Abstract

Introduction

People with an intellectual disability (ID) are at risk of developing challenging behavior. Although previous research provided important insights into how to support people with an ID and challenging behavior, it remains unclear what various stakeholders consider to be the most essential aspects to further improve their support.

Method

Statements regarding aspects perceived necessary to improve the support to people with an ID and challenging behavior were collected in focus groups. Afterwards participants individually prioritized and clustered these statements, resulting in concept maps for people with an ID, direct support workers, and psychologists. Since only three relatives participated in the entire concept mapping procedure, no concept map could be composed based on their input.

Results

Participants generated 200 statements. In the concept map of clients, statements were mentioned regarding relational aspects, providing clarity and structure, characteristics of support staff, and professional attitude of direct support workers. Direct support workers provided statements related to their own personal competencies, the necessity of feeling supported and appreciated, and a physical safe environment. Psychologists provided statements regarding their support for direct support workers, the support for the clients, the perspective on the client, and their role as psychologists.

Conclusion

The results of this study may be a starting point to foster increased evidence based practice for the support for persons with an ID and challenging behavior. Moreover, it provides opportunities to create care founded on mutual attunement, based on listening to each other’s ideas and insight into perspectives and needs of various stakeholders.

Introduction

People with an intellectual disability are at risk of developing challenging behaviors (Emerson et al. Citation2001, Jones and Stenfert Kroese Citation2007, Sheehan et al. 2015), which may be expressed as externalizing behavior (e.g. aggression towards oneself or others), and as internalizing behavior (e.g. anxiety and depression). Prevalence rates range between 10 to 25% in people with an intellectual disability (ID) (e.g. Bowring et al. Citation2017, Emerson et al. Citation2001, Jones and Stenfert Kroese Citation2007, Sheehan et al. 2015). These behaviors may be disturbing and harmful for the person displaying the behavior, but also for their social network, such as their relatives and direct support staff (Emerson et al. Citation2001, Jones and Stenfert Kroese Citation2008, Sheehan et al. 2015).

Challenging behaviors may arise when people with an ID experience a mismatch between their personal capacities and disabilities on the one hand, and the demands and possibilities in their environment on the other hand (Bell and Espie Citation2002, Delespaul et al. 2016, Wehmeyer Citation2013). Because of the interplay between the person and its environment, challenging behaviors are seen as a socially constructed phenomenon (Stevens Citation2006). As a result, challenging behaviors can be perceived as a means of communication to control the environment and to show that the environment does not match one’s capacities (Emerson and Bromley Citation1995, Ager and O’May Citation2001, Kevan Citation2003). Intensive professional support to people with an ID displaying challenging behaviors is needed to prevent escalation and unsafe situations (Emerson et al. Citation2001). Restraints might be applied in reducing their challenging behaviors (Heyvaert et al. Citation2014). Although, restraints may cause negative emotions in both the person with an ID and the person who applies the restraint such as feelings of physical exhaustion, anxiety, and insecurity. Because of these negative emotions, various interventions for reducing these restraints have been developed (e.g. Emerson Citation2001, Feldman et al. Citation2004, Heyvaert et al. Citation2010). These interventions may focus directly on the person with an ID displaying challenging behaviors, such as applied behavior analysis, psychotherapy, cognitive behavior therapy, pharmaceutical treatment, or positive behavior support (e.g. Ager and O’May Citation2001, LaVigna and Willis Citation2012, McClean et al. Citation2005). Interventions may also focus on the environment of the person with an ID. For example on the skills of direct support workers in trying to reduce, manage, or cope with the challenging behaviors (Cox et al. Citation2015, Embregts et al. Citation2019, van Oorsouw et al. Citation2013, Stoesz et al. Citation2016, Zijlmans et al. Citation2015) or focus on the team climate (Knotter et al. Citation2016, Willems et al. Citation2016).

Recent research also identified various factors considered important in the support for people with an ID displaying challenging behaviors. Griffith et al. (Citation2013) concluded, based on a meta-synthesis of qualitative studies focusing broad on experiences in their care, that people with an ID and challenging behaviors themselves expect from direct support workers to have good interpersonal skills. In addition, based on a meta-analysis of scientific literature focusing on restrictive measures (Heyvaert et al. Citation2014), it is concluded that people with an ID express the wish to learn techniques to cope with aggressive or self-harm behaviors, and indicate the need for quiet time in their rooms and being distracted from the challenging behavior. Moreover, people with an ID and challenging behaviors indicate that proactive or protective interventions are more helpful than reactive or restrictive interventions (Griffith et al. Citation2013). Based on another meta-study of Griffith and Hastings (Citation2013) relatives of people with an ID and challenging behaviors reported to expect highly trained direct support workers to take care of their family member. In an explorative interview study, direct support workers themselves indicate that building a meaningful relationship with a client based on trust is fundamental to a good relationship and for maintaining the quality of the provided support (Hermsen et al. Citation2014).

Although previous research provided some important insights on how to support people with an ID and challenging behaviors in general, they mainly focus broadly on experiences in the care for persons with an ID and challenging behavior, but have no explicit focus on what each stakeholder group think could be relevant in improving the quality of care. It remains unclear what people with an ID themselves, their relatives, and professionals consider to be the most essential aspects to improve the support for people with an ID and challenging behaviors. Therefore, the aim of the current study is to explore the perspectives of various relevant stakeholders (i.e. people with an ID themselves, their relatives, and professionals) on how to improve the quality of care offered to this client group by applying a concept mapping method.

Materials and methods

Participants

In total, 30 participants took part in this study. They are all related to three care organizations providing support to people with an ID in the Netherlands (two organizations provided nine participants, the other provided 12 participants). Managers in the participating care organizations recruited participants via convenience sampling. The participants can be distinguished into four groups: (1) people with a mild ID or borderline intellectual functioning (IQ-score between 50 and 85) employed as experts-by-experience within their care organization (n = 9); (2) relatives of people with an ID and challenging behaviors (n = 5); (3) direct support workers (n = 7); and (4) psychologists (n = 9). All participants were aged 18 years or older and had the ability to verbally express themselves. The participating people with an ID were supported by their care organization for 9.3 years on average (range 3–16 years), with an IQ score on file ranging from 57 to 80 as provided by their organization (n = 2 missing; If information on the level of intellectual functioning of the persons with an intellectual disability was lacking, the health psychologists confirmed the intellectual disability based on their clinical judgement.). Three relatives indicated having a child with an ID and challenging behaviors, and one relative was a sibling of a person with an ID and challenging behaviors (n = 1 missing). The direct support workers and the psychologists had a working experience in the field of ID of 11.5 years and 20.1 years respectively. Additional characteristics regarding the participants are provided in .

Table 1 Characteristics participants

Procedure

After the Ethics Review Board of Tilburg University provided ethical approval (EC-2018.50), the study was conducted in cooperation with three care organizations in the Netherlands. These three organizations are part of a partnership of care organizations in long term care and share the ambition to increase the quality of care for persons with an ID and challenging behavior. Additionally, these three care organizations are members of the Academic Collaborative Center Living with an intellectual Disability (Tilburg, The Netherlands) in which science and practice collaborate closely in improving the care for persons with an ID. The authors contacted the managers responsible for knowledge development and research in these organizations to recruit people with an ID, relatives, direct support workers, and psychologists in their organization. After the managers were informed about the study, they selected potential participants who thereupon received an information letter from the researchers, explaining the aim and background of the study and informing the participants. The participants were free to stop their participation at any time, without providing a reason and without negative consequences. All participants provided written informed consent. After the concept mapping procedure (see next paragraph), all participants were invited for a joint, concluding session in which the results of the study were presented.

Concept mapping

The statements reflecting the perspective of the various stakeholders on how to improve the support of persons with an ID displaying challenging behaviors were collected, integrated, and conceptualized using the method of concept mapping. This method has been successfully applied in health care research (e.g. de Boer et al. Citation2019, van Bon-Martens et al. Citation2017), including research focusing on the care for persons with a disability (e.g. Niemeijer et al. Citation2013, Ruud et al. Citation2016). It is considered a useful method to help build evidence-based health care. Concept mapping is a computer-assisted mixed methods research design in which the integration of group processes and multivariate statistical analyses is central (Trochim and Kane Citation2005). It is a participatory approach, which consists of four consecutive stages: (1) brainstorming to gather statements; (2) prioritizing and clustering of these statements; (3) statistical analysis; and (4) interpreting the resulting concept maps.

Step 1. Brainstorming to gather statements

The aim of this first step was to gather the perspectives of the four participant groups (i.e. people with an ID, relatives, direct support workers, and psychologists) on the subject of improving the support for persons with an ID and challenging behaviors. All participants gathered at the same location. A researcher explained them the concept mapping procedure. Next, each participant group took part in a separate focus group. In these groups they provided their perspectives with regard to the following predefined focus sentence: ‘To provide better support for people with an ID and challenging behaviors, it is necessary to…’ Every focus group was supervised by two experienced ID researchers who avoided engagement in the discussion. In order to provide a psychologically safe environment, people with an ID were asked whether they preferred their direct support worker to attend their focus group for mental support. In case a direct support worker attended, they were requested not to engage in the discussion. To avoid potential biases, the focus group with direct support worker took place prior to the focus group with the people with an ID. All focus groups lasted one hour.

The focus groups were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim afterwards. Assisted by the qualitative software package Atlas.ti (Muhr Citation2005), all statements with regard to the focus sentence were coded. Duplicate statements were only coded once.

Step 2. Prioritizing and clustering statements

In the second step, the participants were individually asked to prioritize and cluster all statements derived from the focus group they attended. To complete this task, all statements of each focus group were imported into the software program Ariadne 3.0 (Severens Citation1995), resulting in four sets of statements (i.e. one set per participant group). A few days after the focus groups, the relatives, direct support workers, and psychologists received an email explaining the prioritizing and clustering task together with a personal link to perform these tasks individually on the computer. They were asked to complete these tasks within two weeks, and were invited to pose questions if needed via email or telephone. The participating people with an ID were visited by the researchers at their care organization to support them in conducting the tasks. The provided support consisted of explaining the tasks, reading the statements aloud, and providing support in working on the computer. The participating relatives and professionals were also invited at these occasions for support in conducting the tasks if needed. None of them made use of this invitation.

In conducting the tasks, participants were first asked to rate the various statements named in their focus group on a five point Likert-scale (ranging from 1 = most important to 5 = least important) in relation to the predefined focus sentence (i.e. prioritizing task). For the clients, a more convenient three point Likert-scale was chosen (ranging from 1 = most important to 3 = least important). Second, in the clustering task, the participants were asked to group all statements based on the content of each statement, that is, which they felt belong to the same topic. The Ariadne software allows for a maximum of 10 clusters to be made.

Step 3. Statistical analysis

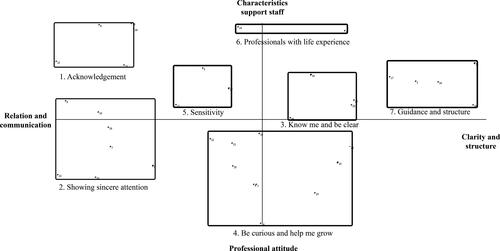

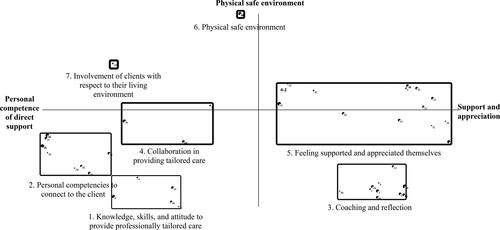

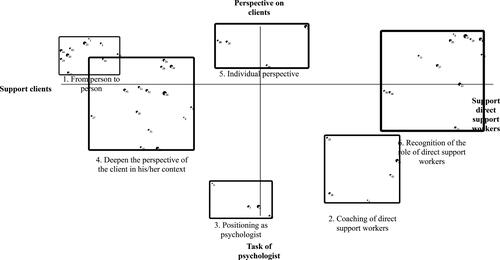

By use of Ariadne 3.0, all individually prioritized and clustered statements were combined into a group product per participant group. Statistical analysis consisted of quantitative techniques of multidimensional scaling and hierarchical cluster analysis which led to the production of visual concept maps (see ). These concept maps provide a visualization of the relatedness of the various statements and their relative importance. Based on the prioritization task, the average rating for each statement and cluster was calculated. The relative importance attached to each cluster is represented by the width of the line, which defines the cluster box. The thicker the line, the less important it was rated by the participants. Statements that are often placed in the same group during the clustering task are placed close to each other in the concept maps. In the concept map the clusters are divided over an x- and y-axis, with both ends of the axis representing a different content of clusters.

Step 4. Interpreting the concept maps

A group of five experts interpreted the four concept maps during a face-to-face group discussion based on the focus sentence: what is needed to provide better support for people with an ID and challenging behaviors? The expert group consisted of three managers responsible for knowledge development and research in their care organization (each manager was related to one of the three participating care organizations in this study), an experienced ID health-psychologist (who also participated in step 1 and step 2), and the last author (PE). During this group discussion, which was moderated by two of the researchers (SN and ET), the experts discussed the content of each cluster and entitled them. Consensus was reached for every cluster.

Results

In total, 200 statements were gathered over the four focus groups. An overview of the statements is provided in Supplementary data. The amount of statements varied from 36 to 56 for each group (clients: n = 36; relatives: n = 56; direct support workers: n = 55; psychologists: n = 53). Since five relatives participated in the focus group and only three of them completed the prioritizing and clustering tasks, no concept map could be composed based on the input of the relatives. The statements provided by relatives could therefore not be analyzed and will not be presented. provides an overview of the clusters generated by the three participant groups, together with the mean relative importance of each cluster. These clusters are based on the individual prioritization and clustering of the statements by the participants, and consequently named by the expert group.

Table 2 Clusters and their average rating for each respondent group

Concept map clients

The 36 statements provided by clients are grouped into seven clusters. These clusters are ranked in and visualized in a concept map in , with the clusters in ranked order of perceived importance (cluster 1 is perceived most important; cluster 7 received the lowest score in improving the quality of support to people with an ID and challenging behaviors). The cluster entitled ‘acknowledgment’ (cluster 1; n = 5 statements) is considered most important in improving the quality of support offered and consists of statements related to being treated equally, and direct support workers showing sincere, personal interest in getting to know the person with an ID and challenging behaviors. The second cluster ‘showing sincere attention’ (n = 7 statements) is a further operationalization of the first cluster in entailing more concrete statements such as the importance of direct support workers listening to the client instead of only reading his/her file and active listening skills. Next, the cluster ‘know me and be clear ’ (cluster 3; n = 4 statements) includes statements related to the need of direct support workers being clear in indicating when they do have time available for a client when it’s not convenient at a given time and the importance of being supported by a set group of direct support workers. In addition, it is considered important for direct support workers to be ‘curious and to help their clients grow’ (cluster 4; n = 10 statements). This cluster includes statements related to the ability of support staff to focus on the possibilities of the individual client and the provision of support to help the client further develop what he/she is capable of doing. Next, according to the clients, direct support workers should have a ‘sensitive’ attitude towards clients (cluster 5; N = 3 statements) and be ‘professionals with life experience’ (cluster 6; n = 2 statements). ‘Guidance and structure’ (cluster 7; n = 5 statements) received the lowest importance score. The clusters consists of statements related to direct support staff workers’ keeping to agreements, providing structure, and setting boundaries. As illustrated in the concept map, all clusters are grouped around an x- and y-axis (see ), with the x-axis ranging from a focus on relational aspects and communication towards the client to providing the clients with guidance and structure. The y-axis ranges from objective characteristics of direct support workers to their professional attitude.

Concept map direct support workers

Direct support workers provided 55 statements in response to the central question. These 55 statements are grouped into seven clusters (see , and ). Following the prioritization and clustering task, the cluster considered most important by direct support workers in improving the support for people with an ID and challenging behaviors is entitled ‘knowledge, skills, and attitude to provide professionally tailored care’. This cluster entails five statements related to having a basic knowledge of people with intellectual disabilities and having the ability to translate this general knowledge to the individual client. The cluster ‘personal competencies to connect to the client’ (cluster 2; n = 11 statements) describes personal competencies such as being aware of your attitude towards a client, being patient and disposing of listening skills. The cluster ‘coaching and reflection’ (n = 13 statements) is ranked 3th in order of importance and entails statements referring to the need for professional supervision, making someone responsible to motivate and coach direct support workers and the need to better prepare direct support workers to working with this particular client group. The fourth cluster ‘collaboration in providing tailored care’ consists of statements (n = 4) related to proactively collaborating with relatives of the client and allowing direct support staff to attune the support provided to create a psychologically safe environment for each individual client. Next, direct support staff consider statements related to ‘feeling supported and appreciated themselves’ as important in improving the support provided (cluster 5; n = 15 statements). Statements related to reducing their workload, being provided with the opportunity to call in additional expertise in case of incidents and feeling appreciated for their commitment and knowledge constitute this cluster. The sixth cluster (‘physical safe environment’; n = 6 statements) consists of statements concerning the physical safety in this living environment of both the clients and the direct support staff themselves, such as having housing which allows support workers to move easily in case of incidents and housing consisting of construction material suitable for people with challenging (aggressive) behaviors. The cluster ‘involvement of clients with respect to their living environment’ received the lowest score and consists of one single statement, i.e. giving people with challenging behaviors a say in the decoration of their house/room. Visualized in the concept map (), the clusters generated by the direct support workers range from their own personal competencies to the necessity of feeling supported and appreciated (x-axis). The cluster related to a physical safe environment is placed on top of the y-axis, with no direct opposite at the bottom of the y-axis.

Concept map psychologists

Six clusters were formed based on the 53 statements provided by the psychologists. According to the psychologists, the most important factor in providing better support to clients with an ID and challenging behaviors is named ‘from person to person’ and gathers statements (n = 10) focusing on the human interaction between the person with an ID and challenging behaviors and the psychologist him-/herself, such as ‘getting to know the person instead of understanding his behavior’ and ‘seeing clients as individual human beings instead of a target group’. Cluster two consists of statements (n = 5) pertaining to the ‘coaching of direct support workers’, with statements such as ‘teaching direct support workers how to empathize with the client’ and ‘simplify methodologies and make them more suitable for daily practice’. In cluster three (n = 5 statements) the ‘positioning as psychologist’ is central with example statements such as: ‘using your expertise proactively instead of reactively’ and ‘daring to take the lead in a team of professionals’. Cluster four focuses on a ‘deepen the perspective of the client in his/her context’, with statements (n = 14) such as ‘engaging more often in contact with the client’s relatives’ and combining different perspectives of what is the ‘truth’ grouped in this cluster. The following cluster is entitled ‘individual perspective’ and consists of statements (n = 5) focusing on the individual client, examples are the statements ‘offering day center activities that correspond to individual client preferences’ and ‘having an individualized and differentiated housing offer’. The cluster ‘recognition of the role of direct support workers’ (cluster 6; n = 14 statements) includes statements related to preconditions for direct support workers to provide support to people with an ID and challenging behaviors, such as providing direct support workers with sufficient time to focus on the client and having sufficient personnel. On the concept map, the x-axis ranges from how people with an ID and challenging behaviors should be supported to recognizing and supporting direct support workers in the support they provide to these clients. In addition, on the y-axis, a distinction can be made between the perspective of the clients and the perspective on their own professional role as psychologists.

Discussion

Using the concept mapping method, this study explored what people with an ID, direct support workers, and psychologists consider being the most important aspects to improve the support of people with an ID and challenging behaviors. For each participant group a concept map was composed based on their jointly generated statements, which they subsequently prioritized and clustered individually. Although the clusters are ranked from most to least important it is important to note that the clusters ranked lowest in order of importance are still considered important to the participants giving the focus sentence they reacted to during the brainstorm session (i.e. ‘To provide better support for people with an ID and challenging behaviors, it is necessary to…’). Overall, the central position of direct care workers in supporting people with an ID and challenging behaviors became apparent in all three concept maps. People with an ID themselves assigned the highest priority to clusters reflecting a high quality relationship between the client and direct support staff, i.e. clusters including feelings of acknowledgement, being treated with sincere attention and a focus on a client’s possibilities. This is in line with previous research amongst people with an ID, in which they indicate the wish to build good relationships and communicate with their direct support workers about their problems and feelings (Giesbers et al. Citation2019, Heyvaert et al. Citation2014). In addition, people with an ID highly value direct support workers’ qualities such as respect, honesty, trust, and a caring, nurturing manner (Clarkson et al. Citation2009, Griffith et al. Citation2013, Roeleveld et al. Citation2011). People with an ID also indicate that negative interactions with support staff or feeling rejected by support staff may cause challenging behaviors (van den Bogaard et al. Citation2019). This also asks for high quality interactions between client and direct support staff. Direct support also considered the relationship with the person with an ID as important, given the high prioritization they assign to the cluster entitled ‘personal competencies to connect to the client’ (cluster 2; direct support workers). Hastings (Citation2010) stressed the importance of good relationships between direct support workers and clients with an ID. Moreover, the importance of developing an interpersonal attitude towards the client with an ID and challenging behavior (Willems et al. Citation2014, Zijlmans et al. Citation2012) and focus on relational aspects of care practice (Jackson Citation2011) was underlined in previous research. However, direct support workers only mentioned one cluster pertaining to this relationship, with the other clusters consisting of statements related to conditions needed to facilitate such a high quality relationship. That is, direct support workers mention statements referring to their need for coaching and reflection (cluster 3), to feeling supported and appreciated by means of reduced workload and availability of additional expertise (cluster 5) and a physical safe working environment (cluster 6). Hastings et al. (Citation2013) described a conceptual framework to identify why challenging behaviors occur in persons with developmental disabilities. They indicated that challenging behaviors are strongly related to the context and that the behaviors of support staff are often more likely to maintain the challenging behavior instead of reducing this behavior. These behaviors of support staff are determined by their emotions, beliefs, and attitudes, which may be strongly impacted by the challenging behavior of the client. For example, in the framework is stated that support staff experience the challenging behavior as aversive and report increased levels of stress. In light of this conceptual framework, the needs regarding coaching, reflection, support and appreciation stated by the support workers can be understood. The psychologists in turn also stress the important role of direct support workers in mentioning ‘coaching of direct support workers’ (cluster 2) as essential aspects to provide high quality support of persons with an ID and challenging behaviors. Moreover, they explicitly described their own professional task in the need to position themselves as psychologist and to take the lead in a team of direct support workers (cluster 3).

The focus in the three concept maps on the relationship between the person with an ID presenting challenging behavior and support staff is in line with the concept of challenging behavior as a social construct, in which the interplay between the person and its environment is underlined (Stevens Citation2006).The concept maps of both the direct support workers and the psychologists show that they are aware of the importance of professional attitude, in addition to knowledge and skills. A professional attitude, consisting of the characteristics respect, expertise, attention, involvement, understanding, support, authenticity, empathy and warmth, is perceived fundamental for a high quality relationship (Kuis et al. Citation2010). An encouraging and facilitating learning environment is considered paramount in developing a reflective, professional attitude (Armson et al. Citation2015).

The current study identifies essential aspects to further improve the support for people with an ID and challenging behaviors, according to people with an ID themselves, direct support workers and psychologists. This is an important strength of our study, as it can be a starting point to foster increased evidence based practice for the support for persons with an ID and challenging behaviors. Moreover, it provides opportunities to create care which is based on mutual attunement, based on listening to each other ideas and insight in the various perspectives and needs. Future research should focus on how these concepts may be operationalized in practice, for example by additional in depth interviews and observations. The results of this study may also form the starting point for developing an intervention program in which the specific needs of all actors involved are taken into account.

Some limitations with regard to this study can be formulated. As the number of participating relatives was too low for the clustering and prioritizing task, a concept map could not be composed for this group. Given their important role in the lives of people with an ID and challenging behaviors, it would be recommendable for future research to include a larger group of relatives so a concept map specifically based on their perspective could be composed. Information on comorbid diagnosis or information on the adaptive functioning of the participants with an ID was lacking which hinders a comprehensive overview of the study sample. Given the small sample sizes, it was not possible to compare and contrast participants based on for example gender, age, and work experience. Although this was not the focus in our research, it could be interesting to investigate the differences in perspectives between groups in future research. Further, some participants in the group of persons with an ID needed help during the prioritizing and clustering task. Although this help should only be limited to reading out loud statements or help with the computer, some participants asked for clarification of statements or asked for approval during the tasks. In order to reduce a possible bias, no approval was provided and only clarification of words or sentences they did not understand was provided. Finally, because managers employed by the care organization selected participants, we cannot exclude the possibility this has resulted in a sample with particular characteristics. A purposeful, non-random selection of participants would contribute to the scientific rigour of future research.

In sum, based on the results of this study organizations may further improve their care for persons with an ID and challenging behaviors. Since participants provided statements in reaction to the focus sentence as to what they perceived can be improved in the support for people with an ID and challenging behaviors, one can assume that (part of) these statements are already included in the support provided by the care organizations. The outcomes of this study thus provide valuable knowledge about different perspectives on which aspects can be improved in the care for persons with an ID and challenging behaviors, which may form the basis for improvements in quality of care based on an equal dialogue and in co-creation with the various actors.

Author contributions

This study has not been published before and is not being considered for publication elsewhere. All authors contributed to the manuscript agree to the order of authors as listed on the title page. S. Nijs, E. F. Taminiau, N. Frielink and P. J. C. M. Embregts conceived and designed the study, obtained ethics approval, analyzed the data, and wrote the article in communality. S. Nijs, E. F. Taminiau and N. Frielink collected the data.

yjdd_a_1690859_sm1243.docx

Download MS Word (33.6 KB)Disclosure statement

The authors do not have any conflict of interest in publishing the results of this study.

Supplemental Data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ager, A. and O’May, F. 2001. Issues in the definition and implementation of “best practice” for staff delivery of interventions for challenging behaviour. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 26, 243–256.

- Armson, H., Elmslie, T., Roder, S. and Wakefield, J. 2015. Encouraging reflection and change in clinical practice: evolution of a tool. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, 35, 220–231.

- Bell, D. M. and Espie, C. A. 2002. A primary investigation into staff satisfaction, and staff emotions and attitudes in a unit form men with learning disabilities and serious challenging behaviours. British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 30, 19–27.

- Bowring, D. L., Totsika, V., Hastings, R. P., Toogood, S. and Griffith, G. M. 2017. Challenging behaviours in adults with an intellectual disability: a total population study and exploration of risk indices. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 56, 16–32.

- Clarkson, R., Murphy, G.H., Coldwell, J. B. and Dawson, D. L. 2009. What characteristics do service users with intellectual disability value in direct support staff within residential forensic services? Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 34, 283–289.

- Cox, A. D., Dube, C. and Temple, B. 2015. The influence of staff training on challenging behaviour in individuals with intellectual disability: a review. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities, 19, 69–82.

- de Boer, M. E., Depla, M. F., Frederiks, B. J., Negenman, A. M., Habraken, J. M., van Randeraad-van der Zee, J., Embregts, P. J. C. M. and Hertogh, C. M. 2019. Involuntary care—capturing the experience of people with dementia in nursing homes: a concept mapping study. Aging & Mental Health, 23, 498–506.

- Delespaul, P., Milo, M., Schalken, F., Boevink, W. and van Os, J. 2016. Goede GGZ! Nieuwe concepten, aangepaste taal en betere organisatie [Good mental health care! New concepts, adapted language and better organization]. Leusden, The Nederlands: Diagnosis Uitgevers.

- Embregts, P. J. C. M., Zijlmans, L. J., Gerits, L. and Bosman, A. M. 2019. Evaluating a staff training program on the interaction between staff and people with intellectual disability and challenging behaviour: an observational study. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 44, 131–138.

- Emerson, E. 2001. Challenging behavior. Analysis and intervention in people with severe intellectual disabilities. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Emerson, E. and Bromley, J. 1995. The form and function of challenging behaviours. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 39, 388–398.

- Emerson, E., Kiernan, C., Alborz, A., Reeves, D., Mason, H., Swarbrick, R., Mason, L. and Hatton, C. 2001. The prevalence of challenging behaviors: a total population study. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 22, 77–93.

- Feldman, M. A., Atkinson, L., Foti-Gervais, L. and Condillac, R. 2004. Formal versus informal interventions for challenging behaviour in persons with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 48, 60–68.

- Giesbers, S. A. H., Hendriks, A. H. C., Jahoda, A., Hastings, R. P. and Embregts, P. J. C. M. 2019. Living with support: experiences of people with mild intellectual disability. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 32, 446–456.

- Griffith, G. M. and Hastings, R. 2013. He’s hard work, but he’s worth it. The experience of caregivers of individuals with intellectual disabilities and challenging behaviour: a meta-synthesis of qualitative research. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 27, 401–419.

- Griffith, G. M., Hutchinson, L. and Hastings, R. P. 2013. “I’m not a patient, I’m a person”: the experiences of individuals with intellectual disabilities and challenging behavior—a thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 20, 469–488.

- Hastings, R. P. 2010. Support staff working in intellectual disability services: the importance of relationships and positive experiences. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 35, 207–210.

- Hastings, R. P., Allen, D., Baker, P., Gore, N. J., Hughes, J. C., McGill, P., Stephen, J. N. and Toogood, S. 2013. A conceptual framework for understanding why challenging behaviours occur in people with developmental disabilities. International Journal of Positive Behavioural Support, 3, 5–13.

- Hermsen, M. A., Embregts, P. J. C. M., Hendriks, A. H. C. and Frielink, N. 2014. The human degree of care. Professional loving care for people with a mild intellectual disability: an explorative study. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 58, 221–232.

- Heyvaert, M., Maes, B. and Onghena, P. 2010. A meta‐analysis of intervention effects on challenging behaviour among persons with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 54, 634–649.

- Heyvaert, M., Saenen, L., Maes, B. and Onghena, P. 2014. Systematic review of restraint interventions for challenging behaviour among persons with intellectual disabilities: focus on effectiveness in single-case experiments. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 27, 493–510.

- Jackson, R. 2011. Invited review: challenges of residential and community care: ‘the times they are a‐changin’. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 55, 933–944.

- Jones, P., and Stenfert Kroese, B. 2008. and Stenfert Kroese, B. Serviceusers and Staff from Secure Intellectual Disability Settings: views on Threephysical Restraint Procedures. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities, 12, 229–237.

- Jones, P. and Stenfert Kroese, B. 2007. Service users’ views of physical restraint procedures in secure settings for people with learning disabilities. British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 35, 50–54.

- Kevan, F. 2003. Challenging behaviour and communication difficulties. British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 31, 75–80.

- Knotter, M. H., Stams, G. J. J. M., Moonen, X. M. H. and Wissink, I. B. 2016. Correlates of direct care staffs’ attitudes towards aggression of persons with intellectual disabilities. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 59, 294–305.

- Kuis, E., Knoope, A. and Goossensen, A. 2010. Evaluatie van relatievorming in de laagdrempelige verslavingszorg [Quality of relationship-building in low-threshold addiction and mental health care]. Journal of Social Intervention: Theory and Practice, 19, 82–99.

- LaVigna, G. W. and Willis, T. J. 2012. The efficacy of positive behavioural support with the most challenging behaviour: the evidence and its implications. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 37, 185–195.

- McClean, B., Dench, C., Grey, I., Shanahan, S., Fitzsimons, E., Hendler, J. and Corrigan, M. 2005. Person focused training: a model for delivering positive behavioural supports to people with challenging behaviours. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 49, 340–352.

- Muhr, T. 2005. Atlas.ti: the knowledge workbench (version 5.0.66). London: Scolari/Sage.

- Niemeijer, A., Frederiks, B., Depla, M., Eefsting, J. and Hertogh, C. 2013. The place of surveillance technology in residential care for people with intellectual disabilities: Is there an ideal model of application. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 57, 201–215.

- Roeleveld, E., Embregts, P. J. C. M., Hendriks, A. H. C. and van den Bogaard, K. H. J. M. 2011. Zie mij als mens! Noodzakelijke competenties voor begeleiders volgens mensen met een verstandelijke beperking [See me as a person. Essential competencies for staff members according to people with intellectual disabilities]. Orthopedagogiek: Onderzoek en Praktijk, 50, 195–207.

- Ruud, M. P., Raanaas, R. K. and Bjelland, M. 2016. Caregivers’ perception of factors associated with a healthy diet among people with intellectual disability living in community residences: a concept mapping method. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 59, 202–210.

- Severens, P. 1995. Handbook concept mapping using Ariadne. Utrecht, The Netherlands: National Centre for Mental Health (NcGv), Talcott bv.

- Sheehan, R., Hassiotis, A., Walters, K., Osborn, D., Strydom, A. and Horsfall, L. 2015. Mental illness, challenging behaviour, and psychotropic drug prescribing in people with intellectual disability: UK population based cohort study. British Medical Journal, 351, h4326.

- Stevens, M. 2006. Moral positioning: service user experiences of challenging behaviour in learning disability services. British Journal of Social Work, 36, 955–978.

- Stoesz, B. M., Shooshtari, S., Montgomery, J., Martin, T., Heinrichs, D. J. and Douglas, J. 2016. Reduce, manage or cope: a review of strategies for training school staff to address challenging behaviours displayed by students with intellectual/developmental disabilities. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 16, 199–214.

- Trochim, W. and Kane, M. 2005. Concept mapping: an introduction to structured conceptualization in health care. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 17, 187–191.

- van Bon-Martens, M. J. H., van de Goor, I. A. M. and van Oers, H. A. M. 2017. Concept mapping as a method to enhance evidence-based public health. Evaluation and Program Planning, 60, 213–228.

- van den Bogaard, K. J. H. M., Lugtenberg, M., Nijs, S. and Embregts, P. J. C. M. 2019. Attributions of people with intellectual disabilities of their own or other clients’ challenging behavior: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Journal of Mental Health Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 1–26. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/19315864.2019.1636911.

- van Oorsouw, W. M. W. J., Embregts, P. J. C. M. and Bosman, A. M. T. 2013. Quantitative and qualitative processes of change during staff-coaching sessions: an exploratory study. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 34, 1456–1467.

- Wehmeyer, M. L. ed. 2013. The Oxford handbook of positive psychology and disability. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Willems, A. P. A. M., Embregts, P. J. C. M., Bosman, A. M. T. and Hendriks, A. H. C. 2014. The analysis of challenging relations: influences on interactive behaviour of staff towards clients with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 58, 1072–1082.

- Willems, A. P. A. M., Embregts, P. J. C. M., Hendriks, A. H. C. and Bosman, A. M. T. 2016. Towards a framework in interaction training for staff working with clients with intellectual disabilities and challenging behavior. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 60, 134–148.

- Zijlmans, L. J. M., Embregts, P. J. C. M., Bosman, A. M. T. and Willems, A. P. A. M. 2012. The relationship among attributions, emotions, and interpersonal styles of staff working with clients with intellectual disabilities and challenging behavior. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 33, 1484–1494.

- Zijlmans, L. J. M., Embregts, P. J. C. M., Gerits, L., Bosman, A. M. T. and Derksen, J. 2015. The effectiveness of staff training focused on increasing emotional intelligence and improving interaction between support staff and clients. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 59, 599–612.