Abstract

To depict a novel surgical approach for treatment of refractory pediatric Eagle Syndrome. A retrospective chart review of one pediatric patient who underwent successful treatment of Eagle Syndrome with an endoscopic-assisted transoral approach to styloidectomy. The patient was evaluated for symptomatic relief at one month postoperatively. There were no intraoperative complications. Postoperatively, our patient reported no further pain and her operative site was well healed. She elected to undergo contralateral treatment in the coming months. There remains a paucity of literature regarding pediatric Eagle Syndrome including surgical management. While transcervical and transoral approaches remain adequate options for treatment in adults, there are significant complications associated with each. We describe a case of ES successfully treated via an endoscopic-assisted transoral approach thereby improving visibility in an operating field and achieving an ideal cosmetic outcome.

1. Introduction

Eagle Syndrome (ES) is a rare condition characterized by elongation of the styloid process or calcification of the stylohyoid ligament. It was initially described by Eagle in 1937 whereas adults with styloid processes longer than 25 mm were considered abnormal, typically elucidating pain when over 30 mm [Citation1]. The syndrome can be broken down into two subtypes, with classic or styloid-carotid symptoms. The classic syndrome symptoms include stylagia (pharyngeal pain localized to the tonsillar fossa, referred pain to the ear, and neck pain), dysphagia, and globus sensation. Styloid-carotid symptoms tend to be more varied and are caused by compression of the carotid artery by the styloid fibers. ES is most commonly caused by calcification or ossification of the stylohyoid ligament. As these processes are typically age-dependent, very limited literature exists relating to the pediatric population. Currently, only seven reported pediatric cases have been described in the literature [Citation2–4]. Historically, literature has cited past surgical trauma, including a history of tonsillectomy, as the inciting event leading to ligamentous calcification, however many reports of adult and pediatric cases include no such history [Citation1,Citation3,Citation5,Citation6].

Treatment traditionally includes both medical and surgical options. Medical therapy is the first line treatment for ES and includes oral pain medications, local steroid or anesthetic injections, antidepressants, or anticonvulsants such as gabapentin and pregabalin. For those who fail conservative treatment, surgical options are considered [Citation7]. Surgical approaches to partial styloidectomy may be transoral, managed with or without tonsillectomy, or transcervical. Microscopic decompression or excision of the entire stylohyoid chain can also be considered. Despite their own differing risks and benefits, one recent retrospective study showed no significant difference in efficacy between the transoral and transcervical approaches in adult patients with ES [Citation8]. Even so, surgeon preference and patient characteristics may play a role in surgical planning. While the transcervical approach has the advantage of adequate anatomic exposure of the styloid process and its associated structures, it carries the risk of scar formation, poor cosmetic outcome, and possible injury to the marginal mandibular branch of the facial nerve. Transoral approach has the benefit of better aesthetic outcomes but carries the disadvantages of poor visualization, neurovascular injury, and rarely deep cervical infection [Citation5,Citation6,Citation9]. Some risks of intraoral resection may be abated by an endoscopic-assisted approach. We report a pediatric case of Eagle’s syndrome treated with transoral endoscopic-assisted partial styloidectomy.

2. Case description

16-year-old female with past medical history of anxiety, depression, ADHD, and recently diagnosed ES who presented due to constant dull bilateral facial pain refractory to medical management. Over the course of two years, she had been evaluated by multiple specialists including a Dentist, Chiropractor, and another Otolaryngologist. She had tried Ibuprofen, Tylenol, antidepressants, and multiple rounds of steroids without improvement in symptoms. Pain affected the post auricular region (L > R) with radiation down the shoulders and head, worse with neck movements. She additionally complained of throat pain, globus sensation, and dysphagia significantly affecting her quality of life. CT imaging from the prior year revealed elongated styloid processes bilaterally. She elected to undergo left sided surgery. The patient underwent left endoscopic transoral resection of styloid process using NIM facial nerve monitoring. At the one month postoperative follow up, her neck pain had completely resolved, and planned to follow up for the right side in the future.

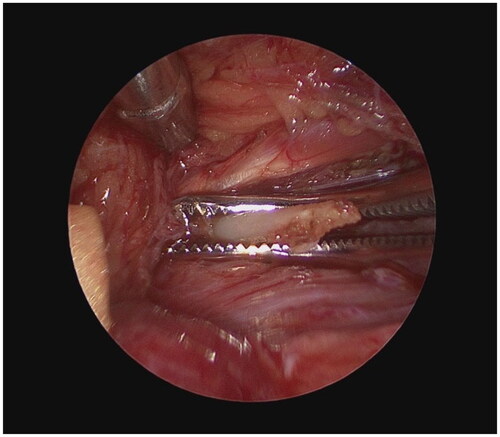

The operation was performed under general anesthesia with NIM facial nerve monitoring, without the use of neuromuscular blocking agents. The mucosa along the left tonsillar pillar was incised with a needle tip Bovie. The superior constrictor muscles were dissected with blunt dissection until the styloid process palpated, first visible with suction traction as seen in Figure Citation1. A zero-degree rigid endoscope was then used for improved visualization for the remainder of the case. Cautery followed by a freer were used to further release the styloid process of all muscular and ligamentous attachments (Figure Citation2). Under direct visualization with the endoscope, a 2 mm Kerrison was used to resect the styloid process as superior as possible toward the skull base. Palpation revealed no further prominence of the styloid. To reduce the risk of infection, the wound was copiously irrigated and closed in layers. The patient was discharged on a course of prophylactic oral antibiotics.

3. Discussion

There remains a paucity of literature regarding pediatric ES including medical and surgical management. Current diagnostic and treatment paradigms are derived from adult literature [Citation5]. Additionally, because of the low prevalence of ES in childhood, clinicians have a lower tendency to consider the diagnosis in the differential for severe orofacial pain. Therefore, pediatric patients suffering from ES may undergo a delay in diagnosis or undergo prolonged treatment with an array of pharmaceuticals with varied side effects such as in the case of our patient. Even so, despite its rarity in childhood, ES is a treatable syndrome that should remain high on the differential of recurrent neck and throat pain in the pediatric population.

In this case, we discussed a patient who was refractory to medical management and was treated successfully via an endoscopic-assisted transoral surgical approach. While transcervical and transoral approaches remain adequate options for treatment in adults, there are significant complications associated with each. These complications can include poor visualization of the styloid, injury to the carotid artery, postoperative pain and discomfort, facial nerve injury, poor cosmetic outcome secondary to neck scarring, or even intraoral scarring. One method recently introduced by Bargiel et al. describes a highly successful minimally invasive cervical styloidectomy through a small 3–4 cm neck incision in a pre-existing neck crease to reduce the risk of poor scar cosmesis in majority adult patients [Citation6]. Even so, additional studies are warranted to evaluate its utility in young patients in whom smaller anatomy may play a role in adequate visualization with this technique.

Endoscopic assistance has been described in adult ES patients with good results and mitigates much of the previously mentioned risks due to its magnification and illumination [Citation9,Citation10]. The approach demonstrated in this case may also safely and successfully treat pediatric ES patients. While most literature surrounding pediatric ES describes medical management, one report by Tanenbaum et al. demonstrates another patient successfully treated surgically with endoscopic assistance [Citation4]. With regards to our patient, she received complete remission of symptoms following partial styloidectomy.

4. Conclusion

The endoscopic-assisted transoral approach to styoidectomy in pediatric patients with ES should be considered to improve visibility in an operating field rich with important anatomical structures. This augmented technique reduces common risks associated with the transoral approach alone including that of poor visualization leading to neurovascular injury and major bleeding. Additionally, visibility limits extensive dissection which can otherwise lead to postoperative edema and intraoral scarring [Citation9]. It is important to choose the appropriate surgical method not only according to the experience of the surgeon, but according to the different pathological characteristics of the patient. While minimally invasive transcervical styloidectomy does present a promising viable alternative to extensive neck approaches, the intraoral technique may still be preferred in many young patients who wish to avoid neck incision or in those with higher risk of keloid or hypertrophic scar formation. For those patients, endoscopic assistance is a valuable tool. In our experience, surgical intervention, namely with an endoscopic-assisted transoral approach, is a safe and effective treatment for pediatric ES.

Consent

Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participant’s legal guardian.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Eagle WW. Elongated styloid processes: report of two cases. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1937;25(5):584–587. doi:10.1001/archotol.1937.00650010656008.

- Gárriz-Luis M, Irimia P, Alcalde JM, et al. Stylohyoid complex (eagle) syndrome starting in a 9-year-old boy. Neuropediatrics. 2017;48(1):53–56. doi:10.1055/s-0036-1597272.

- Kumar A, Sharawat IK, Dawman L. Eagle’s syndrome: an unusual cause of recurrent neck pain in a child. BMJ Case Rep. 2020;13(1):e232454. doi:10.1136/bcr-2019-232454.

- Tanenbaum ZG, Johng SY, Parsa KM, et al. Eagle syndrome in the pediatric population: a case report. Clin Case Rep. 2022;10(9):e6148. doi:10.1002/ccr3.6148.

- Badhey A, Jategaonkar A, Anglin Kovacs AJ, et al. Eagle syndrome: a comprehensive review. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2017;159:34–38. doi:10.1016/j.clineuro.2017.04.021.

- Bargiel J, Gontarz M, Marecik T, et al. Minimally invasive cervical styloidectomy in stylohyoid syndrome (eagle syndrome). J Clin Med. 2023;12(21):6763. doi:10.3390/jcm12216763.

- Taheri A, Firouzi-Marani S, Khoshbin M. Nonsurgical treatment of stylohyoid (eagle) syndrome: a case report. J Korean Assoc Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2014;40(5):246–249. doi:10.5125/jkaoms.2014.40.5.246.

- Wang J, Liu Y, Wang ZB, et al. Intraoral and extraoral approach for surgical treatment of eagle’s syndrome: a retrospective study. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2022;279(3):1481–1487. doi:10.1007/s00405-021-06914-2.

- Matsumoto F, Kase K, Kasai M, et al. Endoscopy-assisted transoral resection of the styloid process in eagle’s syndrome. Case report. Head Face Med. 2012;8(1):21. doi:10.1186/1746-160X-8-21.

- Al Weteid AS, Miloro M. Transoral endoscopic-assisted styloidectomy: how should eagle syndrome be managed surgically? Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;44(9):1181–1187. doi:10.1016/j.ijom.2015.03.021.