ABSTRACT

Despite the shift from object- to landscape-based approaches in urban heritage management, the analysis of heritage as objects is still viable, as the current archaeological theories of material culture do not see objects in the same manner as the object-based approach. To reveal the broader significance of urban archaeology for the cityscape, the relationship between the discipline and urban space is analyzed in the framework of fragmentation theory. The theory is based on prehistoric archaeology but modified to describe urban archaeology and its effects in the contemporary city. It is argued that fragments, regardless of their connection with the past and their central role in heritage work, also have autonomous potential to distract and act as agents disconnected from their original objects. The creative character of urban fragments should be explored further by archaeologists and heritage management. These ideas are scrutinized using the development of urban archaeology and heritage in the city of Turku in Finland as an example.

Introduction

In 2011, the UNESCO General Conference adopted the “Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape,” which guides national and local governments to embed a landscape-based approach into heritage management. In the document’s glossary, the definition of “historic area/city” mentions archaeological sites as part of the urban environment, and among the ways of identifying the value of such areas, the archaeological point of view is recognized as well. Hence UNESCO’s recommendation reinforces the development in which urban archaeology becomes incorporated into a wider spectrum of urban safeguarding, conservation and management practices (Jokilehto Citation1998). Such a holistic attitude is based on the conviction that archaeology consists not only of fieldwork, but crucially also engagement with the public and co-operation with urban planning (e.g., Lamb, Citation2008; Guttormsen Citation2020).

Alongside the “Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape,” scholarship on urban heritage has outlined a shift from an “object-based” to a “landscape-based approach” (e.g., Veldpaus, Roders, and Colenbrander Citation2013, 3; Williams Citation2014). The former focuses solely on tangible heritage and the conservation of individual monuments. The latter, in contrast, is a more comprehensive stance, encompassing also intangible values and traditions and acknowledging larger social and economic processes in the urban society. Although such a dualistic view may be useful in describing differences in managerial practices, it is a disadvantageous starting point for theoretical discussion, as it does not recognize the elaborate conceptual work on the cultural complexity and historicity of material objects that archaeologists have conducted. In addition, the reductive attitude of the dualism can belittle the importance of materiality in understanding the cityscape. In this theoretically oriented article, I aim to show that object-based analysis of urban heritage is still viable if the notion of object is revised. To do this, I will take up fragmentation theory from prehistoric archaeology and modify it to describe urban archaeology and its effects in the contemporary city. The central question in this article is how fragmentation theory can be used in the study of urban heritage.

Central to my venture is the concept of fragment, which refers to the remnants or traces of past life – structures and artefacts – lying underground or belonging to the urban landscape. A fragment is “a part broken off or otherwise detached from a whole” (OED Citation2023), like archaeological finds – i.e., pieces of entities which were intact in the past. Archaeology and heritage studies can thus be described as disciplines of fragments. According to Michael Shanks (Citation2012, 25), the core of the archaeological imagination is the creative impulse to reanimate the fragments of the past. Rodney Harrison (Citation2020, 45) argues correspondingly that heritage work is always concerned with the maintenance of fragments (cf. Guttormsen and Skrede Citation2022, 30).

Fragments are present in urban archaeology in many forms (e.g., Sörman, Noterman & Fjellström, Citation2023). In excavations, the ground is opened and dissected into units which are equivalent to structures, objects, and soil layers. Based on this removal and reconstruction work, archaeologists present interpretations of the ancient remains as a whole. Fieldwork is thus characterized by the tension between fragmenting the ground and putting things back together. Moreover, it involves not only drawing conclusions from the fragments of artefacts and building remains that are revealed but also has an impact on the urban environment. Together with other heritage professionals and urban planners, archaeologists decide what is removed and destroyed, what is taken into museum collections, and what is saved in the urban environment in situ. Besides these tangible manifestations of fragmentation, fragmentation theory also brings out the intangible significance of ancient remains in urban setting and integrates it into the notion of archaeological heritage.

Fragments are a crucial part of urban archaeology, and they are frequently mentioned in literature on urban heritage and its management (e.g., Colavitti Citation2018, 11). Urban fragments are usually discussed as something to be preserved (Karimi Citation2000) and curated (Warnaby Citation2019), but Elke Ennen (Citation1997) characterizes urban fragments as a part and symptom of post-modern society. Nadia Bartolini (Citation2014), in turn, focuses on a concept close to fragment and fragmentation, i.e., palimpsest, and how it metaphorically describes the chronological superimposition of urban remains. In addition, ruins as a cultural phenomenon characteristic of the modern period have attracted considerable scholarly attention, and some of the literature also has implications for urban heritage in general (Kirchmair Citation2023; Schnapp Citation2018; Citation2020).

The concept of fragment and related terms are frequently used in literature on urban heritage, but there is no uniform approach to them. One reason might be the lack of an easily applicable theory on fragments and fragmentation. The ruination of modern architecture and the decay of contemporary material culture has received theoretical interest in contemporary archaeology in recent decades (DeSilvey Citation2017; McAtackney and Ryzewski Citation2017; Pétursdóttir and Olsen Citation2014). In prehistoric archaeology, in contrast, the so-called fragmentation theory has been developed to engage with premodern forms of breakage and analyze wider temporal scales than modernity. Since urban heritage consists of both modern and premodern fragments, I borrow and transform the theoretical ideas represented in prehistoric archaeology to approach urban heritage. To show how fragmentation theory deepens the understanding of archaeology and archaeological heritage in cities, I will begin by presenting Chapman’s thoughts on fragments and examine how his theory can be applied in the analysis of an urban context. I will use the city of Turku and its archaeological remains as an example.

Turku is a coastal city of 200,000 inhabitants, located in South-Western Finland, about 170 km to the west of Helsinki. Founded in around 1300 (Immonen, Kinnunen, and Harjula Citation2022; Savolainen, Hannula, and Välimäki Citation2021), it is the oldest city in the country and remained Finland’s most important city throughout the period of Swedish rule (c.1150–1809) after which the capital was moved to Helsinki. Archaeological activities and remains have become an established part of the Turku cityscape, the latest example of which is the extensive archaeological excavation that took place in near the old city center in summer and autumn 2023 (Lammassaari Citation2023). The analysis of archaeological fragments in Turku is based on previous archaeological literature, news items in the local media, documents related to decision making processes in the city, and observations at archaeological sites in the city center. I will discuss the development of urban archaeology in Turku and how archaeological practice along with its fragments became a component in the urban lifestyle and both tangible and intangible heritage. Finally, I will look to the ways in which the dynamics of fragmentation affects the presence of archaeological heritage in Turku, and evaluate the use of fragmentation theory in the study of urban heritage.

Core Concepts: Fragmentation, Enchainment, and Accumulation

Urban archaeological heritage, consisting of the remains of buildings and artefacts, as well as the evolution of the urban plan, can be studied using the theory of fragmentation. Chapman laid the foundations for the theory in Fragmentation in Archaeology: People, Places and Broken Objects in the Prehistory of South Eastern Europe (Citation2000) and developed his ideas in subsequent publications (e.g., Chapman Citation2013; Chapman and Gaydarska Citation2006). Other scholars have continued to apply, criticize, and cultivate fragmentation theory, mainly to study prehistoric cultures (e.g., Brittain and Harris Citation2010; Gamble Citation2007; Mantere and Kashina Citation2020; Morton, Awe, and Pendergast Citation2019). The theory has garnered less popularity in historical and contemporary archaeology, although it offers a specifically archaeological approach to fragments and their significance.

For Chapman (Citation2000), the fragmentation of artefacts is not explainable only by accidents and natural processes affecting the archaeological record. In some cases, the pieces of ancient objects can indicate intentional actions which aim at constructing the material and social reality through breaking things. The concept of fragmentation describes such deliberate production of fragments (Chapman Citation2000), the distribution of those pieces to different locations and symbolic contexts, and the subsequent possibility of gathering the fragments together again. Despite the transportation and dispersal of fragments, they retain the material as well as socio-cultural connection to their original, no longer existing whole. This allows them to be used in the materialization and maintenance of social ties in the community which created the original object and shattered it.

According to Chapman (Citation2000), fragmentation is related but antithetical to the concept of accumulation. The latter denotes amassing together objects or their pieces to accrue the social or economic capital invested in them. The value of such collections is not, first and foremost, in the social cohesion and ties they institute, but in their totality, or how extensive and complete they are. Instead of individual fragments, what matters is the total number of items and their contribution to the value of the whole. For example, in a silver hoard, coins function solely as units of material value, not as individualized objects with histories and meaning like in fragmentation. Similarly, creating private collections of antiquities or other showpieces and even museum collections may be accumulative in nature.

Along with fragmentation and accumulation, the third key concept of Chapman’s theory is enchainment. It denotes the use of object pieces to reinforce social and material relationships in a more historically sensitive way than in accumulation. In enchainment, fragments become tangible parts of the chains of production, consumption, and use, and this materially defined network becomes intertwined with the social and cultural effects of objects and their fragments. The agency of objects is based on their physical characteristics but also their histories, which can also be called their biographies or itineraries. An itinerary consists of the origins of the object’s materials, and the practices and skills of its makers, as well as the account of its owners and users, and even the variety of its uses and the locations of these uses (e.g., Appadurai Citation1986; Joy Citation2009; Joyce and Gillespie Citation2015; Sørensen and Viejo-Rose Citation2015). When an object is broken into fragments, they multiply and continue the itinerary of the original. Although physically independent, the fragments extend the reach of the initial object in different contexts. A modern fragment can be the stub from a ticket of an exceptionally well-received film, kept as a memento, or it can be a piece of jewelery whose parts are shared by lovers to remind of their mutual affection. Fragments evoke memories and emotions, and connect places and people in concrete, metonymic as well as metaphorical ways.

Chapman (Citation2000) argues that in enchainment, fragments retain their historical connection to the initial object and the people who used it, but, at the same time, they hold the potential to define the connections in a novel fashion. In this manner, the fragments organize the environment into wholes and parts and make reality intelligible. This view can be expanded with Bartolini’s (Citation2014) argument that fragments might not originate from an actual common whole, and their itineraries may be entirely imagined. In other words, fragmentation, as much as it is a material phenomenon, also affects and transforms this materiality by creating new narratives and meanings, showing the how tangible and intangible heritage are interwoven. Hence, in some situations, it is more relevant to chart the effects of fragments than to focus on estimating the historical accuracy of fragmentation.

Beyond the conceptual framework, fragmentation theory does not offer an overarching methodology (Gaydarska Citation2023, 104). Archaeologists have utilized a variety of individual methods in analyzing pieces of artefacts and other remains, examining their material qualities and reconstructing the relationships between fragments and wholes. Such technically oriented methods are not often useful in approaching urban heritage, and even methods with a more cultural or social emphasis can be problematic, as fragmentation is contextually specific and thus requires methodological sensitivity. Instead Bisserk Gaydarska (Citation2023) suggests that fragmentation theory aims to capture the performative or creative aspects of fragmentation and the agency of fragments as well as communicating them in scholarly or other narratives.

Fragmentation in the Urban Environment

As the concepts of fragmentation, accumulation, and enchainment are transported to the analysis of archaeological urban heritage, a set of problems arises. The first issue is to what extent urban remains uncovered by archaeologists can be considered consequences of fragmentation. They are not created by design, but are the result of multiple, disparate and parallel processes of demolition, build-up, and relocation. Moreover, although urban archaeologists can anticipate the remains that may be uncovered based on archival sources, remote sensing and educated guesses, the places to be investigated are not usually decided by heritage professionals but determined by redevelopment. The fragmentation of urban archaeological heritage is therefore not, in a narrow sense, intentional, but a mixture of intentional acts and unintentional events. However, as Bartolini (Citation2014) suggests, fragmentation can function even without original objects or wholes, and this is crucial when the urban environment and archaeological remains are approached from the perspective of fragmentation theory.

The second problem of transferring fragmentation theory into urban archaeology is the precarious relationship between the whole and its fragments. In many earlier archaeological applications of fragmentation theory, this relationship was seen rather rigidly, as something that was self-evident and known, since the same people who made the portable objects also broke them and distributed the pieces. Consequently, the fragment necessarily remains conditioned or defined by the initial object. This is also apparent in the so-called cultural biographical approach to objects, which frequently is based an assumption of uniform objects and their orderly histories (Jones, Diaz-Guardamino, and Crellin Citation2016). The notion of fragment challenges such an idea of charting the life course of a materially circumscribed object. When a fragment, the material item involves at least two biographies simultaneously: one of the original and the other of its own. Furthermore, it is difficult to define from which wholes urban archaeological fragments actually derive. Are they fragments from a built structure, like the foundation of a house, or should they be seen more broadly as fragments of the ancient city or even the entirety of past life? Such questions stem from the absence of an intentional and portable object assumed by many applications of fragmentation theory. This limitation can be overcome by arguing that the category of objects is more complex and flexible than portable objects might suggest, giving any fragment also the status of an object. In fact, the same fragment can derive from many objects – objects like a built structure, city, or the past life – and participate in their biographies simultaneously.

Romanticism established an intellectual tradition which emphasizes the autonomous character of fragments. For instance, Friedrich Schlegel (Citation1798/1967, 169, 197) compares the fragment to a work of art, arguing that it is detached from the rest of the world and self-contained (Bradshaw Citation2007). Schlegel’s argument can also be made about urban archaeological fragments. The stone foundation of a demolished building, when unearthed in an excavation pit, is no longer part of the original object, whatever that is, but it is still not yet in the service of contemporary life, although it can soon be made into a source of learning, entertainment, and wellbeing. In this in-between state, it is synchronously a fragment of a larger whole and a self-contained item (Brittain and Harris Citation2010, 589). Urban archaeological remains are physically independent entities, and in fact, the whole of the city’s past is reconstructed and made knowable through them, revealing that the assumed initial object is conditioned by its parts. Based on Shanks (Citation2012) and Harrison (Citation2020), it can be argued that defining these part–whole and past–present relationships are at the heart of urban archaeology.

After these revisions, I suggest that fragmentation describes, firstly, the acts of the archaeologists who make the ancient remains visible and interpret the original whole from which they derive. As a discipline, archaeology integrates fragments of the past into its knowledge production, generating information on the location, its history, and the value of heritage. Ultimately archaeologists link these fragments to the identity of the city and its inhabitants. Secondly, fragmentation defines the relationship between the ancient remains and the contemporary people living in the city. Some might consider archaeological fragments irrelevant, but they nevertheless remain distinct from other elements in the cityscape. This alienness is often conceptualized in terms of temporal distance (cf. Sjöstrand Citation2010, 254): because urban fragments are old, they seem strange.

For many who encounter ancient remains, they become interpreted as fragments of past life transmitted to modernity. Although urban fragments prompt various readings and feelings, in many cases, they are made legible by heritage professionals (Williams Citation2014). Wherever the interpretations stem from, the fragments do not belong entirely to either the past – since they are physically present with us – or the present – as they are vestiges of bygone acts and events (Olivier Citation2011). Fragmentation is a process which molds these archaeological remnants into something intelligible, designating the past city as the whole from which the fragments emanate. This connects the remains with the contemporary landscape, and thus fragmentation identifies some objects as fragments and invests them with significance and the ability to affect us.

While fragmentation forms a broad context for approaching urban heritage, the concepts of enchainment and accumulation help to describe different relationships with fragments. Enchainment forges an active relationship between items of urban heritage and their origins, whether actual or imagined. It expands and reinforces the agency of the original, its makers and other factors which have affected the fragments. These effects assume a variety of expressions, ranging from being part of the underground layers of soil to influencing not only the movements of contemporary inhabitants and visitors but also urban planning and notions of the past.

Since such agency stems from the materiality of fragments, it is not necessarily tied to fragments becoming identified or treated has heritage, but heritagisation of such fragments nevertheless transforms the field and scope of their agency. This is based on enchainment’s potential to bring together tangible and intangible, actual and imagined elements. Conversely, heritagisation can alter the origins and agency of fragments because it can enchain fragments in novel ways. For instance, after the modern profession of archaeologists emerged, these experts became invested with authority to direct the enchainment of urban fragments through their interpretative work. Analyzing enchainment and its changes is thus pivotal for studying urban heritage.

Accumulation can be seen as an opposite of enchainment as it does not generate social or economic effects based on the relations between the whole and its fragments. In contrast, only the number and distribution of fragments is of significance. However, the heritagisation of urban fragments complicates the process of accumulation, because already the act of identifying the fragments as pieces of the past city connects enchainment with accumulation. Accumulating urban fragments can be technical when they are uncovered by modern land use, requiring perhaps further resources to demolish or document and preserve the ruins. Accumulation can also refer, for instance, to the distribution and concentrations of fragments in the urban landscape. Where are the protected fragments located? Nevertheless, through heritagisation, the same fragments gain value as traces of the past and become enchained to the ancient city. Hence, enchainment allows urban fragments being utilized as a calculable resource for tourism, wellbeing, and social cohesion. The tension between enchainment and accumulation is especially apparent in urban heritage management, where the logic of resource allocation is based on the need to preserve the enchained fragments and their agency. Consequently, the analysis of urban heritage as fragments requires tracing the patterns of accumulation and the frictions between accumulation and enchainment.

Ultimately approaching urban heritage through fragmentation theory brings out the tangible and intangible effects of physical fragments. It emphasizes that their enchainment is a process of discovery, negotiation, and transformation. Moreover, like heritagisation, also enchainment is a historical process, which can be traced back in time and which actively defines our relationship with urban fragments. In addition, fragmentation theory reminds that the management of urban fragments involves issues of contemporary land use and conservation of ancient remains, but the presence and agency of fragments it tends are historically conditioned and intertwined with intangible heritage. Yet, alongside with social and value creation processes, fragmentation theory also preserves the object-like and potentially autonomous character of fragments. The theory conceptualizes fragments as creative entities in the core of heritage analysis, not to be side-lined, for instance, by social, scholarly and economic factors. Equipped with this conceptual framework of fragmentation, enchainment and accumulation, I will move on to urban archaeology in Turku, and its effects on the city’s landscape.

The Beginnings of Urban Archaeology in Turku in the Early Twentieth Century

Approaching urban archaeological heritage from the point of view of fragmentation stresses the itineraries of ancient remains and their emergence in the cityscape. Yet these fragments have been present in urban areas long before archaeology existed as a modern discipline. In Turku, artefacts and the debris of old buildings were known to lie underground already centuries ago. In 1700, Prof. Daniel Juslenius (Citation1700/2005) describes ancient structures uncovered in the town, recounting an oral tradition that medieval monks built underground passages in Turku. However, for Juslenius, such fragments did not constitute a source of information requiring documentation and preservation. This is a case in point on the power of enchainment instituted by later heritagisation.

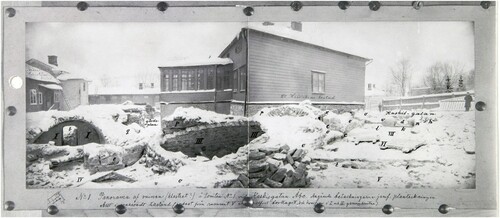

When archaeologists began their work in Turku in the early twentieth century (Taavitsainen Citation2003), they first had to justify the rationale of their fieldwork and legitimate their interpretations of urban fragments as superior compared with previous ones, such as those suggested by oral traditions. Around 1900, many construction projects for novel multi-storeyed buildings were launched in the center of Turku. One of these took place on the plot at Kaskenkatu 1. For decades, human remains had been found in the area and associated with the medieval Dominican convent of St Olaf (Immonen Citation2019). In 1900, a building permit for a new stone house was granted to the plot’s owner. Digging for the foundations began in 1901, and soon old vault structures were revealed .

Figure 1. Panoramic view of the building remains uncovered on the plot of Kaskenkatu 1 in 1901. Photo: Turku Museum Centre.

The archaeologist and conservator Hjalmar Appelgren from the Archaeological Bureau in Helsinki, later renamed the State Archaeological Commission, arrived in Turku and followed the digging for a couple of weeks. He argued that the ruins had indeed belonged to the Dominican convent. This new discovery was reported in local newspapers, which praised the plot’s owner for informing the authorities about the ruins, leading to an important fragment of the city’s past to be found.

Appelgren (Citation1902) published the results of his fieldwork in a manifesto titled “Turku Underground.” The title resonates with Juslenius’s account on the tunnels running underneath the city, and the text attracted a great deal of attention. The terminology is still used in news coverage of archaeological fieldwork in Turku (MTV Uutiset Citation2019), and in the name of an archaeological pop-up museum – “Turku Goes Underground” – in 2019. However, Appelgren’s slogan is more than just a reference to the fragments of subterranean structures. It was a statement which linked the fragments into a meaningful whole and established an idea of documenting the remains and saving the artefacts uncovered in the urban area. Without that, the fragments would remain mute.

For a long time, archaeological research in Turku assumed that none of the building fragments uncovered could or should be preserved. Heritagisation and associated enchainment of urban fragments did not give them value to be preserved at site. A telling exception was the archaeological monitoring of the 1952 and 1953 sewer line excavation which ran through the oldest part of the city along the Aurajoki River (Valonen Citation1958). This and other twentieth-century excavations were conducted by the Historical Museum of Turku, renamed as the Turku Museum Centre in 2009. On the route of the sewer line, many building remains were uncovered and documented. One of the exposed log structures was lifted from the ground and moved to a museum exhibition in Turku Castle. There the wooden fragment along with smaller artefacts were enchained to scholarly work, the history of the city, and local identity.

From Research to Conservation and Display in the Latter Part of the Twentieth Century

The program of Turku Underground conjured up an image of a treasure chest of the past waiting in the urban soil, which archaeology was called upon to salvage. The agenda had success in the early decades of the twentieth century, as several sites were archaeologically documented, and the results were incorporated into the historiography of the city. However, in Finland, the medieval period lost much of its appeal after the Second World War. Reasons for this development were manifold, but the main factor was Finland’s defeat to the Soviet Union and the subsequent need to downplay the nationalist, even militant tone of history writing in the pre-war years in which the Middle Ages had played a pivotal role (Fewster Citation2006, Citation2011). The containment of the problematic period led to the decline of urban archaeology in Turku.

In Europe, urban archaeological methods and heritage management evolved dramatically in the 1970s and 1980s (Belford Citation2020, 41–42; Willems Citation1998). In Turku, too, there emerged a renewed interest in archaeological remains. In contrast to the earlier part of the century, the archaeological debate emphasized the high quality of modern fieldwork (e.g., Kostet and Pihlman Citation1989), and it was declared that the investigations done earlier were unreliable. Only now could proper scholarly or “scientific” excavations be carried out in Turku. This reference to scientific standards became the framework for urban archaeology and justification for the way in which the fragments were to be handled. Methodological rigor also meant a significant increase in the expense of fieldwork, which under the 1963 Antiquities Act were to be covered by the party responsible of the construction work.

In Turku, the valuation and protection of urban heritage developed drastically after public criticism. In the 1960s and 1970s, the city became infamous for the maltreatment of its historical buildings. In fact, the term “Turku Syndrome” was coined to describe the unscrupulous demolition of old buildings to make way for the construction of modernist apartment blocks, and the related corruption at the highest levels of the city’s public and private sector (Klami Citation1982). The first popular movements to preserve historic districts appeared, and public demonstrations took place when old buildings were demolished (Jauhiainen Citation1997). Gradually these movements led to a better and more systematic preservation of old architecture and urban landscapes in the city and altered the planning of land use. Although archaeological remains were not explicitly part of these debates, attitudes towards them also began to change.

In the 1970s, the first archaeological fragments were made permanently visible in the cityscape. Investigations carried out on a street next to Turku Cathedral revealed remains of medieval buildings, including the presumed residence of the Bishop of Turku (Brusila and Lepokorpi Citation1981; Ratilainen Citation2018). The foundations of these buildings were covered up but marked on the street with paving stones that differed from the rest of the paving. The underground fragments thus seem to echo on the street’s surface. Further progress in the visibility of the archaeological heritage was made in the following decades, when some of the structures found in the ground were not demolished during construction activities but came to be maintained as ruins. The first of these sites was the early-modern Church of the Holy Spirit, which was excavated in the 1980s and converted into a private chapel opened in 1992 (Kalpa Citation2011). A more extensive heritage project took place in the mid-1990s, when in-situ cellars and foundations of medieval stone houses were incorporated into the new Aboa Vetus Ars Nova Museum as a major attraction (Lehto-Vahtera and Holkeri Citation2012). The museum is one of the most visited in Turku .

In 2003–2005, large excavations were conducted in the area where a new wing was constructed for the Turku City Library (Saloranta Citation2019, 108–109). Some of the archaeological fragments were left in place, and they can be seen through a glass panel in the ground in the library’s courtyard. In addition, in 2005, a monument to the Dominican convent was unveiled in Olavinpuisto Park, indicating the underground architectural fragments of the medieval institution (Turun Sanomat Citation2005). This sort of visibility of archaeological heritage in Turku is still relatively recent, but archaeological excavations have nevertheless come to be conducted regularly, attracting a lot of public attention and visitors. In other words, archaeology has made a gradually more successful claim on the processes of urban fragmentation and enchainment, and this has had consequences for the development of the cityscape.

The Globalisation of Urbanism in the Twenty-first Century

Although the Antiquities Act governing the protection of archaeological heritage in Finland has remained largely untouched since 1963, the administrative structures and principles of heritage management have significantly changed in the twenty-first century. Archaeological heritage has been integrated into urban and rural planning of land use. While in the previous century the management of archaeological remains meant their protection and study as individual monuments, in the new millennium, archaeological heritage is approached in the larger context of urban landscape and its development. Another recently instituted aim is to involve citizens in the protection of archaeological fragments. These trends can also be seen in Turku.

Firstly, enchainments linking archaeological fragments to the past allow communities and individuals to organize around them and attach their local identities to urban heritage. Fragments connect us with the past and shape the present (Schaepe et al. Citation2017). In heritage management, tapping into this potential has required experts to enchain urban fragments more decisively and explicitly with wider contexts of meaning (e.g., Smith Citation2006). Although archaeologists have never been the gatekeepers for the meanings the urban fragments have prompted in the wider public, their professional role has changed from that of authoritative educators to actors in a democratic society (Matsuda and Okamura Citation2011). There are also more dissident voices as well as outright indifference, although for many members of the urban community, heritage professionals still enjoy a great deal of appreciation. Urban archaeological heritage is becoming part of a more dispersed and diverse range of urban communities and uses, and professionals address this variety of audiences by showing how archaeological fragments can be theirs as well. Consequently, public engagement in heritage management is adopting more participatory modes, such as inviting volunteers to take part in fieldwork in the Aboa Vetus Ars Nova Museum (Aalto Citation2020), or help in the management of archaeological collections of the Turku Museum Centre (Hänninen Citation2022). Archaeology has started to become vocal in framing local identities and providing resources for civic and community engagement (Williams Citation2014).

Secondly, an aspiration to integrate archaeology into heritage management has strengthened along with the need to commodify cultural heritage and utilize it as a resource for tourism and wellbeing (Monckton Citation2022). In addition, in the mid-2010s, the Turku Museum Centre, which so far had been responsible of all urban excavations, acquired a purely administrative role, and fieldwork operations were given to archaeological firms based on competitive procurement. Urban archaeologists in heritage institutions are uneasy with this development since they do not want to see archaeological fragments as economic products (van Londen Citation2016). Their sentiment can be explained as a reaction to the shift of emphasis from fragmentation to accumulation, where the itineraries and connectivity of fragments become irrelevant at the expense of identifying and calculating heritage units and governing them. Losing enchainment dilutes the agency of fragments, and this also impacts the professional role of archaeologists.

In response to the cultural and economic currents of the twenty-first century, the notion of the “deep city” was recently introduced to counterbalance such popular terms as “green city” or “smart city” (Fouseki, Guttormsen, and Swensen Citation2020), the former referring to ecologically and the latter to technologically oriented urban planning. While these oft-repeated visions of contemporary cities highlight the present and the future of urban living, the deep city, in contrast, is a reminder that cities are entities shaped by long local and global histories. This has led some scholars to emphasize that it is important to be aware of the urban temporal depth and incorporate its experts, i.e., archaeologists, into urban planning (e.g., Seppänen Citation2020). With the concept of the deep city, archaeological fragments are traced back to a new object, the historical genuineness of urbanism, which, in turn, is argued to revitalize and guide urban life into new and better paths.

The need for deep cities stems from globalization with its immense economic and managerial effects. In Turku, this is reflected in a vision statement on the development of the city center commissioned by the City of Turku (Keskustavisio Citation2017). The document published in 2017 introduces the internationally well-established concept of the old town in Turku where it had not been used before. The document defined the Old Town as stretching from Turku Cathedral to the Olavinpuisto Park (Immonen et al. Citation2021), comprising the medieval urban area. The Old Town concept highlights the cosmopolitan character of the city and puts Turku on a par with famous foreign cities with historic centers. Importantly, the Old Town has applications in advertising and tourism, too. The term was quickly adopted into public local discourse in Turku, and one of its recent expressions are the wayfinding signs, or signposts with maps, erected in the city center since 2020. They are almost identical in shape and graphic design to wayfinders in New York and London, marking the Old Town of Turku as a welcoming space for domestic and foreign tourists .

Results and Discussion

When the presence of archaeology in the cityscape of Turku is seen in the light of fragmentation theory, the first observation to emerge relates to the character of urban excavations and the fragments they reveal. Juslenius’s account, written before the modern discipline of archaeology, shows that people knew of such remains, but there was no notion of them holding relevant information about the past. The fragments were recognized but not enchained as heritage of the past life. Against this attitude, archaeological fieldwork appeared as interrupting the seemingly coherent urban environment, tending to the fragments hidden underground that otherwise were rarely visible and which most considered inconsequential debris.

Another observation is that, in addition to excavations, the parameters of urban routines are challenged or disrupted by archaeological heritage (Wang Citation2023), especially in Turku with its modern layout and building stock. When left in place, the fragments puncture the temporal and often also architectural or physical coherence of the cityscape, and they can be experienced as a diversion, both in the positive and negative senses of the word. On the other hand, despite their disruptive quality, the fragments are quite fragile, usually removed after discovery, and preserved only in special circumstances, even then requiring constant maintenance. The disruptiveness and fragility are related to accumulation of urban fragments and how much is tolerated to compensate their value as heritage.

Belford and Bouwmeester (Citation2020, 210) compare urban archaeology, or rather the fragments it uncovers, to the photo album belonging to a person suffering from dementia: the events depicted in its pictures have been forgotten, but the physical photographs remain. Similarly, the specificity of archaeological fragments, ruins prompting alienation, contrasts with still-standing protected buildings, which in Finland are mostly well-kept and integrated in the urban fabric. The disruptiveness of archaeological fragments is part of their autonomy. They hold an element of surprise, and the possibility of being taken into various uses, not just those endorsed by heritage management, although their presence in the cityscape is based on work done by heritage experts and urban planning.

Archaeology seeks to enchain ancient remains to the actual or imagined wholes, and this work has been pivotal for their presence in Turku. The production of scholarly knowledge to do this was the main justification when urban archaeology was launched in Turku. At the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, urban development underwent a major change, with wooden houses being replaced by apartment blocks of concrete and stone. They required foundations which penetrated much deeper into the ground, and Appelgren expressed concern that without proper documentation the archaeological evidence of the past, its fragments, would be entirely lost. Archaeology gave new life and significance to the disappearing detritus.

According to Appelgren, in Turku, beneath everybody’s feet, lay a great historical and cultural treasure trove. The city that once was could still be seen in its forgotten fragments, but this required archaeological effort. In the 1960s and 1970s, stemming from grass-root activism, a more systematic interest in Turku’s urban heritage developed, first in relation to city districts and historic architecture, but this led also to a renewed interest in the city’s archaeological heritage. Urban archaeologists begun to point out the accumulative value of those fragments by emphasizing the high quality of their modernized fieldwork practices. Precision and adherence to standards, reminiscent of the natural sciences, became the cornerstone on which the credibility of urban archaeological research rested. Archaeologists not only advocated the value of archaeological fragments but also their expertise in enchaining them effectively.

Some of the ancient fragments uncovered during excavations were left in place in the last decades of the twentieth century. This development culminated in the 1990s with the incorporation of excavated building remains into the Aboa Vetus Ars Nova Museum. Archaeological fragments have gradually become an ordinary and accessible part of the urban landscape. Presently, making them into visible parts of the cityscape is an issue that becomes publicly addressed every time when major archaeological excavations take place in Turku. Fragments are ruins sparking feelings of longing and demands for preservation. An example are the well-preserved cellars discovered during archaeological investigations under the Katedralskolan Gymnasium near the medieval Old Great Square in 2018–2019. The city organized a popular pop-up museum for visitors to explore the ruins, and numerous public pleas were made to leave the structures on permanent display. They were eventually covered with new floor structures (Gustafsson Citation2018; Koskinen Citation2018). The Turku Museum Centre, responsible for managing the urban archaeological heritage, does not have a master plan on how to incorporate such fragments into the urban landscape, but the general policy is to preserve the remains of masonry buildings older than the seventeenth century in situ.

The role of archaeologists has shifted from scholars uncovering knowledge into experts affecting the city’s life. This is evinced, firstly, by the large number of visitors on guided tours and volunteers taking part in archaeological excavations (Aalto Citation2017; Aalto and Mattila Citation2019; City of Turku Citation2018; Runsten Citation2021). Public awareness of the fragments underground has increased, and there are places in the center of Turku where they remain permanently visible. The second indication of the changing role of archaeologists is the development of managerial practices. While fieldwork was outsourced from the Turku Museum Centre, the introduction of the old town concept has given the city’s historicity as well as archaeological fragments an acknowledged position in Turku’s development plans. The enchainment of urban fragments is managed in a more systematic and organized manner. The integration of archaeologists more tightly with land use and heritage management widens the scope of enchainment and accumulation to urban planners and architects, and the variety of stakeholders. However, assessing their roles in the heritagisation of urban fragments, and estimating the effects of changing planning ideals and processes in different zoning and construction projects go beyond the scope of the present article.

The transformation of urban fragments into heritage in Turku shows how the archaeological remains, when left in the cityscape, began to organize the environment into wholes and parts, and how enchainment, by connecting the fragments with the past, allowed individuals and communities to arrange themselves and their identities around the fragments. Heritagisation created novel meanings for the fragments, most importantly it identified them as sources of scholarly information, and thus allowed novel patterns for intangible and tangible heritage to develop. Fragmentation theory emphasizes the materiality of detached pieces, and in Turku, this seems to be characterized by both fragility and disruptiveness of the fragments. They are also qualities that the accumulative approach to fragments in heritage management and urban planning have had to deal with.

Conclusions

The Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape from 2011 amplified the shift from object-based to landscape-based preservation. Although this is a vital improvement in heritage management, it does not invalidate approaching urban heritage as objects. In fact, present-day archaeological theories of material culture do not see objects in the same manner as the object-based approach once did. The study of objects and the study of landscapes complement each other, as the application of fragmentation theory in the analysis of archaeological heritage shows. The theory offers conceptual means to inspect processes which set archaeological remnants together and apart in the cityscape, and define the relationship between heritage institutions, academic research, and urban dwellers. It also shows how fragmentation generates and transforms the intangible aspects of urban heritage. In this concluding section, I will summarize how fragmentation theory can be useful for urban heritage studies.

To be meaningful in the context of urban heritage, fragmentation theory requires revisions. The assumption of fragmentation being solely intentional is not suitable when discussing urban archaeological remains, and thus the emphasis should be put on how the original object is reconstructed or construed and traced back into the past. Another important revision is the realization that fragments carry the potential to be singular bodies even if their itineraries connect them with larger objects. This highlights the ambiguity of the concept of object. Despite these modifications, fragmentation theory remains a powerful tool to describe how pieces of objects are enchained and organized into networks with physical, social, and cultural effects.

The benefits of using fragmentation theory in the study of urban heritage is, firstly, that it brings physical fragments into the core of analysis, uniting tangible and intangible aspects of heritage. Archaeological fragments break the apparent coherence of the modern urban space materially and visually and yet remain enchained to the city and its history. Moreover, the public discourse on cultural heritage is a binding force that enchains not only archaeological fragments but also other forms of cultural heritage, such as built heritage, urban events, and other cultural phenomena, i.e., the urban landscape at large. The original objects of urban archaeological remains are unavoidably vague, and this makes the itineraries of the fragments also flexible. Depending on the fragments, their original wholes, into which they become enchained, can be structures, buildings, cities, and even larger entities, like the past or environmental change. The analysis of urban fragments focuses thus on materiality but expands into other forms of heritage.

Secondly, fragmentation theory calls attention to the temporal structure of objects, fragments, and their heritagisation. In this article, I have analyzed the history of urban fragments in Turku, but their itineraries imply also future trajectories. In the twenty-first century, Finnish urban archaeologists have become accustomed to manoeuvring between fieldwork activities and public engagement (Moilanen et al. Citation2019; cf. Perry Citation2018). Without enchaining, i.e., without access to the original wholeness of fragments, they are easily overlooked in the urban space. Enchainment can be conducted in various ways of which some are institutionalized and accredited to heritage professionals. Archaeology provides skills to work with archaeological remains, to bring them above ground and to engage urban residents with that heritage. One of the future challenges of archaeology is to show that these original objects also include, e.g., the environment and its impact on urban change, which are itineraries relevant also for urban futures. In sum, the analysis of enchainment reveals the itineraries of fragments, which, in turn, contribute to their agency, and such an analysis allows anticipating the forms of future enchainment.

Thirdly, fragmentation theory distinguishes enchainment and accumulation as two ways of engaging with fragments. In urban fragments they both are present, and especially in heritage management they can cause strain manifested in the frustration of archaeologists when scholarly and management concerns collide. Another challenge, which fragmentation theory brings out in urban heritage management, is the acknowledgement of the fragmentary nature of heritage. This refers the essence of archaeological fragments as objects. Beside their heritage value, broken-off pieces have the potential to fragment even further and create diversions in the cityscape. The creative quality of fragments, stemming from their independence, has been less well understood and cherished by archaeologists and heritage management. One step towards tending this self-sufficiency could be to apply fragmentation theory in their study.

Since fragmentation theory does not come with a methodological toolkit, it cannot be applied in urban planning in a standardized manner. However, the theory attunes one to the creative aspects of fragmentation, the agency of fragments, and communicating these as narratives. It connects different aspects, both material and immaterial, and actions related to fragments, and gives a set of interrelated concepts to analyze such an entity. To tap into the narrative and experiential potential of fragments requires that they are seen as fragments, which is not easy in a crowded urban space, but on the other hand, once they become noticed, urban fragments have effects of their own. They do not need to be deemed valuable in an archaeological sense, contextualized with information boards, or made visually more appealing to have an impact.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aalto, I. 2017. “Kadonneiden kivitalojen jäljillä: Katsaus Aboa Vetus & Ars Nova -museon kesän 2017 kaivauksiin.” SKAS 1 (2017): 47–54.

- Aalto, I. 2020. “Possibilities of Public Excavations in the Urban Context.” Fennoscandia archaeologica XXXVII: 147–164.

- Aalto, I., and E. Mattila. 2019. “Puutarha-arkeologiaa yleisön kanssa: Aboa Vetus & Ars Nova -museon kaivaukset 2018.” SKAS 2 (2019): 38–46.

- Appadurai, A., ed. 1986. The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Appelgren, H. 1902. Det underjordiska Åbo. Finskt Museum, 1901, 49–65.

- Bartolini, N. 2014. “Critical Urban Heritage: From Palimpsest to Brecciation.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 20 (5): 519–533. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2013.794855

- Belford, P. 2020. “Some More Equal Than Others? Some Issues for Urban Archaeology in the United Kingdom.” In Managing Archaeology in Dynamic Urban Centres, edited by P. Belford, and J. Bouwmeester, 39–54. Leiden: Sidestone Press.

- Belford, P., and J. Bouwmeester. 2020. “Managing Archaeology in Dynamic Urban Centres: Challenges and Opportunities.” In Managing Archaeology in Dynamic Urban Centres, edited by P. Belford, and J. Bouwmeester, 209–212. Leiden: Sidestone Press.

- Bradshaw, M. 2007. “Native/American Digital Storytelling: Situating the Cherokee Oral Tradition within American Literary History.” Literature Compass 4 (1): 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-4113.2006.00376.x.

- Brittain, M., and O. Harris. 2010. “Enchaining Arguments and Fragmenting Assumptions: Reconsidering the Fragmentation Debate in Archaeology.” World Archaeology 42 (4): 581–594. https://doi.org/10.1080/00438243.2010.518415

- Brusila, H., and N. Lepokorpi. 1981. “Uutta tietoa Turun tuomiokirkon pohjoispuolen maanalaisista rakennusjäljennöksistä.” Turun kaupungin historiallinen museo: Vuosijulkaisu 42–43 (1978–1979): 11–40.

- Chapman, J. 2000. Fragmentation in Archaeology: People, Places and Broken Objects in the Prehistory of South Eastern Europe. London: Routledge.

- Chapman, J. 2013. “Pottery Fragmentation in Archaeology: Picking Up the Pieces.” Annales Universitatis Apulensis Series Historica 17 (II): 7–26. https://doi.org/10.29302/AUASH/article-23

- Chapman, J., and B. Gaydarska. 2006. Parts and Wholes: Fragmentation in Prehistoric Context. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

- The City of Turku. 2018, July 16. Katedralskolanin pop up -museossa vieraili lähes 4500 kävijää. The City of Turku. https://www.turku.fi/uutinen/2018-07-16_katedralskolanin-pop-museossa-vieraili-lahes-4500-kavijaa.

- Colavitti, A. M. 2018. Urban Heritage Management: Planning with History. Cham: Springer.

- DeSilvey, C. 2017. Curated Decay: Heritage Beyond Saving. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

- Ennen, E. 1997. “The Groningen Museum: Urban Heritage in Fragments.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 3 (3): 144–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527259708722201

- Fewster, D. 2006. Visions of Past Glory: Nationalism and the Construction of Early Finnish History. Helsinki: Finnish Literature Society.

- Fewster, D. 2011. “Braves Step Out of the Night of the Barrows’: Regenerating the Heritage of Early Medieval Finland.” In The Uses of the Middle Ages in Modern European States: History, Nationhood and the Search for Origins, edited by R. J. W. Evans, and G. P. Marchal, 31–51. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Fouseki, K., T. S. Guttormsen, and G. Swensen. 2020. “Heritage and Sustainable Urban Transformations: A ‘Deep Cities’ Approach.” In Heritage and Sustainable Urban Transformations: Deep Cities, edited by K. Fouseki, T. S. Guttormsen, and G. Swensen, 1–15. London: Routledge.

- Gamble, C. 2007. Origins and Revolutions: Human Identity in Earliest Prehistory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Gaydarska, B. 2023. “There is Method in Madness: Or How to Approach Fragmentation in Archaeology.” In Broken Bodies, Places and Objects: New Perspectives on Fragmentation in Archaeology, edited by A. Sörman, A. A. Noterman, and M. Fjellström, 103–123. London: Routledge.

- Gustafsson, K. 2018, August 10. Turun Pompeiji kätketään jälleen maan poveen. YLE Uutiset. https://yle.fi/uutiset/3-10347675.

- Guttormsen, T. S. 2020. “Archaeology as a Conceptual Tool in Urban Planning.” In Heritage and Sustainable Urban Transformations: Deep Cities, edited by K. Fouseki, T. S. Guttormsen, and G. Swensen, 35–54. London: Routledge.

- Guttormsen, T. S., and J. Skrede. 2022. “Heritage and Change Management.” In The Routledge Handbook of Sustainable Heritage, edited by K. Fouseki, M. Cassar, G. Dreyfuss, and K. Ang Kah Eng, 30–43. London: Routledge.

- Hänninen, T. 2022. Yleisötyön professio: Turun museokeskuksen yleisötyön määrittely ja selkeyttäminen organisaation sisällä. Unpublished MA Thesis. HUMAK University of Applied Sciences. https://urn.fi/URN:NBN:fi:amk-2022060816739.

- Harrison, R. 2020. “Heritage as Future-Making Practices.” In Heritage Futures: Comparative Approaches to Natural and Cultural Heritage Practices, edited by R. Harrison, C. DeSilvey, C. Holtorf, S. Macdonald, N. Bartolini, E. Breithoff, H. Fredheim, et al., 20–50. London: UCL Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv13xps9m.8

- Immonen, V. 2019. “Tontun karkotus maanalaisesta Turusta.” Kritiikki 1 (2019): 20–24.

- Immonen, V., J. Kinnunen, and J. Harjula. 2022. “At the Fringes of Urbanisation: Developing Socio-Economic Structures and the Founding of the Town of Turku, Finland, c. 1300.” Zeitschrift für Archäologie des Mittelalters 49: 217–234.

- Immonen, V., A. Kivilaakso, M. Mäki, T. Männistö-Funk, P. Pentti, and A. Sivula. 2021. “The Vacillating Sources of Authority: The Case of the Old Town in Turku, Finland.” In Cities in a Changing World: Questions of Culture, Climate and Design, edited by J. Montgomery, 38–46. Amps. https://amps-research.com/proceedings/

- Jauhiainen, J. S. 1997. “Urban development and gentrification in Finland: The Case of Turku.” Scandinavian Housing and Planning Research 14 (2): 71–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/02815739708730423.

- Jokilehto, J. 1998. “International Trends in Historic Preservation: From Ancient Monuments to Living Cultures.” APT Bulletin 29 (3/4): 17–19. https://doi.org/10.2307/1504606

- Jones, A. M., M. Diaz-Guardamino, and R. J. Crellin. 2016. “From Artefact Biographies to ‘Multiple Objects’: A New Analysis of the Decorated Plaques of the Irish Sea Region.” Norwegian Archaeological Review 49 (2): 113–133. https://doi.org/10.1080/00293652.2016.1227359

- Joy, J. 2009. “Reinvigorating Object Biography: Reproducing the Drama of Object Lives.” World Archaeology 41 (4): 540–556. https://doi.org/10.1080/00438240903345530

- Joyce, R. A., and S. D. Gillespie, eds. 2015. Things in Motion: Object Itineraries in Anthropological Practice. Santa Fe, NM: SAR Press.

- Juslenius, D. 1700/2005. Aboa vetus et nova: Vanha ja uusi Turku. Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura.

- Kalpa, H. 2011. Casagrandentalo: Pyhän Hengen kirkosta Pyhän Hengen kappeliin. Kiinteistö oy Casagrandentalo.

- Karimi, K. 2000. “Urban Conservation and Spatial Transformation: Preserving the Fragments or Maintaining the ‘Spatial Spirit’.” Urban Design International 5 (3-4): 221–231. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.udi.9000012

- Keskustavisio. 2017. Keskustavisio: Kaupunkistrategia 2029. Turun kaupunki. https://www.turku.fi/keskustan-kehittaminen/keskustavisio.

- Kirchmair, L. 2023. “Ruin(ed) Policies: Why We Should Aim for Protecting Ruins Regionally.” International Journal of Cultural Policy 29 (2): 202–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/10286632.2022.2036136

- Klami, H. 1982. Turun tauti: Kansanvallan kriisi suomalaisessa ympäristöpolitiikassa. Helsinki: WSOY.

- Koskinen, P. 2018, February 28. “On tämä Suomen mitassa poikkeuksellinen”: Nyt mietitään, miten yhdistää Turun “Pompeji” ja jumppasali. YLE Uutiset. https://yle.fi/uutiset/3-10094224.

- Kostet, J., and A. Pihlman, eds. 1989. Turun Mätäjärvi. Turun maakuntamuseo.

- Lamb, J. 2008. “Unloved Places: An Overlooked Opportunity for Urban Morphology.” Urban Morphology 12 (2): 136–138. https://doi.org/10.51347/jum.v12i2.4506

- Lammassaari, M. 2023, November 9. Lasihelmiä ja nahkakenkiä: Katso kuvagalleria arkeologien löydöistä: “Näin laajasti kaikkein vanhinta Turkua ei ole kaivettu vuosikymmeniin”. YLE Uutiset. https://yle.fi/a/74-20059117.

- Lehto-Vahtera, J., and E. Holkeri, eds. 2012. Aboa Vetus & Ars Nova: Historian ja nykytaiteen museo. Matti Koivurinnan säätiö.

- Mantere, V., and E. A. Kashina. 2020. “Elk-Head Staffs in Prehistoric Northern Europe and Northwestern Russia: Signs of Power and Prestige?” Oxford Journal of Archaeology 39 (1): 2–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/ojoa.12185

- Matsuda, A., and K. Okamura. 2011. “Introduction: New Perspectives in Global Public Archaeology.” In New Perspectives in Global Public Archaeology, edited by K. Okamura, and A. Matsuda, 1–18. Cham: Springer.

- McAtackney, L., and K. Ryzewski. 2017. “Introduction: Contemporary Archaeology and the City: Creativity, Ruination, and Political Action.” In Contemporary Archaeology and the City: Creativity, Ruination, and Political Action, edited by L. McAtackney, and K. Ryzewski, 1–28. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Moilanen, U., J. Jokela, J. Siltainsuu, I. Aalto, A. Koivisto, S. Viljanmaa, and J. Näränen. 2019. “Yleisökaivauksen suunnittelun ja toteutuksen hyvät käytännöt.” Muinaistutkija 3 (2019): 2–17.

- Monckton, L. 2022. “Wellbeing and the Historic Environment: A Strategic Approach.” In Archaeology, Heritage, and Wellbeing: Authentic, Powerful, and Therapeutic Engagement with the Past, edited by P. Everill, and K. Burnell, 239–260. London and New York: Routledge.

- Morton, S. G., J. J. Awe, and D. M. Pendergast. 2019. “Shattered: Object Fragmentation and Social Enchainment in the Eastern Maya Lowlands.” Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 56: 101108–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaa.2019.101108.

- MTV Uutiset. 2019, July 17. Arkeologiset kaivaukset Turussa paljastivat yllättäviä löytöjä satojen vuosien takaa: “Meillä on maanalainen Turku, joka on suuri aarre Suomen kaupunkihistoriassa”. MTV Uutiset. https://www.mtvuutiset.fi/artikkeli/arkeologiset-kaivaukset-turussa-paljastivat-yllattavia-loytoja-satojen-vuosien-takaa-meilla-on-maanalainen-turku-joka-on-suuri-aarre-suomen-kaupunkihistoriassa/7447118.

- OED. 2023. Fragment (n.). Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/OED/6781669731

- Olivier, L. 2011. The Dark Abyss of Time: Archaeology and Memory. Lanham, MD: AltaMira Press.

- Perry, S. 2018. “Why Are Heritage Interpreters Voiceless at the Trowel’s Edge? A Plea for Rewriting the Archaeological Workflow.” Advances in Archaeological Practice 6 (3): 212–227. https://doi.org/10.1017/aap.2018.21

- Pétursdóttir, Þ, and B. Olsen. 2014. “Imaging Modern Decay: The Aesthetics of Ruin Photography.” Journal of Contemporary Archaeology 1 (1): 7–23. https://doi.org/10.1558/jca.v1i1.7

- Ratilainen, T. 2018. “Turun piispojen residenssit.” In Koroinen: Suomen ensimmäinen kirkollinen keskus, edited by J. Harjula, S. Hukantaival, V. Immonen, T. Ratilainen, and K. Salonen, 70. Turun Historiallinen Yhdistys.

- Runsten, K. 2021, November 7. Kaivaukset Turun alle vetävät väkeä: “Keskiaika voi tuntua hirveän kaukaiselta, mutta itse asiassa se ei pidä paikkansa”. Maaseudun Tulevaisuus. https://www.maaseuduntulevaisuus.fi/ihmiset-kulttuuri/artikkeli-1.1628857.

- Saloranta, E. 2019. “Aurajoen rantojen rakentaminen kaupungin vanhalla ydinalueella ennen vuoden 1827 paloa.” Turun museokeskus: Raportteja 23: 96–118.

- Savolainen, P., H. Hannula, and R. Välimäki. 2021. “Milloin Turku perustettiin: Kaupungin historian muistaminen uuden ajan alun historiankirjoituksessa ja tulkinta kaupungin perustamisajankohdasta.” SKAS 1 (2021): 46–60.

- Schaepe, D. M., B. Angelbeck, D. Snook, and J. R. Welch. 2017. “Archaeology as Therapy: Connecting Belongings, Knowledge, Time, Place, and Well-Being.” Current Anthropology 58 (4): 502–533. https://doi.org/10.1086/692985

- Schlegel, F. 1798/1967. Kritische Friedrich Schlegel Ausgabe: Bd 2: Charakteristiken und Kritiken 1 (1796–1801). Munich: Schoningh.

- Schnapp, A. 2018. “What Is a Ruin? The Western Definition.” Know: A Journal on the Formation of Knowledge 2 (1): 155–173. https://doi.org/10.1086/696339

- Schnapp, A. 2020. Une histoire universelle des ruines: Des origines aux lumières. Paris: Éditions du Seuil.

- Seppänen, L. 2020. “The Role of Archaeology and Heritage in Sustainable Urban Planning with Reflections from Turku, Finland.” In Heritage and Sustainable Urban Transformations: Deep Cities, edited by K. Fouseki, T. S. Guttormsen, and G. Swensen, 240–257. London and New York: Routledge.

- Shanks, M. 2012. Archaeological Imagination. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press.

- Sjöstrand, Y. 2010. “Product or Production: On the Accumulative Aspect of Rock Art at Nämforsen, Northern Sweden.” Current Swedish Archaeology 18: 251–269. https://doi.org/10.37718/CSA.2010.15

- Smith, L. 2006. The Uses of Heritage. London and New York: Routledge.

- Sørensen, M. L. S., and D. Viejo-Rose. 2015. “Introduction: The Impact of Conflict on Cultural Heritage: A Biographical Lens.” In War and Cultural Heritage: Biographies of Place, edited by M. L. S. Sørensen, and D. Viejo-Rose, 1–17. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Sörman, A., A. A. Noterman, and M. Fjellström. 2023. “Fragmentation in Archaeological Context: Studying the Incomplete.” In Broken Bodies, Places and Objects: New Perspectives on Fragmentation in Archaeology, edited by A. Sörman, A. A. Noterman, and M. Fjellström, 1–22. London and New York: Routledge.

- Taavitsainen, J.-P. 2003. “Piirteitä Turun arkeologiasta.” In Kaupunkia pintaa syvemmältä: Arkeologisia näkökulmia Turun historiaan, edited by L. Seppänen, 9–24. Turku: TS-Yhtymä and Suomen keskiajan arkeologian seura.

- Turun Sanomat. 2005, October 7. Dominikaanimunkeille muistomerkki Turkuun. Turun Sanomat. https://www.ts.fi/viihde/1074073714.

- Valonen, N. 1958. “Turun viemärikaivantolöydöistä.” Turun kaupungin historiallinen museo: Vuosijulkaisu 20–21 (1956–1957): 12–110.

- van Londen, H. 2016. “Archaeological Heritage Education and the Making of Regional Identities.” In Sensitive Pasts: Questioning Heritage in Education, edited by C. van Boxtel, M. Grever, and S. Klein, 153–170. New York: Berghahn.

- Veldpaus, L., A. R. P. Roders, and B. J. F. Colenbrander. 2013. “Urban Heritage: Putting the Past into the Future.” The Historic Environment: Policy & Practice 4 (1): 3–18. https://doi.org/10.1179/1756750513Z.00000000022.

- Wang, K. 2023. “Time Rupture in Urban Heritage: Based on the Case of Shanghai.” GeoJournal 88: 1965–1977. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-022-10732-2.

- Warnaby, G. 2019. “Of Time and the City: Curating Urban Fragments for the Purposes of Place Marketing.” Journal of Place Management and Development 12 (2): 181–196. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPMD-08-2018-0063

- Willems, W. J. H. 1998. “Archaeology and Heritage Management in Europe: Trends and Developments.” European Journal of Archaeology 1 (3): 293–311. https://doi.org/10.1179/eja.1998.1.3.293

- Williams, T. D. 2014. “Archaeology: Reading the City through Time.” In Reconnecting the City: The Historic Urban Landscape Approach and the Future of Urban Heritage, edited by F. Bandarin, and R. van Oers, 19–46. Chicehster: Wiley-Blackwell.