ABSTRACT

In this article, we explore transformation photos on Instagram as ‘digital artefacts’ that can inform understandings of eating disorder recovery in the context of sport, exercise and health. Transformation photos are two images (from different time points) set alongside one another to represent the changing of bodies in look, shape or size. These images are prevalent within eating disorder recovery and fitness spaces on Instagram and typically display an individual’s recovery journey through a before (thin) and after (more muscular) image comparison. By triangulating interview, photo elicitation and netnography data from research on female weightlifting as a tool for recovery from eating disorders, we explore transformation photos in relation to three intersecting themes; 1) new modes of ‘becoming’, 2) representation and ‘mediated memories’, and finally, 3) survivorship and identity. Our findings demonstrate that transformation photos are integral to the process and practice of recovery for women who use weightlifting as a tool for recovery from eating disorders. Moreover, we suggest that by engaging with a popular mimetic device (transformation photos), we were able to ‘meet participants where they are’ and offer a novel qualitative approach to understanding how digitally mediated lives are lived.

Introduction

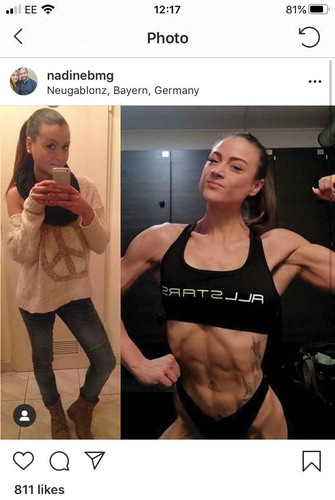

In this paper, we explore transformation photos as ‘digital artefacts’ which inform our understandings of eating disorder recovery in the context of sport, exercise and health. Transformation photos exist in a multiplicity of forms, however they are typically recognisable according to a specific set of shared traits. In principle, transformation photos are two images (from different time points) set alongside one another to represent the changing of bodies in look, shape or size (Vogel, Rose, and Crane Citation2018). Images that exist in this format are used in a variety of contexts, for example, to show changes in bodies as a result of weight loss, surgery, makeovers/aesthetic improvements, and pregnancy. In this article, we focus specifically on transformation photos that depict the use of weightlifting as a strategy for recovery from eating disorders. These images are prevalent within eating disorder recovery and fitness spaces on Instagram and typically display an individual’s recovery journey through a before (thin) and after (more muscular) image comparison (see ).

Table 1. Interview participants

Transformation photos have received little focused attention from academic enquiry, however there has been some mention of these images in the context of weight-loss blogging (Leggatt‐Cook and Chamberlain Citation2012), the psychology of social support on social media (Vogel, Rose, and Crane Citation2018), and of particular interest to this study, in the context of eating disorder recovery communities on Instagram (LaMarre and Rice Citation2017). These images are also commonly observable within online networks with a focus on sport, exercise and health, and therefore offer interesting insights with regards to how individuals come to understand their bodies and health practices through the lens of digitally mediated images. However, to our knowledge, there are no studies that explore the meanings associated with transformation photos from the perspective of the individuals who post them and as digital artefacts that have proliferated concurrently with the advent of social media. Moreover, transformation photos are integral to the process and practice of recovery for women who use weightlifting as a tool for recovery from eating disorders and therefore warrant further investigation in this context.

As this paper is centred on such a profoundly visual phenomena, three transformation photos (see , & ) have been selected to illustrate the argument that follows. These images (taken from Instagram) are intended to contextualise our overall argument as well as communicate aspects of our analysis. The images included throughout are not of the same individuals who took part in interviews but are instead ‘found’ images from the netnography phase of the research. Author 1 gained informed consent from Instagram account holders to use these images. When communicating with the account holders it became apparent that they wanted to be given credit for the content they were creating and asked to have their usernames included in this article. The ethics attached to this process are explored in further detail in the methods section.

In what follows, we point to the extant work already conducted on women’s bodies, health, and the digital. We then align transformation photos with sociological literature on the body as ‘becoming’ as well as extant feminist work which theoretically troubles cultural appetites for the reinvention of feminine subjectivity. Following this, we outline our methods, which involve the triangulation of multiple rich data sets. Our findings focus on three key themes; 1) new modes of ‘becoming’, 2) representation and ‘mediated memories’, and 3) survivorship and identity. Finally, in our discussion, we examine transformation photos as a mimetic device which have garnered popularity in a neoliberal socio-cultural climate and draw attention to the wider implications associated with communicating about recovery, bodies, and mental health in this way.

Literature review

Health, bodies and the digital

As the digital becomes further embedded in lifestyle practices, the influence of mobile technologies on everyday understandings of health and bodies cannot be underestimated (Rich and Miah Citation2014). Scholars have explored this interplay in relation to the quantification of health-seeking practices (Lupton Citation2016), social media fitness communities (Camacho-Miñano, MacIsaac, and Rich Citation2019; Jong and Drummond Citation2016), and health-related apps and wearable devices (Eikey and Reddy Citation2017; Goodyear, Armour, and Wood Citation2019). Within this body of work, the digital is framed as a source of ‘public pedagogy’ regarding health-seeking practices, which shapes social understandings of gendered bodies and their capabilities (Camacho-Miñano, MacIsaac, and Rich Citation2019; Rich and Miah Citation2014). In particular, since the advent of social media, female-dominated health and fitness spaces online have been subject to sustained academic interest. Much of this literature critiques the ways in which female members of these communities are encouraged to take up personal responsibility for disciplining their bodies in service of a specific physical ideal (Riley and Evans Citation2018). This kind of discourse is characterised as ‘healthism’, defined here as a ‘colonising narrative that emphasises individual responsibility for health and wellbeing’ (Fox, Ward, and O’Rourke Citation2005, 947). In this regard, within these female-dominated online spaces time and resource intensive activities are framed as leisure practices that are integral to living a healthy and responsible lifestyle (Jong and Drummond Citation2016).

Of these healthism discourses, perhaps the most written about are ‘thinspiration’ (images that promote the thin ideal) and ‘fitspiration’ (images that promote the achievement of a lean body-type through exercise) (Alberga, Withnell, and von Ranson Citation2018). The seemingly high prevalence of these images within the social media landscape has led to a great deal of scholarship which examines the impact of thinspiration/fitspiration on women’s wellbeing (Griffiths and Stefanovski Citation2019). Research in this area reveals that ‘exposure’ to thinspiration/fitspiration messaging predicts a range of harmful effects, such as greater body dissatisfaction and negative mood (Tiggemann and Zaccardo Citation2015; Prichard et al. Citation2017). Furthermore, models have been developed which attempt to link eating disorder symptomology to the viewing of these images (Griffiths et al. Citation2018). This is significant, as it could be argued that transformation photos and ‘fitspiration’ messaging both promote the attainment of health and happiness through exercise and therefore share some characteristics. Moreover, transformation photos depicting recovery from eating disorders through weightlifting visually mirror cultural shifts from the thin ideal to a more muscular and fit ideal body (Tiggemann and Zaccardo Citation2015).

While transformation photos connect to literature on healthism discourses and online fitness communities, there is also a profoundly therapeutic element to these images which aligns with literature on digital articulations of mental health, pain and recovery. Scholars in this field have traced the ways that mental ill health is enacted and rendered knowable through discursive and mimetic strategies performed on social media (Fullagar et al. Citation2017; Holmes Citation2017; Dobson Citation2015). Fullagar et al. (Citation2017) terms these kinds of online networks ‘therapeutic publics’, which are defined here as affective arrangements whereby members ‘generate support in anonymous and public ways, offer help, advice to others with daily struggles and raise awareness to combat stigma and discrimination’ (Citation2017, 8). It is noteworthy that, in the past two decades, a great deal of work on digital therapeutic publics has focused on pro-eating disorder (pro-ED) communities, many of which existed before the advent of social media (Fox, Ward, and O’Rourke Citation2005; Bell Citation2009; Dias Citation2013). The sustained fascination with pro-ED spaces online is due to a range of factors, including the fetishisation of starvation as a form of embodied resistance (Holmes Citation2017), and an interest in the counter-medical models of care they display (Fox, Ward, and O’Rourke Citation2005).

Conversely, there is a smaller body of work on recovery communities (LaMarre and Rice Citation2017), and their occasional overlap with pro-ED spaces (Chancellor, Mitra, and De Choudhury Citation2016). Of this literature, Holmes (Citation2017) work on girls’ production of eating disorder recovery narratives in YouTube videos is significant, as it represents another highly specific and stylised communicative tool through which women narrate their experiences with eating disorders. Moreover, in this work, Holmes references the significance of transformation photos to this population. When comparing transformation photos to YouTube videos, she writes, ‘as opposed to the stark contrast between “before” and “after” pictures historically used to image anorexic bodies … we are asked in these videos to bear witness to the gradual emaciation of the body, day by day, pound by pound’ (Citation2017, 15). In this respect, transformation photos are a unique and largely unexplored phenomenon, and yet are key to understanding how women in recovery come to understand their bodies through recovery and give meaning to this process.

Bodies as ‘becoming’ and the makeover paradigm

While transformation photos are yet to be theorised within scholarship, a great deal of theoretical work has been conducted within the sociology of the body which conceptualises the body as in a process of ‘becoming’. Deleuze and Guattari, who were perhaps among the first scholars to write about materiality in this way, conceive of becoming as ‘radical immanence’ and the dynamic movement towards a given state, without pausing or arriving. They write, ‘what is real is the becoming itself, the block of becoming, not the supposedly fixed terms through which that which becomes passes’ (Citation2000, 238). Thinking of bodies in this way, as processual and in a state of flux, proliferates within modern theorising on embodiment. In particular, the logic of becoming has been mobilised by feminist scholars to ‘solve’, or at least neutralise, the dichotomy between materiality and representation (Budgeon Citation2003; Coleman Citation2008; McNay Citation1999). Of this productive framework for understanding the body, McNay writes, ‘as the point of overlap between the physical, the symbolic and the sociological, the body is a dynamic, mutable frontier. The body is the threshold through which the subject’s lived experience of the world is incorporated and realised and, as such, is neither pure object nor pure subject’ (Citation1999, 98). In this respect, the liminal nature of the body has become integral to efforts to move beyond restrictive and dichotomous categories such as materiality/representation, object/subject, and body/image.

Moreover, a great deal of sociological work has attempted to capture, not only the inherent dynamism of the body, but broader neoliberal cultural appetites for harnessing the body’s mutability. The most prolific of such accounts is perhaps Shilling’s (Citation1993) work on ‘body projects’. Shilling attests, ‘in the affluent West, there is a tendency for the body to be seen as an entity which is in the process of becoming; a project which should be worked at and accomplished as part of an individual’s self-identity’ (Citation1993, 4–5). In this respect, becoming can be conceived of, not only a theoretical tool, but as a cultural sensibility. Likewise, Giddens (Citation1991) argues that late modernity is characterised by ‘ontological insecurity’ which has given rise to a growing anxiety regarding identity. This has resulted in the widespread pursuit of a ‘coherent and viable sense of self-identity through attention to the body, particularly the body’s surface’ (Gill, Henwood, and McLean Citation2005, 40). These theoretical ideas are prevalent within qualitative literature on contemporary physical culture, particularly in relation to literature on weightlifting, bodybuilding and the gym (Brace-Govan Citation2002; Gill, Henwood, and McLean Citation2005).

Feminist researchers writing on aesthetic labour and ‘body projects’, suggest that cultural sensibilities for the ‘becoming’ of bodies are highly gendered. In this regard, Gill’s (Citation2007) concept of the ‘makeover paradigm’ (sometimes referred to as the ‘transformation imperative’) describes ideal femininity in postmodern times whereby ‘successful’ feminine subjects are encouraged to engage in constant self-work in order to fix or improve a fundamentally flawed selfhood (Gill Citation2007). Gill writes, ‘this requires people (predominantly women) to believe, first, that they or their life is lacking or flawed in some way; second, that it is amenable to reinvention or transformation by following the advice of relationship, design or lifestyle experts’ (Citation2007, 156). Culturally, this appetite for reinvention is most saliently observable on makeover shows (such as Revenge Body with Khloe Kardashian), as well as at the higher echelons of celebrity culture, whereby women are required to make themselves anew to stay relevant and desirable (Heyes Citation2007). Some salient examples within this sphere include; Madonna, Lady Gaga, and Beyoncé, all of whom have existed in multiple iterations. Appetites for reinvention are therefore highly gendered, however little is known about how feminine subjects themselves conceptualise these embodied projects.

While bodies as becoming and the ‘makeover paradigm’ have been written about and problematised extensively in relation to aesthetic transformations broadly, these frameworks are rarely extended to research on health or ED recovery. Yet, transformation photos that depict recovery through weight-gain could be said to be subverting the negative paradigm in which transformations of the body are typically situated, by reorienting body projects towards positive health and wellbeing. In what follows, we mobilise a novel methodological approach to qualitatively engage with transformation photos as mimetic devices which communicate women’s experiences of using weightlifting as a tool for recovery from eating disorders. Our primary research questions are:

What do transformation photos on Instagram mean to women who are weightlifting in recovery from eating disorders?

What is it about the current socio-political moment that makes transformation photos a popular digital artefact?

Methods

The data for this paper comes from a wider project on women’s use of weightlifting as a strategy for recovery from eating disorders. For this study, semi-structured in-depth interviews, photo elicitation and netnography were deployed and data from each of these methods was triangulated and synthesised to provide a holistic picture of this phenomenon. Throughout the project, Instagram acted as an integral field-site within which much of the recruitment, communication with participants, data collection and analysis took place. To facilitate these key methodological stages, Author 1 [name changed to maintain the integrity of the review process] created an alias account on Instagram, @anonymous [name changed to maintain the integrity of the review process], through which all online aspects of the research took place. Author 1 took the lead on the digital elements of the project due to having somewhat of an ‘insider’ status by nature of her continued participation in amateur weightlifting and history of casual engagement with health and fitness content on social media. Author 1’s prior knowledge and experience were highly valuable when engaging with the subcultural norms and values within Instagram fitness and recovery spaces, as well as the more technical aspects of weightlifting as a sport. Authors 2 and 3 did not have the same ‘insider’ status in the world of amateur weightlifting or fitness social media as author 1 as neither had engaged with amateur weightlifting previously. Authors 2 and 3, both women and self-defined feminists, have backgrounds in sociology of sport, gender and the body.

Recruitment

Female participants, aged 17 and over, living in the UK, who have a history of eating disorders and are weightlifting during their recovery, were sought to take part in the study (see ) and a two-pronged (online/offline) approach to sampling was used. Firstly, the study was advertised on posters and flyers in a selected group of gyms in England. Recruitment through gyms and word of mouth yielded 10 participants out of a total sample of n = 19. It is noteworthy that, while this subsample was recruited offline, upon meeting participants for interview it transpired that many of these women also use Instagram to document their recovery and either post transformation photos themselves or regularly engage with them in their social media use.

Secondly, calls for participants were posted on the alias Instagram account and the authors’ Twitter accounts. A targeted approach was also taken on Instagram, to identify and contact individuals who appeared to fit the study criteria. This process of recruitment via Instagram is particularly pertinent to the subject matter of this paper, as individuals were often identified as potentially suitable to take part in the research by virtue of the presence of transformation photos on their account. During the recruitment phase of the study (approximately 6 months) Author 1 searched ‘#edrecovery’ and ‘#gainingweightiscool’ on Instagram through the alias account. This selection of hashtags was based upon Author 1’s prior knowledge of these online spaces. The hashtag #edrecovery is a popular way for individuals on social networking sites to identify themselves as in recovery from an eating disorder and connect to the ED recovery online community (LaMarre and Rice Citation2017). The hashtag #gainingweightiscool is often found within both fitness and ED recovery spaces on social media and is attached to content about weight-gain, which is often (though not always) depicted as achieved through muscle-building. When searching both hashtags respectively, Author 1 scrolled through the ‘top’ and ‘most recent’ posts on Instagram looking for transformation photos that may signify the use of weightlifting as a tool for recovery from eating disorders. The presence of transformation photos, particularly when the ‘after’ photo showed the person in gym clothes or ‘flexing’ (see ), was a key indicator of this experience.

Once potential participants were identified, Author 1 visited the content author’s Instagram profile to search for further indications that would confirm the individual was using weightlifting as a mode of recovery from eating disorders. The most common evidence for this came in the form of text captions below transformation photos, where the account holder explained their transition from an eating disorder to weightlifting. On other occasions, the existence of the hashtags ‘#edrecovery’ or ‘#recoverywarrior’ beneath images of women in the gym or ‘flexing’ in gym wear was sufficient to justify initial contact. In total, 68 women were identified as potentially fitting the study criteria and direct messaged from the alias Instagram account with information about the study. A total of 9 participants were secured using this online recruitment method.

A limitation of the recruitment method described above is that women recruited through social media were sometimes identified and contacted according to the visibility of their recovery. This occularcentric approach may therefore have excluded others whose recovery does not fit within this dominant framing due to the absence of any visible transformation of the body. However, for the purposes of this paper (which is concerned with a specific and highly visual method of representing embodied processes of ‘becoming’) an occularcentric line of enquiry provides access to individuals who are adept in communicating in this manner.

The ethics attached to ‘cold’ contacting women over social media was discussed at length among the authors of this paper, due to the increasingly blurred boundaries between public and private online information (Morrow, Hawkins, and Kern Citation2015). In response to shared concerns that contacting women about such a sensitive topic might be considered invasive or exposing, efforts were made to participate in and engage with online communities through the alias Instagram account (Bluteau Citation2019). To this end, both personal and study-related content was posted by Author 1 to the alias account. This content included; photos of Author 1, information on the study, and journal-style posts on daily life as a researcher. In doing so, we sought to make ourselves (and the research) visible, as well as engage with the concept of ‘virtual-material positionality’ which encourages digital researchers to ‘be more intentional about positionality by opening themselves and their research processes up to the same conditions of transparency, vulnerability, and scrutiny as their online research participants’ (Morrow, Hawkins, and Kern Citation2015, 538). It is perhaps interesting to mention here that, while many women did not respond to the initial message or declined to take part, none expressed concern for their privacy or asked how Author 1 came about their account. It could be hypothesised that women within ED recovery and fitness spaces are somewhat accepting of their visibility online.

Data collection

To ensure rigour, a multi-methodological approach was utilised to explore women’s experiences using weightlifting as a tool for recovery. Firstly, in-depth interviews were conducted longitudinally by Author 1; three with each participant, scheduled at four monthly intervals. Interviews were semi-structured, each lasting between 45 minutes and 1.5 hours, with the exception of the third and final interview, which was more often a 20–30 minute conversation over phone/video call or email/messenger app. A longitudinal method was adopted in order to capture the messy, often non-linear nature of recovery, as well as a sense of the body in process (Patching and Lawler Citation2009). The interview guide was split into three experiential categories; 1) weightlifting and strength, 2) eating disorder recovery, and 3) social media usage. Five to ten questions were drafted for each category to prompt discussion; however, interviews rarely followed a neat or systematic format. Examples of the kinds of questions asked included; ‘how do you feel when you are weightlifting?’, ‘what does recovery mean to you?’, and ‘what role (if any) does social media play in your life?’.

The second method mobilised was photo elicitation. Participants were asked to bring up to 10 photos of people, objects and places that they associated with recovery to the first interview. In every case, participants shared images from their phones, many of which were screenshots of social media content. Photos were later sent to Author 1 over email or messenger and securely stored. Photo elicitation aided the interview process by ‘breaking the ice’, prompting memory and helping establish a sense of shared understanding between interviewer and participant (Radley and Taylor Citation2003). It is perhaps unsurprising, given the primacy of transformation photos within online recovery/fitness spaces and interview subject matter, that participants frequently shared transformation photos during the photo elicitation phase of the research. In this context, transformation photos were used as a narrative device to convey experiences of mental and physical transition.

The authors working on the project met regularly in order to ensure synergy of analysis. Following the first round of interviews and the photo elicitation exercise, ‘transformations of the body’ emerged as a key theme, as women were highly attuned to the weight, size and shape of their body throughout their recovery journeys and regularly used transformation photos to communicate this experience. As this finding was particularly salient, we wanted to understand in greater depth what transformation photos mean to women using weightlifting in recovery from eating disorders. Therefore, in the second and third round of interviews, participants were asked directly for their thoughts and opinions about transformation photos and, where appropriate, about their personal engagement with this representational practice.

The third and final method used in this study was netnography. Netnography is a method which applies an ethnographic approach to online environments (Kozinets, Dolbec, and Earley Citation2014). For the purposes of this study, the netnography phase allowed for the exploration of ED recovery and fitness communities on Instagram, paying particular attention to the circulation of images, the language/emoji use, and the kinds of discourses that are performed within these subcultures. Observational netnography data collected on Instagram included; images and the associated ‘likes’, captions and comments (including the hashtags) below posts and Instagram ‘stories’. This data was captured through ‘screenshots’ and observational field notes. It is noteworthy that, while our interview and photo elicitation sample were UK-based, Instagram is not a nationally bounded space and therefore data was collected from both UK and non-UK user accounts.

Just as in the first semi-structured interviews and photo elicitation, transformation photos emerged consistently during the netnography phase of the research. These mimetic devices are produced in high numbers within ED recovery and fitness communities online and which are often attached to hashtags (for example #gainingweightiscool and #transformationtuesday) implying some kind of transformation or becoming of the body is taking place. Once the subcultural significance of this representational practice was identified from the interviews, photo elicitation and initial phases of the netnography, a more targeted exploration took place in which transformation photos were actively sought out. In this regard, as Caliandro advocates, we followed ‘the circulation of an empirical object within a given online environment … observing the specific social formations emerging around it from the interactions of digital devices and users’ (Citation2017, 560). Thus, through the alias Instagram account and the mobilisation of relevant hashtags (e.g. #gainingweightiscool) we intentionally collected data relating to transformation photos as an ‘object on the move’ (Caliandro Citation2017, 570).

Ethics

Due to the sensitive nature of the research topic, ethical considerations were embedded in the study’s design. Firstly, ethical approval was gained from the host institution. Interview participants were provided with consent forms and information sheets about the study before any data was collected and care was taken to ensure participants understood what the research was about, how their data would be used, and that they could be signposted towards resources for support (such as eating disorder helplines) should they need to access them. For the purposes of this study, any participants aged 16 and over (two were 17 years of age) were considered young adults and able to independently consent to participation (Goredema-Braid Citation2010). As the study progressed, younger participants were not found to have any additional needs and did not present any exceptional ethical challenges. Pseudonyms were assigned by Author 1 using a random name generator to protect the participants’ anonymity.

Interview participants were given the option to consent for their photo elicitation images to be used for analysis only or for analysis and for use in outputs. Some opted for analysis only, to protect their anonymity and others consented for their photos to be used in outputs, however we were conscious that images that included faces (such as transformation photos) would compromise their anonymity. Moreover, some of the transformation photos we had consent to use in outputs were too low-quality (pixelated) to publish. For these reasons, and because we had informed consent to use a number of good quality images from the netnogrophy, the images in this article are from the netnography only and do not feature any of the interview participants.

A slightly modified ethical approach was adopted for the netnography, as there was no sustained interaction with ‘participants’ during this phase and the data collected took the form of ‘one off’ Instagram captions or images. A selection of these captions and images are included below due to being particularly illustrative of the netnography findings. As with the images presented in this paper, Author 1 contacted account holders over Instagram (direct message) to gain informed consent before using their caption in this article. During such correspondences, we specified which caption we wanted to use, explained the topic of the article and made clear our intention that this text would be published in an academic journal. We also gave the option for account holders to have their usernames included or excluded alongside the caption. Without exception, women opted for their usernames to be included. In meetings regarding the ethics of this project, we discussed removing the Instagram usernames from all images and captions to make them less identifiable. Our main concern with this, however, was that the women we contacted were keen for us to acknowledge them in our research. Therefore, to obscure their account or image would be to go against how they themselves wanted their content to be represented.

Analysis

Analysis for this paper spanned across three rich qualitative data sets, containing both visual and text-based materials. When conducting research using visual data, images are generally conceptualised as either ‘topic’ or ‘resource’ (Harrison Citation2002). This study approaches visual data as both. This is because transformation photos are both the subject of investigation and are used as a lens to better understand a predefined subject matter (i.e. weightlifting during recovery). Therefore, transformation photos were analysed in terms of style, form and content, as well as used as reference points around which the text-based data cohere. Interview and netnography data were analysed using Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis (IPA), which asks the question ‘what is this kind of experience like?’ (Shinebourne and Smith Citation2009). At its core, IPA is a method of analysis which foregrounds experience, subjectivity and relatedness, which are central to the research questions for this paper.

By triangulating these data sets, we provide a nuanced and thorough account of transformation photos by detailing their subjective meaning for a specific group, as well as their wider cultural significance. It is noteworthy to add that these data sets have been combined in the findings intentionally, to convey the notion that online and offline lives are not ontologically separable but are profoundly entangled. In this respect, we contend that posting on social media is not merely an act of self-presentation but also a strategy for participation in culture, community and social life (Caliandro Citation2017). As Caliandro asserts, ‘through self-presentation, users convey a public image of themselves that is constructed on a repertoire of symbols that they deem to be widely shared and valued’, therefore we can use these visual metaphors to ‘reconstruct the collectively built and shared cultural structure’ (Citation2017, 566).

To develop the three themes examined in the findings, we followed the three stages of IPA as described by Smith, Flowers, and Larkin (Citation2009). The first stage of analysis involved ‘initial noting’. This was primarily conducted by Author 1, who wrote down their first impressions of the data as they worked through it. During this process, the following questions acted as prompts; ‘what is being described?’, ‘what kind of language is used?’, and ‘what (at surface-level) is being communicated?’. The second phase focussed on accessing a deeper level of meaning by establishing patterns such as commonly used metaphors and the repetition of language. Here, themes such as ‘#gainingweightiscool’, which was both referred to during interviews as well as used online, began to emerge. The third phase operated at the conceptual level whereby Author 1 identified processes of meaning-making and overarching themes. These themes were subsequently refined and mapped out according to their interconnectedness. As lead on this project, Author 1 conducted most of the analysis and met regularly with the other two authors working on the project in order to ensure rigour and synergy of analysis.

This study is underpinned by a feminist epistemology, whereby knowledge is conceived of as partial and situated (Haraway Citation1988). In this respect, while the ethos of IPA is to get as close to the participants’ viewpoint as possible, researchers, who hold their own subjective and experience-informed perceptions, will inevitably bring to bear their own conceptions of the data. In an effort to, as much as possible, clearly demarcate the participant voice from the researchers’, the findings deal with transformation photos primarily from the point of view of the participants’ and the discussion that follows offers the authors’ interpretation. Moreover, in line with our commitment to recognising knowledge is subjective and inextricably enmeshed with personal experience, values, culture, and privilege, at multiple junctures we attempt to mindfully engage with our own positionality through reflexive practice.

Findings

#gainingweightiscool: new modes of ‘becoming’

For women weightlifting in recovery from eating disorders, transformation photos provided access to new modes of ‘becoming’. For some, engaging with these images on Instagram encouraged women to start weightlifting to begin with, by making alternative modes of embodiment possible and even desirable. As Polly explained:

Looking on other people’s Instagram accounts, there’s lots of like transformation photos of people who have used fitness and that really encouraged me. That was like what made me decide to go into strength training because I saw that people are gaining weight and they look fine, I like how they look … um and there’s lots of hashtags like #gainingweightiscool that is just so refreshing to see that. People seeing gaining weight as a positive thing when you’re recovering (Polly, 17 years old, in recovery from anorexia)

Here, representations of female strength and muscularity offer a third alternative to the perceived fat vs thin dichotomy (Steinem Citation1994). In this respect, while the thin ideal is understood to have negative physical and psychological ramifications for women in recovery (Kroon Van Diest and Perez Citation2013), fat is a stigmatised identity which is perceived to be equally undesirable (Norman and Moola Citation2019). Weight-gain through muscle-building, however, presents as a viable third option for women in recovery. In this sense, normalising and providing access to strong, sporting bodies expands the parameters for feminine embodiment. This is significant, because women have historically been denied access to experiences of strength due to restrictive gender norms and physical ideals (Brace-Govan Citation2004). As Brabazon writes, ‘women learn weakness. We can learn strength by encouraging physical movement, coordination and fitness’ (Citation2006, 76).

The power associated with seeing different kinds of sporting bodies online emerged as a consistent theme during the interviews. As Lily and Maddy expressed:

Instagram was one of the places I was looking at strong people … seeing someone happier who isn’t skinny, which … I thought I had to be [skinny] or fat. Seeing a different type of body and recognising it as something I would like to do. And I guess the more I started to do the weights I started to feel a bit more confident in the fact that I could go in the weights section and seeing the weights go up and lifting more and more. (Lily, 22 years old, in recovery from anorexia)

I do think that recovery and transformation pictures can be so powerful. Like, people seeing someone that looks bigger than they did before and deciding that that is a goal, is kind of revolutionary for some people (Maddy, 21 years old, in recovery from EDNOS)

Here, transformation photos within the digital landscape broaden the scope for understandings of female bodies and their capabilities, offering new modes of ‘becoming’ for women in recovery. While eating disorders can themselves be conceptualised as embodied projects which suspend women and girls in a liminal state of being (Brain Citation2002), transformation photos depicting muscle-building and the pursuit of strength offer a diversion from this path. In this sense, transformation photos within recovery subcultures on social media, introduce weightlifting as an informal tool for recovery and provide the framework for engagement with a different (yet similarly productive) embodied state.

Among women who have taken-up weightlifting as a vehicle for recovery, transformation photos are created and shared between members of online communities. The quote below (taken from a transformation photo caption on Instagram) demonstrates how these images are used to share experiences, celebrate progress, and motivate others:

Just a friendly reminder that weighing less does not make you happier (stop girl emoji)

Life doesn’t start when you’re thinner, lighter, your abs are out, or you can see a smaller number on the scales. Life starts when you stop giving so much mental energy to stressing over what you weigh, and spend more time enjoying what you love (star emoji)

5 years difference, 3 stone heavier, 100 times happier (praise emoji)

#gainingweightiscool #beforeandafter #weightgain #l4l #transformation #throwback # tbt #f4f #bodyimage #training #gym #weights #personaltrainer #pt #training #5yearsago #ditchthescale #dietculture #legs #abs #motivation (@erinkatie.pt)

The mobilisation of hashtags such as ‘#gainingweightiscool’, which has been used on Instagram 152,000 times (as of January 2020), attaches individual auto-ethnographic content to embodied experiences also shared by others. By posting images that follow a particular set of stylistic conventions, women signal their belonging to the subcultural ‘therapeutic public’ of women who weightlift in recovery from eating disorders (Fullagar et al. Citation2017).

Representation and ‘mediated memories’

While the women in this study regularly engaged with transformation photos through their personal social media use, they were highly attuned to discourses on social media that problematise this method of storytelling. The netnography revealed that critiques of transformation photos are particularly prevalent within body positive subcultures on Instagram, which overlap considerably with ED recovery and fitness spaces. For example, in an Instagram post for Eating Disorders Awareness Week, body image researcher, Nadia Craddock, writes:

Let’s start with the side-by-side before & after eating [disorder] pictures. You know, the sad, emaciated, underwear (?) photo (left) and the happy, glossy, but *still thin*, photo (right) posts that scream (speaking emoji) look how sick I was and now look (speaking emoji) everything is glossy and A-MAZ-ING … the ‘before’ images can serve as a goalpost for people struggling: “I don’t deserve help because I don’t look like that/when I look like that, then I will seek help and recovery can begin”. They can reinforce what an eating disorder looks like and can make recovery itself look like a goal … (@nadia.craddock)

The women interviewed for this study were conscious of the image-centred nature of transformation photos and the potential limitations in conveying their recovery journeys in this manner. As a result, they were keen to explain how this representational practice also depicts ‘mental transformation’. As Sarah and Maddy contend:

I take them because I feel good about myself and I feel strong and it’s not in a way that I am … obviously I’m documenting my journey but it’s not like ‘Oh gosh has my body changed or has this changed’ or a visual thing, it’s just I feel good in myself, I want to share that, thank you- post! (Sarah, 18 years old, in recovery from anorexia)

I think everyone is becoming a lot more self-aware when it comes to transformation photos … now they’re either caveated by shitloads of ‘well I’ve made loads of mental gains’ or they’re like … I don’t know, I just think they’re much more justified now. Or they are basically not transformation photos, they’re mental transformation photos with pictures alongside them. Which I think is really good that we talk about the impact of exercise (Maddy, 21 years old, in recovery from EDNOS)

Here, Sarah and Maddy suggest that the meanings associated with transformation photos extend beyond what is captured within a side by side image. This brings us to the semiotics of transformation photos and the specific connotations they hold within the overlapping online subcultures of ED recovery and female weightlifting.

Social media provides a digital platform from which one can externalise individual constructions of selfhood. In this respect, van Doorn writes, ‘memory is never merely private/personal or public/cultural but mediates between these spheres as it appropriates and invests itself in objects that “externalize” memories, transforming them in the process … embodied memory is extended through the everyday practice of producing “mediated memories”’ (Citation2011, 539). In this regard, while experiences of recovery and weightlifting are embodied and subjectively experienced, Instagram provides an external structure from which material practices of ‘becoming’ can be narrativised and communicated to form ‘mediated memories’. Transformation photos, specifically, were identified by this population of women as the site of this kind of activity. As this field note from the netnography depicts:

Posts of food or the gym tend to be accompanied by everyday journal-style entries about appetite or how well a workout went. Transformation photos, however, are often framed by captions which talk much more generally about past experiences and how these have informed how women feel about their bodies and the trajectory of their lives (field note)

Transformation photos thus act as a conduit through which individuals can reflect on and make sense of their experiences. As Lily explained:

I never really talk about my eating disorder at all unless I do the occasional transformation kind of thing. I just like to see … when I look back at what I used to look like and what I look like now it helps me be like ‘ok I am going in the right direction and other people can see it’. And this is what I’ve used this sport for … (Lily, 22 years old, in recovery from anorexia)

The significance of embodied memory to the construction of eating disorder and recovery narratives has been noted by other qualitative work in this field (Eli Citation2016; Warin Citation2010). For participants in this study, ‘mediated memories’ emerged consistently as a motivating factor for a successful and sustained recovery. Viewing images of old selves was reported to prompt feelings of pride, positive self-esteem and achievement. As Ibrahim contends, ‘photographic images act as an aide memoir or as a “trigger” to memory. They become the material repositories that allow people to engage in forms of “memory work” that is both individual and collective, enabling appropriations of both time and space’ (Citation2015, 44). In this respect, the women in this study engage with Instagram as an autoethnographic project, which allows them to piece together a coherent narrative to make sense of past experiences.

Survivorship and identity

It is significant that transformation photos, and the captions that accompany them, typically follow an upward trajectory and are framed as journeys of growth, survivorship and self-actualisation. These themes resounded across the interviews, photo elicitation and netnography, in connection to transformation photos and are also reflected in the typical style of the images (see ). In the ‘before’ photo, women often look downcast as they inspect their bodies in the mirror. In the ‘after’ photo, women tend to stand tall with their shoulders back and a happy/contented expression.

As the Instagram caption below (taken from a transformation photo) demonstrates:

11 months difference. Left (hand sign) miserable, controlled by my eating disorder. No sense of identity. Right (hand sign) happiest I’ve been in years, living life. “Healthy”. Strong. Resilient. About to start a dream job (praying sign, love heart) My recovery and ED has spanned all of my adult life. But I am so so proud to say I am finally at point of no return (crazy face emoji) I have worked my butt off, tears and tantrums to be here. It’s not easy, I still don’t love my body but I am grateful for where I am and the people around me (heart eyes emoji, cheers emoji) (@emmalouiseoldfield)

This finding is supported by extant research by Moulding (Citation2015) which found that women in recovery from eating disorders often speak about this process as ‘personal quests framed around themes of self-discovery, self-care, and agency’ (78). Moreover, a study by Vogel, Rose, and Crane (Citation2018) demonstrated that social media posts with a temporal context (such as transformation photos) that show a more positive past self and more negative current self are less likely to receive social support than posts that display an upward trajectory. In this sense, there are perceptible costs to deviating from representing recovery as a positive journey.

There was a tendency for women weightlifting in recovery from eating disorders to distance themselves from qualities of weakness or pathology. However, during interviews, it became apparent that the desire to present recovery as an upward trajectory occasionally came into conflict with the benefits of speaking about messy, traumatic or unresolved aspects of this experience. In this regard, participants expressed that while recovery was an important part of their life, they wanted to move away from the identity of someone who is ill. As Eve explained:

Talking about it is still the most useful thing I can do about it and sometimes … I feel like I go on about it a bit and I don’t want to be, you know, the ‘eating disorder girl’ (Eve, 20 years old, in recovery from anorexia)

In this sense, women in recovery experience the world in a liminal state of being, caught between two vastly differing embodied experiences and lifestyle practices (Eli Citation2016). Transformation photos reflect this sense of ‘becoming’, projecting movement towards a new identity. Sarah explained why she posts transformation photos on her Instagram account:

For every 9 photos, I have a transformation photo. Whether that’s in terms of my face, in terms of my body, in terms of how, you know, the mental strength or the mental growth. So if someone new comes on my page, they can kind of acknowledge that that’s my journey … I see it less of an embarrassment now and I see it more of an empowerment and I know that I wouldn’t associate anorexia as my identity (Sarah, 18 years old, in recovery from anorexia)

By rejecting identities perceived as weak or pathological, women in recovery develop a subjectivity premised on empowerment and ‘survivorship’. This emerged consistently from the netnography, as one observational field note reads:

‘Survivorship’ is a common way of narrativising weightlifting and eating disorder recovery. Some women write that they are a ‘survivor’ in their Instagram account biographies (e.g. ‘bulimia survivor’) alongside where they are from and what they do for a living. In these instances, survivorship holds more than a descriptive quality; it is an identity. (field note)

In connection to the ‘transformation imperative’ within online health and fitness spaces, Camacho-Miñano and colleagues write, ‘transformation demands not only that individuals work on their bodies but also that they “improve” their psychological attitudes. As such, it requires a makeover of subjectivity itself that could be identified in incitements towards upgraded forms of confident selfhood’ (Citation2019, 653). In this sense, Instagram is a space to develop entrepreneurial modes of selfhood, centred on survivorship, self-actualisation and ‘overcoming’ as well as ‘becoming’.

Discussion

In our findings, we demonstrate that transformation photos hold important meaning for women who are weightlifting in recovery from eating disorders, by providing access to new modes of becoming, acting as ‘mediated memories’, and externalising movement towards new identities. In this final discussion, we examine the socio-cultural moment in which these images have captured the popular imagination. Here we seek to, as Gill and Orgad advocate, ‘treat the narratives, metaphors, images, exhortations, and technologies in these sites as powerful pedagogical resources that teach women how to think of and feel about themselves and their relationships to others, in neoliberal times’ (Citation2018, 481). What, then, is it about this cultural moment that makes transformation photos a desirable expression of selfhood?

The widespread resonance with transformation photos, we argue, aligns with emergent literature on the cultural turn towards survivorship and resilience narratives (Orgad Citation2009; Gill and Orgad Citation2018). Of course, surviving and overcoming immense struggle is of huge personal significance. However, in the context of eating disorder recovery, we are concerned that transformation photos and narratives of survivorship do much to foreground the experiences of the individual over the collective. In this respect, systemic socio-cultural issues that are linked to the development of eating disorders (for example; fatphobia, the thin ideal, violence against women and restrictive gender roles) are re-privatised and made an area of personal responsibility (Fullagar et al. Citation2017). In this regard, through transformation photos, eating disorder recovery is made an individual journey of self-discovery, rather than a highly political and collective struggle which disproportionately impacts women and girls in patriarchal societies (Hesse-Biber et al. Citation2006). In this respect, while it could be argued that by connecting the personal to hashtags (such as #gainingweightiscool) women are forming online ‘therapeutic publics’, it remains problematic that the tools for recovery advocated for are not external support or structural change, but internal goods and self-actualisation.

The emphasis on speaking about personal journeys of recovery is an essential component of this uptake of responsibility. As Orgad explains, ‘the survivor is constituted upon the act of speaking … silence (associated with the victim), on the other hand, is completely rejected as an option. It is not only a sign of weakness, but is also an unvirtuous act’ (Citation2009, 154). Thus, in postfeminist times, hegemonic femininity requires women and girls be vocal about their experiences and their trauma, lest their silence be pathologised (Harris Citation2004). As Dobson contends, ‘the figure of the confident, vocal, “powerful” (and still sexy) girl has become one of the most legible forms of normative and “healthy” young feminine subjectivity … This new femininity requires a high degree of visibility, articulation, and self-confidence’ (Citation2015, 178–9). In this respect, transformation photos are a commonplace method of articulating journeys towards a new kind of subjectivity. In addition to demonstrating a physical transformation, women must speak about their recovery in specific ways in order to be acknowledged as virtuous and credible survivors. They are a way of shunning a pathological identity and becoming an ‘empowered’ feminine subject, in line with hegemonic expectations.

Conclusion

To conclude, it is worthwhile to briefly reflect on the merits of focusing on one specific digital cultural artefact in order to enhance understandings of women’s experiences using weightlifting as a mode of recovery from eating disorders. While these women’s recovery takes place in multiple diverse sites (the gym, at home, in public life) we felt it useful to ground much of the study in the digital, which participants use as a dedicated space to reflect on and narrativise their experiences. The vast and ephemeral nature of social media spaces led us to narrow the focus even further, to look at one specific method of communication that was commonplace across the sample; transformation photos. By combining three rich data sets (interviews, photo-elicitation, netnography), we were able to explore transformation photos at both the subjective and the cultural level. We suggest that future research adopt this kind of multi-sited methodology to explore to other digital artefacts or mimetic practices, as such an approach is effective in ‘meeting participants where they are’. In this sense, rather than using ‘traditional’ methods, to ask populations or group about a particular topic or experience, this research advocates for scholarship which values exploration of how digitally mediated lives are currently being lived.

It is noteworthy to add that, in our experience, qualitative ethics have yet to fully catch up with the kinds of methodological projects we are advocating for. This presented as a challenge at numerous points in the study, leading to thorough group discussions around ethics and research integrity as and when we found ourselves in unchartered territory. Throughout the research, the issue of image sharing, in particular, emerged as an ethical consideration. On the one hand, orthodox social science research is cautious about publicly non-anonymised images of research participants. On the other, this need for visual anonymity did not have the same purchase in our participants’ lives as this orthodoxy would assume. Indeed, sharing non-anonymised images was important for participants both as an additional facet to sharing their recovery narrative and as recognition for their contribution to the ongoing conversation on this topic. To this end, we suggest that (where appropriate) future researchers engage in frank and open dialogues with participants regarding how they would like their words, images, and stories to be represented.

Finally, although as authors we represent a range of voices on the fitness and social media scene, a limitation of this paper is that the knowledge we have developed here is partial and somewhat shaped by our unique positionality. Therefore, more research is needed to bring to bear alternative perspectives on this digital artefact. Most notably, all of the authors are white, heterosexual women as are most of the account holders from whom we collected transformation photos. This dominance of white women in the transformation photos represents both an overrepresentation of whites in social media fitness communities and the prominence of white body types as the ‘ideal’ in these networks. Future research would benefit from exploring the ‘becoming’ of diverse body types and the kinds of narratives that are shaped around this process.

Acknowledgments

We thank the anonymous reviewers for their useful feedback on earlier drafts of this paper. We are also incredibly grateful to the women who participated in this study for sharing their stories with us.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Hester Hockin-Boyers

Hester Hockin-Boyers is a Doctoral Researcher in Sociology at Durham University. Her PhD (funded by the ESRC) explores women’s use of weightlifting as an informal strategy for recovery from eating disorders. Her current research interests cohere around issues of embodiment and the sociology of the body, feminist theory, eating disorders and digital spaces.

Stacey Pope

Dr Stacey Pope is an Associate Professor in the Department of Sport and Exercise Sciences at Durham University. Her research interests are broadly located in the area of gender, sport and inequality and she is especially interested in women’s experiences in traditionally ‘male’ sports. Her research has been published in a range of international journals and she is author of The Feminization of Sports Fandom: A Sociological Study (Routledge, 2017) and co-editor (with Gertrud Pfister) of Female Football Players and Fans: Intruding into a Man’s World (Palgrave Macmillan, 2018).

Kimberly Jamie

Dr Kimberly Jamie is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Sociology at Durham University. Her research interests centre on health, medicine, and sociology of the body. Her work is interdisciplinary and she has published in a range of social science, and practice-focused journals.

References

- Alberga, A. S., S. J. Withnell, and K. M. von Ranson. 2018. “Fitspiration and Thinspiration: A Comparison across Three Social Networking Sites.” Journal of Eating Disorders 6 (1): 39. doi:10.1186/s40337-018-0227-x.

- Bell, M. 2009. ““@ the Doctor’s Office”: Pro-anorexia and the Medical Gaze.” Surveillance & Society 6 (2): 151–162. doi:10.24908/ss.v6i2.3255.

- Bluteau, J. M. 2019. “Legitimising Digital Anthropology through Immersive Cohabitation: Becoming an Observing Participant in a Blended Digital Landscape.” Ethnography 1–19. Advanced online publication.doi:10.1177/1466138119881165.

- Brabazon, T. 2006. “Fitness Is a Feminist Issue.” Australian Feminist Studies 21 (49): 65–83. doi:10.1080/08164640500470651.

- Brace-Govan, J. 2002. “Looking at Bodywork: Women and Three Physical Activities.” Journal of Sport and Social Issues 26 (4): 403–420. doi:10.1177/0193732502238256.

- Brace-Govan, J. 2004. “Weighty Matters: Control of Women’s Access to Physical Strength.” The Sociological Review 52 (4): 503–531. doi:10.1111/j.1467-954X.2004.00493.x.

- Brain, J. 2002. “Unsettling Body Image’ Anorexic Body Narratives and the Materialization of the Body Imaginary’.” Feminist Theory 3 (2): 151–168. doi:10.1177/1464700102003002342.

- Budgeon, S. 2003. “Identity as an Embodied Event.” Body & Society 9 (1): 35–55. doi:10.1177/1357034X030091003.

- Caliandro, A. 2017. “Digital Methods for Ethnography: Analytical Concepts for Ethnographers Exploring Social Media Environments.” Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 47 (5): 551–578.

- Camacho-Miñano, M. J., S. MacIsaac, and E. Rich. 2019. “Postfeminist Biopedagogies of Instagram: Young Women Learning about Bodies, Health and Fitness.” Sport, Education and Society 24 (6): 651–664. doi:10.1080/13573322.2019.1613975.

- Chancellor, S., T. Mitra, and M. De Choudhury 2016. “Recovery amid Pro-Anorexia: Analysis of Recovery in Social Media.” Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, San Jose, USA, 2111–2123.

- Coleman, R. 2008. “The Becoming of Bodies.” Feminist Media Studies 8 (2): 163–179. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680770801980547.

- Deleuze, G., and F. Guattari. 2000. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Dias, K. 2013. “The Ana Sanctuary: Women’s Pro-Anorexia Narratives in Cyberspace.” Journal of International Women’s Studies 4 (2): 31–45.

- Dobson, A. S. 2015. “Girls’ ‘Pain Memes’ on YouTube: The Production of Pain and Femininity in a Digital Network.” In Youth Cultures and Subcultures: Australian Perspectives, edited by S. Baker, B. Robards, and B. Buttigieg, 173–182. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Eikey, E. V., and M. C. Reddy 2017. ““It’s Definitely Been A Journey”: A Qualitative Study on How Women with Eating Disorders Use Weight Loss Apps.” Proceedings of the 2017 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Denver, USA, 642–654.

- Eli, K. 2016. ““The Body Remembers”: Narrating Embodied Reconciliations of Eating Disorder and Recovery.” Anthropology & Medicine 23 (1): 71–85. doi:10.1080/13648470.2015.1135786.

- Fox, N., K. Ward, and A. O’Rourke. 2005. “Pro-anorexia, Weight-loss Drugs and the Internet: An ‘Anti-recovery’ Explanatory Model of Anorexia.” Sociology of Health & Illness 27 (7): 944–971. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9566.2005.00465.x.

- Fullagar, S., E. Rich, J. Francombe-Webb, and A. Maturo. 2017. “Digital Ecologies of Youth Mental Health: Apps, Therapeutic Publics and Pedagogy as Affective Arrangements.” Social Sciences 6 (4): 135. doi:10.3390/socsci6040135.

- Giddens, A. 1991. Modernity and Self-identity: Self and Society in the Late Modern Age. Reprint ed. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Gill, R. 2007. “Postfeminist Media Culture: Elements of a Sensibility.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 10 (2): 147–166. doi:10.1177/1367549407075898.

- Gill, R., K. Henwood, and C. McLean. 2005. “Body Projects and the Regulation of Normative Masculinity.” Body & Society 11 (1): 37–62. doi:10.1177/1357034X05049849.

- Gill, R., and S. Orgad. 2018. “The Amazing Bounce-Backable Woman: Resilience and the Psychological Turn in Neoliberalism.” Sociological Research Online 23 (2): 477–495. doi:10.1177/1360780418769673.

- Goodyear, V. A., K. M. Armour, and H. Wood. 2019. “Young People Learning about Health: The Role of Apps and Wearable Devices.” Learning, Media and Technology 44 (2): 193–210. doi:10.1080/17439884.2019.1539011.

- Goredema-Braid, B. 2010. “Ethical Research with Young People.” Research Ethics 6 (2): 48–52. doi:10.1177/174701611000600204.

- Griffiths, S., and A. Stefanovski. 2019. “Thinspiration and Fitspiration in Everyday Life: An Experience Sampling Study.” Body Image 30: 135–144. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2019.07.002.

- Griffiths, S., D. Castle, M. Cunningham, S. B. Murray, B. Bastian, and F. K. Barlow. 2018. “How Does Exposure to Thinspiration and Fitspiration Relate to Symptom Severity among Individuals with Eating Disorders? Evaluation of a Proposed Model.” Body Image 27: 187–195.

- Haraway, D. 1988. “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective.” Feminist Studies 14 (3): 575–599. doi:10.2307/3178066.

- Harris, A. 2004. Future Girl: Young Women in the Twenty-first Century. New York: Routledge.

- Harrison, B. 2002. “Seeing Health and Illness Worlds – Using Visual Methodologies in a Sociology of Health and Illness: A Methodological Review.” Sociology of Health & Illness 24 (6): 856–872. doi:10.1111/1467-9566.00322.

- Hesse-Biber, S., P. Leavy, C. E. Quinn, and J. Zoino. 2006. “The Mass Marketing of Disordered Eating and Eating Disorders: The Social Psychology of Women, Thinness and Culture.” Women’s Studies International Forum 29 (2): 208–224. doi:10.1016/j.wsif.2006.03.007.

- Heyes, C. J. 2007. “Cosmetic Surgery and the Televisual Makeover.” Feminist Media Studies 7 (1): 17–32. doi:10.1080/14680770601103670.

- Holmes, S. 2017. “‘My Anorexia Story’: Girls Constructing Narratives of Identity on YouTube.” Cultural Studies 31 (1): 1–23. doi:10.1080/09502386.2016.1138978.

- Ibrahim, Y. 2015. “Instagramming Life: Banal Imaging and the Poetics of the Everyday.” Journal of Media Practice 16 (1): 42–54. doi:10.1080/14682753.2015.1015800.

- Jong, S. T., and M. J. N. Drummond. 2016. “Exploring Online Fitness Culture and Young Females.” Leisure Studies 35 (6): 758–770. doi:10.1080/02614367.2016.1182202.

- Kozinets, R. V., P. Y. Dolbec, and A. Earley. 2014. “Netnographic Analysis: Understanding Culture through Social Media Data.” In Sage Handbook of Qualitative Data Analysis, edited by U. Flick, 262–275. Sage: London.

- Kroon Van Diest, A. M., and M. Perez. 2013. “Exploring the Integration of Thin-ideal Internalization and Self-objectification in the Prevention of Eating Disorders.” Body Image 10 (1): 16–25. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2012.10.004.

- LaMarre, A., and C. Rice. 2017. “Hashtag Recovery: #eating Disorder Recovery on Instagram.” Social Sciences 6 (3): 1–15.

- Leggatt‐Cook, C., and K. Chamberlain. 2012. “Blogging for Weight Loss: Personal Accountability, Writing Selves, and the Weight-loss Blogosphere.” Sociology of Health & Illness 34 (7): 963–977. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9566.2011.01435.x.

- Lupton, D. 2016. The Quantified Self: A Sociology of Self-tracking. Cambridge UK: Polity Press.

- McNay, L. 1999. “‘Gender, Habitus and the Field’.” Theory, Culture & Society 16 (1): 95–117.

- Morrow, O., R. Hawkins, and L. Kern. 2015. “Feminist Research in Online Spaces.” Gender, Place & Culture 22 (4): 526–543. doi:10.1080/0966369X.2013.879108.

- Moulding, N. T. 2015. “Gendered Intersubjectivities in Narratives of Recovery from an Eating Disorder.” Affilia 31 (1): 70–83. doi:10.1177/0886109915576519.

- Norman, M. E., and F. J. Moola. 2019. “The Weight of (The) Matter: A New Material Feminist Account of Thin and Fat Oppressions.” Health 23 (5): 497–515. doi:10.1177/1363459317724856.

- Orgad, S. 2009. “The Survivor in Contemporary Culture and Public Discourse: A Genealogy.” The Communication Review 12 (2): 132–161. doi:10.1080/10714420902921168.

- Patching, J., and J. Lawler. 2009. “Understanding Women’s Experiences of Developing an Eating Disorder and Recovering: A Life‐history Approach.” Nursing Inquiry 16 (1): 10–21. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1800.2009.00436.x.

- Prichard, I., A. C. McLachlan, T. Lavis, and M. Tiggemann. 2017. “The Impact of Different Forms of #fitspiration Imagery on Body Image, Mood, and Self-Objectification among Young Women.” Sex Roles 78: 789–798.

- Radley, A., and D. Taylor. 2003. “Images of Recovery: A Photo-Elicitation Study on the Hospital Ward.” Qualitative Health Research 13 (1): 77–99. doi:10.1177/1049732302239412.

- Rich, E., and A. Miah. 2014. “Understanding Digital Health as Public Pedagogy: A Critical Framework.” Societies 4 (2): 296–315. doi:10.3390/soc4020296.

- Riley, S., and A. Evans. 2018. “Lean Light Fit and Tight: Fitblr Blogs and the Postfeminist Transformation Imperative.” In New Sporting Femininities: Embodied Politics in Postfeminist Times, edited by K. Toffoletti, H. Thorpe, and J. Francombe-Webb, 207–229. Switzerland: Palgrave.

- Shilling, C. 1993. The Body and Social Theory. London: SAGE.

- Shinebourne, P., and J. A. Smith. 2009. “Alcohol and the Self: An Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis of the Experience of Addiction and Its Impact on the Sense of Self and Identity.” Addiction Research & Theory 17 (2): 152–167. doi:10.1080/16066350802245650.

- Smith, J. A., P. Flowers, and M. Larkin. 2009. Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis: Theory, Method and Research. London, England: Sage.

- Steinem, G. 1994. Moving Beyond Words. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Tiggemann, M., and M. Zaccardo. 2015. ““Exercise to Be Fit, Not Skinny”: The Effect of Fitspiration Imagery on Women’s Body Image.” Body Image 15: 61–67. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2015.06.003.

- van Doorn, N. 2011. “Digital Spaces, Material Traces: How Matter Comes to Matter in Online Performances of Gender, Sexuality and Embodiment.” Media, Culture & Society 33 (4): 531–547. doi:10.1177/0163443711398692.

- Vogel, E. A., J. P. Rose, and C. Crane. 2018. ““Transformation Tuesday”: Temporal Context and Post Valence Influence the Provision of Social Support on Social Media.” The Journal of Social Psychology 158 (4): 446–459. doi:10.1080/00224545.2017.1385444.

- Warin, M. 2010. Abject Relations: Everyday Worlds of Anorexia. London: Rutgers University Press.