Abstract

Social networking is the new norm of the society as many of us remain “online” 24*7. However, excessive use of it would result in social networking addiction. There are some existing tools to measure social networking addiction but all of them suffer from conceptual or/and methodological problems. The present research aimed at developing a theoretically and psychometrically sound tool to assess social networking addiction by conducting three different studies. Study 1 established the factor structure of the social networking addiction scale as a higher-order construct having six first-level factors. In study 2, we found that social networking is a relatively enduring characteristic as test-retest reliability was found to be. 88 in a time span of 25 days. Study 3 was conducted to establish the convergent and divergent validity of the social networking addiction scale (SNAS). Problematic internet use, Facebook addiction, average time spent on the internet daily and loneliness were chosen to test the convergent validity of SNAS, while life satisfaction was used to test the divergent validity. The result establishes the convergent and divergent validity of SNAS. The scale situated nicely between problematic internet and Facebook addictions as it shared 53% of the variance with the former and 25% with the later.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Need to belong and to connect with other fellow humans is one of the most important social needs people have. In the technology mediated world, this need is largely fulfilled through different social networking websites and applications. “Being Online” 24*7 is a new normal in today’s contemporary world. While it is useful and the need of the hour for many, the overuse of the same has adverse effects on the well-being of individuals with them actually becoming addicted to it. The social networking addiction scale was developed after a thorough scrutiny of the already existing scales or questionnaires. The developed social networking addiction scale has undergone an initial validation and it would help researchers and practitioners to identify possible cases of social networking addiction by looking into different dimensions of behavioral addiction which would help in proper intervention.

1. Introduction

Social networking sites (SNSs) and applications have become an essential means of social contact and communication in today’s contemporary world. SNSs are virtual communities where users can create individual public profiles, interact with real-life friends and meet people (Kuss & Griffiths, Citation2011). Social networking applications and sites such as Facebook, Twitter, WhatsApp, Instagram, and Snapchat have enabled people, especially the younger generation to interact by just a click or touch of a button, making them instantly connect to the whole world. All this has only been possible because of easy access to the internet, which has also become affordable over the years.

The present day world is technology mediated, and the basic human need of socializing is largely done through technology. Being “online” is the new norm (Kuss & Griffiths, Citation2017) as many young people report that they hardly turn off their smartphones, sleep with their smartphone next to them, and also compulsively check their smartphones throughout the day (Carbonell et al., Citation2012). Social networking is the main reason that drives people to use their smartphones regularly (Andreassen et al., Citation2013; Griffiths et al., Citation2014). However, some people use it excessively and may have become addicted to it (Cerniglia et al., Citation2019; Kuss & Griffiths, Citation2011, Citation2017; Sussman et al., Citation2011). The study of Davies and Cranston (Citation2008) found that engagement in social networking may hamper face-to-face interactions and other activities among practitioners and managers. The study also found that 23% of the participants reported addiction as a primary concern.

2. Social networking and other terms

To denote excessive use of SNSs, various researchers have used different terminologies such as SNSs addiction, problematic use of SNSs, and compulsive use of SNSs. In the current research, we are not entering into this debate of which terminology is better than the rest, as we assumed that SNSs use can be considered an “addiction” if they fit into the framework of behavioral addiction model (Griffiths, Citation2005). The detailed description of this model has been presented later in the paper, as the present research is based on this model. However, some clarity regarding the terminology is needed among social networking, social media as well as Facebook usage, as they are often used interchangeably. Despite being used interchangeably in the scientific literature, social media and social networking are not the same (Kuss & Griffiths, Citation2017). Social media refers to web 2.0 capabilities of producing, sharing, and collaborating online content. Therefore, social media usage includes a wide variety of social applications such as collaborative projects, weblogs, content communities, social networking sites, virtual game worlds, and virtual social worlds (Kaplan & Haenlein, Citation2010; Kuss & Griffiths, Citation2017; Monacis et al., Citation2020). Thus, social networking is just one of the applications of social media, implying that social media is more generic in nature while social networking is one of the specific uses of social media. Similarly, Facebook is not all the “social networking” platforms, but rather just one of the social networking sites in addition to Instagram, Whatsapp, Twitter, etc. The study of Donnelly and Kuss (Citation2016) found that the usage of Instagram is potentially more addictive among the United Kingdom (U.K.) young adults than the usage of Facebook. Also, Smith and Anderson (Citation2018) reported that there was a 7% increase in the usage of Instagram between 2016 and 2017 among United States participants. Hence, it can be said that the social networking addiction is neither social media addiction nor a Facebook addiction.

3. Conceptual framework

As we all live a technology mediated life, there is a concern that the normal use or even excessive use of social network by enthusiastic users are unnecessarily been pathologized (Kardefelt-Winther et al., Citation2017). However, there is empirical evidence that for some of the users, social networking is the most important activity of their lives and when they use it, they lose a sense of time and self that adversely affects their daily functioning (Andreassen et al., Citation2013; Griffiths et al., Citation2014) and thus, social networking addiction (SNA) can be considered a valid case of addiction. Andreassen (Citation2015) also opined that the occasional social network enthusiasts will have more control over their usage and therefore would not have negative consequences. Despite the fact that the problem of SNA is real, but research on SNA suffer from many methodological problems (Kuss & Griffiths, Citation2017). The major problem being that different researchers have used different conceptualizations, different measurement instruments and different cut-off points, thus, hampering the growth of the subject and also challenging the construct validity of SNA as a genuine addiction (Kuss & Griffiths, Citation2017). Griffiths (Citation2005) presented a model of behavioral addiction comprising of six criteria being salience, mood modification, tolerance, withdrawal, relapse, and conflict, which can be used in the context of social networking addictions (Kuss & Griffiths, Citation2011). According to Griffiths et al. (Citation2014), “any behavior (e.g., social networking) that fulfills the aforementioned six criteria can be operationally defined as an addiction” Pg. 121. Also, there is evidence that these six criteria have been used to define and measure many behavioral addictions such as Exercise (Griffiths, Citation2005), Shopping (Clark & Calleja, Citation2008), Work (Andreassen et al., Citation2012a), Facebook addiction (Andreassen et al., Citation2012b), Mobile phone addiction (Billieux et al., Citation2015), Internet addiction (Kuss et al., Citation2013), Internet gaming disorder (Monacis et al., Citation2016), Social media (Andreassen et al., Citation2016), etc. By taking lead from these, we propose that social networking addiction can also be examined with the help of the six criteria of behavioral addiction. A brief introduction of the six criteria is as follows. However, for a detailed description see Griffiths (Citation2005)

1. Salience: When social networking would dominate one's life (thoughts, feelings and behaviours). Even if the person is not actively engaged in SNSs, he or she would only think about the same. 2. Mood modification: When usage of SNSs would modifiy and enhance one’s mood, such as bad to good. 3. Tolerance: When increased amount (usage of SNSs) would be required to get previous effects. 4. Withdrawal symptoms: Unpleasant feeling when one is unable to use SNSs because of network or dried battery etc. 5. Conflict: When SNSs would cause conflict in real life relations or other activities such as academics, work or relationships. 6. Relapse: Revert to SNSs after attempts of controlling SNSs.

4. Measurement concerns and the current study

There are four kinds of tools available to measure the construct under study. There are some tools that measure generalized internet addiction such as Internet addiction scale (Young, Citation1998), Pathological Internet Use Scale (Morahan-Martin & Schumacher, Citation2000), Online Cognition Scale (Davis et al., Citation2002), Internet-Related Problem Scale (Armstrong et al., Citation2000), etc. Since, Facebook has recently been one of the most popular mediums, many measures have been developed to measure Facebook-related addiction (Çam & Isbulan, Citation2012; Andreassen et al., Citation2012b; Sofiah et al., Citation2011). The two measures that assess generalized social media addiction are Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale (Andreassen et al., Citation2016) and Social media disorder (Van den Eijnden et al., Citation2016). Also, There are some tools that measure social networking addiction such as Addictive tendencies toward SNS (Wu et al., Citation2013) and Social networking addiction scale (Shahnawaz et al., Citation2013). However, a closer look at these tools revealed that none measured social networking addiction except the last two. The first category of tools measures generalized internet addiction while the second category of tools measures a very specific SNS that is Facebook. The third category of tools which are of recent origin measure social media addiction. The two tools of this category (Bergen social media addiction scale and social media disorder scale) have been discussed at length at the end of this section. In a review on social networking sites, Kuss and Griffiths (Citation2017) categorically stated that “social networking and social media use have often been interchangeable in the scientific literature, but, they are not same” Pg. 2. Also, they stated that “Facebook addiction is only one example of SNS addiction.” Pg. 7. We have already critically argued this in the earlier section of the paper under the subheading of “social networking and other terms.” Thus, neither of these three approaches capture the essence of social networking addiction.

Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale (BSMAS) (Andreassen et al., Citation2016) is a social media addiction scale, but social media has been defined as the use of Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, etc. Therefore, BSMAS can be considered a SNA scale despite being called a social media addiction scale. BSMAS is an adaptation of Bergen Facebook addiction scale (BFAS) (Andreassen et al., Citation2012b). In BSMAS, the term “Facebook” has been replaced with “Social media” in all items of the scale. There is one item each for six components of behavioral addiction (Andreassen et al., Citation2016). BSMAS has also been validated in different cultural samples such as Norway, Italy, Persia, and Hungry (Andreassen et al., Citation2016; Bányai et al., Citation2017; Lin et al., Citation2017; Monacis et al., Citation2017). However, using a single-item to tap each of the six components of behavioral addiction may under-represent the content boundary of the construct (Kaplan & Saccuzzo, Citation2018). To use single item or multiple items to measure a construct has been a debatable issue in behavioral science. Nunnally (Citation1978) noted that “other things being equal, a long test is a good test” Pg. 243. It seems logical also from the content domain perspective of classical test theory because more items would tend to cancel random errors. However, this conventional wisdom has been challenged conceptually and empirically (Bergkvist & Rossiter, Citation2007). There is evidence that in many cases, single-item measures are better than multiple items (Gardner et al., Citation1998). For example, single-item measure of job satisfaction measure was found to be superior than multiple items of job satisfaction (Scarepello & Campbell, Citation1983; Wanous et al., Citation1997). Without entering into this debate, it can be said that if a construct is concrete, then single item can be used to measure the construct instead of multiple items (Rossiter, Citation2002) and there are many criteria of doing so (Diamantopoulos et al., Citation2012). As mentioned earlier, BSMAS is the adaptation of Bergen Facebook addiction scale (BFAS) (Andreassen et al., Citation2012b). There were three items each for the six components of behavioral addiction initially in the BFAS; however, only six items, one each from the six dimensions were selected for the final scale based on the highest factor loadings of the items in that study (Andreassen et al., Citation2012b). The statistical way of choosing single item is not tenable as many times factor loadings or communality would vary across samples (Diamantopoulos et al., Citation2012). Therefore, BSMAS having six items is not tenable especially when each of the six dimensions is multifaceted. For example, salience refers to the fact that when social networking becomes the most dominant activity for the person and affect their thinking (e.g., cognition), feelings (e.g., cravings), and behavior (e.g., deterioration of social behavior) (Griffiths, Citation2005). In BSMAS, salience is measured by “ … spent a lot of time thinking about social media or planned use of social media” (Andreassen et al., Citation2016). Thus, it measures cognitive and behavioral aspects of the salience dimension, but left out the feelings part of salience. Moreover, as both the cognitive and behavioral aspects have been added in one item, thus this is a case of double-barrelled items which may cause confusion in the minds of the respondents. Mood modification captures both the experience of arousing buzz or a high and also a mean to avoid negative feelings (Griffiths, Citation2005). BSMAS measures mood modification with “ … used social media to forget about personal problems.” This item only measures the avoidance part of mood modification. Withdrawal symptoms refer to the unpleasant feelings and/or physical effects which occur when the social networking is discontinued or suddenly reduced (Griffiths, Citation2005). BSMAS measures withdrawal symptoms by “ … become restless or troubled if you have been prohibited from using social media?”. Unpleasant feeling states can be many and so are the physical effects. Conflict dimension reflects intrapsychic as well as intra personal conflicts (Griffiths, Citation2005). “ … used social media so much that it has had a negative impact on your job/studies” is the item in BSMAS to measure conflict. This item measures the negative outcome of SNA for the person. Griffiths (Citation2005) identified three types of conflicts emanating from excessive social networking use and the negative outcome is just one of these. The other two being personal relationships (partner, children, relative, friends, etc.) and other social and recreational activities. Therefore, it can be concluded that social networking addiction and it’s six components are multifaceted and single-item measure in the form of BSMAS grossly under-represent the construct domain of it. However, BSMAS is still useful because of its brevity especially when time and space are at a premium. But under other conditions, a more robust tool having multiple items capturing the nuances of all the six dimensions of behavioral addiction should be used.

Social media disorder (SMD) scale (Regina et al., Citation2016) also needs to be examined carefully. There are two versions of the scales, first, a full scale with 27 items and second, a shorter version with 9 items. It’s surprising that the term social media has not been defined at all by the authors of this scale unlike BSMAS and we know that social media is a very wide concept including collaborative projects, weblogs, content communities, social networking sites, virtual game worlds, and virtual social worlds (Kaplan & Haenlein, Citation2010; Kuss & Griffiths, Citation2017). Social media is too generic a term and it will be really difficult to compare, for instance, weblogs with social networking applications. Theoretically, they have used six behavioral addiction components (i.e., preoccupation/salience, tolerance, withdrawal, relapse, mood modifications, external consequences) and three criteria of internet gaming disorder (i.e., deception, displacement, and conflict), thus having six components. There is emerging consensus on the six criteria of behavioral addiction, however, same cannot be said for the Internet Gaming Disorder (IGD) criteria (Kuss et al., Citation2017), which the authors of the scale themselves acknowledged in the limitations of the study, “the nine DSM-5 criteria defined for IGD were translated to Social media disorder … however, these criteria are still subject to discussion” Pg. 485. For example, deception criterion has been excluded by the originator of this criterion in their later studies (Tao et al., Citation2010) and also by other researchers (e.g., King & Delfabbro, Citation2013; Ko et al., Citation2014). Also, many authors questioned the validity of the Internet gaming disorder construct itself (King & Delfabbro, Citation2014). Moreover, SMD scale is a diagnostic tool and the respondents have to answer in a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ format. There is evidence that multiple-choice items yielded a more reliable scores than obtained from dichotomous items (Haladyna, Citation1992). Further, Pontes et al. (Citation2014) also pointed out the statistical issues in restrictive ‘yes’ or ‘no’ format. Moreover, clinical diagnosis of any problem including SMD has many advantages (Kuss et al., Citation2017), but only when the diagnostic criteria are well established. However, same cannot be said for IGD (Kuss et al., Citation2017; King & Delfabbro, Citation2014) and therefore SMD scale should only be used carefully. Thus, despite the promise of SMD scale to be a diagnostic tool to identify social media disorder especially among adolescents and young adults, this scale also suffers from many conceptual and methodological problems, thus, should not be used, else it will do more harm than solving any.

As mentioned above there are three other scales to measure SNS addiction. Addictive tendencies toward SNS is based on Young internet addiction test and has 20 items. Social networking website addiction scale is based on Charlton and Danforth (Citation2007) online gaming addiction and has 5 items. Shahnawaz et al. (Citation2013) scale is atheoretical in nature and used only rudimentary analysis. The tool used only exploratory factor analysis and tools based on only EFA are not robust enough (Hair et al., Citation2014). It is evident that all of the SNS addiction scales have used different framework or no framework at all to conceive the construct and development of items. BSMAS is based on behavioral addiction theory, but by using single item measure for the six components, it will fail to tap the nuances of social networking addiction. Also, Griffiths et al. (Citation2014) raised this concern and concluded that SNS addiction research suffers from a variety of methodological problems.

To overcome these conceptual and methodological concerns, the present study has aimed to develop a psychometrically sound tool to measure social networking addictions following behavioral addiction model (Griffiths, Citation2005). Three different studies have been conducted to achieve the study’s aim. These three studies aimed at (1) establishing the construct validity of the SNAS, (2) assessing the test–retest reliability of the scale, and lastly, (3) establishing the convergent and divergent validity of SNAS.

5. Study 1 (Construct validity)

The scale was constructed based on the six components of behavioral addiction specified by Griffiths (Citation2005). Initially, 30 items, 5 for each components were written. Five researchers examined the content validity of these items and they advised to drop six items as they seemed to be repetitive or not tapping the intended construct. Finally, 24 items were retained with 4 items for each of the components. To test the factor structure of the construct, questionnaires were sent to 650 participants ; 570 questionnaires were returned with 45 questionnaires being incomplete, thus there were 525 usable questionnaires. There were a total of 128 males, 378 females, and 19 participants did not disclose their sex. The mean age of the sample was 20.4. Prior data collection, written consent was obtained from all the participants. There were a total of 42 missing values in all the responses, which were replaced by the series mean. The data analysis was done with the help of SPSS AMOS version 21.

6. Results

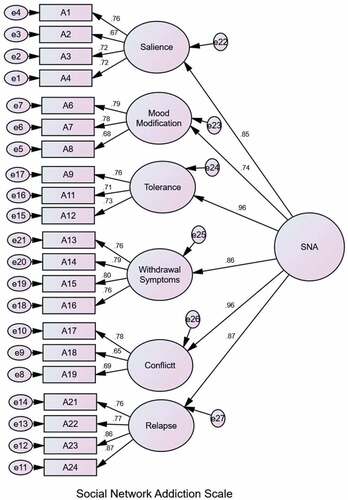

CFA was run on all the 24 items loaded on 6 of the components of behavioral addiction, however, the fit indices were not great (Hair et al., Citation2014). CMIN/DF = 3.85, GFI = .88, CFI = .90, TLI = .89, RMSEA = .07, and SRMR = .05. Three items were deleted one by one to reach to an acceptable model fit. The items which were deleted during the analysis were (Item no 5—“Social networking makes me happy,” Item no 20—“I ignore my family/friends to be on social networking sites,” Item no 10—When I am on social networking sites, I lose track of time”). The deleted items were from Mood modification, Conflict and Tolerance dimension, respectively. The final scale of 21 items yielded an acceptable model fit index. The indices are CMIN/DF = 3.71, CFI = .93, TLI = .91, GFI = .90, RMSEA = .07, and SRMR = .04.

It is always advisable to test the competing models in order to test the validity of the obtained model (Garson, Citation2015). All the 21 items were loaded on single factor as being done in the BFAS (Andreassen et al., Citation2012b) and BSMAS (Andreassen et al., Citation2016). However, the model fit indices were far below than the recommended values given by Hair et al. (Citation2014). The indices were CMIN/DF = 7.89, GFI = .78, CFI = .81, TLI = .79, RMSEA = .11, and SRMR = .06. The results clearly indicated that social networking addiction is a six-dimensional construct instead of unidimensional, as being conceived by some of the earlier authors. Construct validity of SNAS was assessed by obtaining the factor loadings of each item on their respective latent construct as well as calculating average variance explained (AVE). The AVE for all the factors were found be more than .50 suggesting appropriate convergent validity. Composite reliabilities for all the six factors (Table ) as suggested by Hair et al. (Citation2014) were also obtained. The compositive reliability was found to be more than .70 for every factor suggesting appropriate reliability.

Table 1. (Showing factor loading, AVE and Composite reliability)

It was further hypothesized that social networking addiction would be a higher-order construct comprising of six first-level factors. We tested the same statistically and the model fit indices suggested an acceptable model fit. The model fit indices for the social networking addiction as a second order construct are CMIN/DF = 3.87, GFI = .90, CFI = .92, TLI = .91, RMSEA = .07, and SRMR = .04. The results provided evidence that social networking is a second-order construct comprising of six first-level factors. The model is presented in Figure . Further, a summary of statistics of all models are presented in Table

Table 2. Showing model fit statistics of all models

7. Study 2

The study was conducted to assess the test–retest reliability of the newly developed 21 item social networking scale. Those participants who had accepted to participate again and shared their phone numbers and email addresses during the study 1 were contacted. Seventy-eight participants willingly made themselves available for this study. The time gap between the two points was 25 days.

8. Results

The test–retest reliability was found to be .88 which confirms that the newly developed scale is a reliable measure of social network addiction.

9. Study 3

Construct validation is incomplete without testing for convergent and divergent validity of the construct. According to Campbell and Fiske (Citation1959), a scale is said to possess convergent validity when it is found to be positively associated with other scales of the similar nature. Similarly, the discriminant validity of a construct is said to be supported when it is found to be negatively or poorly associated with dissimilar constructs. To assess the convergent and divergent validity of SNAS, problematic internet use, facebook addiction, average time spent online, loneliness, and life satisfaction constructs were used. Presented below is a brief description of these constructs and the hypotheses tested in study 3.

9.1. Problematic internet usage

Problematic internet use has been construed as a set of cognitive, affective and behavioral symptoms which hampers one’s functioning outside of the cyberspace in the real world (Caplan et al., Citation2009). While problematic internet usage is generic in nature, social networking is one of the usages of internet. Thus, we hypothesized that:

H1: There would be a significant positive correlation between problematic internet use and social networking addiction.

9.2. Facebook addiction

Among many social networking platforms, Facebook has the maximum number of active users (Statista, Citation2017). Facebook addiction is just one of the various social networking platforms available to the users. Thus, it is proposed that:

H2: There would be a significant positive correlation between Facebook addiction and social networking addiction.

9.3. Average time spent online

Social networking sites can be accessed on computers, laptops, and even on smartphones. One needs to invest time in order to use them. According to a report by Wallace (Citation2015), teens spend 9 hours a day on social media. Other reports claim that users of age group 15–19 spend at least 3 hours a day on social media (Sethi, Citation2015). There was a significant relationship between going to bed and getting up late with Facebook addiction (Andreassen et al., Citation2012b). It is therefore hypothesized:

H3: There would be a significant positive relationship between SNAS and Average time spent on social networking

9.4. Loneliness

Ever since the launch of social networking sites, its primary goal is to let people connect with their friends and family. However, with time, social networking has replaced the way people interact with each other. There is evidence to suggest that adolescents use social networking very frequently. As per Kaiser family foundation (Citation2010), 8–18 years old spend more than 7 hours every day on social media . Molloy (Citation2017) found that excessive use of social media increases loneliness and envy. According to Hosie (Citation2017), people who log in to social networking sites more than 58 times a week are three times lonelier than people who don’t. Taking the inferences from the available literature, it is hypothesized that:

H4: There would be a significant positive relationship between Social networking scale and loneliness.

9.5. Life Satisfaction

Life satisfaction is one’s subjective evaluation of one’s life. Frunzaru and Boțan (Citation2015) concluded social networking websites make users materialistic, which in turn makes them less satisfied with life. Longstreet and Brooks (Citation2017) found negative correlation between life satisfaction and social media usage. Oh et al. (Citation2014) found dissatisfied people tend to use more online social networking. Błachnio et al. (Citation2016) found Facebook addiction negatively associated with life satisfaction. It is thus hypothesized:

H5: There would be a significant negative relationship between social networking addiction and satisfaction with life

10. Method

10.1. Sample

A total of 334 participants gave their written consent to participate in the current study; out of whom 70 were males, 261 were females, and 3 chose not to disclose their sex. All the participants were briefed about the study. The age range was found to be from 17 to 25 and mean age was found to be 20.33 with 1.7 standard deviations. Convenience sampling procedure was used to reach the participants. The data was collected from participants living in and around Delhi NCR, India.

11. Measures

All the questionnaires used in the study have been used in their original language “English”. The participants were proficient enough to understand English, as English was their second language.

11.1. Problematic internet usage

Online Cognition Scale (Davis et al., Citation2002) is a measure of problematic internet use. The 36 item scale measures cognition about problematic internet use by 7-point Likert scale wherein, respondents express the extent of their agreement or disagreement with the scale items. The Cronbach’s alpha in the present study was found to be .93.

11.2. Facebook addiction

Bergen Facebook Addiction Scale (Andreassen et al., Citation2012b) was used to assess Facebook addiction. It is six-item scale, wherein, respondents were asked to respond on a 7-point Likert scale. The Cronbach’s alpha in the present study was found to be .84.

11.3. Average time spent on social networking sites

Averaage time spent was assessed with the help of a single question, wherein, respondents had to answer about approximate time they spend on social networking every day. In the present study, the average time spent on the social networking was found to be 3.02 hours with 1 hour being the minimum and 12 being the maximum.

11.4. Loneliness

A 3 items scale by Hughes et al. (Citation2004) was used to assess loneliness. The scale was developed from UCLA Loneliness scale (R-UCLA) (Russell et al., Citation1980). The responses were captured on a 7-point rating scale, where 1 meant 'Never' and 7 was for 'Every time'. The Cronbach’s alpha in the present study was found to be .85

11.5. Satisfaction with life

Satisfaction with life scale (Diener et al., Citation1985) is a five-item scale developed to assess one’s cognitive judgment about life. The respondents chose a best possible response from 1 to 7, where 1 meant 'Strongly disagree', while 7 meant 'Strongly agree'. The Cronbach’s alpha in the present study was found to be .70

12. Results

The descriptive are shown in Table . The mean score SNAS was found to be 70.94 with 23.53 standard deviation. The mean score for OCS and FAS was found to be 117.60 and 13.41 with 32.72 and 6.79 standard deviations, respectively. The mean score of loneliness and life satisfaction were found to be 10.39 and 20.99 with 4.02 and 7.06 standard deviations, respectively.

Table 4. Showing correlation between the variable

Table 3. Showing descriptive statistics

The results of correlational analysis as shown in Table , suggest that SNAS is positively correlated with both problematic internet and social networking usage. Correlation coefficient (r = .73, p < .01) shows a positive significant correlation between social networking and problematic internet usage. Social networking addiction also shared a significant positive correlation (r = .50, p < .01) with facebook addiction. Correlation coefficient (r = .38, p < .01) shows a significant positive correlation between snas and average time spent online. The relationship between loneliness and snas was found to be significant and positive (r = .23, p < .01). A significant negative relationship was found between SNAS and life satisfaction (r = −.15, p < .01). Interestingly, all the three measures of addiction, SNAS, BFAS, and OCS shared similar kind of relationship with the remaining three variables such as average time spent on social networking, loneliness, and life satisfaction.

13. Discussion

There is a growing body of literature along with increasing public concern around social networking addiction. However, in the absence of a psychometrically sound tool based on suitable theory, the subject of social networking suffers from many conceptual and methodological problems. In the current paper, three studies were conducted to develop a theoretically and psychometrically sound tool to assess social networking addiction. The results of the current study revealed that social networking addiction is a higher-order construct having six first-order dimensions. However, many times the scores on each of the six components may provide some useful information, as addiction is not an either-or phenomenon (Young, Citation1998). Addiction can be manifested in different ways for different individuals (Davazdahemami et al., Citation2016) and therefore can be considered on a spectrum with varying levels of severity (Soror et al., Citation2015). This is unlike BSMAS in which we can only get an overall score and there is evidence that all the components of behavioral addiction may not be present in the concerned people (Jameel et al., Citation2019). Therefore, scores on each of the dimensions as well as total social networking addiction score appear to be the best way out and may be called as social networking addiction profile.

The high test–retest reliability showed that the social networking addiction is relatively stable in nature and proper intervention is needed to help SNSs addicts, as being done in other behavioral disorders such as alcohol or sex or gambling or study addiction (Atroszko et al., Citation2016). Interestingly, the value of 0.88 is quite similar to the test–retest reliability of 0.82 which was obtained for BFAS (Andreassen et al., Citation2012b). This further provides support for the relative stability of social networking addictions and this has implication for therapists and counselors.

The newly developed scale (Social networking addiction scale) showed strong correlation with Online cognition scale and Bergen facebook addiction scale. All the three scales tend to measure similar constructs. While, OCS measures problematic internet usage, BFAS assess Facebook addiction. Thus, internet addiction is generic/broad, while Facebook addiction is very narrow/specific and social networking addiction fits between these two different forms of behavioral addiction. The results are interesting as SNAS shares 53% of the variance with OCS (r = .73, p < .01) and 25% with BFAS (r = .50, p < .01) indicating that SNAS is one of the applications of internet. Therefore, it shares half of the variance with generic internet while remaining half is unique to social networking. There is evidence that social networking is one of the important reasons because of which youngsters use internet (Raju et al., Citation2015). On the other hand, Facebook is just one of the social networking applications, thus SNAS shares 25% variance with BFAS while 75% remains unique to SNAS as people might use other forms of social networking such as Whatsapp, Instagram, Snapchat, Twitter, etc. Also there is enough evidence to suggest that Facebook is a small subset of social networking addiction (Donnelly & Kuss, Citation2016; Kuss & Griffiths, Citation2017). This places SNAS as a unique tool which is situated between both the generic internet problematic use and specific Facebook addiction. Being an umbrella, social networking addiction scale has the capacity to assess addiction to all kinds of social networking websites and applications such as Facebook, WhatsApp, Instagram, etc.

As mentioned earlier, that being “online” is the new norm for many of the youngsters and most of us live internet mediated lives (Kuss & Griffiths, Citation2017). The results showed that there was a significant positive correlation between SNAs and average time spent online. McGrath (Citation2016) stated that social networking takes one-third of the time spent online. Sponcil and Gitimu (Citation2013) found that 59.4% of college going students use social networking sites many times in a day. Tang and Koh (Citation2017) found that 29.5% of the Singapore college students are addicted to social networking. Not only SNAS, internet addiction, and Facebook addiction also showed a significant positive correlations with average time spent online. However, the relationship was far stronger for SNAS compared to the other two, indicating that social networking is one of the main reasons because of which youngsters use the internet (Andreassen, Citation2015; Andreassen et al., Citation2013; Turel & Serenko, Citation2012).

There is a significant positive correlation between SNAS and loneliness and a significant negative correlation between SNAS and Life Satisfaction. It shows that even if social networking helps people to stay in touch with each other, they remain isolated and lonely (Turkle, Citation2013, Citation2015). As a result, they feel lonely and are less satisfied with their lives and there is existing empirical evidence for this (Frunzaru & Boțan, Citation2015; Longstreet & Brooks, Citation2017). Lastly, Sabatini and Sarracino (Citation2017) also found that the use of social networking has a negative impact on the wellbeing.

14. Conclusion and limitations

The three studies were conducted to develop a theoretically and psychometrically sound tool to assess social network addiction. This tool is unique because it is neither generic to measure internet addiction or social media addiction nor it is specific to measure Facebook addiction. Also, SNAS can be used to measure addiction of all forms of social networking such as Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp or Twitter. SNAS has also been found to be higher order construct, so we can obtain just one score to identify vulnerable section of adolescents, however, dimension wise score could provide possibility for better intervention. The scale showed a good test–retest reliability over a period of 25 days which implies that once addicted, people would remain so for some time and intervention is required to help them. In addition, the convergent and divergent validity of the scale were also established.

Although the scale is a theoretical and psychometrically sound measure, it also has some limitations. The scale is validated on Indian students primarily from Northern part of India. Therefore, the scale needs to be validated in other parts of the country and also in other cultural contexts. There is enough evidence that different sections of people use social networking sites differently, hence, future researchers can compare people from different backgrounds (such as students, professionals, etc.) to provide additional construct validity evidence.

correction

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Mohammad Imran, Nanaki J. Chadha and Kavita Assi for their valuable inputs.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Usama Rehman

Prof Mohammad Ghazi Shahnawaz teaches Psychology at the Department of Psychology, Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi, India. He has over 25 years of teaching and research experience. His Ph.D. thesis was in the area of Industrial and Organizational Psychology. He has worked on dark triads of personality in the organizational context. He has also explored modern technologies such as smartphones, social media and how our life has been impacted by these. Currently, he is pursuing research in the area of COVID-19 and its varied manifestations in people’s lives.

Dr. Usama Rehman is currently serving as an Assistant professor at the Department of Psychology, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh, India. He completed his Ph.D. from the Dept. of Psychology, Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi, India. He has keen interest in applied social psychology.

References

- Andreassen, C. (2015). Online social network site addiction: A comprehensive review. Current Addiction Reports, 2(2), 175–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-015-0056-9

- Andreassen, C., Billieux, J., Griffiths, M., Kuss, D., Demetrovics, Z., Mazzoni, E., & Pallesen, S. (2016). The relationship between addictive use of social media and video games and symptoms of psychiatric disorders: A large-scale cross-sectional study. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 30(2), 252–262. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000160

- Andreassen, C., Griffiths, M., Gjertsen, S., Krossbakken, E., Kvam, S., & Pallesen, S. (2013). The relationships between behavioral addictions and the five-factor model of personality. Journal Of Behavioral Addictions, 2(2), 90–99. https://doi.org/10.1556/jba.2.2013.003

- Andreassen, C., Griffiths, M., Hetland, J., & Pallesen, S. (2012a). Development of a work addiction scale. Scandinavian Journal Of Psychology, 53(3), 265–272. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9450.2012.00947.x

- Andreassen, C. S., Torsheim, T., Brunborg, G. S., & Pallesen, S. (2012b). Development of a Facebook Addiction Scale. Psychological Reports, 110(2), 501–517. https://doi.org/10.2466/02.09.18.pr0.110.2.501-517

- Armstrong, L., Phillips, J., & Saling, L. (2000). Potential determinants of heavier internet usage. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 53(4), 537–550. https://doi.org/10.1006/ijhc.2000.0400

- Atroszko, P., Andreassen, C., Griffiths, M., & Pallesen, S. (2016). The relationship between study addiction and work addiction: A cross-cultural longitudinal study. Journal Of Behavioral Addictions, 5(4), 708–714. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.5.2016.076

- Bányai, F., Zsila, Á., Király, O., Maraz, A., Elekes, Z., Griffiths, M., Andreassen, C. S., & Demetrovics, Z. (2017). Problematic social media use: Results from a large-scale nationally representative adolescent sample. Plos One, 12(1), e0169839. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0169839

- Bergkvist, L., & Rossiter, J. (2007). The predictive validity of multiple-item versus single-item measures of the same constructs. Journal Of Marketing Research, 44(2), 175–184. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.44.2.175

- Billieux, J., Maurage, P., Lopez-Fernandez, O., Kuss, D., & Griffiths, M. (2015). Can disordered mobile phone use be considered a behavioral addiction? An update on current evidence and a comprehensive model for future research. Current Addiction Reports, 2(2), 156–162. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-015-0054-y

- Błachnio, A., Przepiorka, A., & Pantic, I. (2016). Association between Facebook addiction, self-esteem and life satisfaction: A cross-sectional study. Computers In Human Behavior, 55, Part B 701–705. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.10.026

- Çam, E., & Isbulan, O. (2012). A new addiction for teacher candidates: Social networks. Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology-TOJET, 11(3), 14–19. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ989195

- Campbell, D. T., & Fiske, D. W. (1959). Convergent and discriminant validation by the multitrait-multimethod matrix. Psychological Bulletin, 56(2), 81. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0046016

- Caplan, S., Williams, D., & Yee, N. (2009). Problematic Internet use and psychosocial well-being among MMO players. Computers in Human Behavior, 25(6), 1312–1319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2009.06.006

- Carbonell, X., Chamarro, A., Griffiths, M., & Talarn, A. (2012). Uso problemático de Internet y móvil en adolescentes y jóvenes españoles. Anales de Psicología, 28(3), 3. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.28.3.156061

- Cerniglia, L., Guicciardi, M., Sinatra, M., Monacis, L., Simonelli, A., & Cimino, S. The use of digital technologies, impulsivity and psychopathological symptoms in adolescence. (2019). Behavioral Sciences, 9(8), 82. art. no. 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs9080082

- Charlton, J. P., & Danforth, I. D. (2007). Distinguishing addiction and high engagement in the context of online game playing. Computers in Human Behavior, 23(3), 1531–1548. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2005.07.002

- Clark, M., & Calleja, K. (2008). Shopping addiction: A preliminary investigation among Maltese university students. Addiction Research & Theory, 16(6), 633–649. https://doi.org/10.1080/16066350801890050

- Davazdahemami, B., Hammer, B., & Soror, A. (2016). Addiction to mobile phone or addiction through mobile phone?. In 2016 49th Hawaii international conference on system Sciences (HICSS) (pp. 1467e1476). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/HICSS.2016.186

- Davies, T., & Cranston, P. (2008). Youth work and social networking: Interim report. National Youth Agency.

- Davis, R. A., Flett, G. L., & Besser, A. (2002). Validation of a new scale for measuring problematic Internet use: Implications for pre-employment screening. CyberPsychology& Behavior, 5(4), 331–345. https://doi.org/10.1089/109493102760275581

- Diamantopoulos, A., Sarstedt, M., Fuchs, C., Wilczynski, P., & Kaiser, S. (2012). Guidelines for choosing between multi-item and single-item scales for construct measurement: A predictive validity perspective. Journal Of The Academy Of Marketing Science, 40(3), 434–449. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-011-0300-3

- Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The Satisfaction with LifeScale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

- Donnelly, E., & Kuss, D. (2016). Depression among users of social networking sites (SNSs): The role of SNS addiction and increased usage. Journal Of Addiction And Preventive Medicine, 2(1). https://doi.org/10.19104/japm.2016.107

- Frunzaru, V., & Boțan, M. (2015). Social networking websites usage and life satisfaction: A study of materialist values shared by Facebook users. Romanian Journal Of Communication And Public Relations, 17(2), 43. https://doi.org/10.21018/rjcpr.2015.2.24

- Gardner, D., Cummings, L., Dunham, R., & Pierce, J. (1998). Single-item versus multiple-item measurement scales: An empirical comparison. Educational And Psychological Measurement, 58(6), 898–915. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164498058006003

- Garson, G. D. (2015). Structural equation modeling. Statistical Associates Publishers.

- Global social media ranking 2017. Statistic. (2017, December 25). Statista. Retrived from https://www.statista.com/statistics/272014/global-social-networks-ranked-by-number-of-users

- Griffiths, M. (2005). A ‘components’ model of addiction within a biopsychosocial framework. Journal Of Substance Use, 10(4), 191–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/14659890500114359

- Griffiths, M. D., Kuss, D. J., & Demetrovics, Z. (2014). Social networking addiction: An overview of preliminary findings. In Behavioral addictions (1st ed., pp. 119–141). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-407724-9.00006-9: Academic Press.

- Hair, J., Black, W., Babin, B., & Anderson, R. (2014). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Pearson Education Limited.

- Haladyna, T. (1992). The effectiveness of several multiple-choice formats. Applied Measurement In Education, 5(1), 73–88. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15324818ame0501_6

- Hosie, R. (2017, December 29). The longer you spend on social networks, the lonelier you’re likely to be. The Independent. http://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/social-media-high-usage-more-isolated-lonely-people-study-university-pittsburgh-a7614226.html

- Hughes, M. E., Waite, L. J., Hawkley, L. C., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2004). A short scale for measuring loneliness in large surveys. Research on Aging, 26(6), 655–672. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027504268574

- Jameel, S., Shahnawaz, M. G., & Griffiths, M. D. (2019). Smartphone addiction in students: A qualitative examination of the components model of addiction using face-to-face interviews. Journal of Behavioural Addiction, 8(4), 780–793. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.8.2019.57

- Kaiser Family Foundation. (2010). Generation M2: Media in the Lives of 8- to 18-Year-Olds. Retrieved from https://www.kff.org/other/event/generation-m2-media-in-the-lives-of/

- Kaplan, A., & Haenlein, M. (2010). Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of Social Media. Business Horizons, 53(1), 59–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2009.09.003

- Kaplan, R. M., & Saccuzzo, D. P. (2018). Psychological testing: Principles, applications, & issues. Cengage Learning.

- Kardefelt-Winther, D., Heeren, A., Schimmenti, A., van Rooij, A., Maurage, P., Carras, M., Edman, J., Blaszczynski, A., Khazaal, Y., & Billieux, J. (2017). How can we conceptualize behavioural addiction without pathologizing common behaviours? Addiction, 112(10), 1709–1715. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13763

- King, D., & Delfabbro, P. (2013). Video-gaming disorder and the DSM-5: Some further thoughts. Australian & New Zealand Journal Of Psychiatry, 47(9), 875–876. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867413495925

- King, D., & Delfabbro, P. (2014). The cognitive psychology of Internet gaming disorder. Clinical Psychology Review, 34(4), 298–308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2014.03.006

- Ko, C., Yen, J., Chen, S., Wang, P., Chen, C., & Yen, C. (2014). Evaluation of the diagnostic criteria of Internet gaming disorder in the DSM-5 among young adults in Taiwan. Journal Of Psychiatric Research, 53, 103–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.02.008

- Kuss, D., & Griffiths, M. (2011). Online social networking and addiction—a review of the psychological literature. International Journal Of Environmental Research And Public Health, 8(12), 3528–3552. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph8093528

- Kuss, D., & Griffiths, M. (2017). Social networking sites and addiction: Ten lessons learned. International Journal Of Environmental Research And Public Health, 14(3), 311. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14030311

- Kuss, D., Griffiths, M., & Binder, J. (2013). Internet addiction in students: Prevalence and risk factors. Computers In Human Behavior, 29(3), 959–966. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.12.024

- Kuss, D. J., Griffiths, M. D., & Pontes, H. M. (2017). Chaos and confusion in DSM-5 diagnosis of Internet Gaming Disorder: Issues, concerns and recommendations for clarity in the field. Journal of Behavioral Addiction, 6(2), 103–109. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.5.2016.062

- Lin, C., Broström, A., Nilsen, P., Griffiths, M., & Pakpour, A. (2017). Psychometric validation of the Persian Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale using classic test theory and Rasch models. Journal Of Behavioral Addictions, 6(4), 620–629. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.6.2017.071

- Longstreet, P., & Brooks, S. (2017). Life satisfaction: A key to managing internet & social media addiction. Technology In Society, 50, 73–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2017.05.003

- McGrath, F. (2016). Social networks grab a third of time spent online. GlobalWebIndex Blog. Retrieved January 17, 2018, from https://blog.globalwebindex.net/chart-of-the-day/social-networks-grab-a-third-of-time-spent-online/

- Molloy, M. (2017, December 29). Too much social media ‘increases loneliness and envy’ - study. The Telegraph. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/technology/2017/03/06/much-social-media-increases-loneliness-envy-study/

- Monacis, L., de Palo, V., Griffiths, M., & Sinatra, M. (2017). Social networking addiction, attachment style, and validation of the Italian version of the Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale. Journal Of Behavioral Addictions, 6(2), 178–186. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.6.2017.023

- Monacis, L., De Palo, V., Griffiths, M. D., & Sinatra, M. (2016). Validation of the Internet Gaming Disorder Scale - Short-Form (IGDS9-SF) in an Italian-speaking sample. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 5(4), 683–690. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.5.2016.083

- Monacis, L., Griffiths, M. D., Limone, P., Sinatra, M., & Servidio, R. (2020). Selfitis behavior: Assessing the Italian version of the selfitis behavior scale and its mediating role in the relationship of dark traits with social media addiction. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17 (16), 1–17. art. no. 5738. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17165738

- Morahan-Martin, J., & Schumacher, P. (2000). Incidence and correlates of pathological Internet use among college students. Computers in Human Behavior, 16(1), 13–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0747-5632(99)00049-7

- Nunnally, J. C. (1978). Psychometric theory. McGraw-Hill.

- Oh, H. J., Ozkaya, E., & Larose, R. (2014). How does online social networking enhance life satisfaction? The relationships among online supportive interaction, affect, perceived socialsupport, sense of community, and life satisfaction. Computers in Human Behavior, 30, 69–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.07.053

- Pontes, H. M., Kiraly, O., Demetrovics, Z., & Griffiths, M. D. (2014). The conceptualization and measurement of DSM-5 Internet Gaming Disorder: The development of IGD-20 Test. PLoS ONE, 9(10), e110137. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0110137

- Raju, N. J., Valsaraj, B. P., & Noronha, J. (2015). Online social networking: Usage in adolescents. Journal of Education and Practice, 6(22), 80–84. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1079507

- Regina, J. J. M., Ejinden, V. D., Lemmens, J. S., & Valkenburg, P. M. (2016). The social media disorder scale: Validity and psychometric properties. Computers in Human Behavior, 61, 478–487. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.03.038

- Rossiter, J. (2002). The C-OAR-SE procedure for scale development in marketing. International Journal Of Research In Marketing, 19(4), 305–335. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-8116(02)00097-6

- Russell, D., Peplau, L. A., & Cutrona, C. E. (1980). The revised UCLA Loneliness Scale: Concurrent and discriminant validity evidence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39(3), 472–480. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.39.3.472

- Sabatini, F., & Sarracino, F. (2017). Online networks and subjective well-being. Kyklos, 70(3), 456–480. https://doi.org/10.1111/kykl.12145

- Scarepello, V., & Campbell, J. (1983). Job satisfaction: Are all parts there? Personnel Psychology, 36(3), 577–600. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1983.tb02236.x

- Sethi, L. (2015). Social media addiction: 39,757 years of time is spend everyday. Dazeinfo. Retrieved December 29, 2017, from https://dazeinfo.com/2015/01/12/social-media-addiction/

- Shahnawaz, M. G., Ganguli, N., & Zou, M. Z. (2013). Social Networking Addiction Scale. Prasad Psycho Corporation.

- Smith, A., & Anderson, M. (2018, August 24). Social media use 2018: Demographics and statistics. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewinternet.org/2018/03/01/social-media-use-in–2018/

- Sofiah, S. Z., Omar, S. Z., Bolong, J., & Osman, M. N. (2011). Facebook addiction among female university students. Revista de Adminstratie si Politici Sociale (The Public Adminstration and Social Policies Revies), 2(7), 95–109. Retrieved August 25, 2018, from http://www.uvvg.ro/revad/files/nr7/10.%20sharifah.pdf

- Soror, A., Hammer, B., Steelman, Z., Davis, F., & Limayem, M. (2015). Good habits gone bad: Explaining negative consequences associated with the use of mobile phones from a dual-systems perspective. Information Systems Journal, 25(4), 403–427. https://doi.org/10.1111/isj.12065

- Sponcil, M., & Gitimu, P. (2013). Use of social media by college students: Relationship to communication and self-concept. Journal of Technology Research, 4, 1–13. http://www.aabri.com/manuscripts/121214.pdf

- Sussman, S., Leventhal, A., Bluthenthal, R., Freimuth, M., Forster, M., & Ames, S. (2011). A Framework for the Specificity of Addictions. International Journal Of Environmental Research And Public Health, 8(12), 3399–3415. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph8083399

- Tang, C. S., & Koh, Y. Y. (2017). Online social networking addiction among college students in Singapore: Comorbidity with behavioral addiction and affective disorder. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 25, 175–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2016.10.027

- Tao, R., Huang, X., Wang, J., Zhang, H., Zhang, Y., & Li, M. (2010). Proposed diagnostic criteria for internet addiction. Addiction, 105(3), 556–564. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02828.x

- Turel, O., & Serenko, A. (2012). The benefits and dangers of enjoyment with social networking websites. European Journal Of Information Systems, 21(5), 512–528. https://doi.org/10.1057/ejis.2012.1

- Turkle, S. (2013). Alone together. Why we expect more from technology and less from each other. Basic Books.

- Turkle, S. (2015). Reclaiming conversation: The power of talk in a digital age. Penguin.

- van den Eijnden, R., Lemmens, J., & Valkenburg, P. (2016). The social media disorder scale. Computers In Human Behavior, 61, 478–487. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.03.038

- Wallace, K. (2015). Teens spend 9 hours a day using media, report says - CNN. CNN. Retrieved December 29, 2017, from http://edition.cnn.com/2015/11/03/health/teens-tweens-media-screen-use-report/index.html

- Wanous, J., Reichers, A., & Hudy, M. (1997). Overall job satisfaction: How good are single-item measures? Journal Of Applied Psychology, 82(2), 247–252. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.82.2.247

- Wu, A., Cheung, V., Ku, L., & Hung, E. (2013). Psychological risk factors of addiction to social networking sites among Chinese smartphone users. Journal Of Behavioral Addictions, 2(3), 160–166. https://doi.org/10.1556/jba.2.2013.0s

- Young, K. S. (1998). Internet addiction: The emergence of a new clinical disorder. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 1(3), 237–244. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.1998.1.237