ABSTRACT

OBJECTIVE: In the addiction treatment, treatment drop-out rates are very high. Drop-out is a crucial problem in the addiction treatment; therefore, understanding the reasons underlying this problem will help clinicians in developing new treatment strategies for treatment maintainance. In this present study, we aimed to examine the reasons for drop-out behaviour in the outpatients who presented to an addiction counseling centre in Turkey.

METHODS: This study was conducted in 554 outpatients with alcohol and/ or substance use disorder who presented to the Turkish Green Crescent Counseling Center (YEDAM) between January 2016 and July 2017. The patients were evaluated retrospectively. The sociodemographic characteristics, substance use-related and psychological characteristics were extracted by using the Addiction Profile Index (BAPI) and Addiction Profile Clinical Form (BAPI-K) included in the YEDAMSOFT software system. The patients who came to the second, fifth, and tenth sessions and the patients who dropped-out of the treatment were analyzed in order to determine the sociodemographic, substance use-related, and psychological characteristics that might caused patients to drop-out from the treatment.

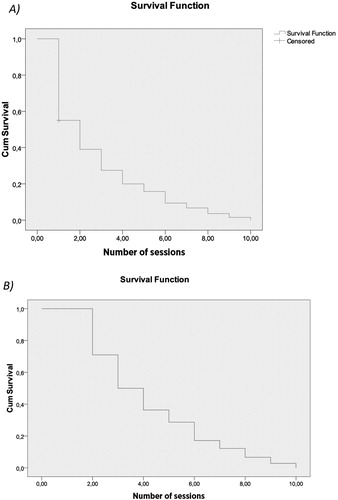

RESULTS: The drop-out rates was found higher in male patients compared to the females. Among the factors that caused drop-out behaviour were low education status, negative relationship with father, adverse effects of the substance use, severe desire for the substance use, low motivation level, being under probation, and higher numbers of psychiatric treatments in the past. We found that the factors predicted the drop-out may vary depending on the treatment session when drop-out from the treatment was actualized. The factors that predicted drop-out in the second sessions were severe desire for the substance use, being under probation order, history of psychiatric treaments in the past, and higher excitement seeking behaviour. The factors that predicted the drop-out after the fifth session were educational and marital statuses, adverse effects of the substance use, being under probation, and history of psychiatric treatments in the past. Age, educational status, and being under the probation were found as predictive factors for drop-out behaviour in the tenth session. The duration of the treatments were evaluated by Kaplan-Meier Survival Analysis. It was observed that the patients dropped-out after the 2.78th session from the first to the tenth session (CI = 2.58–2.98). It was found that the patients dropped-out after the 4.24th session from the second to the tenth session (CI = 3.98–4.51). In Cox Regression Analysis; psychiatric treatment history in the past and excitement seeking behaviour were the predictive factors for treatment drop-out with 95% confidence interval (p < 0.05).

CONCLUSIONS: It was found that the factors that caused drop out from the treatment varied on session duration as it was hypothesized. Evaluating the factors that causes drop-out from the treatment will support clinicians to improve the addiction treatment services and develop more specific, patient-tailored treatment strategies.

Introduction

One of the most important problem in addiction treatment is higher treatment drop-out rates [Citation1]. 10–30% of the patients with alcohol-substance use disorder drop-out from the treatment [Citation2]. Since these rates can vary depending on treatment forms and stages; in detox stage it is ranging from 21.5% to 43% [Citation3], in outpatient treatment programmes it might rise to 23–50% [Citation4], and in inpatient units it might be 17–57% [Citation5].

In addiction treatment, there are many risk factors that cause individuals to drop-out from treatment. The most important factors that cause drop-outs are relapses, psychiatric disorders such as antisocial personality disorder and depression [Citation6], low cognitive capacity, and low motivation. However, factors like low socioeconomic status, having long history of substance use/dependence, a history of crime, and low educational status negatively affect the continuity of treatment in substance dependence [Citation7].

In some studies, the drop-out reasons were linked to the lack of knowledge of patients about the benefits of the treatment and adaptation problems independent from the patients characteristics [Citation8]. Addiction is a brain disease that needs to be addressed from multiple dimensions. For this reason, preventing drop-outs from addiction treatment should be addressed with patient characteristics and treatment processes. Several studies showed that most of the drop-outs are are most often experienced in the first month of the treatment [Citation9]. This suggests that motivation-enhancing interventions, the changing environment in which the person is living, and establishing therapeutic alliance with the patient can be effective in preventing the drop-outs. Since the first month of the treatment is the peak period in which patients have severe desire for alcohol/ substance use, it is also considered as a risk factor for adversely affecting the continuation of treatment [Citation10]. Some studies also reported that female patients have higher drop-out rates compared to the male patients [Citation11].

Addiction is a chronic disease and achieving a full remission is quite challenging. Decrease in alcohol/ substance use, increase in psychosocial functioning, improvement in psychological problems are considered as recovery in addiction treatment. When all these dimensions are addressed, improvement in addiction treatment is only possible with staying in the treatment [Citation12]. Drop-out from the addiction treatment has been the subject of much research to date but these studies mostly mentioned the risk factors that are linked to treatment processes, but they did not pay attention to the effects of the individual relationships of the patient as a predictive factor. Considering the addiction as a family disorder and involving the family members in the treatment process would have a positive effect on recovery [Citation13] as well as a preventing the treatment drop-outs. In addition to the individual benefits for the patients, there are many social and financial gains of completion of an addiction treatment [Citation14].

Higher drop-out rates would increase the likelihood of the relapses and negative outcomes for the patients in terms of physical, social, and legal aspects. Understanding the risk factors for drop-out behaviour would contribute to the correct use of resources allocated for treatment, the reduction in the mortality rates due to alcohol/ substance use, and the development of individualized treatment modalities in addiction rather than the uniform treatment models that fit all. In this study, we aimed to examine the reasons of drop-out behaviour in outpatients with alcohol or/and substance use disorder who presented to an addiction counseling centre in Istanbul, Turkey.

Methods

Study participants

This study was conducted in outpatients with alcohol or/and substance use disorder who presented to the Turkish Green Crescent Counseling Center (YEDAM) for addiction treatment in Istanbul, Turkey. 554 outpatients who presented to the YEDAM between January 2016 and June 2017 were evaluated retrospectively. The participants were selected from the patients who had not any psychotic disorders and accepted the treatment in this centre. The sociodemographic characteristics of the patients were presented in .

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of the participants and their number of drug use cessation attempts.

The study received ethical approval from Hasan Kalyoncu University Social Sciences Institute Ethics Service (Reference Number: 2018/10, Date: 28.02.2018).

Information about the treatment programme

The Turkish Green Crescent Counseling Center (YEDAM) is a centre that gives free psychological and social support to outpatients with alcohol/ substance use disorder. Patients aged 16 years and over are accepted to the centre for treatment. Clinical evaluations were made at the baseline visit and the appropriate treatment programme was administered according to the substance use characteristics such as severity of dependence and comorbid diagnoses. The treatmet programme at the YEDAM consists of weekly individual psychotherapy sessions, homeworks, family sessions, and psycho-education group therapy sessions. Individual therapies are consisted of mostly Cognitive–Behavioral Therapies, Motivational Interviews, and Mindfulness Therapies. In psycho-educational group sessions, the SAMBA treatment programme has been administered to both patients and their families [Citation15]. The SAMBA treatment programme is a structured programme implemented by the trained psychologists.

Psychometric measurements

The data have been extracted by using the YEDAMSOFT software system that is widely used in YEDAM centres and Addiction Profile Index (BAPI) included in this software system. There are five subscales. The subscales measure the characteristics of substance use, dependency diagnosis, the effect of substance use on the person’s life, craving, and the motivation for quitting using substances.

Addiction Profile Index (BAPI): The Addiction Profile Index (BAPI), developed by Ogel et al., is a self-report questionnaire that consists of 37 items to measure severity of the addiction and evaluate different charateristics of addiction [Citation16]. Each item is rated from 0 to 4 on a five-point Likert scale. The questionnaire consisted of five subscales, measuring the characteristics of substance use, criteria for addiction diagnosis, the effect of substance use on the person’s life, strong craving for the substance use, and the motivation for cessation of substance use. The subscale scores are calculated separately and the total score is obtained by averaging the subscales. The Cronbach’s alfa coefficient for the whole questionnaire is 0.89 and they range from 0.63 to 0.86 for the subscales.

The Addiction Profile Index Clinical Form (BAPI-K): The Addiction Profile Clinical Form (BAPI-K) is intended to be used in clinical practice in conjunction with the original 37- item scale, consists of 21 items [Citation17]. It aimed to measure factors related to addiction; anger management problems, lack of safe behaviour, excitement seeking behaviour, impulsive behaviour, and depression and anxiety related factors that would lead to addictive behaviour. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of this scale was found to be 0.80 and the subscales ranged from 0.66 to 0.75. When all questions that directly measured addiction, from all sections of the scale, were added to the analysis, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the total scale was found to be 0.81. Four factors was obtained according to the explanatory factor analysis and these 4 factors represented the 53% of the total variance. The first factor consisted of depression and anxiety related items. The second factor consisted of anger management problems and impulsivity items and the third one had items about lacking safe behaviour, and the fourth factor had items about excitement seeking behaviour. When compared to analyses that were performed using other tests, it was determined that the subscales of the questionnaire showed strong correlations. The sociodemographic data were extracted from the questions in the BAPI form included in the YEDAMSOFT software [Citation15]. Economical status and family relations have been assessed by an analogue scale and higher scores mean the severity of the problem.

Statistical analysis

The patients who did not come to any session after the last session are regarded as drop-out from the treatment. Since the frequency of the sessions and the duration between the sessions were different, the number of the sessions were evaluated in this study. In order to ensure ease of expression and cross-sectional assessment while calculating treatment drop-out rates, the cases from the 2nd, 5th, and 10th sessions were evaluated. Patients who were literate and graduated from elementary or middle schools are categorized as low educational status; patients who graduated from high school or college were grouped as high educational status. For the marital status; patients were divided into two groups; single or married. Number of attempts to quit are categorized as; None, 1–3 times, 4–9 times, 10 and more times. Psychiatric treatment history is categorizedas; None, 1 time, 2–3 times, 4 times and more. Student t-test and chi-square analysis were performed to compare the patients who dropped-out and who did not. Since there are many factors that have influence on drop-out from addiction treatment, these variables are categorized and models were determined. Variables such as gender, age, marital status, employment status, family status, and economical status are grouped under the sociodemographic category; substance use characteristics, substance use desire, frequency of substance use, motivation, and attempt to quit substance ise were grouped under the addiction features category. For more detailed analyses, the BAPI subcales were analyzed instead of BAPI total scores. Since most of the patients were using synthetic cannbinoid, drop-out reasons were not analyzed depending on the substance of choice. The variables that may effect the addiction process like depression, anxiety, impulsivity, excitement seeking behaviour, anger control problems, lack of safe behaviour were categorized as psychological problems. A logistic regression analysis was performed to examine the factors predictive for drop-out from addiction treatment. The duration time of the patients between 2nd and 10th sessions were analyzed by using Kaplan-Meier Survival Analysis and prognostic factors were analyzed by using the Cox Regression Analysis.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics and the characteristics of the number of cessation attempts of the patients who completed or did not complete the treatment were presented in the Tabel 1. The mean age of the participants was 28.06 ± 7.89 and most of them were male. Two third of the participants were just literate. Most of the participants were single. 20.7% of the participants had irregular jobs, 38.8% of the participants were unemployed. 18.4% of the participants did not have any cessation attempts before and 9.9% of the paticipants had 10 times or more cessation attempts. When we look at the relationship with the parents, relationships with father were determined as negative. 42.6% (n = 158) of the participants were synthetic cannabinoid users, 10.8% (n = 40) of them were cannabis users, 21.8% (n = 81) of them were heroin users, 16.4% (n = 61) of them were alcohol users, and 8.4% of them used other subtances.

The drop-out rate of the participants after the 2nd session was 42.5%. After the 5th session it reached to 78.2%, and after the 10th session it reached to 93.9%. The highest drop-out rate was observed after the second session. When all the interviews were completed, it was found that male patients had higher drop-out rates than female patients (). While statistically insignificant, male patients were 2.8 times more likely to drop-out from the treatment compared to the female patients [CI = 1.01–7.81]. Patients with low educational level were three times more likely to drop-out than the patients with higher educational level [CI = 1.54–7.13]. There were no statistically significant differences between employment status and treatment drop-out rates. There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups in terms of numbers of cessation attempts. Similarly, the relationship scores with the mother were not different between those who dropped-out of the treatment and those who did not. Patients who dropped-out of treatment had higher scores of negative relationship with their fathers compared to the patients who continued the treatment (p = 0.02). When the BAPI subscales were evaluated, it was noted that the motivation factor was significantly higher in patients who continued to the treament (p = 0.02). When factors predicting treatment drop-out rates after the 2nd session were evaluated; while no significant predictive factor was found within the model sociodemographic characteristics, severe substance desire and being under probation order were found significanlty predictive of the drop-out behaviour within the model of substance use characteristics, and previous psychiatric treatment and excitement seeking behaviours were found significanlty predictive of the drop-out behaviour within the model of psychological problems (). When factors predicting treatment drop-out rates after the 5th session were evaluated; education level, marital status, and relationship with father were significant predictive factors within the model of sociodemographic characteristics, adverse effects of sustance use and being under probation order were found significanlty predictive of the drop-out behaviour within the model of substance use characteristics, and previous psychiatric treatment was found significantly predictive of the drop-out behaviour within the model of psychological problems. Patients who were under probation order were 6.40 times more likely to drop-out than who were not under probation order [CI = 1.55–26.43]. Previous psychiatric treatment was found to be predictive factor for drop-out after both the 2nd and 5th sessions. Age and gender factor among the sociodemographic characteristics, being under the probation order among the substance use characteristics were found predictive factor for drop-out from treatment after the 10th session. No significant factor was found predictive of drop-out behaviour among the psychological problems.

Table 2. Comparison of sociodemographic and substance use characteristics and psychological problems of the patients who drop-out and who continue the treatment.

Table 3. Predictive factors for treatmet drop-out behaviour according to regression analysis.

Duration of treatment for the patients was assessed by Kaplan-Meier survival analysis. Survival time of the patients was obtained by calculating the first session and the last session that the patient dropped-out after and it is revealed that time of attrition differed for stages of treatment. It is found that mean visit at loss was 2.8 for the interval between first and tenth visits while it was 4.8 for second to tenth. (CI = 2.58–2.98). It was found that the patients dropped-out after the 4.24. session from the 2nd to the 10th session (CI = 3.98–4.51). When the variables associated with treatment drop-out rates were assessed by Cox’s Regression Analysis, psychiatric treatment history and excitement seeking behaviour were found as significant factors in treatment drop-out behaviour (95% confidence interval, p < 0.05) (). In order to test the proportional hazards assumption of the Cox Regression Model, log minus log plot is conducted by each variable and the analogy of the variables are tested visually, so that it is seen a parallel graph is drawn.

Table 4. Variables predicts drop-out according to cox regression analysis results.

Discussion

This study is a retrospective, chart review study conducted on outpatients who applied to the Turkish Green Crescent Counselling Center between January 2016 and July 2017 for alcohol and/ or substance use disorders. 554 patients are evaluated at second, fifth and tents follow-up visits with Addiction Profile Index (BAPI) and Addiction Profile Index- Clinical Form (BAPI-K).

In this present study, the highest treatment drop-out rate has been observed after the second session. In male patients; low education status, being single, negative relationship with father, adverse effects of substance use, severe substance use desire were found to be predictive factors for drop-out behaviour. In addition, low motivation, being under probation order, previous psychiatric treatment history were also associated with higher drop-out rates in male patients.

The predictive factors were found to be dependent on the session that the drop-out has been actualized. The factors that caused the drop-out in the 2nd session were severe substance desire, being under the probation order, previous psychiatric treament history, and excitement seeking behaviour. The factors that caused the drop-out in the 5th session were educational and marital statuses, adverse effects of the substance use, being under the probation order, and previous psychiatric treament history. Age, educational status and being under the probation order were found as predictive factors for drop-out after the 10th session.

In studies examining the drop-out factors in addiction teatments, age was found to be an important factor [Citation18]. Age factor was also found to be one of the reasons for the cessation of treatment in the later stages of addiction treatment. In meta-analytic studies, motivation factor has been found to be effective in addiction treatment [Citation7]. In this present study, it was shown that higher motivation allowed patients to stay in the treatment longer. Studies evaluating structured programmes showed that the patients who had severe substance desire had problems in completing the addiction treatment programmes [Citation19,Citation20]. In this present study, we also found that substance use desire in the first stages of treatment was a predictive risk factor for drop-out behaviour.

In the current literature, there are studies with different results about the effect of depression comorbidity on addiction treatment drop-out. While some studies suggested that the depression was an important risk factor for treatment drop-out, especially in the begining of the treatment process [Citation21], there are also other studies showed that patients with depressive symptoms stayed longer in the treatment and did not drop-out in the begining of the treatment process [Citation22]. In this present study, no relationship between depression and drop-out or continuity of the treatment has been found. However, excitement seeking behaviour which has not been examined in previous studies has been found as a predictive factor for treatment drop-out behaviour in this present study.

While it has been reported that female patients have higher drop-out rates compared to the male patients in the current literature [Citation23]; in this present study, male patients showed higher treatment drop-out rates compared to the female patients. This result might be intepreted within the context of intercultural differences on treatment drop-out rates. For this reason, treatment strategies should be re-structured according to the sociocultural characteristic differences.

In this present study, since the drop-out reasons may vary depending on various stages of addiction treatment, we aimed to examine the reasons of treatment drop-out prior to the 2nd session as the first step of tretment and after the 5th and 10th sessions. In the literature most of the drop-outs has been observed during the initial stages of the treatment and our results were consistent with this finding. The studies that examined the drop-out reasons during the intial stages of addiction treatment showed that low educational status, number of arrests, previous treatment history had effects on drop-out rates [Citation24]. In this present study, same factors were also found to be the predictive factors for drop-out after the 5th session. When we combine these results with the literature, the first five sessions can be conceptualized as the first step of the treatment.

This study has certain limitations. First, studies showed that sociodemogaphic characteristics, substance use features, psychological problems, and therapeutic relationship between the patient and the therapist are the predictive factors for treatment drop-out behaviour [Citation7]. In this present study, only the factors related to the patient has been evaluated and the relationship between the patient and the therapist has not been examined. Besides, since participants’ answers are based on analog scale, it would not have been possible to gather detailed information about family relations. Second, the treatment programme has been supposed to be a standard programme, therefore the drop-out reasons were examined dependent on the variables and the differences between the psychologists and treatment forms have not been examined. One of the limitations of the study is the co-morbid psychiatric disorders are not well defined. In the future studies, it would be important to define and categorize co-occuring psychiatric disorders to understand the relationship between these disorders and drop-out. As the current study is a retrospective chart study, only BAPI and BAPI-K scales which are already used in clinical practice, are applied. This is also another limitation of the study.

In addition to patient-related factors, how the treatment programmes have been administered and therapeutic relationship between the patients and the therapists should be examined as well. Last, 42.6% of the participants were cannabinoid users. It has been known that syntetic cannabinoids might cause impairments in cognitive functions [Citation25]. Since the majority of the participants were cannabionid users, cognitive impairments might have played a significant role on the drop-out behaviour as well. Therefore, cognitive features of the participants should be evaluted in the future studies. Furthermore, our participants consisted of outpatients in a psychosocial supportive programme. Studying drop-out factors in inpatients would provide a comparison for the drop-out factors between the two treatment settings.

Evaluating the factors that causes drop out from the treatment will support in improving the addiction treatment services and developing specific treatment strategies. Evaluating the factors that causes drop-out from addiction treatment will provide additional benefits such as decreasing the crime rates and correct use of the resources allocated for the patients. Studying these factors will decrease the mortality rates and contribute to the development of individualized treatment modalities for addiction rather than the uniform treatment modalities ().

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Deane FP, Wootton DJ, Hsu CI, et al. Predicting dropout in the first 3 months of 12-step residential drug and alcohol treatment in an Australian sample. J Stud Alcohol Drug. 2012;73(2):216–225. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2012.73.216

- McKellar J, Kelly J, Harris A, et al. Pretreatment and during treatment risk factors for dropout among patients with substance use disorders. Addict Behav. 2006;31(3):450–460. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.05.024

- Gilchrist G, Langohr K, Fonseca F, et al. Factors associated with discharge against medical advice from an inpatient alcohol and drug detoxification unit in Barcelona during 1993–2006. Heroin Addict Rel Cl. 2012;14(1):35–44.

- McHugh RK, Murray HW, Hearon BA, et al. Predictors of dropout from psychosocial treatment in opioid-dependent outpatients. Am J Addict. 2013;22(1):18–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2013.00317.x

- Samuel DB, LaPaglia DM, Maccarelli LM, et al. Personality disorders and retention in a therapeutic community for substance dependence. Am J Addict. 2011;20(6):555–562. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2011.00174.x

- Agosti V, Nunes E, Ocepek-Welikson K. Patient factors related to early attrition from an outpatient cocaine research clinic. Am J Drug Alcohol Ab. 1996;22:29–39. doi: 10.3109/00952999609001643

- Baekeland F, Lundwall L. Dropping out of treatment: A critical review. Psychol Bull. 1975;82(5):738–783. doi: 10.1037/h0077132

- Craig RJ. Reducing the treatment drop out rate in drug abuse programs. J Subst Ab Treat. 1985;2(4):209–219. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(85)90003-0

- King AC, Canada SA. Client-related predictors of early treatment drop-out in a substance abuse clinic exclusively employing individual therapy. J Subst Ab Tr 2004;26(3), 189–195. doi: 10.1016/S0740-5472(03)00210-1

- Bottlender M, Soyka M. Impact of craving on alcohol relapse during, and 12 months following, outpatient treatment. Alcohol Alcoholism. 2004;39(4):357–361. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agh073

- McCaul ME, Svikis DS, Moore RD. Predictors of outpatient treatment retention: patient versus substance use characteristics. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2001;62(1):9–17. doi: 10.1016/S0376-8716(00)00155-1

- Simpson DD. The relation of time spent in drug abuse treatment to posttreatment outcome. Am J Psychiatr. 1979;136(11):1449–1453. doi: 10.1176/ajp.136.11.1449

- Copello AG, Copello AG, Velleman RD, et al. Family interventions in the treatment of alcohol and drug problems. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2005;24(4):369–385. doi: 10.1080/09595230500302356

- Fernandez-Montalvo J, López-Goñi JJ. Comparison of completers and dropouts in psychological treatment for cocaine addiction. Addict Res Theory. 2010;18(4):433–441. doi: 10.3109/16066350903324826

- Ögel K. AlkolveMaddeBağımlılığıTedavisindeBireysel-leştirilmişTedaviPlanıOluşturacak Web TemelliBirAr-acınGeliştirilmesi. TÜBİTAK 1002 AraştırmaProjesi-Raporu, Proje No: 113S050, 2014; 25–26. [Turkish]

- Ogel K, Evren C, Karadag F, et al. Development, validity and reliability study of addiction profile index (BAPI). Türk Psikiyatri Dergisi. 2012;23:264–273. [ Turkish].

- Ogel K, Koc C, Basabak AZ, et al. Development of addiction profile index (BAPI) clinical form: reliability and validity study. Bağımlılık Dergisi. 2015;16(2):57–69. [ Turkish].

- Brorson HH, Arnevik EA, Rand-Hendriksen K, et al. Drop-out from addiction treatment: a systematic review of risk factors. Clin Psychol Rev. 2013;33(8):1010–1024. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.07.007

- Ögel K, Bilici R, Bahadır GG, et al. Denetimli serbestlikte, sigara, alkol madde bağımlılığı tedavi programı (SAMBA) uygulamasının etkinliği. Anadolu Psikiyatri Derg. 2016;17:270–277. [ Turkish]. doi: 10.5455/apd.200521

- Bilici R, Ögel K, Bahadır GG, et al. Treatment outcomes of drug users in probation period: three months follow-up. Psychiatr Clin Psychopharm. 2018;28(2):149–155.

- Curran GM, Kirchner JE, Worley M, et al. Depressive symptomatology and early attrition from intensive outpatient substance use treatment. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2002;29(2):138–143. doi: 10.1007/BF02287700

- Levin FR, Evans SM, Vosburg SK, et al. Impact of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and other psychopathology on treatment retention among cocaine abusers in a therapeutic community. Addict Behav. 2004;29(9):1875–1882. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.03.041

- Arfken CL, Klein C, di Menza S, et al. Gender differences in problem severity at assessment and treatment retention. J Subst Ab Treat. 2001;20:53–57. doi: 10.1016/S0740-5472(00)00155-0

- Claus RE, Kindleberger LR, Dugan MC. Predictors of attrition in a longitudinal study of substance abusers. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2002;34(1):69–74. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2002.10399938

- Crean RD, Crane NA, Mason BJ. An evidence based review of acute and long-term effects of cannabis use on executive cognitive functions. J Addict Med. 2011;5(1):1–8. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e31820c23fa