Abstract

Coronavirus detrimentally impacted textile craft production and the income of indigenous artisans, including those working in the Lake Atitlán area. The article focuses on how five enterprises diversified their entrepreneurial practices and actioned strategies to support their communities during the crisis. Interviews with host textile companies based in Guatemala, the US and UK were conducted to inform case studies documenting the artisans’ experiences, the pandemic response and implications for the long-term effects on the sector. The research highlights the creative resilience of the artisans; how regional lockdowns restricting the transport of materials and provisions, led to a regional sharing economy. The crisis highlighted the advantages of home-working, belonging to co-operatives and the benefits of partnerships with NGOs for accessing essential resources, income and routes to market. Despite the loss of local income streams, engagement with and investment in digital platforms opened up new communication and sales channels, enabling artisans to maintain revenue.

Introduction

An estimated one million textile artisans are working in Guatemala (Borgen Project Citation2021), the majority of whom are women. The Lake Atitlán region in the western highlands, is home to many communities of highly skilled indigenous craftspeople specialising in weaving, dyeing and embroidery. In 2020 the global coronavirus pandemic exacerbated issues faced by people living in agrarian societies; the ongoing “fight for health rights along with their struggles for land, gender, ethnic and environmental justice” (Fischer-Mackey et al. Citation2020: 899). In addition to rural activists who seek to defend their communities (Fischer-Mackey et al. Citation2020: 900), there are a growing number of commercial and charitable social enterprises working with Guatemalan textile artisans to improve living conditions. An example of this is the Cojolya Association of Maya Women Weavers - formed in 1983 in Santiago Atitlán to support victims of the ongoing civil war (1960–1996), whose social programme is focused on supporting the “education, health, personal and professional development and economic empowerment” of Maya backstrap weavers (Cojolya Citation2022).

The lack of state welfare provision during the pandemic led to fears for how increased poverty levels would impact the health of the rural population, especially women and girls at risk of gender-based violence (UN Women Citation2022a). Having first-hand experience of the living conditions of artisans, the five textile enterprises featured in this article stepped in to “bridge the role between state and society” (Fischer-Mackey et al. Citation2020: 901) by facilitating access to materials, healthcare, education, and community services through partnerships with Non-governmental Organisations (NGOs) and donor-funded programmes. As the pandemic spread and its impact on Guatemala began to emerge it was acknowledged by the Centre for International Private Enterprise that the Orange EconomyFootnote1 would need to reimagine their practices to survive and prosper (Perez Citation2020). The reimagining process presented particular challenges for artisans and enterprises, requiring “creative solutions for getting through the crisis and preparing for the re-emergence of a post-pandemic economy” (Perez Citation2020).

The research aimed to investigate the impact of the coronavirus pandemic on artisan communities working in collaboration with five textile organizations, CojolyaFootnote2, Mercado GlobalFootnote3, MulticoloresFootnote4, A Rum FellowFootnote5 and Kakaw Designs Footnote6. The research team had established links with the first three charitable, non-profits during earlier, ethnographic research in Guatemala (2018 and 2019), and made contact with the latter, commercial social enterprises specifically for the project. The research objectives were to:

Conduct online interviews with the directors of five textile organisations to establish the impact of COVID-19 on the artisanal craft infrastructure, business design/supply chain and product development.

Document craft production and textile outcomes using film and photography, recorded in the field by the artisan organisations involved.

Develop written case studies and a short film, to convey changes to craft textile production, how they have been implemented and supported by the organisations, and how the artisans have diversified their practice.

Analyse findings to inform recommendations for sustainable models of textile practice that can support artisans beyond the pandemic.

The following sections outline the context for the study by explaining the socio-economic background of Lake Atitlán’s artisan communities, their craft textile industry and the impact of lockdowns on local movement and trade. The research methods included fieldwork undertaken by the partner organisations involving photography and video to record crafting activities, products and the artisans’ experiences of the pandemic; capturing the complexity of textile practice and products (Lehmann Citation2012), to aid understanding of processes and experiences (Piper Citation2019) and to allow the artisans to tell their own stories. The case studies provide a synopsis of the key findings, relating to the support provided and craft production strategies employed by artisans and their partnering companies.

Context

Maya Households and Lifestyles

The Lake Atitlán region, in the Guatemalan highlands, is located in the mountainous south-west of the country; with a population of 380,400 (2017 est.) the Maya – Tz’utujil, Kiche, and Kaqchikel – make up 95% of the population (Ferràns et al. Citation2018). Poverty among the indigenous community is disproportionally high. In Guatemala as a whole, where the Maya account for almost 42% population (Central Intelligence Agency Citation2022), approximately 80% of the indigenous population live in poverty (International Fund for Agricultural Development, n.d.). In the Lake Atitlán region, 72% of indigenous inhabitants live in poverty, with 32% living in absolute poverty (Ferràns et al. Citation2018).

Many Maya families live a semi-subsistence lifestyle, with extended families living on a single plot of land. The scarcity of cultivable land, the practice of land sharing, whereby a father gives his children a share of his land, and the historic confiscation of land from Maya communities, means that it is not uncommon for a family’s land to be distributed over a wide area (Asturias de Barrios Citation1997). It is estimated that the majority of Lake Atitlán’s indigenous families have less than half a hectare of land (Travieso Citation2016: 71). It is widely recognised that this provision is insufficient to meet the needs of families, with agricultural income often supplemented by textile production (Modesto and Niessen Citation2005; Modesto Citation2001; Asturias de Barrios Citation1997). For the poorest families, income from textile production is essential for survival; for others it provides “a cushion for food, medicine, religious celebrations, and a little bit of saving toward the purchase of consumer goods.” (Ehlers Citation1993: 194) while helping to alleviate the need for seasonal migration for waged agricultural work (Modesto Citation2001; Nash Citation1993). However, as Nash observes “The persistence of small plot, semi-subsistence household production supplemented by artisan production is a cultural preference that cannot be explained in economic terms alone.” (1993: 17).

Community Textile Traditions

The craft of weaving has been passed down from mother to daughter in Maya communities for generations (Hendon Citation2006; Hendrickson Citation1998; Pancake Citation1995). Community specific preparatory processes, colour combinations, patterns and motifs, and the rules that govern design (Asturias de Barrios Citation1997), alongside the fundamentals of weaving are imparted and then regulated by the community, and “therefore, are embedded in a social cultural fabric” (Chappe and Lawson Jaramillo Citation2020: 83). In a society where women are increasingly relied upon to provide monetary income for the family, as well as fulfilling domestic duties, weaving provides a practical, affordable means of generating income. The backstrap loom, being both inexpensive and portable, provides indigenous women the flexibility to weave almost anywhere at any time. Whilst women can be observed weaving on market stalls and in shops, many weave at home. This home-based textile production allows them to balance the demands of work and family life (Dickson and Littrell Citation1998), and in some communities, such as the San Ramón Community, has now extended to women producing textiles using the treadle loom – a foot loom once exclusively operated by men.

In addition to providing a livelihood and a vital source of income, weaving connects indigenous women to their ancestral past (Rosenbaum and Goldin Citation1997); textile production is “meaningful and essential work” (Berlo Citation1992: 115), an expression of personal, community and cultural identity, individual creativity and skills, as well as being central to daily life, gender roles and religious ritual. Whilst engaging in skilful and time-consuming work, creating often complex and highly decorative textiles, weaving also provides opportunities for social interaction and a “safe space for women to share knowledge” (Tohveri Citation2012: 6). The techniques, patterns and textiles of traditional Maya dress – known locally as traje – convey the weavers’ “personal, ethnic, religious and economic identities” (Tohveri Citation2012: 6). The making, wearing and adaptation of traje into saleable goods demonstrates cultural pride as well as defiance and collective solidarity in the face of oppression and marginalisation (Berlo Citation1992; Stephen Citation1991).

The significance of backstrap weaving as part of Maya cultural heritage is foregrounded by the Museo Ixchel del Traje Indígena de GuatemalaFootnote8 who engage with and promote the work of many artisans from rural communities where the craft skills are still passed on. During the pandemic, a scholarship programme, “Connecting with Your Roots” was funded by Ibermuseums for the Ixchel Museum, enabling 30 women and girls from Maya groups in Guatemala City to reconnect with their weaving arts heritage ().

Figure 1 Group of young women learning to weave on backstrap looms during the pandemic as part of the scholarship programme Connecting with Your Roots co-ordinated by Ixchel Museum, Guatemala with support of Ibermuseums.Footnote7 Photograph courtesy of Ibermuseums, Citation2021.

The Guatemalan Textile Trade

The market for Guatemalan artisan textiles is twofold – tourist and export (Moreno and Littrell Citation2001) – both are centred around Western (mainly US) consumers (Textile Infomedia Citation2023). Many artisans independently produce and sell goods via local markets, as well as being part of community co-operativesFootnote9 working in partnership with social enterprises to produce goods for sale in and outside Guatemala. The goods produced independently by artisans, often apply traditional techniques and textiles in vibrant colourways – akin to those seen in traje – to Western-style products such as scarves, bags and table linens (). The artisans work in a saturated market – market stalls and shops are filled with textiles vying for tourist attention. New styles and products are quickly copied by those keen to gain competitive advantage – devaluing the textiles and impacting production quality (Rosenbaum and Goldin Citation1997).

Figure 2 An artisan weaver in Antigua selling items made from deconstructed traje as well as newly backstrap-woven table linen. Photograph by K. Townsend, 2018.

Working in partnership with social enterprises, co-operatives can provide artisans with regular consistent work and income, with many organisations also offering community-based education, technical training and skills development. Products showcasing traditional dyeing, weaving and embroidery techniques, are designed to appeal to Western aesthetic tastes in colour, material and product application; allowing the artisans to diversify their practice without “compromising their own standards and traditions” (Blum Schevill Citation1998: 176). Meanwhile, the marketing of goods emphasises the “skill and artistry required in creating artisan products […] and the cultural contexts of production” (Rosenbaum and Goldin Citation1997: 79).

Though production for export has been criticised for mechanising and standardising artisanal work (Ibid.) in the pursuit of large-scale production “at the cost of more slowly paced systems” (Tham Citation2015: 231), under the right conditions, international trade through collaboration with responsible social enterprises, can help preserve indigenous traditions and sustain Maya cultural identity; empowering women through provision of independent income, promoting indigenous autonomy and attracting tourism (Modesto Citation2001).

Local COVID Lockdowns

Guatemala comprises of 22 departments (or districts) each led by centrally appointed governors and 332 municipalities led by autonomous local councils (OECD Citation2016). Prior to the COVID-19 outbreak, rural Guatemala already faced significant social, economic and public health challenges (Fischer-Mackey et al. Citation2020). With almost 70% of Guatemalans working in the informal unregulated economy, the country has one of the world’s highest childhood malnutrition rates (Abbott Citation2020). According to World Health Organisation and UNICEF data (Citation2020), only 44.5% of the rural population have access to drinking water services and basic sanitation provision stands at 55.5%. Although approximately half of the country’s population are internet users, less than one tenth of these (3.63%) access broadband (WorldData, c.Citation2021a), and illiteracy, language barriers and poor connectivity in Maya communities, limits use and accessibility.

All of these factors impacted the population’s ability to cope and respond when the country imposed strict nationwide lockdown measures on 21st March 2020. Varying local restrictions and curfews affected transportation, general movement obstructing the food supply chain, resulting in limited provision, price inflation and food insecurity (Ceballos et al. Citation2021). Scarcity of water and its prioritisation for drinking and cooking made handwashing and hygiene difficult. School closures and limited internet data and digital devices in Maya communities presented challenges for home-schooling, social and domestic activity. Significantly, in the Lake Atitlán region – an area whose economy relies upon tourism and agriculture (Neher et al. Citation2021) – jobs were lost and household incomes substantially reduced or diminished. The country as a whole lost 76% of its annual tourism income in 2020 (WorldData c.Citation2021b).

The appearance of white flags being flown, indicating a community’s urgent need for food and medicine, and/or women, children and the elderly in danger of violence, were reported in the media within a month of the national lockdown (Abbott Citation2020). Moreover, the aid pledged by the Guatemalan government did not appear to be reaching those most in need, with many of the country’s poor claiming that aid was not being received (Abbott Citation2020; Masek Citation2020). This left many communities reliant upon emergency aid being supplied by charities, churches and other organisations, including social enterprises working in partnership with artisans (Pretsfelder Citation2020).

Research Methods

Fieldwork

Following the publication of “Crafting the Composite Garment: The role of hand weaving in digital creation” (Piper and Townsend Citation2015), in 2017 Luciana Jabur contacted the authors, on behalf of the Museo Ixchel del Traje Indígena de Guatemala, inviting them to visit textile artisans based around Lake Atitlán, to explore opportunities for integrating alternative technologies into artisanal textile making and conservation processes. Supported by the Global Challenges Research Fund, fieldwork was undertaken in May 2018 and April 2019, where the team (the authors) connected with a number of social enterprises – including Mercado Global and Multicolores – who facilitated meetings with artisans to observe their practices. During visits to artisan communities, co-operatives, company premises, local markets and stores, and the Ixchel Museum, the researchers witnessed a vibrant craft culture, with social enterprises and highly skilled artisans working collaboratively to create contemporary products; simultaneously preserving and evolving Maya textile heritage, while appealing to Western travellers and markets.

Through the fieldwork in Guatemala and by attending the Artisan ResourceFootnote10 at the home and lifestyle trade show NY Now (February 2019 and 2020), a network of companies was established, with the aim of undertaking collaborative, ethnographic research to identify potential technical applications that could enhance the working conditions of artisans. The contacts and findings from the scoping exercise(s) were the catalyst for this study, which was specifically tailored to focus on the impact of the pandemic through remote collaboration.

Collaborators

Each of the five organisations interviewed operate within the sphere of “social enterprise,” with shared ambitions of celebrating and sustaining Maya textile traditions, alongside supporting the social welfare of their artisan groups. Working predominantly with female artisans, they aim to empower indigenous women through the provision of regular work, fair pay and access to markets.

The recruitment of project partners drew upon relationships established with companies during the fieldwork. These companies, along with other organisations, were approached to participate with the aim of representing varied business models, markets and product lines, and examining the impact of the organisational responses (to the pandemic) on the artisans’ everyday lives. A total of seven textile enterprises were contacted, five of whom accepted, for which we were very grateful, as all were in the midst of managing disruption to their operations caused by the COVID crisis.

The five participating organisations – A Rum Fellow, Cojolya, Kakaw Designs, Mercado Global and Multicolores – encompass UK, US and Guatemala based operations, working across fashion, accessories, homewares and interiors, with varying production, sales and marketing models (see ).

Table 1. Company product lines, production and sales models

Online Interviews

Due to the ongoing global uncertainty, travel restrictions and local lockdowns, along with institutional bans on international travel in UK universities, a remote collaborative approach to data collection was adopted. Using Microsoft Teams, a series of seven semi-structured interviews of up to 60-minutes were conducted with company directors and founders based in the UK, US and Guatemala, during March and April 2021 (). Guiding questions were developed (), informed by prior knowledge of the organisations’ operations and the artisans’ working practices derived from fieldwork, and by media coverage of the imposition of curfews and their impact in the region. Interviews with English speaking participants were conducted by two or more of the research team, recorded in audio-visual format and transcribed to enable qualitative analysis. Luciana Jabur carried out interviews with Spanish speakers and translated the transcript into English.

Table 2. Interviewee organisations, positions, locations and interview dates

Table 3. Guiding questions for interviews

Although the organisations had some access to artisan communities during the study period, due to an understandable reluctance to accept visitors and the health risks posed by travelling between and entering multiple communities, asking the organisations to facilitate interviews and capture bespoke film/photographic footage was deemed impracticable and an unnecessary risk.

Documentary photographs and video clips of the artisans undertaking practice and discussing their pandemic experiences were supplied by the companies; allowing the artisans’ actions and reflections to be central to each case study. A film comprising interviews and other video clips gives voice to all the participating organisations and some of the artisans (Townsend et al. Citation2021).

Case Studies

A Rum Fellow

A Rum Fellow is a London-based design studio established by Caroline Lindsell and Dylan O’Shea in 2014. Specialising in contemporary interior textiles, they create designs for the high-end interior market. Celebrating artisan craftsmanship, and employing heritage weaving and dyeing techniques, the company operate in a “very specific” (O’Shea Citation2021) exclusive market, trading predominantly with interior designers. With design taking place in the UK and production overseen by a co-ordinator in Guatemala, their textiles comprise backstrap and foot loom woven fabrics, predominantly made to order and sold by the metre. They are “uncompromising” in their approach, prioritising high quality at all stages of their operation “to produce the best fabrics we can” (O’Shea Citation2021).

Working with two backstrap weaving groups and four family-run weaving workshops, A Rum Fellow work with their artisans on a fair trade, “fair exchange basis” (O’Shea Citation2021) – empowering them through meaningful work, skill development and income. In-line with Guatemalan weaving traditions, the female backstrap weavers work at home, aligning their weaving with their domestic duties, whilst workshop-based foot loom production is predominantly undertaken by men.

The COVID-19 outbreak coincided with the company’s US launch in collaboration with SchumacherFootnote11, a high-end interior textile company. In contrast to A Rum Fellow’s make-to-order model, Schumacher operate a stock holding system. This approach and their on-going contract, along with pre-pandemic investment in yarn stock, provided a level of security and stability as the pandemic hit, as O’Shea recalls:

[…] we spent a lot of the previous year, in 2019, doing travelling and training work, you know, capacity building with all of our workshops. And so, when COVID hit we were actually in quite a strong position […]

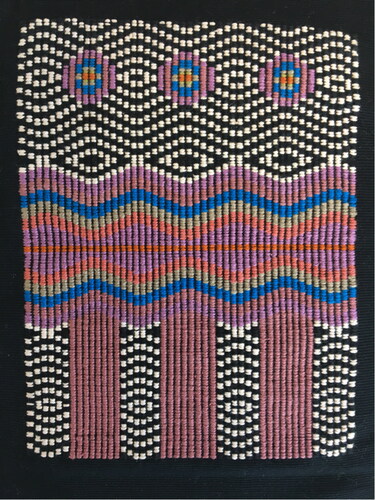

Figure 3 Backstrap woven ‘artwork’ devised by A Rum Fellow as a new product line and revenue stream for the artisans during the pandemic. Photograph by K. Townsend, Citation2021.

A Rum Fellow’s partnership with Schumacher, the changes in their production and supply model, and materials and training investment, left them well positioned to withstand the impact of the pandemic. The company’s unique market position, prioritising of quality and well-established relationships with their artisan communities contributed to their resilience. Travel restrictions necessitated the streamlining of communication, with the creative, expanded use of technology. This included the social media platform WhatsApp, facilitating direct contact between the Guatemala-based weavers and the London studio, which, long-term has the potential to reduce the need for long-haul travel and its associated impacts.

According to O’Shea (Citation2021), a focus on quality over volume, could be transferrable and beneficial to the artisan sector as a whole; A Rum Fellow have demonstrated that valuing artisan craftsmanship, in combination with contemporary design and “sensitivity to the global market” (Ibid.) represents a successful business model that can positively impact artisan communities.

Cojolya Association of Maya Women Weavers

Cojolya is a registered non-profit organisation founded in 1983 during the Guatemalan civil war to support widows who lost their husbands due to the military persecution. Its mission is to preserve backstrap weaving and make it a financially viable craft for indigenous women by providing market access, social development and a commitment to a fair living wage.

[…] artisans receive wages that are more than double what an average weaver would make on local markets. (Cojolya Citation2018)

Supplied with design guidelines and locally sourced yarns, the artisans work from home producing contemporary textiles employing BrocadeFootnote12 and JaspéFootnote13 weaving, and hand embroidery – techniques featured in local traje.

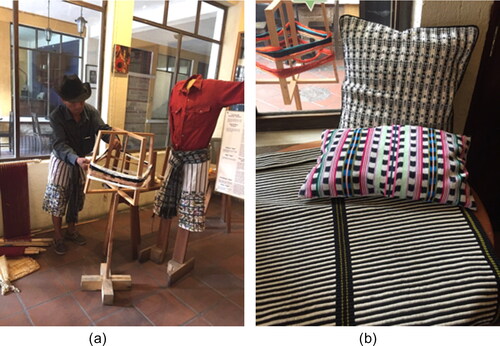

Interior and fashion accessories are sold in Cojoyla’s Santiago Atitlán store, via their online shop, and by a small number of national and international retailers, whilst the Cojolya museum, tours and weaving classes educate tourists about ethical craft production ( and ). The provision of professional development training supports the diversification of craft skills amongst the artisans, and workshops educate them on gender equality and work rights. Cojolya’s children’s education initiatives strive to address financial, social and academic factors that contribute to high school dropout rates in indigenous communities.

Figure 4 a & b. Images of Cojolya’s store and museum in Santiago Atitlán, including an image of an artisan preparing a warp and woven products. Photographs by K. Townsend, 2018.

Initially, facilitated by remote working arrangements, the artisans were able to continue work, but as the pandemic unfolded tourism ceased and sales and orders diminished. Nevertheless, Cojolya kept their artisans weaving and making masks at their own expense, although some non-artisan staff had to be laid-off. Executive Director, Carina Coché Vásquez (Citation2021), explained the business impact:

The blow was so hard for everybody and our American and European clients were the first to feel COVID’s economic fallout […] We no longer had either direct sales [through the store] or new orders coming in. Literally, zero sales.

Cojolya’s tourism focused business model proved restrictive during the pandemic – leaving them vulnerable and raising critical questions about the future direction of the business. The introduction of new product ranges was considered too risky. Instead, social media was used as a platform for artisans to sell work that they would have ordinarily sold to tourists. These online platforms now provide a vital connection to the international market for product sales, to promote the artisans, the organisation and to raise the funds on which Cojolya depends. Going forward, innovative approaches to utilising “digital spaces” will be necessary to adapt to the new normal (Perez Citation2020). This will include modifications to product lines to appeal to the national market – the Guatemalans themselves – consumers that “don’t usually buy crafts” (Coché Vásquez Citation2021).

Kakaw Designs

Set-up in 2013 as a social enterprise by Guatemalan born Mari Gray, Kakaw Designs recognise the skilfulness and craftsmanship of their artisans – they represent skill and hard work, with an emphasis on talent, value and quality rather than charity, for the meaningful long-term development of Guatemala. With a focus on sustaining artisan textile traditions by producing high-quality, ethically and sustainably produced textile goods, Kakaw Designs support artisan creativity and innovation, provide fair pay, and raise awareness and appreciation of handmade goods.

The company offers a range of fashion and interior products and a small-batch design service, along with “experiences” including textile tours, dyeing, weaving and embroidery classes. Sold through stores in Antigua, to a small number of wholesale clients, and via their online shop, the products feature naturally dyed handwoven textiles, with decorative finishing and leatherwork. Developed in collaboration with artisan groups and individual craftspeople, the textiles draw upon the traditional techniques of traje. Kakaw Designs value the uniqueness of the artefacts, nurturing and promoting “one-of-a-kind variations,” as Gray (Citation2021) describes:

[…] we just send them the threads and say send me what you can, make what you can and send it to me. I will sell it in certain general specifications, and we just dedicate more time and energy into representing those [unique] pieces.

The company’s existing scale, online presence and focus on retail sales, enabled the trialling of ideas during the pandemic. Augmented by Artisan Direct, the cancellation of orders was offset by increased online sales. The provision of online weaving classes (), along with Artisan Direct, attracted new audiences, including other crafters and artists, and those wanting to support the artisans. Although Gray (Citation2021) has reservations about the artisans being perceived as in need of “charity,” she recognises the tangible connections forged between artisan and consumer through the purchase of traditional Maya designs:

Figure 5 Online artisan-led weaving workshop staged by Kakaw Designs during the global pandemic. Photograph courtesy of Kakaw Designs, Citation2021.

Their [consumers] main goal might be to support the artisans and I just happen to be the mediator. It’s more socially driven […] products I had nothing to do with, they prefer to buy because I think the benefit is a little bit more obvious somehow.

Enabling the artisans to tell their own stories, by facilitating the making and selling of bespoke textile objects informed by personal interpretations of their cultural heritage, demonstrates an important shift in the established model of designer-led production. The implicit approach whereby the artisan is respected as a creative in their own right and as a partner in jointly devised outcomes, points towards a much-needed “collaboration methodology through which designer/founders can frame their future work” (Chappe and Lawson Jaramillo Citation2020: 80). Kakaw’s model represents sustainable development in the artisan sector, whereby skill and talent, rather than neediness and charity, are the core marketing strategies.

Mercado Global

Mercado Global, a social enterprise with offices in Brooklyn, United States and Panajachel, Guatemala, work with almost 1000 female artisans; empowering them to establish community businesses to sustain their heritage weaving techniques and support themselves financially. Using a combination of backstrap and treadle looms, textile production takes place in the community, with fabrics transformed into contemporary fashion accessories () for US export. The products apply traditional weaving, hand embroidery and embellishment, and dyeing techniques. Through partnerships with brands including Levi’s, Anthropology and Nordstrom, Mercado Global and their artisans demonstrate the viability of socially responsible fair-trade sourcing and production for the mainstream retail market.

Figure 6 Masks made from Mercado Global’s stock fabric. Photograph by K. Townsend, Citation2021.

Working with local artisan co-operatives, the organisation delivers training and an asset development programme, focusing on financial literacy, business management, self-esteem and mental health – encouraging saving and incentivising the purchase of looms and sewing machines, enabling the women to establish their own businesses. To date, 25% of artisans have launched and maintained independent businesses, alongside their work for Mercado Global.

As orders for bags and fashion accessories declined early in the pandemic, the company quickly pivoted to producing medical and non-medical grade face coverings – securing orders with US hospitals and organisations. The artisans became essential workers – sewing for the “Masks Where They’re Needed Most” and “Buy One, Give One” () campaigns (Borgen Project Citation2021) – with many becoming the sole income provider in their household.

As an international enterprise, Mercado Global was well positioned for working digitally and they quickly implemented online mask-making tutorials and distributed educational materials about COVID-19. Despite some artisans having no access to smartphones, relationships with local artisan co-operatives facilitated the sharing and translation of information. The co-operatives also provided a framework through which to organise aid, identify community needs and restructure the operational system to deliver raw materials, as well as cutting, packaging and transportation to facilitate production. The company’s strategy highlighted “the importance of networks in creating collective effort” (Perez Citation2020) and resulted in Mercado Global recording the highest sales in their history.

Alongside increased demand for sustainably produced authentic goods, the company also recognise a potential, positive long-term legacy of the pandemic – it has enabled the opportunity to rethink gender roles in a country that has one of the highest inequality indexes in the world. Director of Operations in Guatemala, Lidia Garcia (Citation2021), observes:

I think this is beautiful; that is, this example of the children of the artisans who are seeing that women also have an important role or they occupy the same position as men in the family. I think it is very important to pass that on to the children, both boys and girls.

Multicolores

Multicolores is a non-profit organisation working with Maya Kiche, Kaqchiquel and Tz’utujil women across nine communities. The organisation specialises in embroidery and rug-hooking – a non-traditional technique in which the artists are trained and which has transformed many of their lives (Wise and Conway-Daly Citation2018). They produce unique art-pieces, rugs, cushion covers and story cloths, that draw upon traditional Maya woven motifs and dress. Whilst design is overseen by the company’s Creative Director, the artistsFootnote15 retain creative agency over their work; resulting in distinct products that set them apart from other textile enterprises. Operating a predominantly face-to-face business model whereby community, partnership and storytelling are central, products are sold through the Multicolores gallery in Panajachel and tradeshows such as the International Folk Art Market (IFAM) Santa Fe in the US. The company also offer rug-hooking and textile tours in the artists’ communities.

As is the norm in the artisan sector, payment is on a piece work basis. Working from home the artists “have the freedom to produce as much as they want in a given month” (Krieder Carlson Citation2021) and are paid immediately when finished pieces are received by Multicolores. Working closely with their artists, they foster long-term collaborative relationships, as Development Director Cheryl Conway-Daly (Citation2021) explains:

We have very deep and very long-lasting relationships with the artists that we work with […] They are part of Multicolores, it is as much about them as it is about us.

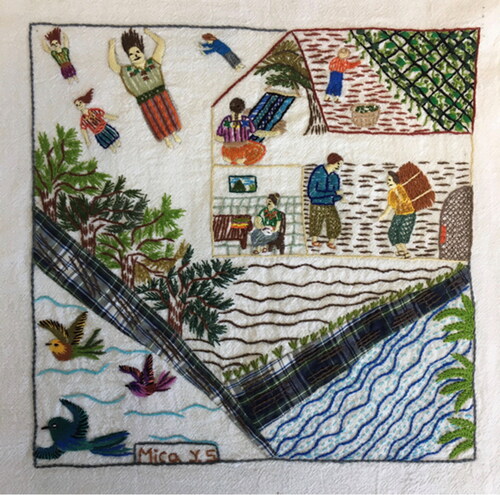

Additionally, the organisation implemented strategies to support the health and wellbeing of their artists, their families and communities, focusing on communication, resource provision and COVID prevention. In partnership with the Association for Health and Development Guatemala, COVID education, prevention and food kits were delivered monthly. The artists were also encouraged to draw upon their experiences of the pandemic to influence their designs, with briefs set to “encourage creative growth.” such as reflecting on “a day in my life during COVID” (Conway-Daly Citation2021) which resulted in some very emotive story cloths, as illustrated in . An exhibition entitled “Story Cloth,” disseminated stories and outcomes by artisans working through COVID (Townsend et al. Citation2022).

Figure 7 Story Cloth entitled ‘My Life During the Quarantine’ designed and hand-embroidered by Micaela Yaj Sunú, Santiago Atitlán, for Multicolores Guatemala. Photograph by K. Townsend Citation2022.

Although face-to-face sales were impacted and limited access to the internet and digital technologies presented challenges, the resourcefulness and ingenuity of the artists and their close relationship with the organisation contributed to a successful transition to e-commerce. In combination with a focus on storytelling, the digital transition has facilitated new ways of connecting with existing and potential customers, donors and supporters; providing a “cultural exchange experience” (Krieder Carlson Citation2021) and enabling diversification of sales for the long-term sustainability of the business.

Discussion

The existing structural, social and economic inequalities in Guatemala intensified the impact of the pandemic in the country’s rural artisan communities. Longstanding utilities, transport, technological and medical issues, along with a lack of state welfare provision, mistrust of government and authorities within Maya communities, and limited government capacity to respond to COVID-19, left churches, charities, NGOs and social enterprises plugging the gap and becoming facilitators of healthcare, education and community services (Abbott Citation2020; Fischer-Mackey et al. Citation2020). The organisations we interviewed felt the pressure to find solutions to not only keep their businesses going, but also to support the artisans, their families and wider communities in meeting their basic needs by providing a source of income, food and hygiene supplies and COVID prevention education.

Although all of the companies were able to provide a level of financial security to their artisans, it is evident that those with more varied sales models – e-commerce and face-to-face, national and international trade and retail – had greater capacity to adapt and diversify to maintain production and sales. Kakaw Designs and Multicolores were able to pivot to focus on online sales and engagement by expanding their existing provision. A Rum Fellow and Mercado Global’s relationships with US brands and external organisations and the introduction of new product lines alleviated the impact of a reduction in demand for their mainline products. However, Cojolya’s reliance upon the tourist market left them supporting their artisans at their own expense, supplemented by fund raising, when their orders and sales diminished.

Company resilience, and the ability to adapt and innovate in the face of significant disruption can, in part, be attributed to longstanding relationships with and investment in the artisans and their communities. Investing in technical skills and professional development training paved the way for the organisations to maintain and manage production from a distance, when in-person interaction and travel became unviable. Financial literacy training meant that some artisans were initially able to withstand the impact of price rises and loss of household income. And whilst the onset of the pandemic prompted workers worldwide to adopt home-based working for the first time, the artisans, who have been working from home for centuries, were equipped and able to continue to craft textiles. Inevitably, pandemic restrictions and lockdowns presented them with new challenges, not least home schooling their children with limited digital technology and access to the internet.

The pre-pandemic community investment afforded the companies – in partnership with their artisans – the capacity to not only react and respond to the pandemic, but to harness the opportunity; demonstrating resilience by modifying their working practices and transforming their communication by embracing “digital spaces” and “recombining sources of experience and knowledge” (Folke et al. Citation2010). Facilitated by lean business structures and simple supply chains, the organisations had the flexibility to make quick decisions; helping them to adapt their business models under the daunting reality of supply chain disruption, budgetary challenges and product innovation constraints. The ability of the organisations to adapt and take risks – marketing and sale of artisan goods (Kakaw Designs), delivering online events and workshops (Kakaw Designs and Multicolores), shifting to the wholesale production of masks (Mercado Global) – is testament to the foundation of trust between them and their artisans “facilitating different transformative experiments at small scales and allowing cross-learning and new initiatives to emerge” (Ibid.). The taking of risks resulted in the organisations, not only maintaining, but augmenting their income.

Conclusions and Further Work

When first invited by the Ixchel Museum in 2017 to scope the potential for integrating digital technology into hand weaving practices, we envisaged possibilities for seeking funding to purchase and train young people to use electronic weaving tools. Having forged partnerships with the featured organisations, and others involved in textile arts and social innovation projects, we have come to a very different conclusion about what might benefit the artisan textile sector. Essentially, the most useful form of digital technology is not dedicated hardware and software applications, but ubiquitous social media platforms, that are accessible and familiar, at least as a starting point.

All five organisations have leveraged mobile technologies and communication platforms, in particular mobile phones and tablets, WhatsApp and Zoom. By enhancing the “communication paths” (Tham Citation2015: 230) between the artisans, organisations and consumers, these digital technologies and platforms have allowed the companies to draw upon their expertise in storytelling to attract new audiences and strengthen bonds with existing clientele. Prior to the pandemic, the companies employed social media and their company websites to share the stories of their enterprises, artisans and the work they produce; embedding their textiles with meaning, value and authenticity, through an emphasis on skilfulness, craftsmanship and creativity of the artisans, alongside the preservation of indigenous traditions. Cojoyla, Kakaw Designs and Multicolores’ tourist-focused model, encompassing physical, in-person tours and workshops, gives the artisans a voice; breaking down the “remoteness” and “invisibility” (Tham Citation2015: 230) of textile production to provide transparency and facilitate emotional connection. The artisans tell their own story, share their knowledge, expertise and lived experience. Shifting these activities online, along with the sale of independently produced artisan goods, will continue to extend their reach beyond the boundaries of Lake Atitlán, Guatemala and the tourist market.

Despite low literacy levels among artisans, language barriers and connectivity issues, the organisations have harnessed digital technologies to “maintain open and fast communication channels with artisan groups” (Chappe and Lawson Jaramillo Citation2020: 81). Facilitated by artisan group leaders who took on the responsibility of translating and disseminating information and drawing on the resourcefulness and adaptability of the artisans, education, training and production continued, alongside new product developments. Although this increased use of technology was enforced by COVID-19, it has resulted in the upskilling of both the artisans and the organisations who have evolved their business models and practices, opening up new opportunities for future innovation, the long-term sustainability of their operations and significantly, Guatemala’s cultural heritage and its artisan textile sector.

In response to the predicted shift to be online to survive (Perez Citation2020) this collaborative project will continue by the authors seeking further research funding to support four of the groups’ artisans to enhance their digital literacy skills. The methodology will build on the initiative introduced by Multicolores in 2020, by providing hardware such as tablets (or PCs) and training in digital photography, video and editing to record craft textile practices and outcomes professionally. Funding could also be directed to the purchasing of, and training in product cataloguing and marketing software, website design and digital ethics.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank our interviewees: Carine Coché Vásquez, Cheryl Conway-Daley, Dylan O’Shea, Lidia Garcia, Maddy Krieder Carlson, Mari Gray and Ruth Alvarez-DeGolia; participating organisations and their artisans: A Rum Fellow, Cojolya, Kakaw Designs, Mercado Global and Multicolores; and the Ixchel Museum of Indigenous Textiles and Clothing. With special thanks to Tim Bassford, Creative Director of Turbine Creative, for editing the film that accompanies this research.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Anna Piper

Anna Piper is a textile designer and Senior Lecturer in Fashion Management and Communication at Sheffield Hallam University (UK). Anna recently completed her practice-led PhD Material Relationships: The textile and the garment, the maker and the machine (2019), a Nottingham Trent University Vice Chancellor Funded Studentship, investigating 3D/composite garment and pattern weaving integrating hand and digital jacquard technologies. Her research interests include zero-waste design, social and sustainable textile innovation, embodied knowledge and digital craft. [email protected]

Katherine Townsend

Katherine Townsend is Professor of Fashion and Textile Practice at Nottingham Trent University where she leads the Digital Craft and Embodied Knowledge group in the Centre for Fashion and Textile Research. Katherine’s research encompasses sustainable fashion and textile design, cultural heritage and social innovation. Current projects focus on the impact of the pandemic on Guatemalan textile artisans, supported by the Global Challenges Research Fund and “Redesigning Reusable PPE Gowns” in response healthcare workers experiences of treating patients with COVID-19 (AHRC). She is co-editor of the journal of Craft Research (Intellect) and lead editor of Crafting Anatomies: Archives, Dialogues, Fabrications (Bloomsbury, 2020).

Luciana Jabur

Luciana Jabur is a US-based independent researcher. Born and raised in Brazil, Luciana studied for her MA in Marketing and Communication at the University of Arts London (UK), and has lived and worked in multiple South and Central American countries, including Guatemala. She worked as an affiliated researcher of the Development Through Empowerment, Entrepreneurship, and Design Lab for the Artisan Sector, led by Parsons School of Design (US). She started (Hand)Made to Market, a platform that aims to grow as a directory of sources and links to other artisan-related research, websites, NGOs, contributing to publishing the efforts of the artisan sector as a whole. Luciana currently serves on the Board of Directors of Friends of the Ixchel Museum.

Notes

1 The Orange Economy is another term for the Creative Economy, “whose main purpose is the production or reproduction, promotion, dissemination and/or the marketing of goods, services and activities that have cultural, artistic or patrimonial content” (UNESCO cited in “Orange Economy: The preservation of cultural industries in Columbia”, 2019).

8 Translated as: Ixchel Museum of Indigenous Textiles and Clothing (Museo Ixchel del Traje Indígena, Citation2023)

9 The co-operative model emerged in the early 1980s to assist women who had lost their husbands, homes and families in the civil war. Supported by government, non-government and alternative trading organisations, the co-operative system sought to produce marketable products through the adaptation and application of traditional skills. (Blum Schevill, Citation1998).

10 The Artisan Resource at NY Now features “handmade products by global artisans and cooperatives that demonstrate a commitment to design innovation, cultural preservation and sustainability.” (NY Now, Citation2023).

12 The brocade technique involves the inlaying of supplementary weft yarns to create decorative patterns.

13 Jaspé is a form of Ikat weaving, where patterns are created by resist dyeing the warp and or/weft yarns prior to weaving.

14 See the UN Women Guatemala Program (Citation2022b).

15 Multicolores refer to their artisans as artists, reflecting their emphasis on creative agency and the freedom of the artists to express themselves and their textile traditions through their designs (Conway-Daly, Citation2021).

References

- Abbott, J. 2020, May 22. “Guatemala’s White Flags Indicate Pandemic’s Deadly Side-Effect: Hunger.” The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2020/may/22/guatemala-white-flags-hunger-coronavirus

- Asturias de Barrios, L. 1997. “Weaving and Daily Life.” In J. J. Foxx and M. Blum Schevill (eds.), The Maya Textile Tradition, pp. 56–128. London: Harry N. Abrams Inc. Publishers.

- Berlo, J.C. 1992. “Beyond Bricolage: Woman and aesthetic strategies in Latin American textiles,” Res: Anthropology and Aesthetics, 22: 115–134. https://www.jstor.org/stable/i20166848

- Blum Schevill, M. 1998. Dolls and Upholstery: The commodification of Maya textiles of Guatemala. In Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. Vol. 203, pp. 175–183. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/203/

- Borgen Project. 2021, April. “Poverty, COVID-19 and Slow Fashion.” Borgen Magazine. https://www.borgenmagazine.com/slow-fashion-in-guatemala/

- Ceballos, F., Hernandez, M.A. and Paz, C. 2021. “Short-Term Impacts of COVID-19 on Food Security and Nutrition in Rural Guatemala: Phone-Based Farm Household Evidence Survey,” Agricultural Economics (Amsterdam, Netherlands), 52(3): 477–484. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/agec.12629

- Central Intelligence Agency. 2022, March 23. “Explore All Countries: Guatemala.” The World Factbook. Retrieved October, 15, 2022, from https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/guatemala/

- Chappe, R. and Lawson Jaramillo, C. 2020. “Artisans and Designers: Seeking Fairness with Capitalism and the Gig Economy,” Dearq, 1(26): 80–87.

- Coché Vásquez, C. 2021, March 10. Executive Director, Cojoyla: Interview with Luciana Jabur. Online.

- Cojolya. 2018. Annual Report 2017-2018. ISSUU. https://issuu.com/cojolya/docs/annualreport2017issuu

- Cojolya. 2022. Social Impact. https://cojolya.org.gt/nuestra-historia/

- Conway-Daly, C. 2021, March 21. Development Director, Multicolores: Interview with Katherine Townsend and Luciana Jabur. Online.

- Dickson, M.A. and Littrell, M.A. 1998. “Organisational Culture for Small Textile and Apparel Businesses in Guatemala,” Clothing and Textiles Research Journal, 16(2): 68–78.

- Ehlers, T. 1993. “Belts, Business and Bloomingdales: An Alternative Model for Guatemalan Artisan Development.” In J. Nash (Ed.) Crafts in the World Market: The Impact of Global Exchange on Middle American Artisans, pp. 181–196. Albany: State University of New York Press.

- Ferràns, L., Caucci, S., Cifuentes, J., Avellán, C., Dornack, C. and Hettiarachchi, H. 2018. “Wastewater Management in the Basin of Lake Atitlan: A Background Study,” UNU-FLORES Working Paper Series 6. https://collections.unu.edu/view/UNU:645

- Fischer-Mackey, J., Batzin, B., Culum, P. and Fox, J. 2020. “Rural Public Health Systems and Accountability Politics: Insights from Grassroots Health Rights Defenders in Guatemala,” The Journal of Peasant Studies, 47(5): 899–926.

- Folke, C., Carpenter, S.R., Walker, B., Scheffer, M., Chaplin, T. and Rockström, J. 2010. “Resilience Thinking: Integrating Resilience, Adaptability and Transformability,” Ecology and Society, 15(4): 20. http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol15/iss4/art20/

- Garcia, L. 2021, April 26. Director of Operations, Mercado Global: Interview with Luciana Jabur. Online.

- Gray, M. 2021, April 9. Founder, Kakaw Designs: Interview with Anna Piper and Luciana Jabur. Online.

- Hendon, J.A. 2006. “Textile Production as Craft in Mesoamerica: Time, Labor and Knowledge,” Journal of Social Archaeology, 6(3): 354–378.

- Hendrickson, C. 1998. Weaving Identities: Construction of Dress and Self in a Highland Guatemalan Town. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Ibermuseums. 2021. Group of Young Women Learning to Weave on Backstrap Looms during the Pandemic as Part of the Scholarship Programme Connecting with Your Roots Co-ordinated by Ixchel Museum Guatemala with Support of Ibermuseums [Photograph]. Ibermuseums, Lisbon, Portugal.

- International Fund for Agricultural Development. n.d. Guatemala. https://www.ifad.org/en/web/operations/w/country/guatemala

- Kakaw Designs. 2021. Online Artisan-Led Weaving Workshop Staged by Kakaw Designs during the Global Pandemic [Photograph]. Kakaw Designs, Antigua, Guatemala. https://kakawdesigns.com/collections/online-classes

- Krieder Carlson, M. 2021, March 11. Creative Director, Multicolores: Interview with Katherine Townsend and Luciana Jabur. Online.

- Lehmann, S.A. 2012. “Showing Making: On Visual Documentation and Creative Practice,” The Journal of Modern Craft, 5(1): 9–23.

- Masek, V. 2020, May 07. “White Flags as Guatemalans Grow Hungry,” Latin America News Despatch. https://latindispatch.com/2020/05/07/white-flags-as-guatemalans-grow-hungry/

- Modesto, H.S. 2001. The Socio-economic Impact of Weaving and Naturally Dyed Textile Production in San Juan La Laguna, Guatemala [Master’s thesis, University of Alberta]. Education Research Archive. https://era.library.ualberta.ca/items/ee8baf91-4463-45d0-a883-22f63cb87871

- Modesto, H.S. and Niessen, S. 2005. “Revival of Traditional Practices as a Response to Outsiders’ Demands: The Resurgence of Natural Dye Use in San Juan La Laguna, Guatemala,” Ethnobotany Research and Applications, 3(2005): 155–166. https://ethnobotanyjournal.org/index.php/era/article/view/66

- Moreno, J. and Littrell, M.A. 2001. “Negotiating Tradition: Tourism Retailers in Guatemala,” Annals of Tourism Research, 28(3): 658–685.

- Museo Ixchel del Traje Indígena. 2023. The Museum. https://museoixchel.org/museum/

- Nash, J. 1993. “Introduction: Traditional Arts and Changing Markets in Middle America.” In J. Nash (ed.) Crafts in the World Market: The Impact of Global Exchange on Middle American Artisans, pp. 1–22. Albany: State University of New York Press.

- Neher, T.P., Soupir, M.L. and Kanwar, R.S. 2021. “Lake Atitlan: A Review of Food, Energy and Water Sustainability in Guatemala,” Sustainability, 13(2): 515.

- NY Now. 2023. Artisan Resource. https://nynow.com/handmade/artisan-resource

- O’Shea, D. 2021, March 24. Co-founder, A Rum Fellow: Interview with Katherine Townsend and Luciana Jabur. Online

- OECD. 2016. “Guatemala Unitary Country Profile.” https://www.oecd.org/regional/regional-policy/profile-Guatemala.pdf

- OECD/ILO. 2019. Tackling Vulnerability in the Informal Economy, Development Centre Studies. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- Orange Economy: The preservation of cultural industries in Colombia [Editorial]. 2019, March 17. Latin American Post. https://latinamericanpost.com/26787-orange-economy-the-preservation-of-cultural-industries-in-colombia

- Pancake, C. 1995. “Communicative Imagery in Guatemalan Indian Dress.” In M. Blum Schevill, J. C. Berlo, and E. B. Dwyer (eds.) Textile Traditions of Mesoamerica and the Andes: An Anthology, pp. 42–62. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Perez, F. 2020, July 7. “Guatemala’s Orange Economy Amid COVID-19: Reimagination for the Creative Sector,” CIPE Blog. https://www.cipe.org/blog/2020/07/23/guatemalas-orange-economy-amid-covid-19-reimagination-for-the-creative-sector/

- Piper, A. 2019. Material Relationships: The Textile and the Garment, the Maker and the Machine. [Doctoral dissertation, Nottingham Trent University]. IRep. https://irep.ntu.ac.uk/id/eprint/39927/

- Piper, A. and Townsend, K. 2015. “Crafting the Composite Garment: The role of hand weaving in digital creation,” Journal of Textile Design Research and Practice, 3(1-2): 3–26.

- Pretsfelder, J. 2020, July 17. “9 Guatemalan Artisan Initiatives to Follow & Support Right Now.” Remezcla. https://remezcla.com/lists/culture/9-guatemalan-artisan-initiatives-to-follow-support-right-now/

- Rosenbaum, B. and Goldin, L. 1997. “New Exchange Processes in the International Market: The Re-making of Maya Artisan Production in Guatemala,” Museum Anthropology, 21(2): 72–82.

- Stephen, L. 1991. “Culture as a Resource: Four Case Studies of Self-Managed Indigenous Craft Production in Latin America,” Economic Development and Cultural Change, 40(1): 101–130.

- Textile Infomedia. 2023. “Textile Industry in Guatemala: Guatemala Textile Apparel Business Overviews.” https://www.textileinfomedia.com/textile-industry-in-guatemala#Top10GuatemalaTextileExporter

- Tham, M. 2015. “Creative Resilience Thinking in Textiles and Fashion,” In J. Jeffries, C. D. Wood and H. Clarke (eds.) The Handbook of Textile Culture, pp. 225–240. London: Bloomsbury.

- Tohveri, P. 2012. Weaving with the Maya: Innovation and Tradition in Guatemala. CreatesSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

- Townsend, K., Piper, A. and Jabur, L. 2021. Crafting Textiles Through COVID: Stories from Guatemala [Documentary Film]. Vimeo. https://vimeo.com/651821145/015605f5a6

- Townsend, K., Piper, A. and Jabur, L. 2022. Bonington Vitrines #18: Story Cloth [Exhibition]. Bonington Gallery, Nottingham. https://www.boningtongallery.co.uk/event/story-cloth/

- Travieso, E. 2016. “Lake Atitlán, Guatemala: The possibility of a shared world,” Alternautas, 3(2): 70–80.

- UN Women. 2022a. “Gender-Based Violence: Women and Girls at Risk.” https://www.unwomen.org/en/hq-complex-page/covid-19-rebuilding-for-resilience/gender-based-violence

- UN Women. 2022b. “Americas and the Caribbean: Guatemala.” https://lac.unwomen.org/en/donde-estamos/guatemala

- Wise, M.A. and Conway-Daly, C. 2018. Rug Money: How a Group of Maya Women Changed Their Lives through Art and Innovation. Chicago: Thrums Books.

- World Health Organisation and UNICEF. 2020. “Joint Monitoring Programme: Water Supply, Sanitation and Hygiene Data - Guatemala.” Retrieved October 21, 2022, from https://washdata.org/data/household#!/table?geo0=country&geo1=GTM

- WorldData. c.2021a. “Telecommunication in Guatemala.” Retrieved October 21, 2022, from https://www.worlddata.info/america/guatemala/telecommunication.php

- WorldData. c.2021b. “Tourism in Guatemala.” Retrieved October 21, 2022, from https://www.worlddata.info/america/guatemala/tourism.php