ABSTRACT

Community engagement programmes are increasingly designed into archaeological projects in Sudan, largely prompted by the remit and funding of the Qatar-Sudan Archaeological Project (QSAP; 2013-present). This paper provides a critical reflection on how a British Museum project in northern Sudan instigated, evaluated and modified its community programme across twelve years, before, during and after QSAP funding. We outline the transition from western institutional project design and information sharing, to enhanced collaboration and local agency, within the context of specific local understandings of heritage (turath). The case study highlights the challenges, opportunities and some possible methodologies for archaeology projects within post-colonial environments.

Local communities, until recently, have rarely been included in the practice of researching the history and archaeology of Sudan (Näser and Tully Citation2019). Rather, projects have generally been designed by professional archaeologists, historians and Egyptologists to reflect their research interests, or responded to threats from infrastructural developments, such as road or dam projects (Kleinitz and Näser Citation2013). Though employing local workers and interacting with communities in a number of other ways, these researchers rarely explored or understood the spectrum of community relationships with archaeological heritage, which can range from attachment and association to a sense of alienation. Whilst the emergence of ethno-archaeological research in the Nile Valley led to richer research-led interactions with communities, local perspectives on the ancient, region-specific, past were generally not considered: most international and Sudanese archaeologists study the past in isolation from modern communities, placing local communities in the role of passive consumers of information (Humphris, Bradshaw, and Emberling Citation2021). Community involvement is further denied through the current governmental and disciplinary framework for archaeological heritage, which remains shaped by the era of Anglo-Egyptian rule (1898–1956) in Sudan (see Näser Citation2021). The national laws pertaining to archaeological remains, alongside their management and administration which fall under the responsibility of the National Corporation for Antiquities & Museums (NCAM), largely reflect those introduced under colonialism, which included the creation of NCAM’s predecessor, the Sudan Antiquities Service, in 1903 (see Fushiya Citation2020, 64–75, 126–8).

The launch of the Qatar-Sudan Archaeological Project (QSAP) in 2013, a major bilateral fund that supported 42 archaeological projects from 25 institutions – international and Sudanese – to deliver research, site protection and public engagement, provided an opportunity for a change in how archaeologists and community interacted. This paper focuses on one site – Amara West/Abkanisa in northern Sudan – and its nearby communities. Authored by five members of the British Museum Amara West Research Project team, it offers a critical reflection upon local community engagement initiatives across twelve field seasons (2008–2019). Incorporating survey and evaluation data, the paper signals opportunities for future community archaeologies in Sudan.

Amara West: research project design and outputs

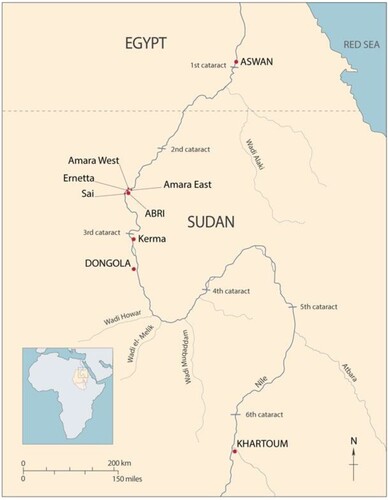

Located 720 km north of Khartoum, the site designated Amara West by archaeologists () is known as Abkanisa to the local community. The latter toponym reflects the wider phenomenon of designating pre-Islamic monuments with kanisa, the Arabic term for church (Fushiya Citation2020, 155). Founded around 1300 BCE, Amara West/Abkanisa provided a new centre for the colonial administration of Upper Nubia, ruled by pharaonic Egypt between around 1500 and 1070 BCE. The British Museum’s Amara West Research Project sought to explore lived experience in this ancient colonial and urban setting, within the framework of cultural entanglement, using a range of interdisciplinary methodologies to research foodways, technologies, health, social structures and funerary beliefs (Binder Citation2017; Fulcher Citation2022; N. Spencer Citation2015; Citation2017; Woodward et al. Citation2017).

Community engagement was absent from the original project scope, conceived at the British Museum in 2008. Local communities were not consulted: NCAM provided the fieldwork permit for the archaeological concession but were not involved in research design. An international team of archaeologists, environmental scientists, cultural anthropologists and bioarchaeologists convened for twelve annual winter field seasons, living in a house on Ernetta island. Few spoke Arabic, the national language of Sudan, and none spoke the local language of the area, Nobiin. Two inspectors assigned by NCAM were integral parts of the project and its research: co-authors Abd Rabo (a curator in the Sudan National Museum) and Saad (bioarchaeologist). In line with regulation and historic practice by archaeological missions in Sudan, a local workforce was recruited to undertake archaeological labour, comprising farmers but also policemen, nurses and the occasional archaeology graduate. These were recruited by the NCAM site guard (ghaffir), resulting in an injection of cash into the local economy economically. The archaeological wages were set by the project director in consultation with the ghaffir and inspectors; it has been noted elsewhere that rates rarely keep up with inflation (Bradshaw Citation2018). Other project employees included a house assistant and cook. These Sudanese team members and employees, with their different perspectives, would significantly shape our approach to community engagement.

The research team authored print and online publications from 2009 onwards, targeted at academic audiences.Footnote1 Engagement with wider audiences was considered from the outset, unsurprisingly given the project was conceived within a national public museum, but a project blogFootnote2 and social media postsFootnote3 from the fieldwork and post-excavation were written in English and largely read by European and North American audiences (on the basis of analytics generated by the British Museum Web Team). These included content by individual team members on day-to-day life on fieldwork, and the modern context of working in a living community.

Communities around Amara West

No communities live in the immediate vicinity of the archaeological site, set in an arid desert environment not suitable for dwelling or agriculture, and difficult to access due to the large riverside sand-dunes and lack of roads. Few visitors, whether local, tourists or archaeologists, come to Amara West, as the ancient remains are largely buried or unintelligible.

We chose three nearby communities for community engagement. Firstly Abri, a town of 4000 inhabitants (in 2015) that was developed as an administrative centre by the British colonial government in 1921, located 5.5 km upstream of Amara West, on the opposite bank. Comprising a market, banks, police station and regional court, a hospital, and both primary and secondary schools, the town provided the Project with food and other services (blacksmith, carpenter, equipment repair, fuel). Secondly, we engaged with Amara [East], a village of around 1000 inhabitants, 5 km east of Abri. This village hosted the project house, and provided workmen, for British-led excavations (Egypt Exploration Society [EES]) in the 1930s and 1940s (Fairman Citation1990); it was the toponym of this village that was applied by archaeologists to the ancient site across the river. Thirdly, we focused on the 4km-long island of Ernetta opposite Abri, which is home to several hundred inhabitants living in traditional mud-brick and rammed mud (jalous) houses set amidst date palm-groves and small-scale agricultural plots (Ryan et al. Citation2022). As the location for the Project house from 2008, and home to most of the hired workforce, Ernetta witnessed the most sustained engagement between archaeologists and communities. These places do of course comprise multiple communities, with complex and overlapping identities and including an array of genders, ages, occupations, backgrounds (educational, ethnic, cultural) and economic circumstances (Marshall Citation2002; Smith and Waterton Citation2009). Furthermore, as economic and educational migration is widespread in Sudan, those who have left continue to exert socio-economic influence and contribute to community experiences, knowledge and perspectives (Willemse Citation2017).

People in all three communities had prior awareness of the archaeological site and project, considered part of local Nubian heritage (turath) and history. Turath, as used by these communities, encompasses a fluid set of components, including but not limited to language, landscape, agricultural practice, faith and passage of life rituals, social relations, foodways, material culture and archaeological remains and music. In addition, turath incorporated oral traditions, including legendary stories and memories of past excavations passed down through generations. Turath is dynamic and changing, constructed dialogically through social interactions, meaning-making and value attributions, by both individuals and groups (Byrne Citation2008; Harrison Citation2013, 4).

Programmes and impact at Amara West

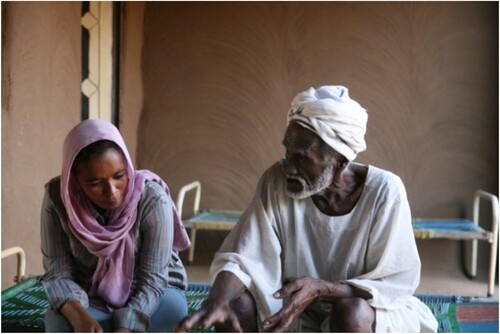

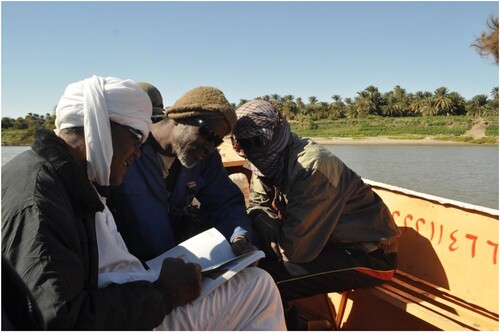

Community engagement can comprise consultation, interviews, activities, planning and decision-making about the engagement, and, in a more informal way, various forms of communications and interactions for, and between, different groups of peoples (Thomas, McDavid, and Gutteridge Citation2014). Initially, Abd Rabo shared archaeological results with the local community through informal conversations, which led to Spencer and Abd Rabo interviewing residents of Amara East and Ernetta who had been workmen in the EES excavations (), complemented by site visits and the sharing of EES archival photographs (Abd Rabo and Spencer Citation2014; Fushiya Citation2017; Fushiya Citation2020, 136–153). This initiative was envisaged as providing a balance to European archives and memories of the excavations at the site (see P. Spencer Citation1997; Citation2002; Citation2016). The interviews revealed memories of employment within the EES project, led by British archaeologists directing Egyptian workmen, who acted as (sometimes violent) foremen (rayis) overseeing Sudanese labour: the macrocosm of the Anglo-Egyptian colonial project applied within a cultural heritage microcosm.

From 2014, the stipulations of QSAP funding prompted a scaling up and reconsideration of community engagement. Each project had to produce a booklet or leaflet in English and Arabic and, where appropriate, create a site museum or information point. Neither QSAP nor NCAM provided guidelines or regulations for such outputs, which led to variation of design and approach. This flexibility did allow directors and other team members of individual fieldwork projects, their NCAM representatives and (less frequently) communities to tailor outputs to the needs and interests of audiences local to the sites, in light of the perceived importance of the place, or indeed the perceptions of archaeologists as to what communities wanted.Footnote4 QSAP funding, complemented by other grants (see below), would sustain community engagement at Amara West through until the last fieldwork season in 2019.

Broadcast programmes

Fushiya was appointed to lead community-focused activities at Amara West, conceived by the project team as information sharing with the local communities: programmes were delivered in ‘broadcast’ mode, characterized by one-way communication, inevitably not always reflecting the local communities’ interests and needs (McManamon Citation2000; Pyburn Citation2011). The engagement was not collaborative, nor research-led, with no formal consultation with the local communities during content development and programme design. This was in keeping with the majority of archaeological practice in the Nile Valley up to the late 2000s, including that of other British Museum projects. Continuing the theme of foreign agency, a QSAP requirement for a museum or information point prompted the Project to conceive, design and commission construction of a visitor orientation space in February 2014, with seven bilingual information panels mounted in the shaded verandah in early 2015. Authored by Spencer with input from Fushiya, Abdo Rabo and Michaela Binder, the team’s bioarchaeologist, these provided a history of (European) exploration of the site, the key features of Amara West and information on food, health and evidence for Nubian culture. Those thematic subjects were selected as informal discussions with workmen and their families revealed them to be of particular interest to local communities. A series of free podcasts, narrated by Abd Rabo (Arabic) and Spencer (English), provided a further channel for circulating the information, and presentations and discussions were scheduled in the Ernetta club (nadi), and a room within the Abri Administrative Unit, delivered by Spencer, Fushiya, Saad, Abd Rabo, Binder and ceramicist Anna Garnett. Site tours were organized for local primary school groups in 2015, 2016 and 2018, led by Fushiya, Saad, the project bioarchaeologist and two local excavation workers.

The other deliverable stipulated by QSAP, a book for local communities, was authored by several project team members. This 114-page publication was printed in Arabic and English editions (Spencer, Stevens, and Binder Citation2014). Chapters on the historical and cultural context, the history of research and the results of fieldwork were combined with ‘focus spreads’ on specific object groups and themes. It was a thoroughly enjoyable book for the archaeological team to write, providing an accessible synthesis of a type that archaeological projects rarely have the impetus or funding to produce. However, local communities were not invited to review or participate in its scope, design or content; that authoring of such publications would take place within archaeology departments and museums was an implicit assumption.

Visits to houses, schools and offices in early 2015 enabled the distribution of 413 copies of the Arabic edition to the three communities, for free. This created a network of personal relationships and opportunities for Fushiya and other team members to capture feedback (; see Näser and Tully Citation2019 on the feedback cycle). Readers described how they gained new perspectives on the value of sherds, previously seen as insignificant and now associated with water jars (zir, plural aziyar), still used in houses today. Grinding stones and ovens were also seen as connections between past and present practices, described as turath (heritage) and associated to memories of their parents and grandparents. Teachers commended the book for expanding resources that would complement the curriculum, which does not consider local history and heritage.

Three years after the book distribution, 74.9% of survey respondentsFootnote5 had kept their copy at home, with the majority (94%) describing the book positively. However, a significant proportion (60%) indicated that insufficient information was provided that related to Nubian heritage that people in the region articulate and celebrate today: languages, music, landscape, traditional houses (see also Rowan Citation2017). Others expressed an interest in further information on other archaeological sites (14%), or the general history of Sudan (11%). The desire for resources which set local heritage (turath) within the broader context of other sites and the history of the country was emphasized. These communities had no access to a library, and the nearest museum was in Kerma, 180 km to the south.

The ‘broadcast’ approach reflects how archaeological interpretation and presentation have been designed for ‘audiences’ of visitors and tourists (van der Linde, van den Dries, and Wait Citation2018), ‘exogenously conceived’ (Humphris, Bradshaw, and Emberling Citation2021, 1131). Though many museums have integrated community perspectives in their programming and displays (see Golding and Modest Citation2013),Footnote6 major museums – on the whole – continue to present their collections through an authoritative ‘institutional’ voice. In an archaeological context, the ‘broadcast’ approach casts local people as passive recipients of knowledge, enshrining archaeologists as the interpreters of the past. Where that local audience has close attachments and connections to the archaeological site, such as Amara West/Abkanisa (emphasized in interviews with community members, see Fushiya Citation2020), this can create unequal power relationships, disenfranchizing the people who have a continuous sociocultural relationship to the sites in question (Atalay Citation2006; Jansen and Pérez Jiménez Citation2017; Pikirayi Citation2016). However, we must also recognize local community and individual agency in choosing not to engage with parts of the material past that surrounds them (see Abu-Khafajah Citation2011).

Nonetheless, these early initiatives provided opportunities for the archaeological team to learn and broaden their perspectives (Buccellati Citation2012), acting as an ‘icebreaker’ in developing relationships between the team and the local communities, in turn building mutual understanding (Humphris and Bradshaw Citation2017). Unintentionally, the broadcast approach created ‘a passage from unfamiliar to the familiar’ (Greer Citation2014, 57), bringing together communities and archaeologists around interpretations of the past. In contrast, some other QSAP-funded projects investigated local interests first, with an aim to better understand the most effective participatory approach that could be deployed (Humphris and Bradshaw Citation2017; Näser and Tully Citation2019; Humphris, Bradshaw, and Emberling Citation2021, 1131).

Collaborative programmes

The community feedback and encouragement to consider turath, at a time when Fushiya embarked upon a doctoral thesis focused on community archaeology with Abkanisa/Amara West as the central case study (Fushiya Citation2020), prompted a pivot towards non-western, local and meanings-based approach to communicating archaeological practices. We sought to explore how local audiences associate – or not – with the site, what aspects of the archaeology interests, alienates or causes resentment, drawing on the practices of public archaeology (Matsuda and Okamura Citation2011). Fushiya’s research, benefitting from perspectives beyond the disciplinary context of Egyptology or Nubian studies, further catalyzed the shift in approach.

Drawing on data from semi-structured interviews and discussions,Footnote7 and school sessions, it became evident that the use of the toponym Amara West – rather than Abkanisa – and the presence of archaeological expeditions comprised of non-Sudanese experts and government representatives (NCAM, police), alienates people and discourages visits to the site. In contrast, personal memories of, and associations with, Abkanisa included small-scale farming, collecting wood, legendary tales about a woman who lived there, and a fertility ritual (mushahara, see Boddy Citation1989). Community memories and experiences of the EES and British Museum excavations were also included within personal, familial and community constructions of meaning.

Sharing archaeological research might allow the community to augment existing local meanings of the place, but also to substantiate or reconsider cultural continuities between the past and present. A shared understanding of ‘Nubian heritage’ (turath) is evidenced by images circulated on social media, or the decoration of Nubian social clubs in Khartoum: palm trees, the saqiya-waterwheel, the ‘Nubian house’, song, dance, and the Nubian language (see Rowan Citation2017). Of course, such definitions change over time and from place to place, though a widespread concern is around how turath is in danger of being lost, especially in the villages threatened by proposed dam construction.

Informed by these community perspectives, we instigated more collaborative modes of engagement. Fushiya secured funding for a book designed for local school children: Life in the Heart of Nubia: Abri, Amara East and Ernetta Island (Fushiya et al. Citation2017). Unlike the earlier project book, this was co-designed with community members interested in heritage: Shireen Ahmed, Hassan Sorta and Fekri Hassan Taha, a local café owner with an interest in heritage who had been identified through the earlier engagement programmes. The team collaborated to agree themes and structure and write text; English and Arabic editions of the 36-page book were printed in Khartoum and the digital files shared to encourage distribution. Ahmed, Sorta and Taha commented that ‘this is our book’, underlining how the collaborative process had fostered a sense of ownership, very distinct to the previous book authored by the archaeological team.

Designed to appeal to children, the colourful layout included many pictures of people and activities alongside buildings and landscapes; song and poetry excerpts were also included. The cover image was painted by Mosab Sorta. Two themes were emphasized throughout the book: (1) continuities between past and present life, and (2) local stories and heritage resources. Each section explores an aspect of life, and draws upon oral histories collected by the team in the three communities. Children and other readers are prompted with questions, to encourage transmission of heritage among the Nubian community and wider Sudanese society (Medani Citation2016; Osman Citation1987): ‘have you seen written Nubian language?’; ‘how many Nubian songs do you know?’; ‘what did ancient people eat?’

Copies of the book (650) were circulated to the Abri Administrative Unit offices and schools from March 2017 onwards, complemented by a heritage programme conducted by Hassan Sorta and Fushiya. This programme used the new publication to discuss certain subjects, such as the temple of Amara East which was partly standing in the nineteenth century (Wenig Citation1977), or the meaning of pottery sherds. Interestingly, the Japanese funding (Toyota Foundation) was interpreted by some in these Nubian communities as international recognition for their heritage: a positive perspective on foreign funding schemes.

This book was followed by a second community book project: Nubia Past and Present. Agriculture, Crops and Food (Ryan, Hassan, and Saad Citation2018). Produced with financing from a United Kingdom research council, this book was inspired by Ryan’s research into agricultural risk management, drawing on interviews with farmers in the area (Ryan et al. Citation2022).Footnote8 Importantly, the creation and subject of the book responded to a specific request from pupils in Ernetta Island school, who requested a community-orientated publication that shared the research. The book team included the same individuals who worked on Life in the Heart of Nubia, but also Mohamed Saad, and Mohamed Hassan Siedahmed, then director of the Kerma Museum. Text, layout and design were collaboratively finished in the Abri area, with English and Arabic editions again printed in Khartoum.

The book explores changing crops, processing and eating practises in living memory and sought to help the community reflect upon – and preserve – local and traditional agricultural knowledge. Aimed at school and adult audiences, it was designed to appeal across generations. Illustrations conveyed the contrast between now lost technologies – such as the saqiya (waterwheel) and the shaduf (a hand-operated water lifting device) – and the irrigation pumps (babur) used today. Excerpts from harvest songs were included, and a glossary in Arabic, English and Nubian documented Nobiin terms for crops, knowledge which is endangered as new commercial crops now predominate. The book also included summaries of the archaeobotanical research from Amara West and regional crop histories.

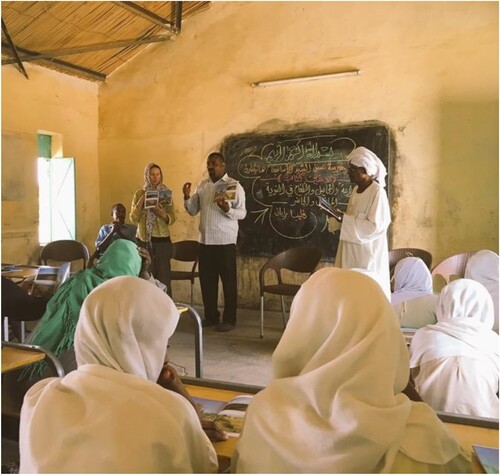

Five hundred copies were distributed in the Abri area, but also Dal and Mufraka downstream, in March 2018, with a further 390 books then distributed in Kerma, Dongola and Khartoum, including to NCAM, museums, university faculties and other cultural institutions. Sessions to introduce the book and its themes were held in schools ().

Figure 4. Ryan and Hassan Sorta lead an Amara East primary school session with the Nubia Past and Present book, in 2019.

Ryan and Saad were subsequently funded by the same research council to write a ‘case-study report’ on the process of creating the book. This reflected on the benefits and difficulties of designing and printing the book whilst in Sudan, the usefulness of photography and illustrations for engaging elderly generations that could not read, and for explaining lost practices to younger generations. The urgency and local interest in recording Nobiin terms for foods and plants, many of which have no exact correlates in Arabic, was also emphasized in the evaluation (Ryan, Saad, and Hassan Citation2019).

Around the same time, Fushiya instigated a project to create a podcast in the Nobiin language. While seeking to address local audiences in their own language, which had long been banned in formal education and is almost entirely restricted to spoken use, this podcast further reflected the project’s shift in approach, as the authoring and narration did not involve project members. Taha, co-author of Life in the heart of Nubia, articulated his own perspectives on Abkanisa/Amara West, drawing upon his discussions with the project team over previous years, but foregrounding the importance of history over recent opportunities: ‘gold and oil will finish, but our history will not’. Fushiya designed and edited the podcast with assistance of an Ernetta-born resident who now lives in Khartoum. Published on the project blog page, nearly 500 downloads have been registered to date.Footnote9

Towards local agency

As the British Museum fieldwork project drew to a close in February 2019, the team sought to facilitate and support the creation of a space for engagement with, and promotion of, local heritage. Fushiya’s survey in 2018Footnote10 had shown that a significant proportion of respondents (34%) were unaware of the orientation area at the ancient site: the community wanted a more accessible location. Furthermore, while our ‘broadcast’ and ‘collaborative’ programmes had contributed to 82% of respondents ascribing an increased importance to archaeology and sites such as Abkanisa/Amara West, 51% expressed the desire for a space in which their living heritage (turath) could be celebrated.

The British Museum project thereafter acted as a facilitator, with access to funds not available locally, in the realization of this community need. A group was convened to make decisions on the format and purpose of the centre, comprised of Rushdi Jamal, representing the community council [lejna shabeya], three school teachers from Amara East and Abri, including Usal Jamal, and Shireen Ahmed (co-author of Life in the Heart of Nubia), the head and secretary of the Abri Administrative Unit, the head of Abri Survey Office, a history graduate and a telecommunications employee with a degree in tourism. Spencer and Saad (representing NCAM) joined this group’s discussions as facilitators. Several locations were considered for the facility, resulting in the group’s decision to repurpose an abandoned old community club (nadi) from the 1940s. This building offered ample space, in a location amidst three of Abri’s main schools and within a 10-minute walk from the market.

Named the Beit il-Turath Abri – the ‘House of Heritage, Abri’ – the space features two display rooms, an arcaded ‘verandah’, an office and small library, and a performance stage (the last a feature of the original nadi). Local craftsmen and volunteers painted Nubian designs on the exterior gate, the upper part of the building walls and plastered the courtyard walls. The first display room presents remains of the ancient past, with a sandstone doorway, stone tools and a reconstructed angareeb (wooden bed) (Lehmann Citation2021) from Abkanisa/Amara West. The ancient objects were approved by NCAM for display, reflecting the continued role of state institutions in shaping access to heritage. Six illustrated text panels seek to link villages and places in the region with the wider history and archaeology of Sudan. Authored by Saad, Sanaa el-Batal (a University of Khartoum anthropologist) and Spencer, the text was reviewed by representatives of the local community and archaeologists active in the region. For many local inhabitants, this was the first time they had seen images or learnt about Kerma cemeteries, Medieval churches or the Greek graffiti found within their region; information on local history and archaeology remains largely inaccessible in publications not available outside of Khartoum, mostly written in European languages.

The second room, dedicated to turath, was approached differently: here the Amara West Research Project procured display cases, but their contents were decided upon by the community group, working with female graduates who live in Abri, facilitated by el-Batal (). At opening, the display featured objects relating to passages of life, the serving and consumption of food, sufi ceremonies and the jertig, an important part of marriage ceremonies. The objects were brought from houses in Abri and the nearby villages of Tabaj, Abri, Amara East and Ernetta, on a loan or donation basis, as awareness of the project spread during preparation of the building. A panel on recent history completes the story from the previous room, and one final panel explains how the space is community-curated. The adjacent covered verandah was used for a pop-up display of heritage objects owned by a man from Kweka, an archaeological site and village 15 km south of Abri. The owner wrote the labels and arranged the display of objects himself.

Computers, printers and label holders will allow the community to re-shape the displays as and when they wish, with ideas put forward around film screenings, musical performances and Nubian language classes. The Faisal Cultural Centre in Khartoum donated a collection of over 1000 books – from history to children’s comics – to form the nucleus of a small library, complemented by donations from the British Museum and DAL Group, a major family-owned enterprise interested in Nubian culture. Organized and catalogued by Amira Alla Eldin Saleh Mohamed from the University of Dongola, this is the only library facility within a radius of 200 km. Secondly, a collaboration with Sudan MemoryFootnote11 – a digitization project dedicated to conserving and promoting Sudanese cultural and documentary heritage, led by Marilyn Deegan and funded by the UK government’s Cultural Protection Fund – provided training and equipment to nine local graduates in how to scan and catalogue photographs, allowing the local community to preserve information embedded within family photograph albums from the mid twentieth century onwards. These represents a rich source for understanding recent history and heritage, architecture, fashion and family traditions, particularly while those who know the subject matter and individuals in each photograph are still alive.

The opening in March 2019, attended by around 100 people from the area, was well received. The Abri Administrative Unit assigned two staff to supervise and manage the facility, while NCAM re-assigned a local ghaffir (guard) to be based in the il-Turath Abri. In principle, it does not depend on archaeological project funding to survive. The purpose and impact of the Beit is uncertain and will undoubtedly evolve, though since 2020 the Covid-19 pandemic, political uncertainty and then conflict in Sudan have severely restricted activities.

Public archaeology futures in Sudan

Nubians have long been recognized as deeply engaged with their history heritage, and landscape (Fernea and Rouchdy Citation2010; Klimowicz and Klimowicz Citation2012; Kronenberg Citation1979; Shinnie Citation1981). The community engagement and research around Amara West confirmed that this is very much the case in the Abri area, and highlighted the distinctive array of local associations between communities and Abkanisa/Amara West, considered turath rather than athar (antiquities).

As this Project pivoted from providing information to listening to and foregrounding community perspectives, a convergence of community and academic interests became more evident. In particular, the community interest in ancient health and diet, climate and life experience resonates with the archaeological research agenda, focused upon lived experience and local agency rather than monuments or narratives of conquest, pharaohs and cultural domination.

Considerable challenges and limitations lie ahead. At a local level, how sustainable will the Beit il-Turath Abri be? Can it represent the plurality of communities in the Abri area? There are numerous inhabitants from Ethiopia, Egypt, the Nuba mountains and western Sudan, some of them children of earlier immigrants to the area, or of Arab tribes settled in Nubia for generations, as elsewhere in Sudanese Nubia (Osman Citation2010). These were not involved or addressed in the initiatives described above, as community representatives were uncomfortable with the subject, given the political climate in early 2019. Such sensitivities also cross national and chronological boundaries: during consultation on the Beit Abri lil-Turath text panels, sections relating to Egypt, Britain and the Ottoman Empire elicited the most debate, whilst some emphasized how the Mahdist armies that resisted British occupation were not well-remembered in this region.

A passion for cultural heritage in this region existed long before the Amara West Research Project, of course, played out in houses, marketplace and cafés, sometimes around objects and site visits, and at social and religious gatherings. Can the Beit il-Turath Abri provide a complementary space for discussing and celebrating a distinctively local turath, particularly in its address to the young, and to visitors from Sudan and beyond?

As the full range of QSAP-funded community archaeology projects, and others, publish their findings and evaluate their impact (see Humphris, Bradshaw, and Emberling Citation2021), it will become possible to explore differences and similarities in the associations ascribed to archaeology by other communities across Nubia. This will, in turn, help inform a more socially inclusive archaeological methodology (see Atalay Citation2012; Greer Citation2014; Mire Citation2011; Pikirayi Citation2016) for future projects, where academic and non-academic perspectives are seen as complementary. These projects broaden our understanding about how various communities in the northern riverine region of Sudan value, engage and (dis)associate themselves with archaeology through research and interactions (Bradshaw Citation2017; Citation2018; Fushiya Citation2020; Humphris and Bradshaw Citation2017; Humphris, Bradshaw, and Emberling Citation2021; Näser and Tully Citation2019; Ryan, Saad, and Hassan Citation2019), in turn changing these communities’ relationships with archaeology (Emberling in Humphris, Bradshaw, and Emberling Citation2021). Though these differences are important to take into account as community engagement activities are designed for and with each community, the symbolic role of an ancient queen (kandaka) in the recent political uprising in Sudan reflects a sense of a shared past that transcends ethnic differences (Fushiya and Radziwiłko Citation2019).

The Sudanese political context was transformed with the fall of the Omar el-Bashir regime in April 2019, resulting in an easing of control over national heritage narratives. National and regional authorities, and local communities, proposed that Nubian classes should be reintroduced (for example during an Old Dongola stakeholder meeting in 2021; Larsen Citation2021). Such political change presented an opportunity to both celebrate regional and community heritage, presenting greater diversity of perspectives, though community representation in government decision making around heritage is not yet envisaged.

The QSAP projects, whilst providing a platform for innovative community collaborations, have also underlined how the modes of practicing archaeology remain set in a framework of structural inequality. Only through the actions and empowerment of those communities adjacent to sites will the structures and framework of the colonial era be truly transformed. The civil war that broke out in April 2023 has of course impeded further developments towards a new framework for community agency in archaeology.

Acknowledgements

The former Director General of NCAM, Dr. Abdelrahaman Ali Mohamed, his colleagues and the many people around Amara West/Abkanisa supported the community work, and ultimately shaped a new approach. As only some could be reached to provide consent (verbal or by WhatsApp) to be named, others have been left anonymous. Translations of interviews, and texts in Arabic and Nobiin, were undertaken by six translators including Shireen Ahmed, Hassan Sorta, Mohamed Hassan Siedahmed, and co-authors Saad and Abd Rabo. We dedicate this article to El Hadi Hassan, Yousri el Said and Karin Willemse, all recently passed away.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Available for download at https://amara-west.researchspace.org (accessed 21/01/2024).

2 https://britishmuseumamarawestblog.wordpress.com/ (accessed 21/01/2024/28/12/2022).

3 Search for #amarawest, and Twitter posts from @NealSpencer, @Beket_Aten, @tomomifushiya, @MVandenbeusch, @Kate_Fulcher, @Jamie_Woodward, @flip_Ryan and @pompei79. On Instagram, see @nealspencer_.

4 For QSAP-funded visitor facilities see Wolf and Onasch (Citation2016); Anderson, elRasheed, and Bashir (Citation2018); Rilly (Citation2018); Tarczewski (Citation2018); Wolf et al. (Citation2018); Welsby (Citation2018, 95); publications are available at https://qsap.org.qa/en/publication.html (accessed 06/05/2022).

5 A survey (January-February 2018) of 199 adults was conducted by Fushiya and five community members, in both Arabic and Nobiin, asking for perspectives on the programmes, the importance of Amara West and local heritage, and possible future heritage programmes.

6 A suite of projects at the Fitzwilliam Museum involve communities as co-researchers: https://fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/research/participation-practice-and-co-creation-research-community (Accessed 21/01/2024).

7 Interviewees provided verbal consent to Fushiya before interviews, whose fieldwork was conducted with approval from the National Corporation of Antiquities & Museums (Sudan) and Leiden University; the British Museum’s Research Board (which acts as an Ethics Committee for the institution’s research projects) also approved the fieldwork. We opted for verbal consent as Fushiya’s previous experiences in the sociocultural and political context of northern Sudan, in which the data presented here was collected, revealed that written consent is not preferred by participants.

8 Ryan’s work followed the code of ethics of the International Society of Ethnobiology (2006), with interviews undertaken with verbal consent, after providing individuals with an Arabic description of the project. The work was undertaken with approval of the National Corporation of Antiquities & Museums (Sudan) and the British Museum’s Research Board (which acts as Ethics Committee for the institution’s research projects).

9 https://britishmuseumamarawestblog.wordpress.com/2018/07/25/amara-west-a-modern-nubian-perspective (Accessed: 02/06/2022).

10 The survey data is available at https://doi.org/10.17026/dans-xkm-fjts, and the survey questionnaire is available at Leiden University Repository, https://hdl.handle.net/1887/138483 as Appendix 1.

11 https://www.sudanmemory.org/stories/abri-house-of-heritage/ (accessed 17 December 2022).

References

- Abd Rabo, Shadia, and Neal Spencer. 2014. “Amara West 1947–50: Inscribed in Nubian Memory.” In Amara West: Living in Egyptian Nubia, edited by N. Spencer, A. Stevens, and M. Binder, 108–109. London: British Museum.

- Abu-Khafajah, Shatha. 2011. “Meaning-Making Process of Cultural Heritage in Jordan: The Local Communities, the Contexts, and the Archaeological Sites in the Citadel of Amman.” In New Perspectives in Global Public Archaeology, edited by Katsuyuki Okamura, and Akira Matsuda, 183–196. New York, NY: Springer New York. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-0341-8_14.

- Anderson, Julie R., R. K. elRasheed, and Mahmoud S. Bashir. 2018. “The Qatar-Sudan Archaeological Project: Drones and Doors: Dangeil 2017–18.” Sudan and Nubia 22: 107–115.

- Atalay, Sonya. 2006. “Indigenous Archaeology as Decolonizing Practice.” American Indian Quarterly 30 (3-4): 280310. https://doi.org/10.1353/aiq.2006.0015.

- Atalay, Sonya. 2012. Community-based Archaeology: Research with, by, and for Indigenous and Local Communities. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press.

- Binder, Michaela. 2017. “The New Kingdom Tombs at Amara West: Funerary Perspectives on Nubian—Egyptian Interactions.” In Nubia in the New Kingdom: Lived Experience, Pharaonic Control and Indigenous Traditions. British Museum Publications on Egypt and Sudan 3, edited by Neal Spencer, Anna Stevens, and Michaela Binder, 591–613. Leuven: Peeters.

- Boddy, Janice. 1989. “Wombs and Alien Spirits Women, Men, and the Zar Cult in Northern Sudan.” In New Directions in Anthropological Writing. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Bradshaw, Rebecca. 2017. “Beyond Identity: The Socio-Economic Impacts of Archaeology on a Non-Descendent Community in Sudan.” PhD diss., School of Oriental and African Studies, University London.

- Bradshaw, Rebecca. 2018. “Fāida shenū? (What is the Benefit?): A Framework for Evaluating the Economic Impacts of Archaeological Employment.” Sudan and Nubia 22: 189–197.

- Buccellati, Giorgio. 2012. “Presentation and Interpretation of Archaeological Sites: The Case of Tell Mozan, Ancient Urkesh.” In Archaeological Sites: Conservation and Management, edited by Sharon Sullivan, and Richard Mackay, 152–156. Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute.

- Byrne, Denis. 2008. “Heritage as Social Action.” In The Heritage Reader, edited by Graham Fairclough, Rodney Harrison, John H. Jameson Jnr, and John Schofield, 149–173. London and New York: Routledge.

- Fairman, Olive. 1990. “The 1938–39 Amara Excavation.” The Egypt Exploration Society Newsletter 6 (October): 3–5.

- Fernea, R. A., and A. Rouchdy. 2010. “Nubian Culture and Ethnicity.” In Nubian Encounters: The Story of the Nubian Ethnographical Survey 1961–1964, edited by Nicholas Hopkins, and Sohair Mehanna, 289–300. Cairo: American University of Cairo Press.

- Fulcher, Kate. 2022. Painting Amara West: The Technology and Experience of Colour in New Kingdom Nubia. British Museum Publications on Egypt and Sudan 13. Leuven: Peeters.

- Fushiya, Tomomi. 2017. “Amara West: Archival Records and Local Memories.” Egyptian Archaeology 51: 33–35.

- Fushiya, Tomomi. 2020. “Valuing Archaeology? The Past, Present, and Future for Local People and Archaeologists in Sudanese Nubia.” PhD diss., Leiden University.

- Fushiya, Tomomi, Shireen Ahmed, Hassan Sorta, and Fekri H. Taha. 2017. Life in the Heart of Nubia: Abri, Amara East and Ernetta Island. Khartoum: British Museum Amara West Research Project.

- Fushiya, Tomomi, and Katarzyna Radziwiłko. 2019. “Old Dongola Community Engagement Project: Preliminary Report from the First Season.” Sudan & Nubia 23: 172–181.

- Golding, V., and W. Modest. 2013. Museums and Communities: Curators, Collections and Collaboration. London: Bloomsbury.

- Greer, Shelley. 2014. “The Janus View: Reflections, Relationships and a Community-Based Approach to Indigenous Archaeology and Heritage in Northern Australia.” Journal of Community Archaeology & Heritage 1 (1): 56–68. https://doi.org/10.1179/2051819613Z.0000000002.

- Harrison, Rodney. 2013. Heritage: Critical Approaches. London: Routledge.

- Humphris, Jane, and Rebecca Bradshaw. 2017. “Understanding ‘the Community’ Before Community Archaeology: A Case Study from Sudan.” Journal of Community Archaeology & Heritage 4 (3): 203–217. https://doi.org/10.1080/20518196.2017.1345364.

- Humphris, Jane, Rebecca Bradshaw, and Geoff Emberling. 2021. “Archaeological Practice in the 21st Century: Reflecting on Archaeologist-Community Relationships in Sudan’s Nile Valley.” In The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia, edited by Geoff Emberling, and Bruce Beyer Williams, 1127–1144. New York: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190496272.013.57.

- Jansen, Maarten E.R.G.N., and Gabina A. Pérez Jiménez. 2017. “The Indigenous Condition: An Introductory Note.” In Heritage and Rights of Indigenous Peoples, edited by Manuel M. Castillo, and Amy Strecker, 25–37. Leiden: Leiden University Press.

- Kleinitz, Cornelia, and Claudia. Näser. 2013. “Archaeology, Development and Conflict: A Case Study from the African Continent.” Archaeologies 9 (1): 162–191. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11759-013-9227-2.

- Klimowicz, Arkadiusz, and Partycja Klimowicz. 2012. “The Socio-Political Context of Polish Archaeological Discoveries in Faras, Sudan.” In European Archaeology Abroad: Global Settings, Comparative Perspectives, edited by Sjoerd J. van der Linde, and Monique H. van den Dries, 287–306. Leiden: Sidestone Press.

- Kronenberg, Andreas. 1979. “Survival of Nubian Traditions.” In Africa in Antiquity: The Arts of Ancient Nubia and the Sudan: Proceedings of the Symposium Held in Conjunction with the Exhibition, Brooklyn, September 29–October 1, 1978 (Meroitica 5.), edited by Fritz Hintze, 173–176. Berlin: Akademie-Verlag.

- Larsen, Peter B. 2021. “From Development Displacement and Salvage Archaeology in Nubia to Inclusive Sustainable Heritage and Development Crafting in Old Dongola, Sudan.” Sudan & Nubia 25: 82–94. https://doi.org/10.32028/Sudan_and_Nubia_25_pp82-94.

- Lehmann, Manuela. 2021. “Angareeb-bed Production in Modern Nubia: Documenting a Dying Craft Tradition.” Sudan & Nubia 25: 11–23. https://doi.org/10.32028/Sudan_and_Nubia_25_pp11-23.

- Marshall, Yvonne. 2002. “What is Community Archaeology?” World Archaeology 34 (2): 211–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/0043824022000007062.

- Matsuda, Akira, and Katsuyuki Okamura. 2011. “Introduction: New Perspectives in Global Public Archaeology.” In New Perspectives in Global Public Archaeology, edited by Katsuyuki Okamura, and Akira Matsuda, 1–18. New York: Routledge.

- McManamon, Francis P. 2000. “Archaeological Messages and Messengers.” Public Archaeology 1 (1): 5–20. https://doi.org/10.1179/pua.2000.1.1.5.

- Medani, Huwaida. 2016. “The Habouba School.” In The Making of Social Capital in Sudan, edited by B. A. A. Ali, Huwaida Medani, and A. A. Osman, 71–92. Khartoum: Madarik.

- Mire, Sada. 2011. “The Knowledge-Centred Approach to the Somali Cultural Emergency and Heritage Development Assistance in Somaliland.” African Archaeological Review 28: 71–91. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10437-011-9088-2.

- Näser, Claudia. 2021. “Past, Present, Future: The Archaeology of Nubia.” In The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia, edited by Geoff Emberling, and Bruce Beyer Williams, 29–47. New York: Oxford University Press. Accessed December 17, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190496272.013.2.

- Näser, Claudia, and Gemmaa Tully. 2019. “Dialogues in the Making: Collaborative Archaeology in Sudan.” Journal of Community Archaeology & Heritage 6 (3): 155–171. https://doi.org/10.1080/20518196.2019.1629742.

- Osman, Ali Mohamed Salih. 1987. “Nubian Culture in the 20th Century: Comments on Session IV.” In Nubian Culture Past and Present: Main Papers Presented at the Sixth International Conference for Nubian Studies in Uppsala, 11–16 August, 1986, edited by Tomas Hägg, 419–431. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell International.

- Osman, Ali Mohamed Salih. 2010. “Nubia.” In Encyclopaedia of Africa, edited by Anthony Appiah, and Henry L. Gates Jr., 253–254. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Pikirayi, Innocent. 2016. “Archaeology, Local Knowledge, and Tradition: The Quest for Relevant Approaches to the Study and use of the Past in Southern Africa.” In Community Archaeology and Heritage in Africa: Decolonizing Practice, edited by Peter R. Schmidt, and Innocent Pikirayi, 112–135. New York: Routledge.

- Pyburn, Karen A. 2011. “Engaged Archaeology: Whose Community? Which Public?” In New Perspectives in Global Public Archaeology, edited by Katsuyuki Okamura, and Akira Matsuda, 29–41. New York: Springer.

- Rilly, Claude. 2018. “The QSAP Programme on the Temple of Queen Tiye in Sedeinga.” Sudan and Nubia 22: 55–64.

- Rowan, Kirsty. 2017. “Flooded Lands, Forgotten Voices: Safeguarding the Indigenous Languages and Intangible Heritage of Nubian Nile Valley.” International Journal of Intangible Heritage 12: 176–187.

- Ryan, Philippa, Mohamed Hassan, and Mohamed Saad. 2018. Nubia Past and Present: Agriculture, Crops and Food. Khartoum: British Museum Amara West Research Project.

- Ryan, Philippa, M. Kordofani, Mohamed Saad, Mohamed Hassan, Matthew Dalton, Caroline Cartwright, and N. Spencer. 2022. “Nubian Agricultural Practices, Crops and Foods: Changes in Living Memory on Ernetta Island, Northern Sudan.” Economic Botany 76: 250–272. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12231-022-09548-5.

- Ryan, Philippa, Mohamed Saad, and Mohamed Hassan. 2019. Nubian Traditional Knowledge and Agricultural Resilience. UKRI Indigenous Engagement Programme Project Report.

- Shinnie, Peter L. 1981. “Changing Attitudes Towards the Past.” Africa Today 28 (2): 25–32.

- Smith, Laurajane, and Emma Waterton. 2009. Heritage, Communities and Archaeology. London: Duckworth.

- Spencer, Patricia. 1997. Amara West I: The Architectural Report. London: Egypt Exploration Society.

- Spencer, Patricia. 2002. Amara West II: The Cemetery and the Pottery Corpus. London: Egypt Exploration Society.

- Spencer, Neal. 2015. “Creating a Neighborhood within a Changing Town: Household and Other Agencies at Amara West in Nubia.” In Household Studies in Complex Societies: (micro) Archaeological and Textual Approaches, edited by M. Müller, 169–210. Chicago: The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.

- Spencer, Patricia. 2016. Amara West III: The Scenes and Texts of the Ramesside Temple. London: Egypt Exploration Society.

- Spencer, Neal. 2017. “Building on New Ground: The Foundation of a Colonial Town at Amara West.” In Nubia in the New Kingdom: Lived Experience, Pharaonic Control and Indigenous Traditions. British Museum Publications on Egypt and Sudan 3, edited by N. Spencer, A. Stevens, and M. Binder, 323–355. Leuven: Peeters.

- Spencer, Neal, Anna Stevens, and Michaela Binder. 2014. Amara West: Living in Egyptian Nubia. London: British Museum.

- Tarczewski, Romuald. 2018. “Construction Work in the Mosque Building (Throne Hall) in Seasons 2015–2017.” In Dongola 2015–2016: Fieldwork, Conservation and Site Management, edited by Włodzimierz Godlewski, Dorota Dzierzbicka, and Adam Łajtar, 243–253. Warsaw: University of Warsaw Press.

- Thomas, Suzie, Carol McDavid, and Adam Gutteridge. 2014. “Editorial.” Journal of Community Archaeology & Heritage 1 (1): 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1179/2051819613Z.0000000009.

- van der Linde, Sjoerd J., Monique H. van den Dries, and Gerry Wait. 2018. “Putting the Soul into Archaeology—Integrating Interpretation into Practice.” Advances in Archaeological Practice 6 (3): 181–186. https://doi.org/10.1017/aap.2018.22.

- Welsby, Derek. 2018. “Qatar-Sudan Archaeological Project: Excavations and Other Activities at Kawa–the 2017–18 Season.” Sudan and Nubia 22: 89–95.

- Wenig, Stefffen. 1977. “Der meroitische Tempel von Amara.” In Ägypten und Kusch: Fritz Hintze zum 60. Geburtstag gewidmet. Schriften zur Geschichte nd Kultur des Alten Orients 13, edited by Erika Endesfelder, Karl-Heinz Priese, Walter Friedrich Reineke, and Steffen Wenig, 459–475. Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Willemse, Karin. 2017. “Urgent Anthropology Research in the Abri Area.” The British Museum Newsletter Egypt and Sudan 4: 35.

- Wolf, Simone, and Hans-Ulrich Onasch. 2016. A New Protective Shelter for the Royal Baths at Meroë (Sudan). Berlin: Deutsches Archäologisches Institut.

- Wolf, Pawel, Alexandra Riedel, Mahmoud S. Bashir, Janice W. Yellin, Jochen Hallof, and Saska Büchner. 2018. “The Qatari Mission for the Pyramids of Sudan: Fieldwork at the Meroe Royal Cemeteries: A Progress Report.” Sudan and Nubia 22: 3–28.

- Woodward, Jamie, Mark Macklin, Neal Spencer, Michaela Binder, Matthew Dalton, Sophie Hay, and Andrew Hardy. 2017. “Living with a Changing River and Desert Landscape at Amara West.” In Nubia in the New Kingdom: Lived Experience, Pharaonic Control and Indigenous Traditions. British Museum Publications on Egypt and Sudan 3, edited by Neal Spencer, Anna Stevens, and Michaela Binder, 225–255. Leuven: Peeters.