Abstract

Background: The purpose of this study was to describe how patients with persistent pain experience physiotherapist-guided Free Movement Dance (FMD) as a physiotherapy intervention.

Methods: Individual interviews were conducted with 20 patients who had participated in FMD for 1–6 semesters with different guiding physiotherapists. The interviews were transcribed and analysed using qualitative content analysis with an inductive approach as described by Graneheim and Lundman.

Results: The analysis resulted in one overarching theme—Physiotherapist-guided Free Movement Dance is empowering in everyday living—and five subthemes: Breaking unhealthy patterns generates physical confidence and strength, Developing greater understanding of the body signals, Accepting pain is important but challenging, Taking responsibility for myself and my well-being and Feeling calmer and happier in life.

Conclusions: FMD was experienced as a physiotherapy intervention that enabled the patients to develop an awareness of their own movement, and also leading to the feeling of being empowered in everyday living. FMD can be seen to be in concordance with the core values of physiotherapy that individuals have the capacity to change as a result of their responses to physical, psychological, social and environmental factors.

Introduction

Pain lasting more than three months is defined as persistent pain (PP), [Citation1] and is a common reason to seek a physiotherapist. About 20% of the population in Europe, as well as in the United States, suffer from PP [Citation2,Citation3]. Effective treatments are scarce, although a systematic literature review from 2010 of evidence-based physiotherapy interventions reported strong evidence supporting physical activity in combination with behavioural medicine treatment [Citation4]. Exercise in combination with pain education in a group setting has also been shown to be one effective model [Citation5].

Having pain affects life to a great extent and patients have described the impact of PP on their everyday living to make life not worth living and as pain is the master [Citation6]. The importance of both physical and psychological approaches [Citation7–9] and, of including the biopsychosocial perspective [Citation10] has been stressed, considering the complex interaction of biological, psychological and social factors that need to be addressed in treatment of PP [Citation11,Citation12].

In the process of shifting focus from a strictly biomechanical approach in physiotherapy, Roxendal developed Basic Body Awareness Therapy (BBAT) [Citation13] in the early 1980s and, in the theoretical framework of body awareness she described the levels of human being as physical, physiological, psychological and existential. Although initially mostly used within psychiatric physiotherapy, BBAT is often recommended for treatment of PP. BBAT, was further developed by Gyllensten [Citation14], and aims to normalise posture, balance, breathing and muscular tension [Citation15]. The concept is well-known and used by physiotherapists primarily in Scandinavia. Van der Maas et al. [Citation16] further defined body awareness as a multidimensional construct involving sensitivity and attentiveness to internal body signals as muscle tension and heartbeat, overall body states such as feeling strained or relaxed, and of bodily changes as acceleration of breath or tightening of muscles due to changes in the environment as well as in emotions. Interpreting body signals without negative thoughts and feelings and acting according to this information were found to decrease catastrophizing and was also suggested to increase self-efficacy [Citation16]. Group interventions using BBAT in physiotherapy of PP [Citation17,Citation18], have been experienced as an embodied learning process. Positive experiences of the body were intertwined with a new relationship to self and objects in the world. The interactions between the co-participants promoted the process of creating new patterns of thinking and acting in the social world [Citation17,Citation18].

Furthermore, inspiration from music and movement has been found valuable in treating pain. Music, provided through a portable media player was shown to have an analgesic effect [Citation19] and, listening to music in daily life improved perceived control over pain [Citation20]. It has also been shown that the effectiveness of aerobic exercise was higher when combined with music therapy in improving depression and general discomfort in individuals with fibromyalgia [Citation21]. Movement in the form of dance therapy has been suggested to increase quality of life, decrease physical stress, lead to mental stress reduction and increased body awareness [Citation22]. Thus, both BBAT, music used in therapy and dance therapy seem have a positive impact regarding quality of life on patients suffering from PP.

However, in the field of physiotherapy we still felt that there was a lack of methods built on self-explored movements. To fill this gap Freeing Dance in Mindfulness (FDiM) [Citation23] was considered an interesting method to convert into physiotherapy practise for patients with PP and it was named Free Movement Dance (FMD). FDiM is a way of dancing where the dancers find their own movements to seven different music rhythms: flowing, staccato, chaos, lightness, stillness, shaking and your own dance, and there are no given movement patterns provided by the dance guide. The dance guide in FDiM uses the rhythms to inspire the dancers to be creative and to find new ways of moving their bodies and to practice to be present while moving.

FMD uses the principles of FDiM with the different rhythms and this is combined with the physiotherapists’ extensive knowledge of the body and its movement needs and potential, to determining strategies for diagnosis and intervention [Citation24]. The approach of FDM is self-exploring and carries the potential to give patients insight into their own movement resources so that they learn concrete strategies to implement more functional and economic patterns in their day-to-day routines. FMD is performed in groups and pain management, education and coping strategies has been added as well as verbalising and sharing. The patients with PP are examined and followed up as by usual physiotherapy treatment. The physiotherapist uses the information from examining the patients before the group intervention during FMD and can therefore guide the patients into more functional movements even though the movement is freely chosen by the patient. For example, ‘if your back hurts when you bend forwards, try to find other ways to move which are less painful’. The rhythms and guidance aim at facilitating setting limits and using pacing. Additionally, FMD contributes to psychological flexibility, pain management and acceptance of pain. Appendix shows a deeper understanding of FMD and describes a FMD session.

Table 1. Content and structure of the Free Movement Dance intervention explored in a study of informants’ experiences of the treatment.

Altogether, our clinical experience is that FMD has gained increased interest within physiotherapy, and patients with PP who have participated in group interventions have spontaneously expressed improved health, however this has not been systematically explored. Thus, the aim of this study was to describe how patients with PP experiences physiotherapist-guided FMD as a physiotherapy intervention.

Methods

The study was performed as an interview study, using an empirically grounded method, exploratory in process [Citation25], qualitative design with an inductive approach [Citation26] using qualitative content analysis following the procedure described by Graneheim and Lundman [Citation27]. Qualitative content analysis is said to be on a descriptive, interpretive level, which stays close to the original text [Citation25] and includes both manifest and latent content [Citation28]. The research results should have direct usefulness for the clinic and should not need to be ‘back-translated’ from an abstract level where the results need to be explained again for clinical use. Therefore the method is well suited for the purpose of describing the informants’ experiences of participation in FMD as a physiotherapy intervention.

The researchers are all female and, registered physiotherapists with long clinical experience in treatment of patients with PP mainly within primary care. The first author (KN), holds a master’s degree and is a certified Freeing Dance guide by the Freeing Dance Academy. The second author (AE), also holds a master’s degree and have previous experience of qualitative research. The third author (MEHL) is an associate professor with substantial research experience in both qualitative and quantitative methods.

Setting and participants

A purposeful sampling strategy was used [Citation29] to get a range of informants in age, gender, nascence, cause of pain, diagnoses as well as informants from different groups led by different physiotherapists and various time since participation (). This strategy was chosen to shed light on the experiences of participating in FMD as a physiotherapy intervention from various aspects [Citation30].

Table 2. Informants of Free Movement Dance intervention

To be eligible for inclusion in the interview study, the patients must have been diagnosed with PP, have had participated in FMD as a physiotherapy intervention (could be between 1 and 6 semesters during 2009–2013) and being able to participate in an interview.

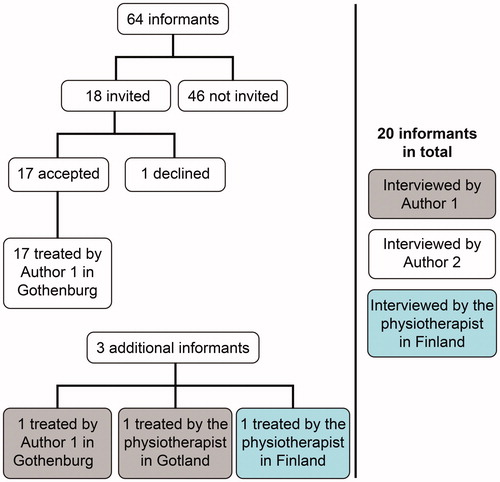

Of 64 people who had participated in the FMD groups at a healthcare centre in Gothenburg, Sweden, 18 were contacted by the second author and were asked whether they wanted to participate in the study. One person chose not to participate with the motivation that it had been too long since the FMD participation. To recruit additional informants, four physiotherapists using FMD were personally contacted (through the Swedish Association of Physiotherapists as well as personal contacts), and three of them contributed with one informant each; one of these informants was recruited from Finland. Altogether, 19 women and 1 man participated in the study as informants. All of the informants had previous history of other physiotherapy interventions for their pain condition and had wanted to try something new.

shows a flow chart of the recruitment process.

Data collection

Before starting to invite patients to participate in the study, three pilot interviews were performed by KN to test the interview guide and discuss its suitability with the other authors of the study. These interviews were not included in the present study.

Patients who agreed to participate in the study were scheduled for an interview. The first interview was conducted in June and the final one in December 2013. The 17 informants from the health care centre were interviewed by AE, who had not been involved in their treatment. Two external informants were contacted by KN and were subsequently interviewed by her, and a third external informant from Finland was interviewed by the physiotherapist who also led the group because of logistics and language. The informants were notified that the interview would be open and focused on their own experiences of FMD as a physiotherapy intervention. The semi-structured, face to-face interviews took place at healthcare facilities, except for one that was performed by telephone. Field notes were written by the interviewer during the interviews. They lasted, on average, 35 min (range: 19–75 min, mean 4670 words, range 2243–7454) and were conducted in an undisturbed environment. The initial question was, ‘How would you describe your experience of FMD?’ Follow-up questions were, for example, ‘Can you tell me more about this experience?’ or ‘How has this experience affected you in your daily life?’ The interviewer tried to cover areas such as the effects of music, leader, group, exercises and different rhythms. However, the questions were open and not specified in advance, in accordance with the interview technique used to gain as rich narratives as possible. All interviews were digitally recorded, and transcribed verbatim. The interview in Finnish was subsequently translated into Swedish by a translator.

Data analysis

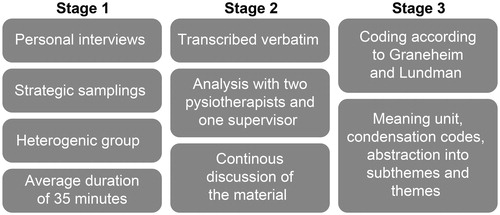

KN and AE performed the analysis with supervision by MEHL. The software NVivo 10 (QSR International Pty Ltd, Doncaster, Victoria, Australia) was used as a tool in this process. The first stage of the analysis was to listen to and read the interviews several times to gain a deeper understanding of the material. The next stage (stage 2) was to identify meaning units (words, sentences and paragraphs). The meaning unit is the base of which the analysis takes a starting point. It is the central meaning of one or several sentences describing experiences related to the aim of the study. In stage three, these meaning units were condensed, which is a process of shortening while still preserving the core, and then coded. The code is the label of the condensed meaning unit. These codes can still be close to the text but they could also be the first abstraction on the material. The codes were cross-checked through the entire texts until agreement was reached by the analysts. In stage four the codes were clustered into subthemes based on how they were related and linked. Finally, (stage 5) the underlying meaning through condensed meaning units, codes and subthemes were abstracted on an interpretative level into an overarching theme. MEHL read the transcripts of the interviews and checked that the process adhered to the guidelines for the analysis method [Citation27]. Differences were discussed by all of the authors until consensus was reached throughout the analysis process to increase the trustworthiness of the study. No new codes emerged in the final interviews. The analysis was performed in Swedish, and the subthemes and theme were then translated into English after completion. ().

The authors of the present study aimed to maintain personal distance and a critical perspective throughout the study [Citation29,Citation30]. Trustworthiness [Citation31] of the study was sought through credibility, dependability and transferability, which also was further explained and exemplified in the article of Graneheim and Lundman [Citation27].

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was sought but waived by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Gothenburg, referring to Swedish law, and only advice was given for the study (reference 411-13). Therefore neither was ethical approval searched for the Finnish informant who participated. However, the informants received both oral and written information about the study and gave their written consent to participate. They were assured that the results would be safely presented so that no individual informant could be recognised. The informants were told that they, at any time, could withdraw from the study without any explanation or future inconvenience when seeking health care.

Results

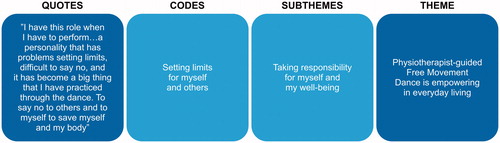

The analysis resulted in a latent overarching theme—Physiotherapist-guided Free Movement Dance is empowering in everyday living—and five subthemes: Breaking unhealthy patterns generates physical confidence and strength, Developing greater understanding of the body signals, Accepting pain is important but challenging, Taking responsibility for myself and my well-being and Feeling calmer and happier in life. The analysis of the raw data was complex, and it was not possible to divide the data into categories that are more separable; thus, the authors used a theme and subthemes [Citation27]. ()

Physiotherapist-guided FMD is empowering in everyday living

To be empowered in everyday living is the main interpretation on a latent level expressed by the informants in various forms and is the underlying meaning of the subthemes. Experiences were described at the physical, psychological, social and existential levels. Explicitly or implicitly across the subthemes, physiotherapist-guided FMD was reported to be empowering in everyday living. Improving physical courage and strength by breaking unhealthy patterns, with guidance and by the presence of the physiotherapist also increased body awareness and helped participants accept the pain, but it was challenging. Taking responsibility for oneself by daring to express oneself among others was empowering, and comfortable movements in the body created a feeling of happiness, security and power in life.

Breaking unhealthy patterns generates physical confidence and strength

Experiences of improvements in strength, endurance, coordination and balance were reported in this subtheme. The ability to move without walking aids, to sit down on the floor and to rise again was regained. The ability to walk longer distances and have more strength for daily activities was also highlighted, and the participants used the method as a home exercise.

The self-exploring movements offered a deeper contact with their bodies and the participants stated that they could even feel deeper layers of muscles such as the stabilising core muscles in FMD. Informants also described being challenged to move painful areas of their bodies which they normally tried to ignore or were afraid to move.

‘I get sick every time I workout, but I feel that after FMD, I don’t get sick afterwards. Sure, I can get a bit hurt, but I won’t be confined to bed, not recently, but in the beginning because I overdid it. But just that it is a good exercise method’ (I: 9).

‘I got an implant in my knee and then it got into my head that I didn’t dare to move or walk properly/./then you played with music and scarves/…/then I dared to let go more and more and walk around in the room and that was a huge feeling that I dared’ (I: 6).

Through awareness of the body, feelings, the breathing and self-explored movements to different rhythms, FMD was described to help to decrease bodily tension and sometimes even pain and to improve sleep.

‘Some tensions are released, and when the tension disappears, what’s left is an empty space in the body, the muscles, the joints, the vertebrae, wherever it is… my whole being is space and more of that freedom… that breathing releases the muscle tensions’ (I: 18).

Developing greater understanding of the body signals

In this subtheme, it was described how guidance by the physiotherapist to be aware of the body and to better understand the body signals was very important. Simply putting on music and dance freely was not perceived to have the same effect as being guided into different anatomical structures as muscles, joints and the nervous system for example by the physiotherapist’s specific knowledge of functional movements. The guidance, rhythms and group were described as necessary ingredients to become more aware of their own bodies.

‘In the dance you learn so much to listen to exactly the whole body/./now I know if it starts to sting in my fingers, then I know I have to take it easy.’ (I: 3)

To experience the pain in the body through conscious self-explored movements also gave insights of how pain was connected to feelings.

‘To dance different parts of the body and then the feelings flared up like I…yes, mmm, I didn’t have a clue that the pain and the feelings belonged together’ (I: 14).

Learning to pace movements, activity and rest was described as a result from the physiotherapist guidance. Both the theoretical knowledge given by the physiotherapist and the dance exercises were described as useful in improving body awareness as well as pacing.

‘I’ve learned to pace my movements, which I have benefitted from, in that I get less tired and therefore have fewer migraines’ (I: 8).

Accepting pain is important but challenging

In this subtheme, it was described how learning to accept the pain was important but very challenging, especially in the beginning. Informants described that ignoring body signals and forcing the body to continue doing activities despite the pain and believing that listening to the pain would be the same as being defeated by it were old habits that were challenged by FMD. This process to find new ways to manage the pain required time and much practice. Imagining the pain as a dance partner was helped them to come into contact and communicate with the pain. This communication was also practiced in everyday situations and led them to pace activities and rest in time. The feeling of being sorry and apologetic for ignoring the pain and a promise to take better care of themselves from now on were expressed.

‘Sometimes it feels like I have a knife in my back and it’s me that has put it there, that I have to do things, I have to perform, I have to fix, I have to, I have to all the time and… that knife, it feels like I almost have taken it out. But I haven’t thrown it away because I want to become friends with it because I still want to do things but I don’t want to feel this pressure and compulsion…I want to make an agreement and compromise with the knife…sounds strange (laughter)… this is a thing that I’ve brought into my daily life…’(I: 4).

Informants expressed how the pain related to many feelings, such as sorrow and anger, and it was frightening to confront these feelings. A sense of fear of drowning in all the feelings and not being able to handle it was described. Memories could appear and seemed to be stored in the pain. Guidance by the physiotherapist was described as helping the informants to overcome the resistance, to dare to feel all those feelings, and to confront memories in a way that led to less tension and, therefore sometimes even less pain.

‘It feels that you are in all the emotions, if you are afraid you are afraid, if you are sad you are sad, if you are happy you are happy, and it is ok to feel whatever you feel; it is ok to be whoever you are’ (I: 9).

‘Thanks to her way of guiding, it became okay that it was a day like today because it was a theme to find acceptance in reality/…/if she hadn’t been so careful to point out… that it was important to accept what is, I don’t think the dance would have brought that by itself’ (I: 16).

The informants described that it was beneficial, as well as difficult and challenging, to move without given movement patterns and to meet all the feelings and memories that appeared when being aware of body and pain.

‘When I started this dance, a lot happened in my body. Because I had never processed the feelings from abuse/…/and when you do these movements, it just appears through my body. And at first, it can be unpleasant, but then you let yourself get swept away with it/…/ok that’s where I got hit….and I work a bit more at that place. I make a movement in a way that I feel… here I will move more to get healthy’ (I: 19).

The rhythms were perceived as helpful to encounter pain and feelings connected with them.

‘Yes, chaos gives me an angry feeling, and I want to stomp with my feet and move sweepingly around and that part when you dance still and calm and just feel stillness and to feel the feeling of angry or black and dark and how it feels to be happy, this nice feeling that you want the most and then you can become sad. Well it’s the dance. You get thoughts about things. You can dance every feeling’ (I: 11).

The use of different coloured scarves provided additional possibilities to express the feelings.

‘If I take a black scarf, it could be dark thoughts and dark feelings and it is dark inside of me’. ‘If I take a red, it might be happy and more outgoing feelings’ (I: 12).

The sharing, verbalising and listening to how the others in the group handled pain were perceived as helpful. It was important to realise that they were not alone in having pain.

‘We sit together afterwards with this stone that goes around and everyone tells what they have experienced. Some choose not to say anything, but many talk about how they have felt and they talk about feelings, or they cry or they…yes it is really very strong to be able to do that in a group’ (I: 12).

‘I got new thoughts and insights from the other members of the group’ (I: 16).

Taking responsibility for myself and my well-being

In this subtheme, it was described that through FMD, awareness was generated of the informants’ own responsibility for themselves and how they very often sacrificed their own well-being to please others. The informants described that they started to put up boundaries and give voice to their opinions more openly in close relationships, at work and in other social situations. They expressed how this led to less tension in their body and, in many cases, to less pain and better sleep. They also expressed an increased self-compassion and that they started to take care of their bodies and listen to the body’s signals instead of ignoring them. The informants described that they became more relaxed in their bodies and in life itself.

‘I just stand there and have a huge pain or that the body just collapses and doesn’t work. I can’t walk, I can’t move, and I get pain or get a huge physical anxiety… and then, then I didn’t know why, but now I have been with my physiotherapist doing FMD so now I have started to discover, oh well…somehow to learn when the body signals oh, oh, oh, now there is something wrong…to stop and see what is happening.’ (I: 17).

‘Today, I felt glad when the others were sad. That was a challenge’ (I: 15).

In the subtheme, it was also expressed how increased self-confidence was found, where the informants were supposed to express with bodily movements their ‘yes’ and ‘no’, their way to strive forward and their goals. This exercise helped the informants to build up the courage to express their opinions, for instance at work. Breaking unhealthy relationships and experiencing less demand in social situations were other results reported.

‘I have had much of that in my life, to adapt to everyone else, do what others think I should do and think about how others look at me… and in the dance, it’s so nice you just close your eyes and you’re allowed to express and it strengthens me in other things that I do. I’ve dared to express myself more at work./…/I believe in myself and that I’m good enough as I am’ (I: 11).

‘A colleague at work was sad/…/and it was very hard to handle for me but I handled it differently than before I joined the FMD… I didn’t have to take away his burden,/…/so I felt that I could be really supportive without taking on his sorrow and I felt it was thanks to the FMD’ (I: 8).

Feeling calmer and happier in life

It was described how a feeling of calmness and happiness appeared when one allowed oneself to relax more. The FMD was experienced as being very playful and setting fantasies and laughter free. Informants expressed how turning on music at home and dancing when they felt stressed helped them to be calmer and connect with feelings of happiness. Awareness of some type of spiritual presence arrived when connecting with calmness and a feeling of freedom appeared. FMD was expressed to offer hope of being able to live a full life despite the pain.

‘I’m so happy and I start getting hopeful again and feel that I will survive this. I really have better self-confidence since I’ve started with FMD’ (I: 9).

‘I don’t need to identify myself with the pain, that when I am just like one who has pain all the time. And despite that I have a body that aches of one reason or another, I can, despite that, be completely alive, happy and cheerful and somehow enjoy my life/…/It is like my body or mind or some inner third that leads not just me but someone else’ (I: 18).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to describe how patients with PP experience FMD as a physiotherapy intervention. The main result was that they felt empowered in everyday living and is the interpretative level of the underlying meanings of the subthemes. The concept empowerment has psychological, social, cultural, economic and political dimensions and can shortly be described as the process of finding power to influence one’s life including taking responsibility for one’s health [Citation32]. However, many health-related problems cannot be solved only on an individual level and consequently it is important to clarify one’s responsibility as well as realise that some problems must be put into a broader context [Citation32]. The task for physiotherapists to promote empowerment is confirmed by Semmonds [Citation33] who also state that patients with PP are advised not to push through pain which will tend to cause ‘wind up’ and increased pain.

Improved physical ability is a common goal within physiotherapy and PP can be an aggravating factor to cope with when being physical active. In the subtheme Breaking unhealthy patterns generates physical confidence and strength, the informants described improved physical ability in strength, endurance, coordination and balance even though they did not learn specific exercises in a structured training schedule to reduce pain. By contrast, the informants in the present study described that exploring free convenient movements was useful and could be included in everyday life. Using rhythms in an exercise programme inspired by Jaques-Dalcroze [Citation34] eurhythmics has been proven to improve physical function and balance as well as cognitive function and mood in older people in a RCT by Trombetti et al [34]. However, this specific exercise regimen involved multiple-task practice and not self-explored movements [Citation34].

The informants’ description of movement as an essential element of health and well-being is in line with the core values of physiotherapy that state that movements are also dependent on the integrated, coordinated function of the human body at several levels [Citation35]. This is reflected in the Movement Continuum Theory of Physical Therapy, where the key concept is movement, and that physiotherapists conceptualise movement on a continuum that incorporates the physical and pathological aspects of movement with social and psychological considerations [Citation36].

Similar results of improved physical ability were found in a qualitative study in which patients with chronic low back pain were interviewed about their experiences of participating in cognitive functional therapy training (CFT) [Citation8]. Although CFT includes more specific exercises for patients with chronic low back pain [Citation37], themes such as ‘changing pain beliefs’ and ‘achieving independence’ were identified. The authors discussed the diversity in outcomes that are linked to the degree to which the patients adopted ‘biopsychosocial beliefs’ and the ability to achieve independent self-management. These outcomes required a strong therapeutic alliance, development of body awareness and the experience of control over pain. Important factors were newly cultivated problem-solving skills, self-efficacy, decreased fear of pain and improved stress coping [Citation8]. Thus, the experience of breaking unhealthy patterns seems to be important for the improvement of physical ability in CFT as well as in FMD, although the methods differ. The great value in targeting kinesiophobia in physiotherapy treatments for patients with PP was also described by Lüning et al. [Citation38].

Therapeutic components in FMD used by the PT to transfer learning are teaching skills as well as subject knowledge to give education about pain, guidance into body awareness, guidance to explore the willingness to accept what is in the present moment, pacing in order to balance activity level. The physiotherapist is using musical rhythms in guiding FMD to facilitate different movement qualities which were perceived helpful and inspiring by the informants. Shaking could, for example, dissolve both physical and mental tension. The experiences of different rhythms were according to the informants helpful in increasing body awareness. In the subtheme Developing greater understanding of the body signals the guidance, rhythms and group were described as necessary ingredients to increase body awareness. Using only music without movements as an intervention for pain management was reported to significantly reduce pain and depression [Citation39]. Another study [Citation21] found that music combined with movements such as aerobics had an even more analgesic effect than just the exercises themselves. This finding is comparable with the results in the present study, where the informants describe the music as an important tool to be inspired to move. Furthermore, using music with specific rhythms is specific for FMD. To illustrate, the informants in this study described the rhythms as helpful to find new moments and explore different movement quality. Chaos could, for example help to let go of control and hereby tension in body and mind. However, the informants found some music to be temporarily provoking instead of the relieving the pain, contrary to the effect reported studies about music therapy.

In contrast to the present study of FMD, the informants in a BBAT study [Citation18] described the coordination of the exercises to be challenging and that they sometimes wanted a specific movement to last longer. According to Gyllensten et al. [Citation15], it is important to recognise one’s needs and emotions to cope with pain, to become familiar with one’s body by being present and experiencing the body from the inside: the breathing, balance, and self-confidence as well as needs and emotions. These aspects were also reported by the informants in the present study and can be found in all the subthemes in different ways. To experience the body from the inside, the breathing, balance (both physical and psychological), self-confidence and needs and emotions is an effective summary of FMD and, according to the informants, it leads to increased body awareness during the session, but also in everyday life. This ability increased the longer they practiced FMD. On the other hand, the informants in the present study also described that they sometimes escaped from the body during FMD sessions and that this distraction technique was a relief to be free from pain for a short while.

The informants described pacing as a strategy to manage the pain in their daily lives. Nevertheless, pacing is, to our knowledge, seldom discussed in research regarding body-oriented therapies, although it is in line with listening to body signals. Jamieson-Lega et al. [Citation40] have defined pacing as an important part of physiotherapy treatment, described as an active self-management strategy whereby individuals learn to balance time spent on activity and rest for the purpose of achieving increased function and participation in meaningful activities.

The concept of acceptance can be seen in psychological approaches such as Acceptance Commitment Therapy (ACT) [Citation41] Previous research suggests that acceptance-based therapies have small to medium effects on physical and mental health in chronic pain patients and that acceptance is a promising alternative to distraction and control techniques in successfully coping with pain [Citation42]. ACT is often used in an educational setting with theoretical oral and written exercises to explore the possibility to live a life with pain according to one’s preferred direction. Results indicate that inclusion of the values component leads to significantly greater pain tolerance than acceptance alone [Citation42]. In the subtheme Accepting pain is important but challenging, the informants in the present study described the challenge of meeting and accepting pain and reported that they experienced many stressful feelings during FMD. To deal with these feelings, in FMD, the physiotherapist guides into acceptance and body awareness. The informants pointed out how important this guidance was. They also expressed that they could feel resistance before the intervention. However, using self-exploring movements in different rhythms to dare to move despite of pain is a unique experience for the informants in the present study and was found to be beneficial in reducing the fear of moving and in accepting pain. Furthermore, the rhythm staccato is in a way related to the value components according to the informants. By offering the possibility to move straight across the room, stop or use different directions they could explore how it feels to be determined or find new directions in life. They were also invited to dance their ‘yes’ and ‘no’ during this rhythm which gave insights in how to find decisiveness in the dance as well as in life. Biguet et al. [Citation43] states that the aspects of acceptance need to be considered during physiotherapy rehabilitation as the meaning given to acceptance is related to the experience of the lived body and the sense of self, as well as getting legitimacy/acceptance by others. The informants expressed appreciation that their physiotherapist could listen to the needs of the group and guide them in accordance with this intuitive listening in the subtheme.

The informants of the present study described that the sub-theme Taking responsibility for myself and my well-being increased self-awareness and that they, through FMD, learned to say no to themselves and to others to save themselves from being too active and paying the high price of more pain afterwards. To maintain body awareness when interacting with others, in family relations and in relations in society is also described by Gyllensten et al. [Citation15]. The group context with socialising was also described as very important by the informants of the present study. They expressed that they found new ways of coping with pain and new insights about their behaviour towards self and others by listening to the others in the group. This result was also found by Olsen and Skjaerven [Citation17], who concluded that physiotherapy treatment in groups can be useful as preparation for daily life situations because a considerable part of life occurs in social settings.

FMD is, in a way, related to DT [Citation22], by providing music and dance. However, in DT, the movements are mostly directed from the therapist to the patient and the therapist analyses how the patients perform the movements and how the movements are connected to psychological aspects. According to the informants in FMD, the self-exploration of movements was beneficial in improving being able to take responsibility for oneself.

The informants described Feeling calmer and happier in life, as a result of participating in FMD. In a study by Dragesund and Råheim [Citation44] using Norwegian psychomotor physiotherapy as an intervention for patients with chronic pain, and with their perspective on body awareness, the participants expressed joy and freedom in their bodies, like parachuting, and a feeling of satisfaction. It seems that there are many different ways to achieve the same results in body awareness; awareness of your own body can bring feelings such as calmness and happiness. Ojala et al. [Citation6], found that using interventions to meet and change negative feelings into more positive ones seems to be very important when treating patients with PP. As FMD was experienced as being very playful and providing a moment of joy by the informants, it may be helpful in creating a more positive view of life. This is in line with the research of Brené Brown, [Citation45] PhD in social work and research professor at the University of Houston. She states that laughter, singing and dancing reminds us of the only thing that really matters when we seek comfort, inspiration, healing or want to express our joy; that we are not alone. Belonging is a basic human need and to be playful a way to experience togetherness.

The informants described experiences at the physical, psychological, social and existential levels which are in line with BBAT’s, theoretical framework [Citation15]. Briefly the informants described that they experienced their physical bodies’ limitations as well as possibilities while moving as well as physiological processes as changes in heartbeat, breathing and temperature. FMD gave rise to different feelings and thoughts and behaviour which led to self-reflection. They identified habit patterns and began to question and change their behaviour. Exploring comfortable movements in the body to different rhythms and sharing in a group created a feeling of happiness, security and power in life. Explicitly or implicitly FMD was reported to be empowering in everyday living. The theory sense of coherence, SOC, by Antonovsky [Citation46], is defined as: ‘The extent to which one has a pervasive, enduring though dynamic, feeling of confidence that one’s environment is predictable and that everything will work out as well as can reasonably be expected’. The pain education and the exploring of free movements gave the informants comprehensibility and increased manageability. The group provided belonging and togetherness, and altogether this gave meaningfulness to their situation.

FMD is in many ways related to existing body awareness treatment methods for treating patients with PP but has a unique quality by being based on free movements to different rhythms. As patients with PP are a very heterogeneous group with different needs, physiotherapists need to widen their treatment arsenal. FMD can fill in the gap in the field for those who want to move to music rhythms without specific given exercises in order to explore their own movements. The physiotherapist guidance into body awareness and acceptance, as well as pain education and an understanding that PP affects not only the body but also thoughts and feelings as well as behaviour, is of great importance when treating PP and are integrated in FMD. There are many ways to address these needs and according to the informants FMD can be one of them.

Trustworthiness of the study was sought through credibility, dependability and transferability [Citation31]. The concepts is also explained and exemplified in the article of Graneheim and Lundman [Citation27]. The interviews were performed by a physiotherapist who was familiar with both the research method and intervention. To avoid bias, she was unknown to the informants. The interviews were conducted within one year and were transcribed directly after the interview. As time since participating in FMD varied, there could be a risk of recall bias; those closer to FMD would probably more clearly remember their experiences of FMD. On the other hand, those more distant may be likely to remember ‘the most important’. As researchers, we should have confidence in our informants; that they remember and talk about their experiences of participating in FMD.

The analytical process started after the first three interviews, which was helpful to further develop and deepen the questions in the subsequent interviews. Analysis triangulation among all three authors was performed to illuminate blind spots and understand multiple ways of seeing the data. The analytical process continued after the last interview, and the material was read and discussed continuously by the authors. The transcribed interviews contained rich and nuanced data with detailed examples of the informants’ experiences. The informants were invited to a presentation of the study at University of Gothenburg 2015 where there were possibilities for them to reflect and discuss the results of the study. About ten informants participated and they agreed with how their experiences of FMD as a physiotherapy intervention were described. Thus, this was another way to create trustworthiness.

Only one man was included, but this is in line with the gender distribution in FMD groups. Informants were also chosen from groups in FMD led by various physiotherapists to determine whether different leaders caused other experiences among the participants.

The interviews were performed and transcribed verbatim in Swedish, except one that was transcribed in Finnish and then translated. There is a risk that some subtleties of the language were lost when translated into English. Translating the Finnish interview first into Swedish and then the meaning units into English increases this risk of loss of information.

Seventeen informants have been treated in the FMD groups led by the first author. Although the first author did not conduct the interviews, the informants were aware of her engagement in the study, and their answers may have been biased to please her. All informants were also aware of the profession of the authors and, as most of the informants found FMD to be very rewarding and wanted it to be spread as a physiotherapy intervention, they might have withheld negative information in the interviews. Another limitation of the study may be that participants who had begun the intervention but discontinued were not interviewed. Although the data collection was performed in 2013, the experiences of the informants are valid.

Conclusions

The informants described how FMD as a physiotherapy intervention was experienced as leading to personal development by being aware and present when performing self-explored movements. FMD gave them insights into both their bodily functions and the connection to their mental state of mind as embodied knowledge. They described how FMD enabled them to facilitate change and developed an awareness of their own needs and goals which led to the feeling of being empowered in everyday living. FMD can be seen to be in concordance with the core values of physiotherapy that individuals have the capacity to change as a result of their responses to physical, psychological, social and environmental factors.

Implication for future research

This study has provided information on patients suffering from PP experiences of FMD. The described experiences seem to have value for the patients and resulting in a feeling of being empowered in everyday living. Yet, further research is needed to confirm this study’ results. It would be interesting to evaluate outcomes of pain, health related quality of life, mood as well as work ability in an RCT comparing FMD to other physiotherapy interventions.

180929_Appendix_Free_Movement_Dance.doc

Download MS Word (51 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the informants for their time and willingness to share their experiences with us. We give thanks to Petra Turja, RPT, Finland for contributing with one informant and performing the interview, Saara Raculjic for translating it from Finnish to Swedish and Anne Hargesson, RPT, for contributing with one informant. We would also like to thank Mats Ekhammar and Mirjana Raculjic for help with graphics. Ingmari and Hans Desaix, Margareta Nordström, Susanne Bernhardsson and Oliver Rogers for proofreading. Martina Slättberg and Ann Heljeback for their support. Last but not least thank you Anne Grundel for creating FDiM.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no declarations of interest.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP). [cited 2018 Jul 6]. Available from: http://www.iasp-pain.org

- Von Korff M. Healthcare for Chronic Pain: Overuse, Underuse, and Treatment Needs Commentary on: Chronic Pain and Health Services Utilization – Is there overuse of diagnostic tests and inequalities in non-pharmacologic methods utilization? Med Care. 2013;51:857–858.

- Merrick D, Sundelin G, Stalnacke BM. One-year follow-up of two different rehabilitation strategies for patients with chronic pain. J Rehabil Med. 2012;44:764–773.

- SBU. The Swedish Council on Health Technology Assessment. Rehabilitation of patients with chronic pain conditions; 2016 [cited 2018 Jul 7]. Avaliable from: http://www.sbu.se/sv/Publicerat/Gul/Rehabilitationofpatientswith-chronic-pain-conditions-/

- Murphy SE, Blake C, Power CK, et al. The effectiveness of a stratified group intervention using the STarTBack screening tool in patients with LBP–a non randomised controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2013;14:342.

- Ojala T, Hakkinen A, Karppinen J, et al. The dominance of chronic pain: a phenomenological study. Musculoskelet Care. 2014;12:141–149.

- Bunzli S, McEvoy S, Dankaerts W, et al. Patient perspectives on participation in cognitive functional therapy for chronic low back pain. Phys Ther. 2016;96:1397–1407.

- Nielsen M, Keefe FJ, Bennell K, et al. Physical therapist-delivered cognitive-behavioral therapy: a qualitative study of physical therapists’ perceptions and experiences. Phys Ther. 2014;94:197–209.

- Simmonds MJ, Derghazarian T, Vlaeyen JW. Physiotherapists’ knowledge, attitudes, and intolerance of uncertainty influence decision making in low back pain. Clin J Pain. 2012;28:467–474.

- Gatchel RJ. Comorbidity of chronic pain and mental health disorders: the biopsychosocial perspective. Am Psychol. 2004;59:795–805.

- Foster NE, Delitto A. Embedding psychosocial perspectives within clinical management of low back pain: integration of psychosocially informed management principles into physical therapist practice–challenges and opportunities. Phys Ther. 2011;91:790–803.

- Laisné F, Lecomte C, Corbière M. Biopsychosocial predictors of prognosis in musculoskeletal disorders: a systematic review of the literature (corrected and republished). Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34:1912–1941.

- Roxendal G. Body awareness therapy and body awareness scale [Thesis]. Faculty of Medicine, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg; 1985.

- Gyllensten A. Basic body awareness therapy [Dissertation]. Lund (Sweden): Departement of Physical Therapy, Lund University; 2001.

- Gyllensten AL, Skär L, Miller M, et al. Embodied identity—A deeper understanding of body awareness. Physiother Theory Pract. 2010;26:439–446.

- Van der Maas LC, Köke A, Pont M, et al. Improving the multidisciplinary treatment of chronic pain by stimulating body awareness: a cluster-randomized trial. Clin J Pain. 2015;31:660–669.

- Olsen AL, Skjaerven LH. Patients suffering from rheumatic disease describing own experiences from participating in basic body awareness group therapy: a qualitative pilot study. Physiother Theory Pract. 2016;32:98–106.

- Mannerkorpi K, Gard G. Physiotherapy group treatment for patients with fibromyalgia—an embodied learning process. Disabil Rehabil. 2003;25:1372–1380.

- Bellieni CV, Cioncoloni D, Mazzanti S, et al. Music provided through a portable media player (iPod) blunts pain during physical therapy. Pain Manag Nurs. 2013;14:e151–e155.

- Linnemann A, Kappert MB, Fischer S, et al. The effects of music listening on pain and stress in the daily life of patients with fibromyalgia syndrome. Front Hum Neurosci. 2015;9:434.

- Espí-López GV, Inglés M, Ruescas-Nicolau M-A, et al. Effect of low-impact aerobic exercise combined with music therapy on patients with fibromyalgia. A pilot study. Complement Ther Med. 2016;28:1–7.

- Koch SC, Bräuninger I. International dance/movement therapy research: theory,methods, and empirical findings. Am J Dance Ther. 2005;27:37–46.

- Grundel A. Frigörande dans i mindfulness. vad händer egentligen? [Freeing Dance in Mindfulness. What is really happening?] Stjärnsund: Frigörande Dans Akademin; 2016.

- World Confederation for Physical Therapy (WCPT). Available from: https://www.wcpt.org/policy/ps-descriptionPT

- Krippendorff K. Content analysis: an introduction to its methodology. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage; 2004.

- Bulmer M. Concepts in the analysis of qualitative data. Sociological Review.1979;27:651–571.

- Graneheim UH, Lundman B. 2004 Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004;24:105–112.

- Downe-Wamboldt B. Content analysis: method, applications, and issues. Health Care Women Int. 1992;13:313–321.

- Patton MQ. Qualitative research & evaluation methods: integrating theory and practice. Thousand Oaks (CA): SAGE Publications; 2015.

- Polit DF, Beck CT. Nursing research: generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice. Philadelphia (PA): Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008.

- Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic inquiry. Newbury Park (London): Sage Publications Inc.; 1985.

- Gibson CH. A concept analysis of empowerment. J Adv Nurs. 1991;16:354–361.

- Semmonds J. The role of physiotherapy in the management of chronic pain. Anaesth Int Care Med. 2016;17:445–447.

- Trombetti A, Hars M, Herrmann FR, et al. Effect of music-based multitask training on gait, balance, and fall risk in elderly people: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:525–533. [PubMed: 21098340]

- Hislop HJ. The not-so-impossible dream. Phys Ther. 1975;55:1069–1080.

- Cott CA. The movement continuum theory of Physical Therapy. Physiother Can. 1995;47:87–95.

- O'Sullivan K, Dankaerts W, O'Sullivan L, et al. Cognitive functional therapy for disabling nonspecific chronic low back pain: multiple case-cohort study. Phys Ther. 2015;95:1478–1488.

- Lüning Bergsten C, Lundberg M, Lindberg P, et al. 2012 Change in kinesiophobia and its relation to activity limitation after multidisciplinary rehabilitation in patients with chronic back pain. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34:852–858.

- Onieva-Zafra MD, Castro-Sánchez AM, Matarán-Peñarrocha GA, et al. Effect of music as nursing intervention for people diagnosed with fibromyalgia. Pain Manag Nurs. 2013;14:e39–e46.

- Jamieson-Lega K, Berry R, Brown CA. Pacing: a concept analysis of a chronic pain intervention. Pain Res Manag. 2013;18:207–213.

- Lucian JV, Guallar JA, Aguado J, et al. Effectiveness of group acceptance and commitment therapy for fibromyalgia: a 6-month randomized controlled trial (EFFIGACT study). Pain. 2014;155:693–702.

- Branstetter-Rost A, Cushing C, Douleh T. Personal values and pain tolerance: does a values intervention add to acceptance? The Journal of Pain. 2009;10:887–892.

- Biguet G, Nilsson Wikmar L, Bullington J, et al. Meanings of ‘acceptance’ for patients with long-term pain when starting rehabilitation. Disabil Rehabil. 2016;38:1257–1267.

- Dragesund T, Råheim M. Norwegian psychomotor physiotherapy and patients with chronic pain: patients’ perspective on body awareness. Physiother Theory Pract. 2008;24:243–254.

- Brené B. The gifts of imperfection: let go of who you think you’re supposed to be and embrace who you are New York, USA: Hazelden; 2010.

- Lindström B, Eriksson M. Contextualizing salutogenesis and Antonovsky in public health development. Health Internat. 2006;3:238–244.

References

- Grundel A. Frigörande dans motion för kropp och själ [Freeing Dance excercise for body and soul]. Stjärnsund: Frigörande Dans Akademins Förlag; 1998.

- Grundel A. Frigörande dans i mindfulness. Vad händer egentligen? [Freeing Dance in Mindfulness. What is really happening?]. Stjärnsund: Frigörande Dans Akademin; 2016.

- Roth G. Connections: the five threads of intuitive wisdom. New York, USA: Tarcher; 2004.

Appendix

Free movement dance

The first author of this study came in contact with Freeing Dance in Mindfulness (FDiM) (http://fridans.nu/frigorande-dans/?lang=en) in 2009 and decided to participate in the education to become a FDiM guide more of a private interest than to use it as a physiotherapy group intervention. To find your own convenient movements in positions chosen by yourself in every moment and to be guided into listening to the bodies’ signals are significant in FDiM. The first author, who has been working for many years with patients with PP, found this method very interesting, and started to test the method at work with her patients. To be able to use it as a physiotherapy intervention with patients with PP she added pacing of movements, pain education, targeting kinesiophobia, body awareness practice and pain management where the patients practiced to meet the pain instead of avoiding it. The patients’ anamnesis is taken as usual and an individual examination as well when first meeting the patient with persisting pain. Hereby is the physiotherapist able to guide the patients during the group sessions to learn to avoid dysfunctional and harming movements, for example: ‘if your back hurts when you bend forwards, try to find other ways to move which are less painful’. With these adjustments the first author named the new intervention Free Movement Dance (FMD).

The patients expressed for example that they were able to cope with pain better and sometimes even felt less pain and that they became calmer and happier after participating in FMD. They also described that they became more aware of themselves and got better self-confidence. These outspoken effects of FMD inspired the first author to research FMD as a physiotherapy intervention. She decided together with the second author and the supervisor to research the intervention with qualitative content analysis by interviewing patients to understand more what was happening and what mechanisms that seemed to be activated during FMD.

History of freeing dance

FDiM was developed by Anne Grundel (Citation1,Citation2), dance guide. She was inspired by the Five Rhythms, a method designed by Gabrielle Roth (Citation3). Grundel further developed the method with two more rhythms and uses hereby seven rhythms: flowing, staccato, chaos, lightness, stillness, shaking, and your own dance. To be present and aware of body and mind is considered very important to be able to get a deeper knowledge about the body–mind complex, which, according to Grundel, leads to increased self-knowledge. The participants are at all times asked to direct their awareness inwards and to try to keep part of the attention within themselves even in pair-exercises and other more extrovert exercises. This is called ‘double attention’, to have one ear inwards and one outwards, one eye inwards and one outwards, and so on.

Anne Grundel describes the method in her book ‘Freeing Dance – motion for body and soul’ page 12 (Citation1): ‘Freeing Dance in Mindfulness is your own dance – completely your own movements. You learn to listen inwards and to move as you like right now – without demands that it should be beautiful or “right”. No learned steps, no given rhythms. You move as you like to move in the present moment and desire and form your own dance. The dance guide gives general directives, inspires to movement and leads the exercises. The guiding helps to be present in the body and mind but you decide how and in what position you would like to move different parts of your body. It can also be a meditation, a quick way to inner calmness. Just as a cyclone has its calm centre we have a place within where there is total peace and that we can come in contact with when moving the body in body–mind presence’.

Advantages mentioned in the book are that dance builds up health and vitality, provides exercise, strengthens the concentration, and increases creativity. Dance gives the pain massage from the inside and breaks the power of habit.

Description of the seven rhythms

Seven different rhythms are used in FDiM as well as in FMD. These rhythms can be used to practice being in life itself. Sometimes everything is easy going and life flows, and sometimes it is chaos and uncertain. To practice and move the body to different rhythms is also a way of practice to be in life itself. Music is chosen to inspire the different rhythms and is a main component of the guiding, for example, drums are often chosen when the rhythm ‘shaking’ is to be explored.

Some examples of the guidance to each rhythm are given below:

Flowing: to move in water, to move your inner fluids. ‘Dance like being in water, move your inner water’. ‘How does it feel when you are in flow with life itself?’

Staccato: to move towards a goal, to express your yes or your no. Decisiveness, to stand up for yourself and your rights. ‘How do you feel today? How would you like to express with your body movements to say yes or no?’

Chaos: to let go, to let go of controlling the body, to accept what is no matter what. ‘Let go of control in your neck, release your neck in a way that feels ok for you right now’

Lightness: playfulness, like being in the air, to spread the wings and fly. ‘How do your wings feel today? Small and tired or huge and powerful? Be true to yourself and fly with your wings in your own way’

Slow motion: to move slowly with full attention to the body parts and sometimes completely still. ‘Move as slow as possible and be aware of how you feel and how your body reacts on slow motions? Does it feels nice or is it provocative and stressful? Just be aware of how it feels’

Shakings: to shake and vibrate in different ways. ‘Listen to your hand, how you’re your hand wants to shake right now, and your back….’

Your own dance: the participants explore their own dance, to express how you feel in movements or even not to move, find your own rhythm and your own movement. ‘Everybody can really dance their own dance’.

Description of a group session with patients with PP

To have a group session you need a room with free space to move. The group usually consists of 8–12 patients practicing FMD during one and a half hour. The participants get a yoga mat, cushion and a blanket so that they can lie down comfortably whenever they like during the session. Some participants find it difficult to come down on the floor and use a chair to sit on instead. The session begins with a gathering, sitting in a ring to inform about something or if someone has something important to express. This is also a moment where you as a physiotherapist can explain pain or other information that is important to bring to patients with PP. It is also a quiet moment where everybody is given the possibility to calm down and to land in the room together with the others in the group. Soft music is playing in the background and in the middle of the circle you may like to place coloured silk scarves, a vase with beautiful flowers, and a lit candle. This is very much appreciated by the participants.

The dance usually begins in an upright position. To calming music we start warming up all joints and muscles in our bodies, bit by bit. We ‘lubricate’ and massage our bodies from the inside with movements. ‘Breathe and keep your attention within yourself’ is often repeated by the physiotherapist. The front, the stomach (belly), the chest, the throat and the face are mentioned, as well as inner organs which are parts of the body that easily could be forgotten. The next step could be shaking to drum music. ‘Shake and let loose. Shake in a way that feels comfortable to you’. After the warming up, we start dancing our own dance. ‘Feel how your body wants to move. Listen to your body. What feels nice right now? Discover your limits and respect them. If you need to lie down or sit for a while, keep on dancing in your own way, be it just small movements or dancing from the inside if the body hurts in a way that makes I difficult to move today’. At this point we also let different parts of the body dance with each other, that is, right hand dances with left foot or belly with chest just to be conscious of your body. Encouraging to dance with healthy parts that do not hurt at the moment. ‘Right now’ is an important part because even if the pain is felt constantly the intensity and area will change as we explore the pain closer.

Between the songs we stop and notice how it feels in the body and whether someone needs to change position, like sitting or lying down. The participants are free to change positions whenever they like. There are no rules in FMD regarding how to practice the dance or in what positions. It is simply free.

Everybody seeks a comfortable, restful position. In the rest it is possible to totally let go and even to take a short nap if needed. After a short rest, an exercise of awareness of the pain is possible. The physiotherapist guides the participants into body awareness under relaxation.

Instructions can be as follow: ‘Breathe deeply a few times and relax…… Listen to the sounds in your own body…… Be aware of your thoughts…. just observe your thoughts…. Be curious as if you experience yourself for the first time……. Is there any special part of your body that attracts attention?……… Is it a feeling, pain or something else?………… Examine this area…………. Follow the contours…………. What do they look like………………. Does it have any special form?………… Is there one colour or more in this area?…………. Is the area increasing or decreasing?…………. Does it have to do with some memory that you have?……………. If this area would express itself in words, would it like to tell you something? Listen carefully to this area……………. Breathe……… If this area would like to move or dance, what would it look like?………………… Try to find out and feel and start to express the wish of the area through your moves and your dance’.

Everybody starts expressing in dance what they experience with their eyes shut. Calm and emotional music is played, preferably not common songs with known words to avoid influence from something else but oneself. This exercise continues for about 10–20 min. Then the participants rest and try to feel what they have experienced. Pen and paper are available if someone would like to express themselves in picture, image or drawing, colours or text, just to give them a possibility to express themselves. No analysis is performed by the physiotherapist or the group, but if something has come up that is challenging or that has brought up a lot of feelings, there is always a possibility to get help or when needed to talk to the physiotherapist afterwards. No participant should be left alone if they need support!

This is often succeeded by dancing different rhythms, such as flowing, staccato, chaos, lightness or stillness to music suiting these rhythms. There is always a possibility to rest whenever needed but it is recommended to try to move those parts that the body can manage, if only the little finger.

The group session ends by all participants sitting together in a circle to share experiences. In this way, everybody has a possibility to express what feels important right now, in this moment. A ‘talking stone’ is passed around and when holding this stone in the hand it is possible to express how you feel or to be silent for a while, just having your own time and space with full attention from the others in the group, listening carefully to what is being said or just being in silence together. It is of great importance that what is being said in the circle, stays in the circle. The participants can talk about their own experiences with others outside the group, but not about things that have been expressed by the other participants in the group during the sessions. This is a code of honour. Most participants claim that sharing is an important part of the treatment. One patient said: ‘It is so good to hear somebody else saying exactly what I feel. It makes me feel less alone and strange’.

The sharing and verbalising part also gives the opportunity for the physiotherapist to answer questions from the group members and also to give lectures in pain education for example.

The sessions are not always following the same pattern. As the guiding physiotherapist, you need to use your intuition and your presence to feel the participants and their different needs in the moment. You can have an idea of what you will bring to the group, but very often you have to change both music and exercises. Sometimes the participants are tired and have a lot of pain, in other sessions there can be a lot of energy in the room so you as a guide have to adapt to the group and to their present mood. This is often the case in physiotherapy practice anyway to work more intuitively and trust yourself as a leader.