ABSTRACT

The personal and community identity of many areas of greater Europe has been interwoven with religious practice, with the ringing of church bells often dictating the quotidian rhythms of life. The symbolism of churches and church bells can be likened to that of monuments, with the erection of bell towers and the installation of bells engendering certain political powers, both in the secular and sacred realm. Just as the creation of an auditory marker can be deemed a political tool, the cessation or absence of this marker can be similarly considered political in nature. This document will examine the termination of bells and bell ringing as an exercise of political power either as symbolic acts of conquest or through purely utilitarian reasons, and consider the restitution of bells as a further symbolic exercise of political power by the victors and an act of contrition by the vanquished. Finally, it will discuss how the historical imposition of the silencing of meaningful sounds may have heritage implications in the modern world.

1. Introduction

Religion has been entwined with personal and community identity in many areas of Europe (Byrnes and Katzenstein Citation2006), with the church being the focus of a community and the ringing of church bells dictating the quotidian rhythms of life (Corbin Citation1998). While the church itself has symbolic power, in many denominations the bell is a physical and auditory representation of the voice of God (Burnett Citation2002). The symbolism of a church and church bells can be likened to the symbolism of monuments, with certain powers being bestowed on these objects and their erectors. From the nineteenth century, monuments developed essentially into visible manifestations of bourgeois political culture – a representation of community identity particulars having social, cultural and political basis (Michalski Citation2013). Like monuments in the political sphere (statues, obelisks, etc.), it can be argued that the erection of bell towers and the installation of bells can engender certain political powers, both in the secular and sacred realm. Even so, the sounds of bells are audible markers of a community, dictating the realms of community space and place (della Dora Citation2021) with the sound carrying further than line of sight (Wood Citation2013). Thus the notion of the symbolic nature of the bell is not limited to the visual distance of the object, but rather to the end of the signaling presence; i.e., to the outer limits of the audible range. Just as the creation (both the installation and the actual ringing) of an auditory marker can be deemed a political tool, the cessation or absence of this marker can be similarly considered political in nature. Enforced silence of any community-accepted sounds inhibits everyday societal function and living culture. In this way, cessation of bell sounds can act as a political dynamic in an attempt to control portions of (or the entire) society, and in doing so can fracture social stability, forcing a degree of dominance through governance of the aural realm.

In some instances, politically motivated provisioned bells attained lasting significance in the secular realm. Such examples include the Liberty Bell (Philadelphia, USA), which has now acquired iconic status as the symbol of U.S. independence (Nash Citation2010); the Olympiaglocke (Olympic bell), the official symbol of the Berlin Olympics and a potent political tool for the National Socialist Party of the time due to its inscriptions, swastikas and nationalistic icons (Rombouts Citation2014); the Freiheitsglocke (Freedom Bell) of West-Berlin, being an audible symbol in the struggle between the capitalist “free” West and the communist “oppressed” East (Daum and Liebau Citation2000); and the great bell of 1655 Grigor’ev’s of the Kremlin, which served both the Orthodox Church and the political state, with divergent decorative inscriptions of the tsar and tsarina, alongside relief icons of Jesus Christ to make this notion clear (Williams Citation2014).

Given such examples of the provisioning of bells as symbols of political will and power, it is not surprising then, that destruction and restitution of bells were similarly widespread political symbolic acts. While previous research has investigated examples of the requisition of bells during World War I (Morelon Citation2019), World War II (Freeman Citation2008; Shapreau Citation2019), and nineteenth-century France (Corbin Citation1998), in the following discussion, the focus of examination will be on the termination of bells and bell ringing as an operational exercise of political power. The destruction and silencing of the bells are manifestations of a political exercise, whether for ideological reasons, as symbolic acts of conquest or for purely utilitarian reasons. These various manifestations are often intertwined, for example where primarily utilitarian reasons for the removal of bells for raw material acquisition manifest themselves at the local level with strong ideological overtones. This document will first present a short discussion of research covering politics of the aural dimension, before exploring the destruction of European bells (covering geographical areas of eastern, central and western Europe as well as the geographically European areas of Russia and Turkey), both pre- and during the twentieth century as an exercise of both overt and latent political power. The paper concludes by considering the restitution of bells as a symbolic exercise of political power by the victors and an act of contrition by the vanquished, before extending the scholarly discussion of the politicization of the aural dimension by considering how such meaningful sounds fit into the soundscape of a place, and how emotionally attached sounds may be considered as intangible forms of heritage.

2. The Politics of Sound

The acoustic environment of any location or place contributes to a unique soundscape, which is perceived and experienced by members of the community within a social context (ISO Citation2014). Whilst soundscapes can include any indoor or outdoor space, religious sounds and soundscapes have been previously investigated across a similar range of religious spaces, such as Buddhist temples, Shinto shrines, and historic mosques (Lee, Lim, and Garg Citation2019; Yilmazer and Acun Citation2018; Zhang et al. Citation2018), focussing on religion-specific sounds such as the ringing of church bells and calls to prayer (Hynson Citation2021; Kiser and Lubman Citation2008).

Furthermore, scholarship has investigated the contested nature of competing sounds within the aural realm; given that sound spreads over space and can shape an area’s character, control over an aurally defined realm (soundscape) can be viewed as a symbol of political dominance over a given region (Schwarz Citation2014). Such contested aural spaces include Jewish/Arabic spaces of Jerusalem (Schwarz Citation2014; Wood Citation2015), Islamic/non-Islamic city spaces in Europe (Leone Citation2016), and soundscapes of Islamic populism in Turkey in protest against an attempted coup (Basdurak Citation2020). Contested aural spaces also include perceived encroachment of Christian religious sounds into non-religious (public) spaces (Leone Citation2016), with the effective power of these sounds often being exercised at the local clergy level, despite the sounds emanating community-wide (Spennemann and Parker Citation2022b). Such conflicts with religious dimensions are often entwined with the aural dimensions of proclamations of faith, such as through the amendment of an Israeli environmental law limiting the use of public address systems from a residential prayer house to between 7:00am and 11:00pm; which principally affected the muezzin’s call for prayer and caused a degree of depersonalization of people of the Muslim faith (Efron et al. Citation2020). It is evident through the literature discussed above that contested spaces (and therefore political control) of the aural realm can be apparent at multiple scales (local, city-wide, country), with political actors comprising individuals, government bodies and regimes. It is through this lens of political control of an area’s sounds and soundscape that this paper will investigate the destruction of European bells, both pre- and during the twentieth century as an exercise of both overt and latent political power.

3. Destruction of Bells as an Exercise of Political Power Pre-twentieth Century

There is a long history of political power being manifested through the requisition and destruction of church bells, and many cases evidence this. In 1230, for example, the Archbishop of Mayence (Mainz, Germany) levied a crusade tax on the town of Erfurt, demanding the surrender of each church bell, or payment in lieu of the bell (Schmidt Citation1986). In 1414 Margrave Frederick I of Brandenburg reputedly confiscated the bells of the Marienkirche in Berlin to cast cannons (Sartori Citation1932, 37). During the Peasants’ War (‘Bauernkrieg) of 1525, when church bells were widely and systematically used as signaling devices, numerous churches were raided for their bells, both to silence them and to melt them down to make weaponry (Stockmann Citation1974).

Turkish forces, upon capturing Constantinople in 1453, were the first to set the example of the breaking of the bells. During the battle, the church bells of the city were rung continuously by emperor Constantine XI Palaeologus to inspire his people with the hope of God in the face of battle until the city was captured. Upon Constantinople’s capture, Mehmed the Conqueror permitted the continuation of Christian church and burial practices, but a treaty was signed which agreed upon banning the ringing of the bells; making them effectively prisoners of war (Williams Citation2014). This proscription created a four-hundred-year “aural vacuum” in the city which was lamented by Western travelers until 1856 when the ban was lifted (Williams Citation2014). The change of soundscape from the melee of bell ringing to silence is a poignant example of ideological power through bell destruction in the Middle Ages, particularly in light of the fact that the associated Christian religion was allowed to continue under the rule of the Ottomans.

A similarly early record of the requisition of a bell epitomizes the latent political power of such action. In 1478 Ivan III had subdued the city of Novgorod, coercing this successful market center to concede the authority of Moscow. In doing so, Ivan III seized the most important bell of the center which had both practical and historical association. This “veche” bell had been rung to both call Novgorod town assembly and to proclaim the town’s independence. By abducting and transporting this bell to Moscow, he had effectively both imprisoned the bell and had silenced one of the few remaining symbols of oligarchical rule in Russia (Williams Citation2014).

Later centuries saw similar episodes. During the thirty-year war of 1615–1645 which engulfed much of Central Europe, churches were deemed primary targets as they were visible symbols, and tangible manifestations of opposing denominations (Mitchell Citation1840, 142). In particular, Protestant (Swedish) forces raided Catholic churches for their bells (Saam, Citationn.d.). General Wallenstein, leader of the Imperial Army, reputedly ordered the melting down of church bells in Bohemia to source metal to successfully re-establish an artillery division for the Thirty Years War (1615–1645) (Mitchell Citation1840, 317).

Similarly, following his defeat in the Battle of Narva (1700) and the associated loss of much of his artillery, Czar Peter the Great confiscated almost 100,000 church bells in his realm in order to have new cannons cast (Duffy Citation1981, 17). The Turkish occupation of parts of Austria during the wars 1529 and 1682 led to the widespread removal of bells, so much so that pre-eighteenth-century bells are disproportionally rare in these regions (Baier Citation2013).

The symbolic destruction of a single bell is perhaps best epitomized during sixteenth-century Russia, where a 704-pound bell from Uglich was flogged 120 times, had its “tongue” and “ears” removed, and was banished to Siberia after it had dared to sound the call for a local uprising (Williams Citation2014). The symbolism of capturing a bell as a sign of conquering one’s foe is evident, particularly so in Russia where bells are considered as animate beings in Russian folklore, where they “exercise a profound power over humankind” (Batuman Citation2009). The control of a bell can therefore be seen as a symbol of power over the people, their way of life and their quotidian rhythm, reflecting other European superstitions and belief practices.

The historic destruction of bells hit its zenith during the French Revolution and presents a good case for this activity as a symbol of ideological power. Even though the Catholic religion in France did not play the same central role as for example, in Italy, church bells were a ubiquitous, audible manifestation of the traditional and privileged power structure. Bells, described as “noisy, sleep-depriving nuisances” (Falaky Citation2020), came under scrutiny even during the pre-revolutionary period but became a specific target during the French Revolution. It was instigated when the National Assembly passed legislation in November 1789, placing all church property at the disposal of the state (Louis XVIII Citation1789), with numerous pamphlets arguing that this freed up bells as ready sources of bronze suitable for other purposes (Boucault Citation1790; Gaucher Citation1790; Mittié Citation1789). A shortage of raw material for coinage in June 1790 led to a formal assessment whether bell bronze was suitable, without separation into its constituent elements, as such raw material (Dewamin Citation1895, 3). A decree in April 1792 made it legal for abandoned bells to be confiscated and melted down for coinage (Assemblée nationale Citation1792) with the Municipality of Paris for example, ordering that only two bells were allowed to be retained by each parish. This became a nationwide law on August 17, 1792 (Clay Citation2012). In July 1793, during the period of forced de-Christianization, which culminated in the Terror period (autumn 1793–July 1794), functioning churches were allowed to retain a single bell, with the rest to be delivered within a month to a depot for melting down for use in cannons (Convention National Citation1793, 173). This declaration was followed by the demolition of the bell towers (decree of January 26, 1794) as visible symbols of the Catholic church, dominating the roof tops of French communities. On February 21, 1795, all bell ringing as an outward symbol of religion was prohibited (Falaky Citation2020), which dramatically changed the soundscape of all communities, but no more so than that of Paris (Clay Citation2012). By May 21, 1795, the Municipality of Paris decreed that all bells be taken to the foundry for conversion into cannons, except for bells that would be needed for non-ritualistic, community signaling (Magne Citation1904, 105ff.).

Against the background of anti-Christian sentiment, the episode of the French Revolution shows the significance of both attributes of bells, their ritual, symbolic power which had to be suppressed, and their prosaic use as signaling devices. Although invisible when mounted in the church towers, bells were audible, and through their pattern of ringing created a soundscape that was ritualistic or mundane. Critically, signaling only required a single bell, preferably of a high pitch that insinuated urgency, while ritual bells relied on lower pitches, generating more contemplative sound marks. From a material perspective, it was beneficial that the higher pitched bells were small, thus freeing up large quantities of bell metal. While most communities complied with the various orders of bell collection (Destainville Citation1920), large numbers of historic bells were hidden by the congregations, in particular in smaller communities, either buried in the ground or inside private buildings, or abducted by the community whilst in transit for acquisition (Corbin Citation1998). During the French Revolution, about 100,000 bells were removed from the sixty thousand towers (Corbin Citation1998), leaving France with less than 10,000 pre-Revolution bells remaining (Kramer Citation2007, 105ff). Bells that were too large to be lowered, were broken up in situ, and reputedly eight men worked for six weeks to break up the second largest bell hung in Notre Dame in Paris (Saam, Citationn.d.).

4. Destruction of Bells as an Exercise of Political Power in the Twentieth Century

4.1. Raw Material Collection of Bells During World War I

A material shortage throughout many continental European countries during World War I instigated collection programs, which often involved the requisition of church bells. While during World War I cannon barrels were no longer made from bronze, the armament industry required large quantities of copper and tin for gun steel (10% tin), breech blocks (bronze), shell casings and grenade rings (both brass). Thus bells were seen as a strategic raw material reserve. Quite early in the war, in February 1915, the German war ministry carried out an audit of bells in church towers in order to approximate the volume of copper alloys that might be requisitioned (Saam, Citationn.d.). As the war progressed, and Germany and Austria experienced raw material shortages, the war ministry ordered in March 1917 the collection of all bells with the exception of bells below 25 cm diameter, with the metal of these bells required for the railways and for shipping. Exempt were also bells of “special artistic or historic value” as determined by the national monuments office (“Staatsdenkmalamt”) (Georgi Citation1917, §2). The subsequent regulations classified all bells into three Groups (A–C), whereby bells of Group C possessed high scientific or historic or artistic value as determined and certified by an expert. Bells of group B possessed high scientific or historic or artistic value, or potentially possessed high cultural value but had not yet been certified as belong to group C. Also classed as Group B were single bells required as notification devices, whereby the bell with the lowest weight was retained in the tower (Levacher Citation1917). All others could be requisitioned. By and large, while bells older than 1860 were retained (Finke Citation1957), some 65,000 bells with a combined weight in excess of 21,000 tons were collected in Germany (and Austria) and melted down (Schilling Citation1954).

Even though the demand for bronze alloys for the war effort was great, the destruction of bells within the borders of Imperial Germany was not indiscriminate, as is obvious in the case for Bavaria (). There, with the exception of one subregion (Palatinate/Pfalz) between 32.1% and 40.9% of all bells were classed as able to be requisitioned, while between 27% and 39% retained for their cultural value. Only 1770 were saved (Vogel Citation2009). Similar processes played out to various degrees in Austria (Schubert-Soldern Citation1919), in the formerly French territories of Alsace and Lorraine which had annexed by Prussia in 1871, and in the territories occupied by German forces during World War I (see below).

Table 1. Requisition of church bells with a diameter greater than 20 cm. Data for Bavaria April 1918 (in proportion of classification). Raw data after Braun (Citation1990).

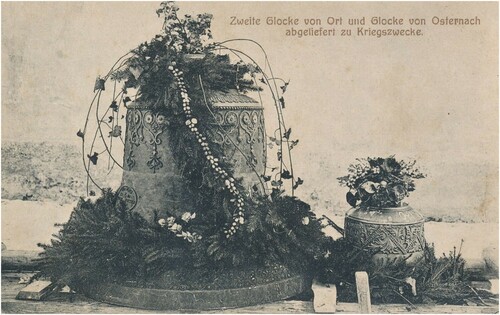

While the parishes had to accept the fate of their bells, the way they parted with them demonstrated the importance of the bells to the community. They demonstrated their close attachment not only attending their last ringing during service, but also by watching them being lowered down, and respectfully placing them, decorated with flowers and garlands, on the wagons that took them away (). These demonstrations show the great love of the general populace toward both the physical object and the sound produced by tolling, and it gives an indication of the deep impact bell requisition would have had on the community.

4.2. Destruction of Bells in the USSR in Inter-war Periods

Similarly, the destruction of bells within the USSR in the mid-twentieth century can be viewed as a symbolic activity of ideological dominance. With the rise of communist power in Russia in 1917, the basic Communist doctrine of militant atheism led to a decree on January 23, 1918 which separated Church from state, secularized education, and dispossessed all church property (Timasheff Citation1941). A further decree from February 26, 1922 ordered the surrender of all church articles of gold, silver and precious stones – a ruling that was vehemently opposed by the leader of the Russian Orthodox Church, arguing that it was canonically impossible to relinquish sacred objects (Batuman Citation2009). The government policy formed in 1929–1930 to destroy religion by undertaking a mass closure of churches, the burning of ikons and the silencing and then removal of church bells, could then, by extension, be understood as the destruction of not only the structural centers of the church, but as a targeted obliteration of the visual and aural icons so embedded in religion; as Orthodox Church bells operate both as the symbol of the trumpet calls blown on Mt. Sinai and for the raising of the dead before the Last Judgment, and not as a musical instrument, but as an icon of the voice of God (Batuman Citation2009; Williams Citation2014). Up to World War II, the Soviet destruction of bells was colossal: of the thousands of sets of bells in the approximately 50,000–70,000 churches and monasteries in the state (almost to a million bells in total), as few as four sets survived, with one, the set from the Danilov monastery surviving purely from its removal to the United States as scrap metal by an American philanthropist (Ireland Citation2008; McGuire Citation1997). Estimates suggest that 99% of all Russian bells were destroyed by the Soviets, with bells often removed from the towers of churches left standing, then melted down and reappropriated to provide metal for industrial and agricultural products (Vladykin Citation2002) – a symbol reflecting the political ideology of the greater level of importance placed on work, rather than religion to the people living under Communist rule.

Whilst the destruction of bells is a political and ideological tool, the Soviets followed through this anti-religious campaign with blood; only a few thousand of the estimated 200,000 Russian Orthodox clergy survived to see the stirrings of World War II and the shift of the Soviet government’s doctrine in August 1941; asking for the “Russian Orthodox Church to reassume her responsibilities for the consolidation of the Orthodox Russians in the fight against the Nazi invaders,” a call for the inhabitants of the occupied countries to rise in defence against the German regime for their own religious freedom (Ireland Citation2008; Kalkandjieva Citation2014; Timasheff Citation1941). Despite Stalin wielding controlled religion as a weapon against the invading forces of Germany, the use of pealing bells as a political tool could not happen here as most of them had previously been destroyed.

4.3. Raw Material Collection of Bells During World War II

The magnitude of metals acquired by prize reached another peak in World War II, again by German military and civilian forces. In a replay of World War I, Allied naval blockades strangled German supply lines for raw materials needed by the armaments industry, causing bells to again be regarded as a strategic raw material reserve. Once hostilities of World War II arose, the Reichsstelle für Eisen and Metalle concluded that the reappropriation of bells would be the easiest solution to obtain sufficient quantities of sought-after metals such as copper and tin, and engaged a requisition order on March 20, 1940 in order to enable this (Anonymous Citation1940a; Price Citation1948b). First discussions were undertaken at Easter in 1940, with all bells being classified into four groups according to their value: ranging from Group A (the least valuable bells, all cast since 1918) to Group D (the most valuable, including bells from the middle ages and non-modern carillons) (Mahrenholz Citation1952; Price Citation1948b). Despite the earlier opinion of Göring that only 100 bells needed to remain across Germany, one bell was allowed to remain in each parish church (the most valuable bell) (Price Citation1948b). Congregations were allowed to retain this single calling bell (“Läuteglocke”), provided it did not weigh more than 25 kg, which were less than 3% of the total bell stock (Mahrenholz Citation1952). Overall, almost 95% of all German bells were removed from their structures, and by the end of the war, the majority of Group A bells had been melted down, leaving Group B and C bells largely untouched in seven depositories around the country (Price Citation1948b).

Across Europe, Germany is exemplified here as the country with both the highest number and highest proportion of bells removed during World War II. However, German forces were initially met with internal resistance; both Catholic and Protestant church leaders offered significant protest against the removal of their bells, until a resigned disposition overtook them with the common words of “the terror was too great” (Price Citation1948a). The high level of removal and destruction of German bells is itself political in nature, and one that ascribes to the Nazi ideology of Christianity being an alternative view “incompatible with National Socialist Ideology and an obstacle of its realisation of its tenets” (Bendersky Citation2013). Control of the church bells is a symbol of having control over the church itself (of any denomination), and a blow to those who attempt to evade the restrictions of Christianity in public practice.

4.4. Destruction of Bells Contrary to The Hague Convention

The twentieth century saw for the first time an overarching protection of church bells in conflict periods and across contested areas. The introduction of Convention respecting the laws and customs of war on land of 1907 (“Hague Convention”) challenged the historical approach to bell reappropriation both during and after military conflict, with Article 56 stating that:

[t]he property of municipalities, that of institutions dedicated to religion, charity and education, the arts and sciences, even when State property, shall be treated as private property. All seizure of, destruction or wilfull damage done to institutions of this character, historic monuments, works of art and science, is forbidden, and should be made the subject of legal proceedings. (Bevans Citation1969, 653)

Contrary to The Hague Convention 1907, German forces undertook both seizure and destruction of bells and other cultural property across occupied territories in Europe in both World Wars. However, the method of removal and subsequent melting down of bells by Nazi Germany during their European occupation was non-uniform across these countries, with decisions being either overtly political, or having undertones of political belligerence. It was not simply the case of “one rule for us and one for them”; decisions by the Reich on the intensity of bell destruction were based on pre-War and contemporary political ideologies as evidenced in the following examples.

With the Treaty on the protective relationship between Germany and the Slovak State being formed in March 1939, the newly formed (First) Slovak Republic was placed under the political and economic protection of the Third Reich (Lumans Citation1982), with this protection continuing into the decision to limit the number of bells taken from this state. Despite a 1940 German order to undertake a bell inventory of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, Slovakia was not initially included (Price Citation1948b). Once completed, the first procedure was to remove bells with Czech inscriptions from towers in the Sudetenland (an area with a high number of ethnic Germans), and then to systematically remove the majority of the remaining bells from this Protectorate based on a devised classification with relevance to the bell’s age (Price Citation1948b). Despite one bell being able to remain in each parish church, around 84% of bells and all bells from Group A (post-1917) had been removed from the towers in the regions of Bohemia and Moravia (Price Citation1948b). It was not until 1944 that bells were finally sourced from Slovakia, owing to the growing demand on metallic resources. This four-year hiatus to include Slovakia as a source of bells for removal and destruction is political in nature, and can be explained by the close links that Slovakia shared with Germany, such as the Treaty above and the obedient collaboration by the Slovak Republic in both the invasions of Poland and of the Soviet Union (Weinberg Citation1994). Converse links exist within the areas of the Protectorate, with Hitler’s ideology of the Slavic Czechs as an inferior race who required cultural and physical annihilation, and a desire for the dismantlement of the state of Czechoslovakia with the subsequent release of Czech Germans from (incorrectly alleged) government persecution (Kalkandjieva Citation2014; Lumans Citation1982). Statistics support these ideologies (), with a high number of Czechoslovakian bells removed during the war (80%), and a very high proportion of those bells destroyed (95.3%) – the highest proportion across any country in Europe, and this is further evidenced by the decision to initially remove Czech inscribed bells.

Table 2. The removal of bells across Europe by German forces in World War II (Data source: Price Citation1948b).

Many churches at local and national level implored the government to save the church bells from destruction, in particular since many congregations had lost their bells in World War I and had only been able to replace them in the intervening two decades, often with great difficulty and at great cost. Driven by antireligious ideology, the Nazis remained unbending in their demand for church bells (Mahrenholz Citation1952). Administratively, the authorities further reduced any retention of bells by regulating that only formally incorporated and legally independent congregations could retain bells and that in the event of future changes to the ruling, the congregation had to wear the costs of taking down a calling bell that it was hitherto permitted to retain (Mahrenholz Citation1952). Exemptions from destruction were to be afforded to bells that had historic or artistic value and had been cast before 1860. Church authorities were made responsible for the self-assessment of each bell with all bells to be saved subject to an independent approval by state heritage conservators. As the program continued, some bells were taken, subject to further assessment and classification. Many of these were unilaterally re-classified as insignificant and melted down, without consultation of either church or heritage authorities. As Mahrenholz (Citation1952) noted, by involving them in the progress, many congregations were made complicit in the sanctioned destruction. Regional differences emerged, subject to the extent to which the congregations or dioceses subscribed to the nationalistic ideal. In the dioceses of Fulda, Speyer and Vechta, for example, medieval bells as old as the thirteenth century were offered for scrap metal irrespective of heritage concerns (Mahrenholz Citation1952).

Similar to World War I, the German political symbolism of the requisition of bells was continued in the Alsace-Lorraine region in World War II. The Pétain headed Vichy government of France, had argued that the Nazi removal and destruction of French bells would constitute an attack on the national heritage of the country, and would furthermore be a violation on the Franco-German Armistice agreed to in the previous year. Such was the fervency of the French objection to protect their heritage, it was concluded that the commandeering of church bells would result in vehement local opposition and other processes would need to be implemented (Shapreau Citation2019). Proposals were brought forward in July 1941 to acquiesce to German demands for non-ferrous metal through the procurement of public statues (Freeman Citation2008). Thus, the bells of France were mostly saved, presenting an interesting notion of “protected” bells being a symbolic and political concept of a nation’s legacy and heritage, with the Vichy government being allowed to continue to benefit from the support from the successful Church of France (Richard Citation2012). However, the German-annexed areas of Alsace-Lorraine were not under the protection of the Armistice agreement. Here, 2,000 Alsatian and 932 Lorraine bells were requisitioned under the orders of the Reichsstelle für Eisen and Metalle, Berlin, with the removal of these bells sending a broad political message that this region was again under government control of Germany (Price Citation1948b). It is interesting to note that politics again make a fundamental difference in the number of bells destroyed in each of these regions. Whilst 87% of bells removed from Lorraine were actually destroyed, the corresponding figure from Alsace is only 40% and can be reasonably explained by the higher proportion of German-based dialects in the Alsatian regions (Dehdari and Gehring Citation2019). This difference either presents an appeasing to the German-based dialect regions, or a damning of the French-based dialect regions, and either way the difference in proportion is political in nature.

Bells were also requisitioned from Poland, and despite the lower proportion of Polish bells being removed by German forces (around 70%), almost 93% of these bells were subsequently destroyed or melted down (). This can be attributed to the manner in which many bells were destroyed, as written so solemnly by Price in 1948:

On the ground under an eighty-foot derrick stands a bell of magnificent proportions. In relief on the side is the figure of a Madonna, under which is the inscription “Queen of the Polish Crown, Pray for us”. Above this bell, the full eighty feet, another bell of similar size is raised and then dropped on to it. The dropped bell is broken into fragments, which fly in all directions … The process is repeated monotonously as each bell, with one last soul-piecing cry, is demolished. Gradually the bell receiving the blows is scarred, the Madonna is partially chipped away, the inscription becomes illegible. Finally it too breaks apart and falls inward on the ground in a number of pieces. Another Polish bell is put in place. The process goes on. (Price Citation1948a, 15)

During this period of war, almost 150,000 individual bells were procured from European countries by Nazi Germany () (Freeman Citation2008). Of these bells, around 90,000 were taken from within Germany, with the remainder being taken in occupied countries, such as Czechoslovakia, Poland, Netherlands and Belgium (Price Citation1948b). Whilst other cultural items were looted because of aesthetic motives, and bells being collected for their metal content (Shapreau Citation2019), the efforts of German forces to source bells from both within the Reich and from occupied countries can also be seen as a manifestation of political motives; bells not only changed the European soundscape with the emergence of silence rather than the tolling of bells, but the removal of an item so engrained in both religious and community ritual has itself a certain degree of political power. Certainly, the motives of Nazi Germany echo the earlier Soviet campaign against religion, with the leader of the Soviet Young Communist League highlighting the similarities between the Soviet and Nazi states after a meeting with Hitler, explaining that “both groups opposed the Christian ideology and that the Catholic clergy was their foremost common enemy” (Timasheff Citation1941).

5. Restitution of Bells as an Exercise of Political Power

Just as the requisition of bells can be a symbol of political oppression by an invading or occupying force, the restitution of stolen bells can be viewed as just as powerful. Following Germany’s defeat in World War I, great efforts were made to locate and repatriate the bell of a church in Marquillies (Dept du Nord, France) which had been captured by German forces in 1914. Because of its political inscription mourning the French loss of Alsace-Lorraine in the Prussian war of 1870, this bell was rung on the occasion of major German battle victories and defaced by German inscriptions commemorating these. Taken as a war trophy to Berlin where it was displayed in the armory 1916, the bell was eventually returned to Marquillies in 1919 (Spennemann and Parker Citation2022a).

In wartime setting, the ringing of French church bells was often viewed not only religiously, but politically. In the village of Thionville, after six months of silence, the sonorous church bell pealing for Easter celebrations on March 24, 1940 echoed both the resurrection of Christ, and a resurrection of faith for the rightful defenders of justice to return France to its people, and a return of normal life of peace and calm to this village and all the surrounding towns (Anonymous Citation1940b). Furthermore, it was commented that the ringing of bells affected the community directly, with the sound allowing them to straighten their backs and walk with a more reassuring aura (Anonymous Citation1940b). In short, the return of the sound of bells inspired the people to continue life wishing for the best. It follows that if any requisitioned bells were returned to a town or village, this sense of candor and liberty would return on an even greater scale.

The demand for proper bell restitution is evidenced by events across Italy, which removed and surrendered their own bells as an offering to the German regime. Subsequent inappropriate measures to “fill the vacuum of sound” were not accepted and the original bells and sounds were solely missed:

Ersatz Bells in Italy. – According to a report from Zurich, the Italian government is offering the churches of Italy gramophone records of chimes to be broadcast by means of loudspeakers from the steeples in place of the bells which have been taken for scrap metal. This has caused great dissatisfaction among the clergy and people, and the Archbishop of Milan has forbidden their use in his diocese. (Anonymous Citation1942)

5.1. Replacement of Destroyed Bells by the Local Congregation

The return of stolen bells from World War II was already widely celebrated by 1946. With the repatriation of bells to Belgian towns immediately after the end of the war, verbal reports and photographic documentation were given to Price showing the enthusiastic celebrations and festivities undertaken by locals across many towns and villages upon the bells’ return. In some places, processions escorting the repatriated bells from arrival place to the bell towers from which they were removed during the war, and similar festivities were recorded in areas of Lorraine, France (Price Citation1948b). Here as early as August 1945, communities welcomed back the bells to small number of churches in the Metz Chateau-Salins and Dieuze regions. These bells, stolen by “vultures from beyond the Rhine” and subsequently stored in Regensburg, were welcomed by a Bishop at the foot of one cathedral with such emotion that no other news could please the people during those memorable days of post-War renewal (Anonymous Citation1945).

In Belgium, to celebrate the survival of the 727 bells after the war, and the return of those originally sent to Hamburg for destruction (), ceremonies were organized in Antwerp on October 8, 1945 and November 5, 1945, in Liège (Merland Citation2012). Commanding the attendance of military, government and religious authorities, and with speeches made by Colonel Joseph de Beer, president of the Commission for the Protection of Bells in Belgium, the bells were finally returned to parishes from whence they were taken. It must have been particularly satisfying for de Beer to address such a ceremony, as heavily involved in the Belgian Resistance, he vehemently opposed the requisition of the country’s bells, and through non-violent means instigated obstacles in an attempt to inhibit this action, such as supplying falsified documentation, concealment of bells, the sabotage of removal equipment, and the interception of bells in transit to Germany (Merland Citation2012).

Figure 2. Hamburg, Freihafen – Glocken auf einem Kai lagernd (“Glockenfriedhof)” [Bells stored on a quay “bell cemetery”]; 1947.

Source: Unknown photographer, Bundesarchiv Bild 183-2007-0705-501.

![Figure 2. Hamburg, Freihafen – Glocken auf einem Kai lagernd (“Glockenfriedhof)” [Bells stored on a quay “bell cemetery”]; 1947.Source: Unknown photographer, Bundesarchiv Bild 183-2007-0705-501.](/cms/asset/f496c06e-fb39-4f98-bfca-e7d37ce87f51/yhso_a_2330337_f0002_ob.jpg)

The strength of restitution and subsequent ringing of bells can clearly be perceived in modern Russia. In 1992, a marathon peal of bell ringing was directed from the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour – a church built on the site of a cathedral demolished by Stalin, with the repaired bells ringing for the first time in Easter since the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution (McGuire Citation1997). The sound of the bells ringing in these circumstances symbolize the “joy of victory over the cruel commissars who waged a war against religion” and speak of moral and political vindication (McGuire Citation1997). The restitution of the bells helped to bring right to wrongs of the past, and was a powerful political tool for the community to counteract some of the extreme oppression since the 1920s – a defiant aural blow to the previous silence of bells of the previous 75 years caused by prohibition of bell ringing and the physical destruction of the church.

The active restitution of stolen bells is still of present concern. As late as December 2020, Polish bells appropriated by the Nazis were being repatriated to their homeland. One bell which dates back to 1555, originally located in St Catherine’s church in Sławięcice (southern Poland) was tracked down to Münster, Germany, by the Polish church’s pastor (BBC News Citation2020). Having not been melted down by German forces, and banned from its return to the east by British military authorities, it was instead loaned out to church parishes in former West Germany, whence is rested for many decades in a courtyard of the city’s Catholic Church (BBC News Citation2020). Once sent home to Poland, it was still officially on permanent loan as it was technically still owned by the German government, which raises complicated questions on ownership of history and heritage with reference to repatriated church bells.

It must be noted that in the post-World War II period British forces undertook some active denial of restitution toward bells which originated in Germany. Following the surrender of Germany and the subsequent part occupation by the British, the Office of Monuments, Fine Arts and Archives (MFA&A) who administered bells in the British Zone, decreed that all German bells located in depositories declared be seized pending further action, despite being in variance with the policy in the U.S. Zone (Price Citation1948b). Subsequent German requests for the return of bells in the British Zone were met with vehement denials, remarking that no German bell was to be remitted until the many thousands of stolen bells were returned to the Allied countries first. And salient to the political latency of removing bells, the MFA&A remarked:

All of the rest of Europe the church towers are now silent as a result of your nation’s vandalism. Yet in Germany itself one bell remains in every church. … The partial silence of your own church tower may usefully serve as a reminder to the parishioners and yourself of your own personal guilt. (Price Citation1948b)

6. Discussion: Aural Heritage and Politics of Sound

The silencing of bells as a political tool is perhaps most obviously seen in reverse, whereby bells are rung in celebration for national or global political events. The pealing of the bells at the conclusion of both World Wars “rings true” this sentiment. Local tradition reports that the bell Gabrielle, dated from 1560 and located in the region Champignelles, actually split open on November 12, 1918 as a result of its continuous celebratory ringing for two whole days to support the conclusion of the war (Richard Citation2012). However, as the above discussion shows, the destruction and silencing of bells has strong and somewhat latent political undertones comparable to more recent conflicts with religious dimensions as identified earlier. The destruction of, and forced cessation of a sounding bell is shown to be a manifestation of political power, that acts to control society through governance of the aural realm.

The historical destruction of bells by a power and subsequent enforced silence on the community has pertinent heritage implications twofold; firstly, of issues pertaining to actual damage, injury or removal of a physical heritage item by an authority or other agitated groups, and secondly, of issues concerning the imposed silencing of sounds which have perceived value by a community.

The first issue has largely been discussed in both the literature and media, as it is quite prevalent in our current world (Akramy and Hakim Citation2021; Diaz et al. Citation2020). The second issue pertaining to heritage has not been widely discussed and has been largely ignored to date. Drawing on the German term Kirchspiel, whereby a parish’s boundary is delineated by the sound of the parish’s church bells, any emanated sound affects any person in the aural realm of hearing. Thus, any silence of these sounds similarly affects people across the same area. Ultimately, this “community of listeners” are subjected to these sounds whether they like it or not. The historic examples show that authority figures removed bells both for resources for weaponry and as a political tool to control the people through enforced silence. The symbolism of silencing daily auditory routines manifested political power on a daily basis without the need of a show of force. The examples of restitution and celebratory bellringing discussed earlier demonstrates the importance of the return of not only the bell itself, but, more significantly, the return of the sound – which was missed dearly during periods of silence. Similar to the implementation of the “Muezzin’s Law” of Israel or the restrictions imposed on religious processions in Singapore (Efron et al. Citation2020; Kong Citation2005), the resultant termination or reduction of aural markers with an emotional (or spiritual) attachment may have serious implications, both for loss of the sounds themselves as they may act as important soundmarks in the soundscape (Engel and Fiebig Citation2022), and the concomitant loss of these sounds to society.

Some sounds evidently have a high degree of bestowed value by sections of the community and can therefore be recognized as a form of heritage (Parker and Spennemann Citation2022). While such sounds and soundscapes with bestowed value are identified as intangible heritage, they need to be systematically collected over different temporal periods to record not only the sonic cultural heritage dimension but also how these acoustic markers transform over time (Yelmi Citation2016). This may be of vital importance when an element of a soundscape has identifiable or affective value: being considered a symbol of a culture or a region, or connected to memories of the past/having an emotional attachment to them (Jia et al. Citation2020).

With this in mind, what has largely been undiscussed in the literature is the effect of silencing sounds of perceived value, or heritage sounds, on the community in the present time. Examples are evident, such as restrictions being placed on generated noise levels alongside music and songs in conjunction with religious processions in Singapore, with participants being evidently frustrated by not being able to immerse oneself in a complete atmosphere containing the typical aural components (Kong Citation2005), but such examples are sparse within the literature. With the knowledge of bellringing being essential in setting quotidian rhythms pre-twentieth century (Corbin Citation1998), and the understanding that the significance on religion has fundamentally shifted in many countries over the last century (Crockett and Voas Citation2006; Voas and Chaves Citation2016), it would be important to know to what extent such value remains in our modern times with increased levels of secularization of daily life. While some indication of this can be gleaned from the enforced silencing of church bells across 2020–2021 due to government-imposed restrictions in a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic (Parker and Spennemann Citation2020; Parker and Spennemann Citation2021), that loss was known to be temporary and a minor aspect in the face of more pressing public health concerns.

Even though many countries have become increasingly secular, sounds emanating from religious spaces, be they bells or the Islamic call to prayer (Azan) remain foci of contention in the current, global socio-political climate. Here covert, deeper social intolerance, if not ethnic or religious hostility, is masked by overt concerns about noise pollution (Efron et al. Citation2020; Parker and Spennemann Citation2022) and political power and sound politics are still being exercised, albeit a veiled fashion in the form of community-based ordinances.

7. Conclusion

As this paper has shown, sounds are an integral part of a community and often of its identity. Consequently, the silencing of public sounds in a community context represents an audible exercise of political control over a populace and a manifestation of political power without the need of an overt show of force. The public spectacle of the removal of bells from their towers can be read as an evisceration of a community where religious sounds are integral to that community. Past events of sound politics, as discussed in this paper, can inform the present, but cannot act as guidance to the impact of future actions of the same ilk, as each sound is unique in its determination both as a soundmark and as an intangible heritage component. Likewise, public reaction to the muting of bells during the COVID-19 pandemic, or the public perception of the frequency and volume reduction of religious sounds has only indicative value as the sound-making devices are still in place. Given the events that played out in the Middle East in the past decade (i.e., the impact of the Islamic Caliphate), and of other conflicts with religious dimensions worldwide, it is predictable that religious sounds will again be silenced in a future conflict.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Akramy, I., and A. K. Hakim. 2021. “Destroyed Bamiyan Buddha Statues Come Back to Life in Afghanistan.” Deutsche Welle, March 12. https://www.dw.com/en/destroyed-bamiyan-buddha-statues-come-back-to-life-in-afghanistan/av-56855226.

- Anonymous. 1940a. En Allemagne. Le Lorrain, March 21.

- Anonymous. 1940b. En Ecoutant Le Son De Cloches. Le Lorrain, 3, March 26.

- Anonymous. 1942. “Ersatz Bells in Italy.” The Ringing World 38 (1,631): 525.

- Anonymous. 1945. Nos Cloches Reviennent. Républicain Lorrain, 2, August 15.

- Assemblée nationale. 1792. Loi relative à la fabrication de la Monnaie provenant du métal des chloches. Donnée à Paris, le 22 Avril 1792. (Décret de l’Assemblée nationale, di 14 Avril 1792) (Lois et Actes du Government (Vol. V Octobre 1791 à Juin 1792 [publ. 1804], pp. 327–329). L’imprimerie Impériale.

- Baier, R. 2013. Spätmittelalterliche/ Frühneuzeitliche Pilgerzeichen in Form von Glockenabgüssen aus Österreich & Glockenabgüsse von österreichischen Wallfahrtsstätten, Universität Wien.

- Basdurak, N. 2020. “The Soundscape of Islamic Populism: Auditory Publics, Silences and the Myth of Democracy.” SoundEffects – An Interdisciplinary Journal of Sound and Sound Experience 9 (1): 132–148. https://doi.org/10.7146/se.v9i1.112804

- Batuman, E. 2009. “The Bells.” New Yorker, April 20. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2009/04/27/the-bells-6.

- BBC News. 2020. “Bell Taken by Nazis to be Returned to Poland.” BBC News, December 29. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-55474030.

- Bendersky, J. W. 2013. A Concise History of Nazi Germany. Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Bevans, C. I. 1969. Treaties and Other International Agreements of the United States of America, 1776–1949 (Vol. 1 Multilateral 1776–1917). Washington, DC: U.S.G.P.O.

- Boucault, M. 1790. A Messieur de l’Assemblée Nationale. Résumé du mémoire présenté à l’Assemblée Nationale, contenant les moyens les plus avantageux de tirer du billon et autres objets. On y a joint quelques pièces de monnaie qu’on propose. Présenté le 25 septembre 1790. Meymac & Cordier.

- Braun, W. 1990. Glockenenteignung 1917/18 im Nürnberger Land (Vol. 39). Altnürnberger Landschaft e.V.

- Burnett, J. 2002. Typikon for Church Ringing. Editorial Board of the Russian Orthodox Church: Moscow

- Byrnes, T. A., and P. J. Katzenstein. 2006. Religion in an Expanding Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Clay, R. 2012. “Smells, Bells and Touch: Iconoclasm in Paris during the French Revolution.” Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies 35 (4): 521–533. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1754-0208.2012.00537.x

- Convention National. 1793. Décret du 23 Juillet 1793, l’an second de la République Française, portant qu’il ne sera laissé qu’une seule Cloche dans chaque Paroisse. Décret n° 1256. (Collection Générale des lois, proclamations, instructions et autres actes du pouvoir exécutif (Vol. 25). L’imprimerie Nationale du Louvre.

- Corbin, A. 1998. Village Bells: Sound and Meaning in the 19th-Century French Countryside. Basingstoke: Columbia University Press.

- Crockett, A., and D. Voas. 2006. “Generations of Decline: Religious Change in 20th-Century Britain.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 45 (4): 567–584. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5906.2006.00328.x

- Daum, A. W., and V. Liebau. 2000. Die Freiheitsglocke in Berlin – The Freedom Bell in Berlin. Berlin: Jaron.

- Dehdari, S. H., and K. Gehring. 2019. The Origins of Common Identity: Evidence from Alsace-Lorraine. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3493660.

- della Dora, V. 2021. “Listening to the Archive: Historical Geographies of Sound.” Geography Compass 15 (11): e12599. https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12599

- Destainville, H. 1920. “La réquisition des cloches dans un district de l’Aube.” Annales Révolutionnaires 12 (3): 209–217. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41921214.

- Dewamin, É. 1895. Cent ans de numismatique française de 1789 à 1889 ou A.B.C. de la numismatique moderne à l’usage des historiens, archéologues, numismates (Vol. 2 Histoire de Numéraire). D. Dumoulin et Cie.

- Diaz, J., C. Hauser, J. M. Bailey, M. Landler, E. McCann, M. Pronczuk, N. Vigdor, and M. Zaveri. 2020. “How Statues Are Falling Around the World.” The New York Times, June 24. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/24/us/confederate-statues-photos.html.

- Duffy, C. 1981. Russia’s Military Way to the West. Origins and Nature of Russian Military Power, 1700–1800. London: Routledge & Keagan Paul.

- Efron, Y., M. LeBaron, M. Senbel, and M. S. Wattad. 2020. “Like a Prayer? Applying Conflicts with Religious Dimensions Theory to the ‘Muezzin Law’ Conflict.” Washington Univeristy Journal of Law & Policy 63:119.

- Engel, M. S., and A. Fiebig. 2022. “Detection and Classification of Soundmarks and Special Features in Urban Areas.” 24th international congress on acoustics, Gyeongju, Korea.

- Falaky, F. 2020. “The Cloche and its Critics: Muting the Church’s Voice in Pre-Revolutionary France.” Journal of the History of Ideas 81 (2): 239–255. https://doi.org/10.1353/jhi.2020.0015

- Finke, W. 1957. “Die Tragödie der deutschen Kirchenglocken.” Schlesische Bergwacht 57 (32): 570–572.

- Freeman, K. 2008. “‘The Bells, Too, are Fighting’: The Fate of European Church Bells in the Second World War.” Canadian Journal of History 43 (3): 417–450. https://doi.org/10.3138/cjh.43.3.417

- Gaucher, C. E. 1790. De la suppression des cloches. Dialogue entre un marguillier de Saint Eustache & un député à l’Assemblée Nationale, sur l’origine & l’usage des cloches, les abus, les accidents qu’elles occasionnent journellement, et les avantages qui résulteroient de leur destruction. Paris: À Philharmonie.

- Georgi. 1917. 227. Verordnung des Ministeriums für Landesverteidigung im Einvernehmen mit den beteiligten Ministerien und im Einverständnisse mit dem Kriegsministerium vom 22. Mai 1917, betreffend die Inanspruchnahme von Glocken für Kriegszwecke. Reichsgesetzblatt für die im Reichsrate vertretenen Königreiche und Länder (Österreich)(92), 586–587.

- Hynson, M. 2021. “A Balinese ‘Call to Prayer’: Sounding Religious Nationalism and Local Identity in the Puja Tri Sandhya.” Religions 12 (8): 668. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12080668

- Ireland, C. 2008. “Rescued Russian Bells Leave Harvard for Home.” Harvard News Office, July 10. https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2008/07/rescued-russian-bells-leave-harvard-for-home/.

- ISO. 2014. Acoustics—Soundscape. Part 1 Definition and Conceptual Framework (Vol. ISO 12913-1:2014(E)). International Standards Organisation.

- Jia, Y., H. Ma, J. Kang, and C. Wang. 2020. “The Preservation Value of Urban Soundscape and its Determinant Factors.” Applied Acoustics 168:107430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apacoust.2020.107430

- Kalkandjieva, D. 2014. The Russian Orthodox Church, 1917–1948: From Decline to Resurrection. London: Routledge.

- Kimmich, C. M. 1969. “The Weimar Republic and the German-Polish Borders.” The Polish Review 14 (4): 37–45.

- Kiser, B. H., and D. Lubman. 2008. “The Soundscape of Church Bells – Sound Community or Culture Clash.” Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 123 (5_Supplement): 3807. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.2935517

- Kong, L. 2005. “Religious Processions: Urban Politics and Poetics.” Temenos-Nordic Journal of Comparative Religion 41 (2): 225–249.

- Kramer, K. 2007. Die Glocke. Eine Kulturgeschichte.

- Lee, H. P., K. M. Lim, and S. Garg. 2019. “A Case Study of Recording Soundwalk of Fushimi Inari Shrine in Kyoto, Japan Using Smartphone.” Noise Mapping 6 (1): 94–102. https://doi.org/10.1515/noise-2019-0008

- Leone, M. 2016. “Hearing and Belonging: On Sounds, Faiths and Laws.” In Transparency, Power, and Control, edited by V. K. Bhatia, 183–198. London: Routledge.

- Levacher. (1917). Ausführungsbestimmungen zu der Bekanntmachung vom 1. März 1917 betreffend Beschlagnahme, Bestandserhebung und Enteignung sowie freiw. Ablieferung von Glocken aus Bronze.

- Louis XVIII, K. 1789. Lettres patentes du roi, par lesquelles Sa Majesté ordonne l’exécution de deux décrets de l’Assemblée nationale, des 7 & 14 novembre, relatifs à la conservation des biens ecclésiastiques, & celle des archives et bibliothèques des monastères & chapitres. Données à Paris le 27 novembre 1789 ((pp. 327–329). B. Gibelin-David et T. Émeric-David.

- Lumans, V. O. 1982. “The Ethnic German Minority of Slovakia and the Third Reich, 1938–45.” Central European History 15 (3): 266–296. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0008938900001485

- Magne, C. 1904. Un Vielle Église de Paris—Saint Médard. Bulletin de la Montagne Ste. Geneviève et ses abords (Ve et XIIIe arrondissements), 4, 9.

- Mahrenholz, C. 1952. Das Schicksal der deutschen Kirchenglocken. Denkschrift über den Glockenverlust im Kriege und die Heimkehr der geretteten Kirchenglocken. Ausschuss für die Rückführung der Glocken.

- McGuire, M. 1997. “Two Resurections.” Chicago Tribune, April 27. https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/ct-xpm-1997-04-27-9704270115-story.html.

- Merland, M. 2012. Il était une fois … le patrimoine campanaire durant la Deuxième Guerre mondiale: la sauvegarde (2e partie). Commission Royale Des Monuments, Site et Fouilles (CRMSF). Accessed July 20. http://www.crmsf.be/fr/actualite/il-%C3%A9tait-une-fois%E2%80%A6-le-patrimoine-campanaire-durant-la-deuxi%C3%A8me-guerre-mondiale-la-0.

- Michalski, S. 2013. Public Monuments: Art in Political Bondage 1870–1997. London: Reaktion Books.

- Mitchell, J. 1840. The Life of Wallenstein, Duke of Friedland. London: J. Fraser.

- Mittié, S. 1789. A l’Assemblée Nationale. Nécessité de diminuer le nombre des gens d’église et fonte des cloches superflues pour en faire de la monnaie et des canons. Paris: Pajot.

- Morelon, C. 2019. “Sounds of Loss: Church Bells, Place, and Time in the Habsburg Empire during the First World War.” Past & Present 244 (1): 195–234. https://doi.org/10.1093/pastj/gtz006

- Nash, G. B. 2010. The Liberty Bell. New Haven: Yale University Press. https://doi.org/10.1298/79780300163148

- Parker, M., and D. H. R. Spennemann. 2020. “Anthropause on Audio: The Effects of COVID-19 Pandemic on Church Bell Ringing in New South Wales (Australia).” Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 148 (5): 3102–3106. https://doi.org/10.1121/10.0002451

- Parker, M., and D. H. R. Spennemann. 2021. “Responses to Government-Imposed Restrictions: The Sound of Australia's Church Bells one Year after the Onset of COVID-19.” The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 150 (4): 2677–2681. https://doi.org/10.1121/10.0006451

- Parker, M., and D. H. R. Spennemann. 2022. “Conceptualising Sound Making and Sound Loss in the Urban Heritage Environment.” International Journal of Urban Sustainable Development 14 (1): 264–286. https://doi.org/10.1080/19463138.2022.2103821

- Price, F. P. 1948a. “The Bells Came Down.” Michigan Alumnus Quarterly Review 52 (10): 9–18.

- Price, F. P. 1948b. Campanology, Europe, 1945–47: A Report on the Condition of Carillons on the Continent of Europe as a Result of the Recent war; on the Sequestration and Melting Down of Bells by the Central Powers; and on Research Into the Tonal Qualities of Bells Made Accessible by War-Time Dislodgment. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Richard, B. 2012. Les cloches de France sous la seconde guerre mondiale. Société Française de Campanologie(Patrimoine campanaire 69).

- Rombouts, L. 2014. Singing Bronze: A History of Carillon Music. Leuven: Leuven University Press.

- Saam, A. n.d. Die Kirchenglocken im Markt Burkardroth. Kurze Geschichte der Glocken im Allgemeinen. (Vol. 39). Stadt Markt Burkardroth. https://www.burkardroth.de/pfarreiengemeinschaft/kirchenglocken/m_2941.

- Sartori, P. 1932. Das Buch von deutschen Glocken. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

- Schilling, F. 1954. Unsere Glocken. Thüringer Glockenbuch. Gabe der Thüringer Kirche an das Thüringer Volk. Jena: Wartburg Verlag.

- Schmidt, A. 1986. “Geschichte und Symbolik der Glocken.” In Glocken in Geschichte und Gegenwart, edited by K. Kramer, 11–19. Karlsruhe: Badenia Verlag.

- Schubert-Soldern, F. v. 1919. “Metallbeschlagnahmung in Österreich.” In Kunstschutz im Kriege. Berichte über den Zustand der Kunstdenkmäler auf verschiedenen Kriegsschauplätzen, edited by P. Clemen, 215–221. Leipzig: E. A. Seemann.

- Schwarz, O. 2014. “Arab Sounds in a Contested Space: Life Quality, Cultural Hierarchies and National Silencing.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 37 (11): 2034–2054. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2013.786109

- Shapreau, C. 2019. “Bells in the Cultural Soundscape: Nazi-Era Plunder, Repatriation, and Campanology.” In The Oxford Handbook of Musical Repatriation, edited by F. L. Gunderson, C. Robert, and Bret Woods, 503–530. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Spennemann, D. H. R., and M. Parker. 2022a. “Sounds of Patriotism and Propaganda: The Case of the Church Bell of Marquillies (Département du Nord, France).” Journal of Conflict Archaeology 17 (3): 184–203. https://doi.org/10.1080/15740773.2022.2136988

- Spennemann, D. H. R., and M. Parker. 2022b. “To Ring or Not to Ring: What COVID-19 Taught Us about Religious Heritage Soundscapes in the Community.” Heritage 5 (3): 1676–1686. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage5030087

- Stockmann, D. 1974. “Der Kampf um die Glocken im deutschen Bauernkrieg. Ein Beitrag zum öffentlich-rechtlichen Signalwesen im Spätmittelalter.” Beiträge zur Musikwissenschaft 16:163–193.

- Timasheff, N. 1941. “The Church in the Soviet Union 1917-1941.” Russian Review 1 (1): 20–30. https://doi.org/10.2307/125428

- Vladykin, A. 2002. “Russian Bells Are Ringing In New Era of Religious Freedom.” LA Times, January 20. https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2002-jan-20-mn-23805-story.html.

- Voas, D., and M. Chaves. 2016. “Is the United States a Counterexample to the Secularization Thesis?” American Journal of Sociology 121 (5): 1517–1556. https://doi.org/10.1086/684202

- Vogel, R. 2009. Die militärische Requisition der Glocken in den Dekanaten Freudenthal / Bruntál o. Bruntál, Jägerndorf / Krnov o. Bruntál und Troppau / Opava o. Opava im Jahr 1917 in Österreich – Schlesien und Schlesien. Heimatkreis Freudenthal.

- Weinberg, G. L. 1994. A World at Arms: A Global History of World War II. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Williams, E. V. 2014. The Bells of Russia: History and Technology. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Wood, A. 2013. “Urban Soundscapes: Hearing and Seeing Jerusalem.” In The Routledge Companion to Music and Visual Culture, edited by Tim Shepard and Ann Leonard, 286–293.

- Wood, A. 2015. “The Cantor and the Muezzin’s Duet: Contested Soundscapes at Jerusalem’s Western Wall.” Contemporary Jewry 35 (1): 55–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12397-015-9136-3

- Yelmi, P. 2016. “Protecting Contemporary Cultural Soundscapes as Intangible Cultural Heritage: Sounds of Istanbul.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 22 (4): 302–311. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2016.1138237

- Yilmazer, S., and V. Acun. 2018. “A Grounded Theory Approach to Assess Indoor Soundscape in Historic Religious Spaces of Anatolian Culture: A Case Study on Hacı Bayram Mosque.” Building Acoustics 25 (2): 137–150. https://doi.org/10.1177/1351010X18763915

- Zhang, D., M. Zhang, D. Liu, and J. Kang. 2018. “Sounds and Sound Preferences in Han Buddhist Temples.” Building and Environment 142:58–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2018.06.012