Abstract

Objectives: In families with a parent diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), children’s adaptation depends among others on how their parents communicate with them about the disease and its trajectory. The aim of this study was to explore parents’ and children’s perceptions of ALS-related family communication. Methods: A qualitative analysis using a conventional content analysis approach was applied to interview data previously collected from 21 parents (8 with ALS) and 15 children (age 13–23 years) about their experiences living with ALS. Results: Three themes emerged from the interviews: communication topics, styles and timing. Communication topics include facts about disease and prognosis, feelings, care and equipment, and the end. Although most parents perceived the familial communication style concerning ALS as open, the interviews revealed that both parents and children sometimes avoid interactions about ALS, because they do not know what to say or how to open the dialogue, are afraid to burden other family members, or are unwilling to discuss. Communication timing is directed by changes in the disease trajectory and/or questions of children. A family-level analysis showed that ALS-related family communication is sometimes perceived differently by parents and children. Conclusions: The study provides a better understanding of what, how and when parents and children in families living with ALS communicate about the disease. Most families opened the dialogue about ALS yet encountered challenges which may hamper good familial communication. Through addressing those challenges, healthcare professionals may facilitate better communication and adaptation in families with a parent with ALS.

Introduction

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), including progressive muscular atrophy (PMA) and primary lateral sclerosis (PLS), transforms the everyday lives of those affected, as well as their families. Healthcare professionals and numerous medical equipment come into their homes, parents and children take on caregiving tasks, family dynamics are disrupted, and families have to find new ways to spend time together (Citation1–3). Families face the challenge of continuously adjusting their lives – cognitively, emotionally and behaviorally – to a new situation. This process of adjusting is referred to as resilience or adaptation and is critical to maintain a good quality of life (Citation4). Previous work suggests that one key to adaptation lies in how families interact about the disease trajectory (Citation5–12). Familial communication about the disease is of particular importance for children’s adaptation. Timely and open communication between parents and their children about diagnosis, prognosis and treatment may prevent children from creating misconceptions about the disease, help them give meaning to the situation, prepare them for possible outcomes (e.g. caregiving role, loss of parent), and improve children’s psychosocial functioning (Citation6–9,Citation13–15). To be able to support parent-child communication about ALS, it is crucial to understand how parents with ALS and their co-parents communicate with their children about the disease trajectory, prognosis and end of life of the parent with ALS and what challenges they may encounter. To date, parent-child communication has received only little attention in the field of ALS (Citation1,Citation16). The aim of this study was to explore perceptions of disease-related family communication among parents and children living in families with a parent diagnosed with ALS.

Methods

This paper provides a secondary analysis of previously collected data from interviews with 8 parents with ALS, 13 well parents and 15 children (age 13–23 years) from 16 different families (Citation1). Sample characteristics and procedures have been published elsewhere (Citation1). The current study extends the previously published paper by Sommers-Spijkerman et al. (Citation1) by taking an in-depth focus on emergent issues around family communication.

Interview transcripts were screened in its entirety by AS and MSS seeking data reflecting parents’ or children’s perceptions of ALS-related communication. Relevant data were analyzed in NVivo 12 using conventional content analysis (Citation17). After a preliminary review of the data, AS and MSS developed a coding scheme which was discussed with AB and MSK. Codes were revised and refined upon multiple reviews of the data. MSS coded all transcripts with the final coding scheme. Coded sentences or passages were checked for consistency by AB and MSK. Finally, MSS, AB and MSK rearranged and combined codes into themes and subthemes. Themes were analyzed at the level of parents (n = 21), children (n = 15) and families (n = 8). For each theme, 1) parents’ and children’s perceptions of ALS-related family communication were explored and 2) perceptions of parents and children from the same family were compared.

Results

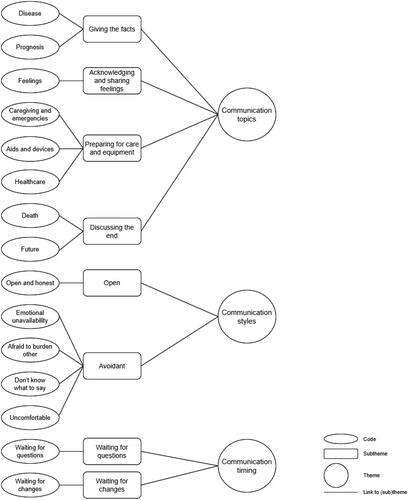

Interview data on ALS-related family communication were clustered into three themes: communication topics, communication styles and communication timing (see and ).

Table 1. Overview of themes and subthemes identified from the interviews.

Communication topics

Both parents and children indicated that ALS-related communication commonly focused on giving the facts about diagnosis and prognosis (e.g. muscles get weaker and stop working, there is no cure). Other topics included acknowledging and sharing feelings and preparing for care and equipment (e.g. preparing children for emergencies, explaining medical aids and equipment). Discussing the end was only mentioned by a few parents and not by children.

Communication styles

The interviews revealed that the majority of parents perceive their communication style as open and honest. Nonetheless, some parents and children seem to avoid interactions about ALS, either in general or specific (sensitive) topics such as euthanasia or heredity, because they 1) do not know how or feel no room to open this conversation, 2) do not know what to say, 3) are afraid to burden other family members (i.e. parents, children or siblings), or 4) feel uncomfortable. Which communication style parents/children adopt seems to depend on multiple factors such as personality, parental comfort, the topic of communication and the age of the children.

Communication timing

While most parents opened the dialogue about ALS immediately or briefly after receiving the diagnosis, some parents already started this conversation prior to the diagnosis to prepare their children for the anticipated bad news. The interviews revealed that parents re-open the conversation following hospital visits, when anticipating adjustments in the home situation (e.g. new equipment), when noticing disease progression or aggravation of symptoms in the parent with ALS (waiting for changes), and when children start asking questions (waiting for questions).

Comparing perceptions at family-level

A comparison of parents’ and children’s perceptions at family-level revealed that, within some families, certain aspects of ALS-related family communication are perceived differently by parents and children. For example, within some families, parents perceived the communication within the family to be open whereas children perceived the communication as closed. provides examples of corresponding and conflicting perceptions per theme.

Table 2. Family-level analysis.

Discussion

This study showed that families with a parent diagnosed with ALS have conversations about the facts, how they feel, care and equipment and/or the end, using both open and avoidant communication styles, and primarily precipitated following developments in the disease trajectory and/or when the child raises questions.

The interviews suggest that the content of ALS-related conversations from parent to child is primarily focused on providing factual or practical information about the disease and care trajectory, and to a lesser extent on psychosocial aspects. To help their children manage everyday life with ALS and prevent them from potential future problem behaviors, it is important that parents not only inform or educate their children about ALS, according to their child’s developmental stage, but also give their children room to express the many emotions they may be experiencing, including anger, sadness, grief and anxiety (Citation1,Citation6,Citation18). Professionals may create awareness among parents about the importance of talking about feelings, and encourage parents to discuss their own feelings as well as to allow their children to express theirs.

In line with previous studies in other palliative diagnoses (Citation1,Citation6–8,Citation13,Citation14), the present study shows that open family communication may be hindered when family members do not know what to say, do not know how to open the dialogue, or are unwilling to discuss. Interviews with parents and children suggest that avoidant communication is often due to an underlying fear, such as the fear to burden or upset other family members, the fear to say things that may not happen or the fear for (not being able to answer) questions. When families are not open, it is important to identify and address those underlying fears that withhold family members from being open to each other. Professionals may also help parents open the dialogue with their children through initiating family conversations and showing families how they can openly and respectfully talk to each other about ALS, including sensitive topics such as the inevitable end of life of the parent with ALS.

Finally, interview findings indicate that the conversation about ALS is re-opened multiple times along with developments in the functioning of the parent with ALS, the home situation and/or the child, suggesting that it is a dynamic and continuous process. ALS care professionals can play a critical role in maintaining continued open communication within families, through regularly assessing if things are changed and if (more) information or support is needed, especially when sensitive topics are to be addressed. It is crucial that the support offered is family-centered. Each family has its own dynamics, communication patterns, norms and values which may influence how parents and children talk about ALS (Citation6). Differences in communication needs and preferences may not only exist between families but also within families, as reflected in the family-level analysis. Thus, first and foremost, professionals may want to encourage parents to inquire and listen and attend to the communication needs of their children (Citation13).

Limitations

The present study poses two major limitations, toning down the potential impact and generalizability of the findings. The interview data used were collected for a previous study (Citation1), which 1) did not primarily aim to address family communication about ALS as a result of which data saturation could not be achieved for all themes, and 2) did not assess cognitive and behavioral functioning of parents with ALS which is likely to impact on how families talk about ALS.

Conclusion

This study provides further insight into what, how and when families communicate about ALS. Although families generally open the dialogue about ALS, they encounter challenges which may hamper good familial communication. Through addressing those challenges, healthcare professionals may facilitate timely and open ALS communication within families which is deemed essential for families’ and especially children’s adaptation to life with ALS. Cultural differences, how families talk about the imminent death of the parent with ALS and the role of cognitive and behavioral impairments in family communication about ALS remain important topics for future research, as well as what types of support parents need to feel well-equipped to discuss ALS and its practical, social and emotional impact with their children.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Sommers-Spijkerman M, Rave N, Kruitwagen-van Reenen E, Visser-Meily JMA, Kavanaugh MS, Beelen A. Parental and child adjustment to amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: transformations, struggles and needs. BMC Psychol. 2022;10:72.

- Kavanaugh MS, Cho CC, Howard M, Fee D, Barkhaus PE. US data on children and youth caregivers in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurology 2020;94:e1452–e9.

- Cipolletta S, Amicucci L. The family experience of living with a person with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a qualitative study. Int J Psychol. 2015;50:288–94.

- Ovaska-Stafford N, Maltby J, Dale M. Literature Review: Psychological resilience factors in people with neurodegenerative diseases. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2021;36:283–306.

- Eklund R, Kreicbergs U, Alvariza A, Lovgren M. Children’s self-reports about illness-related information and family communication when a parent has a life-threatening illness. J Fam Nurs. 2020;26:102–10.

- Dalton L, Rapa E, Ziebland S, Rochat T, Kelly B, Hanington L, et al. Communication with children and adolescents about the diagnosis of a life-threatening condition in their parent. Lancet. 2019;393:1164–76.

- Shea SE, Moore CW. Parenting with a life-limiting illness. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2018;27:567–78.

- Fearnley R, Boland JW. Communication and support from health-care professionals to families, with dependent children, following the diagnosis of parental life-limiting illness: A systematic review. Palliat Med. 2017;31:212–22.

- Lindqvist B, Schmitt F, Santalahti P, Romer G, Piha J. Factors associated with the mental health of adolescents when a parent has cancer. Scand J Psychol. 2007;48:345–51.

- Zaider TI, Salley CG, Terry R, Davidovits M. Parenting challenges in the setting of terminal illness: a family-focused perspective. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2015;9:52–7.

- Barnes J, Kroll L, Burke O, Lee J, Jones A, Stein A. Qualitative interview study of communication between parents and children about maternal breast cancer. Bmj. 2000;321:479–82.

- Weber Falk M, Eklund R, Kreicbergs U, Alvariza A, Lovgren M. Breaking the silence about illness and death: Potential effects of a pilot study of the family talk intervention when a parent with dependent children receives specialized palliative home care. Palliat Support Care. 2022;20:512–8.

- Fearnley R, Boland JW. Parental life-limiting illness: What do we tell the children? Healthcare 2019;7:47.

- Kavanaugh MS, Noh H, Zhang L. Caregiving youth knowledge and perceptions of parental end-of-life wishes in Huntington’s disease. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care. 2016;12:348–65.

- Park EM, Jensen C, Song MK, Yopp JM, Deal AM, Rauch PK, et al. Talking with children about prognosis: The decisions and experiences of mothers with metastatic cancer. JCO Oncol Pract. 2021;17:e840–e7.

- Kavanaugh MS, Henning F, Mochan A. Young carers and ALS/MND: Exploratory data from families in South Africa. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies. 2020;16:123–33.

- Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15:1277–88.

- Howell KH, Barrett-Becker EP, Burnside AN, Wamser-Nanney R, Layne CM, Kaplow JB. Children facing parental cancer versus parental death: The buffering effects of positive parenting and emotional Expression. J Child Fam Stud. 2015;25:152–64.