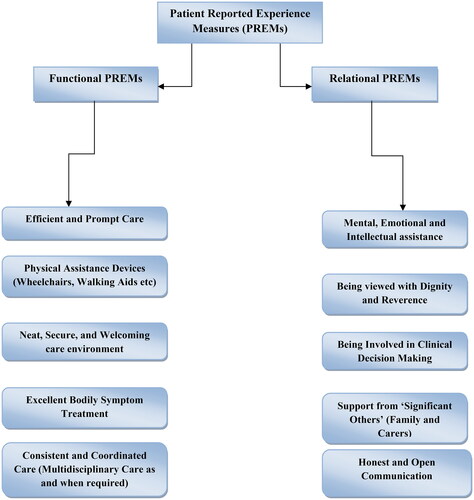

The perfect patient experience can be achieved by satisfying four fundamental human needs: Self-assurance, integrity, pride and enthusiasm [Citation1]. Patient experience is defined as ‘view of patient’ on what happened in the process of receiving treatment, including the objective facts and their subjective perceptions [Citation1]. Clinical efficacy, safety and patient experience are three pillars of National Health Service (NHS) framework for holistic patient management [Citation1]. Patient-reported experience measures (PREMs) have gained prominence to monitor the quality of care in all three domains [Citation1]. The NHS outlines eight domains, which formulate a ‘good’ patient experience, which are dignity, expertise, interpersonal interaction, physical ease, emotional assistance and access to care [Citation1]. PREMs facilitate information from patients about their experiences while obtaining care [Citation1,Citation2]. PREMs can be of two types: relational or functional () [Citation1,Citation2].

Patient-reported experiences provide information on the patient-centeredness and it is considered a reliable quality of care parameter [Citation2]. Patient-reported experience focuses on present situation of health care services and explores the domains for future developments [Citation2]. PREMs have recently been utilised to inform performance-based compensation, strategies for benchmarking, effectiveness, health information technology and resource usage [Citation2]. On the other hand, PREMs are a standard that has been critiqued by its opponents who identified two major drawbacks: First, the term patient-reported experience can be used interchangeably with the terms ‘patient satisfaction’ and ‘patient expectation’, both of which are subjective terms reflecting judgments on the appropriateness of health care rather than its efficacy [Citation2]. Second, patients’ own hypotheses about their health condition are reflected in PREMs rather than their actual treatment experience [Citation2]. These drawbacks reveal smudging of concept and abrupt notion changing [Citation2]. This reflects a lack of idea maturation in terms of patient-reported experiences and, hence it becomes an area that should be further explored [Citation2]. Despite these limitations, PREMs are internationally acclaimed as valid parameters to evaluate quality of care [Citation2,Citation3]. This is primarily due to the following reasons: PREMs (a) reflect the importance of quality assessment and care; (b) allow patients to precisely reflect on the interpersonal aspects of their care experience; and (c) can provide patient information that can be used to drive improvement strategies in care quality [Citation2,Citation3]. PREMs are definitely an indicator of patient care, but they do not directly quantify it [Citation4]. They are usually in the form of questionnaires. In contrast to PROMs (patient reported outcome measures), PREMs focus on the impact of the care process on the patient’s experience, such as communication and care timeliness [Citation4]. Patient experience comprises both patient’s experience of treatment and patient feedback on those experiences [Citation4]. PREMs revolve around patient experience on both ‘what’ occurs to the patient and ‘how’ the patient reports that experience [Citation4]. This underlines the foggy distinction between the ideas of ‘patient experience’ and ‘patient satisfaction’ [Citation4]. Although the terms are frequently used interchangeably, they are different, and the nature and direction of their relationship are still contested [Citation4].

How can we measure ‘patient experience’?

Data about patient experiences may be collected in a variety of ways. Patients’ perspectives are regularly explored via surveys in regular clinical practice [Citation4]. However, technological advancements have made it swifter as the surveys can now be performed through patients’ phones (messages), internet, or the use of portable devices to collect data [Citation4]. Researchers frequently opt for subjective interviews as consistently collecting and analysing data through surveys is costlier [Citation4]. When compared to the findings of surveys, data acquired through interviews more commonly result in reports of negative experiences with care [Citation4,Citation5] Patient experience can influence clinical results [Citation4,Citation5]. Effective clinician-patient communication, for example, can influence health outcomes such as emotional health, pain beliefs, pain coping and function [Citation5].

Tools to measure ‘patient experience’

The Nordic Patient Experiences Questionnaire (NORPEQ) (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3367149/; Appendix A) comprises a core set of questions that addresses the most important aspects of patient experiences [Citation6]. Based on a rigorous questionnaire preparation and review approach that includes forward and backward translation, degrees of missing data analysis, dimensionality, internal and construct validity, the NORPEQ demonstrates good evidence of reliability and validity [Citation6]. The Picker Patient Experience (PPE-15) (https://academic.oup.com/intqhc/article/14/5/353/1800673, Appendix B) showed acceptable validity and reliability [Citation2]. While patients reported problems with all PPE-15 items, problems with discharge information were very common [Citation2]. Education and information, coordinated care, respecting the patient’s wishes, emotional comfort, physical ease and involvement of significant ones are the fundamental components of PPE-15 [Citation2]. It is a helpful method for assessing inpatient experience that is widely used to assess hospital service quality [Citation2]. Concerns are raised by the fact that many PREMs have been produced for the same patient group with little regard for measure validation [Citation2]. Future research should consider the most promising existing PREMs as a foundation for developing new measures [Citation2]. Furthermore, research should focus on developing PREMs for a specific diseases or conditions [Citation7]. The importance of ‘Context’ is undoubted in influencing the patient’s perception about the care they receive [Citation7]. This signals the need of developing PREM tools that are ethno-culturally suited, are preferably in patients’ own language (regional language) and most importantly with which the community can relate [Citation7]. These culturally sensitive PREM tools will lead to patient centred treatment approaches, improved clinical efficacy and quality of care [Citation7].

Ethnic, racial and socioeconomic facets of patient experience

Although documenting patient experience can lead clinicians on the path of holistic patient care, it is critical to understand the complexities of the information gathered [Citation8]. A group of younger patients from ethnic minorities and from lower socioeconomic status is likely to report more negative experiences [Citation8]. This might be because they receive poorer treatment, or because the expectations of certain demographic groups differ, or because they perceive survey questions differently [Citation8]. Various populations display wide-ranging care expectations [Citation8].

Asian patients reported higher negative ratings of waiting times than White patients, even when the actual waiting durations reported by the groups were comparable [Citation8]. Patient–physician racial/ethnic coherence is linked to patients’ perceived experience with their physicians [Citation8]. Physicians in incompatible pairs were less likely to receive the highest patient rating than physicians in racially/ethnically compatible patient–physician interactions [Citation8]. White patients who came to Asian or Black doctors were less likely to view their doctors positively than White patients who saw White doctors; the latter difference was statistically significant [Citation8]. Black patients who saw White or Asian physicians were less likely to rate their physicians favourably compared with those who saw Black physicians [Citation8]. Various demographic groups may place more emphasis on particular components of treatment than others – for example, less educated patients may place a higher relative value on continuity of care than more educated patients [Citation8]. In addition to ethnicity, additional characteristics to evaluate in the context of case-mix include age, gender, self-reported health status, and the prevalence of persisting psychiatric or emotional problems [Citation8]. Individuals with modest earnings had a much higher risk of experiencing difficulties receiving medical treatment, poor communication with medical professionals, low participation in decisions, delayed medical care, and decreased contentment with the care they received as compared to those with high income [Citation9]. These inequalities are continued irrespective of the patient’s age, race or ethnic background, gender, co-morbidity load or insurance status [Citation9]. There is an empathy gap for patients with socioeconomic disadvantage. Patients with low incomes had considerably lower patient-reported judgments of physician empathy than patients with higher socioeconomic status [Citation9].

How can patient experience data be used to improve quality of care?

In 2001, the NHS in England was among the first to implement a national patient survey, with the United States following suit with its own national Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) [Citation10]. Nevertheless, collecting patient experience data is the initial but essential step to understanding challenges and opportunities to improve healthcare quality [Citation10]. Public reporting of patient experience in combination with an array of interventions that take in to consideration the context of a healthcare system may have greater potential to stimulate providers to improve quality [Citation10]. Patient experience is an important aspect of quality of care. There continues to be much work needed to refine our approaches to defining and measuring patient experience [Citation10,Citation11].

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ahmed F, Burt J, Roland M, et al. Measuring patient experience: concepts and methods. Patient. 2014;7(3):235–241. doi: 10.1007/s40271-014-0060-5.

- Bull C, Byrnes J, Hettiarachchi R, et al. A systematic review of the validity and reliability of patient‐reported experience measures. Health Serv Res. 2019;54(5):1023–1035. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.13187.

- Kingsley C, Patel S. Patient-Reported outcome measures and patient-reported experience measures. BJA Educ. 2017;17(4):137–144. doi: 10.1093/bjaed/mkw060.

- LaVela SL, Gallan AS. Evaluation and measurement of patient experience. Patient Exp J. 2014;1(1):28–36.

- Skudal KE, Garratt AM, Eriksson B, et al. The Nordic Patient Experiences Questionnaire (NORPEQ): cross-national comparison of data quality, internal consistency and validity in four Nordic countries. BMJ Open. 2012;2(3):e000864. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-000864.

- Leonardsen A-CL, Grøndahl VA, Ghanima W, et al. Evaluating patient experiences in decentralised acute care using the Picker Patient Experience Questionnaire; methodological and clinical findings. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):685. doi: 10.1186/s12913-017-2614-4.

- Takeshita J, Wang S, Loren AW, et al. Association of racial/ethnic and gender concordance between patients and physicians with patient experience ratings. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(11):e2024583. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.24583.

- Okunrintemi V, Khera R, Spatz ES, et al. Association of income disparities with patient-reported healthcare experience. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(6):884–892. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-04848-4.

- Browne K, Roseman D, Shaller D, et al. Analysis & commentary. Measuring patient experience as a strategy for improving primary care. Health Aff. 2010;29(5):921–925. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0238.

- Llanwarne NR, Abel GA, Elliott MN, et al. Relationship between clinical quality and patient experience: analysis of data from the English quality and outcomes framework and the national GP patient survey. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11(5):467–472. doi: 10.1370/afm.1514.

- Tefera L, Lehrman WG, Conway P, et al. Measurement of the patient experience: clarifying facts, myths, and approaches. JAMA. 2016;315(20):2167–2168. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.1652.