Abstract

The act of reflection is often considered to be one of the conscious mind – a cognitive act reflecting on one’s lived experience. By adopting principles of reflection defined by Donald Schön in 1983 as reflection-in and reflection-on action, this positioning paper attempts to develop a new methodology for examining and reinterpreting the embodied nature of material reflective thinking. The practice discussed responds to and reinterprets walking acts through methods of stitching-in and stitching-on action. The stitched mark acts as a line that considers concepts of wandering minds, wandering bodies and embodied cognition (Candy Citation2020). Correlations of mind and body wandering through physical and metaphorical space will be drawn on and considered in the context of material thinking and tacit and haptic knowledge. Schön (Citation1983:73) asks the question, ‘In practice of various kinds, what form does reflection-in-action take?’, through this paper I intend to explore what critical-reflective-creative-thinking looks like in a textile practice and examine how the moment of making (stitching/walking) offers opportunities for critical-reflective-creative-thinking with practice.

Introduction

The act of reflection is often considered to be one of the conscious mind – a cognitive act elevated beyond mere thought (Dewey 1910, republished Citation1997). By adopting principles of reflective practice defined by Donald Schön in 1983 as reflection-in and reflection-on action, the research discussed within this paper will attempt to develop a new methodology for examining and reinterpreting the embodied nature of material reflective thinking. Adopting the term embodied cognition (Candy Citation2020) I will discuss how a cognitive reflective practice intersects with embodied material thinking through a creative practice. An embodied approach allows us to experience situations through the whole body (Pink Citation2015; Springgay and Truman Citation2019). Engaging in multi-sensory acts challenges the mind/body divide, deconstructing the hierarchy of sensory experiences and the privileging of sight. Embodied experiences celebrate the haptic and tactile sense of touch; central to a multi-sensory ethnography and acts of doing, concepts of touch have historically been disregarded as unreliable forms of knowledge (Springgay and Truman Citation2019:34-35). Whilst the notion of material thinking and thinking through making are growing areas in academic discourse (Sennett Citation2008; Lange-Bernd Citation2015; Candy Citation2020), the consideration of touch as a form of textile knowledge ‘remains largely underacknowledged’ (Hemmings Citation2023:4).

Schön (Citation1983:73) asks the question, ‘In practice of various kinds, what form does reflection-in-action take?’, through this paper I intend to explore what critical-reflective-creative-thinking looks like in a textile practice and examine how the moment of making (stitching/walking) offers opportunities for critical-creative-reflection. I will argue that stitch is itself a haptic reflective act. The stitched mark acts as a thread that considers concepts of wandering minds, wandering bodies and embodied cognition. Correlations of mind and body wandering through physical and metaphorical space will be drawn on and considered in the context of material thinking and tacit and haptic knowledge.

Through this paper I will unpick the entangled notions of walking, stitch and thinking to propose a concept for embodied and critical thinking with practice, that centrals ideas of touch. I will identify Dewey’s (Citation1997) and Schön’s (Citation1983) concepts of reflective thought as key theoretical concepts underpinning the discussion. Expanding on ideas of reflective thinking on and through making, Sennett (Citation2008) and Candy (Citation2020) will form integral threads of inquiry that intersect with notions of thinking through walking (Macfarlane Citation2013; Solnit Citation2004; Springgay and Truman Citation2019) and textile thinking (Williams Citation2013; Pajaczkowska Citation2015).

The body of work central to this discussion forms part of a PhD by Practice that seeks to explore notions and concepts of engaging with and reconceptualising place through walking and stitch. The thread and path are proposed as concepts for thought, the act of stitching mirroring steps in the process of reflective thinking. The multi-stranded practice seeks to a define new set of methodological approaches for thinking on, in and with practice as a way to reconceptualise place though walking and stitching. The focus of this paper is on the walking-stitch propositions that form part of a critical-reflective embodied material practice that allows for, and creates space for critical-reflective-creative-thinking.

Situating Research: Thinking about Reflection, Walking and Making

Whilst a comprehensive review of the literature associated with thinking, walking and creative practice is not possible here, I hope to contextualise the practice central to this discussion by introducing a short lineage of thinking theory through key thinkers John Dewey (Citation1997), Donald Schön (Citation1983) and Linda Candy (Citation2020), before considering the relationship between walking, textile making and reflective thinking.

Whilst not in the scope of this discussion is it important to acknowledge at this point the extensive research into the mindful nature of walking and making (Wellesley-Smith Citation2015, Citation2021; Springgay and Truman Citation2019; Shercliff and Twigger Holroyd Citation2020). The importance of walking and creativity as an aid for mental health and wellbeing has been promoted by organisations and collectives including WalkingLab and Walking Publics/Walking Arts, an AHRC funded project led by Dee Heddon.

Critical-Creative Reflection

In How We Think (1910 republished in 1997), John Dewey provides an examination of human thought. Aiming to distinguish between the many loose ways we define thinking he provides a differentiation between concepts of idle thinking and reflective thought. Identifying everyday thinking or daydreaming as ‘everything in our heads’ or that ‘goes through our minds’ (Dewey Citation1997:2). This inactive form of thinking is dismissed as idle fancy and trivial recollection. Dewey considers that this is perhaps the most persistent mode of thinking stating ‘more of our waking life than we should care to admit, even to ourselves, is likely to be whiled away in the inconsequential trifling with idle fancy and unsubstantial hope’ (Dewey Citation1997:2). Reflective thought on the other hand is considered to be a more elevated mode of thinking. Described as not only a ‘sequence of ideas, but a consequence – a consecutive ordering in such a way that each [idea] determines the next as its proper outcome, while each in turn leans back on its predecessors.’ (Dewey Citation1997:2-3). The ‘consecutive ordering’ that Dewey discusses suggests a methodical process of working through thoughts, ideas or experiences. Dewey refers to each reflective phase as a step from something to something. Referred to as a term of thought, this flow of ideas becomes a thread or chain that can be followed, it connects events, experiences and thoughts in a way that seems to make sense (Candy Citation2020).

The act of reflection is considered to be a strategic, conscious cognitive process. This notion is expanded on by Donald Schön (Citation1983), who introduced the concept of a reflective practice as the integration of reflective thought with action; defining a reflective practitioner as being ‘someone for whom continuous reflection is an integral part of the way they practice on a daily basis’ (Candy Citation2020:14). Schön’s notions of reflection-in-action and reflection-on-action are central to his theories. He argues that when someone reflects-in-action they are no longer dependent on established techniques, methods and theories of practice, but instead are able to construct their own theories for their individual context (Schön Citation1983:68).

Schön introduces the idea of the ‘medium of reflection-in-action’ (Schön Citation1983:271) as the media, tools, language or methods employed to inform, promote and facilitate reflection – providing the example of the architect’s sketchpad. Within creative practice these artefacts, or mediums-of-reflection will vary depending on practice and may exist as physical, digital, permanent or temporary outputs. Linda Candy (Citation2020) elaborates that in the case of the creative reflective practitioner, these artefacts provide critical insight into the reflective thought process. By reflecting on these artefacts and directing attention to the systems of knowing-in-action and reflecting-in-action the processes of reflective practice can be de-mystified (Schön Citation1983:282).

In The Creative Reflective Practitioner Linda Candy (Citation2020) discusses the importance of the creative works, or artefact, in the reflective process. Whilst the creative outputs are integral to the reflective process, they are not the main focus of attention, rather the making of the works is the act of reflection-in-action and the opportunity for practitioners to search for understanding through making. Candy highlights that it is the context of practice that influences the nature of reflection.

Walking as/for Critical-Reflection

Dewey considers that most thought is inconsequential or unimportant, it could be argued that most walking is the same. Solnit (Citation2004:3) explains ‘that most of the time walking is merely practical, the unconsidered locomotive means between two sites’. This is echoed by Wunderlich (Citation2008) when she discusses purposive walking. Yet she also introduces concepts of discursive and conceptual walking that invite a more considered and thoughtful approach. In Wanderlust, Rebecca Solnit discusses the relationship between walking and thinking referring to Aristotle and the Peripatetic philosophers of Ancient Greece (Solnit Citation2004:15). She cites Jean-Jacques Rousseau who stated ‘I can only meditate when I am walking. When I stop, I cease to think; my mind only works with my legs’ (Solnit Citation2004:14). Robert Macfarlane similarly discusses ideas of walking as thinking, stating that ‘walking is not the action by which one arrives at knowledge; it is itself the means of knowing’ (Macfarlane Citation2013:27).

Walking is often considered a slower form of travel, in a ‘world that is characterised by speed, the idea of taking one’s time […] may seem outdated’ (Bairner Citation2011:372). Walking creates a physical and metaphorical space for the practitioner to think. The pace of thinking falling into a rhythm with the step, suggesting the mind thinks like the feet, at a pedestrian pace of three miles per hour (Solnit Citation2004; Macfarlane Citation2013). If we revisit Dewey’s idea of each ‘term of thought’ as a step in the reflective process, and Schön’s concepts of reflection as a way of knowing-in action; and making a step/walking is the action, then could it be argued that walking is not only a tool for thinking in the peripatetic sense, but also a mode of critical reflective thinking and a reflective practice in itself? As an embodied act it involves the whole body, the experience of making steps propels the mind and body forwards along a path of thought.

Creative-reflective-practitioners who adopt methods of walking are able to reflect both on their own physicality and also the changes within known and familiar places and routes (Philps Citation2021). Charlie Birtles (Citation2022) talks of walking circular routes, implying that they do not consciously have to remember or think about the route, their conscious mind can focus on reflective thinking whilst subconsciously knowing where to go. Similarly, Charles Darwin was known to walk the same looped path in the grounds of his home at Down House, referred to as his Thinking Path (Chubb Citation2011). The habitual walking practice created a space for reflection and observation that informed Darwin’s emerging theories and contributed to The Origin of Species published in 1859. The thinking space created by walking in familiar places allows for the conscious mind to wander in the way the body is wandering through space.

A critical-reflective walking practice invites is an embodied act, walking promotes an engagement with place and foregrounds the experience of moving in place through a whole-body experience (Springgay and Truman Citation2019). Through bodily movement the walker is engaging with multi-sensory experiences to gain knowledge through movement (Merleau-Ponty Citation1962; Romdenh-Romluc Citation2011; Springgay Citation2018). Walking enables the reflective practitioner to explore the interrelation of sensory experiences – the ambient sound of one’s surroundings, other pedestrians and distant traffic; the feel of the ground under foot, change in surface quality, weather, heat from the sun or rain on skin. A critical-reflective walking act requires the practitioner to tune into their bodily consciousness (Romdenh-Romluc Citation2011: 62) and reflect on their sensory experiences. Merleau-Ponty discusses the interrelations of senses when he states, ‘there is not in the normal subject a tactile experience and also a visual one, but an integrated experience which it is impossible to gauge the contribution of each sense’ (Merleau-Ponty Citation1962:119). When reflecting-in-walking one is consciously aware of their proprioception and their relationship to both their own body sense and place. The critical-reflective walker is embodied with a sense of self and place.

Reflective Textile Thinking and Knowledge

Candy calls for a greater understanding of the nature of creative reflective practice from the perspective of the artist-practitioner, particularly through the lens of reflection through making (Candy Citation2020:11), emphasising the complimentary nature of doing and thinking as discussed by Schön (Citation1983:280). Expanding on Schön’s two modes of reflective thinking Candy introduces four further variants – reflection for action, reflection on surprise, reflection at a distance and reflection in the making moment (Candy Citation2020). The fourth mode promotes a model of reflective thinking through the act of making and encourages the critical examination of material thinking and embodied and haptic knowledge. Deleuze and Guattari (1987 cited in Springgay and Truman Citation2019: 41) write that ‘haptic is a better word than tactile as it does not establish an opposition between two senses’; instead promotes a multi-sensory experience that allows for a greater depth of understanding and appreciation of practice. Calling for a ‘methodological study of the different techniques [for] recording, denoting and classifying practice’ Claire Pajaczkowska proposes nine modes of tacit thinking through textiles (Pajaczkowska Citation2015: 92,83-91). Discussing thread as a supporting structure upon which other matter can be threaded, knitted and interwoven, she suggests thread can act as a materialisation of movement. The repetitive looping and knotting of the stitched thread, the untying of knots and unpicking of stitches holds potential to form a metaphor of reflecting, retracing and remaking knowledge.

Stitching like walking, allows time and space for thinking and reflection. The repetitious flow of needle through cloth echoing the steps along a path. The movement of the needle and thread through cloth mirrors the movement of the walker through a place – the movement of people shapes the order and structure of the land in the same way the cloth distorts and changes through the pull of thread; footsteps and worn paths are captured in stitched marks and traces of thread left behind. Jo Vergunst writes about the paths one walks as being embodied with sensory ways of thinking through movement, likewise, the thread acts as a path across the topography of the cloth, embodied with the sensory ways of thinking through making. Through stitching and overstitching the materiality and handle of the cloth changes, it may crease, soften, twist or warp depending on the weight and type. Solveigh Goett suggests that ‘textile knowledge reveals itself in metaphors of folds and threads, knots and weaves in the fabric of life’ (Vergunst Citation2008:124). The hapticality of material handling enables the maker to both touch and be touched (Harney and Moten Citation2013). ‘Textile knowledge is…literally carried as tacit knowledge on [the] skin’ (Goett, Citation2015:124) created by the makers experience of making, doing and handling of textiles. Richard Sennett suggests that knowledge gained through touch is ‘unbounded’ (Sennett Citation2008:152). He considers the notion of the ‘intelligent hand’ that works with the material, making judgements through the fingertips (Sennett Citation2008:152, 153). Hands work intuitively and intelligently, allowing the bodily consciousness to take over (Merleau-Ponty Citation1962; Romdenh-Romluc Citation2011) whilst the conscious mind traces threads of thought, stitching connections between research and practice.

Thinking Space: Creating Situations for a Critical-Reflective-Creative Practice

Often used interchangeably it is important to determine what is meant by space and place. As an abstract concept space implies an area, form and volume, while place is considered to be the centre of meaningful experience situated with human-ness. It is the act of being in and experience space that makes it place (Tuan Citation1977; Springgay and Truman Citation2019). Yi Fu Tuan (Citation1977) suggests that space offers an openness and freedom, considering space as allowing movement. Both walking and stitching facilitate situations for a creative reflective practice through the construction of thinking spaces. These spaces exist in the actual world – the roads, paths and parks where I walk, and the chair in my studio where I sit and stitch. These physical spaces also invoke a metaphorical space – a head-space; where my mind is able to wander and thoughts can start to flow.

I intend to avoid romanticising notions of making and walking, and instead seek to explore places and processes of functionality through a pedestrian practice. Situated within a suburban space, not often associated with a critical creative practice (Mock Citation2009; Philps Citation2021) the walking-stitch propositions discussed explore de Certeau’s (Citation1998) notion of pedestrian as saturated with ordinary-everydayness. Elizabeth Philps (Citation2021) acknowledges the gendering of suburban space as domestic and feminine. The walking practices with the suburbs are often that of necessity, they are functional rather than creative endeavours that punctuate the rhythm of our daily lives. Much like textile making, and particularly stitch work that sits across contexts of textile art and domestic and feminine labour (Parker Citation2019). It is important to recognise the pluriversal perspectives of walking and textile making as both critical-conceptual practices that seek to engage in artistic, cultural and political interventions, and also as a means of requirement, where walking is the only means of transportation and stitch is an economic necessity.

Walking and stitching are explored as conscious and subconscious acts to invoke different types of reflection. Merleau-Ponty (Citation1962) discusses the nature of proprioceptive awareness and the concept of bodily knowledge. Suggesting that when in relevant situations our bodies know what to do and how to act without conscious thought, echoing Sennett’s suggestion of the ‘intellectual hand’ (Sennett Citation2008:152). When in the ‘situation’ for walking and stitching my body knows how to act, what to do and where to go, the subconscious mind is facilitating the bodily movements, making judgements and creating a thinking space that allows the conscious mind to engage in a critical reflective creative practice

It is these thinking spaces that the second part of this paper will examine. Discussing the way in which walking and stitching have become interrelated mediums for reflection-in-action (Schön Citation1983) and reflection in the making moment (Candy Citation2020).

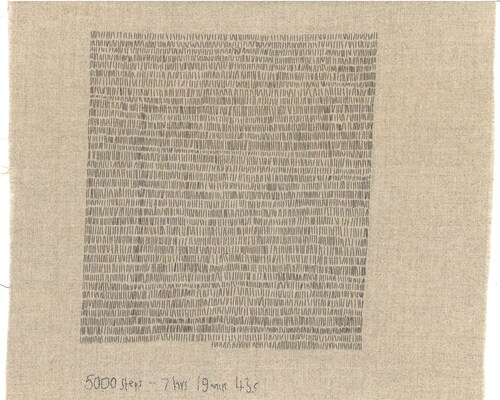

A Stitch-on-Action Proposition: 5000 Steps

5000 Steps () is a stitched sampler that records the 5000 steps made during a 38-minute walk. The stitched sampler took seven hours to complete and tracks each step made during the initial walk. Dee Heddon and Misha Myers (2014, cited in Springgay and Truman Citation2019:41) discuss the demanding, severe and gruelling practice that walking can be. The act of stitching can create its own muscular consciousness and is recorded in the neck, shoulders, hand and finger tips in the same way a walk can be recorded in the toes, heels, knees and back. As I was stitching I felt my bodily position change and my movement became smaller and more restricted as I stitched. The rhythm became smaller and tighter, unlike when I was walking as the rhythm became faster and looser.

When walking I am not physically counting the steps, I use a fitness tracker on my phone so I can record my movement whilst still engaging with the environment. By having to count every stitch I had to be completely conscious of the act of sewing, if I became distracted I lost count. Schön raises question about the effectiveness of reflecting-in-action and its potential to impact the act of doing – in the case of 5000 Steps it was the act of doing (stitching and counting) that impacted my ability to fully reflect in the way I am able to through stitching-in and stitching-on propositions.

Whilst not completed in one sitting, the stitched artefact was created over a several weeks, it still retains the flow of the original walk. Each stitched mark responds to one before it and informs the placement and scale of the following – each stitch (and step) is a consequence of the one that came before – again echoing Dewey’s (Citation1997) suggestion that each reflective stage is a step from something to something.

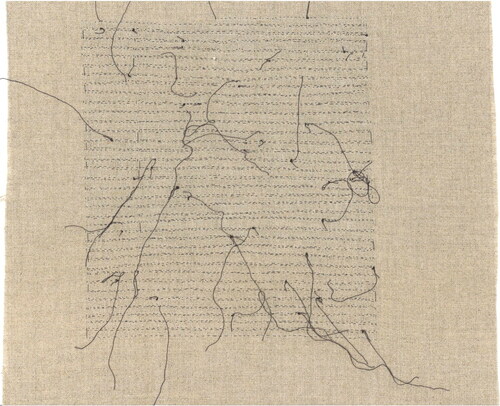

Turning It over: The Reverse of the Stitch

Dewey (Citation1997: 13) suggests turning over ideas in our mind as a means to reflect and uncover additional information. With that in mind I turn to the back of the stitched artefact (), the piece that is usually unseen by the viewer, yet often calls to the maker. As a textile practitioner I intuitively turn something other, inspect how it was made, what it was made with. When turning over 5000 Steps I can see the journey of the thread. The loose threads that tell the story of thoughts not resolved, the small stitches between the ‘steps’ on the front of the sample are traces that hold reflective thoughts together, yet have not been examined in their own right.

When the focus is on the ‘front’ of the piece, the reverse can seem inconsequential. However, these unacknowledged-at-the-time-of-making marks are not inconsequential, they are integral to the reflective process, they are the material that aids reflection. Tim Ingold (Citation2007) suggest that all things are made of lines, and defines lines as two categories, threads and traces. Through examining the reverse of 5000 Stitches we can start to reflect on the traces of a reflective practice through the lines of thread embodied with reflective thought.

Walking-with-Place | Stitching-in-Action

Adopting Schön’s (Citation1983) models for reflection-in and on-action and expanding on Candy’s (Citation2020) variant of reflection in the making moment, the stitch-in-action and stitch-on-action propositions intend to contribute to the development of new a methodological approach for material reflection.

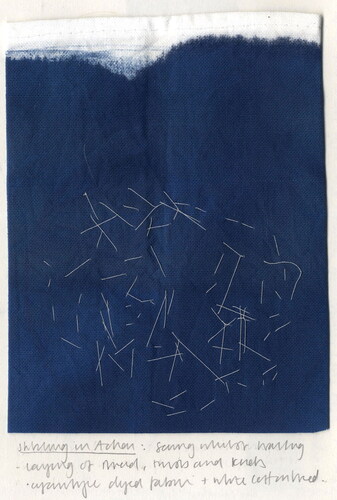

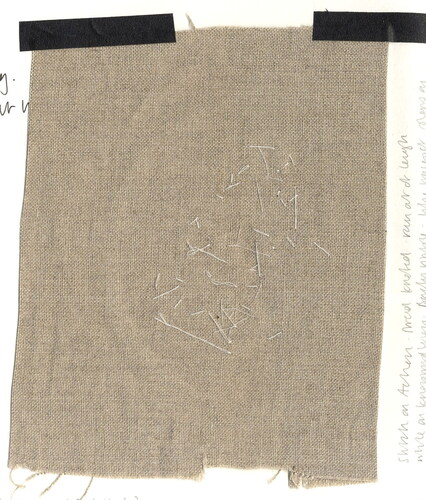

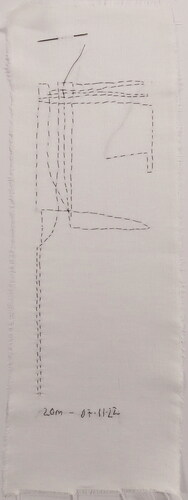

Through stitch-in-action I am sewing whilst walking (), the hand and feet mirror each other, the thread knots and twists, yet I do not focus on the stitched marks being made. I try to engage in a form of bracketing to suspend my judgement and allow myself to respond to sensory cues intuitively. To allow myself to full embody the walk and to engage in a creative reflective practice I do not have planned routes and allow myself to be drawn by sensory cues. Merleau-Ponty contends our comprehension and understanding of the world and our experiences is through the body (Merleau-Ponty Citation1962: 234-35). I allow myself to respond to the sensorial qualities of the world around me, my conscious mind is focused on the sound of traffic, change in terrain, other road and pavement users. It is the sounds smells and sights that draw me in different directions as I walk through the suburban space, allowing the other human and non-human agent to direct where I go, I am walking with place.

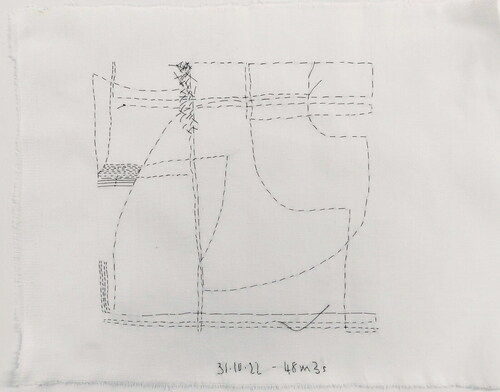

Using an embroidery hoop to keep the fabric taught, my hands intuitively handle the fabric and needle, passing the fabric from hand to hand, turning the hoop as I walk. I avoid looking at the fabric and thread so as not to consciously direct my hands whilst they stitch. Through stitching whilst walking with place I hope to capture what it means to move, respond to, and reflect in a space. The resulting stitched pieces are embodied with the time and place of their creation (, ).

Working-with-Cloth | Stitching-on-Action

Whilst walking I am capturing the sound of the movement of my body in place using an audio recorder. The sound recording is then used to create an audio walk that I re-listen to whilst stitching. Stitching for the same length of time I was walking the unplanned stitched route echoes the unplanned walked route. The stitched marks re-capture my movement through and with place. I am able to revisit and reflect on sounds I did not originally pick up on and will re-listen and re-stitch multiple times to explore further reflections. This act of stitching-on-action allows time to reflect on my walking act, I am becoming aware of my own physicality, speed and pace of movement in response to place. In contrast to the stitching-in-action proposition, stitching-on-action requires me to consciously engage in the act of stitching whilst listening to the audio walk. Unlike the previous walk I do not use an embroidery hoop to hold tension in the fabric, instead I respond to the movement of the cloth in the same way I responded to the sensory cues of place. As I hold the fabric with my left hand it creases and folds, creating an uneven surface, the stitched lines start to curve. I create several stitches on the needle before pulling the thread through, the thread knots and twists as it pulls through the cloth. Whilst I am consciously stitching, I am not consciously controlling the needle and thread, rather I am working with the cloth in a collaborative practice ( and ). In the same way I responded to the sensorial qualities of place, I am responding to the vital materialities of the cloth (Bennett Citation2010).

Conclusion: Thinking-with-Practice

Through this paper I have discussed how a cognitive reflective practice intersects with embodied material thinking through a series of walking-stitch propositions, proposing a new methodology for examining and reinterpreting the embodied nature of material reflective thinking. The practice of walking-stitching creates space for a critical-reflective-creative mode of thinking that encourages the artist-practitioner to engage in a multi-sensory experience of being. By responding to the vital materialities of the non-human agents of practice (place, cloth, thread, needle) I am engaging in a collaborative process; working and thinking with a walking-stitch practice. The stitched artefacts become ‘a materialising of thought’ (Vaughan Citation2007); a visual articulation of the act of critical and reflective thinking. Anni Albers considered making with materials as a ‘superior kind of thought’ (cited in Mitchell Citation1997:7), and whilst the stitched samplers become useful tools for reflection in and on-practice, it is the process of thinking and reflection-with-practice through stitching and walking that is central to the discussion.

Rather than offering answers to Schön’s question, ‘In practice of various kinds, what form does reflection-in-action take?’ (Schön Citation1983: 73), the propositions presented here highlight areas for further investigation of the relationship between practitioner and practice through an embodied experience. Schön stated that a study of reflective practice was critically important and spoke of the ‘scientist’s art of research’ (Schön Citation1983: 69). This body of work contributes to a study of the ‘artist’s science of research’, and responds to Candy’s (Citation2020) call for more understanding of the dimensions of reflective practice via the practitioner’s voice.

Disclosure Statement

The author reports there are no completing interests to declare.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Faye Power

Faye Power is a lecturer in Textiles and Surface Design at the University of Bolton working across both undergraduate and postgraduate programmes. Research interests include socially conscious practice; the relationship between creativity and wellbeing; media, materiality and immateriality and reflexive-material thinking. Faye is currently undertaking a PhD by practice developing multifaceted methodologies for capturing and examining material and immaterial sensory experiences. [email protected]

References

- Bairner, A. 2011. “Urban Walking and the Pedagogies of the Street,” Sport, Education and Society, 16(3): 371–384.

- Bennett, J. 2010. Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

- Birtles, C. 2022. “Making Meaning Live Highlights 2” [Podcast]. Available online at: https://ruthsinger.com/2022/08/18/making-meaning-podcast-episode-23-highlights-from-making-meaning-live-with-amy-twigger-holroyd-claire-wellesley-smith-lokesh-ghai-and-charlie-birtles/ (accessed 07.11.2022).

- Candy, L. 2020. The Creative Reflective Practitioner. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Chubb, S. 2011. “Thinking Path.” [Online] Available from: https://www.shirleychubb.co.uk/exhibitions/thinking-path/ [Accessed 20 October 2022]

- De Certeau, M., 1998. The Practice of Everyday Life, Translated by Rendall, S.B. London: University of California Press.

- Dewey, J. 1997. How We Think. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications Inc.

- Goett, S. 2015. “Materials, Memories and Metaphors: The Textile Self Re/collected.” In J. Jefferies, D. Wood Conroy and H. Clark (ed.) The Handbook of Textile Culture, pp. 121–136. London: Bloomsbury.

- Harney, S. and Moten, F. 2013. The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning and Black Study. New York: Minor Compositions.

- Hemmings, J. 2023. The Textile Reader. 2nd Edition. London: Bloomsbury.

- Ingold, T. 2007. Lines: A Brief History. London: Routledge.

- Lange-Berndt, P. 2015. Materiality. London: Whitechapel Gallery and Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Macfarlane, R. 2013. The Old Ways: A Journey on Foot. London: Penguin.

- Merleau-Ponty, M. 1962. Phenomenology of Perception. Translated by Smith, C. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

- Mitchell, V. 1997. “Textiles, Text and Techne.” In J. Hemmings (ed.) The Textile Reader. 2nd Edition, pp. 5–11. London: Bloomsbury.

- Mock, R. 2009. Walking, Writing and Performance: Autobiographical Texts by Dierdre Heddon, Carl Lavery and Phil Smith. Bristol: Intellect Books.

- Parker, R. 2019. The Subversive Stitch: Embroidery and the Making of the Feminine. London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts.

- Pajaczkowska, C. 2015. “Making Known: The Textiles Toolbox – Psychoanalysis of Nine Types of textile Thinking.” In J. Jefferies, D. Wood Conroy and H. Clark (eds), The Handbook of Textile Culture, pp. 79–94. London: Bloomsbury.

- Philps, E. 2021. “Just to Get Out of the House: A Maternal Lens on Suburban Walking as Arts Practice,” Journal of Cultural Geography, 38(2): 286–305.

- Pink, S. 2015. Doing Sensory Ethnography. 2nd Edition. London: Sage.

- Romdenh-Romluc, K. 2011. Routledge Philosophy Guidebook to Merleau-Ponty and Phenomenology of Perception. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Schön, D.A. 1983. The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action. London: Maurice Temple Smith.

- Sennett, R. 2008. The Craftsman. New Haven, CT and London: Yale University Press.

- Shercliff, E. and Twigger Holroyd, A. 2020. “Stitching Together: Participatory textile making as an emerging methodological approach to research,” Journal of Arts & Communities, 10(1&2): 5–18.

- Solnit, R. 2004. Wanderlust: A History of Walking. London: Verso.

- Springgay, S. and Truman, S. 2018. Walking Methodologies in a More-Than-Human World: WalkingLab. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Tuan, Y. 1977. Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Vaughan, L. 2007. “Material Thinking as Place Making,” Studies in Material Thinking, 1(1). https://materialthinking.aut.ac.nz/sites/default/files/papers/Laurene_0.pdf [accessed 3 April 2023].

- Vergunst, J.L. 2008. “Taking a Trip and Taking Care in Everyday Life.” In T. Ingold and J. L. Vergunst (eds.), Ways of Walking: Ethnography and Practice on Foot, pp. 105–121. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Wellesley-Smith, C. 2015. Slow Stitch: Mindful and Contemplative Textile Art. London: Batsford.

- Wellesley-Smith, C. 2021. Resilient Stitch: Wellbeing and Connection in Textile Art. London: Batsford.

- Williams, R. 2013. “Sewing Proust: Patchwork as Critical Practice,” Journal of Textile Design Research and Practice, 1(1): 43–55. DOI: 10.2752/175183513X13772670831119.

- Wunderlich, F.M. 2008. “Walking and Rhythmicity: Sensing Urban Space,” Journal of Urban Design, 13(1): 125–139.