Abstract

Background

Multiple Sclerosis (MS) is an incurable neuroinflammatory disease of the central nervous system that affects more than 2.2 million people globally. Although evidence shows the benefits of physical activity and exercise, participation in exercise in people with Multiple Sclerosis (pwMS) has been poor. A synthesis of qualitative research is required to better understand the factors associated with physical activity and exercise participation in pwMS.

Objectives

To synthesise findings from qualitative studies exploring factors associated with physical activity and exercise participation in people with MS.

Methodology

Qualitative systematic review using the Inductive Thematic Synthesis approach.

Data sources

CINAHL, Embase, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, and Scopus databases were systematically searched with further searches of reference lists and OpenGrey.

Study eligibility criteria

Qualitative studies or mixed-method studies with relevant qualitative content that explored the factors related to physical activity and exercise participation in people with MS.

Study synthesis and appraisal

Thematic Synthesis and Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) qualitative studies checklist.

Results

Thirty-nine studies met the inclusion criteria. Three analytical themes were generated from 11 descriptive themes outlining the factors associated with physical activity and exercise participation in people with MS.

Conclusion

Physical activity and exercise participation in people with MS is influenced by internal and external factors. PwMS adopt a range of strategies to sustain physical activity and exercise participation. Healthcare professionals could play a role in the physical activity and exercise participation of pwMS.

Systematic Review Registration Number

PROSPERO 2020:CRD42020214002.

Introduction

Multiple Sclerosis (MS) is a progressive neurological condition that affects more than 2.2 million people globally [Citation1]. Exercise is considered as an intervention for improving muscle strength, fitness, fatigue, and health-related quality of life of people with MS (pwMS) [Citation2–4]. But there is limited evidence on the most effective form of exercise for pwMS [Citation5,Citation6]. Despite the widely reported benefits, physical activity (PA) and exercise levels in pwMS are considerably low [Citation7,Citation8]. Understanding of the influencing factors will help healthcare professionals to implement strategies that could improve PA and exercise participation in pwMS. But there are only two qualitative systematic reviews that synthesised the perceptions of PA and exercise in pwMS, and both were published in 2016 [Citation9,Citation10]. There is a value in conducting an updated qualitative systematic review in this area as it will include recent research that helps us to identify and expand our knowledge on the contemporary factors. The aim of this systematic review is to systematically synthesise findings from qualitative studies exploring factors associated with PA and exercise participation in people with Multiple Sclerosis. Research questions: What are the barriers and facilitators to PA and exercise participation in pwMS? How do these factors influence their PA and exercise participation?

Methodology

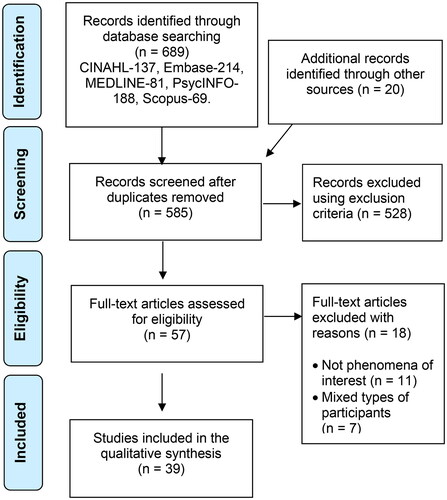

A qualitative systematic review using the Inductive Thematic Synthesis approach was implemented for the synthesis of qualitative data. The inductive approach was used for coding, concept translation, and interpretation of data [Citation11]. Constant comparison was integrated throughout the synthesis to assess the transferability of themes between studies [Citation12]. The enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research (ENTREQ) framework was used to enhance rigour [Citation13]. PRISMA flowchart was used for reporting the study selection [Citation14]. A protocol was registered on the PROSPERO database (PROSPERO 2020: CRD42020214002).

Methods

Definitions

Physical activity is any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that requires energy expenditure [Citation15]. Exercise is considered as a component of physical activity; however, some claim there is little difference between them [Citation16]. Physical activity and exercise may be in any kind of form, such as aerobic training, resistance training, balance training, or in specific types, such as yoga, swimming, and Tai-chi. Activities of daily living were not considered as PA for the purpose of this review. Within the literature on this topic, the terms PA and exercise are being used interchangeably. Therefore, in this review, the terms PA and exercise were used jointly and interchangeably. PA and exercise participation were considered as involvement in them independently or following the advice of healthcare professionals.

Search strategy

An information specialist was consulted to ensure the search strategy was rigorous. A systematic search was completed by CC between September and October 2020, and updated again in February 2023 using databases: CINAHL, Embase, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, and Scopus. The literature search was a three-step process. First, an initial search was started in MEDLINE with keywords including ‘Multiple Sclerosis’, ‘exercise’, ‘factors’, and ‘qualitative’. Common synonyms or abbreviations, such as ‘MS’, ‘physical activity’, ‘barriers’, ‘facilitators’, ‘interview’, and ‘focus group’ were included. The search result was then analysed to examine if most synonyms and spelling variations of the keywords were covered. This search strategy was then used as a grounding syntax for advanced searching in other databases. Second, the search was undertaken across all listed databases with specific controlled vocabularies and full-text terms, combined with Boolean operators to optimise the search results. Full-text terms were restricted to titles, abstracts, and keywords. Third, the reference lists of the included studies were hand-searched by CC for additional studies. The search was limited to studies published between 1 January 2000 and 19 February 2023. Grey literature was searched in OpenGrey. Endnote X9.3.3 was used as a citation manager throughout the screening process, and Microsoft Excel 16.48 was used for documentation. Once the search strategy was compiled, a citation list of the results was extracted and imported to Endnote. Duplicate items were removed before screening the titles and abstracts. CC screened the titles and abstracts to identify relevant studies that met the inclusion criteria for full-text screening. Then, CC and KG independently screened full-text articles and were blinded to each other’s decision. The decision to include studies in thematic synthesis was only made once the full-text screening was completed by both authors, discussed, and resolved any discrepancies that arose.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion: Qualitative studies and qualitative content in mixed-method studies which explored factors related to PA and exercise and recruited people aged over 18 years old, diagnosed with any type of MS, and from any country of origin. Exclusion: Studies that did not report data on the phenomena of interest, quantitative studies, conference abstracts, reviews, experts’ opinions, and studies not written in English.

Quality assessment

The quality of studies was assessed by both reviewers using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme qualitative checklist [Citation17]. Reviewers were blinded to each other’s evaluation and disagreements were deliberated until a consensus was reached. No limits were applied to the quality of the studies.

Data extraction and synthesis

Participant characteristics, contextual and methodological information were extracted (). Participants’ quotations and authors’ explanations were extracted and used in the data synthesis. Thematic synthesis was implemented in three stages: coding, developing descriptive themes, and generating analytical themes [Citation11]. CC completed line by line coding of all the included studies. KG also performed line by line coding of 50% of the included studies. Both reviewers compared and discussed their codes for quality assurance. CC developed descriptive themes and generated analytical themes. KG made recommendations throughout. Synthesis continued until all analytical themes were sufficiently abstract to cover all the descriptive themes and answered the review questions.

Table 1. Characteristics of the included studies.

Results

Study selection

A total of 689 records were identified. After eliminating the duplicates and exclusions, 39 [Citation18–56] studies involving 726 pwMS (71.5% Female, 21.6% Male, 6.9% unreported) with age distribution: young adults (<39 years) 8.3%, middle aged adults (40–59) 25.3%, older adults (>60) 9.8%, unreported 56.6% were included [Citation18–56]. The number of studies and the % of participants according to the country were: three Australia (6%), five Canada (13.3%), two Ireland (4.3%), seven UK (18%), 17 USA (49.1%), five New Zealand (9.3%). The type of MS distribution was, RR 46.3%, SP 11.3%, PP 6%, PR 3%, CP and Benign 0.4% each, and 33% unreported. The level of disability based on EDSS were mild 2.1%, moderate 6.3%, mild to moderate 6.9%, severe 0.8%, and unreported 83.9%. Details of the study selection process are shown in the PRISMA flowchart (). The characteristics of the included studies are presented in .

Quality of the included studies

The methodological quality of the included studies was assessed by giving a score (0 = No; 0.5 = Can’t Tell; 1 = Yes) for responses on the CASP tool [Citation57]. All included studies addressed nine out of the 10 items on the CASP tool and were considered as high quality (). Only 11 out of the 39 studies reported the relationship between researchers and participants.

Table 2. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) qualitative studies checklist.

Themes

Three analytical themes emerged from 11 descriptive themes outlining the factors associated with physical activity and exercise participation in PwMS, with each analytical theme consisting of two or more descriptive themes ().

Table 3. Main findings of the thematic synthesis.

Descriptive themes

(1a) Environment

Physical activity and exercise environments were cited as a factor in 16 studies [Citation20–24,Citation32,Citation34–36,Citation38,Citation40,Citation41,Citation43,Citation44,Citation51,Citation52]. The hot environment was described as a barrier because the heat exacerbated fatigue and MS symptoms [Citation20,Citation22,Citation24,Citation32,Citation35,Citation36,Citation38,Citation40,Citation41,Citation43,Citation44]. The perceived safety of the environment affected willingness to exercise [Citation20–22,Citation24,Citation32,Citation34,Citation35,Citation40,Citation41,Citation51,Citation52]. Staff assistants and knowledgeable instructors at the exercise facilities were regarded as facilitators. During the COVID-19 pandemic, although fear of exposure to the virus became a barrier to participation, virtual activity environments, such as online classes were reported as facilitators.

(1b) Accessibility

Participants in 27 studies regarded accessibility issues as barriers to PA and exercise [Citation19–22,Citation24–27,Citation29,Citation31–38,Citation40,Citation41,Citation44–47,Citation49,Citation51,Citation52,Citation54]. Barriers included accessibility to the facility [Citation20,Citation22,Citation32,Citation33,Citation36,Citation38,Citation40,Citation45–47,Citation51,Citation52,Citation54], accessibility within the facility [Citation19–22,Citation24,Citation25,Citation29,Citation33–36,Citation38,Citation40,Citation44], cost and time available [Citation19,Citation20,Citation22,Citation26,Citation27,Citation29,Citation31,Citation32,Citation35,Citation37,Citation40,Citation41,Citation44–46,Citation49,Citation54]. Social distancing measures and restrictions implemented during the COVID-19 pandemic acted as barriers to accessing facilities. Some participants had to travel long distances, which was exhausting for them. Limited accessible parking was another common constraint mentioned in the studies. Participants thought there should be more accessible facilities, such as toilets, changing rooms, showers, assisted gym, and pool. Bad weather was cited as a safety concern.

(1c) Social factors

Interactions with others that influenced PA and exercise participation were considered as social factors. These included social influence, social support, social obligation, and social stigma. 35 studies reported the impact of social factors on PA and exercise participation [Citation19–29,Citation31–42,Citation44–54,Citation56]. Most of these factors were reported as motivators for being physically active but some were considered as barriers. Participants highlighted the positive influence of exercising with other pwMS [Citation19,Citation22–27,Citation29,Citation31–35,Citation37,Citation38,Citation41,Citation47,Citation48,Citation52–54]. PwMS joined the exercise programme as a social activity to interact with others. However, participants experienced embarrassment, social stigma, and judgement from others which demotivated them [Citation19,Citation21,Citation26,Citation31–33,Citation38,Citation46,Citation49,Citation54,Citation56]. Social support from family and friends was highly valued and reported as a facilitator [Citation24–26,Citation29,Citation31,Citation32,Citation34,Citation36,Citation37,Citation39,Citation41,Citation42,Citation44,Citation45,Citation51,Citation53,Citation56], yet sometimes family and friends failed to understand the limitations and meaning of exercise to pwMS [Citation36,Citation41,Citation46]. Social obligations, such as working and caring responsibilities were mentioned as barriers [Citation36,Citation37,Citation45].

(2a) Impact of MS

Participants in 27 studies reported MS symptoms as internal barriers to PA and exercise [Citation18–22,Citation24,Citation26,Citation30,Citation32–38,Citation40,Citation41,Citation43–45,Citation47,Citation49,Citation51,Citation53–56]. Among all MS symptoms, fatigue was the most reported barrier [Citation19–22,Citation24,Citation26,Citation30,Citation32,Citation35,Citation37,Citation38,Citation40,Citation41,Citation43–45,Citation49,Citation54–56]. Other MS symptoms that inhibited PA and exercise were heat sensitivity, mobility impairments, cognitive impairments, pain, anxiety, and depression. Exacerbations, relapses, variability in MS symptoms, and functional decline were also perceived as barriers [Citation20,Citation21,Citation24,Citation30,Citation32,Citation41,Citation44,Citation45,Citation56].

(2b) Belief

Participants in 21 studies held different beliefs about PA and exercise [Citation18–20,Citation22,Citation24,Citation26,Citation27,Citation30–34,Citation37,Citation38,Citation40,Citation41,Citation44–46,Citation49,Citation55]. Positive beliefs, such as exercise is beneficial, improves MS symptoms, essential for long-term health acted as motivators to maintain an active lifestyle [Citation18,Citation19,Citation22,Citation24,Citation26,Citation27,Citation31,Citation32,Citation34,Citation36,Citation38,Citation40,Citation41,Citation44–46,Citation49,Citation55]. In contrast, some believed exercise would negatively affect their body and worsen symptoms [Citation20,Citation32,Citation36,Citation37,Citation49]. Opinions about post-exertional fatigue varied; some believed it was ‘healthy tiredness’ while others thought it was problematic [Citation27,Citation33,Citation34,Citation41].

(2c) Knowledge

Individual’s awareness and understanding of their MS, PA, and exercise were considered as knowledge. Eighteen studies reported participants’ perspective on their knowledge specific to MS, PA, and exercise [Citation18–20,Citation25,Citation26,Citation28,Citation32,Citation33,Citation35,Citation37,Citation40,Citation41,Citation43,Citation44,Citation46–48,Citation51]. When active participants were compared with those inactive, knowledge influenced engagement in regular exercise [Citation25,Citation26,Citation28,Citation40]. Active participants stayed active by balancing their rest and exercise and choosing the appropriate exercise mode linked to their physical capabilities. In general, studies highlighted patient education as an important factor to help them exercise safely and regularly [Citation19,Citation20,Citation35,Citation37,Citation40,Citation41,Citation44].

(2d) Self-efficacy

Person’s belief in their ability to perform activities was considered as self-efficacy. Regardless of physical abilities, participants in 22 studies expressed various degrees of self-efficacy in performing PA and exercise and the level of this influenced their participation [Citation18,Citation19,Citation21,Citation24–32,Citation35–40,Citation49,Citation53,Citation55,Citation56]. Participants with high self-efficacy expressed self-confidence in their physical capabilities to exercise. This perceived confidence was not only rooted in their own beliefs but also established by their past successful experience. Participants with low self-efficacy expressed fear of exercise due to their MS. Fear included fear of falling, safety, worsening symptoms, and embarrassment in front of others. Previous failed experiences also contributed to their fear.

(2e) Motivations

Participants in 37 studies described how motivation influenced their PA and exercise behaviour [Citation18–20,Citation22–35,Citation37–56]. Perceived physical and emotional benefits of PA and exercise were the main motivators. Physical benefits included symptom improvement, reduction in fatigue, improved walking, as well as better strength and balance. Exercise also generated positive feelings. Participants gained enjoyment, a sense of accomplishment, a sense of feeling better, increased confidence, better control of MS, and mindfulness from exercise. All these benefits drove continued engagement in exercise. Another source of motivation cited by participants was a commitment, which could be self-commitment to exercise, commitment to dogs, classmates, and physiotherapists. In contrast, some participants found a lack of motivation because they did not enjoy or bother [Citation19,Citation20,Citation25,Citation29,Citation37,Citation40,Citation41,Citation49,Citation52]. Some participants were frustrated and demotivated when they were unable to obtain immediate, obvious benefits, or when they compared their pre- and post-MS capabilities [Citation26,Citation30,Citation32,Citation35,Citation36,Citation41,Citation46,Citation49,Citation50]. Participants also indicated that the impact of MS on their identity motivated them in engaging in exercise to redefine themselves [Citation18,Citation21,Citation25,Citation26,Citation28,Citation30,Citation39,Citation41,Citation43,Citation45]. Having an expected outcome was indicated as a facilitator to PA and exercise in 23 studies [Citation18,Citation22–26,Citation28,Citation30,Citation31,Citation34,Citation36,Citation38–45,Citation47,Citation49,Citation51,Citation53]. Participants perceived exercise as a means for achieving specific goals. The most reported outcome was to control MS. Participants wished exercise would help control their disease progression and alleviate their symptoms. Other expectations were improving or retaining their physical capabilities, maintaining good health, sustaining independence, and improving quality of life.

(3a) Self-management

Actions implemented by pwMS to help them participate in PA and exercise were considered as self-management strategies. Twenty-two studies reported self-management strategies used by participants to maintain their PA and exercise engagement [Citation19,Citation20,Citation24–26,Citation28,Citation31–37,Citation40–44,Citation46,Citation49,Citation52,Citation56]. Participants found both intangible and tangible ways to adapt to regular exercise. Intangible strategies adopted by the participants featured components of pacing, planning, and prioritising [Citation20,Citation24,Citation26,Citation28,Citation32,Citation35,Citation37,Citation42,Citation43]. The formation of an exercise habit was also discussed [Citation20,Citation24,Citation26,Citation33,Citation42–44]. Participants integrated exercise into their lifestyle and made exercise part of their weekly routine. Pertaining to tangible strategies, self-monitoring tools were the most reported [Citation19,Citation20,Citation24,Citation26,Citation31,Citation36,Citation37,Citation42]. PwMS used wearable activity trackers, such as Fitbit, pedometer, mobile app, and exercise log to monitor their activity level. Participants made adaptations to maximise their PA and exercise engagement [Citation26,Citation33,Citation34,Citation36,Citation41,Citation43].

(3b) Professional support

PA and exercise promotion by healthcare providers was valued by participants as a facilitator for exercise engagement [Citation18,Citation34,Citation38,Citation41,Citation42,Citation47–49,Citation56]. Lack of professional advice and support were described as barriers [Citation25,Citation27,Citation32–35,Citation38,Citation39,Citation41,Citation44,Citation49]. Participants thought the advice and support specific to PA and exercise from clinicians were lacking [Citation25,Citation33,Citation34,Citation38,Citation39,Citation41,Citation44]. They hoped clinicians could provide MS specific advice on what they could do to help themselves. PwMS also highlighted the need for PA and exercise prescription and guidance tailored to MS by healthcare professionals [Citation25,Citation27,Citation32–35,Citation44].

(3c) Interventions

Studies explored participants’ view of exercise after completing an intervention programme [Citation20,Citation25,Citation27,Citation29,Citation31,Citation33,Citation36,Citation37,Citation42,Citation47,Citation50,Citation52–54]. A tailored supervised exercise programme, in either an individual or a group setting with pwMS was carried out in some studies [Citation25,Citation27,Citation29,Citation31,Citation33,Citation36,Citation48,Citation53,Citation54]. Participants expressed that they learned a lot from the programme. Participants also realised they were capable of ‘doing something’ even when they were limited by MS. Furthermore, participants valued sharing and learning from others with MS because peers can understand their difficulties better.

Analytical themes

(1) External factors affect physical activity and exercise participation

External factors, such as poor weather, heat, perceived safety, cost, travel time, and problems with accessibility act as barriers to physical activity and exercise participation in pwMS. While restrictions during the pandemic act as barriers, online classes act as facilitators. Although staff assistance and knowledgeable instructors act as facilitators, the majority of external factors related to the environment were considered as barriers. People with MS feel safer when they exercise in a quiet, less crowded, convenient, and disabled-friendly environment. Positive social influence and support are highly valued and regarded as facilitators. These play an important role in maintaining PA and exercise participation. While most social factors are enablers, some factors, such as social obligations and stigma act as inhibitors for PA and exercise participation. PwMS feel a sense of belonging, companionship, acceptance, and encouragement when surrounded by other pwMS. These feelings motivate them to engage in the PA and exercise programmes.

(2) Internal factors alter physical activity and exercise behaviour

The impact of MS, in particular, fatigue acts as a barrier in PA and exercise engagement. Active participants are more confident, motivated, and positive about taking part in PA and exercise compared to inactive individuals. PwMS demonstrate mixed beliefs and understanding of PA and exercise. Their beliefs and knowledge exert influence on exercise behaviour. People who believe PA and exercise is important and beneficial to their health exercise regularly and demonstrate more knowledge specific to PA and exercise. Higher levels of self-efficacy act as facilitator for participation in PA and exercise. Perceived benefits, positive experiences, and expectations act as motivators for PA and exercise participation in pwMS.

(3) Self-management, professional support, and interventions are beneficial

PwMS adopt various self-management strategies to support participation in PA and exercise. PwMS use pacing, planning, prioritising, and making adaptations to integrate PA and exercise into their life. PwMS learn new strategies from participating in exercise programmes with other pwMS and attending exercise promotion activities by healthcare professionals. Professional support and advice are helpful in facilitating PA and exercise participation in pwMS. However, professionals’ input is either lacking or insufficient. In addition to PA and exercise promotion, more professional support and advice are required to encourage pwMS to exercise. Interventions, such as tailored exercise programmes are valued and helpful for better engagement in PA and exercise over time.

Discussion

This review generated three new analytical themes that offered an improved understanding of the factors associated with PA and exercise participation in pwMS.

(1) External factors affect physical activity and exercise participation

PA and exercise participation in pwMS is influenced by external factors, such as environment, accessibility, and social factors. The majority of environmental factors found in this review were identified as barriers to PA and exercise participation. Though this finding was similar to Christensen et al.’s review [Citation9], it was different from Learmonth and Motl’s review [Citation10] which reported many as facilitators. The differences could be explained by the method of synthesis implemented in this review. Besides the similarities, this review found COVID-19 pandemic restrictions and fear of exposure to the virus acted as barriers. Although some of the aspects of social influence were considered as barriers in Learmonth and Motl’s review [Citation10], social support and social influence were found as facilitators in the current review. Additionally, this review found social stigma, and social obligations as barriers. While participating in MS-specific group exercise setting, pwMS are not embarrassed about their MS related problems. Disease specific exercise settings make pwMS feel safe, comfortable, and confident which motivates them to participate in exercise. Although many studies reported accessibility issues to facilities acted as barriers, the online exercise classes acted as facilitators. While planning exercise facilities, providers could consider the issues around accessibility, safety, and comfort of the environment. Professionals could consider organising disease specific group, and online exercise classes for pwMS.

(2) Internal factors alter physical activity and exercise behaviour

MS related symptoms and the impact of MS were found as barriers to PA and exercise participation. Fatigue is deemed as the most influential barrier to PA and exercise. Therefore, when promoting PA and exercise to pwMS, healthcare professionals should discuss fatigue related impediments and deliver appropriate advice to help them gain control over their fatigue. In addition to the barriers reported in the previous reviews [Citation9,Citation10], this review found heat sensitivity, and functional decline as the barriers. The findings of this review indicated that personal beliefs and knowledge altered PA and exercise behaviour. While positive beliefs facilitated participation, negative beliefs and lack of knowledge acted as barriers. This review found that personal motivation influences PA and exercise behaviour of pwMS. Perceived benefits, previous positive experiences, and expected outcomes act as motivators for PA and exercise participation. Although the motivating factors found in this review were also reported in the previous reviews [Citation9,Citation10], impact of MS on identity, lack of enjoyment and not seeing immediate benefits were found to impact motivation. This review found that the level of self-efficacy influences the PA and exercise behaviour of pwMS. High self-efficacy facilitates PA and exercise participation in pwMS, and low self-efficacy acts as a barrier. Several studies highlighted that mastery experience contributed to higher self-efficacy in pwMS [Citation23,Citation27–29,Citation31,Citation33]. Mastery experience could come from a past successful exercise experience and develop from joining an exercise programme. Healthcare professionals could design programmes that fit with the capabilities, interests of pwMS and enhances their mastery experience.

(3) Self-management, professional support, and interventions are beneficial

PwMS adopt a range of strategies to sustain PA and exercise participation. PwMS apply energy conservation strategies to manage their fatigue so that they could manage day to day activities more efficiently and retain energy for PA and exercise. This review synthesised tangible and intangible strategies. Wearable activity trackers found in this review were contemporary to the strategies reported in the previous review [Citation9]. Advice and promotion by healthcare professionals appear to be important in facilitating knowledge and positive beliefs. Similarly, a review by Learmonth and Motl [Citation10] suggested that limited advice from healthcare professionals acted as a barrier. Professional’s knowledge, support, and advice were mentioned in the previous reviews as determinants of PA and exercise participation in pwMS [Citation9,Citation10], the findings of this review concurred that information from healthcare professionals was either lacking or inconsistent. Healthcare professionals should consider providing MS specific advice and deliver tailored materials addressing the needs of pwMS.

Strengths and limitations

The review expanded our knowledge of the factors associated with PA and exercise participation in pwMS. The findings of this review synthesised three new analytical themes, reinforced existing knowledge, and enhanced our knowledge of the factors, such as COVID-19 restrictions, social stigma, social obligation, online classes, wearable technologies, enjoyment, impact on identity, and lack of immediate benefits. Methods were implemented to ensure rigour and transparency. Some of the stages were completed by only one researcher. The findings are mainly dominated by the views of women with RRMS living in English speaking developed countries. The age groups, level of activity, and disability level of MS were not well-reported in the studies. This qualitative review could not explore the effects of participant characteristics, type, volume, intensity, frequency, duration, and level of activities on PA and exercise participation. In the literature, the terms physical activity and exercise were used interchangeably, therefore it was not possible to distinguish the differences between them.

Conclusion

External and internal factors influence the physical activity and exercise participation of pwMS. PwMS adopt a range of strategies to sustain PA and exercise participation. Healthcare professionals could play a role in the physical activity and exercise participation of pwMS by initiating and reinforcing the facilitating factors and advising and offering support on the barriers.

Acknowledgements

This work was submitted by Chung Tak Chan as a Dissertation in partial fulfillment of the course MSc Physiotherapy (Pre-registration) at the University of Brighton.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Wallin MT, Culpepper WJ, Nichols E, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of multiple sclerosis 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18(3):269–285.

- Pilutti LA, Greenlee TA, Motl RW, et al. Effects of exercise training on fatigue in multiple sclerosis. Psychosom Med. 2013;75(6):575–580.

- Latimer-Cheung AE, Pilutti LA, Hicks AL, et al. Effects of exercise training on fitness, mobility, fatigue, and health-related quality of life among adults with multiple sclerosis: a systematic review to inform guideline development. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;94(9):1800–1828.e3.

- Platta ME, Ensari I, Motl RW, et al. Effect of exercise training on fitness in multiple sclerosis: a meta-analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2016;97(9):1564–1572.

- Edwards T, Pilutti LA. The effect of exercise training in adults with multiple sclerosis with severe mobility disability: a systematic review and future research directions. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2017;16:31–39.

- Dalgas U, Langeskov-Christensen M, Stenager E, et al. Exercise as medicine in multiple sclerosis—time for a paradigm shift: preventive, symptomatic, and disease-modifying aspects and perspectives. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2019;19(11):1–12.

- Motl RW, McAuley E, Snook EM. Physical activity and multiple sclerosis: a meta-analysis. Mult Scler. 2005;11(4):459–463.

- Kinnett-Hopkins D, Adamson B, Rougeau K, et al. People with MS are less physically active than healthy controls but as active as those with other chronic diseases: an updated meta-analysis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2017;13:38–43.

- Christensen ME, Brincks J, Schnieber A, et al. The intention to exercise and the execution of exercise among persons with multiple sclerosis–a qualitative metasynthesis. Disabil Rehabil. 2016;38(11):1023–1033.

- Learmonth YC, Motl RW. Physical activity and exercise training in multiple sclerosis: a review and content analysis of qualitative research identifying perceived determinants and consequences. Disabil Rehabil. 2016;38(13):1227–1242.

- Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8(1):1–10.

- Barnett-Page E, Thomas J. Methods for the synthesis of qualitative research: a critical review. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2009;9(1):1–11.

- Tong A, Flemming K, McInnes E, et al. Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012;12(1):1–8.

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLOS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097.

- World Health Organization. Physical activity; 2022. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/physical-activity

- Winter EM, Fowler N. Exercise defined and quantified according to the Systeme International d‘Unites. J Sports Sci. 2009;27(5):447–460.

- CASP Qualitative Checklist; 2018. Available from: https://casp-uk.b-cdn.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-2018_fillable_form.pdf

- Adamson BC, Adamson MD, Littlefield MM, et al. Move it or lose it”: perceptions of the impact of physical activity on multiple sclerosis symptoms, relapse and disability identity. Qualitative research in sport, exercise and health [internet]. Informa UK Limited. 2017;10(4):457–475.

- Aminian S, Ezeugwu VE, Motl RW, et al. Sit less and move more: perspectives of adults with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2019;41(8):904–911.

- Barnard E, Brown CR, Weiland TJ, et al. Understanding barriers, enablers, and long-term adherence to a health behavior intervention in people with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2020;42(6):822–832.

- Borkoles E, Nicholls AR, Bell K, et al. The lived experiences of people diagnosed with multiple sclerosis in relation to exercise. Psychol Health. 2008;23(4):427–441.

- Brown C, Kitchen K, Nicoll K. Barriers and facilitators related to participation in aquafitness programs for people with multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2012;14(3):132–141.

- Chard S. Qualitative perspectives on aquatic exercise initiation and satisfaction among persons with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2017;39(13):1307–1312.

- Chiu C-Y, Bezyak J, Griffith D, et al. Psychosocial factors influencing lifestyle physical activity engagement of African Americans with multiple sclerosis: a qualitative study. J Rehabil. 2016;82(2):25–30. Available from: https://www.proquest.com/docview/1806222015/77B17096C02D4F7DPQ/6?accountid=9727

- Crank H, Carter A, Humphreys L, et al. Qualitative investigation of exercise perceptions and experiences in people with multiple sclerosis before, during, and after participation in a personally tailored exercise program. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;98(12):2520–2525.

- Dlugonski D, Joyce RJ, Motl RW. Meanings, motivations, and strategies for engaging in physical activity among women with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34(25):2148–2157.

- Dodd KJ, Taylor NF, Denisenko S, et al. A qualitative analysis of a progressive resistance exercise programme for people with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2006;28(18):1127–1134.

- Fasczewski KS, Gill DL, Rothberger SM. Physical activity motivation and benefits in people with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2018;40(13):1517–1523.

- Giacobbi PR, Dietrich F, Larson R, et al. Exercise and quality of life in women with multiple sclerosis. Adapt Phys Activ Q. 2012;29(3):224–242.

- Hall-McMaster SM, Treharne GJ, Smith CM. “The positive feel”: unpacking the role of positive thinking in people with multiple sclerosis’s thinking aloud about staying physically active. J Health Psychol. 2016;21(12):3026–3036.

- Kasser S. Exercising with multiple sclerosis: insights into meaning and motivation. Adapt Phys Activ Q. 2009;26(3):274–289.

- Kayes NM, McPherson KM, Taylor D, et al. Facilitators and barriers to engagement in physical activity for people with multiple sclerosis: a qualitative investigation. Disabil Rehabil. 2011;33(8):625–642.

- Learmonth YC, Marshall-McKenna R, Paul L, et al. A qualitative exploration of the impact of a 12-week group exercise class for those moderately affected with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2013;35(1):81–88.

- Learmonth YC, Rice IM, Ostler T, et al. Perspectives on physical activity among people with multiple sclerosis who are wheelchair users. Int J MS Care. 2015;17(3):109–119.

- Moffat F, Paul L. Barriers and solutions to participation in exercise for moderately disabled people with multiple sclerosis not currently exercising: a consensus development study using nominal group technique. Disabil Rehabil. 2019;41(23):2775–2783.

- Plow MA, Resnik L, Allen SM. Exploring physical activity behaviour of persons with multiple sclerosis: a qualitative pilot study. Disabil Rehabil. 2009;31(20):1652–1665.

- Plow M, Bethoux F, Mai K, et al. A formative evaluation of customized pamphlets to promote physical activity and symptom self-management in women with multiple sclerosis. Health Educ Res. 2014;29(5):883–896.

- Richardson EV, Barstow E, Motl RW. Exercise experiences among persons with multiple sclerosis living in the southeast of the United States. Disabil Rehabil. 2022;44(1):79–87.

- Schneider M, Young N. “So this is my new life”: a qualitative examination of women living with multiple sclerosis and the coping strategies they use when accessing physical activity. DSQ. 2010;30(3/4):1–8.

- Silveira SL, Richardson EV, Motl RW. Social cognitive theory as a guide for exercise engagement in persons with multiple sclerosis who use wheelchairs for mobility. Health Educ Res. 2020;35(4):270–282.

- Smith C, Olson K, Hale LA, et al. How does fatigue influence community-based exercise participation in people with multiple sclerosis? Disabil Rehabil. 2011;33(23–24):2362–2371.

- Smith CM, Hale LA, Mulligan HF, et al. Participant perceptions of a novel physiotherapy approach (“blue prescription”) for increasing levels of physical activity in people with multiple sclerosis: a qualitative study following intervention. Disabil Rehabil. 2013;35(14):1174–1181.

- Smith CM, M, Fitzgerald HJ, Whitehead L. How fatigue influences exercise participation in men with multiple sclerosis. Qual Health Res. 2015;25(2):179–188.

- Smith M, Neibling B, Williams G, et al. A qualitative study of active participation in sport and exercise for individuals with multiple sclerosis. Physiother Res Int. 2019;24(3):e1776.

- Stennett A, De Souza L, Norris M. The meaning of exercise and physical activity in community dwelling people with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2020;42(3):317–323.

- Adamson B, Kinnett-Hopkins D, Athari Anaraki N, et al. The experiences of inaccessibility and ableism related to physical activity: a photo elicitation study among individuals with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2022;44(12):2648–2659.

- Akbar N, Hazlewood S, Clement M, et al. Experiences and perceived outcomes of persons with multiple sclerosis from participating in a randomized controlled trial testing implementation of the Canadian physical activity guidelines for adults with MS: an embedded qualitative study. Disabil Rehabil. 2022;44(17):4663–4671.

- Clarke R, Coote S. Perceptions of participants in a group, community, exercise programme for people with multiple sclerosis. Rehabil Res Pract. 2015;2015:123494.

- Fifolt M, Richardson EV, Barstow E, et al. Exercise behaviors of persons with multiple sclerosis through the stepwise implementation lens of social cognitive theory. Disabil Rehabil. 2020;42(7):948–956.

- Kim Y, Mehta T, Tracy T, et al. A qualitative evaluation of a clinic versus home exercise rehabilitation program for adults with multiple sclerosis: the tele-exercise and multiple sclerosis (TEAMS) study. Disabil Health J. 2022:101437. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2022.101437

- Koopmans A, Pelletier C. Physical activity experiences of people with multiple sclerosis during the COVID-19 pandemic. Disabilities. 2022;2(1):41–55.

- Palmer LC, Neal WN, Motl RW, et al. The impact of COVID-19 lockdown restrictions on exercise behavior among people with multiple sclerosis enrolled in an exercise trial: qualitative interview study. JMIR Rehabil Assist Technol. 2022;9(4):e42157.

- Russell N, Gallagher S, Msetfi RM, et al. Experiences of people with multiple sclerosis participating in a social cognitive behavior change physical activity intervention. Physiother Theory Pract. 2023;39(5):954–962.

- van der Linden ML, Bulley C, Geneen LJ, et al. Pilates for people with multiple sclerosis who use a wheelchair: feasibility, efficacy and participant experiences. Disabil Rehabil. 2014;36(11):932–939.

- Ware M, O'Connor P, Bub K, et al. The role of worry in exercise and physical activity behavior of people with multiple sclerosis. Health Psychol Behav Med. 2022;10(1):786–805.

- Wilkinson H, McGraw C, Chung K, et al. “Can I exercise? Would it help? Would it not?”: exploring the experiences of people with relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis engaging with physical activity during a relapse: a qualitative study. Disabil Rehabil. 2022:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2022.2084774

- Butler A, Hall H, Copnell B. A guide to writing a qualitative systematic review protocol to enhance evidence-based practice in nursing and health care. Worldv Evid-Based Nurs. 2016;13(3):241–249.