ABSTRACT

Background

Hospitalists may work in a variety of clinical settings to manage COVID-19 cases. However, the extent of their involvement in COVID-19 care is unknown, particularly in hospitals without infectious disease (ID) specialists.

Methods

This study aimed to confirm whether hospitalists provided COVID-19 management in various clinical settings when ID specialists were unavailable. We conducted a multicenter cross-sectional study using a web-based questionnaire. The participants were full-time hospitalists working in Japanese academic community-based hospitals. The study period was from 15 January 2021 to 15 February 2021, during Japan’s third wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. The primary outcome was the rate of hospitalists participating in COVID-19 inpatient management in hospitals with or without ID specialists.

Results

ID specialists were absent in 31% of small hospitals (those with fewer than 249 registered beds), but only 4% of large hospitals (p < 0.001). Hospitalists were more likely to manage both COVID-19 inpatient care and emergency department care in hospitals without than with hospitals with ID specialists (76 versus 56% (p = 0.01) and 90 versus 73% (p = 0.01), respectively). After adjusting for confounders by multivariate analysis, hospitalists who worked in hospitals without ID specialists had higher odds of participating in COVID-19 inpatient care than those who worked in hospitals with such specialists (adjusted odds ratio: 3.0, 95% CI: 1.2–7.4).

Conclusion

Hospitalists were more likely to provide COVID-19 inpatient care in various clinical settings in hospitals without ID specialists.

Introduction

During the Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak, problems have not been limited to respiratory illness, but have also included multi-organ failure, intensive care, and geriatric issues, necessitating various care approaches [Citation1,Citation2]. Hospitalists have been defined as physicians who provide comprehensive acute care services for inpatients [Citation3,Citation4]. Hospitalists have been asked to play a central role in COVID-19 management because they have exceptional collaboration skills, show visible leadership, provide care for patients with infectious diseases (ID), and have clinical reasoning skills to diagnose a fever’s origin [Citation5–7]. Our previous studies showed that hospitalists exhibit the following skills for managing COVID-19: clinical skills to tackle a wide range of medical problems, clinical reasoning and triage skills, ID management skills, medical safety, and multi-professional collaboration [Citation8].

Hospitalists have assumed a central role in areas where specialists are absent. The hospitalist system improves outcomes and various factors, including the length of hospital stay, cost-effectiveness, and quality of care for patients with ID, such as aspiration pneumonia and urinary tract infection [Citation9–11] The clinical work style of Japanese hospitalists is based on a hybrid model, meaning that the practice setting is not limited to inpatient care but also includes a variety of clinical settings: outpatient care, emergency department management, and critical care. In Japan, small-to-medium-sized hospitals with less than 300 beds comprise 80% of all hospitals, resulting in a marked demand for hybrid hospitalists who can work in various clinical settings [Citation12,Citation13]. The involvement of ID specialists improves clinical outcomes in ID cases [Citation14]. Furthermore, ID specialists are essential in the COVID-19 era, with respect to diagnosis, infection prevention, and treatment [Citation15]. However, numbers of ID specialists are limited in Japan. In 2019, there were only 1,491 board-certified ID specialists [Citation16]. Pulmonologists mainly took care of the inpatient COVID-19 cases in hospitals without ID specialists or hospitalists in Japan.

We hypothesized that hospitalists assume more diverse clinical roles in hospitals without ID specialists. This study aimed to confirm whether hospitalists provided COVID-19 management in various clinical settings when ID specialists were unavailable.

Method

Study design, setting, and participants

We conducted a multicenter cross-sectional study using a web-based questionnaire, Google Forms service. We distributed Web-based questionnaires to hospitalist division chiefs. The study was conducted from 15 January 2021 to 15 February 2021, during Japan’s third wave of the COVID-19 pandemic (1 November 2020 to 31 March 2021), which did not involve a lockdown, COVID-19 vaccines were not available, and the predominant strain was the B.1.1.214 variant [Citation17,Citation18]. Epidemiological data later showed that among patients hospitalized with COVID-19, 6.5% required intensive care and 5.8% died during this third wave [Citation17].

We surveyed hospitalists working in academic community-based hospitals with at least five full-time hospitalists. We used convenience sampling to select some of these hospitals in Japan from the hospitalist information network. This was because of the lack of a comprehensive nationwide registry of hospitalist divisions. Two Japanese hospitalists consulted and selected academic community-based hospitals where hospitalists worked and met the abovementioned criteria. We excluded full-time hospitalists in the hospitalist division with four or fewer hospitalist physicians because we hypothesized that the division might need at least five full-time hospitalists to manage various work settings, such as COVID-19 inpatient care, emergency department management for febrile patients, and outpatient clinics. We also excluded university hospitals. This was because in Japanese university hospitals, severe COVID-19 patients are managed by intensive care specialists, and moreover, COVID-19 patients with moderate severity tend to be hospitalized in community hospitals. In addition, the wards of Japanese university hospitals are mainly managed by specialists, and few wards are managed by hospitalists. Most COVID-19 cases were confirmed by nucleic acid amplification test equipped in each individual hospital’s laboratory.

Clinical settings associated with Japanese hospitalists

In Japan, hospitalists provide emergency care because most small-to-medium-sized hospitals do not have emergency departments with full-time emergency physicians [Citation13]. Therefore, the management of fever and COVID-19-positive patients requiring emergency care is one of the responsibilities of hospitalists in Japan.

Hospitalists may be involved in critical care, ID consultation, and infection control in small-to-medium-sized community hospitals that do not have ID or critical care specialists in Japan. Considering the wide range of clinical settings of Japanese hospitalists, we included different clinical settings as secondary outcomes.

Data source, variables, and outcomes

All variables were collected through the Google Forms service. The data were classified into hospitalist physician-level and hospital-level. Hospitalist physician-level data included sex, postgraduate year, number of hospitalists in the division, number of inpatient beds managed by the division, and number of hospitalists participating in the infection control team. Hospital-level data included the population of the city where the hospital is located, registered number of hospital beds, registered number of intensive care unit beds, absolute number of ambulance visits, and absence of ID and pulmonary specialists. The primary outcome was the rate of hospitalists participating in COVID-19 inpatient management in hospitals with and without ID specialists. The secondary outcome was the percentage of hospitalists who provided care in the following work settings: outpatient clinic, emergency department management for febrile patients, intensive care unit specifically for COVID-19 cases, consultation service associated with COVID-19, developing hospital guidelines for COVID-19 care, and infection control management in the hospital. The exploratory outcome was the hospitalists’ perspective on the management structure for COVID-19 in the hospital.

Statistical analyses

We present numbers and percentages for categorical variables and medians and the interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables in hospitalist and physician- and hospital-level data. We collected clinical outcomes based on a 6-point Likert scale and defined the upper three scales as an involved work setting. We compared hospitals with and without ID specialists using the Chi-squared test for categorical variables and Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables.

We performed multivariate analysis for the primary outcome using nominal logistic analysis to correct for confounding.

We selected the following core confounders based on theoretical considerations: the number of hospital beds, number of hospitalists in the department, and whether pulmonologists were available. These factors were considered to be associated with both COVID-19 inpatient care by hospitalists and the presence of an ID specialist, which are the criteria for confounders. We performed two sensitivity analyses using different models: the first model adjusted for confounders at the hospitalist-physician level; the second model adjusted for confounders at the hospital level.

We also calculated the adjusted odds ratio and 95% confidence interval by multivariate analysis. We converted ordinal variables into binary variables to detect odds ratios. We also calculated odds ratios, 95% confidence intervals, and p-values for all confounders associated with the primary outcome.

All statistical analyses were performed using JMP version 16.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, U.S.A.). All reported p-values were two-tailed, and p-values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Nara City Hospital Institutional Review Board approved the study. The approval number was 23–2. On the Google Form, all participants consented to the use of the study data.

Results

Baseline characteristics of hospitalist physicians and hospitals

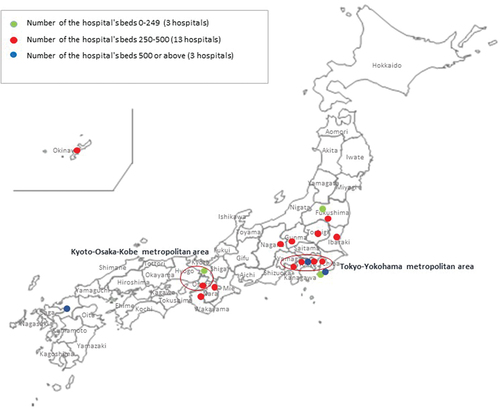

We selected 31 academic community-based hospitals in Japan based on the hospitalist information network. We included hospitalists using two steps. The first step was the hospital phase, and we included 19 hospitals (response rate: 61%) that responded to the e-mail. The second step was the hospitalist phase. We sent the questionnaire to 294 hospitalists who worked at the 19 responding facilities. One hundred and thirty-two hospitalists responded to the questionnaire (response rate: 44.9%) and were included in the analysis (, Supplement 1). Five hospitals belonged to the Tokyo-Yokohama metropolitan area, and two belonged to the Kyoto-Osaka-Kobe metropolitan area among the 19 hospitals (). The city populations of the hospitals were matched between hospitals with and without ID specialists. However, the postgraduate years of hospitalists were fewer in hospitals without than with ID specialists (p = 0.005). ID specialists were absent in 31% of small hospitals (those with fewer than 249 registered beds), but only 4% of large hospitals (p < 0.001).

Hospitals without ICU beds and with fewer ambulance visits had a higher proportion of ID specialists being absent than those with ICU beds and more ambulance visits (p < 0.001). Hospitals without ID specialists had smaller hospitalist departments with nine or fewer hospitalists (46%) than those with ID specialists (21%) (p = 0.001). However, there was no significant difference in the number of inpatient beds managed by hospitalists between hospitals with and without ID specialists (p = 0.3). Hospitals without ID specialists also had a higher proportion of pulmonary specialists being absent (61%) than those with ID specialists (92%) (p < 0.001) ().

Table 1. The baseline characteristics of hospitals with and without ID specialists.

Hospitalists were involved in various COVID-19-related work settings

Hospitalists working without ID specialists had a more comprehensive range of work settings than those working with ID specialists. The percentage of hospitalists involved in outpatient clinics was similar between hospitals with (89%) and without (83%) ID specialists. However, hospitalists working on both COVID-19 inpatient wards and involved in emergency department management for febrile cases were more common in hospitals without than with ID specialists: 76 versus 56%, and 90 versus 73%, respectively (). Rates of hospitalists working in intensive care units for COVID-19, consultation management related to COVID-19 care, developing guidelines for COVID-19, and infection control management were similar between hospitals with and without ID specialists ().

Table 2. Hospitalist work area related to COVID-19.

Multivariate analysis associated with hospitalist inpatient management of COVID-19

Multivariate analysis, after adjustment for confounders, also showed that the absence of ID specialists in the hospital was significantly associated with hospitalists providing inpatient care for COVID-19 (). After adjusting for preselected confounders by multivariate analysis, hospitalists were more involved in COVID-19 inpatient management in hospitals without rather than with ID specialists (adjusted odds ratio: 3.0, 95% CI: 1.2–7.4, p = 0.02). In sensitivity analysis, hospitalists were also more involved in COVID-19 inpatient management without ID specialists after adjusting for hospitalist-based confounders (adjusted odds ratio: 2.9, 95% CI: 1.2–6.6, p = 0.02), and hospital-based confounders (adjusted odds ratio: 2.4, 95% CI: 1.0–5.8, p = 0.04).

Table 3. All funders and Odds Ratio and p value associated with hospitalist inpatient management of COVID-19.

Hospitalists’ expected role in response to COVID-19

The presence or absence of ID specialists influenced the expectation for hospitalists to comprise the primary division for COVID-19 management across hospitals. Hospitals without ID specialists had a higher rate of considering hospitalists as constituting the primary division for COVID-19 management than those with ID specialists (80 versus 35%, respectively). Conversely, hospitalists considered ID specialists as the primary division for COVID-19 management (50%) in hospitals with such specialists ().

Table 4. Divisions recognized as the frontline division in managing COVID-19 in the hospital.

Discussion

We demonstrated that hospitalists working in hospitals without ID specialists were more involved in COVID-19 inpatient care and emergency department management for febrile cases than hospitalists working with ID specialists. Hospitalists’ involvement in outpatient clinics was similar across hospitals.

Hospitals without ID specialists tended to be smaller, with have fewer intensive care unit beds, fewer ambulance visits, fewer hospitalist physicians, and fewer pulmonologists than hospitals with ID specialists. Hospitalists may be considered the frontline division that provides COVID-19 care in hospitals without ID specialists.

Hospitalists had the potential to reduce the length of hospital stay for ID in previous studies [Citation9–11,Citation19]. Collaboration between hospitalists and ID specialists will likely improve the quality of care for ID cases, especially in the following three domains: diagnostics, antimicrobial therapeutics, and antimicrobial stewardship [Citation20]. In rural hospitals without ID specialists, the transfer rate for ID consultations is reported to be 0.01%, and it is imperative that hospitalists provide infectious disease care in these settings [Citation21].

Another suggestion of this study was that hospitalists could complement the role of ID specialists, particularly in small-sized hospitals. ID specialists play an essential role in various fields related to ID, such as infection prevention and control, antimicrobial stewardship, emergency preparedness, and the response to a pandemic [Citation22]. However, in a previous study conducted in Japan, the COVID-19 pandemic did not increase the number of medical students who chose to be ID specialists. Furthermore, 11% of medical students expressed hesitancy to become ID specialists [Citation23]. Although increasing the number of ID specialists in Japan is essential, another strategy is required to handle increased ID cases. Hence, strengthening ID specialists and increasing hospitalists may be complementary approaches to dealing with emerging ID.

Hospitalists also have the potential to manage emerging ID, including COVID-19 and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) [Citation24]. Hospitalists had various, crucial roles in handling the COVID-19 pandemic in the US, such as frontline work in managing inpatient care, coordinating multidisciplinary teams, and collaborating with experts from various fields [Citation7]. This study also revealed that Japanese hospitalists were involved in various clinical settings associated with COVID-19, including inpatient care, emergency departments, and outpatient clinics, particularly in hospitals without ID specialists. One of the optimal strategies for COVID-19 care is hospitalists collaborating with specialists [Citation20]. However, in settings with limited or a lack of specialists, hospitalists may provide COVID-19 care independently. Furthermore, this study showed that hospitalists were involved in emergency care in hospitals without ID specialists. Numbers of emergency medicine specialists are limited in Japan, and so hospitalists may fill the gap when tackling future emerging ID [Citation13].

This study had some limitations. First, it may include a selection bias because the study subjects were chosen based on convenience sampling from the hospitalist information network rather than a comprehensive list of hospitalists in Japan. Therefore, it may be difficult to generalize the results to all Japanese hospitalists. However, there was a consistent trend whereby hospitalists were involved in various clinical settings in hospitals without ID specialists. Furthermore, we selected hospitals where a hospitalist division had been established and recognized as an independent division. Second, since we conducted this study involving academic community-based hospitals with five or more hospitalists and excluded university hospitals, the results may differ in non-teaching hospitals with only a few hospitalists or university hospitals. Therefore, the results of this study are only applicable to community-based hospitals with a sufficient number of hospitalists. Third, the fact that hospitalists were involved in various clinical settings in hospitals without ID specialists may be a simple reflection of a small-sized hospital. However, multivariate analysis showed a consistent association between the absence of ID specialists and hospitalists’ various work settings. This was a cross-sectional study, and additional cohort studies are needed to confirm whether ID specialists’ presence or absence was the driver of the diverse range of hospitalists’ work settings. Fourth, due to the low response rate, there may be a selection bias toward the hospitalists participating in this survey being more motivated for COVID-19 management than those who did not respond. Fifth, we did not collect information on the professional characteristics of hospitalists, such as their work schedules, infection rates, and deaths among those infected. Sixth, this study was conducted in the early stage of COVID-19 pandemic. The work style of hospitalists may be different between the early and late stage of the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, additional studies with a higher response rate are warranted.

Conclusion

In conclusion, hospitalists provided COVID-19 management in various clinical settings in the absence of ID specialists. However, the response rate of our study was very low and sample size was also deemed low. An additional large-scale study is needed.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

Toru Morikawa designed the study, the main conceptual ideas, and the proof outline. Toru Morikawa collected the data. Toru Morikawa, Taiju Miyagami, Masayuki Nogi, Toshio Naito aided in interpreting the results and worked on the manuscript. Toshio Naito supervised the project. Toru Morikawa wrote the manuscript with support from Taiju Miyagami and Masayuki Nogi. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (15.2 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate all hospitalists who participated in the study. The authors would also like to thank Dr. Eri Ishida for her grammar assistance. The concept of this study was presented at the 2021 Annual Meeting of the Japan Chapter of the American College of Physicians.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/21548331.2024.2337614

Additional information

Funding

References

- Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020 Apr 30;382(18):1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032

- Redberg RF, Katz M, Steinbrook R. Internal Medicine and COVID-19. JAMA. 2020 Sep 22;324(12):1135–1136. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.15145

- Wachter RM, Goldman L. Zero to 50,000 - the 20th anniversary of the hospitalist. N Engl J Med. 2016 Sep 15;375(11):1009–1011. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1607958

- Naito T. Will the introduction of the hospitalist system save Japan? Int Med. 2022; Sep 6. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.0693-22

- Yetmar ZA, Issa M, Munawar S, et al. Inpatient care of patients with COVID-19: a Guide for hospitalists. Am J Med. 2020 Sep;133(9):1019–1024.

- Keniston A, Patel V, McBeth L, et al. The impact of surge adaptations on hospitalist care teams during the COVID-19 pandemic utilizing a rapid qualitative analysis approach. Arch Public Health. 2022 Feb 17;80(1):57. doi: 10.1186/s13690-022-00804-7

- Bowden K, Burnham EL, Keniston A, et al. Harnessing the power of hospitalists in operational disaster planning: COVID-19. J Gen Intern Med. 2020 Sep;35(9):2732–2737. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-05952-6

- Morikawa T, Okada S, Nogi M. Hospitalists will play a central role in COVID-19 management. Reports from three medical institutions in Japan and the United States. Jpn J Gen Hosp Med (Japanese). 2020;16(2):252–257.

- Hamada O, Tsutsumi T, Imanaka Y. Efficiency of the Japanese hospitalist system for patients with urinary tract infection: a propensity-matched analysis. Intern Med. 2023 Sep 6;62(8):1131–1138.

- Hamada O, Tsutsumi T, Tsunemitsu A, et al. Impact of the hospitalist system in Japan on the quality of care and Healthcare Economics. Int Med. 2019;58(23):3385–3391. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.2872-19

- Kurihara M, Kamata K, Tokuda Y. Impact of the hospitalist system on inpatient mortality and length of hospital stay in a teaching hospital in Japan: a retrospective observational study. BMJ Open. 2022;12(4):e054246. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-054246

- Tago M, Watari T, Shikino K, et al. Five tips for becoming an ideal General hospitalist. Int J Gene Med. 2021;14:10417–10421. doi: 10.2147/ijgm.s341050

- Shimizu K, Hibino S, Biros MH, et al. Emergency medicine in Japan: past, present, and future. Int J Emerg Med. 2021;14(1). doi: 10.1186/s12245-020-00316-7

- McQuillen DP, Macintyre AT. The value that infectious diseases physicians bring to the healthcare system. J Infect Dis. 2017;216(suppl_5):S588–S593. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix326

- Dugdale CM, Turbett SE, McCluskey SM, et al. Outcomes from an infectious disease physician-guided evaluation of hospitalized persons under investigation for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) at a large US academic medical center. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2021;42(3):344–347. doi: 10.1017/ice.2020.434

- Hadano Y, Suyama A, Hijikata T, et al. The importance of infectious disease specialists consulting on a weekly basis in a Japanese tertiary care hospital: a retrospective observational study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2023 Jan 6;102(1):e32628. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000032628

- Matsunaga N, Hayakawa K, Asai Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of the first three waves of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Japan prior to the widespread use of vaccination: a nationwide observational study. Lancet Reg Health West Pac. 2022 May;22:100421. doi: 10.1016/j.lanwpc.2022.100421

- Tsuchiya K, Yamamoto N, Hosaka Y, et al. Molecular characterization of SARS-CoV-2 detected in Tokyo, Japan during five waves: identification of the amino acid substitutions associated with transmissibility and severity. Front Microbiol. 2022 Jul 27.;13:912061. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.912061

- Lee JH, Kim AJ, Kyong TY, et al. Evaluating the outcome of multi-morbid patients cared for by hospitalists: a report of integrated medical Model in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2019;34(25). doi: 10.3346/jkms.2019.34.e179

- McCarthy MW, Walsh TJ. The rise of hospitalists: an opportunity for infectious diseases investigators. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2018 May;16(5):385–389. doi: 10.1080/14787210.2018.1462158

- Hollingshead CM, Khazan AE, Franco JH, et al. Assessment for infectious diseases consultation in community hospitals. Infect dis ther. 2023 Jun;12(6):1725–1737. doi: 10.1007/s40121-023-00810-4.

- Zahn M, Adalja AA, Auwaerter PG, et al. Infectious diseases physicians: improving and protecting the public’s health: why equitable compensation is critical. Clin Infect Dis. 2019 Jul 2;69(2):352–356. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy888

- Hagiya H, Otsuka Y, Tokumasu K, et al. Interest in infectious diseases specialty among Japanese medical students amidst the COVID-19 pandemic: a web-based, cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2022;17(4):e0267587. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0267587

- Yang Y, Peng F, Wang R, et al. The deadly coronaviruses: the 2003 SARS pandemic and the 2020 novel coronavirus epidemic in China. J Autoimmun. 2020;109:102434. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2020.102434