Abstract

We report on a 21-year-old male patient, suffering from bilateral acute hearing loss and vertigo. The article presents the clinical course of autoimmune inner ear disease, including diagnostic approaches and challenges, as well as therapeutic strategies and clinical follow-up. Response to corticosteroids often decreases during the course of the disease, requiring a more targeted treatment, such as the use of biological agents to block cytokines like interleukin 1 (IL-1) and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα). In our case, hearing thresholds improved considerably under immune-modulating therapy, while vestibular function remained reduced. In case of autoimmune inner ear disease, therapies targeting IL-1 and TNFα for consecutive reduction of cytokine activity represent an effective remedy for the measurable restoration of sensory function.

Introduction

Sudden sensorineural hearing loss (SSNHL) continues to represent a challenging task in respect of identifying the underlying disease or event and choosing the best therapeutic strategy.

Moreover, the negative impact of permanent hearing loss can be enormous, influencing nearly every aspect of the patient’s life [Citation1]. In the vast majority of cases, the actual reason for the clinical symptom of SSNHL remains unclear even after extensive diagnostic work-up, leading to the final diagnosis of idiopathic SSNHL (ISSNHL). However, a specific clinical course and certain diagnostic results can lead to a more comprehensive diagnosis other than ISSNHL.

The following report presents the rare case of a patient suffering from autoimmune inner ear disease (AIED), his clinical symptoms, the diagnostic work-up leading to the diagnosis, consecutive specific treatment, and long-term follow-up over 2 years.

Case report

Informed consent for the publication of anonymized data was obtained from the patient.

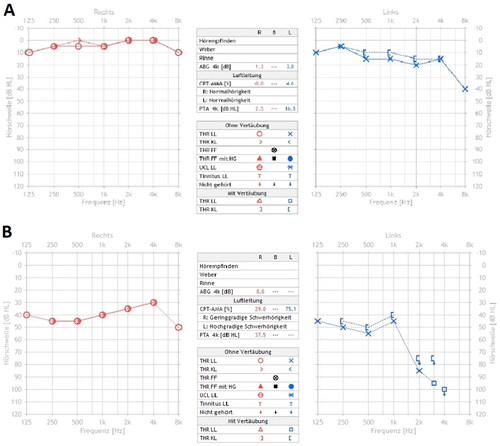

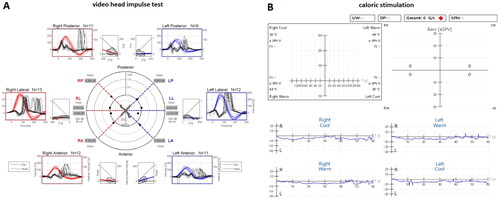

We describe the case of a 21-year-old male patient, who presented in the outpatient clinic due to acute hearing loss of the left ear and slight spinning vertigo. Ear microscopy was unremarkable. The vestibular examination showed a spontaneous right beating nystagmus and a pathologic head impulse test on the left side. Besides a decrease of 20 dB in frequencies above 1.0 kHz, pure-tone audiometry (PTA) revealed hearing threshold levels between 0–5 dB. Assuming a slight ISSNHL combined with a vestibular dysfunction of the left side, the patient received intravenous therapy with prednisolone, which improved the symptoms within a few days, showing a full remission of SSNHL in the audiogram. However, two weeks later a relapse with aggravated symptoms occurred. This time repeated systemic therapy with intravenous prednisolone for three days showed no appreciable effect, nor did a subsequent intratympanic application of triamcinolone acetonide. Ten days later the patient developed an SSNHL of the contralateral right ear. Consequently, PTA revealed a bilateral asymmetric SSNHL with progression on the previously affected left side. Furthermore, the patient suffered from bilateral tinnitus and vestibular symptoms confirmed by videonystagmography (Figure ).

Figure 1. A + B: pure tone audiogram of right (red) and left (blue) ear, air and bone conduction. A: audiogram at initial consultation: hearing thresholds within normal limits, slight decrease in mid and high frequencies on the left side compared to the right side. B: follow-up audiogram after 4 weeks: bilateral asymmetric sensorineural hearing loss.

Figure 2. A: Video head impulse test: loss of function of all six semicircular canals on both sides. B: Air caloric stimulation (warm and cold): missing response on both sides.

Imaging of the temporal bone including a computed tomography scan and magnetic resonance imaging remained unremarkable apart from a decreased fluid signal of the anterior and posterior semicircular canals (SCC) on both sides. An endolymphatic hydrops could be excluded.

The following months, repeated audiometric measurements documented strongly fluctuating hearing levels, with the left ear consistently more affected. Hearing threshold levels ranged from normal limits to a maximum decrease of 50 dB on the right side and 65 to 100 dB on the left side. Vestibular symptoms remained unchanged. The patient repeatedly received systemic and intratympanic corticosteroids, but relief from symptoms proved only temporary. Furthermore, long-term therapy with oral prednisolone (40 mg/day) up to three months did not show any lasting effect.

Blood tests for common systemic autoimmune diseases, immune deficiency and chronic infectious diseases were all negative. In the synopsis of the symptoms and the course of the disease, corticosteroid-resistant AIED was assumed to be the most accurate diagnosis.

We decided to perform plasmapheresis (four times in total), which resulted in a slight improvement in hearing levels, only to be followed by a consecutive relapse shortly after. Due to its invasiveness, effort and lack of lasting effectiveness, plasmapheresis was discontinued. Instead, we started a systemic immune therapy with the IL-1-receptor antagonist Anakinra. During the following weeks, hearing levels increased bilaterally, although still fluctuating, while the tinnitus improved only slightly, and vestibular symptoms remained unaffected. Therapy was later changed to the TNFα-antibody Adalimumab, as the application interval is longer, which was more suitable for the patient. Even though both substances were well tolerated, and follow-up confirmed more stable hearing levels (Figure ), treatment with Adalimumab was discontinued after 6 months, due to the patient’s request for a withdrawal trial. Follow-up showed ongoing fluctuations of hearing levels bilaterally, but no further aggravation. An MRI control after one year showed no changes. Regular follow-ups are still ongoing.

Figure 3. Audiometric follow-up of both ears for 24 months (Jan 2019 – Jan 2021) (x-axis), given in PTA [0.5–4 khz; dBHL] (y-axis) for each ear – red: right; blue: left. Arrows mark the initiation of each therapeutic agent.

![Figure 3. Audiometric follow-up of both ears for 24 months (Jan 2019 – Jan 2021) (x-axis), given in PTA [0.5–4 khz; dBHL] (y-axis) for each ear – red: right; blue: left. Arrows mark the initiation of each therapeutic agent.](/cms/asset/92e4eecc-3734-4b1b-9330-70c6ec0817ac/icro_a_2176309_f0003_c.jpg)

Tables and present an overview of the performed diagnostic procedures and applied therapies.

Table 1. Performed diagnostic procedures.

Table 2 Applied therapies including dose, duration, and type of administration.

Discussion

This case report displays the clinical course and challenges of AIED. The diagnosis is challenging as specific tests or parameters defining the disease do not exist, yet. Instead, only the clinical presentation and course of disease (progressive bilateral asymmetric fluctuating SNHL with or without vestibular symptoms and tinnitus) in context with the development of corticosteroid-resistance, represent the most important hints for diagnosis. It is obligatory to exclude other possible autoimmune and infectious diseases or congenital disorders. In some patients, the presence of autoantibodies has been described, but unlike other autoimmune diseases, their presence in AIED is inconsistent. It is under debate, whether the origin of AIED is caused by an autoimmune or autoinflammatory process, as AIED has features of both [Citation2].

According to the literature, 30% of patients do not show any response to corticosteroids at all. However, similarly to our patient, the majority of affected, initially respond well to corticosteroids, but develop corticosteroid-resistance over time [Citation3]. Based on the low incidence of AIED only a few studies with small cohorts and varying results on specific therapies exist. So far, the most effective treatments are plasmapheresis and biological agents blocking either IL-1 (Anakinra), TNFα (Adalimumab, Infliximab, etc.) or B-lymphocytes (Rituximab) [Citation2].

Previous studies demonstrated an increased expression of IL-1β in corticosteroid-resistant AIED patients compared to corticosteroid-responding individuals [Citation4–6]. While IL-1α regulates immunologic reactions like the activation of TNFα, IL-1β can not only be stimulated by cytokines like TNFα, but is also capable of upregulating its own expression, creating a state of ‘autoinflammation’ [Citation7]. As the IL-1 receptor antagonist Anakinra competitively inhibits the binding of IL-1β and IL-1α to the IL-1 type I receptor (IL-1R1) Vambutas et al. performed a phase I/II open-label clinical trial with Anakinra in corticosteroid-resistant AIED patients, which resulted in audiometric improvement in seven out of ten patients [Citation6].

Even though the administration of Adalimumab is more convenient compared to that of Anakinra (injection every two weeks vs. daily application), our decision to induce a therapy with Anakinra was based on positive reports [Citation2,Citation6–8] and its favorable profile concerning side effects, which are mostly limited to minor reactions, like injection site reactions, gastrointestinal symptoms like nausea and diarrhea or headache [Citation6,Citation8,Citation9]. As guidelines on the duration of therapy or adjustment of dosage are not available, we referred to the procedures and timetable of the study of Vambutas et al. [Citation6],

Follow-up and therapy monitoring consisted of regular hearing tests and clinical examinations. Unfortunately, measurement of IL-1β was not available in our clinic. As our patient experienced daily fluctuating hearing levels which is common in AIED, it was difficult to distinguish between response to therapy and coincidental spontaneous improvement. Thus regular and continuous self-reports from patients on symptoms are essential. Over the course of three months, weekly hearing tests were performed. Figure presents average hearing threshold levels over 24 months. After initiation of Anakinra therapy, PTA was more stable with constant levels between 0–30 dB on the right side and, even though the left side also improved, moderate to severe hearing loss was still present. Due to its lower application rate and comparable efficacy, the Anakinra treatment was changed to Adalimumab [Citation2,Citation10]. In addition, our patient received a daily oral dose of 600 mg n-acetylcysteine (NAC) based on a study from Pathak et al. describing reduced TNFα release induced by NAC in AIED patients [Citation11]. NAC also has been attributed with a potential positive influence on SNHL due to its antioxidative effect [Citation12]. As changes in TNFα serum levels can be of diagnostic and prognostic value [Citation13] we analyzed TNFα serum levels before and during the therapy and could observe a decrease from originally elevated serum levels (max. 19,6 pg/ml/reference range <0,5) to low elevated levels (4–5 pg/ml). In terms of symptom control and hearing level stability, Adalimumab showed similar results to Anakinra (Figure .), while vestibular symptoms and function did not improve with either. Immunosuppressants bear the risk of higher susceptibility to infections. During therapy with both substances, no infections or other adverse events like allergic reactions or gastrointestinal symptoms occurred. Side effects were exclusively limited to mild injection site reactions, which were treated with topical NSAIDs and cooling. Under long-term therapy with prednisolone, the patient reported of a gain of weight, which stabilized after treatment was discontinued.

An MRI revealed a bilaterally reduced fluid signal of the anterior and posterior SCCs, while video head impulse testing showed pathological results in all six SCCs. The pathogenesis behind these findings remains unclear. Due to symmetric and regular SCC signals in a former MRI-scan of the patient, a congenital disorder appears unlikely. To our knowledge, there are no reports on cumulative SCC abnormalities in the context of AIED, whereas reports on radiologically detected narrowing of SCC, found in patients with bilateral SNHL, do not necessarily correlate with vestibular function disorders [Citation14]. Since inflammatory processes may cause sclerotic or fibrotic changes, it appears possible that secondary changes in the inner ear will occur during the course of AIED.

In corticosteroid-resistant AIED, biological agents for targeting inflammatory cascades seem to be the most promising option for treatments. Alternative types of drug administration like the intratympanic application of biological agents could offer a more direct and possibly more effective route, as well as an elimination of systemic side effects [Citation15].

Conclusion

In patients with fluctuating bilateral asymmetric SNHL with or without vertigo and tinnitus, AIED must be taken into consideration as a diagnosis. Comprehensive diagnostic work-up and exclusion of any other possible disease associated with SNHL is necessary. In AIED biological agents like anti-IL-1 and anti-TNFα, represent an effective remedy for individual patients with corticosteroid-resistant symptoms.

Ethical approval

This retrospective review of patient data did not require ethical approval in accordance with local/national guidelines. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of the details of his medical case and any accompanying images.

AIED is a rare and hardly understood disease, which is why there is a lack of reliable controlled clinical trials. Immune modulating agents like anakinra and adalimumab are officially approved for the treatment of common rheumatologic diseases e. g. rheumatoid arthritis. However, the use in AIED can only be recommended based on previous clinical reports, all in all with a small number of patients. In our case the use of these both substances were clearly off-label.

Treatment options were discussed and reviewed by the Department of Otorhinolaryngology and the Department of Rheumatology. Generally, all performed procedures were decided after critical risk-benefit analysis and always in consensus with the patient and attending physicians.

Informed consent

Authors confirm that consent was obtained from the patients for this study.

Acknowledgements

None.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest or competing interests.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Chandrasekhar SS, Tsai Do BS, Schwartz SR, et al. Clinical practice guideline: sudden hearing loss (update). Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;161(1_suppl):S1–S45.

- Vambutas A, Pathak S. AAO: autoimmune and autoinflammatory (disease) in otology: what is new in immune-mediated hearing loss. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol. 2016;1(5):110–115.

- Broughton SS, Meyerhoff WE, Cohen SB. Immune-mediated inner ear disease: 10-year experience. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2004;34(2):544–548.

- Vambutas A, DeVoti J, Goldofsky E, et al. Alternate splicing of interleukin-1 receptor type II (IL1R2) in vitro correlates with clinical glucocorticoid responsiveness in patients with AIED. PLOS One. 2009;4(4):e5293.

- Pathak S, Goldofsky E, Vivas EX, et al. IL-1β is overexpressed and aberrantly regulated in corticosteroid nonresponders with autoimmune inner ear disease. J Immunol. 2011;186(3):1870–1879.

- Vambutas A, Lesser M, Mullooly V, et al. Early efficacy trial of anakinra in corticosteroid-resistant autoimmune inner ear disease. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(9):4115–4122.

- Dinarello CA, van der Meer JW. Treating inflammation by blocking interleukin-1 in humans. Semin Immunol. 2013;25(6):469–484.

- Sakano H, Harris JP. Emerging options in immune-mediated hearing loss. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol. 2019;4(1):102–108.

- Fleischmann RM, Tesser J, Schiff MH, et al. Safety of extended treatment with anakinra in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65(8):1006–1012.

- Matsuoka AJ, Harris JP. Autoimmune inner ear disease: a retrospective review of forty-seven patients. Audiol Neurootol. 2013;18(4):228–239.

- Pathak S, Stern C, Vambutas A. N-Acetylcysteine attenuates tumor necrosis factor alpha levels in autoimmune inner ear disease patients. Immunol Res. 2015;63(1-3):236–245.

- Angeli SI, Abi-Hachem RN, Vivero RJ, et al. L-N-Acetylcysteine treatment is associated with improved hearing outcome in sudden idiopathic sensorineural hearing loss. Acta Otolaryngol. 2012;132(4):369–376.

- Svrakic M, Pathak S, Goldofsky E, et al. Diagnostic and prognostic utility of measuring tumor necrosis factor in the peripheral circulation of patients with immune-mediated sensorineural hearing loss. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;138(11):1052–1058.

- Van Rompaey V, De Belder F, Parizel P, et al. Semicircular canal fibrosis as a biomarker for lateral semicircular canal function loss. Front Neurol. 2016;7:43.

- Breslin NK, Varadarajan VV, Sobel ES, et al. Autoimmune inner ear disease: a systematic review of management. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol. 2020;5(6):1217–1226.