ABSTRACT

This paper considers how sociotechnical imaginaries structure the development and use of sensing technology in the Canadian Arctic. The central claim is that these technological developments are grounded in a particular sociotechnical imaginary centred on risk, vulnerability, and probability, which frames the Arctic as a space threatened by myriad future dangers. Within this sociotechnical imaginary, the Canadian state’s security and sovereignty are threatened by the potential for competing expressions of power enabled by climate change, technological diffusion, and other trends stemming from the international scale. Consequently, sensing is envisioned as a mode of sovereign power to protect Canada’s Arctic territory and manage threats in their indeterminate and potential form.

We believe it self-evident that the world of the not-too-distant tomorrow being forged today in the flames of desperate battles, will be an aerial world […]. The very concept of distance will have altered […].

This world of tomorrow will seize advantage of the fact that in flight an arc and not a straight line is the shortest distance between two points and that the Great Circle, one fourth of it in Canada, is the world’s best travelling route. (Davies Citation1944, 40, my emphasis)

Introduction

Imaginaries of tomorrow often draw from those of the past to structure and interact with technologies of the present within defined spaces. The Canadian Arctic represents such a space as its imagined futures are not altogether divorced from imaginaries of the past and support a particular mode of desired sociotechnical governance by the Canadian state across its Arctic territory. Historically, this mode of sociotechnical governance has focused on the innovation and deployment of technology as a mode of sovereign power towards multiple and overlapping (and at times contradictory) efforts, including economic development, nation-building, and security.

This article focuses on developing and using sensing technology to secure Canada’s Arctic territory. Canada is focused on technological advancement designed to enhance the state’s sensing capacity (the combination of surveillance and intelligence) by expanding that capacity within and beyond its cartographic borders to defend its de facto sovereignty. Time and space are the twin axes of sovereign control for which the state is working to extend its power in more networked, layered, and technologically intensive ways. These efforts mirror Foucault’s theorisation of the Panopticon, which represents an idea or ‘the oldest dream of the oldest sovereign: None of my subjects can escape and none of their actions is unknown to me.The central point of the Panopticon still functions, as it were, as a perfect sovereign’ (Foucault Citation2007, 66). The technology and materiality of the Panopticon and surveillance are generally more than the sum of a pre-ordained need (to discipline and punish). Instead, they are entwined within the production of intersecting and overlapping discourses and other semiotic tools that organise space and bodies while reproducing segments of power.

Following this insight, this paper asks: why has developing and using sensing technology in the Arctic become a key focus of the Canadian government? For the Arctic, thinking about technological development strictly in conventional and instrumental terms does not offer a complete account of how and why sensing technology has become a key focus of development by the Canadian Federal Government within its approach to Arctic security.

This paper demonstrates how sociotechnical imaginaries, constructed through layers of meaning and representation in discourse and other semiotic structures, are entangled with scientific research and technological development. Specifically, this paper considers how sociotechnical imaginaries structure the development and use of sensing technology for security in the Canadian Arctic.The central claim of this paper is that these technological developments are grounded in a particular sociotechnical imaginary centred on risk, possibility, and vulnerability, which frames the Arctic as a space threatened by myriad future dangers. Broadly, this paper demonstrates that the New Arctic functions as a productive sociotechnical imaginary concerning the innovation of security technologies designed to make a spectrum of future threats visible and manageable in the present.

This article makes a novel contribution in three key ways. First, academic and policy attention to Arctic security within Canada and abroad has been reignited in recent years, especially following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, given its effects on Arctic governance efforts in the international sphere. However, this focus has primarily been within a policy-oriented rationalist lens, particularly within the Canadian context. Specifically, recent geostrategic interest in Arctic security has deliberated on the potential for interstate conflict in the region between Russia and western Arctic states (which in some ways is reminiscent of Cold War concerns) while questioning the endurance of Arctic governance structures like the Arctic Council and the region’s inherent stability as an exceptional zone of peace. Second, Critical Security Studies (CSS) has primarily focused on the issues of climate change and human security concerning the Arctic. While there are notable interventions theoretically interrogating Arctic security in policy and discourse (e.g. Salter Citation2019; Sejersen Citation2021), sensing technology has only recently begun to be examined through a more comprehensive and critical lens despite the prevalence of technology and surveillance-focused research in CSS (see Johnson Citation2021). Lastly, while the relationship between sovereignty and security is a well-worn subject within the Canadian Arctic literature, this study contributes a novel approach to analysing how sovereignty is rhetorically and materially invoked through sociotechnical imaginaries of Arctic (in)security.

Empirically, the paper draws from multiple discrete sources to form a cohesive demonstration of the Arctic’s historical and contemporary representation. The paper draws from articles in the Globe and Mail newspaper to demonstrate how the Arctic was portrayed as a frontier space to be tamed by science and technological intervention in the early 20th century while illustrating conceptual lines of similarity between that era, the Cold War, and contemporary Arctic security efforts. While media representations are not a substitute for policy, they offer a window into the contours of earlier Arctic imaginaries. The paper also draws from official Government of Canada policy reports and frameworks, along with public reports in the defence research and industry sphere and advertising by firms involved in the production of sensing technologies, specifically the Canadian firm MDA Inc.

This paper is organised as follows. It begins with a conceptual discussion of sociotechnical imaginaries and draws from the work of Sheila Jasanoff and others to illustrate their usefulness as a lens to examine Arctic security and its link to sovereignty in Canada. While linking and contrasting these earlier imaginaries, the paper highlights the work of Chartier (Citation2018) and his conceptualisation of the imagined North. The paper builds on the imagined North by demonstrating how the region is imagined as a futurized space vulnerable to a complex network of global forces within the New Arctic, which is a term variably used to capture recent significant and likely enduring changes in the Arctic’s natural and political environments. Subsequently, the paper discusses how the New Arctic is premised on a specific ontology of deterritorialisation, relationality, and complexity. This ontology is primarily approached within Arctic security practices through an epistemic framework of risk, vulnerability, and probability, which are relational and directly linked to sensing practices. This section is broken into three sub-sections to discuss how each relationship serves the dominant sociotechnical imaginary underlying the New Arctic and its interaction with sensing technology in the space and marine domains.

Sociotechnical imaginaries

The Arctic’s dominant cultural, social, and political understandings are part of a broader set of discourses and epistemic practices that shape the region as a material space. This paper draws on Jasanoff’s (Citation2015) understanding of sociotechnical imaginaries to analyse the Canadian Arctic and situate Canada’s focus on developing sensing technologies for Arctic situational awareness. Specifically, the paper invokes the notion of a security imaginary. Miller uses the term security imaginary to argue that there has been ‘a significant transformation in the imagination and governance of security since World War II’ (Miller Citation2015, 278). Miller understands the emergence of a global security imaginary situating human welfare and survival in relation to the proliferation of genuinely global (as opposed to international) threats such as pandemics and economic contagion. In my understanding, a security imaginary is a specific type of sociotechnical imaginary that underscores the logic and modes of reasoning deployed towards the production and use of technology in the name of security, which I adopt here.

The security imaginary is a social and material expression of an insecure world and conditions the essential elements, including policy, that partially make up that world. A specific technology’s relationship to the social at the level of materiality is not pre-given, meaning that technology results from a particular technological imperative produced through specific meanings and practices (Davidshofer, Jeandesboz, and Ragazzi Citation2017, 207; Müller Citation2015, 34). Within security considerations, technological development is grounded in specific social, political, economic, cultural, and other normative ideas embedded within frameworks of understanding linked to the state’s interests and ways of being secure in the world.

In a more general sense, following influential accounts of imaginaries by Said (Orientalism), Anderson (the Nation), and others, sociotechnical imaginaries ‘are collectively held, institutionally stabilized, and publicly performed visions of desirable futures, animated by shared understandings of forms of social life and social order attainable through, and supportive of, advances in science and technology’ (Jasanoff Citation2015, 4). The sociotechnical imaginary occupies the intellectual space between cultural production and representation and material iteration through co-production. Co-production indicates the reciprocal and relational nature of sociotechnical imaginaries as existing through the mutually constitutive forces of semiotic representation and material-technological articulation (Jasanoff Citation2015, 3; see Gregory Citation1995; McCarthy Citation2021; Vonderau Citation2017).

The concept of sociotechnical imaginaries is helpful in analysing the Canadian Arctic as a security space in several respects. First, while classic securitisation theory focuses on the discursive construction of security in response to an existential threat, it is traditionally limited in its dealing with ‘[c]onstructions of danger that lie below the threshold of existentialism, such as the concept of risk’ (Methmann and Rother Citation2012, 325) in favour of an event focused view, where securitisation is premised on a binary of before (non-security) and after (security) (Huysmans Citation2011, 377). Further, securitisation may be institutionalised such that ‘[t]he need for drama in establishing securitization falls away because it is implicitly assumed that when we talk of this issue, we are by definition in the area ofurgency’ (Buzan et al. Citation1998, 28). Within the Canadian Arctic, the issue of sovereignty embodies the degree of institutionalization deemed necessary for securitisation. Sovereignty exemplifies a ready-made set of characteristics legitimising specific security practices based on those taken-for-granted qualities, particularly the idea that sovereignty is an inviolable right of all states. Within the contemporary sociotechnical imaginary, the Canadian Arctic is not vulnerable to any one existential threat but rather a multitude of risks. Hence, Canada is concerned with technological solutions to defend Arctic sovereignty through sensing. Here, the state is recognised as a critical political actor in defining and providing security. However, the state is not the only security actor, as literature on security governance demonstrates the role of non-state actors (e.g. Krahmann Citation2005; Lea and Stenson Citation2007). Nonetheless, the state retains an explicit security role, specifically as that which legitimates the normative basis upon which sociotechnical imaginaries are formed and deployed (e.g. through policy) and provides the necessary material resources for those imaginaries to be acted upon and materially realised. In sum, sociotechnical imaginaries provide a robust framework to interrogate and destabilise the technological solutionism that underlines instrumental and rationalist notions of what technology is and can do, especially by the state, in the name of security.

Rarely, if ever, is there one imaginary, as there are typically competing, overlapping, and contradictory imaginaries. There may be a hegemonic imaginary, where notions of security dominate popular understanding and become a focal point for researchers, given that securitisation often requires allusion to affect and social-psychological notions of threat contoured by the future (e.g. Harrington Citation2022; McCarthy Citation2021).

This paper now examines how the Arctic and its future have been imagined and their relationship to security.

Arctic imaginaries: past and present

Local and regional dynamics in the Arctic increasingly embrace a global security imaginary as the ontological root of contemporary threats. The Arctic security imaginary can be understood as a securitised understanding of the world mediated by ‘endemic’ or ‘environmental’ threat (in the sense that threat is omnipresent, spatially and temporally) (Massumi Citation2015, 27) legitimating pre-emptive action ‘premised to a significant degree upon the exercise of the imagination’ (Stockdale Citation2013, 146). The Arctic is often invoked as a site of significant interest given its potential for future transportation routes and generating many of the planet’s remaining extractive resources (though that potential may be overstated). Further, the Arctic invokes a sense of wonder through its natural and atmospheric distinctiveness. Indeed, the Arctic is often portrayed as terra nullius primed for human exploration, which has long been captured in adventure stories and has served as a metaphor to illustrate the struggles of the human condition. Likewise, the Arctic is often presented as a homogenised space divorced from history and the lived experiences of those who call the North home. This reductionist understanding of the Arctic is captured by Daniel Chartier’s concept of the ‘imagined North’. The imagined North

falls into differentiated imaginaries – the ‘North’, Scandinavia, Greenland, the Arctic, the poles, even the winter – that are often presented as an amalgam supported by a simplification of forms – horizontality – and colours – white, pale blue, pink hues –, by the presence of ice, snow, and the complete range of cold, by moral and ethical values – solidarity –, but also, by its connection with a ‘beyond’ where the Arctic begins, at the end of the European ecumene and the beginning of a ‘natural’, unknown, empty, uninhabited, and remote world: the Far North. The entirety of these representations forms a system of signs, what I call here out of convenience ‘the imagined North’. (Chartier Citation2018, 9–10)

For Chartier, the two dominant forces shaping the imagined North are Indigenous colonialism and the Arctic’s administration by governments with capitals in the ‘South, who administrate according to their knowledge (seldom based on experience) and the circumstances of their own needs’ (Chartier Citation2018, 11). While the imagined North is de-historicised and defined through the intersection of ‘emptiness, immensity, and whiteness’ that strips ‘the human experience of the territory’ (Chartier Citation2018, 15), the Arctic, in particular, is also securitized and futurized (in the sense that our dominant conceptualisation of the Arctic is in terms of its expected future) through the fusion of these characteristics with vulnerability, specifically to the proliferation of global forces, including climate change (Dittmer et al. Citation2011). Similar to the Anthropocene imaginary described by Harrington (Citation2022), the New Arctic draws on some of the familiar tropes of bareness and elemental life while simultaneously alluding to the destruction of those qualities through Anthropocene politics, which rest on a cache of spectacularized representations of what climate change means for the future of the Arctic and its representation of a dying world writ large.

Futurizing the Arctic as a social and political imaginary is not entirely new, as colonialist adventure and resource exploitation narratives have fuelled the settler imagination since at least the late 19th and 20th centuries. Security was not the core feature of the imaginary at this time, but science and technology were and continue to be critical narrative vectors of this sociotechnical imaginary. Science and technology are understood to be the tools of conquest and modernisation while deploying epistemic actors (e.g. scientists) as voices of authority who (re)shape sociotechnical imaginaries through that authority.For instance, science was often positioned as a core trait of modernisation and valued in its potential to support northern expansionism for Canada’s nation-building endeavours. The Canadian Arctic and the Indigenous people that inhabit it were often portrayed as inferior and southerners as civilising colonial agents. A Globe and Mail article from 1937 illustrates this portrayal, stating, ‘Eskimos of the Arctic coast have benefited by invasion of the white man’ who ‘taught Eskimos how to trap and have improved the Arctic natives’ standard of living’ (Globe and Mail Citation1937). The Arctic was imagined as an empty space, similar to the way that colonialism imagined the ‘New World’ into existence. The colonial-future imaginary was deployed more bluntly in another Globe and Mail article published in the same year (Citation1937b). As that piece argued,

Millions of the white race some day will find an invigorating home in the Far North, a scientist about to embark on his fourth Arctic research trip predicted today[…] The vast expanse of the Arctic can and will in the future be occupied by millions of white people living in health and comfort.

Likewise, the Arctic was principally framed through this colonial imaginary towards the end of World War II as the source of Canada’s future wealth and expansion as a nation; an Arctic Eldorado that was mischaracterised as a ‘“frozen waste” [and] useless and conquerable’ (Davies Citation1944, 79). As Davies further argued, ‘that the Arctic is difficult to win is granted. But not impossible’ (1944, 79). The reification of science and technology for northward expansion was especially apparent during and the years after World War II as communications and aviation technology improved dramatically and positioned Canada’s Arctic territory at the centre of a future global aviation regime linking Toronto to the world’s other major cities (see Globe and Mail Citation1937, Citation1943a, Citation1943b, 1944). As the Globe and Mail stated in 1944, “[p]lanes flying from Chicago to Moscow would pass over [the] North Magnetic Pole and [the] North Pole, while those bound for Bombay would cross Northern Quebec” (Globe and Mail Citation1944).

Technology as a product of and tool in service of Arctic modernisation and nation-building was routinely mobilised in the media. As with other examples, the Globe and Mail illustrated this tendency in an early commentary on how technology is ‘opening up’ the Arctic:

In 1782 the French fleet entered a desolate region, where fur trading was the only activity. The British sloop steamed into a modern harbor, in which, during the season of navigation, vessels from many countries cast anchor […] This is an amazing change also from the earlier period when Sir John Franklin and his crew of 129 disappeared while searching in Arctic waters for the northwest passage.Radio keeps navigators informed of conditions on Hudson Bay; airships hover above, and the peril of its icy waters is greatly minimized. The Arctic is opening up. Northward also the course of Empire takes its way. (Globe and Mail Citation1937)

The post-war dream of the Arctic’s centrality to a modern global network of metropoles is of the liberal-modernist vein, where aviation and communications technology represented part of what Miller describes as the ‘post-war rise of globalism as a technoscientific ideal’ (Citation2015, 278). Indeed, this technoscientific ideal was likewise deployed as an image of control and mastery over the Arctic’s frontier quality as part of the same nation-building efforts. On this point, Davies argued that ‘Science must be called upon to uncover the secrets of the Arctic. There is no financial profit here for individuals. But there is a challenge to the explorer, the scientist. Canada must stand the expense. The Northwest Passage will only be opened by science’ (1944, 81). The potential for global air travel signalled the Arctic’s transformation from a cultural imaginary infused with symbolic layers of mystery, adventure, and elemental bareness into a sociotechnical imaginary of modernity and a space that could finally be mastered through technological progress, a 20th-century conquest of nature.

The Arctic as a frontier for nation-building continued to excite the post-war imagination, epitomised by Prime Minister John Diefenbaker’s ‘Canada of the North’ speech in 1958 (Harrington and Lecavalier Citation2014, 108), a vision that never materialised. However, the Arctic’s centrality as a potential aviation hub was also a critical threat in the post-war years.The Arctic’s transformation into a geostrategic theatre became more pronounced after 1945, and the Cold War broadly transformed east-west relations such that it provoked additional calls for scientific research and technological development for North American defence (Verrall and Heard Citation2022; Wiseman Citation2015, Citation2022). The strategic reality created by long-range bombers capable of nuclear payloads required early warning capabilities in the Arctic to protect and defend southern targets in Canada and the United States.

This environment resulted in Canada’s joint efforts with the United States to build the Distant Early Warning (DEW) Line, which required new developments in automatic detection (Lajeunesse Citation2007; Naka and Ward Citation2000).Within this new strategic calculus, the Arctic occupied a pre-eminent position within what Matthew Farish (Citation2010) calls the ‘cybernetic continent’. According to Farish, the Arctic was regarded as a frontier zone populated by the intersection of military and scientific interests and actors supporting the ‘production of a cybernetic continent’, which was a ‘task of projects that drew from physics, strategy, and much else, but did so at the specific behest of Cold War imperatives’ (Farish Citation2010, 150). The Arctic was conceived as one strategic centre in a globalised world that served to amplify science and technology as the primary solution to this strategic reality. Notably, these Cold War efforts demonstrate an important line of consistency with contemporary strategic thinking in the Arctic as they rest on particular sociotechnical imaginaries of ‘presumed emptiness’ (Farish Citation2010, 179) that underpin the materialisation of sovereign control through science and technology. Sensing was a critical aspect of this materialisation as technological capabilities evolved on both sides of the Atlantic and was represented by continental defence efforts, including the DEW line, and developments in naval sensing technology supporting undersea surveillance apparatuses to detect submarines (e.g. the Arctic Sound Surveillance System project in the Greenland-Iceland-UK (GIUK) gap and project Spinnaker in Canada) (Dean, Lackenbauer, and Lajeunesse Citation2014, 9; Tamnes and Holtsmark Citation2014, 28; Weir Citation2006).

Following the end of the Cold War and a brief lull in interest by Canada and other states after the 11 September 2001, terrorist attacks, the Canadian federal government signalled its continued interest in Arctic defence research in the early to mid-2000s. This phase began as Conservative Prime Minister Stephen Harper routinely spoke of the Arctic as a core frontier of Canada’s national boundaries (Dodds Citation2011). Within the political zeitgeist of this time, the Arctic was (and at times continues to be) routinely framed as a space ripe for capitalist exploitation and interstate conflict over resources and transport routes in the near-to-distant future. Such discourses have likened recent geopolitical interest in the Arctic to the late 19th century’s surge of colonial expansion in Africa as European imperialism reached a crescendo (Borgerson Citation2008; Huggan Citation2015; Steinberg and Dodds Citation2015). While such comparisons have been challenged as analytically ill-conceived for several reasons (see Claes and Moe Citation2014), there are certain regional similarities in that both Africa and the Arctic are represented through sets of overlapping and often competing imaginaries that are historically contoured as othered spaces.

Importantly, in this era, the issue of ‘situational awareness’ found a more emphatic connection to Arctic security and governance. There is also a clear continuity between the Harper era and current Arctic surveillance initiatives being pursued by the Trudeau Liberals, for instance, through the recent All Domain Situational Awareness (ADSA) programme (National Defence Citation2017a; National Defence Citation2018), particularly as technological innovation relates to intelligence products that contribute towards the visualisation and rationalisation of Canada’s Arctic territory. Sensing practices are designed to illuminate the Arctic using a range of spectrum and sub-spectrum imaging techniques, which are also productive in delineating the state’s territorial boundaries through these products.

Within the logic of the Arctic security imaginary, visualising the boundaries and dynamic activities (including environmental patterns) is critical to achieving all-domain awareness and defending against a spectrum of future threats. Within a security lens, this futurized imaginary is defined by overlapping discourses and semiotic layers that produce the Arctic as a space requiring securitised forms of intervention and ‘structure the conditions of possibility for the management of future uncertain events, and the limits of potential intervention in the alleviation of future threats and dangers’ (Salter Citation2019, 4–5). The Arctic’s natural, unknown, and empty qualities as the imagined North lend themselves to a securitised understanding of space by which the Canadian state must respond, given that its de facto sovereignty is threatened (i.e. the state’s material control of the Arctic). Security practices represent one form of that response. They are performances of sovereignty similar to that described by Wood-Donnelly, who argues that states are materialised as political actors ‘through the repetition of rules, or norms, that the community of states recognizes as legitimate behaviour. To do this, they borrow from a toolkit of recognized symbols ranging from the spectacular to the mundane’ (such as postage stamps) (Wood-Donnelly Citation2019, 13). Drawing on the symbols that underpin the imagined North constitutes one (although not total) avenue of understanding the Arctic and shapes the dominant forms of governance (including security practices), which are likewise representative of the state’s symbolic and material authority across its territory.

The sociotechnical imaginary is, therefore, more than imaginative in a figurative sense; it is a knowledge matrix that forms a system of meaning that contours the parameters of sovereign control and intervention (Latham and Williams Citation2013, 13, 27). Thus, while multiple semiotic systems of representation mobilise a core set of symbols towards different imaginaries, not all imaginaries are equal. Because these representations are invested with and through relations of power, imaginaries embody that power. Within a securitised sociotechnical imaginary, threats are constructed and mobilised through core thematic drivers of representation and understanding, where space is rendered in terms of vulnerability. In turn, the future is made insecure through specific systems of meaning that directly condition the logic of sovereign intervention.

Securing the New Arctic

There are similarities but important differences between the Arctic imaginaries of the past and those shaping current political interventions. The Arctic of the past was an emptied space primed for colonial expansion and nation-building, at least in spirit. The future was presented as inevitable because the Arctic would become a modernised space of northern development and a hub of the world economy and strategic thinking. These visions continue to populate the Arctic imaginary, which sometimes echoes 19th and 20th-century thinking. However, whereas futures of the past were oriented towards a future of certainty, futures of the present are far more uncertain in their proclivity. In the contemporary context, the Arctic’s future is sure to be of growing importance, but the velocity and complexity of contemporary developments throw that future into disarray. The Arctic imaginary of the past was premised on an ontology of certainty, such that science and technology would serve to dominate the Arctic as an empty and wild frontier. However, the contemporary Arctic frontier has shifted and is lost in an ontology of uncertainty. Science and technology continue their trajectory as core aspects of state building and control in the Arctic, but that control is increasingly abstracted spatially, temporally, and materially inside and outside the Arctic.

Apart from traditional security concerns involving military build-up and defence systems, other issues relevant to Arctic security (and policy overall) are branded by the interaction of environmental and human protection and considerations for resource and infrastructural development (Cameron Citation2012; Lackenbauer and Lajeunesse Citation2014), including trade routes. Within this lens, climate change occupies a paradoxical position as potentially disabling and enabling the state and human beings. As a region, the ‘post-Arctic world’ is conceptualised as a site of opportunity where the North emerges as a new centre of the globe, becoming ‘a literal ‘media-terranean’ or draws on an apocalyptic imaginary (Harrington Citation2022; Methmann and Rother Citation2012) portraying the Arctic as‘ an unfolding tragedy; an ominous “end of the Arctic”’ (Zellen Citation2013, 342–343).

The Arctic’s ‘splendid isolation’ (Lajeunesse Citation2016, 34) is currently threatened by anthropogenic industrial activity, producing a gamut of cascading effects centred on rising global average temperatures (NOAA Citation2022). From the perspective of climate science, anthropogenic climate change represents the potential for a radical climatic transformation in the Arctic and the rest of the world. Indeed, this change is characterised by the significant difference between the Arctic’s pre-industrial form and what it will resemble in the future as predicted by current climatic trends, eventually culminating in what some have called the New Arctic. Dr. Christopher Fairall defines the new Arctic as ‘a term used to capture the view that large changes observed in the Arctic climate system in recent decades are both dramatic and unlikely to reverse in the foreseeable future’ (Year of Polar Prediction, Citationn.d.). In contrast, Sejersen (Citation2021) defines the New Arctic from a critical governance perspective and considers the evolving relationships between actors interacting through various mechanisms and political structures at multiple scales. The Arctic’s current governance arrangement constitutes a ‘landscape of risk and opportunity, and these various partnerships, governments, and multi-level cooperative projects together comprise the “New Arctic”’ (Sejersen Citation2021, 237–238). From a security-based perspective, I argue that the New Arctic serves as a sociotechnical imaginary that represents a series of ongoing physical and political transformations that are understood to create a series of emerging threats in the near-to-distant future.

Notably, while Canada recognises climate change as an issue, the sociotechnical imaginary driving Arctic security policy does not draw on apocalypse as a future imaginary to the extent other representations have, as that would undermine the conservative nature of the government’s Arctic policy because it would necessitate much starker action and investment to halt and address climate change. Instead, much of what can be seen in Canada’s Arctic policy, similar to much of the climate change discourse and policy efforts, echoes a politics of adaptation that centres on mitigating vulnerability through resilience (Greaves Citation2016; Methmann and Rother Citation2012). For instance, the Arctic and Northern Policy Framework (ANPF) (Government of Canada Citation2019a) represents Canada’s governance-oriented approach to defence and security that is often rhetorically practiced by the Trudeau Liberals, in which the concepts of building ‘resilient’ communities, ‘robust’ economies, and a ‘sustainable’ environment in the face of future challenges factor heavily into the overarching narrative of cooperation with local, regional, and international partners of the state. These narratives and partnerships facilitate investment into technologies geared towards non-military security issues like search and rescue (SAR) operations, including sensing technology.

In contrast, Canada’s defence policy, Strong, Secure, Engaged (SSE) (National Defence Citation2017b),and Defence Research and Development Canada’s (DRDC) science and technology (S&T) strategy emphasise the need to enhance the state’s adaptive capabilities to the global security environment while also building on the theme of resilience. DRDC, in particular, focuses on technological innovation’s role in preparing Canada for an uncertain future and highlights the Arctic and Canada’s northern approaches as core operating environments requiring special attention (National Defence Citation2014, 13, 16).

The ANPF, DND and DRDC share a foundational understanding of the Arctic’s ontological status but accentuate different aspects of the state’s strategic outlook regarding Canada’s interests. While the ANPF focuses on the Arctic’s recent character as a ‘zone of peace’ and multilateral cooperation, it warns of the risks posed by ‘growing international interest and competition in the Canadian Arctic from state and non-state actors who seek to share in the region’s rich natural resources and strategic position’ (Government of Canada Citation2019b). Likewise, SSE warns that ‘Climate change, combined with advancements in technology, is leading to an increasingly accessible Arctic’ (National Defence Citation2017b, 51).

From a security perspective, climate change is presented as a threat multiplier in a quantitative sense as it increases the scale of potentialities for the Arctic’s exploitation against Canada’s interests and sovereignty. Building on the New Arctic’s ontological foundation as a sociotechnical imaginary, maritime surveillance of these actors and the expected increase in Arctic traffic is of particular concern for Canada. From a defence standpoint, one of the critical challenges currently facing the successful monitoring of this traffic is the lack of diversity in the number and types of sensors in the region. The automatic identification system (AIS) for monitoring marine vessels, coupled with radar and satellite linkage (Satlink), can monitor vessels that conform to broadcasting an AIS signature. However, there are several gaps in current surveillance capabilities. Within this framework, ‘dark targets’ constitute the most urgent threat to the DND and CAF in the region because they ‘are not picked up on sensors or cannot be identified’ (Lackenbauer and Kikkert Citation2018, 25).

Consequently, defence specialists and practitioners argue that there is a clear need to develop new technologies and methods to locate and identify these objects, including combining sensor platforms through a system of systems approach into a ‘multi-sensor maritime domain awareness picture’ (Lackenbauer and Kikkert Citation2018, 25). The threats associated with ‘unknown unknowns’ invoke a methodological need for mapping behaviours in terms of an actor’s ‘patterns of life’ when individual events are disparate, unremarkable, and difficult to link with one another. This behaviour exists below the threshold of threat activity that may be otherwise treated as discrete and unimportant. However, this series of behaviours may demonstrate an explicit security threat when analysed holistically. An example presented in the proceedings of a defence roundtable on implementing Canada’s Arctic priorities under SSE illustrates this securitised logic: ‘a small fishing vessel could be carrying a cruise missile or bringing in illegal foreign fighters’ (Lackenbauer and Kikkert Citation2018, 25). The potential infiltration of overt security threats via these dark targets represents a Trojan Horse analogue made more dangerous through its decentralisation into networked sub-components, which can infiltrate the state’s sovereign space at different nodal points. Individual events may appear unexceptional when viewed independently but become more concerning from a risk-based perspective when examined holistically and relationally.

Strategically, extending border practices is crucial to achieving Canada’s Arctic goals identified within S.S.E. Lackenbauer and Kikkert state that Canada needs to be ‘pushing the borders outward’ and that ‘[d]efence, safety, and security requirements dictate that Canada and its allies must detect, track, and identify vessels when they leave a foreign port and operate in Canada’s [extended economic zone], not just when they enter into Canada’s territorial sea (12 nautical miles from the cost or our straight baselines)’ (Citation2018, 21, 24). The notion of pushing borders outward highlights the dual process of rationalisation by the state towards sovereign control over its northern boundaries. DRDC emphasises a similar theme and the role of technological development in their S&T strategy, which states that ‘the CAF also require additional time and space to react to threats, for example by extending sensor coverage as far away as possible from our forces and leveraging automation and stand-off capacity of CAF weapon systems’ (National Defence Citation2014, 15, my emphasis).In particular, ‘as globalization erased traditional concepts of time and space, making borders porous and encouraging continental integration, national sovereignty was reshaped and the power of national governments to control events reduced’ (Dean, Lackenbauer, and Lajeunesse Citation2014, 24 my emphasis). The growing porousness of borders renders states vulnerable to many emerging threats that are increasingly international, if not global, in their orientation.

Pushing sovereignty outward, therefore, embodies both spatial and temporal characteristics via technologically mediated practices of surveillance and intelligence, which are combined to form techniques of sensing. Sensing is a crucial state-led technique of sovereign power for providing situational awareness (SA) that ‘provides the Government with the ability to perceive the physical (maritime, land, air, and space) and non-physical (cyber and human) domains’ while ‘allow[ing] for the fusion, evaluation, and dissemination of that information’ to create ‘intelligence’ (Government of Canada Citation2010, 30). In brief, sensing is acutely biopolitical in categorising, filtering, and reassembling surveillance data from multiple sensors and deploying that reorganised data as intelligence for state action. Thus, technology-enabled sensing is envisioned as a core feature of expanding and consolidating the state’s sovereign power in the Arctic.

Projecting security through a risk framework socially creates the potential for a much more comprehensive range and volume of threats in the form of potentialities (Amoore Citation2013; Coker Citation2009).While Beck famously defines the risk society as one that is socially ‘preoccupied [with] the future’ (Beck Citation1992, 21), the increasing salience of risk as a framing mechanism for security practices is a more recent thematic turn and signals the influence of actuarial management and insurance schematics on security (Lobo-Guerrero Citation2011). These frameworks are specifically concerned with the unknown unknowns of the more distant future, especially as the Arctic’s melting ice may lead to challenges for Canada’s sovereignty and de facto control over its territorial borders and adjacent waters (Grant Citation2016, 30; Lackenbauer Citation2011, 80).

Arctic security in the modern era is bound with futurity because threats that undermine the state’s sovereignty are considered potentialities rather than clear and present dangers. While the term ‘threat’ already implies what may happen rather than what will, the nature of those threats as potentialities is spatially and temporally expanded. The risks associated with threats increase as threats are projected farther into the future, especially concerning state sovereignty, which offers a sense of immediacy to the Arctic’s security in the present. For instance, former Prime Minister Stephen Harper drew explicitly from this Arctic imaginary by insisting that, in an often-cited passage, Canadians in the 22nd – century demand action in the 21st and that Canada was at risk of ‘losing’ the Arctic if it did not ‘use’ it (Dodds Citation2012, 994).

There is a consistent thread that permeates the various Arctic imaginaries over time, from efforts towards colonial expansion that rested on the themes of adventure, mystery, and taming the Arctic’s wildness as a frontier space through the mastery of marine navigation to the equally colonised imaginaries of northward expansion in service of Canada’s nation-building efforts and the defence of sovereignty throughout the Cold War and now.In all cases, the axes of sovereign control have rested principally on notions of scientific progress and technological innovation. Science and technology are critical vectors of modernisation as an idealised practice, which have consistently underpinned political efforts by the state to rationalise and control the Arctic.Thus, the goal of rationalising the Arctic’s spatial and temporal vectors is not new. However, the specific characteristic of networked complexity and the intensity of the spatial and temporal components (i.e. the degree to which time and space are collapsed as impediments to accessing and controlling the Arctic) underlying the New Arctic implies a novelty in how the Arctic is understood concerning this complexity and how it should be secured.

The following section examines the core relationships underpinning the sociotechnical imaginary of the New Arctic formed between risk, vulnerability, and possibility.

Risk, vulnerability, possibility

Risk, vulnerability, and possibility represent the core points of triangulation underpinning the New Arctic and act as the epistemic response to the ontology of threat and complexity. Relationality is an essential feature as each of these imaginaries is given form and substance relative to each other.

The first relationship between risk and vulnerability represents the space where political, economic, cultural and other forces shape vulnerability in relation to threat perception as a social production and the type and degree of insecurity those threats create. The second relationship between risk and possibility represents the empirical rationalisation of threats as numeric probabilities. Lastly, the relationship between vulnerability and possibility represents the space where political action is given material form and where vulnerability directly shapes the conditions of possibility through sociotechnical materials like security technologies. The following section discusses each relationship in detail, supported by examples of policies, programmes, and technologies.

Risk and vulnerability

Framing the Arctic as a vulnerable site threatened by actors in the future has become a central focus for the DND and CAF in combination with other defence analysts. For example, analysts have considered Arctic security through the Canada-US (CANUS) Security Threat Matrix. This framework was developed out of a CANUS conference in 2017 led by the Centre for Resilient Communities at the University of Idaho, the National Maritime Integration Office, and DND/CAF personnel (Bielby Citation2019, 5:13; see Alessa et al. Citation2017, Citation2018).

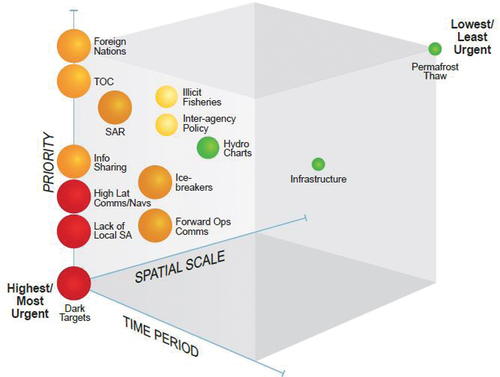

Within the CANUS matrix, threats exist on a continuum of danger in which the riskiest of threats are those ‘unknown unknowns’ that have yet to be conceived or anticipated in any coherent way and which defined the post-9/11 collective imagination. The relationship between risk and vulnerability underscores the social construction of threat and the risks posed to the state. For instance, the CANUS Matrix is notable for where it positions infrastructure and permafrost thaw relative to dark targets, which occupies the most urgent threat category. The emphasis on dark targets and other military-oriented issues is not surprising, given the focus of the Department of National Defence. However, this prioritisation and the CANUS matrix speak to how threats are mobilised and circulated in the world via the positionality of specific actors like defence personnel, white papers, and conferences, which are sites of performance and repetition, as well as how these threats become ordered as politically significant.

Conceptualizing threats and combatting them in this way lends itself to a pre-emptive security strategy. Pre-emptive security aims to capture disparate data points across time and space to anticipate offensive movements increasingly farther into the future. Notably, there are subtle differences between mobilising anticipatory practices towards prevention and pre-emption. As Massumi explains, prevention ‘assumes an ability to assess threats empirically and identify their causes’ whereas pre-emption is an epistemology ‘of uncertainty’ in which ‘threat is still indeterminately in potential’ (Citation2015, 5, 9 original emphasis). Accordingly, there is an important distinction between the two, especially in their verb forms. Whereas prevention as an activity aims to stop something from occurring, pre-emption is an activity that is about controlling and appropriating that something before other actors do. This distinction has significant implications for the practice of state power and security as an expression of sovereignty. For Massumi, while prevention and pre-emption are related because they both ‘[operate] in the present on a future threat’ (Citation2015, 9), they differ ontologically. Preventative thinking is ontologically rooted in ‘an objectively knowable world in which uncertainty is a function of a lack of information, and in which events run a predictable, linear course from cause to effect’ (Citation2015, 5). In contrast, the ontology of pre-emption indicates that threats ‘cannot be specified’ as a consequence of their occurrence within a limitless pre-existence (Massumi Citation2015, 9).

In an objectively knowable world, where threats are understood through linear cause-and-effect relationships within a bounded system, perfect information is theoretically achievable, and therefore, prevention is possible because it is reductionist and mechanistic. In contrast, the New Arctic imaginary is characteristic of a world within an unbounded system (spatially and temporally) of relationality that cannot be reduced to individual components because these relationships have an underlying affective quality, indicating that they are always in flux, including their potential. Prevention becomes difficult, if not impossible, because prevention’s practical application depends on objective knowledge that can only be obtained through complete information, which is impossible in the context of a distant future populated by endless variables. Consequently, this information can only be obtained once a threat has revealed itself in full force as a present-time object or event, at which point it is too late. The consequence of this inability to prevent threats from emergence is a reliance on sensing techniques to halt their emergence into a fully formed threat pre-emptively or to mitigate threat effects by controlling the environment. Theoretically, the state seeks to (re)assert its de facto sovereignty by monopolising situational awareness through sensing – to know everything that can be known and to make empirical predictions about what cannot, i.e. the future.

The relationship between risk and possibility informs these empirical predictions, which the next section discusses.

Risk and possibility

The relationship between risk and possibility involves the empirical prediction of the likelihood that an event will happen. The CANUS Threat Matrix is related to the CANUS Combined Threat Assessment 2011–2031 framework, which is intended to ‘[highlight] for decision-makers the CANSUS […] security environment that may emerge during the next 20 years’ (Government of Canada Citation2017; see and ).

Figure 1. CANUS security threats matrix – Arctic (Alessa et al. Citation2018).

Figure 2. Threat probability scale (Government of Canada Citation2017).

Rationalizing what is possible requires extensive data and the analytical capacity to make sense of that data. Hence, Canada’s focus on Arctic security is on expanding the sensor repertoire and data sources to gain a more complete situational awareness and make better empirical predictions about what is possible, which requires a whole-of-government approach. Many sensing efforts in the Arctic focus on environmental monitoring as the region’s unique conditions pose numerous challenges to domain awareness. The use of scientific practices by the state to expand its knowledge of and claims to territory continues to be used, including for military purposes that may be hindered by the Arctic’s unique environmental and atmospheric conditions (Johnson Citation2021, 413).

The Department of National Defence’s (DND) interest in environmental sensor data indicates one component of Canada’s Arctic surveillance and intelligence strategy. This strategy directly engages with civilian actors in both commercial and public institutions to partially source the development of new technologies and leverage civilian data networks, thereby supporting the production of an all-domain image of the Arctic composed of layered sensor data. Accordingly, the private sector is a ‘key partner’, along with other government departments (OGDs) and academic institutions, for developing ‘[s]urveillance solutions’. According to the Canadian Federal Government, these surveillance solutions ‘will support the Government of Canada’s ability to exercise sovereignty in the North and will provide a greater whole-of-government awareness of safety and security issues, transportation and commercial activity in Canada’s Arctic’ (Defence Research and Development Canada Citation2017, 2). While DND plays a prominent role in researching and procuring new defence technologies, other federal departments, such as the Natural Science and Engineering Research Council (NSERC), are essential actors in delivering research grants that aim to

capitalize on the complementary research and development capacity existing in the universities and in DND in order to generate new knowledge and support the development and application of dual-use technologies in selected areas of interest to both DND and NSERC; build strong two-and three-way linkages and create synergy between researchers in DND and universities and the private sector; achieve the efficient and effective transfer of research results and technology to identified receptors in the public and the private sector (Defence Research and Development Canada Citationn.d.).

The marketised vocabulary of ‘synergy’, ‘efficiency’, and technological ‘transfer points’ underpin the growing salience of ‘dual-use’ technologies as a logic of development. Developing new dual-use technologies (generally meaning technologies with civilian and military uses) and repurposing existing technologies for defence use are concurrent goals. Under the ADSA programme, Canada, through Defence Research and Development Canada (DRDC),

seeks to leverage the development of its technologies, whether developed in-house or via procurement processes, and enable technology transfer through licensing and other mechanisms. Such technology transfer activity aims to enhance Canada’s Security and Defence industry, enabling economic development and ensuring Canadian industrial capabilities to meet the supply chain requirements of the CAF. (Defence Research and Development Canada Citation2017, 4)

Integrating private and public research institutions through procurement into the ADSA programme and developing novel security technologies underscores Canada’s Arctic security strategy and its relationship to sovereignty. This strategy employs specific techniques of state power premised on extending state authority outward spatially and temporally through webs of actors and technologies. Overall, the systems of systems sensing network envisioned in the Arctic has the twin goals of monitoring and predicting the patterns of life of various actors, particularly in the marine domain, to allocate state resources efficiently. Assembling disparate sensors and data sets into a networked system of imaging and intelligence production resembles the just-in-time methods of post-Fordist production chains that enable the mapping of production against demand indicators, coalescing into a final commodity unit that is comparatively cost-effective, efficient, and adaptable to change relative to a centralised production structure. The surveillance supply chain is produced through a decentralised network of suppliers and other actors while producing a near real-time image of the Arctic and its dynamic conditions. For example, sensing practices relay the sovereign eye through a human-machine interface on several stations, including ships within and outside the Arctic space. This interface is represented by Lockheed Martin’s work on building ‘command and surveillance system integrator capability’ through its Combat Management System 330 (CMS 330) onboard the new Irving-built Arctic and Offshore Patrol Ships (AOPS) (Lockeed Martin Canada Citation2024).

The CMS includes a Human-Machine Interface, Sensor adaptation, and Information System Access to the Defence Wide Area Network and Consolidated Secret Network Infrastructure, enabling data collection, storage, processing, and situational awareness through data fusion regimes relayed through command stations. Under these conditions, surveillance nodal points are collated and layered differently over different points in time and space. This ability supports the consolidation of state power through its control of these practices and the assembled surveillance product supporting intelligence production, thereby producing the Arctic as secure and sovereign.

The state’s reliance on sensing as a mode of sovereign pre-emption resembles David Chandler’s argument concerning the Anthropocene, where ‘Anthropocene ontopolitics seeks to govern in the face of the loss of modernist epistemological assumptions: governing thereby seeks to adapt or respond to the world rather than seeking to control or direct it’ (Chandler Citation2018, 21). According to Chandler, modernisation is no longer concerned with increasing our control over the world (as was the mastery of nature with industrial power). Instead, modernisation is now about increasing our knowledge of the world to adapt to the conditions of the Anthropocene itself. The transition to sensing as a mode of governance is the preferred method of adaptation and, according to Chandler, represents a transition from strategies of Mapping because the ontology of sensing is flatter, meaning that it is not concerned with causation so much as it is concerned with correlation. Sensing as a practice is related to the rise of the ‘resilience’ discourses in that ‘Sensing accepts that little can be done to prevent problems’and ‘seeks to work on how relational understandings can help in the present’ (Chandler Citation2018, 88–89), including in terms of eliciting a governance strategy of security against the future. The loss of control over our world and the struggle to reassert the state’s dominance is why sensing practices are intimately bound up with contemporary understandings of security. Increasingly sophisticated sensing technologies are necessary to capture large data sets, rationalise them into comprehensible notions of the world, and understand what they may say about our current vulnerabilities to future conditions. Accounting for possible futures is where the role of imagination comes into play – not as an unrestricted foray outside of an objective world, but one in which that world is uncoupled from both spatial and temporal linearity and reassembled into sets of potentialities. The empirical data points gleaned from the world act as limiters to those potentialities in terms of their probabilities (what is likely to happen, rendered as a rationalised numeric figure) but do not limit possibility in an absolute sense as a potentiality that cannot happen (Atran Citation2006; Hoover Citation2013). Hence, providing situational awareness is a critical strategic concern of defence practitioners because the number of variables in play, including the number of actors, Canada’s extensive geography, and the Arctic’s natural environment, ‘makes it difficult to anticipate what events are going to happen – and, equally important, when’ (Lackenbauer and Huebert Citation2014, 329, emphasis in original). Conceptually, the core aim is to eliminate the potential for unknown unknowns, which requires an endless flow of data to rationalise the past, present, and future.

Eliminating the unknown is impossible, especially as the spatial-temporal horizon is extended outward. Hence, the following section examines technological efforts to approach the unreachable spatial-temporal horizon of total awareness.

Vulnerability and possibility

There is an inherent issue between the goal of rationalising threats as an empirical prediction within unbounded systems that prioritise threat perception of the unknown, such as dark targets. This issue stems from the epistemological contradiction resulting from any attempt to rationalise the unknown, especially the ‘unknown unknowns’, which ontologically rest on the indeterminacy of their potential. Therefore, the only concrete way to counter the unknown is through more data and more awareness to make predictions and squeeze the spatial and temporal spaces that such unknowns may exploit. Within this framework, data accumulation for awareness is a never-ending and insatiable goal because vulnerability against the unknown cannot be cured in an absolute sense.

The relationship between vulnerability and possibility provides the space for political action and where sociotechnical materials take greater form as they are developed and deployed to mitigate vulnerability. Multiple large-scale Arctic technology programmes and projects related to sensing are being used or under development within Canada. The role of technologically mediated sensing practices within a governance strategy of pre-emption to address vulnerability can be illustrated by focusing on two interrelated policy and technological development areas: space-based surveillance and maritime intelligence.

Space is a critical domain as surveillance and communications satellites have become essential state assets (Sloan Citation2021). While supporting a wide range of functions (including environmental monitoring), satellites also monitor human-made infrastructure and activities in the Arctic, such as fishing and ports of entry. For instance, the RADARSAT series of satellites was produced through government, academic and industry partnerships. The original RADARSAT was envisioned as an environmental surveillance satellite for the Arctic rather than strictly military (Surtees Citation1987). The most recent and current RADARSAT satellite, Constellation Mission (RCM), can capture global imagery, day or night, in all weather conditions and rapidly generate image-based products (Government of Canada Citation2021). Monitoring ecological phenomena, such as ice-sheet flows, has critical uses given the navigational requirements of marine travel. The most direct security-related function of RCM is the active sensing of the Arctic’s marine traffic. DND defines active sensing as ‘a capability which can detect non-cooperative or non-emitting vessels’ and is different from passive sensing insofar as it is designed to detect vessels which do not broadcast an AIS signature and who may be attempting to ‘evade detection for illicit purposes’ (Horn Citation2018, 3).

Enhancing surveillance capacity is only one aspect of sensing as a practice for building a complete situational awareness picture in the Arctic. The ability to represent Canada’s geography visually and dynamicallysupports decision-making through intelligence analysis. Consequently, sensing involves the assemblage of visualisation with other data that enables the production of dynamic situational awareness in relation to a given territory like the Arctic. Pattern of life modelling analyzes an actor’s behaviour, combines it with identifying characteristics such as a ship’s AIS, or lack thereof, and collates this data using artificial intelligence. Ideally, this awareness can predict an actor’s future behaviour and decide whether that behaviour is threatening.

Canada’s ultimate goal through Arctic-based technological research is to develop ‘tools and advice for improved effectiveness and greater situational awareness through integrated intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) capabilities, including networked sensors with a shared operational picture’ (National Defence Citation2019, 7). Within maritime security, this means, according to Horn, that ‘it is not sufficient to just develop and employ additional sensing capabilities. Future maritime Command and Control (C2) systems will have to support the processing and exploitation of greater quantities, varieties, and more complex information’ (Horn Citation2018, 4). Information exploitation will include the integration of a greater range and quantity of official ship-based information, including the Long-Range Identification Tracking (LRIT) and AIS data, which is automatically detected, integrated and disseminated by satellite and land-based transponders operated by the Canadian Coast Guard (Government of Canada Citation2019b). The LRIT and AIS were designed by the International Maritime Organization (IMO) and are governed by the IMO’s International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea. Ship identification markers are being combined with global positioning data housed by the Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) within the Global Position Warehouse (GPW), ‘a database which archives ship position reports which were processed by the Navy command and control system’ (Horn Citation2018, 5). These data points are then further assembled with other data sets from multiple sensing platforms in creative and complex ways to understand the patterns of life displayed by ship behaviour. Patterns of life analysis, for example, can be used to predict ship transportation routes and anticipate ship locations using automated machine learning algorithms that include historical fishing, geography, transportation, and other data sets (Horn Citation2018, 8–10).

RADARSAT developer MDL, Inc. provides a more concrete example as it is responsible for an artificial intelligence tool used for marine awareness and developed for the Arctic Maritime Awareness for Safety and Security (AMASS) programme. This tool, named BlueHawk, is a threat-intelligence product that uses surveillance data of the maritime domain from multiple land, sea, and space-based sensors to create an intelligence picture that identifies threatening objects, ranging from ships to environmental disasters (Buffet et al. Citation2017, 19, 29).

BlueHawk is explicitly marketed towards ‘sovereignty protection’, with MDA stating that

BlueHawk™ detects naval vessels encroaching on or transiting Exclusive Economic Zones, territorial waters, or controlled areas. Satellite radar detects dark targets (vessels operating with all electronics and self-reporting turned off), which may be indicative of illegal activities or threats. Operating far beyond the range of patrol aircraft, M.D.A. BlueHawk™ can detect dark targets globally. (MDA Citation2020, my emphasis

BlueHawk and other techno-mediated efforts focused on protecting Canada’s Arctic territory embody much of the same imagery MacTaggart spoke of in Citation1937 when he claimed that ‘Here, at the threshold of the land of the midnight sun, time and distance no longer exist’.

Dark targets are the conceptual embodiment of threats within an unbounded system stripped of spatial and temporal limitations, as they can emerge anywhere and anytime. Within the AMASS programme, MDA has been developing an interface designed to augment BlueHawk that allows for the automated ‘scraping’ of publicly available data, which can be interlaced with BlueHawk data created from the MDA-developed RADARSAT Constellation Mission satellites. MDA’s algorithmic scraper is named ‘Kiliutaq’ (ᑭᓕᐅᑕᖅ), a traditional Inuit name meaning ‘woman’s instrument in the form of a bowl for scraping and softening skins and removing dirt from clothes; scraper; grater’ (Nunavimmiut Collections Institute Citationn.d. my emphasis). Rather than a traditional tool, Kiliutaq is a digital scraper that enables the creation of data cards for individual ships that can be augmented using scraped data from the internet and linking that data to geographic positions using open-source resources, like the GeoNames database (Buffet et al. Citation2017, 15).

Likewise, DND’s Polar Epsilon uses RADARSAT-2 data (which MDA still owns in contrast to the Government of Canada-owned RCM) and operates with two ground stations on the east and west coasts of Canada. According to MDA, Polar Epsilon ‘highlights the near-instant capabilities of the RADARSAT-2 operation. When data is collected by MDA’s satellite on illegal dark vessels or areas of interest around the world for military commanders, it’s transmitted to these stations for processing and analysis’ (MDA Citation2023). The combination of space-based surveillance and marine intelligence technologies exemplifies how security, as an expression of sovereign power, is assembled digitally and materially via diffuse systems. Further, this combination demonstrates how state power is dilated outward by drawing from the global assemblage of data information that, according to the MDA product description for BlueHawk, allows states to ‘[detect] maritime threats as far from shore as possible’ (MDA Citation2020). BlueHawk is only one component of a larger trend and is represented by MDA’s extensive product suite focused on geointelligence and geospatial analytics marketed towards state security efforts. For example, MDA advertises that ‘With tools that detect change, identify objects, classify events and examine trends, we can track ice floes, route ships, monitor crops for growers, map wetlands for ecologists, detect pollution for environmental scientists, spot illegal deforestation for governments and keep an eye on military mobilization’ (MDA Citation2023). Moreover, MDA is also working with DND on developing an electronic warfare system for Canada’s next generation military ships, where this system will aim to ‘improve the intelligence and warning systems that protect the men and women of the Royal Canadian Navy during security, counter-terrorism, counter-piracy, search and rescue, and peacekeeping operations around the world’ (MDA Citation2023).

As a whole, global threats to the Arctic and the state are deployed as structural forces requiring the expansion of security outward spatially and temporally to mitigate vulnerability and adapt to those threats. Conceptually, this points to the notion of pushing sovereignty outward as a technique of pre-emptive power. Research and development efforts focused on the innovation of technology are oriented towards modernising the Arctic through the state’s ability to watch over and enforce its sovereign power at the gaps and seams of its northern territory, which includes an awareness of threats emerging outside of Canada’s national borders. The notion of states extending their power beyond the limits of their territories is not new. However, the idea of ‘pushing out’ sovereignty as the increasingly powerful ability to resolve a territory’s spatial and temporal boundaries and control events within and beyond those boundaries indicates novel techniques of state power applied through the volumetric increase of sensing efforts (including vertically, such as through ground penetrating radar and drones) as a greater sociotechnical approximation of Foucault’s perfect sovereign (see Jones and Johnson Citation2016; Kendall Citation2017).

Conclusion

This paper offers a novel contribution to the burgeoning literature on Arctic security and provides an intervention to understanding Canada’s past and current interest in Arctic-focused sensing technology, which has largely avoided critical investigation by researchers. Specifically, the paper has argued that technological development for Arctic surveillance and security can be historically situated within a long line of state-led efforts spanning the 20th century. Importantly, this strategic thinking indicates the need to create and integrate as many sensors as possible for all domain awareness to respond to the proliferation of complex threats emerging across the world. Canada’s Arctic is considered uniquely vulnerable because of its extensive coastline and the intersection of other trends, including climate change and geopolitical competition.

Sociotechnical imaginaries are collective visions of the future interlaced with notions of scientific progress and advancement towards achieving or navigating that future. Sociotechnical imaginaries provide a unique framing mechanism for understanding how the Arctic was historically presented as a future frontier to be tamed through scientific progress within a broader lens of economic expansion and modernisation that populated the early 20th century and post-war vision. The Cold War entailed a more overtly securitised imaginary, whereas the 21st-century Arctic entails different combinations of earlier imaginaries within a contemporary field of expanded threats and opportunities, ultimately culminating in the New Arctic. Others have already defined the New Arctic, but in this context, it is the sociotechnical expression of multiple international and global trends underpinned by a particular interaction of forces. Sociotechnical imaginaries involve ontological and epistemological issues. State-led efforts towards enhancing sensing abilities in the Arctic represent a specific epistemic approach to an ontology of complexity, which resists easy and direct intervention. The empirical material discussed in this paper is not exhaustive and should not be seen as overly authoritative. However, as a whole, that material demonstrates a consistent approach to understanding the contemporary Arctic environment, and the interaction of efforts in the marine and space domains illustrate this approach to Arctic security.

Thus, the Arctic imaginaries of the present echo some aspects of the past. However, while the imaginary of the past portrayed the Arctic frontier as a space that would ultimately be conquered through science and technological superiority, the contemporary frontier dissolves in the face of science and technology because it is those same forces that undermine the Arctic’s environmental integrity and expose it to extra-sovereign interventions. As with any sociotechnical imaginary, imagined futures often encounter the limits of technology, including its socioeconomic valorisation in the world. The earlier sociotechnical imaginary of a ‘Canada of the North’ never materialised for many reasons, including the technical and economic realities of building northern infrastructure. It is within this wider sociotechnical lens that sensing technologies gain their currency and form, especially as they are an attractive policy goal that is malleable to multiple and possibly contradictory sociotechnical imaginaries of the Arctic’s future.

Sociotechnical imaginaries thus amount to more than simple representations and (re)produce relations of power that circumscribe the dominant ontological foundations of the world. Consequently, the New Arctic is shaping forms of state intervention and governance. This paper has argued that the Arctic is a region considered within a relational worldview premised on complexity and risk, which makes future threats increasingly challenging to predict.Consequently, the New Arctic requires techniques of sovereign power and governance that can make sense of this environment. These techniques depend on technological innovation related to advances in sensing capability because the sheer complexity of this environment overwhelms human cognition.

This paper demonstrates how the New Arctic is a sociotechnical imaginary shaping the development of sensing technologies designed for sovereign enforcement through the example of space-based surveillance capabilities and the use of intelligence applications like the BlueHawk product. While the Arctic represents a unique space where these technologies are being developed and deployed, the proliferation of sensing represents a much larger trend in geostrategic thinking. However, current efforts are only possible within the contemporary security landscape’s broader social and political context. A recent evolution in that thinking flows from the Russian invasion of Ukraine and involves the acceleration of debates on what it means for Arctic governance. This issue speaks to the re-internationalisation of Arctic security alongside its globalisation, intensifying the complexity and intensity of those issues. Future research should engage with this trend more substantially, particularly as Canada’s focus on Arctic sensing aligns with US and NORAD strategic thinking for continental defence and as sensing technology intersects with other developments in artificial intelligence and quantum. Overall, the cases discussed here offer one example of a much larger trend in defence thinking, and technological development centred on integrating global sensor architectures to pre-emptively secure the Arctic of today from the world of tomorrow.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the editor and several anonymous reviewers who provided extensive comments on earlier drafts of this paper. The author would also like to acknowledge the help of Jon Careless and Ryan Kelpin for their advice and feedback on earlier iterations of this work.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Benjamin T. Johnson

Benjamin T. Johnson is an Assistant Professor of Humane Artificial Intelligence and International Relations in the department of International Relations and International Organizations (IRIO) at the University of Groningen, Netherlands. He can be reached at [email protected].

References

- Alessa, L., S. Moon, D. Griffith, and A. Kliskey. 2017. Report of the Emerging Arctic Security Threats Matrix (EarthX) for Improved Canada-United States (CANUS) Arctic Security Workshop. Arctic Security Workshop. Center for Resilient Communities, University of Idaho.

- Alessa, L., S. Moon, D. Griffith, and A. Kliskey. 2018. “Operator Driven Policy: Deriving Action from Data Using the Quadrant Enabled Delphi (QED) Method.” Homeland Security Affairs. September. Accessed January, 2023. https://www.hsaj.org/articles/14586.

- Amoore, L. 2013. The Politics of Possibility: Risk and Security Beyond Probability. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Atran, S. 2006. “A Failure of Imagination (Intelligence, WMDs, ‘Virtual Jihad’.” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 29 (3): 285–300.

- Beck, U. 1992. Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity. London: Sage.

- Bielby, L. M. 2019. “2019 RCMArctic Security Conference Panel 1: Arctic Defence and Security Challenges.” 2019 Royal Canadian Military Institute Arctic Security Conference. April 24. Accessed January, 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UlWlmXQuI78.

- Borgerson, S. 2008. “Arctic Meltdown.” Foreign Affairs 87 (2): 63–67.

- Buffet, S., C. Cherry, C. Dai, A. Désilets, H. Guo, D. McDonald, S. Jiang, and D. Tulpan. 2017. “Arctic Maritime Awareness for Safety and Security (AMASS): Final Report.” September. Accessed February 2, 2023. https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2018/rddc-drdc/D68-3-C319-2017-eng.pdf.

- Buzan, B., O. Wæver, D. Jaap, and W. 1998. Security: A New Framework for Analysis. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

- Cameron, E. 2012. “Securing Indigenous Politics: A Critique of the Vulnerability and Adaptation Approach to the Human Dimensions of Climate Change in the Canadian Arctic.” Global Environmental Change 22 (1): 103–114.

- Chandler, D. 2018. Ontopolitics in the Anthropocene: An Introduction to Mapping, Sensing and Hacking. New York: Routledge.

- Chartier, D. 2018. What is the Imagined North? Ethical Principles. Montréal (Canada): Presses de l’Université duQuébec.