ABSTRACT

Invasive meningococcal disease (IMD) caused by Neisseria meningitidis is characterized by high mortality and morbidity. While IMD incidence peaks in both infants and adolescents/young adults, carriage rates are often highest in the latter age groups, increasing IMD risk and the likelihood of transmission. Effective vaccines are available for 5 of 6 disease-causing serogroups. Because adolescents/young adults represent a significant proportion of cases, often have the highest carriage rate, and have characteristically low vaccination adherence, efforts should be focused on educating this population regarding long-term consequences of infection and the importance of meningococcal vaccination in prevention. This review describes the role of adolescents/young adults in meningococcal transmission and the clinical consequences and characteristics of IMD in this population. With a focus on countries with advanced economies that have specific meningococcal vaccination recommendations, the epidemiology of meningococcal disease and vaccination recommendations in adolescents/young adults will also be discussed.

Introduction

Meningococcal disease is caused by the obligate human bacterium Neisseria meningitidis.Citation1 At least 12 distinct serogroups exist, of which serogroups A, B, C, W, X, and Y are the most common causes of IMD.Citation1 While respiratory tract infection with N meningitidis often leads to a period of asymptomatic nasopharyngeal carriage, in certain conditions, the bacteria can escape the mucosal barrier and replicate in the blood, which can rapidly lead to serious illness and death.Citation1,Citation2

Table 1. Meningococcal vaccines currently licensed for use in adolescents and young adults in countries with advanced economies.*

Table 2. Clinical recommendations for meningococcal vaccination of adolescents and young adults in advanced economies.*

Figure 1. Incidence of meningococcal disease in adolescents by country.Citation14,Citation33,Citation34,Citation45,Citation46

*Data are for invasive meningococcal disease.For the United States, data by age group are for the Active Bacterial Core Surveillance areas (California [3-county San Francisco Bay area], Colorado [5-county Denver area], Connecticut, Georgia, Maryland, Minnesota, New Mexico, New York [15-county Rochester and Albany areas], Tennessee [20 counties]) excluding Oregon. Data for the general population are for national estimates reported to the National Notifiable Disease Surveillance System.

![Figure 1. Incidence of meningococcal disease in adolescents by country.Citation14,Citation33,Citation34,Citation45,Citation46*Data are for invasive meningococcal disease.For the United States, data by age group are for the Active Bacterial Core Surveillance areas (California [3-county San Francisco Bay area], Colorado [5-county Denver area], Connecticut, Georgia, Maryland, Minnesota, New Mexico, New York [15-county Rochester and Albany areas], Tennessee [20 counties]) excluding Oregon. Data for the general population are for national estimates reported to the National Notifiable Disease Surveillance System.](/cms/asset/9bd1ea70-2bee-405b-9ca1-abce09d82f97/khvi_a_1528831_f0001_c.jpg)

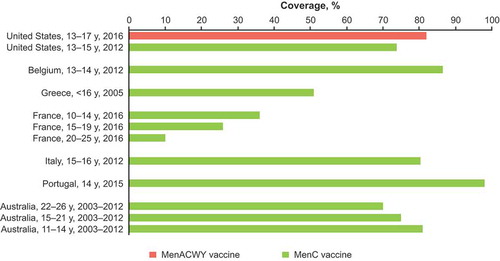

Figure 2. Coverage of meningococcal vaccines in adolescents.Citation54,Citation119–Citation125

MenC = Meningococcal serogroup C conjugate vaccine; MenACWY = quadrivalent meningococcal conjugate vaccine.

Meningococcal disease occurs worldwide;Citation3 however, disease is generally uncommon, with < 5 annual cases per 100,000 persons in countries with advanced economies with meningococcal vaccination programs.Citation4–Citation6 Meningococcal disease clusters have also been reported in such countries, including France,Citation7 the Netherlands,Citation8 Canada,Citation9 Australia,Citation10 Ireland,Citation11 and the United Kingdom.Citation12 Meningococcal disease outbreaks, defined as multiple disease cases in a population attributed to the same serogroup over a short time period, have also occurred (eg, 44 cases per 100,000 students occurred during a US college outbreak in February 2015 compared with the US national incidence of 0.15 cases per 100,000 persons aged 17–22 years).Citation13

Meningococcal disease rates vary with age, with the highest rates typically observed among infants; a second peak in incidence occurs in adolescents and young adults,Citation2,Citation3 with this population accounting for approximately one-third of total cases in some countries (eg, Austria, Czech Republic, Finland, and Sweden in 2016).Citation14 However, N meningitidis acquisition does not always cause disease and often results in asymptomatic colonization of the upper respiratory tract mucosa, a phenomenon known as carriage.Citation2 Although meningococcal disease is generally considered uncommon,Citation4–Citation6 carriage rates are relatively high, typically ranging from 10% to 35% in the general population.Citation15 Although infants bear the greatest burden of disease, the highest carriage rates are often observed in adolescents and young adults (based on data from European countries in which serogroup B and C disease predominate).Citation16 Therefore, improving vaccine availability, adherence to vaccination schedules, and promoting vaccination education in this age group should be goals in countries with significant meningococcal disease burden.

Vaccines are available to protect against 5 of the 6 predominant disease-causing meningococcal serogroups. Justification for vaccination of adolescents and young adults to protect against meningococcal disease includes countering waning immunity after childhood vaccination and achieving herd effects with high vaccine coverage in adolescents and young adults.Citation17 Thus, this age group is an important target for disease control through vaccination.Citation17

The purpose of this review is to describe the role of adolescents in N meningitidis transmission and the clinical consequences and characteristics of meningococcal disease in this age-based population. With a focus on countries with advanced economiesCitation18 that have specific recommendations in this population (ie, Australia, Canada, Europe, New Zealand, and the United States), the epidemiology of meningococcal disease in adolescents and the importance of meningococcal vaccination of this population will be considered.

Role of adolescents and young adults in N meningitidis transmission

Transmitted through respiratory secretions, N meningitidis is often asymptomatically carried at the mucosal surface of the nasopharynx.Citation2,Citation19 This process, known as carriage, is a prerequisite for the development of IMD. One of the most consistently identified risk factors for meningococcal nasopharyngeal carriage is age,Citation19 with the highest carriage rates often observed in adolescents and young adults.Citation16 In a systematic review and meta-analysis of data from 89 studies from European countries or countries in which meningococcal serogroup B (MenB) and meningococcal serogroup C (MenC) predominate, adolescents and young adults were determined to have the highest carriage rates of any age-based population, peaking at a point estimate of 23.7% for those aged 19 years.Citation16

Characteristic social behaviors and not age appear to be largely responsible for the meningococcal carriage increase observed in adolescents and young adults,Citation20 with high N meningitidis carriage rates thought to result partly from social behaviors that increase transmission risk, such as dormitory or military barrack habitation, visiting bars, intimate kissing, and smoking.Citation2,Citation16,Citation17,Citation21 Carriage rates can rapidly increase among college students early in the school yearCitation22 and can vary according to environmental conditions.Citation23 Other factors associated with increased carriage risk include respiratory tract infections, socioeconomic status, and number and closeness of social contacts.Citation20,Citation24

This risk of increased transmission in adolescents and young adults is supported by epidemiologic analyses finding a rapid increase in meningococcal carriage in the first month of the academic year, when university or college students are participating in social behaviors that aid in pathogen spread.Citation22 Adolescents and young adults also are frequent travelers, which exposes them to meningococcal strains prevalent in other countries;Citation25 few seek professional healthcare advice before international travel.Citation26 High carriage rates in this population increase the likelihood of transmission and ultimately disease among adolescents and young adults as well as other age groups.Citation17

Clinical consequences and characteristics of meningococcal infection in adolescents

Meningococcal disease develops rapidly, has a high mortality rate, and can cause serious and long-term complications in survivors.Citation1 The most common IMD manifestations are meningitis and septicemia, which can occur concomitantly.Citation27,Citation28 Signs and symptoms of meningitis in children aged > 5 years include headache, neck stiffness, fever, vomiting, photophobia, rash, irritability, agitation, drowsiness, and seizures.Citation28 In children and adolescents, septicemia typically manifests as lower limb pain, cold peripheries, and skin pallor; rash is a classic sign of meningococcal septicemia, occurring in 40% to 80% of cases.Citation28

Adolescents display a different clinical disease pattern than infants and typically have less rapid disease progression.Citation27,Citation29 For example, a 2006 study characterizing symptoms according to time from onset found that early symptoms specific to adolescents (aged 15–16 years) are common to other self-limiting viral illnesses, including headache, sore throat, and thirst, followed by general aches and fever within 5 to 8 hours.Citation29 Within 9 to 12 hours of onset, signs and symptoms in adolescents include drowsiness, difficulty breathing, diarrhea, neck stiffness, rash, and photophobia, as well as clinical symptoms of sepsis, such as leg pain, cold hands and feet, and abnormal skin color. Confusion/delirium, unconsciousness, and seizures typically occur 24 hours after onset. The authors note that leg pain, cold hands and feet, and abnormal skin color are signs of early meningococcal disease in adolescents, occurring within 12 hours of onset, and should be considered for early identification of disease rather than classic symptoms (eg, rash, meningism, unconsciousness, fever), which occur later in the adolescent disease course.Citation29 Notably, the median time from onset to hospital admission was longer in adolescents (22 hours in those aged 15–16 years) compared with younger children (13–14 hours in those aged < 1–4 years), suggesting that adolescents with meningococcal disease obtain medical attention later than young children, which might have detrimental effects on outcomes in adolescents.

Other studies note that signs and symptoms of meningococcal disease in older children are similar to those in adults and include fever, nausea, vomiting, photophobia, headache, agitation, decreased consciousness, and neck stiffness; seizures and focal neurologic signs are less commonly observed in older versus younger children.Citation27 Recently, meningococcal serogroup W (MenW) clonal complex 11 (cc11) has been responsible for several adolescent cases characterized by gastrointestinal presentations, including nausea, abdominal pain, vomiting, and diarrhea.Citation30

Despite antibiotic treatment for IMD, the case fatality rate (CFR) for meningococcal disease in the general population of many advanced economies (ie, Australia, Canada, Europe, New Zealand, and the United States) remains high (ranging from a CFR of 2.7% in New Zealand in 2016 to 13.9% in the United States in 2016).Citation5,Citation14,Citation31–Citation34 CFRs for meningococcemia are considerably higher (up to 40%).Citation5 CFRs in adolescents and young adults are comparable with those of the general population. Based on the latest epidemiologic data reporting CFRs by age group in the United States, Europe, and New Zealand, CFRs in adolescents and young adults range from 8% to 12.5%.Citation14,Citation35,Citation36 CFRs in adolescents can also vary by serogroup.Citation37 For instance, CFRs in adolescents in Quebec, Canada, between 1990 and 1994 were much higher for MenC than MenB disease (14% vs 7%). A similar finding was found in Australia between 1999 and 2015, with higher CFRs for MenC than MenB disease (6% vs 2%) in adolescents and young adults aged 15 to 24 years.Citation38

Among survivors of meningococcal infection, up to 20% suffer serious and long-term physical and psychological sequelae.Citation39,Citation40 In a study of IMD outcomes in adolescents and young adults (aged 16–22 years), sequelae were reported in 58% of 101 cases and included skin scarring (18%), vertigo (17%), mobility problems (13%), speech problems (13%), hearing problems (12%), upper limb function impairment (4%), amputations (3%), and seizures (2%).Citation41 In addition, 28% of cases had symptoms consistent with Raynaud’s disease, and 41% to 53% reported that IMD affected leisure activities, physical abilities, academic achievements, home life, friendships, and job choices. Compared with age- and sex-matched controls, adolescents who survived IMD reported greater fatigue, decreased social support, reduced quality of life, and poorer educational outcomes, in addition to previously described memory, attention, and psychomotor speed limitations. Younger adolescents also showed a greater degree of cognitive deficit compared with older adolescents, which was thought to be attributable to the vulnerability of the developing brain to acute infections in younger adolescents. In a questionnaire-based study of IMD survivors published in 1998, approximately a quarter of whom were aged 10 to 19 years, many respondents reported decreases in quality of life and increased anxiety.Citation37

Epidemiology of meningococcal disease

Provision of relevant vaccination programs requires not only safe and effective vaccines against meningococcal disease but also consideration of contemporary surveillance data to identify at-risk populations and the prevalent disease-causing serogroups at a given time. Epidemiologic data for meningococcal disease indicate that although a general decline has been observed globally, IMD continues to be a concern in adolescents and young adults in countries with advanced economies. For example, outbreaks of meningococcal disease are uncommon and account for < 2% of all cases of meningococcal disease in the United States; however, adolescents and young adults are at increased risk when outbreaks do occur.Citation42 This may be partly attributed to lack of routine meningococcal vaccination against some disease-causing serogroups,Citation43 typical social behaviors,Citation2,Citation16,Citation17,Citation21 and high carriage rates.Citation16 Mass gathering events have also been linked with meningococcal outbreaks in adolescents. For instance, the 2015 World Boy Scout Jamboree in Japan culminated in 6 MenW cases among attendees aged 15 to 17 years from Scotland and Sweden.Citation44

Overall incidence rates of meningococcal disease in adolescents and young adults compared with the general population vary geographically. However, in countries with advanced economies, incidence rates are typically higher in older adolescents and young adults than in the general population ().Citation14,Citation33,Citation34,Citation45,Citation46 In Australia, Canada, Europe, New Zealand, and the United States, the incidence of meningococcal disease is approximately 1.5- to 3-fold higher in older adolescents/young adults than in the general population based on the most recent surveillance data. The highest incidence of meningococcal disease among older adolescents and young adults in these countries was in older adolescents (aged 15–19 years) in New Zealand (3.1 cases per 100,000 population in 2016)Citation33 and the lowest in younger adolescents (aged 11–15 years) in the United States (0.04 cases per 100,000 population in 2016).Citation34

Meningococcal serogroup B is one of the most common causes of meningococcal disease in several countries with advanced economies, including Australia,Citation31 Canada,Citation32 Europe,Citation14 New Zealand,Citation33 and the United States,Citation47 and, compared with the general population, disproportionately affects older adolescents and young adults in AustraliaCitation38 and the United States.Citation34 MenB disease has also been the cause of recent outbreaks at college campuses in the United States,Citation47 outbreaks in nursery and high schools,Citation48–Citation50 and a family cluster of disease in Europe.Citation51 An increase in MenW disease owing to endemic expansion of a single type cc11 has been observed across all age groups in England, Wales, and the Netherlands.Citation12,Citation52,Citation53 In England and Wales, among those aged 5 to 19 years, cases of MenW cc11 increased from 3 in 2008/2009 to 15 in 2013/2014 compared with 21 in 2008/2009 and 98 in 2013/2014 across all ages.Citation12 In the Netherlands, the number of cases of MenW disease across all age groups increased by 418% from 2014/2015 to 2015/2016, with 55% (29/53 cases) being MenW cc11. An increase in the number of MenW c11 cases was observed in adolescents and young adults; however, the greatest increased burden was in the elderly.Citation53 In additional countries, including France,Citation54,Citation55 Spain,Citation56 Sweden,Citation57 Scotland,Citation57 and Australia,Citation58 an increasing number of cases due to MenW cc11 has been observed recently, and in some countries have been associated with adolescents/young adults and older age groups.Citation53–Citation55,Citation57

Meningococcal vaccination of adolescents and young adults

Various formulations of meningococcal vaccines are available, with the first formulations developed nearly 50 years ago.Citation59 Four types of meningococcal vaccines targeting various serogroups have been used in the last decade: outer membrane vesicle (OMV), polysaccharide, conjugate, and recombinant protein.Citation60,Citation61 Polysaccharide vaccines were the first introduced, in the 1970s,Citation62 followed by OMV vaccines targeting specific MenB disease-causing strains in the late 1980s,Citation61 conjugate vaccines in the late 1990s,Citation63 and recombinant protein MenB vaccines consisting of proteins found on the bacterial surface in the current decade.Citation60 However, polysaccharide vaccines are no longer manufactured, as conjugate vaccines, in which the polysaccharide is conjugated to a carrier protein, were found to be more effective in children aged < 2 years.Citation60,Citation63 Meningococcal vaccines currently available in Australia, Canada, Europe, New Zealand, and the United States are listed in .Citation60,Citation63–Citation86

Several examples of the positive effects of vaccinating adolescents with meningococcal vaccines are available. For instance, vaccination of adolescents in the United States with a quadrivalent vaccine against serogroups A, C, W, and Y (MenACWY) decreased meningococcal disease due to serogroups C, W, and Y by 80% among those aged 11 to 19 years.Citation1 Similarly, following inclusion of monovalent MenC and MenACWY vaccines in routine childhood and adolescent vaccination programs between 2002 and 2007, the incidence of MenC disease in the Canadian general population decreased by 93% and the incidence of IMD overall decreased by 55%,Citation32 indicative of both direct and indirect (herd) effects of vaccination. In addition, following an increase in the number of cases of MenB disease attributed to a particular virulent strain in the 1990s, New Zealand provided vaccination with a MenB OMV to those aged < 20 years between 2004 and 2006, resulting in a 90% decrease in disease attributed to the epidemic strain by 2010.Citation87 In the United Kingdom, routine adolescent MenC vaccination was replaced in the 2015/2016 school year with MenACWY vaccination in response to an increase in MenW cases in addition to a catch-up campaign for adolescents (aged 14–18 years) and new university entrants (aged ≤ 25 years).Citation88 After the first year of the campaign, those specifically targeted for vaccination showed a decline in MenW cases.Citation88

As adolescents and young adults are the primary carriers of meningococci, vaccination of this population can also decrease meningococcal carriage and transmission, inducing herd protection.Citation17 For instance, a national vaccination campaign in the United Kingdom using a conjugate MenC vaccine in infants, children, and adolescents resulted in a statistically significant decrease in the prevalence of MenC carriage in adolescents aged 15 to 19 years lasting at least 2 years and resulting in 75% vaccine effectiveness against carriage.Citation89 However, vaccination of other age-based populations does not appear to confer herd effects in adolescents. The importance of vaccine uptake has also been demonstrated in France, where routine vaccination against MenC was recommended for infants and a catch-up for those aged 2 to 24 years.Citation90 However, the lack of adequate vaccine coverage, particularly among adolescents and young adults, was thought to have resulted in a lack of herd effect. Currently, the application of available meningococcal vaccination recommendations is suggested, with a stress on the importance of adolescents and young adults both for direct protection and for herd effects.

Current recommendations for meningococcal vaccination of adolescents and young adults

With the exception of vaccine-preventable diseases that occur specifically in adolescence and beyond, the goal of vaccination strategies in adolescents without chronic medical conditions is often to boost protective immune responses for vaccines previously administered during infancy and childhood.Citation91 Specifically for meningococcal vaccines, given the seriousness of IMD because of its complications and the increased risk of carriage and disease in adolescents, many advanced economies recommend vaccination of this population against meningococcal disease, often as part of routine primary or booster immunizations or as a catch-up immunization if adolescents were not previously vaccinated at a younger age ().Citation92–Citation97

Recommendations for meningococcal vaccination are dependent on specific characteristics of a country, including individual policies and funding considerations, as well as the overall incidence and frequency of outbreaks in that region. In addition, meningococcal recommendations usually vary depending on the locally prevalent serogroup.Citation98 For instance, in the United States, MenB accounts for approximately 56% of meningococcal disease cases in those 11 to 23 years of age.Citation34 The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), which provides expert external advice and guidance on vaccine use to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC),Citation43 recommends routine vaccination of all adolescents aged 11 to 18 years with a MenACWY vaccine.Citation96 A single dose should be administered as a primary dose at age 11 or 12 years, with a booster dose at age 16 years for those who received the first dose before age 16. ACIP also recommends the routine use of a MenB vaccine in those aged ≥ 10 years who are at increased risk of disease, including those who have persistent complement component deficiencies, anatomic or functional asplenia, or are routinely exposed to isolates of N meningitidis or exposed to a community experiencing a MenB disease outbreak (category A recommendation made for all persons in an age- or risk-factor–based group).Citation97 In addition, MenB vaccination should be considered in individuals aged 16 to 23 years for short-term protection against MenB disease (category B recommendation for individual clinical decision making).

In Canada, MenB is the most common cause of IMD in the general population, accounting for 63% of cases from 2011 to 2015.Citation32 In adolescents aged 15 to 19 years, the most common causes of IMD from 2006 to 2011 were serogroups B and Y.Citation99 In Canada, dependent on provincial epidemiology and programs, routine use of either a conjugate MenC or MenACWY is recommended for adolescents and young adults from 12 to 24 years of age, even if previously vaccinated during early childhood.Citation93 Several Canadian provinces have recently elected to provide conjugate MenACWY vaccines to children and adolescents in response to an increase in cases covered by the vaccine.Citation100–Citation107 Similar to ACIP recommendations, vaccination against MenB is recommended on an individual basis for adolescents and young adults in Canada.Citation93

In Europe, adolescents and young adults aged 15 to 24 years experience the greatest burden of IMD of all age-based populations, accounting for 18.7% of cases in 2016.Citation14 MenB is the most common cause of IMD in individuals 15 to 24 years of age, accounting for 52.1% of cases in 2016, followed by MenC (18.0% of cases) and MenW (16.0% of cases).Citation14 As such, several European countries recommend MenACWY and MenB meningococcal vaccination for adolescents.Citation94 In the United Kingdom, a MenACWY conjugate vaccine is recommended for individuals aged 13 to 25 years.Citation108 MenACWY vaccination is recommended for adolescents aged 11 to 13 years in Austria, 11 to 12 years in Greece, and 12 to 18 years in Italy.Citation94 MenC vaccination is recommended for adolescents aged 12 to 13 years in Ireland, 12 years in Spain, and 19 years in Poland; vaccination in Poland is not mandatory.Citation94 The Czech Republic recommends routine vaccination with MenACWY in adolescents aged 13 to 17 years and with both MenACWY and MenB vaccines for individuals aged ≥ 18 years, but vaccination is not mandatory.Citation94

In Australia, MenB disease predominated from 2002 to 2015, accounting for 43% to 78% of cases each year; however, MenW became the predominant disease-causing serogroup in 2016.Citation31 In 2017, MenB accounted for 36% of cases and MenW for 37% of cases in Australia. The Australian Department of Health currently recommends MenB vaccination for adolescents aged 15 to 19 years, particularly for those living in close quarters, such as military accommodation or student residential accommodation, but does not recommend MenACWY as part of routine vaccination of healthy adolescents and young adults.Citation92 However, a MenACWY vaccination campaign was initiated in 2016, during which the vaccine was offered to adolescents aged 15 to 19 years living in areas with a MenW outbreak.Citation109–Citation112

In New Zealand, older adolescents (aged 15–19 years) have one of the highest rates of meningococcal disease among age-based groups.Citation33 In 2016, the most common cause of meningococcal disease was MenB. The New Zealand Ministry of Health recommends that MenACWY or MenC vaccination be considered for adolescents and young adults living or planning to live in communal accommodation, including hostels, student residences, boarding school, military accommodation, or correctional facilities.Citation95 Of note, MenB vaccines are not currently licensed in New Zealand.

Adherence of adolescents and young adults to recommended vaccination schedules

Although recommendations for use of meningococcal vaccines in adolescents and young adults exist in various countries with advanced economies,Citation43,Citation96,Citation97,Citation108,Citation113–Citation115 low vaccination adherence, particularly to multidose schedules, is common in this age group.Citation116–Citation118 Improving vaccination rates among adolescents and young adults can help decrease outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases and associated economic and societal costs and can improve herd protection.Citation118 However, ensuring that adolescents and young adults adhere to recommended vaccination schedules can be challenging. The decreased frequency in which adolescents visit healthcare providers and difficulty in communicating and obtaining consent from the adolescent or parent/guardian also contribute to nonadherence with recommended vaccine schedules.Citation17 These challenges can result in lower vaccine coverage in adolescents compared with younger age groups.Citation17

Meningococcal vaccine coverage in adolescents varies by country and vaccine type ().Citation54,Citation119–Citation125 The highest coverage for MenC vaccine was reported in Portugal in 2015 in adolescents aged 14 years (98%),Citation124 and the lowest coverage was observed in France in 2016 in young adults aged 20 to 25 years (10%).Citation126 MenACWY coverage in adolescents was only reported in the United States, with 82% of adolescents aged 13 to 17 years receiving MenACWY in 2016.Citation119

A recent systematic review found that strategies to increase vaccination uptake among adolescents, including mandatory vaccination in schools and reminder distribution for adolescent vaccination, can considerably improve vaccine coverage and have led to significant decreases in the prevalence of associated diseases in this population.Citation118 Adherence by adolescents and young adults to recommended vaccine schedules might also improve by decreasing the number of vaccine doses required. In the United States, vaccination against MenB infection among adolescents might improve given the availability of 2 meningococcal serogroup B vaccines (MenB-4C; MenB-FHbp) that can be administered as a 2-dose series.Citation127

Concomitant administration of meningococcal vaccines with other recommended vaccines might also improve coverage in adolescents and young adults.Citation128 The CDC notes that meningococcal conjugate and MenB vaccines can be administered during the same office visit but preferably at different injection sites.Citation129 Coadministration of meningococcal vaccines with other vaccines routinely recommended for adolescents also is possible, as no clinically relevant interactions have been observed.Citation63,Citation128,Citation129 Concomitant administration also does not affect vaccine immunogenicity, as shown in studies of healthy adolescents in whom MenB-FHbp was coadministered with tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis (Tdap); Tdap/inactivated polio virus; or quadrivalent human papilloma virus vaccines.Citation130–Citation132 Simplified vaccination schedules can result in fewer healthcare visits and vaccine doses,Citation133 which could facilitate adherence by reducing logistical challenges and resources needed and increasing vaccine acceptability for providers, parents/guardians, and adolescents.

Educating healthcare providers and the general population about the risks of IMD and carriage in adolescents, available vaccines, and recommended vaccination schedules could also increase adherence. In one study, overall meningococcal vaccination rates increased among first-year college students who received educational materials before arriving on campus.Citation134 In France, where vaccinations typically are administered during visits to a general practitioner or pediatrician, meningococcal coverage rates are low.Citation135 In a survey of French general practitioners, only 33% routinely recommended MenC vaccination for their patients aged 2 to 24 years.Citation135 An educational campaign for healthcare providers and the general population, which can include information on meningococcal vaccine recommendations, benefits of vaccination, and risk of meningococcal disease in adolescents, might help increase meningococcal coverage rates and adherence.Citation135

Summary

Adolescents and young adults are at increased risk of meningococcal disease in many countries. Individuals in this age group are also the most common reservoir for transmission of N meningitidis. Several countries recommend routine vaccination of adolescents against meningococcal disease, with specific recommendations varying by local epidemiologic considerations, individual policies, and funding considerations. Benefits of meningococcal vaccination of adolescents and young adults include decreased rates of IMD and the potential for diminished nasopharyngeal carriage. Further data are needed regarding methods to improve adherence to vaccination schedules and coverage in this age group.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

All authors are employees of Pfizer Inc.

Acknowledgments

Editorial support was provided by Tricia Newell, PhD, of Complete Healthcare Communications, LLC (North Wales, PA), a CHC Group Company, and was funded by Pfizer Inc.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Cohn A, MacNeil J. The changing epidemiology of meningococcal disease. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2015;29(4):667–677. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2015.08.002.

- Stephens DS, Greenwood B, Brandtzaeg P. Epidemic meningitis, meningococcaemia, and Neisseria meningitidis. Lancet. 2007;369(9580):2196–2210. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61016-2.

- Jafri RZ, Ali A, Messonnier NE, Tevi-Benissan C, Durrheim D, Eskola J, Fermon F, Klugman KP, Ramsay M, Sow S, et al. Global epidemiology of invasive meningococcal disease. Popul Health Metr. 2013; 11(1):11–17.doi:10.1186/1478-7954-11-17.

- Trotter CL, Ramsay ME. Vaccination against meningococcal disease in Europe: review and recommendations for the use of conjugate vaccines. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2007;31(1):101–107. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6976.2006.00053.x.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Meningococcal disease. [ accessed 2018 Jun 12]. http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/downloads/mening.pdf.

- Environmental Health Indicators New Zealand. Notifications of meningococcal disease. [accessed 2017 Oct 2]. http://www.ehinz.ac.nz/assets/Factsheets/Released-2015/EHI72-NotificationsOfMeningococcalDiseaseInNZ1997-2014-released201508.pdf.

- Mounchetrou Njoya I, Deghmane A, Taha M, Isnard H, Du Chatelet IP. A cluster of meningococcal disease caused by rifampicin-resistant C meningococci in France, April 2012. Euro Surveill. 2012;17(34). pii: 20254

- Hoebe CJ, de Melker H, Spanjaard L, Dankert J, Nagelkerke N. Space-time cluster analysis of invasive meningococcal disease. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10(9):1621–1626. doi:10.3201/eid1009.030992.

- Le Guerrier P, Pilon P, Sauvageau C, Deshaies D. Spatio-temporal cluster of cases of invasive group B Neisseria meningitidis infections on the island of Montreal. Can Commun Dis Rep. 1997;23(4):25–28.

- Jelfs J, Jalaludin B, Munro R, Patel M, Kerr M, Daley D, Neville S, Capon A. A cluster of meningococcal disease in western Sydney, Australia initially associated with a nightclub. Epidemiol Infect. 1998;120(3):263–270.

- Maoldomhnaigh CO, Drew RJ, Gavin P, Cafferkey M, Butler KM. Invasive meningococcal disease in children in Ireland, 2001-2011. Arch Dis Child. 2016;101(12):1125–1129. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2015-310215.

- Ladhani SN, Beebeejaun K, Lucidarme J, Campbell H, Gray S, Kaczmarski E, Ramsay ME, Borrow R. Increase in endemic Neisseria meningitidis capsular group W sequence type 11 complex associated with severe invasive disease in England and Wales. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60(4):578–585. doi:10.1093/cid/ciu881.

- Soeters HM, McNamara LA, Whaley M, Wang X, Alexander-Scott N, Kanadanian KV, Kelleher CM, MacNeil J, Martin SW, Raines N, et al. Serogroup B meningococcal disease outbreak and carriage evaluation at a college - Rhode Island, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(22):606–607.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Disease data from ECDC Surveillance Atlas for meningococcal disease. [accessed 2018 Jun 25]. https://ecdc.europa.eu/en/meningococcal-disease/surveillance-and-disease-data/atlas.

- Read RC. Neisseria meningitidis; clones, carriage, and disease. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20(5):391–395. doi:10.1111/1469-0691.12647.

- Christensen H, May M, Bowen L, Hickman M, Trotter CL. Meningococcal carriage by age: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10(12):853–861. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70251-6.

- Vetter V, Baxter R, Denizer G, Safadi MA, Silfverdal SA, Vyse A, Borrow R. Routinely vaccinating adolescents against meningococcus: targeting transmission & disease. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2016;15(5):641–658. doi:10.1586/14760584.2016.1130628.

- International Monetary Fund. World economic outlook: Cyclical upswing, structural change. Washington (DC): International Monetary Fund; 2018.

- Soriano-Gabarro M, Wolter J, Hogea C, Vyse A. Carriage of Neisseria meningitidis in Europe: a review of studies undertaken in the region. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2011;9(9):761–774. doi:10.1586/eri.11.89.

- MacLennan J, Kafatos G, Neal K, Andrews N, Cameron JC, Roberts R, Evans MR, Cann K, Baxter DN, Maiden MC, et al. Social behavior and meningococcal carriage in British teenagers. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12(6):950–957. doi:10.3201/eid1206.051297.3201/eid1206.051297.3201/eid1206.051297.3201/eid1206.051297.

- Bruce MG, Rosenstein NE, Capparella JM, Shutt KA, Perkins BA, Collins M. Risk factors for meningococcal disease in college students. JAMA. 2001;286(6):688–693.

- Neal KR, Nguyen-Van-Tam JS, Jeffrey N, Slack RC, Madeley RJ, Ait-Tahar K, Job K, Wale MC, Ala’Aldeen DA. Changing carriage rate of Neisseria meningitidis among university students during the first week of term: cross sectional study. BMJ. 2000;320(7238):846–849.

- Palmgren H. Meningococcal disease and climate. Glob Health Action. 2009;2. doi:10.3402/gha.v2i0.2061

- Caugant DA, Maiden MC. Meningococcal carriage and disease–population biology and evolution. Vaccine. 2009;27(suppl 2):B64–70. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.04.061.

- Steffen R. The risk of meningococcal disease in travelers and current recommendations for prevention. J Travel Med. 2010;17(suppl):9–17. doi:10.1111/j.1708-8305.2010.00449.x.

- Heywood AE, Zhang M, MacIntyre CR, Seale H. Travel risk behaviours and uptake of pre-travel health preventions by university students in Australia. BMC Infect Dis. 2012;12:43. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-12-43.

- Bosis S, Mayer A, Esposito S. Meningococcal disease in childhood: epidemiology, clinical features and prevention. J Prev Med Hyg. 2015;56(3):E121–124.

- Pace D, Pollard AJ. Meningococcal disease: clinical presentation and sequelae. Vaccine. 2012;30(suppl 2):B3–B9. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.12.062.

- Thompson MJ, Ninis N, Perera R, Mayon-White R, Phillips C, Bailey L, Harnden A, Mant D, Levin M. Clinical recognition of meningococcal disease in children and adolescents. Lancet. 2006;367(9508):397–403. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)67932-4.

- Campbell H, Parikh SR, Borrow R, Kaczmarski E, Ramsay ME, Ladhani SN. Presentation with gastrointestinal symptoms and high case fatality associated with group W meningococcal disease (MenW) in teenagers, England, July 2015 to January 2016. Euro Surveill. 2016;21(12). doi:10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2016.21.12.30175.

- Australian Government Department of Health. Invasive meningococcal disease national surveillance report with a focus on MenW. [ accessed 2018 Mar 5]. https://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/5FEABC4B495BDEC1CA25807D001327FA/$File/Sept-2017-IMD-Surveillance-report.pdf.

- Vaccine preventable disease. Surveillance report to December 31, 2015. Ottowa, ON, Canada: Public Health Agency of Canada; 2017.

- The Institute of Environmental Science and Research Ltd. Notifiable diseases in New Zealand: Annual report. 2016. [ accessed 2018 Apr 25]. https://surv.esr.cri.nz/PDF_surveillance/AnnualRpt/AnnualSurv/2016/2016AnnualNDReportFinal.pdf.

- Enhanced meningococcal disease surveillance report, 2016. Hyattsville, MD: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2017.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommended immunization schedules for persons aged 0 through 18 years–United States. 2016. [ accessed 2016 Nov 30]. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/downloads/child/0-18yrs-child-combined-schedule.pdf.

- Lopez L, Sherwood J, Institute of Environmental Science and Research. The epidemiology of meningococcal disease in New Zealand in 2013. [ accessed 2018 Mar 14]. https://surv.esr.cri.nz/PDF_surveillance/MeningococcalDisease/2013/2013AnnualRpt.pdf.

- Erickson L, De Wals P. Complications and sequelae of meningococcal disease in Quebec, Canada, 1990-1994. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26(5):1159–1164.

- Archer BN, Chiu CK, Jayasinghe SH, Richmond PC, McVernon J, Lahra MM, Andrews RM, McIntyre PB. Australian technical advisory group on immunisation meningococcal working P. Epidemiology of invasive meningococcal B disease in Australia, 1999-2015: priority populations for vaccination. Med J Aust. 2017;207(9):382–387.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Meningococcal disease: Diagnosis, treatment, and complications. [ accessed 2017 Nov 29]. https://www.cdc.gov/meningococcal/about/diagnosis-treatment.html.

- Meningitis Research Foundation. After effects. [ accessed 2017 Mar 17]. http://www.meningitis.org/disease-info/after-effects.

- Borg J, Christie D, Coen PG, Booy R, Viner RM. Outcomes of meningococcal disease in adolescence: prospective, matched-cohort study. Pediatrics. 2009;123(3):e502–e509. doi:10.1542/peds.2008-0581.

- Brooks R, Woods CW, Benjamin DK Jr., Rosenstein NE. Increased case-fatality rate associated with outbreaks of Neisseria meningitidis infection, compared with sporadic meningococcal disease, in the United States, 1994-2002. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43(1):49–54. doi:10.1086/504804.

- Cohn AC, MacNeil JR, Clark TA, Ortega-Sanchez IR, Briere EZ, Meissner HC, Baker CJ, Messonnier NE. Centers for disease C, prevention. Prevention and control of meningococcal disease: recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2013;62(RR–2):1–28.

- Smith-Palmer A, Oates K, Webster D, Taylor S, Scott KJ, Smith G, Parcell B, Lindstrand A, Wallensten A, Fredlund H, et al. Outbreak of Neisseria meningitidis capsular group W among scouts returning from the World Scout Jamboree, Japan, 2015. Euro Surveill. 2016;21(45). doi:10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2016.21.45.30392.

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Notifiable disease charts. [ accessed 2018 Jun 25]. http://dsol-smed.phac-aspc.gc.ca/notifiable/charts-list.

- Australian Government Department of Health. National notifiable diseases surveillance system. Notification rate of meningococcal disease (invasive)*, Australia, 2018 by age group and sex. [ accessed 2018 Jun 28]. http://www9.health.gov.au/cda/source/rpt_5.cfm.

- Atkinson B, Gandhi A, Balmer P. History of meningococcal outbreaks in the United States: implications for vaccination and disease prevention. Pharmacotherapy. 2016;36(8):880–892. doi:10.1002/phar.1790.

- Chatt C, Gajraj R, Hawker J, Neal K, Tahir M, Lawrence M, Gray SJ, Lucidarme J, Carr AD, Clark SA, et al. Four-month outbreak of invasive meningococcal disease caused by a rare serogroup B strain, identified through the use of molecular PorA subtyping, England, 2013. Euro Surveill. 2014;19(44). doi:10.2807/1560-7917.ES2014.19.44.20949.

- Stewart A, Coetzee N, Knapper E, Rajanaidu S, Iqbal Z, Duggal H. Public health action and mass chemoprophylaxis in response to a small meningococcal infection outbreak at a nursery in the West Midlands, England. Perspect Public Health. 2013;133(2):104–109. doi:10.1177/1757913912439928.

- Tzanakaki G, Kesanopoulos K, Yazdankhah SP, Levidiotou S, Kremastinou J, Caugant DA. Conventional and molecular investigation of meningococcal isolates in relation to two outbreaks in the area of Athens, Greece. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2006;12(10):1024–1026. doi:10.1111/j.1469-0691.2006.01521.x.

- Acheson P, Barron R, Borrow R, Gray S, Marodi C, Ramsay M, Waller J, Flood T. A cluster of four cases of meningococcal disease in a single nuclear family. Arch Dis Child. 2012;97(3):248–249. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2011-301074.

- National Institute for Public Health and the Environment: Ministry of Health WaS. Meningococcal disease in the Netherlands: Background information for the Health Council. [ accessed 2018 Mar 5]. https://www.rivm.nl/dsresource?objectid=bc885ef5-793e-49e9-a275-18483989d62b&type=pdf&disposition=inline.

- Knol MJ, Hahne SJM, Lucidarme J, Campbell H, de Melker HE, Gray SJ, Borrow R, Ladhani SN, Ramsay ME, van der Ende A. Temporal associations between national outbreaks of meningococcal serogroup W and C disease in the Netherlands and England: an observational cohort study. Lancet Public Health. 2017;2(10):e473–e482. doi:10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30157-3.

- Santé Publique France. Les infections invasives à méningocoques en 2016. Centre National de Référence des méningocoques, Institut Pasteur. [ accessed 2018 Apr 10]. http://invs.santepubliquefrance.fr/content/download/140827/509158/version/3/file/BilanIIM2016.pdf.

- Bassi C, Taha MK, Merle C, Hong E, Levy-Bruhl D, Barret AS, Mounchetrou Njoya I. A cluster of invasive meningococcal disease (IMD) caused by Neisseria meningitidis serogroup W among university students, France, February to May 2017. Euro Surveill. 2017;22(28). doi:10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2017.22.28.30574.

- Abad R, Medina V, Stella M, Boccadifuoco G, Comanducci M, Bambini S, Muzzi A, Vázquez JA. Predicted strain coverage of a new meningococcal multicomponent vaccine (4CMenB) in Spain: analysis of the differences with other European countries. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0150721. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0150721.

- Lucidarme J, Scott KJ, Ure R, Smith A, Lindsay D, Stenmark B, Jacobsson S, Fredlund H, Cameron JC, Smith-Palmer A, et al. An international invasive meningococcal disease outbreak due to a novel and rapidly expanding serogroup W strain, Scotland and Sweden, July to August 2015. Euro Surveill. 2016;21(45). pii: 30395. doi:10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2016.21.45.30395.

- Australian Government Department of Health. Australian meningococcal surveillance programme annual report. 2015. 40. http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/cda-pubs-annlrpt-menganrep.htm.

- Artenstein MS, Gold R, Zimmerly JG, Wyle FA, Schneider H, Harkins C. Prevention of meningococcal disease by group C polysaccharide vaccine. N Engl J Med. 1970;282(8):417–420. doi:10.1056/NEJM197002192820803.

- Immunization Action Coalition. Meningococcal: questions and answers. Information about the disease and vaccines. [ accessed 2017 Nov 29]. http://www.immunize.org/catg.d/p4210.pdf.

- Holst J, Oster P, Arnold R, Tatley MV, Naess LM, Aaberge IS, Galloway Y, McNicholas A, O’Hallahan J, Rosenqvist E, et al. Vaccines against meningococcal serogroup B disease containing outer membrane vesicles (OMV): lessons from past programs and implications for the future. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2013;9(6):1241–1253. doi:10.4161/hv.24129.

- Artenstein AW, LaForce FM. Critical episodes in the understanding and control of epidemic meningococcal meningitis. Vaccine. 2012;30(31):4701–4707. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.04.024.

- Crum-Cianflone N, Sullivan E. Meningococcal vaccinations. Infect Dis Ther. 2016;5(2):89–112. doi:10.1007/s40121-016-0107-0.

- Prymula R, Szenborn L, Silfverdal SA, Wysocki J, Albrecht P, Traskine M, Gardev A, Song Y, Borys D. Safety, reactogenicity and immunogenicity of two investigational pneumococcal protein-based vaccines: results from a randomized phase II study in infants. Vaccine. 2017;35(35Pt B):603–4611. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.07.008.

- Ministerio de Salud (Republica Argentina). Calendario Nacional de Vacunación 2017. [ accessed 2018 Mar 14]. http://www.msal.gob.ar/index.php/programas-y-planes/184-calendario-nacional-de-vacunacion-2016.

- Menveo (Meningococcal Group A, C, W135 and Y conjugate vaccine). Summary of product characteristics. Sovicille (Italy): GSK Vaccines S.r.l.; 2014.

- Menveo (Meningococcal (Groups A, C, Y and W-135) Oligosaccharide Diphtheria CRM197 Conjugate Vaccine). Full prescribing information. Sovicille (Italy): Gsk Vaccines, Srl; 2017.

- Menactra (Meningococcal (Groups A, C, Y and W-135) Polysaccharide Diphtheria Toxoid Conjugate Vaccine). Full prescribing information. Toronto (Ontario, Canada): Sanofi Pasteur Limited; 2017.

- Menactra (Meningococcal (Groups A, C, Y and W-135) Polysaccharide Diphtheria Toxoid Conjugate Vaccine). Full prescribing information. Macquarie Park (NSW, Australia): Sanofi-Aventis Australia Pty Ltd; 2018.

- Menactra (Meningococcal (Groups A, C, Y and W-135) Polysaccharide Diphtheria Toxoid Conjugate Vaccine). Full prescribing information. Auckland (New Zealand): Sanofi-Aventis New Zealand Pty Ltd; 2015.

- Menactra (Meningococcal (Groups A, C, Y and W-135) Polysaccharide Diphtheria Toxoid Conjugate Vaccine Solution for Intramuscular Injection). Full prescribing information. Swiftwater (PA): Sanofi Pasteur Inc; 2018.

- Nimenrix (Meningococcal polysaccharide serogroups A, C, W-135 and Y conjugate vaccine). Full prescribing information. West Ryde (NSW, Australia): Prizer Australia Pty Ltd; 2017.

- Nimenrix (Meningococcal polysaccharide groups A, C, W-135 and Y conjugate vaccine). Full prescribing information. Auckland (New Zealand): Pfizer New Zealand Limited; 2018.

- NIMENRIX (meningococcal polysaccharide serogroups A, C, W-135 and Y conjugate vaccine). Summary of product characteristics. Sandwich (Kent, UK): Pfizer Limited; 2017.

- Bexsero (MenB-4C). Full prescribing information. Abbotsford (Victoria, Australia): GlaxoSmithKline Australia Pty Ltd; 2017.

- Bexsero (MenB-4C). Mississauga (Ontario, Canada): GlaxoSmithKline Inc; 2017.

- Bexsero® (4CMenB). Summary of product characteristics. Uxbridge (Middlesex, UK): GlaxoSmithKline; 2017.

- Bexsero (Meningococcal Group B Vaccine). Full prescribing information. Sovicille (SI) (Italy): GSK Vaccines, Srl; 2018.

- Trumenba full prescribing information. West Ryde (NSW, Australia): Pfizer Australia Pty Ltd; 2017.

- Trumenba (Meningococcal group B vaccine [Bivalent recombinant lipoprotein (rLP2086)]). Full prescribing information. Kirkland (Quebec, Canada): Pfizer Canada Ltd; 2018.

- Trumenba (MenB-FHbp). Summary of product characteristics. Sandwich (UK): Pfizer Ltd; 2017.

- Trumenba (Meningococcal Group B Vaccine). Full prescribing information. Philadelphia (PA): Pfizer Inc; 2018.

- Menjugate (Meningococcal Group C–CRM197 Conjugate Vaccine). Full prescribing information. Mississauga (Ontario, Canada): GlaxoSmithKline Inc; 2017.

- NEISVAC-C (Meningococcal group C polysaccharide conjugate vaccine (tetanus toxoid protein conjugate)). Full prescribing information. Auckland (New Zealand): Pfizer New Zealand Limited; 2015.

- NeisVac-C Vaccine (Meningococcal Group C-TT Conjugate Vaccine, Adsorbed). Full prescribing information. Kirkland (Quebec, Canada): Pfizer Canada Ltd; 2015.

- Menitorix (Haemophilus influenzae type b polyribose ribitol phosphate and serogroup C meningococcal polysaccharide conjugate vaccine (Hib-MenC)). Full prescribing information. Abbotsford (Victoria, Australia): GlaxoSmithKline Australia Pty Ltd; 2016.

- New Zealand Ministry of Health. Meningococcal B immunisation programme and MeNZB™ vaccine. [ accessed 2018 Jun 29]. https://www.health.govt.nz/our-work/preventative-health-wellness/immunisation/immunisation-programme-decisions/meningococcal-b-immunisation-programme-and-menzbtm-vaccine.

- Campbell H, Edelstein M, Andrews N, Borrow R, Ramsay M, Ladhani S. Emergency meningococcal ACWY vaccination program for teenagers to control group W meningococcal disease, England, 2015-2016. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017;23(7):1184–1187. doi:10.3201/eid2307.170236.

- Maiden MC, Ibarz-Pavon AB, Urwin R, Gray SJ, Andrews NJ, Clarke SC, Walker AM, Evans MR, Kroll JS, Neal KR, et al. Impact of meningococcal serogroup C conjugate vaccines on carriage and herd immunity. J Infect Dis. 2008;197(5):737–743. doi:10.1086/527401.

- Haut Conseil de la Santé Publique. Meningococcal vaccine C. [ accessed 2017 Aug 17]. http://www.hcsp.fr/explore.cgi/avisrapportsdomaine?clefr=593.

- World Health Organization. WHO recommendations for routine immunization - summary tables (Table 1). [ accessed 2017 Apr 28]. http://www.who.int/immunization/policy/immunization_tables/en/.

- The Australian immunisation handbook. 10th edition. Canberra, Australia: Australian Government Department of Health; 2017.

- Government of Canada. Canadian Immunization Guide: Part 4 -Active Vaccines. [ accessed 2018 Jul 1]. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/canadian-immunization-guide.html.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Recommended immunisations for meningococcal disease. [ accessed 2017 Jul 20]. http://vaccine-schedule.ecdc.europa.eu/Pages/Scheduler.aspx.

- Immunisation handbook 2017. 2nd edition. Wellington, New Zealand: New Zealand Ministry of Health; 2018.

- MacNeil JR, Rubin L, Folaranmi T, Ortega-Sanchez IR, Patel M, Martin SW. Use of serogroup B meningococcal vaccines in adolescents and young adults: recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(41):1171–1176. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6441a3.

- Patton ME, Stephens D, Moore K, MacNeil JR. Updated recommendations for use of MenB-FHbp serogroup B meningococcal vaccine — advisory committee on immunization practices, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(19):509–513. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6619a6.

- Ali A, Jafri RZ, Messonnier N, Tevi-Benissan C, Durrheim D, Eskola J, Fermon F, Klugman KP, Ramsay M, Sow S, et al. Global practices of meningococcal vaccine use and impact on invasive disease. Pathog Glob Health. 2014;108(1):11–20. doi:10.1179/2047773214Y.0000000126.

- Li YA, Tsang R, Desai S, Deehan H. Enhanced surveillance of invasive meningococcal disease in Canada, 2006-2011. Can Commun Dis Rep. 2014;40(9):160–169.

- BC Centre for Disease Control. HealthLinkBC. Meningococcal quadrivalent vaccines. Number 23b. [ accessed 2017 Oct 3]. https://www.healthlinkbc.ca/healthlinkbc-files/meningococcal-quadrivalent-vaccines.

- Alberta Health. Routine immunization schedule. [ accessed 2017 Oct 3]. www.health.alberta.ca/health-info/imm-routine-schedule.html.

- Government of Saskatchewan. Immuization Services. [ accessed 2017 Oct 2]. www.saskatchewan.ca/residents/health/accessing-health-care-services/immunization-services.

- Government of Ontario. Publicly funded immunization schedules for Ontario – December. 2016. [accessed 2017 Oct 3]. http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/immunization/docs/immunization_schedule.pdf.

- Government of New Brunswick. Routine immunization schedule. [ accessed 2017 Oct 3]. http://www2.gnb.ca/content/dam/gnb/Departments/h-s/pdf/en/CDC/Immunization/RoutineImmunizationSchedule.pdf.

- Government of Prince Edward Island. Adult and child immunization in PEI. [ accessed 2017 Oct 2]. www.princeedwardisland.ca/en/information/health-and-wellness/adult-and-child-immunization-pei.

- Government of Nova Scotia. School immunization schedule. [ accessed 2017 Oct 3]. https://novascotia.ca/dhw/cdpc/immunization.asp.

- Government of Newfoundland and Labrador. Meningococcal disease. [ accessed 2017 Oct 3]. http://www.health.gov.nl.ca/health/publichealth/cdc/pdf/Meningococcal_Vaccine_Fact_Sheet.pdf.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Vaccine scheduler. [ accessed 2017 Aug 17]. http://vaccine-schedule.ecdc.europa.eu/Pages/Scheduler.aspx.

- Government of Western Australia. Targeted campaign against meningococcal W. [ accessed 2017 Nov 29]. https://www.mediastatements.wa.gov.au/Pages/Barnett/2016/12/Targeted-campaign-against-meningococcal-W.aspx.

- Victoria State Government Health and Human Services. Meningococcal ACWY Secondary School Vaccine Program in Victoria: Frequently Asked Questions. [ accessed 2017 Aug 17]. http://www.mwsc.vic.edu.au/assets/uploads/2017/05/FAQs-Meningococcal-ACWY-vaccine.pdf.

- NSW Government Health. NSW Meningococcal W Response Program. [ accessed 2017 Aug 17]. http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/Infectious/factsheets/Factsheets/meningococcal-w-program.pdf.

- Queensland Health. Meningococcal ACWY vaccination program. [ accessed 2017 Aug 17]. https://www.health.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0022/640147/faq-meningococcal-acwy-program.pdf.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Meningococcal disease: Surveillance. [ accessed 2017 Nov 29]. https://www.cdc.gov/meningococcal/surveillance/.

- Government of Canada. Canadian immunization guide: Part 4 – active vaccines. [ accessed 2017 Nov 29]. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/healthy-living/canadian-immunization-guide-part-4-active-vaccines/page-13-meningococcal-vaccine.html.

- Australian Government Department of Health. National immunisation program schedule. [ accessed 2017 Nov 29]. http://www.immunise.health.gov.au/internet/immunise/publishing.nsf/Content/nips.

- Gallagher KE, Kadokura E, Eckert LO, Miyake S, Mounier-Jack S, Aldea M, Ross DA, Watson-Jones D. Factors influencing completion of multi-dose vaccine schedules in adolescents: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:172. doi:10.1186/s12889-016-2845-z.

- Reagan-Steiner S, Yankey D, Jeyarajah J, Elam-Evans LD, Singleton JA, Curtis CR, MacNeil J, Markowitz LE, Stokley S. National, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13-17 years–United States, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(29):784–792.

- Das JK, Salam RA, Arshad A, Lassi ZS, Bhutta ZA. Systematic review and meta-analysis of interventions to improve access and coverage of adolescent immunizations. J Adolesc Health. 2016;59(4S):S40–S48. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.07.005.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Teenvaxview. Results for adolescent MenACWY vaccination coverage. [ accessed 2018 Apr 10]. http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/imz-managers/coverage/teenvaxview/data-reports/menacwy/index.html.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National and state vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13-17 years–united States, 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62(34):685–693.

- VaxInfo.org. Epidémiologie. Flandre: Couvertures vaccinales élevées en. 2012. [ accessed 2017 Nov 24]. http://www.vaxinfopro.be/spip.php?article824&lang=fr.

- Kafetzis DA, Stamboulidis KN, Tzanakaki G, Kourea Kremastinou J, Skevaki CL, Konstantopoulos A, Tsolia M. Meningococcal group C disease in Greece during 1993-2006: the impact of an unofficial single-dose vaccination scheme adopted by most paediatricians. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2007;13(5):550–552. doi:10.1111/j.1469-0691.2007.01704.x.

- Pascucci MG, Di Gregori V, Frasca G, Rucci P, Finarelli AC, Moschella L, Borrini BM, Cavrini F, Liguori G, Sambri V, et al. Impact of meningococcal C conjugate vaccination campaign in Emilia-Romagna, Italy. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2014;10(3):671–676.

- Direcção-Geral DS. A Saúde dos Portugueses. Boletim Vacinação. No 10. [ accessed 2017 Nov 24]. https://www.dgs.pt/estatisticas-de-saude/estatisticas-de-saude/publicacoes/a-saude-dos-portugueses-perspetiva-2015-pdf.aspx.

- Lawrence GL, Wang H, Lahra M, Booy R, Mc IP. Meningococcal disease epidemiology in Australia 10 years after implementation of a national conjugate meningococcal C immunization programme. Epidemiol Infect. 2016;144(11):2382–2391. doi:10.1017/S0950268816000704.

- Santé Publique France. Données. Méningocoque C. [ accessed 2017 Nov 24]. http://invs.santepubliquefrance.fr//Dossiers-thematiques/Maladies-infectieuses/Maladies-a-prevention-vaccinale/Couverture-vaccinale/Donnees/Meningocoque-C.

- MacNeil J, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Considerations for use of 2- and 3-dose schedules of MenB-FHbp (Trumenba®). [ accessed 2017 Mar 21]. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2016-10/meningococcal-05-macneil.pdf..

- Gasparini R, Tregnaghi M, Keshavan P, Ypma E, Han L, Smolenov I. Safety and immunogenicity of a quadrivalent meningococcal conjugate vaccine and commonly administered vaccines after coadministration. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2016;35(1):81–93. doi:10.1097/INF.0000000000000930.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Administering meningococcal vaccines. [ accessed 2017 Nov 29]. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/mening/hcp/administering-vaccine.html.

- Vesikari T, Wysocki J, Beeslaar J, Eiden J, Jiang Q, Jansen KU, Jones TR, Harris SL, O’Neill RE, York LJ, et al. Immunogenicity, safety, and tolerability of bivalent rLP2086 meningococcal group B vaccine administered concomitantly with diphtheria, tetanus, and acellular pertussis and inactivated poliomyelitis vaccines to healthy adolescents. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2016;5(2):180–187. doi:10.1093/jpids/piv064.

- Muse D, Christensen S, Bhuyan P, Absalon J, Eiden JJ, Jones TR, York LJ, Jansen KU, O’Neill RE, Harris SL, et al. A phase 2, randomized, active-controlled, observer-blinded study to assess the immunogenicity, tolerability and safety of bivalent rLP2086, a meningococcal serogroup B vaccine, coadministered with tetanus, diphtheria and acellular pertussis vaccine and serogroup A, C, Y and W-135 meningococcal conjugate vaccine in healthy US adolescents. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2016;35(6):673–682. doi:10.1097/INF.0000000000001124.

- Senders S, Bhuyan P, Jiang Q, Absalon J, Eiden J, Jones TR, York LJ, Jansen KU, O’Neill RE, Harris SL, et al. Immunogenicity, tolerability, and safety in adolescents of bivalent rLP2086, a meningococcal serogroup B vaccine, coadministered with quadrivalent human papilloma virus vaccine. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2016;35(5):548–554. doi:10.1097/INF.0000000000001072.

- Dodd D. Benefits of combination vaccines: effective vaccination on a simplified schedule. Am J Manag Care. 2003;9(1 Suppl):S6–12.

- Collins L, Dupont L, Nagle D. The impact of educational efforts on first-year university students’ acceptance of meningococcal vaccine. J Am Coll Health. 2003;52(1):41–43. doi:10.1080/07448480309595722.

- Le Marechal M, Agrinier N, Fressard L, Verger P, Pulcini C. Low uptake of meningococcal C vaccination in France: a cross-sectional nationwide survey of general practitioners’ perceptions, attitudes and practices. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2017;36(7):e181–e188. doi:10.1097/INF.0000000000001553.