Abstract

During adolescence, social relationships become increasingly important. The words teens use with each other become important to identity and group belonging. Teens who use augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) often have smaller social circles than typically-developing teens and may have limited access to the vocabulary used by their peers. This study aimed to understand more about the types of words used in peer interactions by typically-developing teens and explore their perceptions of how and why word use is important in peer interactions. Direct observation and focus group interviews were undertaken with a sample of 25 teens aged 12–15 years in Perth, Western Australia. Observation data identified frequently used word types, according to Tagliamonte’s markers of teen language. Focus group interviews described three key reasons participants viewed word choices as important, highlighting the role of vocabulary in everyday peer interactions. It is vital for speech pathologists and others working with teens who use AAC to understand how teen-specific language is used within each individual’s peer group, and the value of this vocabulary in supporting peer relationships.

Introduction

Adolescence marks an important life stage as children seek autonomy, establish their own identity and increasingly value peer relationships (Gray et al., Citation2017). Social relationships underpin the development of identity with teen-specific language playing a crucial role in social belonging (Postmes et al., Citation2005). Conversely, an inability to use appropriate peer language may act as a barrier to acceptance, emphasising the importance of language choices in forming and maintaining social relationships (Durkin & Conti-Ramsden, Citation2007).

For teens who use augmentative and alternative communicationFootnote1 (AAC), adolescence poses additional challenges, due to the central role communication plays in social relationships (Smith, Citation2015; Therrien, Citation2019). Challenges in social interactions described by AAC users highlight issues with the speed of communication and the availability of relevant vocabulary on the AAC system (Look Howery, Citation2015; Therrien, Citation2019). Supporting AAC users in developing peer relationships is important, as AAC-using children and teens have been shown to communicate largely with family and adult supporters, rather than acquaintances or friends (Raghavendra et al., Citation2011, Citation2012).

Supporting AAC users to develop rich ongoing connections and meaningful friendships is an important research and clinical direction. Therrien et al. (Citation2023) call on speech-language pathologists (SLPs) to develop a ‘friendship mindset’ when working with people who use AAC. They suggest, when working with teens, SLPs should ensure relevant vocabulary and quick talk is available for peer greetings and fleeting peer interactions in school. Such frequent, brief contacts are important to developing connections and allow ‘AAC users an opportunity to be part of this social world’ (Therrien et al., Citation2023, p. 158). Vocabulary on AAC systems should be tailored to the individual, based on an understanding of the words needed to support everyday interactions, acknowledging that vocabulary needs to change across life stages (Bean et al., Citation2019).

AAC systems may include a mix of core and fringe vocabulary, quick talk phrases and the alphabet to ensure that people have access to robust and rapid communication (Hill & Romich, Citation2000; Hartmann, Citationn.d.). Core vocabulary refers to the approximately 250–300 words that we use 70–80% of the time and that can be used across communicative situations (Bean et al., Citation2019; van Tilborg & Deckers, Citation2016). Core vocabulary typically includes commonly used verbs, adjectives/adverbs, prepositions, pronouns, and conjunctions (Hartmann, n.d). However, fringe vocabulary, the highly specific words we use, is also important in personalising AAC systems. Fringe vocabulary often consists of nouns and is highly specific to the interests and activities of each individual (Hartmann, n.d.). Ensuring relevant fringe words and common phrases are available within an AAC system is crucial (Look Howery, Citation2015; Therrien, Citation2019) as AAC users have indicated that they may have limited access to teen vocabulary (Wickenden, Citation2011). However, decisions about which vocabulary to include on AAC systems to promote peer interactions are not straightforward.

For many AAC users, decisions about which vocabulary is included in an individual’s AAC system are shaped by adult informants in the person’s life, such as a parent, therapist, or teacher (Look Howery, Citation2015; Wickenden, Citation2011). If others do choose vocabulary for teens (substitute decision-making), this raises issues of autonomy, particularly as teens often desire increased independence (Gray et al., Citation2017). However, there is limited research exploring what processes are used for vocabulary selection with teens who use AAC. Importantly, Therrien et al. (Citation2023) describe the need to collaborate with teen AAC users, peers and teachers to identify vocabulary that may facilitate peer interactions. Such collaboration is vital, given the emergence of teen-specific vocabulary that adults informants may be unaware of.

A teen-specific vocabulary emerges during adolescence (Smith, Citation2005; Tagliamonte, Citation2016). Tagliamonte (Citation2016) identified features of language that dominates talk between teens, including quotative verbs (e.g. I was like, oh my God!), increased use of intensifiers (e.g. It was really good), frequent use of discourse markers such as sentence starters (e.g. One time I did that) and finishers (e.g. I wasn’t feeling that good, you know?); increased use of adjectives/adverbs (e.g. That’s a weird dog), and the use of social and slang phrases. The term ‘slang’ is commonly used to describe the casual words, phrases, and abbreviations used by youth and teenagers (Davie, Citation2019).

Teen specific vocabulary may vary according to factors such as geography, gender, cultural background, and socioeconomic status (Eckert, Citation2000; Tagliamonte, Citation2016). There is currently little information about which types of words may be important to consider with teens who use AAC to promote social interactions, particularly those fleeting but meaningful interactions described by Therrien et al. (Citation2023). An understanding, and examples, of the types of words that may be important in teen interactions and why they are seen as important by teens may be useful to consider when collaborating with AAC users, to plan AAC vocabulary that can support communication with peers.

This study explored the nature of vocabulary used in peer-interactions of typically-developing teens in Perth, Western Australia. Specifically, it sought to understand:

What types of words are frequently used by typically-developing teens aged 12–15 years in peer interactions, according to Tagliamonte’s markers of teen language (2016)?

What are the perceptions of typically-developing teens aged 12–15 years about how and why vocabulary contributes to peer interactions?

Materials and method

A simultaneous qualitative mixed methods design was used (Morse, Citation2010). Two types of qualitative data were collected: observational data and focus group interview data.

Recruitment

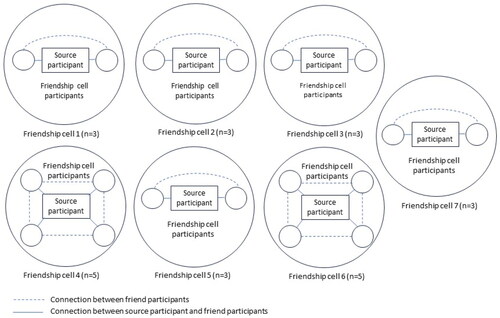

Friendship cell sampling was used to recruit groups of participants (Jones et al., Citation2018). Friendship cell sampling initially recruits a source participant, who subsequently invites members of their social network to join the study, forming a friendship cell/group. Source participants were recruited via personal networks of the research team. Individuals were included if they were aged between 12–15 years, and identified as male, typically-developing, and as a fluent English speaker. Gender was a selection criterion due to its influence on teen vocabulary (Eckert, Citation2014). Non-source participants were also required to have an existing friendship with a source participant.

Participants

Twenty-five participants, across seven friendship cells, were included, with one source participant and 2–6 friendship cell participants per group (see ). Participants ranged in age from 12 years, 5 months to 15 years, 11 months, with a mean age of 14 years 10 months. Demographic information is provided in . All participants resided in the greater Perth metropolitan area, with participants living in a range of areas, including the eastern suburbs and hills area (n = 6, 24%); southern suburbs (n = 10, 40%), western suburbs (n = 9, 36%). No other socioeconomic indicators (e.g. parent education level and income data) were collected.

Table 1. Participant demographic information.

Data collection

Data were collected in the home of each source participant. One group was conducted online due to COVID-19 restrictions, others were conducted face-to-face. One session was conducted per group, lasting approximately 1.5 hours and including two researchers (L.C and T.J.). Each session comprised (1) direct observation of conversations and (2) a focus group interview. All sessions were audio-recorded.

Direct observation

Two researchers observed peer conversations. Direct observation of activities is used to capture observable behaviours (Guest et al., Citation2013). Participants were offered suggested activities to create a shared focus and promote comfort while being observed. A gaming activity (Minecraft/Fortnite) was proposed to encourage conversation while interacting via a frequently used medium. Four groups interacted using gaming, however three groups chose to commence via social discussion. Conversation topics during/after gaming for participants using this activity were wide ranging and not always linked to the game. Groups then chose whether they wished to view and discuss one of two pre-selected YouTube clipsFootnote2. All groups undertook this activity, with groups choosing which clip they would watch. Conversations during the task were again wide ranging. Researchers did not attempt to restrict participants to pre-determined topics. During observations, researchers noted examples of Tagliamonte’s (Citation2016) markers of teen language to provide exemplars of vocabulary during focus group interviews. Average direct observation time was 40 minutes.

Focus group interviews

Focus group interviews used a purpose-designed topic guide (supplementary materials) based on Tagliamonte’s (Citation2016) markers of teen language. Focus groups explored teen perceptions about words and phrases used in peer interactions and perceptions of vocabulary used with peers. Average focus group time was 30 minutes.

Analysis

Recordings were manually transcribed verbatim, with 20% of transcriptions checked for accuracy by another researcher. Qualitative content analysis was used to analyse all data, using three phases: (1) preparation phase; (2) organising phase; and (3) reporting phase (Elo & Kyngäs, Citation2008). All coding and grouping of data were done collaboratively by two researchers (L.C. and T.J) with a third researcher (M. I) acting as adjudicator for any disagreements. Later analytic stages were completed with the whole research team. Findings are presented as categories of data.

Observational data

Deductive coding was used (Kennedy, Citation2018), where words and recurrent phrases, consistent with categories described by Tagliamonte (Citation2016), were identified collaboratively and organised in NVivo software (version 12, QSR International, 2019, https://techcenter.qsrinternational.com/Content/welcome/toc_welcome.htm). Frequency counts of Tagliamonte’s (Citation2016) categories were tabulated both across and within-groups. The twenty most frequent words, the distribution across groups, and categorisation according to the Tagliamonte framework (2016) are presented in this paper.

Focus group data

Inductive coding, drawing meaning directly from transcripts (Kennedy, Citation2018), was used. Transcripts were reviewed collaboratively with relevant statements identified. Open coding, labelling the meaning inherent in the text, was completed using NVivo software. Codes were repeatedly refined. A codebook was used to support consistency of coding. An audit trail was used to promote transparency in decision-making. Similar codes were clustered and presented to the research team. Category labels were collaboratively developed/refined. The meaning central to data in each category was explored with reference to coded data, and summaries developed.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was obtained via the Human Research Ethics Office at Curtin University (HRE2022-0116). Study information was provided in clear accessible language. Source participants were provided with instructions about how to share information about the study, to minimise risk of coercion. Written consent was obtained from both participants and their parents/guardians. Consent was reconfirmed verbally at commencement of each data collection session.

Reflexivity statement

Four of our research team were speech pathology student researchers undertaking research for the first time. We were supported by an experienced research academic who actively engaged with us and the project. We recognised that our novice status, clinical rather than research orientation, and our youth may influence the ways we collected and interpreted data. We attempted to draw on the experience of our supervisor and other academics to build a deeper understanding of research. We used debriefing to reflect on experiences, maintained open/honest communication with our supervisor and constantly referred to study data as we began interpreting meaning categories during analysis.

Results

This study explored the nature of vocabulary used in peer-interactions of typically-developing teens in Perth, Western Australia and the perceptions of typically-developing teens aged 12–15 years about why vocabulary choices are important within peer interaction. Results are presented in two sections, linked to each research aim.

Types of words and phrases during peer interactions (observation data)

Frequency counts of the 20 most frequently used words consistent with Tagliamonte’s (Citation2016) categories across groups are presented in . The types of words used, by frequency, according to Tagliamonte’s (Citation2016) categories are presented in . Data in this table represent the total number of words within each category across the overall data set, beyond the twenty most frequent words.

Table 2. The twenty most frequently used words, with frequency counts and exemplars.

Table 3. Frequency of use by word category.

How and why vocabulary contributes to peer interactions (focus group data)

Participant perceptions of the contribution of vocabulary to peer interactions comprised three categories.

Category 1. Words used have social implications

Participants identified social implications linked to word choices. This included influences on social belonging and social comfort, with social consequences linked to inappropriate word choices/language use.

Subcategory 1. Vocabulary shows social belonging

The importance of using the same words to strengthen friendship and signifying social closeness was clear ‘It’s important …cause like you’re more in touch with them when you are using the same language (words)’ (Group 6). The impact on friendships was highlighted, ‘It (using the same words as peers) helps progress friendships a lot more.’ (Group 6). Group specific vocabulary was considered an indication of the social group someone related to, for example, ‘It’s (using particular words)… an association between themselves, as being further away from parents.’ (group 4). Participants described how swearing is used within social situations, identifying swearing as a rite of passage and as a symbol of social belonging.

Subcategory 2. Filling silence with words can reduce feelings of discomfort

Participants described using filler words and sentence starters/finishers to fill silences, reducing feelings of discomfort. ‘(Silence) makes it very uncomfortable, I feel like everyone would be very uncomfortable in …silence while you’re in a big group.’ (Group 5).

Subcategory 3. Vocabulary choices have social consequences

Potential negative social consequences were linked by participants to the use of ‘incorrect’ language in peer groups, for example,

Researcher: So do you think (word choices) makes a difference?

Participant: A big difference. First impressions are everything really, if you come up, there’s one kid in my class, he just talks really weirdly, like … he’s stuck in 2017 kinda stuff. No-one likes him.

(Group 3)

Category 2. Patterns of language change

Teens demonstrated an understanding of patterns of language use and the constant evolution of language.

Subcategory 1. Sociocultural elements influence vocabulary

Participants recognised language choices are influenced by cultural and geographical factors as well as gender, for example, ‘My dad says that all the time, it’s a New Zealander thing’ (group 2) and ‘It’s very different between boys and girls.’ (Group 1). Social media was also described as having a clear impact on words teens use, bringing certain vocabulary into social relevance.

Subcategory 2. Fast changing vocabulary

The importance of keeping up with changing patterns was clear. The use of text speech and abbreviations (e.g. LOL, described as ‘outdated’), were used as examples of rapidly shifting vocabulary. Teens indicated that there are windows of time where particular vocabulary is socially relevant, ‘Those (words) are kinda, like, old. Only like a couple of years but to us that’s very old.’ (Group 2)

Category 3. Words are used to help to manage conversations

Participants indicated that they consciously manipulate words for social purposes to manage conversation with peers in two ways.

Subcategory 1. Getting into the conversation

Teens indicated they use sentence starters such as ‘bro’ or ‘oi’ as a strategy to gain attention when initiating conversations, for example,

Participant: It’s like, um, a hook. ‘Hey bro, what up man?’.

Researcher: So you’re trying to get their attention?

Participant: Yup.

(Group 5)

Subcategory 2. Keeping conversations going

Participants described strategies to maintain peer conversations. Slang and swear words were seen to make messages more ‘interesting’ to peers. To maintain their conversational turn, participants described using filler words (e.g. um or like) to buy themselves time to think further and formulate what they wanted to say.

Participant 1: (discussing a friend) I think he said “like as” about nine times yesterday.

Participant 2: Yeah he says “like as” a lot.

Participant 1: Yeah, I don’t know why, I think he doesn’t really know his stories. I don’t think he has the time to realize what he’s talking about. You just use it when you are trying like, you know, communicate quickly, keep it (the story) going…y ’know it’s not like you’re coming up with sentences in your mind before you say it out loud.

(Group 5)

Discussion

This research provides preliminary information about the types of words used by a sample of typically-developing male teens aged 12–15 years in Perth, Western Australia. Specifically, it found that sentence starters/finishers, abbreviations and fillers were the most commonly used types of words in a sample of peer conversation. Participants described three reasons they perceived vocabulary to be important within peer interactions: words used have social implications; patterns of language change, and words are used help to manage conversations.

It is important to critically reflect on whether each of these frequently used markers of teen language may be relevant to teen AAC users, and how they may be of benefit. The three most frequent word types will be considered alongside focus group findings about perceived importance of vocabulary.

Sentence starters/finishers were the most commonly word type used in the study. Participants described using sentence starters to attract attention of peers and to enter conversations (Category 3). Given the difficulty with the pace of conversations described by AAC users, (Look Howery, Citation2015; Therrien, Citation2019) sentence starters (such as, ‘oi’ or ‘hey guys’) specific to the peer group of the individual may be useful vocabulary in AAC systems to assist with getting into conversations, a form of strategic competence (Light, Citation1989). In selecting specific vocabulary, it is important to envision how these sentence starters could be used in the fleeting peer interaction moments described by Therrien et al. (Citation2023) and to seek sentence starters that are relevant to the sociocultural background of the AAC user (Category 2).

Slang phrases were the second most frequent word type observed in the study. Access to locally relevant slang and abbreviations relevant to teens may be important to teen AAC users to show alignment and belonging in their social group, (category 1), an important concept in adolescence (Wickenden, Citation2011). Swear words, frequent in most groups in the study may be also desired by some teen AAC users, to delineate their individuality and teen identity (Wickenden, Citation2011). Issues of power, limiting access to vocabulary that may not be desirable for parents or teachers, but desired by teens becomes important to consider as children move towards adulthood, to ensure the autonomy of the individual is respected (Brewster, Citation2013).

In contrast, fillers, the third most common word type used, are unlikely to be helpful for teen AAC users to ‘hold’ their place in conversation (Category 3, focus group data). Using fillers would likely add to the already typically long duration required to construct messages for AAC users (Look Howery, Citation2015).

One notable finding, when considering individual word counts in the study, was the high frequency of use of the abbreviated words ‘yeah’ and ‘nah’ by participants. Abbreviated forms of words represent an important register shift, with no teen participant in the study using the word ‘yes’, or ‘no’ during data collection. Access to common abbreviated word forms may be useful to AAC users to promote social belonging (Category 1), as using the ‘right’ words is seen to promote social belonging both in this study and in the wider literature (Postmes et al., Citation2005).

While not a specific aim of the research, this paper has presented a novel approach to exploring peer vocabulary that may be adapted to clinical situations, reflecting Raghavendra’s et al. (Citation2011, Citation2012) approach using circles of support. Working collaboratively with an AAC users and their peers to form friendship groups to describe useful patterns of vocabulary specific to their friendship group for social communication would be clinically useful and move away from adult informed vocabulary selection practices (Look Howery, Citation2015; Wickenden, Citation2011).

While data were collected with typically-developing teens, the underlying intent of the study was to provide insight into the specific types of vocabulary (eg. slang, sentence starters and finishers) that may be helpful for teen AAC users to consider including in their systems to promote peer interactions. The description by participants of how these words are used in interaction may offer some insight as to why particular types of vocabulary may be important to include on AAC systems to support peer interactions, however much more research is required.

Limitations

This study is a small-scale study with a range of limitations. Findings should be interpreted with caution. The research involved a small sample, limited to one gender, in Perth Western Australia. Socioeconomic data were not collected but defacto indications (e.g. high rates of private school attendance) are suggestive of a high-income sample. Future studies should collect socioeconomic data to assist with sample description. Vocabulary is likely to be sample or context specific. Additional contrasting samples would be useful to build out the corpus of vocabulary. Additionally, the language sample collected during observations within a limited timeframe may not be representative of participants’ language use across longer periods. Variation in activities may have contributed to variability in vocabulary observed. Moving directly from an observation session to a focus group did not allow researchers time to reflect on vocabulary observed in the session. Data collection across two successive appointments may have allowed researchers to understand preliminary data prior to the focus group. While the study considered vocabulary of a sample of typically-developing teens, the intent was to consider how this knowledge may inform considerations of vocabulary that may be beneficial for AAC users to support peer relationships. Yet, we do not yet understand if teen AAC users aspire to have the same styles of communication as their typically-developing peers.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (158.2 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Kelly Savage who was the instigator of this project, following clinical concern about a lack of evidence about vocabulary to support peer interaction. We also wish to acknowledge the valuable contributions of Todd Jackson and Anna Chapman who were part of the honours group that undertook this project.

Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Data availability statement

Data are available from the authors on request.

Notes

1 AAC refers to the range of multimodal tools and strategies used by people with complex communication needs to support everyday communication (Speech Pathology Australia, Citation2020).

2 XDubai. (2015, April 28). Dream jump. Dubai – 4K. [video]. YouTube.

www.youtube.com/watch?v=Fhskvloj1gE.

Brick General. (2020, March 23). Best TEEN RATED games of 2020! [video]. YouTube.

References

- Bean, A., Cargill, L. P., & Lyle, S. (2019). Framework for selecting vocabulary for preliterate children who use augmentative and alternative communication. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 28(3), 1000–1009. https://doi.org/10.1044/2019_AJSLP-18-0041

- Brewster, S. (2013). Saying the ‘F word … in the nicest possible way’: Augmentative communication and discourses of disability. Disability & Society, 28(1), 125–128. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2012.736672

- Davie, J. (2019). Slang across societies (1st ed.). Routledge.

- Durkin, K., & Conti-Ramsden, G. (2007). Language, social behaviour, and the quality of friendships in adolescents with and without a history of specific language impairment. Child Development, 78(5), 1441–1457. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.467-8624.2007.01076.x

- Eckert, P. (2000). Linguistic variation as social practice: The linguistic construction of identity in Belten High (1st ed.). Blackwell.

- Eckert, P. (2014). Language and gender in adolescence. In S. Ehrlich, M. Meyerhoff, & J. Holmes (Eds.), The handbook of language, gender, and sexuality (2nd ed., pp. 529–545). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118584248.ch27

- Elo, S., & Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), 107–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

- Gray, S., Romaniuk, H., & Daraganova, G. (2017). Adolescents’ relationships with their peers. In D. Warren & G. Daraganova (Eds.), Growing up in Australia. The longitudinal study of Australian children. Annual statistical report 2017. Australian Institute of Family Studies. https://growingupinaustralia.gov.au/sites/default/files/publication-documents/lsac-asr-2017.pdf

- Guest, G., Namey, E., & Mitchell, M. (2013). Collecting qualitative data: A field manual for applied research. Sage Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781506374680

- Hartmann, A. (n.d). 4 things every AAC system needs. Assistiveware. https://www.assistiveware.com/learn-aac/select-a-balanced-aac-system

- Hill, K., & Romich, B. A. (2000). AAC core vocabulary analysis: Tools for clinical use. Proceedings of the RESNA Annual Conference on Technology for the New Millennium (pp. 67–69.). RESNA Press.

- Jones, C. D., Newsome, J., Levin, K., Wilmot, A., McNulty, J., & Kline, T. (2018). Friends or strangers? A feasibility study of an innovative focus group methodology. Qualitative Report, 23(1), 98–112. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2018.2940

- Kennedy, B. L. (2018). Deduction, induction, and abduction. In U. Flick (Ed.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative data collection (pp. 49–64). SAGE. https://doi.org/10.4125/9781526416070

- Light, J. (1989). Toward a definition of communicative competence for individuals using augmentative and alternative communication systems. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 5(2), 137–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/07434618912331275126

- Look Howery, K. L. (2015). Speech-generating devices in the lives of young people with severe speech impairment: What does the non-speaking child say?. In D. L. Edyburn (Ed.). Efficacy of assistive technology interventions (Vol. 1, pp. 79–109). Emerald Group Publishing.

- Morse, J. M. (2010). Simultaneous and sequential qualitative mixed method designs. Qualitative Inquiry, 16(6), 483–491. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800410364741

- Postmes, T., Spears, R., Lee, A. T., & Novak, R. J. (2005). Individuality and social influence in groups: Inductive and deductive routes to group identity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89(5), 747–763. https://doi.org/10.1037/022-3514.89.5.747

- Raghavendra, P., Olsson, C., Sampson, J., Mcinerney, R., & Connell, T. (2012). School participation and social networks of children with complex communication needs, physical disabilities, and typically-developing peers. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 28(1), 33–43. https://doi.org/10.3109/07434618.2011.653604

- Raghavendra, P., Virgo, R., Olsson, C., Connell, T., & Lane, A. E. (2011). Activity participation of children with complex communication needs, physical disabilities and typically-developing peers. Developmental Neurorehabilitation, 14(3), 145–155. https://doi.org/10.3109/17518423.2011.568994

- Smith, M. M. (2005). The dual challenges of aided communication and adolescence. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 21(1), 67–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/10428190400006625

- Smith, M. M. (2015). Adolescence and AAC: Intervention challenges and possible solutions. Communication Disorders Quarterly, 36(2), 112–118. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525740114539001

- Speech Pathology Australia. (2020). Augmentative and alternative communication clinical guideline.

- Tagliamonte, S. (2016). Teen talk. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139583800

- Therrien, M. C. (2019). Perspectives and experiences of adults who use AAC on making and keeping friends. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 35(3), 205–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/07434618.2019.1599065

- Therrien, M., Rossetti, Z., & Østvik, J. (2023). Augmentative and alternative communication and friendships: Considerations for speech-language pathologists. Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interest Groups, 8(1), 151–163. https://doi.org/10.1044/2022_PERSP-22-00105

- van Tilborg, A., & Deckers, S. R. (2016). Vocabulary selection in AAC: Application of core vocabulary in atypical populations. Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interest Groups, 1(12), 125–138. https://doi.org/10.1044/persp1.SIG12.125

- Wickenden, M. (2011). Whose voice is that? Issues of identity, voice and representation arising in an ethnographic study of the lives of disabled teenagers who use augmentative and alternative communication (AAC). Disability Studies Quarterly, 31(4). https://doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v3li4.1724