Abstract

This study situates fashion history in the context of art market research to explore the assetization of luxury clothing. Art markets and the luxury fashion industry developed in tandem and yet there have been no cultural economic studies on fashion as a form of art. This study takes a data driven approach to assessing the monetary value of clothing sold at auction at Christie’s primarily in the twenty first century. The results of this study confirm with a high degree of statistical significance that fashion auctions at Christie’s, Inc. auction house have become increasingly lucrative since the twentieth century. Moreover, the results of this study show that there is a statistically significant financial incentive to purchase and hold onto certain luxury clothing items from the canons of fashion history. This study provides a baseline on which to explore increasingly atomized configurations of value with respect to material culture from fashion history.

Introduction

This empirical study is premised on the idea that fashion is a form of art. There is an abundance of research and writing that foregrounds the connection between fashion and art. Kim’s is an important primer on the polemic.Footnote1 In fashion and art media, Menkes’ article explored “the symbiosis that links high fashion designers and artists” throughout the twentieth century.Footnote2 Elizabeth Wilson’s seminal exploration of fashion and modernity underscored the chasm between “high art” on one hand and “low art” due to the expansion of mass production in modernity.Footnote3 The mass production of clothing, Wilson argues “links the politics of fashion to fashion as art” (8). Wilson situates fashion at the apex between the avant-garde on one end of the spectrum and popular culture on the other. The culture industry, a term coined by Horkheimer and AdornoFootnote4 addressed the effect of mass production on the commodity form and by extension, the expansion of the chasm between “high” art and “low” art. Wilson similarly uses the mechanisms of reproduction that were defining characteristics of the twentieth century to offer parallels between fashion and photography, both forms of art that are “on the threshold between art and non-art.” At the heart of this discussion of fashion and art, is a larger question about the nature and constitution of art more generally—what then is art? Miller’sFootnote5 picks up on some of these larger questions.

Where the twentieth century saw the expansion of mechanization and mass production that gave rise to the commodification of the culture industry, the idea of assetization, the process by which a thing becomes a store of capital, has similar corollaries in the twenty first century.Footnote6 Assetization is an increasingly important area of research in digital markets in technoscientific capitalism. If an object (conceived as a commodity in the twentieth century) becomes an asset (conceived of as a thing capable of future revenue generation in the twenty first century) then purchasing goods becomes a form of capital investment. The results of this study suggest that there is an opportunity for consumer behavior to bend toward longevity. While developing a study of clothing predicated on an underlying logic of financial reward is not unproblematic, clothing has become increasingly disposable and therefore, devalued in the twenty first century. This study looks at the underlying dynamics of art markets to see if there are ways in which the study of collectible markets can shed light on the re-inscription of value in the fashion system.

From the red carpet to the runway, the secondhand trade of clothing remains as culturally important as it is lucrative. The sale of luxury clothing at auction gained steam in the latter part of the 20th and early 21st centuries and this era of fashion consumption, purchased under the auctioneers’ hammer, offers important information about the collection and consumption of fashion history.Footnote7 As countries around the globe address pressing issues related to waste in the fashion supply chain, there is a growing awareness about the economic implications of extending the life of clothing. Do fashion auctions of the early twenty first century offer clues to the process of signification and monetary valuation that could shed light on a more sustainable fashion future?

At the outset it is important to foreground the ambivalent nature of clothing design as both a trade as well as an art form. In what follows, we touch on the advent of authorship and connoisseurship in luxury fashion consumption. Drawing on Kawamura’sFootnote8 distinction between clothing—the tangible object, to fashion –the symbolic cultural object, the following paragraphs touch on the advent of authorship, connoisseurship, and the process of singularization that is both unique to luxury fashion consumption and emblematic of the marketization of art history. The complexity of secondary markets as they relate to the dynamics of capital and artistic production have been discussed in a wide array of literature yet the study of fashion in an art historical and marketized context, remains under-explored in both cultural economics as well as art and design history.

Overview of the development of art markets and the luxury fashion system 1400 to present

While VasariFootnote9 was writing the Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects in Renaissance Italy in the sixteenth century, custom-made clothing of exceptional fabric was made and worn by the same cultural elite who commissioned and funded the works of art that formed the bedrock of Renaissance art historiography. Makers and purveyors of fine clothing were considered financial intermediaries of important family investments. Clothing was often custom, hand-crafted with hand-woven fabric including gold brocades, velvets, damasks, and brocatelles. Previous research in this area shows that the rigattiere of TuscanyFootnote10 and the strazzaruoli of VeniceFootnote11 were traders of luxury clothing and therefore acted as a dealer or intermediary of singular, hand-made garments. Clothing was so valuable on secondary markets and so carefully regulated according to sumptuary laws, that it was often taken apart and stored separately to protect important assets in a family estate while simultaneously circumventing sumptuary laws.

In the Early Modern period, London and Amsterdam were the hubs of secondhand clothing trade.Footnote12 Clothing was extremely expensive, and the materials and construction were of tantamount importance as expressions of status. The central commercial actors moving goods through secondary markets varied according to the region and social infrastructure. In the early modern period, cloth was so valuable that guild systems emerged to regulate and dictate who was allowed to cut cloth (para. 2).Footnote13 The early guilds carefully regulated who could procure fabric, cut it, and make clothing. These regulations evolved into a more modern guild system that gave rise to the earliest idea of a fashion designer. Dating back to the 1700s in France, mercers or fabric sellers were critically important gatekeepers to the latest styles. Being neither dressmaker nor weaver, the mercer was the intercessor between the weaver and customer and as such, cultivated an aura of aesthetic authority. As a result of the guild system, these divisions of labor continued throughout most of the eighteenth century with clearly demarcated roles in the commercial production of clothing. It was not until 1776, when the guild system was reformed by Louis XVI, that the marchands des modes were more formally recognized as a corporation unto themselves and charged with the creation of clothing for ordinary as well as extraordinary clients.Footnote14

Modistes, or dressmakers, were commissioned to create clothing for high profile clients. Concurrently, the first fashion magazines appeared in the 1770s and further exacerbated the “growing dichotomy between formal and informal dress.”Footnote15 Sumptuary laws had long been thwarted throughout the eighteenth century and their formal repeal in France coincided with the denunciation of the monetarist aristocratic system.Footnote16 While the role of clothing in reinforcing social hierarchy did not disappear, the latter half of the eighteenth century ushered in a new era of social distinctions communicated through dress practices.

Dressmaker to tastemaker

Beverly Lemire’s book Global Trade and the Transformation of Consumer Cultures (2018), offers an important and significantly more global lens into the use of clothing as an asset. Lemire underscores the ubiquity of secondhand clothing consumption that was directly tied to international trade in the 17th and 18th centuries. She cites examples of the use of clothing as an asset in Early Modern history in Japan, China, the Iberian Peninsula, West Africa and others. Each regional history developed in parallel with colonial trade routes and complex and highly nuanced sumptuary laws. Lemire points out that Even Adam Smith in, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1804) discussed the entrepreneurial use of used clothing as a form of currency (20). That said, because France was one of the more populous regions in Europe in the eighteenth century, the use of clothing was of particular importance for rearticulating class structures in a region transitioning from old ways (agrarian) to new (industrial). In discussing the use of French fashion as a tool of “cultural propaganda”, Historian RibeiroFootnote17 writes, “Not only was dress a unifying factor but it was also a civilizing one in an age in which Reason was the prevailing goddess.” (6)

In Daniel Roche’s important book, The Culture of Clothing (1994), the second section is devoted entirely to the economy of private wardrobes. Writing of the web of cultural interactions between production and consumption in Paris in the ancien régime, Roche documents the economics of the Parisian clothing system. In Paris, Roche writes, “the manufacture of clothes was also the manufacture of cultural signs” (1994, 68). Roche’s analysis touches on hierarchy in consumption patterns among the nobility, wage earning citizens, domestic workers, artisan crafts people, and professional workers in offices. Roche demonstrates that the percent of total moveable wealth accounted for by clothing and linen was notably higher from wardrobes in 1789 compared to 1700. Perhaps most interestingly, in both 1700 and 1789, the percent of total moveable wealth accounted for by clothing and linen was at least three to four times higher for wage-earners and artisans than for nobility, domestic workers, or office holders (94). Moreover, the value of women’s wardrobes was observably higher than the wardrobes of men. By 1789, the value of people’s wardrobes (except for the merchant and craft workers) had increased far greater than the value of people’s other expenditures. Owing to transformational changes in social habitus, the excesses of the ancien régime ushered in a new era of consumerism, particularly related to dress practices.

Each of these historians locate the economic enterprise of buying and selling clothing—what Beverly Lemire calls “the calculus of clothing”—as central to the formation and subsequent distillation of the fashion system that exists today. Arguably, these economic structures of production and guild regulation precipitated the advent of the modern fashion designer.

The fashion designer

In the latter half of the eighteenth century, dressmaker Rose Bertin counted over 1500 clients, including most notably, Marie Antionette. Bertin’s signature style and her extensive client list of royalty and nobility made her the first celebrity fashion designer. Bertin’s lavish creations were explicitly made for court appearances and accordingly, astronomically expensive. Bertin was also known to create samples or prototypes which she regularly debuted to her clients, even while exiled in England during the Reign of Terror. Immediately following the French Revolution, the Empress Josephine’s primary couturier, Leroy, was similarly famous for his elaborate postcoronation gowns.Footnote18 By the early nineteenth century, the advent of the celebrity fashion designer was well underway.

While Rose Bertin was considered the first celebrity designer, the birth of haute couture is often attributed to Charles Frederick Worth.Footnote19,Footnote20 A skilled businessman and former marchands des mode, Worth is credited as being the first clothier to attach his name to his creations. This was a pivotal moment in fashion history that presaged the art of branding that would eventually come to define the luxury industry. While there were certainly fashion trends and sought-after dressmakers prior to the 18th and 19th centuries, the House of Worth became the first major fashion empire due in no small part to the ways in which “Worth redefined the creative process, with the presence of the label serving as an added value, the indelible mark of the artisan-couturier turned artist-couturier.”Footnote21 Worth’s clothing labels changed over the years according to the changing tides of his business; however, he remained adamant that an artist should sign their work. This was a pivotal moment in fashion history as labels became a sign of authenticity.

Inspired by Worth, many other designers also began using labels in their clothing. Simultaneously, this chapter of fashion history overlapped with the establishment of copyright laws for art works in France. The copyright regulations for art came into force in the period between 1865-1870 and in 1884 they began to be applied to women’s clothing and jewelry.Footnote22 Furthermore, the allusion between a fashion designer and that of a physical house was instrumental in the defining and refining of brand DNA. Where Charles Worth was the first designer to effectively sign his work, in 1870 he changed his label to read Maison Worth. The idea went beyond semantics, the use of a house was a departure from the tailor or tradesperson who made home visits or worked out of a small shop. Houses are personal spaces that reflect the lived experience of the inhabitant and Maison Worth was no exception to this idea. In his maison, “Worth devised an elaborate setting for the reception of his creations that enhanced the personalized aspects of his business and obscured the commercial and industrial dimensions”.Footnote23 As the first modern fashion designer, Worth became the arbiter of taste among the elite in Europe as well as the United States.

Fashion education and the cultivation of aesthetic vision

Following on the heels of Worth’s transformation of the industry, the first fashion schools or academies emerged in the early part of the twentieth century. In the nineteenth century, most luxurious clothing was still handcrafted owing to the expense of working with the expensive silks that required delicate hand-finishing. In this way, the making of clothing was still considered a craft until the ready-to-wear democratization of fashion at the turn of the century. While land grant schools in the United States offered a formal education in Home Economics beginning around the turn of the twentieth century, their sewing classes were primarily oriented toward the domestic sphere. It was not until the 1930s that the École Superièure de la Couture, the educational arm of the Chambre Syndicale de la Couture opened in Paris and the Royal College of Art (RCA) opened in London.Footnote24

Upon the success of The Great Exhibition in London in 1851, applied art gained a significant foothold in the cultural and educational system in England and the RCA was built in tandem with the Victoria and Albert Museum.Footnote25 The first RCA graduate in fashion, Muriel Pemberton, would later go on to found the first fashion program at the St. Martin’s School of Art.Footnote26 The fashion program at the School of Art eventually became Central Saint Martin’s (CSM) which continues to be one of the premier fashion design institutions in the world.

Jane Hegland’s extensive list of international design schools begins in the fashion capitals of London, Paris, and Milan, and radiates out to offer a wide-reaching lens of the international fashion education system.Footnote27 From the naissance of a design education in the early part of the twentieth century, Hegland highlights fashion programs in over 70 countries throughout the globe from vocational or technical schools to four-year liberal arts institutions of higher education. McNeilFootnote28 points to the period immediately following World War II when the fashion design school became a place where the mythic role of the designer as translator of aesthetic vision from sketches to toiles, was ingrained. In this way, toiles or muslins functioned like artist studies or preliminary sketches. The marriage of technique and artistic ingenuity put the designer on a par with the artist.

The early fashion schools were modeled on trade schools and apprenticeship models of the guild system, where designers were taught technique as well as the emerging importance of the development of aesthetic vision. While trade schools were often municipally funded and focused on techniques that were of use in the textile and needle trades, fashion schools were private establishments that offered a heightened degree of social mobility through the cultivation of a discerning aesthetic acumen. Apprenticeships, much like the guild system of centuries prior, were the primary method of breaking into the burgeoning fashion business at the time. Arguably, the importance of the apprenticeship remains one of the most significant training opportunities as well as barriers to entry to the industry today. The advent of fashion academies occurred contemporaneously with art museums’ earliest advances in the collection and exhibition of archival fashion collections. Today, fashion exhibitions and archives are among the most fiscally successful components of the world’s largest art museums.

The rise of the fashion exhibition

The first international fashion exhibition was held in 1900 in Paris and in the coming decades, museums would come to increasingly dedicate space and resources to the acquisition of clothing. Many of the clothing collections in major museum institutions grew out of the philanthropic donation of private archival collections.Footnote29 The role of fashion within the canons of art history and venerable international museums has long been a subject of debate. AndersonFootnote30 explored this polemic in “what might appear as an outmoded ideological battle between “high culture” and popular culture” (374) evidenced by sharp criticism of early fashion exhibitions as prioritizing entertainment over education and thereby defiling museums’ didactic mission. While this debate is not over, today, it is more widely understood that fashion exhibitions generate record-setting patronage along with revenue generated through ticket and licensed museum merchandise sales.Footnote31 Fashion exhibitions have drawn large audiences and become a mainstay of museum revenue generationFootnote32 for noteworthy exhibitions. Commercial considerations aside, fashion scholars and curators in the early part of the twenty first century have made great strides in advancing both the aesthetic and intellectual presentation of fashion in museum exhibitions. Louise Wallenberg points out that once a garment is “selected and saved in a museum collection, and displayed for an audience, it is not only its historic, social, and symbolic value that increases—so does its economic value”.Footnote33 At the epicenter of this study is the correlation between the historic, social, symbolic and economic value.

From the first fashion exhibitions at the turn of the twentieth century to the contemporary digital era, museums, archives, and libraries, have emerged as “central entities in the affirmation and legitimization of culture as both a symbolic and economic value”.Footnote34 The digitization of fashion and design archives plays an active role the formation of collective memory and shared cultural heritage. Scholar FranceschiniFootnote35 makes a prescient reference to Marizio Ferraris’ concept of “documentality” in a paper about the function of digital fashion archives in the preservation, classification, and dissemination of fashion heritage. Francheschini evokes “documentality” as “documents are not all accessory; rather they are fundamental in shaping both individual and collective memory”. In this way, fashion archives play an active role in the preservation of legacy.

House codes

House codes encompass the series of visual cues that reverberate from a design house and solidify a claim to a particular aesthetic landscape—fabric, color, prints, silhouette, etc. Chanel and bouclé, Pucci’s colorful prints, Courrèges and space age, modernist silhouettes, Paco Rabanne and the use of metallics, Valentino red, and Burberry plaid, are just a few examples of house codes. This can also encompass the use of symbols and branding—the Fendi F, Versace’s use of the Medusa Head, or Gucci’s horsebit. House codes echo throughout the entire aesthetic journey of buying from a brand. These signifiers can include packaging like the Tiffany & Co. blue box, Hermès signature orange, or Lanvin’s light blue. While house codes can encompass branding, the research here is primarily focused on the development of house codes in the design of clothing. The fashion show became one of the most important avenues by which to present clothing and an aesthetic vision.

The earliest fashion shows emerged primarily in Paris in the nineteenth century to sell clothing to international buyers. Caroline Evans makes the important point that the “Paris trade was, however, an unusual one, in that it exported not goods but ideas, in the form of model dresses and the right to reproduce them” (2013, 2). The fashion shows’ exportation of ideas as opposed to objects, was a critical point in the development of the fashion industry today. What was being exported was a base idea upon which to translate the design house’s vision to a global community of patrons. The spread of western fashion was perpetuated by designers and their entourage of models making “whistle-stop tours of foreign cities, staging fashion shows in department stores and holding press conferences”.Footnote36 The point of these tours was primarily promotional with the goal to cement licensing deals and sell paper patterns. This brand of fashion evangelism was buttressed by an ever-expanding fashion press in the early half of the twentieth century. The fashion show went from being a trade show to a form of spectacle, in the 1920s where “Harper’s Bazar played a significant role in reconceptualizing the French fashion show as a social event”.Footnote37 The 1920s were characterized by a changing class consciousness in which the presentation of clothing became more assimilated into everyday aspects of social life.

During her tenure at the New York Times (1925-1955) Virginia Pope of the New York Times was cited as one of the first journalists to make fashion “a topic of serious newspaper coverage with the attendant responsibilities for accuracy, objectivity, and fairness.”Footnote38 By the 1950s, the nascent fashion press argued that fashion ought to be covered in the newspaper in the same way that sports were covered. Unlike sports coverage of games and scores, fashion reporters would cover fashion shows each season and provide up-to-date commentary and analysis.Footnote39 Previously, only buyers representing private clients, boutiques, and department stores were invited to attend the in-person live shows.

Both the fashion show and the fashion critic fueled the development of and adherence to refined brand ideals and established what we now think of as house codes or design DNA. Critical luxury studies scholar, ArmitageFootnote40 writes “Codes function like enclosures…as they frame the possibilities for understanding”. The process by which images, colorways, fabrics, and silhouettes become codes is rooted in the generative and reiterative processes of meaning creation. Over time, the methodical reproduction of these signs grounds brand ideals from decade to decade and distinguishes the meaning of one design era from another. The linkage between monetary value and the larger meaning of a particular brand or designer is itself emblematic of the ways in which clothing eulogizes moments of historic and cultural import and speaks to the structure and functioning of society.

Changes in patronage for luxury fashion secondary markets

The larger history of secondary markets in fashion transcends borders and socioeconomic contexts, it is important however to note the sociocultural subtext of luxury fashion’s secondary markets as they emerged in the latter half of the twentieth century to foreground the sale of luxury clothing at auction in the latter half of the twentieth century. Writing of the luxury second-hand couture market in Canada in the 1950s, scholar and curator Alexandra Palmer documented the three charity-run consignment stores and five privately held stores that made up their robust luxury secondary clothing market.Footnote41 Some of the most notable secondhand clothing sales in Toronto in the 1950s and 1960s were annual events such as the Toronto Symphony Orchestra Rummage Sale or Junior League of Toronto’s Opportunity Shop both of which were a source of revenue generation for their respective organizations. Palmer points out that the relationship between Toronto’s luxury consignment shop and high-end department stores was hardly acrimonious. Many of the department store’s elite clientele were also members of Toronto’s philanthropic community who organized and staged secondhand fashion shows and rummage sales. “Stores’ support of their elite customers was of mutual benefit, as these women were their most socially important clients.”Footnote42 In some instances, department stores even donated unsold clothing to the secondary shops in addition to providing retail supplies and serving as partners in fundraising and promotion. While research suggests that women of all socio-economic classes took part in buying secondhand luxury clothing “for socialites, a stigma was attached to profiting intentionally from the sale of one’s wardrobe”.Footnote43 The 1970s, by contrast, ushered in a new era in high-end luxury clothing sales at major auction houses like Sotheby’s.Footnote44

Many of the early clothing auctions of vintage couture in New York and London were considered failures with low hammer prices and many unsold lots. The auctions were primarily attended by museum curators and professional collectors as “private buyers were not yet tuned to the opportunity”.Footnote45 As such, it was decided to only feature clothing auctions in cases where provenance was a principal component and even then, it was preferred that the auction proceeds go toward a charity. Fashion auctions functioned as a form of pro bono outreach as opposed to a source of revenue generation.

It was not until the 1990s that the social affinity for secondhand luxury had transformed into an important prestige market untethered from the social mission of charity sales. Heretofore, the clientele attending fashion auctions was typically made up of institutional investors and professional collectors. Writing on the overlap between dress and the art market in the latter half of the twentieth century, Stephanie Lake points out “ready-to-wear houses, newly focused on incorporating vintage designs into their collections also became avid buyers”(2010, para. 2). Today, company archival collections are ubiquitous in the fashion industry and they continue to serve as important sources of inspiration, innovation, and brand identity.

The period from 1996-2000 was a pivotal moment in luxury fashion auctions. There were many luxury fashion auctions and headlines like “Giving Haute Couture Auction Cachet”Footnote46 and “Frock Options: Haute Couture or Vintage Ready-to-Wear—Auction Houses are Profiting off Runway Inflation”Footnote47 were featured in trade publications and The New York Times, alike. Lake points to the 1996 Sotheby’s sale of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis’ estate as a turning point in the secondary sales of luxury clothing. The Kennedy Onassis sale garnered more than 5 times the preauction estimates and the total sale yielded over $34 million. Also, in 1996, a collection of Princess Diana’s dresses went under the hammer at Christie’s where several garments broke records for clothing sold at auction. The sale included 79 dresses which on average, each sold for $41K. The highest grossing dress of the sale went for $225,500 while the hammer price for several other dresses went for closer to the $20K-$40K range. Importantly, the sale drew in many first-time buyers many from the southern and midwestern United States who were captivated by the British monarchy. By contrast, Richard Martin, then Director of the Costume Institute at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, discussed the “associational value” of Diana’s dresses but offered a tepid appraisal of the collection saying that while “Diana’s dresses had “associational value” because they were worn by her, they did not, in his view have historic or artistic value”Footnote48. The auction of Diana’s dresses was held in New York and the pre-sale viewing of the lots brought in “everyone from a Jersey City 6-year-old in a rhinestone tiara to Manhattan society to Joan Rivers” (1997, para. 11). The wide appeal of these landmark fashion auctions signaled the beginning of an era in which luxury clothing captured the attention of collectors outside the traditional fashion cognoscenti.

The appointment of Tiffany Dubin as the first fashion director at Sotheby’s in New Yok was a defining moment in legitimizing the fashion auction within the canons of art auctioneering.Footnote49 This was not the first moment that venerable auction houses recognized the importance of fashion. The Sotheby’s London flagship had a fashion department for 20 years prior to the mid-1990s however they focused largely on historic dress and textiles. Meanwhile, The William Doyle Galleries (now Doyle Auctions) held semi-annual couture sales in New York and were on the forefront of the contemporary fashion auction. Doyle Auctions’ sales were known to have a broad client base of collectors and amateurs alike, and to feature high volume auctions with over 800 lots.Footnote50 The appointment of Tiffany Dubin was notable because auction houses began selling more contemporary clothing; in some cases the clothing was fresh from the couture or ready-to-wear runway. The 1990s were a pivotal moment where auctions of clothing from the recent past “came into its own as an art form”.Footnote51 The collision of the traditional auction and contemporary culture ushered in a new era in the sale of vintage luxury clothing.

Methods

Heterogeneity versus homogeneity

The data collected in this study dates from 1998 to 2019. This is the data that was publicly available on Christies.com. In the latter part of this period, Christie’s began focusing their auctions on celebrity exclusive auctions or the sale of handbags. In this study, the distinction between heterogeneous versus homogeneous objects is fundamentally important to the construction of a price index or modeling system. The manufacture of luxury clothing presents a unique set of criteria by which to establish the heterogeneity or homogeneity of clothing. For the sake of analysis, an original oil painting sold at auction is considered heterogenous, or one-of-a-kind. Whereas a run of prints might be considered homogenous or able to be analyzed in runs due to their visual similarity. This same dichotomy holds when it comes to clothing. Made-to-measure, numbered, haute couture garments are unique unto themselves whereas, other manufactured ready-to-wear clothing was created in runs and graded according to size variation. Between the singular commissioned couture garment and the artisan industrial production of ready-to-wear clothing is a spectrum of manufacturing techniques which complicate the construction of an index. For the sake of the data analysis in this study, and because used clothing takes on a unique non-fungible narrative, each lot is treated as heterogenous and is compared and contrasted according to its constituent parts (designer, year of manufacture, clothing typology, etc).

At the outset, it was important to establish the criteria most relevant to this study. Because we attempt to assess price change over time of luxury fashion goods, the essential components of a garment’s provenance were critically important in data collection and analysis. The distillation of fashion house codes and design directorship have therefore become the primary attributes of study in this examination. Ascertaining both brand (referred to as “Label” in the data) as well as designer (referred to as “Designer” in the data) are fundamental to questions of a garment’s historic and social import.

Christie’s data

Christie’s, Inc. auction house was chosen as the source of auction data for this study. Reitlinger’sFootnote52 used data from Christie’s that was subsequently used in multiple cultural economic journal articles including studies by Baumol,Footnote53 Buelens and Ginsburgh,Footnote54 Frey and Pommerehne,Footnote55 and Pommerehne and Feld.Footnote56 Each of these papers offered important analysis and study design that informed this area of inquiry. Importantly, the clothing and fashion auction data needed for this study was publicly available on Christies.com and was therefore accessible for collection and analysis.

There were clothing auctions discovered on the Christie’s repository that were not used in this study because the clothing was largely historic and included samples of bobbin lace fragments, extant pieces of garments from prior to 1860, and accessories like baby bonnets, hand painted fans, beaded purses, and the like. Similarly, of the auctions that were used in this study it was necessary to go through and manually remove all items that were either not clothing or types of clothing that were beyond the scope of this study. Because the focus of this study was on clothing that has been labelled or “authored”, auction lots without a named designer were not included in the analysis. In this vein, it is important to note that while region or country-specific auctions included clothing unquestionably fundamental within the canons of fashion history, these auctions were not included in this study because of the high propensity to include un-labeled clothing.

Conversely, all instances where the designer or label was suggested but not absolutely certain were included. An example of this includes Lot 106 in Auction 8024 (1998) where the description read: A narrow skirt of cream satin with wide self-coloured band at the hem, possibly Paquin and another similar, the skirt trained. If the auction house included the suggestion, it was decided this information was worth including because the auction house created the allusion to the brand or signifier. References such as “in the style of” a particular designer were not included. All lots of fine jewelry were removed because they were outside the scope of this study and would invariably skew the distribution of pricing information. The data in this study was limited to lots where we could ascertain (at minimum) the label, the type of clothing object, an approximate date of manufacture, and the price.

Remapping the christie’s data

It was necessary to clean and remap the clothing auction data used in this study. Because designers and brands were often referred to interchangeably on Christie’s website, it was necessary to bin these two separate entities under one umbrella term—“label”. This category referred to the designer, brand, fashion house, associated with a given object. There was variability in the depth of information found on Christies’ website; however, the delineation and spelling of brand names was generally consistent. It was nonetheless necessary to remap some of the information in the “Label” category to maintain regularity. The attributes that required the most cleaning and remapping were “Date” (which referred to date of manufacture) and “Category” (which referred to an object’s typology).

Computed dates

For consistency in data analysis, it was necessary to turn all the dates into binned date ranges. Script was written in R to split dates not already binned, into binning conventions. When the date in the raw data was presented as a decade, e.g. the 1950s, it was subsequently binned to 1950-1959 and ultimately represented as 1955.

This same principle applied in cases where there were multiple garments with multiple dates. Because it was impossible to parse out the garments in multiples due to the singular pricing information, they were treated as one entry (or one row in a data table). As such, the date for 3 objects (an example is 1910 | 1920 | 1920) was cleaned to have the date listed as 1915. The original date column which includes multiple dates, ranges, or imprecise century information was retained in the raw data and is available for comparison and further analysis.

Text cues from the “Description” such as “early twentieth century” were factored into the date cleaning process along with more tacit information related to the description of the object(s) and how they may relate to general clothing history, major technological advances in garment construction (for example the advent of the sewing machine ca. 1846), or significant geopolitical events that impacted the textile industry (for example, fabric rations throughout the latter part of World War II). In cases where “nineteenth century” was the only cue, it was again decided to use the middle of the date range as a placeholder, 1850.

Object typology

In cleaning the “category” section of the data it was decided to use general categories to filter all the clothing into umbrella groupings. There was a high degree of inconsistency in how objects were described within and between auctions. As such, it was necessary to bin items under consistent object naming conventions for analysis. In the cases where a lot included multiples, the “category” section was labeled according to the aforementioned general categories and then “multiple” was added.

Currency and inflation

Because most of the auction data collected referred to auctions that took place in London, the currency listed for the “estimated low price”, “estimated high price”, and “hammer prices” were overwhelmingly listed in British Pounds (£) and it was necessary to convert the currency to US Dollars ($). The site macrotrends.net was a helpful resource for logging the pound to dollar exchange rate throughout the course of the last 30+ years. This same information was further adjusted to reflect compound inflation according to the date of the auction. The equation generated from both the exchange and compound inflation rates was applied to all objects within the auction (the lots) and contributed to our understanding of the role of pricing with respect to auction date.

Results and discussion

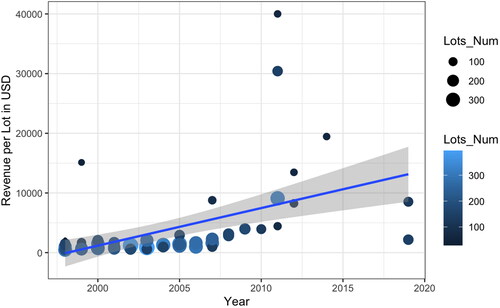

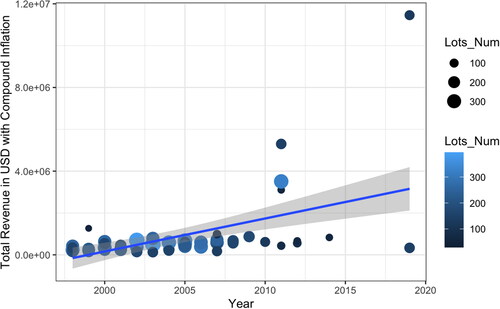

In total the data includes 65 auctions in which 4687 objects were listed at auction between the years 1998 and 2019. Pulling back the lens from the individual objects, the Christie’s data lends itself to assessing the overall revenue of textile and fashion related auctions since 1998. When controlling for inflation, there was a statistically significant positive trend in the revenue of fashion auctions from 1998 to 2019. This was assessed at the aggregate level as well as on a revenue per lot basis. Below are summaries of the raw data as well as the revenue per lot, adjusted for compound inflation, year over year. In the revenue per lot appreciated at a rate of over $600, year over year (p < 0.001), with a highly statistically significant appreciation rate of auction revenue per lot.

Meanwhile, the revenue per lot adjusted for compound inflation in USD showed an appreciation of over $590 year over year with a p-value of .001171. There are many variables affecting the price regression and the multiple r-squared value of .23354 for the revenue per lot adjusted for compound inflation tells us that if we just know year, then we can explain approximately a quarter of the revenue per lot regression model. In considering the import of the multiple r-squared factor, the 23.34% tells us that the progression of time is only one factor affecting appreciation of revenue per lot of luxury fashion items. Because using the variable “year” accounts for 23.34% (unadjusted for compound inflation) this indicates that 75% of the data is explained by other factors and makes a case for moving to multi-level modeling in future studies.

Looking at total auction revenue, the p-value of 8.38e-06 indicates there is a significant appreciation in overall auction revenue year over year, adjusted for compound inflation. The multiple r-squared factor of .2722 indicates that if we only look at year, this one variable accounts for over a quarter of the regression. Overall, auction revenues adjusted for inflation were up on average $147,596 year over year, from 1998 to 2019.

Characterizing the data

In total, there were 20 different attributes (including auction information such as auction title, location, overall revenue, lot pricing estimates, description information, label, dates, etc.) collected for all observed objects listed at auction between 1998 and 2019. Accordingly, each section is characterized below.

Object types

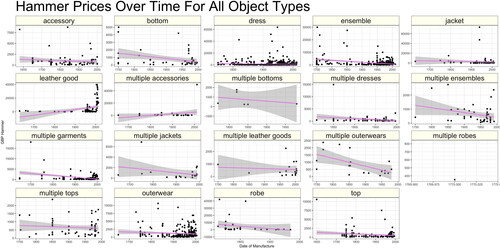

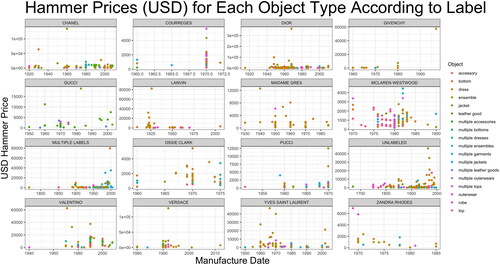

In total there are 19 different object types. Looking more specifically at object types over time, the following pink lines depict the general trends in hammer prices according to the dates the objects were reportedly made.

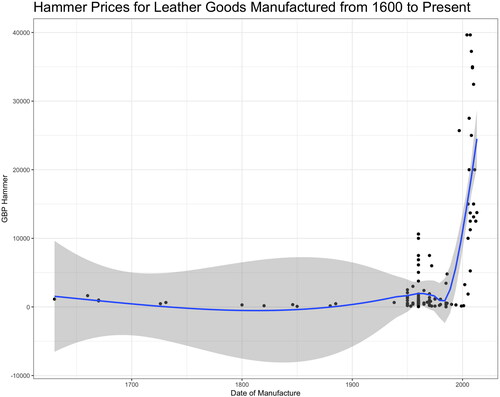

Leather goods are an example of an object type that has a notable positive trend line as the twentieth century progresses. The leather goods here are comprised primarily of handbags and to a lesser degree, luggage.

Based on the data, leather goods have undergone the most significant reclassification of all object types presented in this data. A loess smoother was used to depict the regression more adequately in leather goods. In this case, the line is more nimble and follows the distribution of the price data to depict a notable upward trend. Once created primarily for utilitarian purposes, leather goods—particularly luxury handbags—are important tools in the signification of status. Comparable to sneakers, luxury handbags are part of a robust market for discreet collectible objects, for which supply is often limited. This phenomenon is evinced most notably in the storied waitlist for an Hermès handbag. While handbag and accessory specific auctions were not included in this study, leather goods that were part of larger clothing and fashion auctions are included here. Labels such as Asprey along with vintage Louis Vuitton and Gucci are also well-represented in this data.

Labels

In total, there were 402 different labels observed in all the auctions between 1998-2019. Of the unlabeled objects listed at auction, there were 594 objects that date from before 1900 and 376 that date to the twentieth and/or twenty-first centuries.

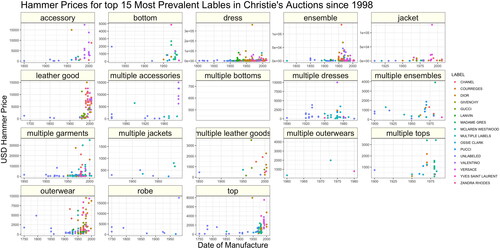

Combining the initial plots of the varying object types found in the data with the information about the top 15 designers, the following trends emerge. The empty plots illustrate the clothing categories that did not overlap with the top 15 labels. The object type categories with the most information were perhaps unsurprisingly, dresses, ensembles, leather goods, multiple garments, outerwear, and to a lesser extent, tops. Perhaps counterintuitively, unlabeled clothing was kept in the list of top 15 labels because the role of unlabeled clothing sold at auction presents some unique avenues of interpreting the data presented here. Notably, in all the plots for which there is enough data to see a trend, the unlabeled garments were primarily found in the date range prior to the 1950s with most unlabeled garments dating to before the 1920s. This trend is consistent with the entrance of many legacy fashion houses in the 1950s that shaped the advent of the contemporary fashion industry today. In many ways the unlabeled data seen here function as an important control group in this study.

Interestingly, the dresses present a clearly delineated decade-by-decade breakdown of trends according to label. The label Lanvin largely characterizes the 1920s, it was the peak of Jeanne Lanvin’s reign at her company prior to the war. Data from the 1930s are notably absent save for a few data points that show some unlabeled dresses as well as those made by Coco Chanel. Dior and Madame Grès appear most prominently in the 1950s. It is difficult to pinpoint one label as standing out more than the others in the 1960s and 1970s. The 1980s and 1990s shows the success of dresses made by Valentino and Versace. The 2000s do not point to one label as standing out in that timeframe.

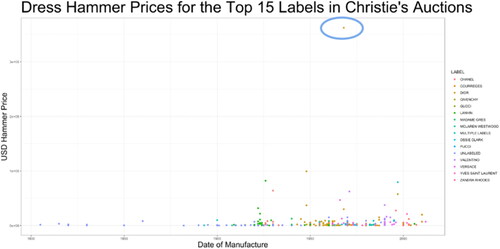

The plot in is a testament to the role of outliers in this analysis. In this instance, the outlier is a silver brocade evening gown designed by Christian Dior and worn by Elizabeth Taylor. Were it not for this garment (and several other garments owned by Elizabeth Taylor that also brought in hammer prices well over six figures) most dresses would have hammer prices less than $50K. This is a testament to not only to the price premium associated with celebrity ownership but also to the price premium associated specifically with Elizabeth Taylor.

Figure 5 Hammer prices for the top 15 most prevalent labels listed at auction at Christies since 1998, organized according to object type.

Figure 6 Dress hammer prices for the top 15 most prevalent labels listed at auction at Christies. The figure depicts the presence of outliers in the data.

Viewed another way, the plots below are organized by label and then facetted according to object type, and a more comprehensive picture of each label’s representation in the Christies’ data is demonstrable. Again, the figure below represents the 15 most prevalent labels.

Labels like Madame Grès were represented almost exclusively in dresses. This is consistent with her focus on elaborate, draped Grecian gowns. While Madame Grès began her first couture house in the 1930s, her career was interrupted by the war in Europe, and she gained the most acclaim in the 1950s and 1960s. As a designer with a distinct signature dressmaking style defined by masterful draping, elaborate pleating, and the use of diaphanous fabrics, her signature look did not change dramatically from decade to decade. Additionally, she remained at the helm of her company for the duration of the timeframe presented in the plot. This is one potential reason the data suggests the hammer prices for her dresses did not change significantly between 1950 and 1970.

Looking specifically at the higher price points for each brand, there are peaks for 1920s Lanvin, 1970s Courrèges, 1950s Dior, 1960s Yves Saint Laurent. In each of these cases, the market seems to indicate a willingness to pay more for masthead era clothing, or the period in which the named designer was the head of their eponymously named fashion house. While perhaps intuitive, the observance of this phenomenon is an important finding of this research. The labels “Versace” and “Paco Rabanne” are just two examples where the lots consistently performed well above the estimated high price.

Specific auctions

Turning the lens specifically to Christie’s auction number 5286, titled twentieth Century Fashion which took place in November of 2007, the hammer prices were consistently on the low end of the estimated value or below the range entirely. In this one auction, Yves Saint Laurent, Fendi, Issey Miyake, Claude Montana, Emanuel Ungaro, and Loewe consistently performed below the estimated sale range. Exceptions to this trend were Halston, Dior Couture, and lots that had significant provenance, discussed at more length below. There were multiple examples of individual lots with clothing designed by Azzedine Alaïa, Pierre Cardin, or Christian Dior that performed well above their estimated ranges and these examples presented unique scenarios for analysis.

In general, the hammer price for clothing designed by Azzedine Alaïa was below the estimated low value however, an “Unstructured Suit” (Lot 170) designed by Alaïa sold for £2,250 or 450% over the estimate high price. Other examples of a similar magnitude of upward bound price discrepancy are seen in Lot 152, a 1968 Pierre Cardin black tunic mini-dress with silver metal plates (500% over the estimated high price), which is also emblematic of Cardin’s 1960s era modern silhouette. Lot 93, a Dior 1952 ensemble that is archetypal of Dior’s “New Look” silhouette which, defined an era (almost 300% over estimated high price). By 2023 standards, auction number 5286 included many notable garments from fashion history though only a small handful of lots received a comparable level of interest and investment in the mid-2000s.

Provenance

Provenance is an important component of an object’s significance in museological contexts as well as cultural economics. While provenance often refers to a record of ownership, it is interpreted in this context to refer more broadly to the factors affecting authentication of an object. Again, from the 2007 Christie’s auction numbered 5286, twentieth Century Fashion, provenance plays an important role in examining the determinants of a price premium. In the following two examples from Auction 5286, the objects from the auction were compared to more contemporary sales to illustrate the changing monetary value associated with authentic clothing from eminent fashion eras and creative directors.

One notable example is Lot 196 which featured a gentlemen’s frock coat designed by John Galliano which sold for £1,750, 350% the highest estimate, presumably because the coat was acquired at Galliano’s 1984 Central St. Martin’s “Les Incroyables” student show. The estimated low price was £300, the estimated high price was £500, and it ultimately sold for £1,750. The jacket was an oversized coat reminiscent of a nineteenth century men’s frock coat. A separate coat from the same 1984 “Les Incroyables” collection later sold at auction at the renowned fashion auctioneer Kerry Taylor Auctions in June of 2019 for £65,000.Footnote57

Visually, these two coats are different yet, if compared as similar rare object types, the rate of return for investing in an early Galliano coat from’ Les Incroyables’ shows a price appreciation of over 2600%. The Galliano coat that sold in 2007 for £1750, adjusted for compound inflation (2.8% according to the Bank of England Inflation Calculator) until 2019 would put the coat at a cost of £2,446.35. This leaves a £62,553.65 price premium in 2019 that is a testament to the shift in value placed on older, increasingly rare fashion objects. Yet another jacket from the “Les Incroyables” collection was sold to Diana Ross and remains privately held.Footnote58

Continuing in this vein, lots 213-224 featured selections from Vivienne Westwood’s earliest fashion shows including Pirate, Savage, Nostalgia of Mud, Punkature and Witches. The lots similarly date to the early to mid-1980s and were important collections in the canons of fashion history. In these nine lots, the average hammer price was approximately £853 and the estimated price range was listed between £400 on the low end and £700 on the high end. There were three of the nine lots that sold for less than the estimated low price so the average price was pulled up by several lots which drew more than £1,000 to £2,500. Each lot included multiple garments in the Christie’s sale

Limitations

The granularity of the detail discussed throughout this section, particularly with respect to the data remapping process is intended to offer future users of the dataset other avenues by which to sort and subsequently analyze the data. Other approaches to naming conventions or different ways of collapsing the distinction between designers and brands would potentially change the findings of this study. One example would be the ways in which large date ranges were collapsed into century or decade midpoints. The combination of date-specific information from the luxury fashion industry—when a fashion house was founded and the dates of tenure of the biggest designers—could in theory be used to further coalesce important information relating to significant eras of design at the varying brands/labels. The same could be said of the ways in which object types were collated into larger umbrella groups.

Conclusion

The findings of this study underscore the hypothesis that fashion auctions of named, luxury clothing from the canons of fashion history have become increasingly lucrative in the twenty first century as the historical provenance of clothing becomes increasingly salient in contemporary markets. Looking specifically at dresses according to different fashion houses, the data suggests there is a masthead era designer effect where clothing designed by the founder and named designer of the house is more expensive when sold at auction. This is seen most notably when the clothing features hallmarks design elements or a signature silhouette emblematic of the designer, era, and fashion house (e.g. Dior’s new look silhouette or Valentino Red).

Fashion auctions in general, as a proxy for the online auction of high-end luxury clothing, have appreciated in overall revenue generation. Moreover, the results of this study shed light on the process of valorization by which designed objects like clothing become collectible assets. At the heart of this study are issues that are inherently speculative and teleological. Is an exploratory study about the investment value of clothing sold at auction in the twenty first century the next logical step in contemporary capitalism? Or, as clothing has become increasingly devalued in the twenty first century, is an empirical study about the investment value of clothing an opportunity to reinscribe value to clothing? In the end, this study does not answer either these questions. What this study does say, I hope rather explicitly, is that if fashion is art, then perhaps it should be valued as such.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Katherine Greder

Katherine Greder is an Assistant Professor of Design Studies in the Department of Media Arts, Design and Technology at North Carolina State University. Her research focuses on the circular economy and assetization as a mechanism for exploring the alignment of financial incentives for decarbonization in the global fashion system. Kate holds a PhD from the Department of Human Centered Design at Cornell University. [email protected]

Stephen Parry

Stephen Parry is a statistician at Cornell’s Statistical Consulting Unit. Stephen collaborates on a wide range of research projects and has published in a diverse range of fields including, but not limited to, agriculture, veterinary medicine, sociology, design, psychology, and linguistics. He was awarded an Ig Nobel in Transportation in 2021 and co-authored a manuscript on Best Practices on Collecting Gender and Sex Data in 2022. Stephen has a M.S. in Statistics from Syracuse University. [email protected]

Van Dyk Lewis

Van Dyk Lewis is an Associate Professor in the Department of Human Centered Design at Cornell University. Van Dyk’s research touches on design criticism, fashion theory, alternative fashion futures, and critical luxury studies. Van Dyk holds a PhD in Cultural Studies from the University of Birmingham in England. [email protected]

Notes

1 Kim, Sung Bok. “Is Fashion Art?” Fashion Theory 2, no. 1 (1998): 51–71. https://doi.org/10.2752/136270498779754515.

2 Menkes, Suzy. “Fashion as Art.”Art Review (2003).

3 Wilson, Elizabeth. 2003. Adorned in Dreams: Fashion and Modernity. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

4 Horkheimer, Max, and Theodor Adorno. 2002. “Dialectic of Enlightenment : Philosophical Fragments.” In Cultural Memory in the Present. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. https://catalog.lib.ncsu.edu/catalog/NCSU1554941

5 Miller, Sanda. “Fashion as Art; is Fashion Art?” Fashion Theory 11, no. 1 (2007): 25–40. https://doi.org/10.2752/136270407779934551.

6 Muniesa, Fabian, and Kean Birch, eds. 2020. “Assetization : Turning Things into Assets in Technoscientific Capitalism.” In Inside Technology. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. https://catalog.lib.ncsu.edu/catalog/NCSU5022870

7 Muniesa, Fabian, and Kean Birch, eds. 2020. “Assetization : Turning Things into Assets in Technoscientific Capitalism.” In Inside Technology. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. https://catalog.lib.ncsu.edu/catalog/NCSU5022870

8 Kawamura, Yuniya. 2005. Fashion-Ology: An Introduction to Fashion Studies. eBook. Dress, Body, Culture. London, England: Bloomsbury Academic.

9 Vasari, Giorgio. 2006. The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects. Edited by Philip Jacks. Translated by Gaston du C. de Vere. Modern Library.

10 Frick, Carole Collier. 2005. “The Florentine Rigattieri: Secondhand Clothing Dealers and the Circulation of Goods in the Renaissance.” In Old Clothes, New Looks, edited by Alexandra Palmer and Hazel Clark, 13–28. New York, NY: Berg Publishers.

11 Allerston, Patricia. “Reconstructing the Second-Hand Clothes Trade in Sixteenth and Seventeenth-Century Venice.” Costume 33, no. 1 (1999): 46–56.

12 Ginsburg, Madeline. “Rags to Riches: The Second-Hand Clothes Trade 1700-1978.” Costume 14, no. 1 (1980): 121–135.

13 McNeil, Peter. 2010. “Fashion Designers.” In Berg Encyclopedia of World Dress and Fashion: West Europe, edited by Lise Skov, 129–136. Oxford: Berg.

14 Ribeiro, Aileen. 2002. Dress in Eighteenth-Century Europe 1717-1789. 2nd ed. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

15 Ribeiro, Aileen. 2002. Dress in Eighteenth-Century Europe 1717-1789. 2nd ed. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

16 Roche, Daniel. 1994. The Culture of Clothing: Dress and Fashion in the Ancien Regime. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

17 Ribeiro, Aileen. 2002. Dress in Eighteenth-Century Europe 1717-1789. 2nd ed. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

18 McNeil, Peter. 2010. “Fashion Designers.” In Berg Encyclopedia of World Dress and Fashion: West Europe, edited by Lise Skov, 129–136. Oxford: Berg.

19 Trubert-Tollu, Chantal, Françoise Tétart-Vittu, et al., 2017. The House of Worth 1858-1954: The Birth of Haute Couture. London: Thames & Hudson.

20 Trubert-Tollu, Chantal, Françoise Tétart-Vittu, et al., 2017. The House of Worth 1858-1954: The Birth of Haute Couture. London: Thames & Hudson.

21 Musée des arts décoratifs. 2017. Fashion Forward: 300 Years of Fashion: Collections of the Musee Des Arts Decoratifs, Paris. New York: Rizzoli.

22 Trubert-Tollu, Chantal, Françoise Tétart-Vittu, et al., 2017. The House of Worth 1858-1954: The Birth of Haute Couture. London: Thames & Hudson.

23 Berry, Jess. 2018. “Introduction: The House of Fashion.” In Haute Couture and the Modern Interior, 1–8. London, England: Bloomsbury Visual Arts, Bloomsbury Fashion Central.

24 McLoughlin, Marie. “Fashion Education in London in the 20s and 30s and the Legacy of Muriel Pemberton.” Apparence(s) 7, no. 7 (2017). http://journals.openedition.org/apparences/1372

25 McLoughlin, Marie. “Fashion Education in London in the 20s and 30s and the Legacy of Muriel Pemberton.” Apparence(s) 7, no. 7 (2017). http://journals.openedition.org/apparences/1372

26 McLoughlin, Marie. “Fashion Education in London in the 20s and 30s and the Legacy of Muriel Pemberton.” Apparence(s) 7, no. 7 (2017). http://journals.openedition.org/apparences/1372

27 Hegland, Jane. 2010. “Dress and Fashion Education: Design and Business.” In Berg Encyclopedia of World Dress and Fashion: Global Perspectives, edited by Joanne B. Eicher and Phyllis G. Tortora, 311–318. Oxford: Berg.

28 McNeil, Peter. 2010. “Fashion Designers.” In Berg Encyclopedia of World Dress and Fashion: West Europe, edited by Lise Skov, 129–136. Oxford: Berg.

29 Steele, Valerie. “Museum Quality: The Rise of the Fashion Exhibition.” Fashion Theory 12, no. 1 (2008): 7–30. https://doi.org/10.2752/175174108X268127.

30 Anderson, Fiona. 2000. “Museums as Fashion Media.” In Fashion Cultures: Theories, Explorations and Analysis, edited by Stella Bruzzi and Pamela Church. Gibson. London: Routledge.

31 Stoppard, Lou. “Bringing the Fashion Exhibition to Life.” Financial Times (2016).

32 Melchior, Marie Riegels, and Birgitta Svensson, eds. 2014. Fashion and Museums: Theory and Practice. New York: Bloomsbury USA.

33 Wallenberg, Louise. “Art, Life, and the Fashion Museum: For a More Solidarian Exhibition Practice.” Fashion and Textiles 7, no. 1 (2020): 17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40691-019-0201-5.

34 Pecorari, Marco. “Fashion Archives, Museums and Collections in the Age of the Digital.” Critical Studies in Fashion & Beauty 10, no. 1 (2019): 3–29. https://doi.org/10.1386/csfb.10.1.3_7.

35 Franceschini, Marta. “Navigating Fashion: On the Role of Digital Fashion Archives in the Preservation, Classification and Dissemination of Fashion Heritage.” Critical Studies in Fashion & Beauty 10, no. 1 (2019): 69–90. https://doi.org/10.1386/csfb.10.1.69_1.

36 Evans, Caroline. 2013. The Mechanical Smile: Modernism and the First Fashion Shows in France and America, 1900-1920. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

37 Evans, Caroline. 2013. The Mechanical Smile: Modernism and the First Fashion Shows in France and America, 1900-1920. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

38 Luther, Marylou. 2010. “Fashion Journalism.” In The Berg Companion to Fashion, edited by Valerie Steele, 293–296. Oxford, UK: Bloomsbury Academic.

39 Luther, Marylou. 2010. “Fashion Journalism.” In The Berg Companion to Fashion, edited by Valerie Steele, 293–296. Oxford, UK: Bloomsbury Academic.

40 Armitage, John. 2020. Luxury and Visual Culture. London, England: Bloomsbury Visual Arts.

41 Palmer, Alexandra. 2001. Couture & Commerce: The Transatlantic Fashion Trade in the 1950s. Vancouver, BC: UBC Press.

42 Palmer, Alexandra. 2001. Couture & Commerce: The Transatlantic Fashion Trade in the 1950s. Vancouver, BC: UBC Press.

43 Palmer, Alexandra. 2001. Couture & Commerce: The Transatlantic Fashion Trade in the 1950s. Vancouver, BC: UBC Press.

44 Lake, Stephanie. 2010. “Dress and the Art Trade.” In Berg Encyclopedia of World Dress and Fashion, 133–35. Global Perspectives. Oxford: Berg.

45 Lake, Stephanie. 2010. “Dress and the Art Trade.” In Berg Encyclopedia of World Dress and Fashion, 133–35. Global Perspectives. Oxford: Berg.

46 Schiro, Anne-Marie. 1997. “Giving Haute Couture Auction Cachet.” The New York Times, August 26, 1997. Gale Academic OneFile. http://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A150299130/AONE?u=cornell&sid=zotero&xid=f057d0f6

47 D’Amato, Jenny. “Frock Options: Haute Couture or Vintage Ready-to-Wear—Auction Houses Are Profiting from Runway Inflation.” Art & Auction (1998).

48 Bumiller, Elisabeth. 1997. “Diana Cleans Out Her Closet, And Charities Just Clean Up.” The New York Times, June 26, 1997, sec. New York. https://www.nytimes.com/1997/06/26/nyregion/diana-cleans-out-her-closet-and-charities-just-clean-up.html

49 Lake, Stephanie. 2010. “Dress and the Art Trade.” In Berg Encyclopedia of World Dress and Fashion, 133–35. Global Perspectives. Oxford: Berg.

50 Schiro, Anne-Marie. 1997. “Giving Haute Couture Auction Cachet.” The New York Times, August 26, 1997. Gale Academic OneFile. http://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A150299130/AONE?u=cornell&sid=zotero&xid=f057d0f6

51 Lake, Stephanie. 2010. “Dress and the Art Trade.” In Berg Encyclopedia of World Dress and Fashion, 133–35. Global Perspectives. Oxford: Berg.

52 Reitlinger, Gerald. 1964. The Economics of Taste. Vol. 1. London, England: Barrie and Rockliff.

53 Baumol, William J. “Unnatural Value: Or Art Investment as Floating Crap Game.” The American Economic Review 76, no. 2 (1986): 10.

54 Buelens, Nathalie, and Victor Ginsburgh. “Revisiting Baumol’s ‘Art as Floating Crap Game.” European Economic Review 37, no. 7 (1993): 1351–1371.

55 Frey, Bruno, and Werner Pommerehne. “Art Investment: An Empirical Inquiry.” Southern Economic Journal 56, no. 2 (1989): 396.

56 Pommerehne, Werner, and Lars Feld. “The Impact of Museum Purchase on the Auction Prices of Paintings on JSTOR.” Journal of Cultural Economics 21, no. 3 (1997): 249–271.

57 Taylor, Kerry. 2021. “Lot 153 - An Important John Galliano ‘Les Incroyables’ Coat.” https://www.kerrytaylorauctions.com/auction/lot/153-an-important-john-galliano-les-incroyables/?lot=1405&sd=1

58 Taylor, Kerry. 2021. “Lot 153 - An Important John Galliano ‘Les Incroyables’ Coat.” https://www.kerrytaylorauctions.com/auction/lot/153-an-important-john-galliano-les-incroyables/?lot=1405&sd=1

Bibliography

- Allerston, Patricia. “Reconstructing the Second-Hand Clothes Trade in Sixteenth and Seventeenth-Century Venice.” Costume 33, no. 1 (1999): 46–56. doi:10.1179/cos.1999.33.1.46.

- Anderson, Fiona. 2000. “Museums as Fashion Media.” In Fashion Cultures: Theories, Explorations and Analysis, edited by Stella Bruzzi and Pamela Church. Gibson. London: Routledge.

- Armitage, John. 2020. Luxury and Visual Culture. London, England: Bloomsbury Visual Arts.

- Baumol, William J. “Unnatural Value: Or Art Investment as Floating Crap Game.” The American Economic Review 76, no. 2 (1986): 10.

- Berry, Jess. 2018. “Introduction: The House of Fashion.” In Haute Couture and the Modern Interior, 1–8. London, England: Bloomsbury Visual Arts, Bloomsbury Fashion Central.

- Buelens, Nathalie, and Victor Ginsburgh. “Revisiting Baumol’s ‘Art as Floating Crap Game.” European Economic Review 37, no. 7 (1993): 1351–1371. doi:10.1016/0014-2921(93)90060-N.

- Bumiller, Elisabeth. 1997. “Diana Cleans Out Her Closet, And Charities Just Clean Up.” The New York Times, June 26, 1997, sec. New York. https://www.nytimes.com/1997/06/26/nyregion/diana-cleans-out-her-closet-and-charities-just-clean-up.html

- D’Amato, Jenny. “Frock Options: Haute Couture or Vintage Ready-to-Wear—Auction Houses Are Profiting from Runway Inflation.” Art & Auction (1998): 82–87.

- Evans, Caroline. 2013. The Mechanical Smile: Modernism and the First Fashion Shows in France and America, 1900-1920. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Franceschini, Marta. “Navigating Fashion: On the Role of Digital Fashion Archives in the Preservation, Classification and Dissemination of Fashion Heritage.” Critical Studies in Fashion & Beauty 10, no. 1 (2019): 69–90. doi:10.1386/csfb.10.1.69_1.

- Frey, Bruno, and Werner Pommerehne. “Art Investment: An Empirical Inquiry.” Southern Economic Journal 56, no. 2 (1989): 396. doi:10.2307/1059218.

- Frick, Carole Collier. 2005. “The Florentine Rigattieri: Secondhand Clothing Dealers and the Circulation of Goods in the Renaissance.” In Old Clothes, New Looks, edited by Alexandra Palmer and Hazel Clark, 13–28. New York, NY: Berg Publishers.

- Ginsburg, Madeline. “Rags to Riches: The Second-Hand Clothes Trade 1700-1978.” Costume 14, no. 1 (1980): 121–135. doi:10.1179/cos.1980.14.1.121.

- Hegland, Jane. 2010. “Dress and Fashion Education: Design and Business.” In Berg Encyclopedia of World Dress and Fashion: Global Perspectives, edited by Joanne B. Eicher and Phyllis G. Tortora, 311–318. Oxford: Berg.

- Horkheimer, Max, and Theodor Adorno. 2002. “Dialectic of Enlightenment : Philosophical Fragments.” In Cultural Memory in the Present. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. https://catalog.lib.ncsu.edu/catalog/NCSU1554941

- Kawamura, Yuniya. 2005. Fashion-Ology: An Introduction to Fashion Studies. eBook. Dress, Body, Culture. London, England: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Kim, Sung Bok. “Is Fashion Art?”Fashion Theory 2, no. 1 (1998): 51–71. doi:10.2752/136270498779754515.

- Lake, Stephanie. 2010. “Dress and the Art Trade.” In Berg Encyclopedia of World Dress and Fashion, 133–35. Global Perspectives. Oxford: Berg.

- Luther, Marylou. 2010. “Fashion Journalism.” In The Berg Companion to Fashion, edited by Valerie Steele, 293–296. Oxford, UK: Bloomsbury Academic.

- McLoughlin, Marie. “Fashion Education in London in the 20s and 30s and the Legacy of Muriel Pemberton.” Apparence(s) 7, no. 7 (2017): 2. http://journals.openedition.org/apparences/1372 doi:10.4000/apparences.1372.

- McNeil, Peter. 2010. “Fashion Designers.” In Berg Encyclopedia of World Dress and Fashion: West Europe, edited by Lise Skov, 129–136. Oxford: Berg.

- Melchior, Marie Riegels, and Birgitta Svensson, eds. 2014. Fashion and Museums: Theory and Practice. New York: Bloomsbury USA.

- Menkes, Suzy. “Fashion as Art.” Art Review (2003): 44–49.

- Miller, Sanda. “Fashion as Art; is Fashion Art?”Fashion Theory 11, no. 1 (2007): 25–40. doi:10.2752/136270407779934551.

- Muniesa, Fabian, and Kean Birch, eds. 2020. “Assetization : Turning Things into Assets in Technoscientific Capitalism.” Inside technology. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. https://catalog.lib.ncsu.edu/catalog/NCSU5022870

- Musée des arts décoratifs. 2017. Fashion Forward: 300 Years of Fashion: Collections of the Musee Des Arts Decoratifs, Paris. New York: Rizzoli.

- Palmer, Alexandra. 2001. Couture & Commerce: The Transatlantic Fashion Trade in the 1950s. Vancouver, BC: UBC Press.

- Pecorari, Marco. “Fashion Archives, Museums and Collections in the Age of the Digital.” Critical Studies in Fashion & Beauty 10, no. 1 (2019): 3–29. doi:10.1386/csfb.10.1.3_7.

- Pommerehne, Werner, and Lars Feld. “The Impact of Museum Purchase on the Auction Prices of Paintings on JSTOR.” Journal of Cultural Economics 21, no. 3 (1997): 249–271. doi:10.1023/A:1007388024711.

- Reitlinger, Gerald. 1964. The Economics of Taste. Vol. 1. London, England: Barrie and Rockliff.

- Ribeiro, Aileen. 2002. Dress in Eighteenth-Century Europe 1717-1789. 2nd ed. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Roche, Daniel. 1994. The culture of clothing: Dress and fashion in the ancien regime. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Schiro, Anne-Marie. 1997. “Giving Haute Couture Auction Cachet.” The New York Times, August 26, 1997. Gale Academic OneFile. http://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A150299130/AONE?u=cornell&sid=zotero&xid=f057d0f6

- Steele, Valerie. “Museum Quality: The Rise of the Fashion Exhibition.” Fashion Theory 12, no. 1 (2008): 7–30. doi:10.2752/175174108X268127.

- Stoppard, Lou. “Bringing the Fashion Exhibition to Life.” Financial Times (2016).

- Taylor, Kerry. 2021. “Lot 153 - An Important John Galliano ‘Les Incroyables’ Coat.” https://www.kerrytaylorauctions.com/auction/lot/153-an-important-john-galliano-les-incroyables/?lot=1405&sd=1

- Trubert-Tollu, Chantal, Françoise Tétart-Vittu, Jean-Marie Martin-Hattemberg, and Fabrice Olivieri. 2017. The House of Worth 1858-1954: The Birth of Haute Couture. London: Thames & Hudson.

- Vasari, Giorgio. 2006. The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects. Edited by Philip Jacks. Translated by Gaston du C. de Vere. New York, N.Y.: Modern Library.

- Wallenberg, Louise. “Art, Life, and the Fashion Museum: For a More Solidarian Exhibition Practice.” Fashion and Textiles 7, no. 1 (2020): 17. doi:10.1186/s40691-019-0201-5.

- Wilson, Elizabeth. 2003. Adorned in Dreams: Fashion and Modernity. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.