interiors, generally referring to combining kitchen and living/dining areas has been acknowledged by scholars. For Attfield (Citation2002), the open-concept post-war British home encapsulated modern living, incorporating notions of “adaptability, mobility and change.” Dowling (Citation2008), writing about Australian domestic spaces and lives, highlighted the meaning of open-space design for women and families. Open-concept living spaces allow for visual contact between rooms which makes multi-tasking – cooking or cleaning while child-minding – easier. They also transform both children’s and adults’ lives through contact and exposure that comes with both visibility and a reduction of privacy.

Open-concept residential interiors are relatively new in Hong Kong and have some features that are related to similar trends in retail design. Traditionally the kitchen in Hong Kong apartments, even if very small, is in a separate room. Until recently this was also required by the Building Code, which stipulated that home kitchens must be separated from other living areas by a fireproof door and include a window for ventilation. In 2012 the code was changed, no longer requiring a door, only fireproof walls around the cooking area (Factwire Citation2020). This change coincided with the rise of tiny so-called “nano” flats, which maximize space by featuring open-concept design, often in 200 square feet or less. Similarly, coffee shops bring food and drink preparation into the view of customers, breaking with long-standing norms.

While the open designs of Hong Kong coffee shops are context- and industry-specific, themes of openness in other realms of interior design, such as offices and homes, as well as the celebration of openness as an intellectual aspiration, are relevant. All of this points to the transformative potential of openness, which may be experienced in different ways, as well its capacity for being capitalized upon as a material setting that creates an appealing atmosphere.

Methods and analysis

The study is based on qualitative mixed methods research using several datasets, including IG posts, photos and notes from participant observation activities, and semi-structured interviews with store owners. Data were coded and analyzed with a focus on design features and the intentions motivating design decisions.

Mixed methods data collection

With Instagram as the most used platform to promote, discuss and share information about coffee shops, we began by identifying, browsing and following Hong Kong related coffee shop-related hashtags in December 2020. Our first data set features more than 200 IG images of local independent and small-chain coffee shop facades and interiors posted by store representatives or visitors between December 2020 and September 2022.

Participant observation was carried out at 80 of the coffee shops identified on IG during casual and more structured visits between March 2020 and September 2022. The participant observation activities helped us to gain insight into the real-life context of the coffee shops and the experience of their design features from a consumer perspective, and brought us in contact with store representatives. Our second data set features our own photos, videos and field notes from these observations. Semi-structured interviews were subsequently carried out with nine store owners. This small sample is not intended to represent all Hong Kong coffee shops but rather to provide insight into considerations and intentions behind the store design, and in particular the open facades and interiors. The interviewees played an active role in designing their shops and in some cases didn’t employ professional designers. They are therefore well-positioned to speak to motivations concerning store design. The interviews included questions regarding the ongoing wave of coffee shop openings in Hong Kong, design trends, and reasons for including open features in facade and interior design ().

Table 1. Details of the nine shops where interviews were carried out.

Analysis

With a specific focus on the facade and interior design features, physical spaces and images were analyzed, coded and themes were identified.

The analysis revealed that the open design was significant for a specific type of store: individually designed, locally owned specialty coffee shops located in older neighborhoods. Larger, more corporate third-wave chains do exist, and these stores make use of similar design features as the individual stores but are often bigger and located in commercial areas. The analysis helped us identify the type of business and the features that contribute to a sense of openness in the design, including the materials and transparency. The eye height views from inside and out and from outside and in were considered, alongside space management and layout, including the position of the bar and seating options.

In the anthropological tradition – here applied for an interdisciplinary consideration of design – observing by participating also allowed us to study the environmental context of the coffee shops such as the neighborhood, the location on the street, and neighboring businesses. As participant consumers we were attentive to the behavior of staff and customers, which allowed us to assess the open design features in relation to a range of contextual factors.

Identification of design characteristics and behaviors in the stores led to analysis of the qualities of the open design from a consumer perspective, and the interviews with nine store owners confirmed our observations and also provided new insights about the factors motivating open design decisions.

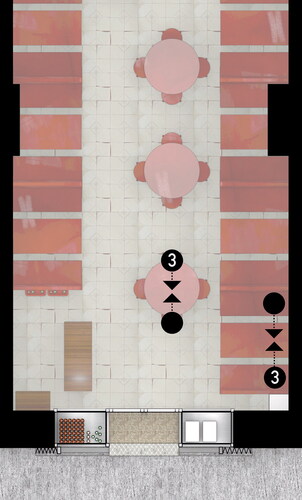

Findings

In this section findings from the observation studies and interviews are presented and discussed. We will first describe the “Exterior” and “Interior” design features that were used to create the feeling of openness. A sense of open and transparent facade designs – their prominence, aesthetic, features, use and portrayal – and of the open bar areas, was arrived at through a visual content analysis of our two first data sets. This included consideration of the context, possible design intentions, as well as the composition of the images and the audience effects of the IG images (Rose Citation2016). Based on the analysis of form and features, a typology of a Hong Kong coffee shop was created (). This typology does not represent an actual store but is based on design characteristics identified in the analysis. It serves as a reference illustration in the remaining parts of the paper. Discussion of insights from the interviews reveals the complexity of identifying clear intentions and sources of inspiration for the open designs, as well as unanticipated consequences that belie the attractive atmospheres they create. was created to visualize differences between older traditional cafés in and modern specialty coffee shops in Hong Kong.

Exterior design features

Location and architecture

Newly opened coffee shops are typically located in older mixed used residential areas, which are often quieter, with less traffic than commercial districts. These locations offer more pleasant interactions between interior and exterior than those on busy streets. The shops are typically located in renovated ground floor spaces in buildings dating from the 1960s and 1970s. The spaces are deep but narrow with limited store frontage. Building facades are the visual surfaces of buildings, revealing style and structure. They contribute to the image of city districts and streets, while also conveying information about building occupants, like businesses. They are also the interface between exterior and interior (Askari and Dola Citation2009).

Store facade

Store facades, including windows, entrance area, and branded design features, are especially important for retail brands. They provide distinctive visual anchors in streetscapes and suggestions of what consumers will find inside, both in terms of atmosphere and products (Haug and Münster Citation2015; Kent and Petermans Citation2017). Open facades are common in various types of retail businesses and may serve to attract interest from the street. In coffee shops they also offer customers a vantage point on the city. We identified four types of open facades which sometimes appear in combination: (A) fully open facades, where a metal shutter reveals a fully open facade when the shop is open (), (B) full size unblocked glass facade combined with glass door, often a sliding glass door that is partially or fully retractable (), (C) full size folding glass panels that allow the facade to be open, partly closed or closed (), (D) windows in eye height combined with glass door ().

Outdoor seating

Recessed facades, like that shown in Photo 6, where the glass facade is recessed from the street allow the creation of a small outdoor seating within the premises of the store. Unlike the former café formats () the windows are never blocked. The interior is visible from the outside, and from the inside, the seats are arranged so that customers can look out. This arrangement dissolves the boundary between the private space of the store and the convivial and anonymous space of the street, but it also acts as a threshold that reinforces this distinction. Many passersby, especially in older and poorer neighborhoods, would not patronize these businesses. And, likewise, for customers visiting coffee shops from other areas of the city, the neighborhood may take on the quality of spectacle of the unfamiliar. This suggests a movement of the flaneur’s gaze, from that of a subject strolling the sidewalk to a leisure consumer – sitting, sipping and watching from inside (Smith Citation1996).

Design intentions, exterior

When asked about the open facades of their businesses, store owners often did not clearly articulate design intentions. One store owner (TPFootnote 1 ) said, “We never really thought much about the design”, and another (SO) said, “I didn’t really understand design much back in the days [when I opened the store].” However, it was clear that they saw open facades as important for the success of their businesses, as one respondent explained: “the outdoor part is very popular” (DH). She went on to explain that if it were practical, the whole business would be outside because sitting on the street provides a special perspective on the neighborhood. Another store owner mentioned wanting to make the coffee shop inviting for people with dogs and thought that offering outdoor seating would be a good solution. In Hong Kong dogs are popular among middle and upper classes who have space and money to spare.

The two-way visibility of coffee shop facades was touched upon in several interviews. At one store, the facade design was completed by the former owner, but the interviewee explained that they probably shared some perspectives on design: “wanting to create an open space for all and also welcome all to look into our space" (OP). Some store owners related the openness of the facade to the value of interacting with the community. When asked about the reason for the open facade, one store owner said that “community and collective memory are some of our brand’s values” (HW). This suggests an effort to position the business within the city’s histories. Other environmental qualities were also mentioned. For instance, one store owner said, “sunlight is very important, and we wanted to have more sunlight coming in, so an open, transparent element was designed here” (TP).

Other store owners mentioned drawing some inspiration from visual social media platforms like Pinterest and Instagram. A respondent explained that they were not trained in design and created the design concept by exploring online and seeking inspiration while traveling abroad. Another said they chose the open facade: “Because Instagrammers like this style” (ME). He explained that Instagrammers often take photos in front of the shop, and that people like to sit in the open window and watch the street. On the other hand, he pointed out that the open facade design is problematic because of the loss of air-conditioned air. He explained: “it’s ok in the spring, but in summer it will be too expensive to cool down the shop with the windows open.” Another store owner, whose facade is fully open said: “We did it because Store SO has this” (AO). Store SO is a popular coffee shop which was among the first to implement an outdoor area. Store SO has outdoor seating but a glass facade and a sliding door keeps the air-conditioned air inside. The fully open facades pose an energy consumption dilemma with environmental and monetary consequences, a problem shared by other establishments which may intentionally use cool air to try to entice customers. Elsewhere this has been regulated due to energy waste (Brasuell Citation2015). Another difference between SO and AO is the location. Both have outdoor seating, but SO is located on a street with light sidewalk use and light vehicle traffic, and AO is on a street with moderate sidewalk use and moderate to heavy vehicle traffic, leaving the outdoor space less noisy and more comfortable. The completely open facade of AO coffee shop, on a busy and noisy street, suggests that for some establishments design aesthetics may take precedence over environmental considerations.

Several store owners referred to Australia and Japan, places with different climates, as sources of inspiration for the coffee shop design: “I got influenced a lot by the Australian style of cafés. Because in Australia, you would have the time to talk to the barista, and at least maybe with the customers. It is very open” (CC). This comment seems to imply a double meaning of openness as a social characteristic in addition to open format design. Another says: “Australia… they have amazing coffee shops. That’s where the coffee scene is” (SO). Ironically, Shop SO’s open design and outdoor seating were also not the result of a premeditated vision. The owner explained that before the shop opened, he had never seen these open niches before, but his father suggested including one in the design. Initially he didn’t understand the value of the open area, but his father insisted and he gave in thinking that it could be a nice place for smokers. The outdoor area turned out to be successful: “It turned out to be not just a smoking area, customers like outdoor seating” and now, he continues, “most coffee shops have this”. Outdoor seating is still rare in Hong Kong because of the climate, the noise and pollution, but it is a growing trend, perhaps drawn from other locales. The outdoor space was eventually used for other purposes, including live small jazz concerts for patrons and passersby in the streets. The open facade design of SO may have been somewhat accidental, but the store owner has realized its attractiveness. This is the type of “active” street level activity has been shown by Gehl and Svarre (Citation2013, 104) to be eye-catching and draw in passers-by.

Interior design features

Window and entrance area

Openness is also apparent in the coffee shop interiors. In these narrow, deep spaces, an open facade design is an easy way to bring natural light in, provide air circulation and increase visibility to and from the street. The façade is often the only place where natural light can enter. The ceilings in these structures are typically high and open, and allow for a deep inflow of light ().

Bar area and seating

Most shops have an open bar area, behind which the barista and other staff work. This multi-purpose area is where the coffee and food are prepared, and where the ordering and payment transaction take place. The bar area closest to the entrance is allocated for the barista and is totally open, allowing the barista to face the customers when entering the store. Space for food preparation is often towards the rear. While the area between kitchen and customer area is open, structures like shelves or a half wall are often installed, providing semi-transparent visibility to the kitchen. The bar takes up the space along one wall, leaving, if the width of the store allows it, a narrow space for a row of chairs, counter seating or small tables along the opposite wall ().

The seating surrounds the bar area and the space is open, apart from a small toilet room in the back of the store. Seats in the windows are popular – either with stools facing the street or with chairs and small tables. In the back of the store there is usually a quiet seating area.

Tables and chairs are often placed so that customers have a view. The most popular seats are observed to be the seats facing the outside and seats facing the barista ().

Design intentions, interior

When asked about the intentions behind the open interior design, owners referred to the ability to show the coffee making and communicate with customers. One said, “it’s also important for guests to be able to see the bar, because I make coffee here” (DH). Another store owner mentioned that the open design was already established when she took over the place, but she liked it and decided to keep it, explaining, “The guests can watch the staff doing things, preparing food, for example, and this could create a special feeling of connection. Especially when it comes to making coffee, people like to see how it is done, to see the process, and to watch how we do, for example, the latte art” (CW). These comments highlight the craft of the barista (Piercy Citation2018) and suggest that the coffee bar resembles a stage where they perform. But it is not just about seeing the coffee being made, but also about communication: “if you are a guest sitting here, I can communicate with you.” Several store owners mentioned communication with customers as a value supported by the open design, “We like to chat and communicate with our guests”, the store owner of DH said, another one echoed this: “I prefer having them sit around the bar so that we get that conversation. I could get to know them and ask what brings them to this neighborhood” (SO), and continued, “I always wanted to know each and every customer’s background, like, whoever they are. They tend to bring really interesting stories. And I always try to connect people.” However, he also acknowledged that customers are different, and they have different preferences, which is the reason for the varied seating options “customers can come in and choose. If they want to sit by themselves, they can just sit away from the bar, or further in the back or outside.” In reality most seats face the interior space and thus position the customers, often seated alone, to see the activities in the café, both behind the counter and in the seating area (), or in the street (). This contrasts with older café formats, where circular and rectangular tables encourage interaction within a group of diners, facilitating food sharing which is typical in Hong Kong ().

This emphasis on communication and interaction mirrors some of Dowling’s (Citation2008) ideas about residential design, and also the open plan office or co-working space where collectivity is embraced as a value (Lorne Citation2020). Work in an unwalled space can very quickly become interactive multi-tasking. This can alter the atmosphere of the coffee shop for consumers, while also highlighting and enlivening the work of the baristas. On the other hand, the open bar and kitchen mean that staff are always “on,” with their movements and activities visible at all times. This may force them to keep the workspace differently, perhaps tidier, than it might be if hidden from view.

The interactive atmospheres of coffee shops offered an antidote to the isolation that many faced while working and studying from home during the pandemic. Meanwhile, the references to elsewhere, like Japan or Australia, created appealing atmospheres in the place of impossible travel.

Discussion

The open plan designs of Hong Kong’s coffee shops are visually appealing. They translate well in photographs and entice patrons with views from the outside in and inside out. Our research reveals a complex range of factors that have influenced design intentions. In many cases such open designs, especially facades, are selected as a result of trends that may be traced to origins outside of Hong Kong, in slightly less humid or hot climates. Established coffee shops in Hong Kong have also become models emulated by other newer shops leading to a recognizable local coffee shop design repertoire that is tending towards homogenization as more shops appear. Open facades and interiors are attractive, but also functional in specific ways – providing a space for smokers or dog-owners, for instance, and allowing the customers to observe the process of making coffee and interact with staff. Two consequences may be raised for further consideration. First, not all locations are well-suited for fully open entrances and facades in Hong Kong due to noise and roadside pollution. Coffee shops that open on high traffic streets with such designs may be proximate to noise that is disruptive to both customers and staff. Hong Kong’s streets are busy, and this could be taken into account in the early design process. Some of the neighborhoods where coffee shops have opened are changing rapidly, which may result in rising rents and displacement of more traditional retail businesses. Second, open entrances, and fully open facades have environmental consequences. Air conditioning is ubiquitous for a large portion of the year, and open doors and windows that let cool air escape when air conditioning is running (a practice we observed at some coffee shops) are both cost- and energy-inefficient. Such willfully unsustainable design and retail space management has been banned in New York City, where businesses can be fined for trying to entice customers by blasting cool air into the street (Brasuell Citation2015). In Hong Kong coffee shops are not the only businesses doing this, but it may contradict other environmentally sustainable practices. A two-level facade, like in Photo 6, with a glass facade between café interior and outdoor seating area seems to be better suited to meet both the expectations of outdoor seating and the option to keep cooled air in the café.

Conclusion

The explosion of specialty coffee culture in Hong Kong, manifest in the opening of hundreds of coffee shops over the short span of a few years, has coincided with a period of great change in the city, and globally. The civil unrest of 2019 and the COVID-19 pandemic led to the closure of Hong Kong’s borders and the severe limitations on several fronts, from trade and tourism to work and everyday activities. It is with some irony, then, that coffee shop designs are deliberately open. All of the more than 80 shops considered in our study, open their facades to the street. They create views in and out, sometimes through glass; they also allow noise and air to pass freely between the interior and exterior. Our research suggests that this trend, while achieving some desirable effects in terms of atmosphere, has been pursued as a result of an accidental process of discovery. It is appealing because it makes the city, especially quieter neighborhoods that offer a taste of different slices of everyday life and street scenes, accessible to coffee shop patrons, and makes the coffee shop visible to the city. Open interiors break down the barriers between staff and customers, highlighting the work of staff baristas, the coffee and contributing to the social atmosphere of coffee shops. These design trends have implications that reflect some aspects of theories of openness, including creating an atmosphere that encourages collaboration. Elsewhere similar designs have been associated with the neoliberal knowledge economy (Lorne Citation2020).

Since our methods included a mixture of observation, photo analysis and interviews, we must add a disclaimer that the findings presented are tentative, rather than broadly generalizable. Research that scales up in sample size, asking not only coffee shop patrons and staff, but also neighborhood residents, about their perspectives on coffee shops as presences in the street and as agents of change, could further advance the study of this phenomenon.

Photo 1, left, an older type of café known as Bing Sutt. Facades are blocked–either with the traditional folding metal shutters when closed, or by product display and signage when open–and therefore do not reveal the vibrant atmosphere inside (Photo by author, 2021).

Photo 2, right, an older café with a product display outside to attract customers and facilitate take-away sales, while at the same time blocking the view to the interior. (Photo by author, 2021).

Photo 3, right, example of a third wave of coffee shop with an open facade where customers can enjoy the purchased product and neighborhood atmosphere. (Photo by Author).

Photo 4, left, example of traditional shop with fully open facade intended for product display, allowing customers to select items without entering and providing natural light and air circulation (Photo by Author).

New coffee shops with open facade designs (Photos by author, 2021).

Photo 5 top/left: a fully open facade. When the metal shutter is open, a fully open facade is revealed.

Photo 6 top/right: a full-size unblocked glass facade with sliding door in glass, and a recessed niche for outdoor seating. The outdoor seating is within the premises of the store and a recessed glass facade divides the outdoor and indoor area.

Photo 7 bottom/left: facade with folding glass doors, which makes it possible to close or partly close the facade.

Photo 8, bottom/right: a facade with unblocked windows in eye-height and a glass door.

Photo 9-10, Stores are typically deep, narrow, with high ceilings, and open or transparent facades allowing for inflow of light.

Illustration 1. Typology of specialty coffee shop in Hong Kong based on analysis of images and observation studies.

Illustration 2. Traditional café format in Hong Kong based on analysis of images and observation studies.

Illustration 3, left. Specialty coffee shops layouts with indication of (1) visual connection between customers and baristas and (2) between the interior and street.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Lachlan B. Barber

Lachlan B. Barber was formerly an Assistant Professor in the Department of Geography at Hong Kong Baptist University. A specialist in urban and cultural geography, Lachlan has published widely on topics related to urban landscapes, heritage conservation and mobilities in East Asia and Canada. His interest in coffee culture stems from observations on shifting landscapes of consumption, including in conserved historic buildings, during his time in Hong Kong. Lachlan holds a PhD in human geography from the University of British Columbia and worked in Hong Kong for 7 years. Email: [email protected]

Mia B. Münster

Mia B. Münster is a Research Assistant Professor at PolyU School of Design in Hong Kong. She earned her PhD from Copenhagen Business School, and holds master’s degrees in both Architecture and Design. Mia has over 20 years of professional experience as a Designer and Creative Brand Manager in the field of retail and hospitality design. Mia has published research on optimization of design processes, on the designer’s role in the transition to circular economy; and on the effect of designed spaces on their users. She is currently conducting cross-cultural studies of the design and culture found in coffee shops. Email: [email protected]. linkedin.com/in/miamuenster

Notes

1 All quotes are from store owner interviews. The letters refer to the abbreviated shop name from Table 1.

References

- Aitamurto, Tanja , Dónal Holland , and Sofia Hussain . 2015. “The Open Paradigm in Design Research.” Design Issues 31 (4): 17–29. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43830428. doi:10.1162/DESI_a_00348.

- Askari, A. H. , and K. Dola . (2009). “Influence of Building Façade Visual Elements on Its Historical Image: Case of Kuala Lumpur City, Malaysia.” Journal of Design and Built Environment 5 (1): 49–59.

- Attfield, Judith. 2002. “Moving Home: Changing Attitudes to Residence and Identity.” The Journal of Architecture 7 (3): 249–262. doi:10.1080/13602360210155447.

- Barber, Lachlan B. , and Mia B. Münster . 2022. “#Hkcafe: relational Atmospheres in Hong Kong’s New Wave of Coffee Shops.” 23rd DMI: Academic Design Management Conference.

- Barber, Lachlan B. 2020. “Governing Uneven Mobilities: Walking and Hierarchized Circulation in Hong Kong.” Journal of Transport Geography 82: 102622. doi:10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2019.102622.

- BBC Travel. 22 January 2020. “The Icy Side to Hong Kong History.” BBC Travel

- Bennett, Mia M. , Lachlan B. Barber , and Benjamin L. Iaquinto . 2020. “The Campus as Battleground: Placing the University within the Hong Kong Protests.” Antipode Online. https://antipodeonline.org/2020/01/21/the-campus-as-battleground/

- Brasuell, James. 2015. “The Law in New York: Close the Door When Running Air Conditioners.” Planetizen News October 9. https://www.planetizen.com/node/81512/law-new-york-close-door-when-running-air-conditioners.

- Broadway, Michael J. , and Olivia Engelhardt . 2021. “Designing Places to Be Alone or Together: A Look at Independently Owned Minneapolis Coffeehouses.” Space and Culture 24 (2): 310–327. doi:10.1177/1206331218820244.

- Broadway, Michael J. , Robert Legg , and Teresa Bertossi . 2020. “North American Independent Coffeehouse Culture: A Comparison of Seattle with Vancouver.” GeoJournal 85 (6): 1645–1662. doi:10.1007/s10708-019-10047-9.

- Chiu, Stephen , and Tai-Lok Lui . 2009. Hong Kong: becoming a Chinese Global City . London: Routledge.

- Dowling, Robyn , and Emma Power . 2012. “Sizing Home, Doing Family in Sydney, Australia.” Housing Studies 27 (5): 605–619. doi:10.1080/02673037.2012.697552.

- Dowling, Robyn. 2008. “Accommodating Open Plan: Children, Clutter, and Containment in Suburban Houses in Sydney, Australia.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 40 (3): 536–549. doi:10.1068/a39320.

- Eco, Umberto. 1989. The Open Work . Harvard University Press.

- FACTWIRE 2020. Tiny ‘Nano Flats’ Have Proliferated in Hong Kong after Construction Rules Loosened in 2012. Hong Kong Free Press, July 21. https://hongkongfp.com/2020/07/21/tiny-nano-flats-have-proliferated-in-hong-kong-after-construction-rules-loosened-in-2012/

- Ferreira, Jennifer , Carlos Ferreira , and Elizabeth Bos . 2021. “Spaces of Consumption, Connection, and Community: Exploring the Role of the Coffee Shop in Urban Lives.” Geoforum 119: 21–29. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2020.12.024.

- Ferreira, Jennifer , and Carlos Ferreira . 2018. “Challenges and Opportunities of New Retail Horizons in Emerging Markets: The Case of a Rising Coffee Culture in China.” Business Horizons 61 (5): 783–796. doi:10.1016/j.bushor.2018.06.001.

- Frampton, Adam , Johnathan Solomon , and Clara Wong . 2012. Cities without Ground: A Hong Kong Guidebook . Oro editions. https://oroeditions.com/product/cities-without-ground.

- Gehl, Jan , and Birgitte Svarre . 2013. Jan Gehl & Birgitte Svarre. How to Study Public Life. https://tudelft.on.worldcat.org/oclc/865475474.

- Goss, Jon. 1996. “Disquiet on the Waterfront: Reflections on Nostalgia and Utopia in the Urban Archetypes of Festival Marketplaces.” Urban Geography 17 (3): 221–247. doi:10.2747/0272-3638.17.3.221.

- Habermas, Jürgen. 1991. The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society . Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Haug, A. , and M. B. Münster . 2015. “Design Variables and Constraints in Fashion Store Design Processes.” International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management 43 (9): 831–848. doi:10.1108/IJRDM-11-2013-0207.

- Kent, Anthony , and Ann Petermans . 2017. Retail Design - Theoretical Perspectives . Edited by Ann Petermans and Anthony Kent . London and New York: Routledge.

- Kim, Jungsoo , and Richard de Dear . 2013. “Workspace Satisfaction: The Privacy-Communication Trade-off in Open-Plan Offices.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 36: 18–26. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2013.06.007.

- Kotler, Philip. 1973. “Atmospherics as a Marketing Tool.” Journal of Retailing 49, (4) : 48–65.

- Lam, Janice. 2021. “Hidden Hong Kong: A History of the Cha Chaan Teng, the Humble Hong Kong Tea Restaurant.” Localiiz September 10. https://www.localiiz.com/post/food-drink-history-cha-chaan-teng-hong-kong.

- Lorne, Colin. 2020. “The Limits to Openness: Co-Working, Design and Social Innovation in the Neoliberal City.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 52 (4): 747–765. doi:10.1177/0308518X19876941.

- Lundgren, Anna , and Hans Westlund . 2017. “The Openness Buzz in the Knowledge Economy: Towards Taxonomy.” Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space 35 (6): 975–989. doi:10.1177/0263774x16671312.

- McNeill, Donald. 2014. “Airports and Territorial Restructuring: The Case of Hong Kong.” Urban Studies 51 (14): 2996–3010. doi:10.1177/0042098013514619.

- Oldenburg, Ray. 1989. The Great Good Place: Cafes, Coffee Shops, Bookstores, Bars, Hair Salons, and Other Hangouts at the Heart of a Community . 1999 ed. New York: Marlowe and Company. doi:10.4324/9780203873960.

- Piercy, Gemma Louise. 2018. “Baristas: The Artisan Precariat.” PhD Diss. , The University of Waikato, Hamilton, New Zealand.

- Roberts, Peter. 2011. “Openness as an Educational Virtue.” Geopolitics, History, and International Relations 3 (1): 9–24.

- Rose, Gillian. 2016. Visual Methodologies: An Introduction to Researching with Visual Materials . London: Sage.

- Roseberry, William. 1996. “The Rise of Yuppie Coffees and the Reimagination of Class in the United States.” American Anthropologist 98 (4): 762–775. doi:10.1525/aa.1996.98.4.02a00070.

- Shiau, Hong Chi. 2016. “Guiltless Consumption of Space as an Individualistic Pursuit: Mapping out the Leisure Self at Starbucks in Taiwan.” Leisure Studies 35 (2): 170–186. doi:10.1080/02614367.2014.982690.

- Smith, Michael D. 1996. “The Empire Filters Back: consumption, Production, and the Politics of Starbucks Coffee.” Urban Geography 17 (6): 502–525. doi:10.2747/0272-3638.17.6.502.

- South China Morning Post . 2021. “Coronavirus Shakes up Hong Kong Restaurant Scene, with New Players Opening Cafes, Veterans Chasing Lower Rents in Residential Areas.” South China Morning Post May 29, 2021. source: https://scmp.com/news/hong-kong/society/article/3135254/coronavirus-shakes-hong-kong-restaurant-scene-new-players.

- Tucker, Catherine M. 2017. Coffee Culture: Local Experiences, Global Connections . Routledge.

- Wissink, Bart , Sin Yee Koh , and Ray Forrest . 2017. “Tycoon City: Political Economy, Real Estate and the Super-Rich in Hong Kong.” In Cities and the Super-Rich , 229–252. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.