ABSTRACT

Experiencing bereavement as a child or young person (CYP) can have long-lasting effects. The societal and environmental burdens of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic exacerbated the experience of loss and grief for many CYP, who were unable to access their usual the support networks. However, it is still unclear what is currently known and not known about the experiences of CYP bereaved during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. This review used the framework of Arksey and O’Malley and included five stages: (1) identifying the research question; (2) identifying relevant studies; (3) study selection; (4) charting the data; (5) collating, summarizing, and reporting the results. The methodological quality of the included studies was also assessed using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme tool. The PRISMA framework was used for reporting the results. The electronic databases Medline, PsychINFO, CINAHL, and PubMed were searched for relevant articles. A total of three papers meeting the inclusion criteria were included in this review and two main themes identified: (1) support (which included sub-themes; social isolation and the impact on support; support from family and friends; wider support networks); (2) Emotional impact of bereavement during a pandemic. Access to support networks is crucial for CYP to understand and process their emotions relating to their bereavement experience. The pandemic meant that many usual support networks such as family and friends were inaccessible to CYP, who struggled to deal with their experience of grief during this time. Schools are a valuable support mechanism and can help CYP understand their emotions through open discussions about their bereavement. The limited empirical evidence currently available in this area of research demonstrates an important need to further understanding of the long-term impacts of dealing with pandemic-related loss in childhood

Introduction

The SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) pandemic continues to be a significant cause of global mortality, with over 21.5 million cases of COVID-19 and 150,000 deaths reported since 2020 in the United Kingdom (UK) alone (UK Government, Citation2022). For children and young people (CYP), the impact of the pandemic is significant, with a recent modeling study estimating that 10.5 million children worldwide lost a parent or caregiver to COVID-19 (Hillis et al., Citation2022), with the loss of a father being five times more likely than that of a mother (Hillis et al., Citation2021). In the United Kingdom, the National Children’s Bureau stated that at least 10,000 CYP has lost a parent or carer to COVID-19 since 2021 (Hillis et al., Citation2021), with many more suffering the death of other family members such as grandparents and siblings, or peers.

The emotional and psychological effects of bereavement on CYP is well documented and the impact of losing a parent in childhood has been associated with depression in later life, poor educational outcomes, and risk of suicide (Birgisdóttir et al., Citation2019). CYP facing parental bereavement is also at increased risk of suicide long term (Guldin et al., Citation2015), as well as lasting psychological damage, which has been shown to be minimized with targeted interventions to support CYP and their caregivers (Bergman et al., Citation2017).

Bereavement and social isolation

Whilst experiencing a bereavement in childhood is undoubtedly traumatic, the pandemic also had additional adverse impacts on the bereavement experience: national lockdowns, social isolation and distancing measures, and restrictions on visiting in health and social care settings meant CYP were unable to see loved ones prior to, or at the time of their death. Funeral attendance was severely limited, if not impossible, meaning CYP were also unable to embark on traditional practices of honoring their loved ones' passing. Singer et al. (Citation2020) describe the unusual situation of pre-loss grief manifested in the physical separation from a loved one and lack of social support prior to death, which further negatively impacts the bereavement experience. Substantial changes to the structure of normal daily routines attributable to the pandemic also profoundly affects CYP’s ability to cope with their environment. Asgari et al. (Citation2022) used the phrase “crisis in crisis” to refer to the complexity of dealing with the loss of a loved one and the associated trauma of dealing with this loss within pandemic restrictions. Parental accounts of children who have been bereaved during the pandemic discuss the important role that social support networks such as family, peer groups and schools, play in helping CYP understands and process their experiences. Separation from loved ones before their death, social isolation, and the disruption of daily routines were central themes in the study by Harrop et al. (Citation2022), who explored parent and guardian’s perspectives of the experiences and support needs of bereaved CYP during the pandemic. Limited access to support networks (such as schools) or bereavement charities has also been found to contribute toward a lack of social support (Goss et al., Citation2022).

Social isolation during the bereavement experience also profoundly impacts CYP mental health and the literature internationally has demonstrated an increase in depression and anxiety symptoms of CYP during the pandemic. For example, Cost et al. (Citation2021) found that the stress of social isolation was associated with worsening mental health and this was more prevalent in adolescents without psychiatric diagnoses pre-pandemic. Xie et al. (Citation2020) also found that in a sample of 1784 adolescents who completed a survey about their experiences of COVID-19, including homeschooling and depression and anxiety related to the pandemic, 22.6% participants reported experiencing depressive symptoms, whilst 18.9% reported anxieties. Temple et al. (Citation2022) found that the behavioral and environmental changes attributable to the pandemic (such as social isolation) were associated with increased depression, anxiety, and substance use in a sample of 1,188 adolescents in the USA, and this was significantly worse among those who limited their social interactions due to COVID-19. Interestingly, Hu and Qian (Citation2021) found that adolescent mental health was impacted more negatively during the pandemic in those who experienced better mental health pre-pandemic.

In their rapid review of the impact of social isolation and loneliness in CYP during the pandemic, Loades et al. (Citation2020) found that social isolation and loneliness increased the risk of depression. Taken together, parental loss during the pandemic has made the bereavement experience more traumatic for CYP and their families, increasing the likelihood of complex grief (Gesi et al., Citation2020). According to Chalmers (Citation2020):

The ripple effect of the pandemic is huge and those supporting bereaved families are anticipating that their services will be needed not just now, but far into the future as the nation copes with the aftermath.

Bereavement and mental health

The impact of childhood bereavement during the pandemic on mental health has been a focal point in the literature. In their review of the literature on CYP reactions to the death of a parent or caregiver during COVID-19, Laing et al. (Citation2022) identified an increased risk of anxiety, depressive symptoms, and risky behaviors such as substance abuse, suggesting CYP are ill-equipped to deal with loss and grief in such extreme circumstances. Other research has found that the long-term impact of losing a parent in childhood has both negative (emotional and physical) and positive (personal growth) connotations. In one study, Chater et al. (Citation2022) highlighted the importance of open discussions of the experiences of grief to help CYP better deal with their loss. Consistently, Gray et al. (Citation2022) also refer to “traumatic growth” where the death of a parent/caregiver can initiate positive changes in CYP later life. However, the authors also refer to the unusual circumstances attributable to the pandemic which can be manifested in complex grief responses rather than traumatic growth.

Despite the devastating impact of bereavement during the pandemic on CYP, research on understanding the perspectives and experiences of CYP is limited. Indeed, in their review of the literature on the experiences of bereavement of all age groups during the COVID-19 pandemic, Stroebe and Schut (Citation2021) reported on a lack of empirical evidence in this area of research. The majority of evidence to date has focused on the parent/guardian accounts of how they perceive CYP experiences of bereavement and, whilst these accounts are undeniably valuable, CYP can have very different lived experiences of bereavement and trauma and process their emotions in a very different way to adults (Alvis et al., Citation2022; Kaplow et al., Citation2018). In addition, research also shows the long-term psychological benefits of engaging with children who experience trauma to understand their own perspectives (Dalton et al., Citation2019). Therefore, to effectively understand their experiences, it is crucial to explore the experiences of CYP of bereavement during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Aim

The purpose of this scoping review is to explore and synthesize the literature on the impact of bereavement during a pandemic on children and young people.

Methods

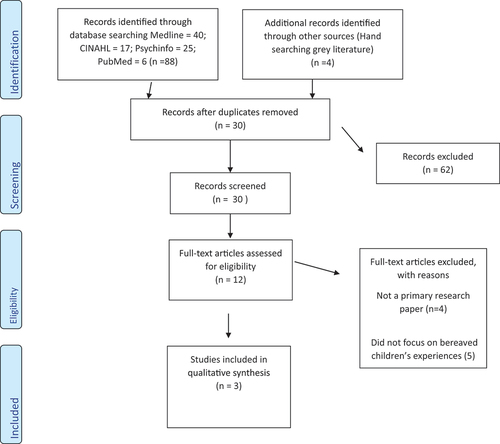

The scoping review was conducted according to the Arksey and O’Malley’s (Citation2005) framework and included five stages: (1) identifying the research question; (2) identifying relevant studies; (3) Study selection; (4) charting the data; (5) collating, summarizing, and reporting the results. This approach is particularly useful when the information available about a topic is newly emerging, has not already undergone a comprehensive review, or is from a diverse range of sources (Sucharew & Macaluso, Citation2019) and is therefore an appropriate approach for this review. The PRISMA framework was used for reporting the results ().

Identifying the research question

The research question was identified using the PEO framework (), which is considered an appropriate framework for a qualitative research question (Doody & Bailey, Citation2016).

Table 1. PEO framework to identify the research question.

The specific research question was “What is the impact of bereavement during a pandemic on children and young people?.”

Identifying relevant studies

Search strategy

The electronic databases Medline, PsychINFO, CINAHL, and PubMed were searched for relevant articles, which were published between March 2020 and March 2023 to capture the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. These medical, nursing, and health-care databases were included due to their relevance to the search strategy (Aveyard, Citation2023). Search terms reporting the views and experiences of children and young people’s experiences of bereavement, grief, and loss, were used along with those relating to the COVID-19 pandemic (see , for an example of search strategy). The gray literature, including abstracts, audits, theses, government reports, and policy documents, as well as Google Scholar, were also searched for appropriate material.

Table 2. Search strategy.

The following search terms were used:

To ensure relevant papers were included in the review, inclusion, and exclusion criteria were formulated ().

Table 3. Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Study selection

The process for study selection is outlined in (: PRISMA diagram). The titles and abstracts of each result were screened against the inclusion and exclusion criteria and duplicates removed. The titles and abstracts of the remaining papers were independently assessed by two of the authors (Author one and Author two) and then the full texts of the remaining papers (n = 12) were independently assessed for inclusion in the final review. Any disagreements between the two reviewers were resolved by discussion with the wider review team. The reference lists of the included studies were also screened for relevant papers. The remaining papers (n = 3) were included in the review.

Charting the data

Although critical appraisal is not a stage of the Arksey and O’Malley’s framework, the methodological quality of the included studies in this review were assessed using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP, Citation2018) tool to identify the strengths and limitations of the evidence.

Any information relating to the children’s experiences of bereavement during a pandemic was extracted using thematic synthesis to develop descriptive themes. This process involved the authors grouping the data into themes that were relevant to the research question in several stages; firstly, the review authors identified the key aims, objectives, methods, setting, sample, findings, and conclusions from each of the included studies, and identified the similarities and differences between them. This process led to the development of the key themes that were emerging from the findings, which was jointly discussed between the authors through an iterative process until the themes were agreed upon.

Collating, summarising and reporting the results

Setting and participant sample

All three papers were published in 2022 with two of the studies being conducted in Iran (Abdekhodaie, Citation2022; Asgari et al., Citation2022) and one in the United Kingdom (Harrop et al., Citation2022). Of the three studies, two undertook research directly with young people between the ages of 13–18 years old and directly explored the experiences of those bereaved by COVID-19; the study by Asgari et al. (Citation2022) was the only one in which all participants were considered children or young people (n = 15). Abdekhodaie (Citation2022) interviewed a total of 22 participants with three being between the ages of 13–18 years old.

One study sought the parental perspectives (n = 102) on the grief and support needs of children and young people bereaved during the COVID-19 pandemic and explored bereavement due to COVID-19, and other causes of death during the pandemic (Harrop et al., Citation2022).

Methodology

In the studies by Abdekhodaie (Citation2022) and Asgari et al. (Citation2022), data were collected through individual qualitative semi-structured interviews, but there were differences in the length of time between the participants experiencing bereavement and how the participants were recruited. Abdekhodaie (Citation2022) recruited their sample through the author’s connections with a local hospital, which was providing psychological support to families dealing with grief during the pandemic. Participants in this study were interviewed after a minimum of 6 months following the death of a family member. Asgari et al. (Citation2022) used a purposive and snowballing sampling technique to recruit participants from schools and other organizations that provided support to students who have been orphaned. In this study, participants were interviewed between 1 and 5 months following their loss. In the study by Harrop et al. (Citation2022), data were collected through analysis of qualitative free-text data from an online survey, which was administered to participants 7 months after their bereavement and investigated experiences of grief and support needs. Participants in this study were recruited through social media and charity organizations and the inclusion criteria necessitated that the participants reported on the experiences of a CYP (<25 years of age) who lived with them.

All the studies used appropriate qualitative analysis approaches and provided a description of how the analysis was conducted. The credibility of the findings was enhanced by more than one researcher being involved in the data analysis in all three of the studies. Ethical issues were addressed in each of the papers.

Themes

Two main themes were identified from this review (1) support (which included sub-themes; social isolation and the impact of support; support from family and friends; wider support networks); (2) Emotional impact of bereavement during a pandemic.

Theme one: support

Support was a central theme in all the papers included in this review and was evidenced in terms of both a lack of, and the importance of providing support, for CYP bereaved during the pandemic.

Social isolation and the impact on support

Pandemic associated measures such as social isolation, quarantine, and local and national lockdowns created unfamiliar environments for dealing with grief and loss. The inability for physical contact with loved ones prior to, or at the time of death, meant there was a lack of community support that would normally be present during such difficult times. Abdekhodaie (Citation2022) reported on the difficulties of dealing with the loss of a parent during a period of isolation, and the loneliness experienced by those who were unable to be supported by family and friends. There was ambivalence between feeling the need to withdraw from their normal everyday life, using avoidance techniques to limit their exposure to situations which may increase their negative experiences, and feeling the desire to be supported by social networks to help them deal with their traumatic experiences. Asgari et al. (Citation2022) described the social isolation enforced by the lack of funeral proceedings that would normally facilitate support from family and friends and help CYP through the grieving process.

Support from family and friends

The importance of family support was emphasized throughout the studies included in this review for not only helping CYP come to terms with their unexpected loss, but also for providing mechanisms to enable them to process and understand the impact of their bereavement. Harrop et al. (Citation2022) identified the trauma of unexpectedly experiencing a bereavement and the need for specialist support from specific services to support CYP through this process. Being unable to perform normal grieving processes (such as saying “goodbye” to loved ones) due to COVID-19 furthered the need for support from individuals outside their close family network. Asgari et al. (Citation2022) described how fear of contracting the virus limited the support and empathy offered by family members. Such stigmatizing behaviors made the bereavement experience more complex, and the lack of support from social networks also prevented usual bereavement practices such as attending a funeral, where support would usually be present in the form of family and friends. This was particularly important in this study, where funeral rituals were rooted in religious practices. The authors in this study used the term “crisis in crisis” to refer to the impact of experiencing bereavement whilst experiencing the loss inflicted by the pandemic

The study by Harrop et al. (Citation2022) further outlined the importance of maintaining and reinforcing family support in dealing with grief, and the strategies used to maintain this level of support such as open conversations and reflecting on the positive memories. In this study, parental perspectives of bereavement experiences described the importance of providing specialist (e.g. counseling) and generalist support, such as informal support from educational institutions. In particular, teachers trained in managing bereavement were identified as being particularly important for helping children and young people deal with their grief.

Wider support networks

Experiencing bereavement during the COVID-19 pandemic meant that CYP were often dealing with their grief without their usual wider support systems. Being unable to physically interact with friends had a noticeable negative impact on CYP and Harrop et al. (Citation2022) demonstrated the need for CYP seeking external support from people outside their immediate family. Building therapeutic relationships with health-care professionals, through receiving treatment from counseling and psychological services, helped them deal with their emotions. Teachers also offered informal support through being able to listen to their students’ experiences. Abdekhodaie (Citation2022) noted the external support provided by local communities and the “virtual funerals” and community activities (such as laying flowers in the local community) in helping CYP deal with their loss. The lack of normal funeral ceremonies was also highlighted in the study by Asgari et al. (Citation2022) who found that this type of social isolation intensified an already traumatic experience.

Theme two: emotional impact of bereavement during a pandemic

All studies acknowledged the emotional and psychological impacts of dealing with bereavement during a pandemic and the difficulties in accessing support which intensified the negative emotions associated with grief and loss. In particular, Harrop et al. (Citation2022) identified that children process and understand their emotions relating to bereavement differently depending on their developmental stage, and this was especially prevalent in CYP with preexisting clinical vulnerabilities who struggled with lockdown restrictions, social isolation, and being unable to visit loved ones prior to their death. Harrop et al. (Citation2022) reported on the impact that preexisting mental health problems had on the increased the likelihood of CYP suffering from anxiety and depression when attempting to deal with their experiences. The suddenness of the bereavement contributed to the loss being experienced as a traumatic event (Harrop et al., Citation2022), and without prior experience of coping with bereavement, this trauma was magnified in the study by Asgari et al. (Citation2022).

Difficulties managing and understanding emotions were manifested in feelings of anger in a study by Abdekhodaie (Citation2022), which was strongly associated with feelings of guilt. This anger was directed toward the deceased (for “letting” the virus take their life) and toward themselves, for feeling a sense of relief that they did not contract the virus. Asgari et al. (Citation2022) also reported on CYP struggling with managing feelings of guilt, loneliness, and isolation, particularly in situations where the pandemic restrictions prevented them being with their parents prior to their death, and how CYP felt their life was meaningless after the death of a parent(s). In this study, maladaptive behaviors such as drug and alcohol misuse were identified as a coping strategy.

Discussion

This scoping review aimed to explore and synthesize the literature on the impact of bereavement on CYP during a pandemic. Only three papers meeting the inclusion criteria were included in this review (Abdekhodaie, Citation2022; Asgari et al., Citation2022; Harrop et al., Citation2022), which reflects a lack of empirical research in this area. The synthesis revealed the main themes of “support” and “emotional impact of bereavement during a pandemic” which were important aspects of the experiences of CYP facing bereavement. Support came in different forms and was both formal and informal. Support from family and friends, wider support networks and professional services were identified as being important for helping CYP through their traumatic loss, whilst also experiencing pandemic related loss from other aspects of their lives such as daily routines, interactions with peers and the ability to engage in normal activities. This is consistent with the findings of Andriessen et al. (Citation2019) who explored help-seeking behaviors in bereaved adolescents and identified that a wide variety of support networks including formal (such as professional services) and informal (such as family, friends, and school networks) are essential for helping people navigate through their experiences. Informal support from schools was identified as an important aspect in supporting CYP to deal with their grief in the study by Harrop et al. (Citation2022). A key recommendation in this study was that specialist school-based collaborative initiatives would be beneficial in providing targeted support as well as being able to direct families to where they could access such support. Ensuring schools are equipped with the necessary skills to provide support to bereaved CYP was discussed by Albuquerque and Santos (Citation2021) who highlight that the need for school-based support may be increased during a pandemic when parental support can be limited due to increased stressors and pressures.

The ability to engage in open conversations was an important element of enabling CYP to navigate through their emotions of grief and loss, and suffered due to the pandemic restrictions as CYP were unable to access some of their support networks. This is something that has been discussed in the study by Rapa et al. (Citation2020), who state the importance of a truthful discourse between CYP and parents/guardians who may feel a responsibility to shield their children from negative emotions. In their detailed report of the impact of COVID-19 on CYP, Treglia et al. (Citation2021) advocates a strategic approach to identifying those children who have suffered such loss and emphasizes the importance of creating a coordinated approach to supporting CYP, through educational and community organizations to provide financial, emotional, and psychological provision.

The suddenness of the pandemic meant many CYP struggled to manage their emotions, often being manifested in maladaptive strategies for coping such as anger, guilt, and risky behaviors. Other research has identified the impact that bereavement in childhood has on experiences in adulthood; in a systematic review and meta-analysis exploring the relationship between parental bereavement and future depression, Simbi et al. (Citation2020) found that losing a parent as CYP was associated with an increased risk of depression in later life. A lack of support, most commonly due to social isolation and quarantine measures that prevented the usual practices and customs normally associated with grief and loss, intensified negative emotions and the ability to cope. These findings are consistent with previous research exploring CYP reactions to losing a parent or caregiver (Laing et al., Citation2022).

Limitations

One limitation of this review is the small number of papers meeting the inclusion criteria. Only two of the three papers directly explored the experiences of bereavement from the perspective of a child or adolescent and one paper explored the parental perspectives of their bereaved children. The participant sample varied across the studies; one paper reported a sample consisting of entirely CYP, whilst in another only three participants were considered CYP. There were also differences in the studies between the length of time that the participants experienced bereavement and the time when they were involved in the research studies, which could have contributed toward differences in their accounts of their experiences (particularly if their bereavement experience was a long time prior to their research participation, for example). Despite these limitations, the papers included in this review identified similar themes and experiences and the lack of studies meeting the inclusion criteria demonstrates an important need for further research in this area.

Conclusion

The pandemic has placed additional challenges on CYP encountering bereavement. Social isolation and distancing measures have been associated with worsening mental health, although the long-term impacts of this are yet to be understood. Access to support networks welcoming open discussions are central to enabling CYP to understand their emotions and experiences. Schools can play a vital role in providing such support. Limited empirical evidence in this area of research demonstrates an important need to further understanding of the long-term impacts of dealing with pandemic-related loss.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the following people who contributed to the study: Suzannah Phillips and Eleanor Turner from Winston’s Wish, and Professor Barry Percy-Smith, Professor Padam Simkhada and Dr Elisabeth Gulliksen from the University of Huddersfield.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abdekhodaie, Z. (2022). The lived experience of bereaved Iranian families with COVID-19 grief. Death Studies, 47(4), 381–391. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2022.2068698. Epub 2022 Apr 27. PMID: 35475416.

- Albuquerque, S., & Santos, A. R. (2021). “In the same storm, but not on the same boat”: Children grief during the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.638866

- Alvis, L., Zhang, N., Sandler, I. N., & Kaplow, J. B. (2022, January 28). Developmental manifestations of grief in children and adolescents: Caregivers as key grief facilitators. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 16(2), 447–457. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-021-00435-0. PMID: 35106114; PMCID: PMC8794619.

- Andriessen, K., Lobb, E., Mowll, J., Dudley, M., Draper, B., & Mitchell, P. B. (2019). Help-seeking experiences of bereaved adolescents: A qualitative study. Death Studies, 43(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2018.1426657. Epub 2018 Mar 14. PMID: 29393826.

- Arksey, H., & O'Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology: Theory & Practice, 8(1), 19–32.

- Asgari, Z., Naghavi, A., & Abedi, M. R. (2022). Beyond a traumatic loss: The experiences of mourning alone after parental death during COVID-19 pandemic. Death Studies, 46(1), 78–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2021.1931984. Epub 2021 May 31. PMID: 34057886.

- Aveyard, H. (2023). Doing a literature review in health and social care: A practical guide. McGraw-Hill Education.

- Bergman, A. S., Axberg, U., & Hanson, E. (2017, August 10). When a parent dies - a systematic review of the effects of support programs for parentally bereaved children and their caregivers. BMC Palliative Care, 16(1), 39. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-017-0223-y. PMID: 28797262; PMCID: PMC5553589.

- Birgisdóttir, D., Bylund Grenklo, T., Nyberg, T., Kreicbergs, U., Steineck, G., & Fürst, C. J. (2019). Losing a parent to cancer as a teenager: Family cohesion in childhood, teenage, and young adulthood as perceived by bereaved and non-bereaved youths. Psycho-Oncology, 28, 1845–1853. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5163

- Chalmers, A. (2020). The impact of the Covid-19 Pandemic on bereaved people. Child Bereavement UK. Retrieved December 14, 2023, from https://www.childbereavementuk.org/blog/the-impact-of-covid-19-on-bereaved-people

- Chater, A. M., Howlett, N., Shorter, G. W., Zakrzewski-Fruer, J. K., & Williams, J. (2022, February 13). Reflections on experiencing parental bereavement as a young person: A retrospective qualitative study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(4), 2083. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042083. PMID: 35206275; PMCID: PMC8872611.

- Cost, K. T., Crosbie, J., Anagnostou, E., Birken, C. S., Charach, A., Monga, S., Kelley, E., Nicolson, R., Maguire, J. L., Burton, C. L., Schachar, R. J., Arnold, P. D., & Korczak, D. J. (2021). Mostly worse, occasionally better: Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of Canadian children and adolescents. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 31(4), 671–684. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-021-01744-3

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. (2018). CASP Qualitative checklist [online]. Retrieved February 26, 2023 from https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/

- Dalton, L., Rapa, E., Ziebland, S., Rochat, T., Kelly, B., Hanington, L., Bland, R., Yousafzai, A., Stein, A., Betancourt, T., Bluebond-Langner, M., D’Souza, C., Fazel, M., Fredman-Stein, K., Harrop, E., Hochhauser, D., Kolucki, B., Lowney, A. C., Netsi, E., & Richter, L. (2019). Communication with children and adolescents about the diagnosis of a life-threatening condition in their parent. The Lancet, 393(10176), 1164–1176. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)33202-1

- Doody, O., & Bailey, M. (2016). Setting a research question, aim and objective. Nurse Researcher, 23(4), 19–23. https://doi.org/10.7748/nr.23.4.19.s5

- Gesi, C., Carmassi, C., Cerveri, G., Carpita, B., Cremone, I. M., & Dell'Osso, L. (2020). Complicated grief: What to expect after the Coronovirus pandemic. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 489.

- Goss, S., Longo, M., Seddon, K., Torrens-Burton, A., Sutton, E., Farnell, D., Penny, A., Nelson, A., Byrne, A., Selman, L., & Harrop, E. (2022). 15 Parents’ accounts of the grief experiences and support needs of children and young people bereaved during the COVID-19 pandemic: Results from a UK-wide online survey. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care, 21, 177. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-022-01066-4

- Gray, T. F., Zanville, N., Cohen, B., Cooley, M. E., Starkweather, A., & Linder, L. A. (2022). Finding new ground-fostering post-traumatic growth in children and adolescents after parental death from COVID-19. Journal of Adolescent Health, 70(1), 10–11.

- Guldin, M.-B., Li, J., Pedersen, H. S., Obel, C., Agerbo, E., Gissler, M., Cnattinglus, S., Olsen, J., & Vestergaard, M. (2015). Incidence of suicide among persons who had a parent who died during their childhood: A populations-based cohort study. JAMA Psychiatry, 72(12), 1227. Advanced on-line publication. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.2094

- Harrop, E., Goss, S., Longo, M., Seddon, K., Torrens-Burton, A., Sutton, E., Farnell, D. J., Penny, A., Nelson, A., Byrne, A., & Selman, L. E. (2022). Parental perspectives on the grief and support needs of children and young people bereaved during the COVID-19 pandemic: Qualitative findings from a national survey. BMC Palliative Care, 21(1), 177. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-022-01066-4

- Hillis, S., N’konzi, J. N., Msemburi, W., Cluver, L., Villaveces, A., Flaxman, S., & Unwin, H. J. T. (2022, November 1). Orphanhood and caregiver loss among children based on new global excess COVID-19 death estimates. JAMA Pediatrics, 176(11), 1145–1148. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2022.3157. Erratum in: JAMA Pediatr. 2022 Oct 3. PMID: 36066897; PMCID: PMC9449868.

- Hillis, S. D., Unwin, H. J. T., Yu, C., Cluver, L., Sherr, L., Goldman, P. S., Ratmann, O., Donnelly, C. A., Bhatt, S., Villaveces, A., Butchart, A., Bachmann, G., Rawlings, L., Green, P., Nelson, C. A., & Flaxman, S. (2021). Global minimum estimates of children affected by COVID-19- associated orphanhood and deaths of caregivers: A modelling study. Lancet, 398(10298), 391–402. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01253-8

- Hu, Y., & Qian, Y. (2021, July). COVID-19 and adolescent mental health in the United Kingdom. The Journal of Adolescent Health: Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 69(1), 26–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.04.005. PMID: 34172140.

- Kaplow, J. B., Layne, C., Oosterhoff, B., Goldenthal, H., Howell, K., Wamser-Nanney, R., Burnside, A., Calhoun, K., Marbury, D., Johnson‐Hughes, L., Kriesel, M., Staine, M. B., Mankin, M., Porter‐Howard, L., & Pynoos, R. (2018). Validation of the persistent complex bereavement disorder (PCBD) checklist: A developmentally informed assessment tool for bereaved youth. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 31(2), 244–254. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22277

- Liang, N., Becker, T. D., & Rice, T. (2022). Preparing for the COVID-19 paediatric mental health crisis: A focus on youth reactions to caretaker death. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 27(1), 228–237.

- Loades, M. E., Chatburn, E., Higson-Sweeney, N., Reynolds, S., Shafran, R., Bridgen, A., Linney, C., McManus, M. N., Borwick, C., & Crawley, E. (2020). Rapid systematic review: The impact of social isolation and loneliness on the mental health of children and adolscents in the context of COVID-19. Journal of Am Acad of Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 59(11), 1218–1239.

- Rapa, E., Dalton, L., & Stein, A. (2020). Talking to children about illness and death of a loved one during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, 4(8), 560–562.

- Simbi, C. M. C., Zhang, Y., & Wang, Z. (2020, January 1). Early parental loss in childhood and depression in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of case-controlled studies. Journal of Affective Disorders, 260, 272–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.07.087. Epub 2019 Jul 30. PMID: 31521863.

- Singer, J., Spiegel, J. A., & Papa, A. (2020). Pre-loss grief in family members of COVID-19 patients: Recommendations for clinicians and researchers. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, & Policy, 12(S1), S90–S93. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000876

- Stroebe, M., & Schut, H. (2021). Bereavement in times of COVID-19: A review and theoretical framework. Journal of Death and Dying, 82(3), 500–522.

- Sucharew, H., & Macaluso, M. (2019). Methods for research evidence synthesis: The scoping review approach. Journal of Hospital Medicine, 14(7), 416–418.

- Temple, J. R., Baumler, E., Wood, L., Guillot-Wright, S., Torres, E., & Thiel, M. (2022, September). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on adolescent mental health and substance use. The Journal of Adolescent Health: Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 71(3), 277–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2022.05.025. Epub 2022 Jul 13. PMID: 35988951; PMCID: PMC9276852.

- Treglia, D., Cutuli, J. J., Arasteh, K. J., Bridgeland, J. M., Edson, G., Phillips, S., & Balakrishna, A. (2021). Hidden pain: Children who lost a parent or caregiver to COVID-19 and what the nation can do to help them. COVID Collaborative.

- UK Government. (2022). Coronavirus (COVID-19) latest insights the latest data and trends about the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic from the Office for National Statistics and other sources. Retrieved January 25, 2023, from https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/conditionsanddiseases/articles/coronaviruscovid19/latestinsights

- Xie, X., Xue, Q., Zhou, Y., Zhu, K., Liu, Q., Zhang, J., & Song, R. (2020). Mental health status among children in home confinement during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak in Hubei Province, China. JAMA Pediatrics, 174(9), 898–900. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1619