Abstract

Objective: The goal of the study was to assess the feasibility of Laparoscopic Minimally Invasive Inguinal Lymph Node Dissection (L-MILND) for carcinoma of the vulva where sentinel lymph node biopsy could not be done. Laparoscopic Minimally Invasive Inguinal Lymph Node Dissection (L-MILND) is a procedure developed to decrease morbidity associated with inguinal lymphadenectomy while maintaining acceptable oncological outcomes. Initial experience and feasibility of this technique at the authors’ institution is reported.

Setting: Dr George Mukhari Academic Hospital/Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University.

Patients: Sixteen L-MILND performed in nine patients with T1b squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva from May 2016 to April 2020. This is a retrospective analysis of the preoperative, intraoperative and postoperative characteristics.

Results: The median age was 40 years (37–71 years). L-MILND’s median duration and the radical wide local excision was 223 ± 40 minutes (180 to 300 minutes). There were no intraoperative complications. The mean drain output per patient of both inguinal areas was 315 ml (50–990 ml). On average, drains were removed on day 6 (range 3–10 days). The mean number of nodes harvested was 5 (range 0–32 nodes). One patient had 1 positive node out of 32 harvested. The postoperative complications included: lymphoedema (1 groin, 6.25%), seroma (6 groins, 37.5%) and lymphorrhea (4 groins, 25.0%). Overall follow-up has been 3–50 (mean 28.3 months) months, and all patients were alive with no disease.

Conclusion: The significant advantage of L-MILND appears to be the low rate of inguinal wound complications that may be associated with open procedures. This nevertheless comes at the expense of long operative times and seroma formation. This procedure is feasible and safe, though there is a need for large prospective studies with extended follow-up.

Introduction

Vulval carcinoma is uncommon, accounting for 2% to 5% of gynaecological cancers, with squamous cell carcinoma as the most common histological type.Citation1 It has been surgically staged since 1988 and the staging system was updated in 2009 by the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO). The stage will depend on the size of the lesion, amount of lymph node metastasis, extracapsular spread of the metastasis, involvement of adjacent structure and distant metastasis.Citation2 The status of inguinal lymph nodes is an important prognostic factor that determines survival in patients with carcinoma of the vulva. Most patients will have early stage disease, for which the standard treatment is wide local excision and inguinofemoral lymph node dissection.Citation3 This procedure is associated, in 85% of patients, with surgical morbidity such as wound breakdown, cellulitis, lymphocele, lymphoedema and infection.Citation4 But only 25–35% of early stage vulva cancers have lymph node metastasis.Citation5–7 There are different techniques with variable outcomes in the literature seeking to reduce groin morbidity after inguinofemoral nodal dissection, including sparing of the saphenous vein,Citation8 Sartorius muscle transpositionCitation9 and preservation of fascia lata.Citation7 Furthermore, to try to reduce groin surgical morbidity, a sentinel lymph node procedure was adopted for vulval carcinoma and found to be feasible for cancer of the vulva.Citation10 The GROINSS V I study demonstrated the SLN algorithm to be safe in vulval cancer, but only for patients with well-differentiated, small unifocal lesions of <4 cm,Citation10 excluding patients with operable early stage disease larger than 4 cm and/or poorly differentiated multifocal disease. The development of laparoscopic inguinofemoral lymph node dissection was first described by Bishoff to breach this gap. He described a technique of endoscopic inguinofemoral node dissection in two cadavers and one live patient.Citation11 This novel technique was found to be associated with low groin morbidity (wound breakdown and cellulitis) in patients with penile cancer, melanoma and recently vulval carcinoma, compared with the standard open technique.Citation12–14 All the above authors use what is called a LEG approach, for which the stepwise approach was described by Master and colleagues in 2009.Citation15

We report our experience and results of the first series of L-MILND performed by our group in South Africa between May 2016 and April 2020. This is a feasibility study that provides a retrospective analysis of the preoperative, intraoperative and postoperative data.

Materials and method

A retrospective study at Dr George Mukhari Academic Hospital/Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University is presented. After approval by the institutional research ethics review committee, a retrospective review of records of patients who underwent L-MILND for vulval carcinoma was carried out. Patient identifiers were anonymised for analysis. A total of 9 patients who had 16 L-MILND procedures were identified. Seven patients had bilateral laparoscopic inguinal node dissections, one patient underwent laparoscopic inguinal node dissection on the left side only, and one patient had only a right-sided laparoscopic inguinal lymphadenectomy. The following parameters were analysed: operative time, blood loss, intraoperative complications, drain output, day of drain removal, number of lymph nodes harvested, the histological status of the lymph nodes, and recurrence on follow-up. Consent for participation in the study was given.

Data management was performed using Microsoft Excel, 2018 (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, WA, USA). Data analysis was performed using the Stata 14.2 (StataCorp LLP, College Station, TX, USA) software package. Descriptive methods involved the expression of frequencies and percentages; continuous variables were expressed as means with standard deviations with ranges.

Surgical procedure

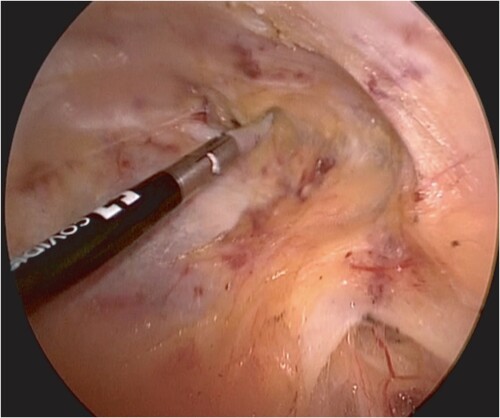

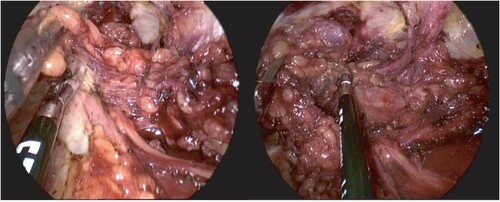

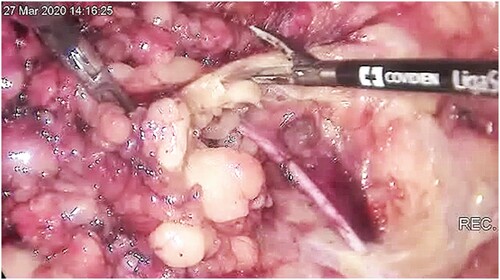

Patients were counselled and signed consent for the procedure. The procedure was done under general anaesthesia and was performed as described earlier.Citation15 We used the LEG approach. The patient was placed in a supine position with the legs externally rotated and abducted. The room setup and patient position are shown in . The patient was cleaned and draped. We made a 10 mm incision 2 cm caudal to the femoral triangle’s apex, extending the incision to below Scarpa’s fascia. We then developed a working space with scissors and finger blunt dissection. A 5 cm working space was developed in this fashion. A 10 mm port was then inserted into the incision, and carbon dioxide (CO2) gas insufflated to pressure of 10 mmHg; two additional 5 mm ports were inserted under vision about 5 cm lateral and medial to the vision port (). The working space was extended by dissection with a LigaSure (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA) instrument up to 2 cm cranial to the inguinal ligament, the lateral border of Sartorius and the adductor muscle (). The superficial lymph node basin is dissected from the floor of the femoral triangle (), sparing the saphenous vein (). The nodes are then delivered, the incision closed and suction drain left in situ ().

Figure 1: Room setting, with laparoscopy stack placed at the patient’s head, with patient’s thighs abducted and internally rotated to access femoral triangle.

Figure 2: (A) 10 mm vision port placed 2 mm caudal to the apex of the femoral triangle with telescope inserted. (B) Second trocar (5 mm) inserted under vision 5 cm medial to the vision port. (C) All THREE ports inserted and working space developed further cranially.

Results

gives patients’ background characteristics. A total of 9 patients underwent L-MILND from May 2016 to April 2020, and among these 16 groins were dissected using L-MILND. The median age of the patients was 40 years (range, 37–71 years). Mean BMI was 30 (range, 21.3–42.1). Seven patients were HIV-positive and 2 had no comorbid diseases. All our patients had radical wide local excision (WLE) and 2 had only unilateral L-MILND. gives perioperative and pathological characteristics of the patients. Eight patients had no lymph node metastasis (pT1bN0M0), whereas one patient had 1 metastatic lymph node (pT1bN1aM0). The mean duration of surgery was 223 ± 40 minutes (180 to 300 minutes). We determined the duration of surgery from induction of anaesthesia to the extubation of the patient because it was the consistently recorded time in the records. Average drain output was 314.9 ± 359.9 ml. On average the drain was removed on day 6 (3–10 days). Two patients experienced vulva wound breakdown and stayed in the hospital for 28 and 30 days respectively. The other 7 patients stayed in the hospital on average for 4 (range 3–10) days. The median number of lymph nodes harvested was 5 (range 0–32 nodes). shows lymph node harvest per groin.

Table 1: Patients’ background characteristics

Table 2: Perioperative and pathological characteristics

Table 3: Lymph node harvest for each groin by L-MILND

There was no groin-related wound breakdown, skin necrosis or cellulitis reported. Only lymphoedema, lymphorrhea and seroma complications were noted. The per groin postoperative complications were lymphoedema (1 groin, 6.25%), seroma (6 groins, 37.5%) and lymphorrhea (4 groins, 25.0%).

Ten groins had no complications recorded; for further details, see . All patients had squamous cell carcinoma; we spared the great saphenous vein in all patients, blood loss associated with the laparoscopic inguinal lymphadenectomy was negligible and there were no intraoperative complications. Four (44.5%) patients required adjuvant treatment for close resection margins on the vulva, and 5 (55.5%) did not require any adjuvant treatment. Median follow-up was 38 months (range 3–50 months) and all patients were alive without any evidence of disease recurrence.

Table 4: Postoperative complications

Discussion

We address the feasibility and complication profile of nine patients who had L-MILND and simple vulvectomy for carcinoma of the vulva at our institution. Though a small series, we found that the procedure to remove the nodes appears safe and feasible with no significant intraoperative complication. The significant advantage of the minimally invasive procedure is that it appears to reduce wound-related complication length of stay in the hospital after the surgery. Having said this, however, some complications did arise specific to the inguinal areas, but they were relatively mild, and none of these complications resulted in an additional stay in hospital.

Our results showed a mean operating time of 223 minutes (range 180–300) for the L-MILND and simple vulvectomy. In comparative studies, a significantly longer operative time was recorded with minimally invasive approach as compared with open techniques. Zhang and colleagues in their study comparing 48 patients who underwent L-MILND (21 patients) and standard inguinal lymphadenectomy (27 patients) in patients with vulval carcinoma, reported mean operative times were 109 ± 29.5 minutes and 45.3 ± 5.1 minutes, respectively (p < 0.001).Citation16 Tobias-Machado et al. performed standard inguinal lymphadenectomy in 1 limb and L-MILND in the contralateral limb in 10 patients with penile cancer. They found operative time to be significantly longer in the L-MILND compared with the standard open procedure (126 vs. 92 minutes).Citation12 Additionally, Abbot et al. in melanoma patients found operative time in L-MILND to be longer than in an open procedure (245 vs. 138 minutes).Citation17 A systematic review by Liu and colleagues reported a total of 9 studies containing 249 L-MILND procedures in 138 patients; the operative time among these studies ranged between 62 and 110 minutes.Citation18

In our study, the operative time included time to administer the anaesthetic, positioning of the patient, time for the L-MILND, and time to complete the simple vulvectomy. This contributed to longer operative time in our study.

The mean drain output in our study was 314 ml (50 to 990 ml), and the drain was removed at mean on day 6 (3–10 days). The drain appears to have been removed at between 6 and 9.8 days across the reports in the systematic review of L-MILND by Liu and colleagues,Citation18 although Zhang et al. reported longer postoperative drainage duration with L-MILND vs. open technique, 16 days vs. 8 days respectively.Citation16 L-MILND shows longer postoperative lymph drainage. The mean lymph node yield in our study was 5 (0–32) per groin, but of note was that there was no harvest from two groins, 1 node from 1 groin and 2 nodes from 2 groins, so that of 16 L-MILND performed in our study, 5 groins had only 0–2 nodes. There have not been any groin recurrences after follow-up of 3 to 50 months, though follow-up was too short to reach any conclusions on oncological outcomes.

Our lymph node yield is variable. There are variable reports on how the number of lymph nodes harvested affects the oncological outcome. In one, it was reported that a lymph node count of less than 9 was related to groin recurrence,Citation19 although Diehl et al. noted that dissection of more than 6 lymph nodes in each groin does not improve groin recurrences in patients with vulval cancer,Citation20 whilst a study by Stehman et al. found that lymph node count in stage 1 vulval carcinoma was not associated with groin recurrence rate.Citation21 Besides surgeon proficiency, lymph node count depends on patient characteristics and pathologist expertise. Patient characteristics include anatomy, age, body mass index, immune status and exposure to toxins, which affect lymph node yield. Variability among pathologists on how nodes are retrieved from fibrofatty tissue and interobserver and intraobserver variably at microscopy on how lymph nodes are examined among pathologists both may affect lymph node yield.Citation22 These factors make the lymph node count an unreliable measure of surgery quality.

The L-MILND certainly is feasible, but it does appear to increase the time needed for the entire surgery significantly. In our hands, there was variable outcome in the number of nodes removed from each groin, and on two occasions no nodes were harvested from a groin region. Although this is the case and of concern to us, the literature does not conclude or specify the minimum number of lymph nodes recommended to predict or exclude the likelihood of inguinal recurrences and, to date, in our series there have not been any recurrences after a median follow-up of 38 months.

We had no major groin wound-related morbidity in our cohort. The L-MILND does not interfere with completing the simple vulvectomy and only two patients that had a protracted stay in hospital and recovery, which was due to a breakdown of the vulvar incisions. We had lymphoedema, lymphorrhea and seroma occurring in 6.25%, 25.0% and 37.5% of groins, respectively. Zhang and colleagues in their study found wound complications to be significantly rare with a minimally invasive approach compared with a standard open approach (4.8% vs. 55.6%), and there was no significant difference in the incidence of lymphocele and lymphoedema in their study.Citation16 Furthermore, patients who underwent a minimally invasive approach experienced higher body image scores and cosmetic scores.Citation16 In a systematic literature review of 10 series (236 minimally invasive inguinal node dissection) that included 168 patients, wound-related complications ranged between 0% and 13.3%; lymphatic/seroma-related complications ranged between 4% and 38%.Citation23 Jain et al. reported seroma, lymphoedema, lymphorrhea and cellulitis of 27.3%, 27.3%, 4.5% and 9.1% of groins, respectively. No major inguinal wound-related complications were reported in the study.Citation24

The significant advantage of MILND is the reduction in inguinal incision wound complications, especially wound breakdown, which may increase the hospital stay and rate of readmission for wound care. Seroma formation is a frequent complication of L-MILND. Risk factors for the development of seroma in L-MILND are ipsilateral lymphoedema, use of large suction bulbs, number of metastatic lymph nodes, increased BMI, age and drain output 24 hours before removal. There is no reliable method to reduce this complication.Citation25

Conclusion

Bearing in mind the limitations (retrospective nature, single institution, single surgeon and selection bias) of our study, L-MILND is a safe and feasible operative technique in patients with vulval carcinoma but the inguinal nodal harvest is not consistently predictable. Our result shows that there is a low groin wound-related morbidity, especially with a view to groin skin breakdown, cellulitis, lymphoedema, seroma formation or lymphorrhea, with satisfactory oncological outcomes. More studies must take place, especially multicentre randomised or well-designed observational studies. Nevertheless, the available studies, including ours, shows that it is a safe, feasible, although time-consuming procedure.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the patients who agreed to be part of this study, and also our trainees (registrars who assisted in the procedures), anaesthesiology team, scrub technicians and nursing staff who took care of these patients.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data from seven patients in this series were presented in the South African Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologist (SASOG) congress held on 7 to 11 March 2020.

Data availability statement: Data supporting the study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Rogers LJ, Cuello MA. Cancer of the vulva. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2018;143:4–13.

- Pecorelli S. Revised FIGO staging for carcinoma of the vulva, cervix, and endometrium. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2009;105(2):103–4.

- Levenback Morris M, Burke TW, Gershenson DM, et al. Groin dissection practices among gynecologic oncologists treating early vulvar cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 1996;62:73–7.

- Gaarenstroom KN, Kenter GG, Trimbos JB, et al. Postoperative complications after vulvectomy and inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy using separate groin incisions. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2003;13(4):522–7.

- Burger MP, Emanuels AG, Krans M, et al. The importance of the groin node status for the survival of T1 and T2 vulval carcinoma patients. Gynecol Oncol. 1995;57(3):327–34.

- Hacker NF, Berek JS, Castaldo TW, et al. Radical vulvectomy and bilateral inguinal lymphadenectomy through separate groin incisions. Obs Gynecol. 1981;58(5):574–9.

- Bell JG, Lea JS, Reid GC. Complete groin lymphadenectomy with preservation of the fascia lata in the treatment of vulvar carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2000;77(2):314–8. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10785485

- Zhang X, Sheng X, Niu J, et al. Sparing of saphenous vein during inguinal lymphadenectomy for vulval malignancies. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;105(3):722–6. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17408728

- Judson PL, Jonson AL, Paley PJ, et al. A prospective, randomized study analyzing sartorius transposition following inguinal-femoral lymphadenectomy. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;95(1):226–30. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15385136

- Van der Zee AG, Oonk MH, De Hullu JA, et al. Sentinel node dissection is safe in the treatment of early-stage vulvar cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(6):884–9. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18281661

- Bishoff JT, Basler JW, Teichman JM, et al. Endoscopic subcutaneousmodified inguinal lymph node dissection (ESMIL) for squamous cellcarcinoma of the penis. J Urol. 2003;169(78):301.

- Tobias-Machado M, Tavares A, Ornellas AA, et al. Video endoscopic inguinal lymphadenectomy: a new minimally invasive procedure for radical management of inguinal nodes in patients with penile squamous cell carcinoma. J Urol. 2007;177(3):953–7; discussion 958.

- Delman KA, Kooby DA, Ogan K, et al. Feasibility of a novel approach to inguinal lymphadenectomy: minimally invasive groin dissection for melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17(3):731–7. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20183910

- Xu H, Wang D, Wang Y, et al. Endoscopic inguinal lymphadenectomy with a novel abdominal approach to vulvar cancer: description of technique and surgical outcome. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011;18(5):644–50. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21872170

- Master V, Ogan K, Kooby D, et al. Leg endoscopic groin lymphadenectomy (LEG procedure): step-by-step approach to a straightforward technique. Eur Urol. 2009;56(5):821–8. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19640633

- Zhang M, Chen L, Zhang X, et al. A comparative study of video endoscopic inguinal lymphadenectomy and conventional open inguinal lymphadenectomy for treating vulvar cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2017;27(9):1983–9. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28885273

- Abbott AM, Grotz TE, Rueth NM, et al. Minimally invasive inguinal lymph node dissection (MILND) for melanoma: experience from two academic centers. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20(1):340–5.

- Liu CE, Lu Y, Yao DS. Feasibility and safety of video endoscopic inguinal lymphadenectomy in vulvar cancer: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2015;10(10):e0140873. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26496391

- Van Beekhuizen HJ, Auzin M, Van Den Einden LCG, et al. Lymph node count at inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy and groin recurrences in vulvar cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2014;24(4):773–8.

- Diehl A, Volland R, Kirn V, et al. The number of removed lymph nodes by inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy: impact on recurrence rates in patients with vulva carcinoma. Arch Gynecol Obs. 2016;294(1):131–6. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26498758

- Stehman FB, Ali S, DiSaia PJ. Node count and groin recurrence in early vulvar cancer: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;113(1):52–6. Available from: https://doi.org/http://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.12.028

- Parkash V, Bifulco C, Feinn R, et al. To count and how to count, that is the question: interobserver and intraobserver variability among pathologists in lymph node counting. Am J Clin Pathol. 2010;134(1):42–9.

- Sommariva A, Pasquali S, Rossi CR. Video endoscopic inguinal lymphadenectomy for lymph node metastasis from solid tumors. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2015;41(3):274–81.

- Jain V, Sekhon R, Giri S, et al. Robotic-assisted video endoscopic inguinal lymphadenectomy in carcinoma vulva: our experiences and intermediate results. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2017;27(1):159–65. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27870714

- Contreras N, Jakub JW. The achilles heel of minimally invasive inguinal lymph node dissection: seroma formation. Am J Surg. 2020;219(4):696–700. Available from: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2019.06.010