Abstract

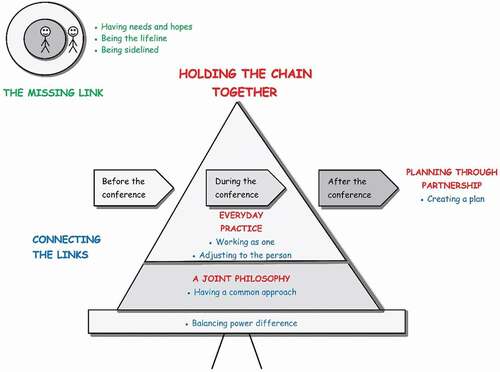

Abstract: The integration of healthcare and social services has made collaborative care plans an important tool for health and social care professionals and the person involved. The collaborative planning process is challenging, and studies have revealed that its implementation and outcomes are not satisfactory for all participants. The study aimed to explore the collaborative planning process and attributes contributing to making the process work for all participants. The study focused on older adults in need of a collaborative care plan and adopted a grounded theory approach. Several sources were used to collect data from participants. The findings revealed an overarching process and two sub-processes. The overarching process “holding the links together” described the identified core attributes, joint philosophy, everyday practice and planning through partnership. The two sub-processes, “the missing link” and “connecting the links”, described the participants’ perspectives. The conceptual model explained the identified attributes and the connections between the overarching process and the two sub-processes. The study confirmed the complexity of collaboration between actors, professionals, older adults and informal caregivers. When one or more attribute did not function optimally or was missing, it affected the collaborative care planning process and participants involved, with consequences for the older adult. A joint philosophy, an ethic, could facilitate and guide professionals in everyday practice through all steps of the collaborative care planning process and contribute in making the process successful.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

When an older adult need assistant from health and social care there is a need to coordinate and plan the care and services provided. Studies have revealed that the collaborative care planning process is challenging and not satisfactory for the participants. In this study, we wanted to explore the collaborative care planning process and understand what attributes make it successful for the participants involved. The findings revealed that for the collaborative care planning to be successful the participants needed a joint philosophy an ethic to guide them in the everyday practice and that the care planning was done through a partnership. A model explained how the attributes and the participants perspectives were connected influenced each other and worked in synergy. When one or more attribute did not function optimally or was missing, it affected the collaborative care planning process and participants involved, with consequences for the older adult.

1. Introduction

Population aging, increase in chronic illness and rising demands for care make it difficult for the existing health and social care systems to cope effectively (World Health Organization, Citation2015). As a reaction, several national governments have promoted integrated care or different forms of collaboration or coordination between health and social care (McCormack et al., Citation2015). Collaborative care planning for older adults is used for individuals with multiple chronic conditions in primary healthcare, community care or when patients are transferred from specialized care to primary healthcare or community care (Condelius et al., Citation2016; Gonçalves‐Bradley et al., Citation2016; Van Dongen, Jerôme Jean Jacques, Lenzen et al., Citation2016a). Research has shown that collaborative care planning and shared decision-making improve communication and care coordination (World Health Organization, Citation2018). Such care plan improves self-management and reduces unnecessary care (Burt et al., Citation2014; Menefee, Citation2014; Newbould et al., Citation2012). Further, personalized planning is a useful strategy to integrate the older adults’ perspective in the decision-making process (Van Dongen, Jerôme Jean Jacques, Lenzen et al., Citation2016a) and facilitate person-centred care (PCC). Involving the patient in the decision-making process is essential for achieving PCC (Ekman et al., Citation2011; Légaré et al., Citation2011). However, several studies (Bjerkan et al., Citation2011; Burt et al., Citation2014; Jansen et al., Citation2015; Newbould et al., Citation2012; Reeves et al., Citation2014; Shiner et al., Citation2018) show that collaborative care planning at primary healthcare clinics is meagre. There are many forces resistant to coordinated care due to the way health systems are funded, managed and delivered. Thus, it becomes difficult to coordinate and integrate activities of different organisations. Collaborative care planning is a complex process and a relatively new phenomenon. There is a need for more research to understand the complexity of the process and also how to make collaborative care planning successful for all the participants involved.

2. Background

In response to changing population needs in healthcare and social services, integrating health and social care has become part of healthcare policy in many countries (Timmins & Ham, Citation2013). Health and social care policies also emphasise person-centred principles and concepts (McCormack & Dewing, Citation2019). Co-creation of care between older adults, their informal caregivers and health and social care professionals is the core component of person-centred practice. However, participation is a complex, multi-layered and dynamic concept (Claassens et al., Citation2014). Studies have revealed that the collaborative planning process is unclear for the older adult (Jobe et al., Citation2018; Kristensson et al., Citation2018; Newbould et al., Citation2012; Rustad et al., Citation2016), and they and their informal caregivers’ possibility to participate in decision-making is limited (Berglund et al., Citation2012; Jobe et al., Citation2018; Kristensson et al., Citation2018). Few studies have focused on experiences and outcomes for the older adult or integrating the older adult as a partner in the care team. There is a need for more studies of persons’ experiences with collaborative care planning and what models work best (Coulter et al., Citation2015).

Studies have revealed that interprofessional teamwork is positively affected by the use of collaborative care plans (Van Dongen, Jerôme Jean Jacques, Lenzen et al., Citation2016a). However, professional culture and individuals’ lack of interprofessional knowledge (Asakawa et al., Citation2017), along with professional roles, boundaries and authority can make interprofessional teamwork challenging (Karam et al., Citation2018). Duner (Citation2013) showed that interprofessional teamwork in collaborative care planning was most noticeable in the assessment phase, lower in the planning phase and almost not-existent in the decision phase.

To improve healthcare services for frail older adults in Sweden, a number of reforms have been enacted at the national and regional level, focusing on trying to reduce hospital stays through preventive measures, improved community services and collaborative care plans (Anell & Glenngård, Citation2014). According to the law (SFS (Citation2017:612), :612), the region and municipality shall collaborate and establish a collaborative care plan for persons needing healthcare and social services. The collaborative care plan is a shared document that involves shared input from an interprofessional team of professionals working with the older adult. However, the collaborative care planning process is complex and despite legislation and directives, it is not functioning optimally. Research of person-centred collaborative care planning is limited. By exploring the collaborative care planning process and the participants’ experiences deeper knowledge will emerge and contribute to shed light on how to improve planning processes, and give health and social care professionals new strategies to use when implementing the collaborative care planning process, and integrating the older adult and their informal caregivers into the team.

This study aimed to explore the collaborative care planning process and attributes which contribute to making the process work for all participants. The research questions were:

•Why is the collaborative individual planning process not carried out in an optimal way?

•What attributes contribute to it being successful for all participants?

3. Method

3.1. Design

A qualitative explorative design with a grounded theory approach was used. Grounded theory is well suited for studying social processes (Glaser & Strauss, Citation1967). The study adopted Charmaz’s (Citation2014) constructivist grounded methodology. According to Charmaz (Citation2014), the constructivist method acknowledges subjectivity and the researcher’s involvement in constructing and interpreting data.

3.2. Sample and setting

A project took place in northern Sweden, the region of Norrbotten, between 2016–2018 to improve working methods, establish collaborative care planning in the person’s home after discharge from the hospital, strengthen the older adult’s role and make the collaborative care plan digitally available through a national e-health platform (Region Norrbotten, Citation2019). Data for the study was collected within the project.

Purposive sampling was used to select participants. Participants in the study were older adults living at home, above 65 years of age in need of a collaborative care plan, their informal caregivers, and health and social care professionals working for municipalities or the region. The management team for the project, with managers from different municipalities and the region implementing the project, was also included.

Three nurses and one occupational therapist from different municipalities assisted in finding older adult and informal caregiver participants for the study. They approached older adults and/or their informal caregivers in need of a collaborative care plan and gave them study information, and the researchers then contacted those who agreed to participate. Managers from two municipalities and three health clinics helped find the health and social care professional participants and informed the professionals about the study. The researchers then contacted those who agreed to participate. One researcher contacted the management team.

3.3. Data collection

Data was collected between December 2017 and March 2019. Data collection and analysis occurred concurrently (Charmaz, Citation2014). See for more information.

Table 1. Overview over data collection and informants in chronological order

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with older adults and informal caregiver participants before and after the collaborative care planning conferences. Pre-conference interviews focused on the reason for the conference and their expectations. After-conference interviews concentrated on their experiences with the conference and subsequent expectations. The collaborative care planning conferences were observed and recorded digitally, and the researcher took notes of non-verbal communication, e.g., tone of voice, facial expression, gestures etc.

Focus group discussion, which had a moderator and observer, was used to collect data from the management team. It is useful for exploring individuals’ knowledge and experiences and illuminating perspectives through debating (Kitzinger, Citation1995). The moderator initiated discussion by reading a vignette based on previous data collection, interviews with older adults and informal caregivers and observations of collaborative care planning conferences (see ). The participants were invited to discuss the topic. The discussion was vivid, and the moderator just had to ask probing questions to deepen the discussion. The observer took notes during the discussion.

The semi-structured interviews with health and social care professionals were all individual interviews except one that was dyadic. All interviews, except three conducted by telephone, were carried out face to face. The interviews focused on the professionals’ experiences with the collaborative care planning process, and the researcher asked their opinions of previous data collected from older adults, informal caregivers, managers and observations of collaborative care planning conferences.

During data collection, memos were written on emerging codes that helped inform the interviews’ direction as well as selection of the next informants. Memos play a crucial part in grounded theory and assist in analysing data and codes early in the research process (Charmaz, Citation2014). The decision to stop data collection was made when the emerging categories were full and no new data surfaced. The same principle was applied during data analysis.

3.4. Data analysis

Data analysis was a continuous process of comparison between findings and emerging codes, beginning from the time of data collection. The first author transcribed the interviews verbatim in Swedish, and notes taken during the conferences were incorporated in the transcripts. The transcripts were read several times to get an overall picture and become familiar with the data. The next stage of analysis included line-by-line open coding. The codes stayed close to the data and showed actions. The coding defined what was happening in the data (Charmaz, Citation2014). The open codes were labelled in English and grouped into clusters that related to each other. During focused coding, the labelled clusters were used when re-examining the transcripts to sharpen the analysis. Attention in the coding phase helped researchers dig into the data and interpret participants’ tacit meaning (Charmaz, Citation2014). According to Dahlgren et al. (Citation2007), the researcher should use his or her personal and professional knowledge, including tacit knowledge, in the research process. The first author coded the data and discussed emerging categories with the other researchers. In the final stage, categories were also discussed with a group of external researchers. During theoretical coding, three concepts were established: the missing link, connecting the links, and holding the chain together. The connection between the theoretical codes was examined. illustrates the coding process. A model capturing the collaborative care planning process and its core elements was constructed. Finally, the findings were compared with existing literature, as presented in the discussion.

Table 2. An illustration of the coding process

3.5. Ethical considerations

All participants received verbal and written information about the study, and the researchers collected participants’ informed consent. They were informed about their voluntary participation and right to withdraw at any time without further explanation. Descriptions of the participants have been restricted, and pseudonyms are used to protect participants’ anonymity. The focus group participants made a verbal commitment that topics discussed would remain within the group. The Ethical Regional Board, Umeå, Sweden, granted permission for the study, number (dnr 2016/397-31).

4. Results

The conceptual model generated () explains the identified attributes of the collaborative care planning process. The overarching process, which was named “holding the chain together”, comprised two sub-processes: a) the missing link and b) connecting the links. The sub-processes explained participants’ perspectives of the collaborative care planning process. The overarching process, “holding the chain together”, illustrated the core attributes of the collaborative care planning process and how the processes linked together. Collaborative care planning was more than just “the care plan”, the document generated at the conference; it included what happened before, during and after the conference. The processes were connected to each other, and when one or more attribute did not function optimally or was missing, it affected the collaborative care planning process and participants involved, or as one participant expressed:

“The process builds on everyone doing their part. The chain is not stronger than its weakest link, so if one part is not working it will affect and have consequences for the whole process”. (Social worker manager)

4.1. Holding the chain together

This category comprised what were identified as the core attributes of the collaborative care planning process: a joint philosophy, everyday practice and planning through partnership. This was the end result of the two sub-processes and illuminated the core attributes needed to make the collaborative care planning process successful for participants.

4.1.1. A joint philosophy

The foundation of the collaborative care planning process were the values and attitudes participants had and practiced. The philosophy was interpreted to determine the process. It guided how the professionals planned, practiced and carried out the collaborative care planning process and the older adults’ and informal caregivers’ expectations and possibilities to partake. To hold the process together and make it successful for all participants, a common approach was needed, i.e. person-centred care, but also to define the principles and concepts within person-centred care in the same way. The health and social care professionals were responsible for defining and agreeing on a common approach, both within and between actors, and then as a team with each older person and informal caregiver.

4.1.2. Everyday practice

The philosophy was the starting point for the practice. To work in partnership, the different actors and health and social care professionals needed resources, strong leadership and support from their organization and other organizations. The professionals needed to assume responsibility and trust each other they also needed to include the older adult and informal caregiver in the partnership and collaborative care planning process. The philosophy needed to be ethical and visible in everyday practice, before, during and after the collaborative care planning conference. The health and social care professionals created an enabling environment so the older person and informal caregiver could participate in the process as partners, e.g., by adjusting to the older adult and utilize aids available to facilitate participation.

The power balance between participants affected the collaborative care planning process and the older adult’s ability to assume the role of the main actor and participate as a partner. It also affected how different actors and professionals worked together. The health and social care professionals needed to identify power differences and create an environment for reflection and discussion to learn from each other and internalize ethical practice.

4.1.3. Planning through partnership

Ideally, the older adult, informal caregiver, and health and social care professionals connected the links needed to form a chain, the collaborative care planning process. For the collaborative care planning process to succeed, participants needed to feel the value of planning together, and that the outcome, “the plan”, assisted them in their work and everyday life. If the chain did not hold together, and links were missing, it affected the collaborative care planning process and had consequences for the main actor, the older adult. The partnership needed to be visible and practiced at all stages, i.e. preparation, assessment, goal-setting, decision-making and follow-up.

4.2. The missing link

This sub-process comprised three properties: having needs and hopes, being the lifeline and being sidelined. It explained the older adults’ and informal caregivers’ experiences of the collaborative care planning process. They were the main actors, but were interpreted as the missing link when the professionals connected the different links in the collaborative care planning process to provide the best outcome for the patient.

4.2.1. Having needs and hopes

The older adults and informal caregivers had not noticed a new way of working. They lacked knowledge of the collaborative care planning process and the roles of different actors and professionals. For them, the focus was getting help with their needs and feeling safe. They wanted the health and social care professionals to acknowledge the older adult, his or her context and see the unique person. Further, they wished the professionals were more knowledgeable about them, their situations and interested in their life story.

“We want a collaborative care plan for the unique family or the unique person. Because you cannot compare my husband with the neighbour. Maybe from a medical point, but not the person. It is necessary to make that work”. (Wife, 67)

The older adults and informal caregivers questioned the organization and management of the healthcare and social services. They felt getting help was complicated and difficult, and they lacked flexibility. However, they were satisfied and content with the help and services they received. When they experienced good teamwork, they felt safe and thought the different competencies within the team complemented each other, but when the collaboration failed, they felt worried and frustrated. They desired a contact person or case manager they could turn to, someone who facilitated things related to the care and services they received.

4.2.2. Being the lifeline

A lifeline has two ends, and here it represented the informal caregivers’ dual role in providing daily care for the older adult targeted, handling all the practicalities and representing and giving voice to the older adult in contact with the healthcare and social services. They were also a resource for the health and social care professionals by facilitating their work and providing the possibility for the older adult to remain at home.

Being the lifeline included accepting the dual role and agreeing to the assistance and support provided by the healthcare and social services. Being together every day sometimes made it difficult for informal caregivers to determine their needs and the older adult’s needs. Older adults depended on the informal caregiver when they could not actively participate in the collaborative care planning process, and informal caregivers felt they had to take a huge responsibility for care and services, and often nothing happened if they did not take action.

“I do not want to take over the responsibility. I do not want to be his nurse, I am his wife, and the professionals need to take their responsibility”. (Wife, 77)

4.2.3. Being sidelined

The older adults received verbal and/or written information that a collaborative care planning conference would take place. However, they lacked knowledge of the purpose of collaborative care planning. Therefore, they had no expectations, and it affected their possibilities to prepare for the conference and prevented them from actively participating during the conference.

The older adults and informal caregivers preferred to meet in person. For persons with impairments, using telephone or video communication was difficult. During the collaborative care planning conference, informants reported not being listened to or health and social care professionals not understanding their problems. They thought many things were decided from the professionals’ viewpoint.

“I want to be in control. I want them to come to me and ask me to tell them and show them what I need help with and how I want things to be done. That is how I want it, but it is not happening. They do things the way they like it. If they wanted, it is possible, but they do not want, no”. (Man, 100)

They did not feel like partners or that they could influence the CIP process.

“I have been able to say what I want, but I have not been participating”. (Man, 70)

After the conference, the older adult or informal caregiver often forgot what had been decided, and they had not received the collaborative care plan or accessed it online. They considered the care plan and its content an essential part of the collaborative care planning process and relied on the professionals to carry out what had been agreed upon.

“Collaborative care planning is important. The care plan is the person’s document, and the ones working closest to the person need to know what they should do. Their job is the plan. The agreement we have of what will happen, how it will happen and who will do what, that is what is interesting in everyday life”. (Husband, 84)

4.3. Connecting the links

This sub-process comprised five properties: having a common approach, working as one, adjusting to the person, balancing power differences and planning together. It explains the health and social care professionals’ and managers’ experiences of the collaborative care planning process. Collaborative care planning is a complex process involving different laws, actors, professionals and older adults and their informal caregivers. Working together as partners in the planning process included connecting the different attributes to provide the best outcome for the patient.

4.3.1. Having a common approach

The health and social care professionals and managers from the healthcare and social services organizations said they worked according to a person-centred approach and saw the outcome of the collaborative care planning process, the care plan, as the person’s plan. Two main actors, the municipalities and the region, used different words for the approach, but management agreed with the definition. The approach involved having the person in focus, emphasizing participation, shared decision-making and supporting and strengthening the person’s capabilities. However, not all professionals carried out their work according to a person-centred approach. This became obvious during collaborative care planning conference observations. The managers recognized the challenges of working according to a person-centred approach and saw it as a learning process that would take time.

“To be able to work with a person-centred approach and with the individual as an equal partner in the process, we have to change our own focus and perspectives. It is a change of paradigm that is huge. We have to change the way we express ourselves and the way we document, and it is not an easy procedure, really difficult”. (OT manager)

4.3.2. Working as one

The region and municipalities had an overarching agreement related to collaborative care planning. However, individual workplaces and health and social care professionals lacked knowledge or interpreted the collaborative care planning process differently, which affected their work within the process. When professionals felt the way of working hindered a smooth process, it created dissatisfaction. Mainly professionals from the municipality were not content with some of the health clinics and their interpretation of what a home healthcare patient was. They felt the health clinics wanted to transfer work to them. There were also examples of ways of working that facilitated the process. One example was to delegate decision-making from one professional to another.

“The GP does not participate in the conference, but I can make decisions about how the medicines will be dispensed and if the individual will receive home healthcare or not”. (RN, Health Clinic)

Management had a crucial role in adjusting the organization to a person-centred approach, providing the resources needed and supporting individual professionals. Management needed to understand the workload and time required to carry out collaborative care planning but also enable professionals to feel confident in their roles.

A majority of the communication between health and social care professionals was digital communication through an e-platform, and they felt it was easy to get in touch and share information. Generally, they believed they had good teamwork and an ongoing collaboration within their organization and other organizations and with the older adult and informal caregiver. However, there were areas to improve.

“I feel a disadvantage with the new way of working is that the hospital has withdrawn too far. There have been times when they refused to participate, and if they do not participate, there will be a gap. If we lose that part, how will we be able to make the person safe when we do not know what has happened in the hospital?” (Care organizer, Municipality)

The health and social care professionals thought developing common routines and guidelines for the collaborative care planning process would facilitate collaboration between actors. It was important to work as one, provide information and carry out the process in the same way. They depended on each other and often based decisions during the collaborative care planning process on each other’s work. They wanted more time for reflection and discussion so they could learn from each other.

According to the professionals, how the collaborative care planning process was carried out depended on the coordinator. The coordinator mainly had an administrative role and facilitated work before and during the conference. After the collaborative care planning conference, the coordinator role was often transferred from the health clinic to the municipality. However, different professionals interpreted the role of the coordinator differently, and this affected their work.

4.3.3. Adjusting to the person

The majority of older adults participating in the collaborative care planning process were ill and/or frail, and it was difficult for them to take an active part. They depended on their informal caregivers to represent them. Among the informal caregivers, there were persons with disabilities, e.g., hearing impairment. The professionals struggled to create an enabling environment. Being flexible and adjusting to different persons and situations was a challenge. For example, no adjustments of the environment or uses of aids to facilitate communication were observed during the collaborative care planning conferences.

“We are still not good at adjusting to the person. We have to carefully select the participants for the conference and create a feeling of safety so they are free to express themselves during the conference. Collaboration and coordination are important, but it should be done in a good way for the person”. (PT, Municipality)

The health and social care professionals were encouraged to use video conference for the collaborative care planning conference so they could participate from their offices and not have to travel to the person’s home. However, not all professionals supported the use of video conference. They thought there were many issues with using video conference, and it was not suitable for older and/or frail persons. The professionals saw a value in having the collaborative care planning conference at the older adults home, a natural way of getting to know their context.

4.3.4. Balancing power differences

The health and social care professionals recognized power differences on different levels. Informants expressed concerns over the minor role they felt healthcare played in the care and services provided in the person’s home.

The professionals acknowledged it was a challenge to change the way of working, and they sometimes forgot to involve, or did not talk with the older adult or informal caregiver. The professionals felt there were different interpretations of the purpose of collaborative care planning, and they wanted the purpose to be well defined. Further, if the older adult and informal caregiver did not want the same thing, it became a challenge for the professionals.

“Sometimes it is obvious they do not want the same thing, but other times you just get a feeling … it is important to analyse and reflect over who are we there for, the worried relative or the patient. Who are we there for?” (Nurse, Municipality)

4.3.5. Creating a plan

Before the conference, the professional assessed the older adult’s needs. However, not all professionals made their assessments together with the person. During observation of collaborative care planning conferences, it became clear that health and social care professionals also used the conference to collect information. The professionals thought they could be better in assisting the older adult and informal caregiver in preparing themselves before the conference.

While a guideline was developed for how to conduct a good meeting, not all used it. How the conference was conducted and the quality achieved depended mainly on the coordinator responsible. The professionals saw it as their responsibility to guide and assist the older adult in formulating goals and breaking them down into objectives. The main goal was often formulated ahead of the conference instead of arising from discussions during the conference. Not all professionals asked for the older adult’s goals or assumed the needs they identified were the same as the older adult’s goals.

After the conference, the participating professionals documented their part in the collaborative care plan. At the municipality, they discussed the care plan at team meetings, but otherwise they did not use the care plan and thought it was not necessary for them to carry out their work and adhere to the agreements. They acknowledged that follow-ups of the collaborative care plan were not done regularly. The outcome of the collaborative care planning depended on how professionals carried out their part in the process and how they, with the older adult and informal caregiver, connected the different links.

5. Discussion

The results explained the core attributes for a successful collaborative care planning process, i.e. a joint philosophy, everyday practice and planning through partnership. The conceptual model described how the attributes linked to each other, influenced each other and worked in synergy. If one or more attributes did not function in an optimal way or was missing, it affected the collaborative care planning process and had consequences for the older adult. The results highlighted a discrepancy of the health and social care professionals’ thoughts of what was important attributes for a successful collaborative care planning process, and the collaborative care planning process they actually carried out.

The results also showed that the collaborative care plan developed during the process was a result of personal, interpersonal and organizational aspects, including a process of interprofessional collaboration, (cf. Jerôme et al., Citation2016b) and the health and social care professionals’ ability to create a partnership and integrate the older adult and informal caregiver into the team and process. According to Tondora et al. (Citation2012), the care plan often turned out to be a technical document with no usefulness to the professionals or older adult and played little, if any, role in guiding care. This is in line with this study’s findings and points out the importance of having a clear purpose for developing the care plan.

The foundation of the collaborative care planning process was identified to be a joint philosophy, i.e. a person-centred approach. However, the participants had no consensus about the definition of personcentredness or how it should be carried out. Hower et al. (Citation2019) stated that a common understanding of person-centred care in healthcare and social services is lacking in practice. This understanding often depends on the professionals’ definition and the context of healthcare and social services. Social workers ascribe different attributes to personcentredness than do nurses and medical doctors, despite agreeing on its overall principles (Gachoud et al., Citation2012). To facilitate the new way of working, management should create arenas where, with the health and social care professionals, they can reflect, discuss and agree on a definition of the person-centred approach, everyday practice and collaborative care planning. When professionals from different organizations collaborate, it is vital that they share the same definition of personcentredness and define and carry out its attributes in the same way, otherwise personcentredness will not be visible in everyday practice. According to Dellenborg et al. (Citation2019), professionals need guidance in internalizing their insights on a new way of working and integrating this as part of their work. If older adults are to benefit from a person-centred approach, it must become part of daily practice.

For personcentredness to be successfully implemented in healthcare and social services, implementation must cover all levels, i.e. individual level (personal traits, skills, attitudes, etc.), organizational level (management, resources, culture, etc.) and system level (regulations, patients’ rights, politics, etc.) (Hower et al., Citation2019). There is increasing pressure to implement person-centred approaches in Sweden through different policies in healthcare and social services. However, culture in Swedish healthcare organizations has been described as conservative and difficult to change (Alharbi et al., Citation2012). Despite legal requirements, patient participation is prevented by organizational systems and paternalism (Moore et al., Citation2016).

When collaborating between different actors, there are also various barriers to regard. Healthcare and social service have different legal frameworks, budgets, IT systems, geographical boundaries, cultures and ways of training and educating professionals (Glasby, Citation2016; Hansson et al., Citation2018). In their work, professionals and their managers tend to adopt organizational perspectives that emphasize processes rather than outcomes, i.e. successes are numbers of care plans rather than better care coordination (Redding, Citation2013). A new way of working demands organizational changes and strong leadership. According to Stanhope et al. (Citation2015), organizations must convey a clear sense of mission and goals, promote cohesion and cooperation, provide necessary resources and reflect on openness to change. Changing the culture requires an ongoing and sustained commitment (McCormack & McCance, Citation2016). The system, organization and individual professionals must recognize that being person-centred in one situation does not mean being person-centred in another situation. Space and flexibility on all levels are needed to cater to the unique person. Interprofessional collaboration is a complex and dynamic process requiring certain competences and skills of the professionals involved (Jerôme et al., Citation2016b). Professionals need to be familiar with each other’s expertise, roles and responsibilities (Légaré et al., Citation2011). The team must develop good communication, cooperation, leadership (Menefee, Citation2014) and foster mutual respect and trust among team members, including the older adult.

In the study, the older adults and informal caregivers struggled to become part of the collaborative care planning process. For the older person and informal caregiver to become true partners, professionals need to be ready to question their power (D’Amour et al., Citation2005) and provide support (Wolff et al., Citation2016). Not all professionals have the desire to practice personcentredness, and the organization and care environment do not always support practice in a way that fosters partnership (Ells et al., Citation2011). Learning to practice according a person-centred approach is challenging and time consuming (Westgård et al., Citation2019). Professionals need basic knowledge, attitudes and skills (Morgan & Yoder, Citation2012), and management should provide targeted education and training and create continual fora for discussions related to personcentredness and the collaborative care planning process to achieve and maintain the new way of working. According to Hower et al. (Citation2019), person-oriented behaviour needs to be valued, rewarded and if not achieved, then responded to by managers.

To develop a collaborative care plan considering the older adult’s goals, preferences and capabilities, participants in the collaborative care planning conference need to work through a collaborative partnership. Such partnership encourages and empowers older adults (Ekman et al., Citation2011), acknowledges their expertise about themselves and their health (Manley, Citation2016), and gives informal caregivers the possibility to share their knowledge and situation. For health and social care professionals, it facilitates understanding the situation of the older adult and informal caregiver and their relationship with health and illness. However, the study revealed that the professionals’ opinions and perspectives formed the basis of collaborative care planning, and the shift from a professional focus to person-centred approach has not yet occurred. For the collaborative care planning process to work for all participants, professionals need to acknowledge the importance of having a joint philosophy (i.e. a person-centred approach), implementing the philosophy in their everyday practice, and carry out planning through partnership.

5.1. Methodological considerations

The study has some limitations. Selection of the participants was done through purposive sampling, and there were some challenges in recruiting older adults and informal caregivers. In selecting the health and social care professionals, we aimed for different disciplines from actors working at different facilities to get a variety of views. There is a risk that those participating had higher motivation and interest in the research topic. However, participants came from four municipalities. The focus during the observations was the person-centred attributes displayed or not presented. There was a risk that the participants changed their behaviour when they were being observed. The researcher interacted with the participants ahead of the conferences. This contributed in building trust and making the researcher less threatening during the observation.

To assess the analysis of the study, four criteria for trustworthiness will be discussed: credibility, originality, resonance and usefulness (Charmaz, Citation2014). Using multiple data sources provided rich data from older adults, informal caregivers, professionals and managers. Providing links between the data, analysis and results increased the study’s credibility. Originality was achieved by providing perspectives and insights from participants in the collaborative care planning process. From the data available, it is believed that the categories portray the fullness of the experience and thereby contribute to achieving resonance. Usefulness has been achieved by offering interpretations participants can use in care planning processes and increase knowledge of the different participants’ views of the collaborative care planning process.

5.2. Conclusion

This study has contributed to bringing together the different participants’ perspectives of the collaborative care planning process. It describes the attributes contributing in making the collaborative care planning process successful for the participants involved and explains why the collaborative care planning process is not always carried out in an optimal way. Implementing a new way of working is challenging and demanding. The study confirms the complexity of collaboration between actors, professionals, older adults and informal caregivers. Collaborative care planning is more than the care plan developed. The process has to be seen in a larger context for it to be person-centred. By deciding and agreeing on a joint philosophy, professionals will have an ethic to guide them in everyday practice and through all the steps of the collaborative care planning. This ethic will assist and facilitate professionals in getting to know the older adult and informal caregiver as persons, create a partnership, engage them as active partners in the process and facilitate take decisions together. Further research is needed to understand co-creation and goal setting in collaborative care planning from an ethical perspective and what role the collaborative care plan has in healthcare and social services.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ingela Jobe

This study was carried out within a research project researching the collaborative care planning process as a person-centred practice. The first author was a PhD student within this project. Four other studies have taken place within the same project.

References

- Alharbi, T. S. J., Ekman, I., Olsson, L., Dudas, K., & Carlström, E. (2012). Organizational culture and the implementation of person centred care: Results from a change process in Swedish hospital care. Health Policy, 108(2–3), 294–19. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2012.09.003

- Anell, A., & Glenngård, A. H. (2014). The use of outcome and process indicators to incentivize integrated care for frail older people: A case study of primary care services in Sweden. International Journal of Integrated Care, 14(4), e038. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5334/ijic.1680

- Asakawa, T., Kawabata, H., Kisa, K., Terashita, T., Murakami, M., & Otaki, J. (2017). Establishing community-based integrated care for elderly patients through interprofessional teamwork: A qualitative analysis. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare, 10, 399–407. https://doi.org/10.2147%2FJMDH.S144526

- Berglund, H., Dunr, A., Blomberg, S., & Kjellgren, K. (2012). Care planning at home: A way to increase the influence of older people. International Journal of Integrated Care, 12(5), e134. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5334/ijic.817

- Bjerkan, J., Richter, M., Grimsmo, A., Helles, R., & Brender, J. (2011). Integrated care in Norway: The state of affairs years after regulation by law. International Journal of Integrated Care, 11(1), e001. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5334/ijic.530

- Burt, J., Rick, J., Blakeman, T., Protheroe, J., Roland, M., & Bower, P. (2014). Care plans and care planning in long-term conditions: A conceptual model. Primary Health Care Research & Development, 15(4), 342–354. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S1463423613000327

- Charmaz, K. 2014. Constructing grounded theory. (2nd Ed.). Los Angeles: SAGE Publications.

- Claassens, L., Widdershoven, G., Van Rhijn, S., Van Nes, F., Van Groenou, M. B., Deeg, D., & Huisman, M. (2014). Perceived control in health care: A conceptual model based on experiences of frail older adults. Journal of Aging Studies, 31, 159–170. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaging.2014.09.008

- Condelius, A., Jakobsson, U., & Karlsson, S. (2016). Exploring the implementation of individual care plans in relation to characteristics of staff. Open Journal of Nursing, 6(8), 582–590. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4236/ojn.2016.68062

- Coulter, A., Entwistle, V. A., Eccles, A., Ryan, S., Shepperd, S., & Perera, R. (2015). Personalised care planning for adults with chronic or long‐term health conditions. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (3), Art.No.: CD010523. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD010523.pub2

- D’Amour, D., Ferrada-Videla, M., San Martin Rodriguez, L., & Beaulieu, M. (2005). The conceptual basis for interprofessional collaboration: Core concepts and theoretical frameworks. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 19(sup1), 116–131. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820500082529

- Dahlgren, L., Emmelin, M., & Winkvist, A. 2007. Qualitative methodology for International public health. Epidemiology and Public Health Sciences, Department of Public Health and Clinical Medicine, Umeå University

- Dellenborg, L., Wikström, E., & Erichsen, A. A. (2019). Factors that may promote the learning of person-centred care: An ethnographic study of an implementation programme for healthcare professionals in a medical emergency ward in Sweden. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 24(2), 353–381. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-018-09869-y

- Duner, A. (2013). Care planning and decision-making in teams in Swedish elderly care: A study of interprofessional collaboration and professional boundaries. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 27(3), 246–253. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.2012.757730

- Ekman, I., Swedberg, K., Taft, C., Lindseth, A., Norberg, A., Brink, E., & Kjellgren, K. (2011). Person-centred care—Ready for prime time. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 10(4), 248–251. https://doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.ejcnurse.2011.06.008

- Ells, C., Hunt, M. R., & Chambers-Evans, J. (2011). Relational autonomy as an essential component of patient-centred care. IJFAB: International Journal of Feminist Approaches to Bioethics, 4(2), 79–101. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3138/ijfab.4.2.79

- Gachoud, D., Albert, M., Kuper, A., Stroud, L., & Reeves, S. (2012). Meanings and perceptions of patient-centeredness in social work, nursing and medicine: A comparative study. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 26(6), 484–490. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.2012.717553

- Glasby, J. (2016). Person-centred approaches: A policy perspective, B. McCormack & T. McCance Eds., Person-centred practice in nursing and health care: Theory and practice. ISBN 9781118990568. 67–76. John Wiley & Sons

- Glaser, B., & Strauss, A. (1967). Grounded theory: The discovery of grounded theory. Sociology the Journal of the British Sociological Association, 12 (1), 27–49. 0038-0385. ISBN 0-202-30260-1.

- Gonçalves‐Bradley, D. C., Lannin, N. A., Clemson, L. M., Cameron, I. D., & Shepperd, S. (2016). Discharge planning from hospital. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 1. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD000313.pub5

- Hansson, A., Svensson, A., Ahlström, B. H., Larsson, L. G., Forsman, B., & Alsén, P. (2018). Flawed communications: Health professionals’ experience of collaboration in the care of frail elderly patients. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 46(7), 680–689. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1403494817716001

- Hower, K. I., Vennedey, V., Hillen, H. A., Kuntz, L., Stock, S., Pfaff, H., & Ansmann, L. (2019). Implementation of patient-centred care: Which organisational determinants matter from decision maker’s perspective? Results from a qualitative interview study across various health and social care organisations. BMJ Open, 9(4), e027591. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027591

- Jansen, D. L., Heijmans, M., & Rijken, M. (2015). Individual care plans for chronically ill patients within primary care in the Netherlands: Dissemination and associations with patient characteristics and patient-perceived quality of care. Scandinavian Journal of Primary Health Care, 33(2), 100–106. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3109/02813432.2015.1030167

- Jerôme, V. D., Jacques, J., Van Bokhoven, M. A., Daniëls, R., Van Der Weijden, T., Emonts, W., Petronella, W. G., & Beurskens, A. (2016b). Developing interprofessional care plans in chronic care: A scoping review. BMC Family Practice, 17(1), 137. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-016-0535-7

- Jobe, I., Lindberg, B., Nordmark, S., & Engström, Å. (2018). The care‐planning conference: Exploring aspects of person‐centred interactions. Nursing Open, 5( 2),120–130. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/nop2.118

- Karam, M., Brault, I., Van Durme, T., & Macq, J. (2018). Comparing interprofessional and interorganizational collaboration in healthcare: A systematic review of the qualitative research. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 79, 70–83. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.11.002

- Kitzinger, J. (1995). Qualitative research. introducing focus groups. BMJ: British Medical Journal, 311(7000), 299–302. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.311.7000.299

- Kristensson, J., Andersson, M., & Condelius, A. (2018). The establishment of a shared care plan as it is experienced by elderly people and their next of kin: A qualitative study. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 79, 131–136. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2018.08.013

- Légaré, F., Stacey, D., Pouliot, S., Gauvin, F., Desroches, S., Kryworuchko, J., … Gagnon, M. (2011). Interprofessionalism and shared decision-making in primary care: A stepwise approach towards a new model. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 25(1), 18–25. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.2010.490502

- Manley, K. .(2016). An overview of practice development, B. McCormack & T. McCance Eds., Person-centred practice in nursing and health care: Theory and practice. ISBN 9781118990568. 133–149. John Wiley and Sons.

- McCormack, B., Borg, M., Cardiff, S., Dewing, J., Jacobs, G., Janes, N., Karlsson, B., McCance, T., Mekki, T. E., Porock, D., Van Lieshout, F., & Wilson, V. (2015). Person-centredness - the ‘state’ of the art. International Practice Development Journal, 5(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.19043/ipdj.51.trib

- McCormack, B., & Dewing, J. (2019). International community of practice for person-centred practice: Position statement on person-centredness in health and social care. International Practice Development Journal, 9(1), 1. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.19043/ipdj.91.003

- McCormack, B., & McCance, T. (2016). Person-centred practice in nursing and health care: Theory and practice. John Wiley & Sons.

- Menefee, K. S. (2014). The Menefee model for patient-focused interdisciplinary team collaboration. JONA: The Journal of Nursing Administration, 44(11), 598–605. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/NNA.0000000000000132

- Moore, L., Britten, N., Lydahl, D., Naldemirci, Ö., Elam, M., & Wolf, A. (2016). Barriers and facilitators to the implementation of person‐centred care in different healthcare contexts. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 31(4), 662–673. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.12376

- Morgan, S., & Yoder, L. H. (2012). A concept analysis of person-centred care. Journal of Holistic Nursing, 30(1), 6–15. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0898010111412189

- Newbould, J., Burt, J., Bower, P., Blakeman, T., Kennedy, A., Rogers, A., & Roland, M. (2012). Experiences of care planning in England: Interviews with patients with long term conditions. BMC Family Practice, 13(1), 71. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-13-71

- Norrbotten, R. (2019). Informationsmaterial om Min Plan. [Information material the project ”My Plan”]. Luleå, Sweden: Region Norrbotten Sweden. http://www.norrbotten.se/sv/Utveckling-och-tillvaxt/Utveckling-inom-halso-och-sjukvard/Utvecklingssatsningar/Avslutade-projekt/Min-plan/Informationsmaterial/

- Organization, W. H. (2018). Continuity and coordination of care: A practice brief to support implementation of the WHO framework on integrated people-centred health services. World Health Organization.

- Redding, D. (2013). The narrative for person-centred coordinated care. Journal of Integrated Care, 21(6), 315–325. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/JICA-06-2013-0018

- Reeves, D., Hann, M., Rick, J., Rowe, K., Small, N., Burt, J., … Richardson, G. (2014). Care plans and care planning in the management of long-term conditions in the UK: A controlled prospective cohort study. The British Journal of General Practice : The Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners, 64(626), e56–e575. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp14X681385

- Rustad, E. C., Furnes, B., Cronfalk, B. S., & Dysvik, E. (2016). Older patients’ experiences during care transition. Patient Preference and Adherence, 10, 769–779. https://doi.org/10.2147%2FPPA.S97570

- SFS (2017:612). Lag om samverkan vid utskrivning från sluten hälso- och sjukvård. [The collaboration at discharge from hospital Act]. Stockholm, Sweden: Ministry of Health and Social Affairs, the Swedish Government. https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-lagar/dokument/svensk-forfattningssamling/lag-2017612-om-samverkan-vid-utskrivning-fran_sfs-2017-612

- Shiner, A., Ford, J., & Steel, N. Care plan use among older people with functional impairment: Analysis of the English general practice patient survey. (2018). European Journal for Person Centred Healthcare, 6(4), 571–578. 2052-5656. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5750/ejpch.v6i4.1547

- Stanhope, V., Tondora, J., Davidson, L., Choy-Brown, M., & Marcus, S. C. (2015). Person-centred care planning and service engagement: A study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials, 16(1), 180. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-015-0715-0

- Timmins, N., & Ham, C. (2013). The quest for integrated health and social care: A case study in Canterbury. Kings Fund London.

- Tondora, J., Miller, R., & Davidson, L. (2012). The top ten concerns about person-centred care planning in mental health systems. International Journal of Person Centered Medicine, 2(3), 410–420. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5750/ijpcm.v2i3.132

- Van Dongen, Jerôme Jean Jacques, Lenzen, S. A., Van Bokhoven, M. A., Daniëls, R., Van Der Weijden, T., & Beurskens, A. (2016a). Interprofessional collaboration regarding patients’ care plans in primary care: A focus group study into influential factors. BMC Family Practice, 17(1), 58. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-016-0456-5

- Westgård, T., Wilhelmson, K., Dahlin-Ivanoff, S., & Ottenvall Hammar, I. (2019). Feeling respected as a person: A qualitative analysis of frail older people’s experiences on an acute geriatric ward practicing a comprehensive geriatric assessment. Geriatrics, 4(1), 16. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics4010016

- Wolff, J. L., Spillman, B. C., Freedman, V. A., & Kasper, J. D. (2016). A national profile of family and unpaid caregivers who assist older adults with health care activities. JAMA Internal Medicine, 176(3), 372–379. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.7664

- World Health Organization. (2015). WHO global strategy on people-centred and integrated health services: Interim report.