?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Platystomatid flies, one of the largest families in Diptera. Here, we determined the complete mitogenome of Euprosopia sp., which is the first for the family Platystomatidae. The 16,266 base pair (bp) mitogenome comprises of 13 protein-coding genes (PCGs), 22 transfer RNA genes (tRNAs), 2 ribosomal RNA genes, and a control region. The gene order and the orientation are similar to those of other sequenced Acalyptratae species except gene were substituted by another

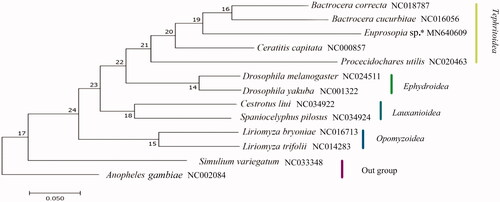

gene. All PCGs start with ATN codons, except COI and ND1, and end with TAA or incomplete stop codon TA + tRNA. The 22 tRNAs have a typical cloverleaf secondary structure. Phylogenetic analyses base on 13 Diptera species supported the monophyly of Superfamily Tephritoidea.

Platystomatid flies, one of the largest families of Acalyptratae flies, are almost distributed world-wide. It has the greatest number of species in the Old World tropics, particularly in New Guinea and tropical Africa, where many large, conspicuously marked species occur. There are around 119 known genera and nearly 1200 described species (McAlpine Citation2001). The biology of this family is rarely been studied (Ferrar Citation1987; Martínez-Sánchez et al. Citation2000). Adults of many species inhabit forests, while others live in sand dune and other vegetation types, some are attracted to fresh mammalian or other feces, some are recorded feeding at sap flows on injured trees and banana plants and sometimes at flowers, broken melons and other fruits, and the secretions of aphids.

Although three autapomorphies that prove monophyly of this family, none of them can be accepted without reservation (McAlpine Citation1989) and the monophyly of this family was not recovered in the molecular study by Han and Ro (Citation2005). The previous phylogeny researches on high-level Tephritoidea have not been in agreement, and studies about relationships among genus and subfamily of this family are limited.

Genomic DNA was extracted from tissue samples using TIANamp Micro DNA Kit (Tiangen Biotech Co., Ltd). The library was sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 2500. The bait sequence COI was amplified by standard PCR reactions, BLAST search was carried out with BioEdit 7.0.5.3. and the position of all tRNA genes was confirmed using tRNAscanSE 2.0 (Lowe and Chan Citation2016). Phylogenetic analysis was performed based on the nucleotide sequences of 13 PCGs. There are other 12 species were included in phylogenetic analysis. Using default parameters and 1000 bootstrap replicates, we constructed a phylogenetic tree based on maximum likelihood (ML) analysis by RAxML v0.6.0, which is available from the RAxML BlackBox (https://raxml-ng.vital-it.ch/#/).

Specimens of Euprosopia sp. were collected in Beibeng village of Tibet (29°14′4″N, 95°9′12″E) by Qicheng Yang, and identified by Liang Wang and Prof. Ding Yang. Specimens (CAU-HP-2019005) are deposited in the Entomological Museum of China Agricultural University (CAU). The complete mitochondrial genome of Euprosopia sp. (MK640609) was 16,226 bp in length, and consisted of 13 typical invertebrate PCGs, 22 transfer RNA genes, 2 rRNA genes (12S and 16S), and a control region, the order of majority mitochondrial genes of Euprosopia sp. were similar with related reports before (Kang et al. Citation2016; Li et al. Citation2016; Wang, Ding, et al. Citation2016; Wang, Wang, et al. Citation2016; Wang, Liu, et al. Citation2016; Li et al. Citation2017; Zhou et al. Citation2017), except gene was substituted by another

gene.

The nucleotide composition of the mitogenome was biased toward A and T, with 73.0% of A + T content (A = 40.3%, T = 32.7%, C = 16.3%, G = 10.6%). It has 16 intergenic spacer lengths from 1 to 22 bp. There are 8 overleaping regions, with overlap lengths ranging from 1 to 8 bp. Among the protein-coding genes, 6 genes took the start codon of ATG and 5 genes used ATT as start codon, while COI gene and ND1 gene got TCG and GTT, respectively. The termination codon of these protein-coding genes had three types (six genes were TAA, three genes were TAG, four genes use incomplete stop codon TA + tRNA). The longest gene in this mitochondrion was ND5 (1720 bp), and the 22 tRNA genes ranged from 62 () to 72 (

) in length. The 12S rRNA (786 bp) and 16S rRNA (1,326bp) were separated by

gene. The putative control region (1394 bp) was also located between 12S rRNA and

ML analysis () supported the monophyly at the level of superfamilies, 4 Acalyptratae families each was a monophyletic group. Tephritoidea was supported as a monophyletic clade, but the bootstrap value was not high and family Tephritidae was not recovered as monophyletic lineage.

Figure 1. The phylogenetic tree of maximum likelihood analysis based on 13 PCGs. *Indicates this study.

The complete mitochondrial genome of Euprosopia sp. provides valuable relevant information to posterior genetic and evolutionary studies of Euprosopia genus and the Platystomatidae family.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ferrar P. 1987. A guide to the breeding habits and immature stages of Diptera Cyclorrhapha. Entomonograph. 8:1–907.

- Han HY, Ro KE. 2005. Molecular phylogeny of the superfamily Tephritoidea (Insecta: Diptera): new evidence from the mitochondrial 12S, 16S, and COII genes. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 34(2):416–430.

- Kang Z, Li X, Yang D. 2016. The complete mitochondrial genome of Dixella sp. (Diptera: Dixidae). Mitochondrial DNA Part A. 27(2):1528–1529.

- Li X, Ding S, Hou P, Liu X, Zhang C, Yang D. 2017. Mitochondrial genome analysis of Ectophasia rotundiventris (Diptera: Tachinidae). Mitochondrial DNA Part B. 2(2):457–458.

- Li X, Wang Y, Su S, Yang D. 2016. The complete mitochondrial genomes of Musca domestica and Scathophaga stercoraria (Diptera: Muscoidea: Muscidae and Scathophagidae). Mitochondrial DNA Part A. 27(2):1435–1436.

- Lowe TM, Chan PP. 2016. tRNAscan-SE on-line: integrating search and context for analysis of transfer RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 44(W1):W54–W57.

- Martínez-Sánchez A, Rojo S, Marcos-García MA. 2000. Annual and spatial activity of dung flies and carrion in a Mediterranean holm-oak pasture ecosystem. Med Vet Entomol. 14:56–63.

- McAlpine DK. 2001. Review of the Australasian genera of signal flies (Diptera: Platystomatidae). Rec Aust Mus. 53(2):113–199.

- McAlpine JF. 1989. Phylogeny and classification of the Muscomorpha. In: McAlpine JF, Wood DM, editors. Manual of nearctic Diptera. Agriculture Canada Monographs, Vol. 3. Ottawa: Research Branch; p. 1397–1518.

- Wang K, Ding S, Yang D. 2016. The complete mitochondrial genome of a stonefly species, Kamimuria chungnanshana Wu, 1948 (Plecoptera: Perlidae). Mitochondrial DNA Part A. 27(5):3810–3811.

- Wang K, Wang Y, Yang D. 2016. The complete mitochondrial genome of a stonefly species, Togoperla sp. (Plecoptera: Perlidae). Mitochondrial DNA Part A. 27(3):1703–1704.

- Wang Y, Liu X, Yang D. 2016. The complete mitochondrial genome of a fishfly, Dysmicohermes ingens (Chandler) (Megaloptera: Corydalidae: Chauliodinae). Mitochondrial DNA Part A. 27(2):1092–1093.

- Zhou Q, Ding S, Li X, Zhang T, Yang D. 2017. Complete mitochondrial genome of Allognosta vagans (Diptera, Stratiomyidae). Mitochondrial DNA Part B. 2(2):461–462.