ABSTRACT

The purpose of the paper is an empirical verification of model of the cohesive management for business organizations. The cohesive management concept is a particular type of management carried out in top European football clubs. Football clubs are characterized by their far-reaching agility, operate in an extremely competitive reality (the winner takes all!), where success depends on the commitment of highly diverse talents from all over the world. Extensive literature research provided a basis for operationalizing the dimensions of cohesive management (CM) in relation to business. The hypothetical model of the CM was verified by empirical research conducted in 406 companies from Poland and the USA. Research models were tested using SEM and moderated multiple regression. The study revealed that what works in top team football is not outdated in relation to business management (CM structure was confirmed); however, it is impossible to mechanically transfer the solutions developed there (significant changes in CM dimension structures were noted). The study demonstrates the importance of CM for organizational performance, whereby the impact is significantly higher in high-tech organizations.

1. Introduction

Management theory, due to its social nature, is constantly evolving. Some time ago, Drucker suggested that the best model of a new type of organization fitted to knowledge era conditions is the orchestra, in which the professional musicians harmoniously cooperate with each other, as if they were one organism (Drucker & Wartzman, Citation2010). However, the metaphor of the orchestra has the main disadvantage that the musicians repeatedly play with the same notes, often written many years ago. Moreover, other orchestras do not interfere with the game, musicians during a performance do not have to change the way they act and interact depending on the behaviour of competing orchestras. Today's reality, is still characterized by a reliance on professionals with in-depth expertise and specific skills, often unavailable to others. However, achieving great results nowadays requires not only highly committed professionals working together, but workforce arranged in the most flexible way facing temporary and to some extend unique, unpredictable and time bound business challenges (George et al., Citation2016). As a result, the workforce diversity and volatility in modern organizations, is becoming the norm (Bosch-Sijtsema et al., Citation2009; Chambers et al., Citation1998). This is not only because of uniqueness and temporality of tasks, but because professionals are more committed to profession and personal development rather than to the organization, and also the work provision is more independent form physical location (geographical mobility of employees increases) (Morawski, Citation2003; Pyöriä, Citation2005). Finally, there is an increasingly intense, ruthless and global talent competition (Chambers et al., Citation1998; Farndale et al., Citation2010; Sparrow et al., Citation2017; Vaiman et al., Citation2012). Such conditions are inherent in the high-tech industry (Hopej & Kandora, Citation2019).

The model of organization ready to meet such challenges is more like football club than orchestra. Football clubs are characterised by their far-reaching agility, operate in an extremely competitive reality (the winner takes all!), where success depends on the commitment of highly diverse talents from all over the world (Bolchover & Brady, Citation2006; Kuper & Szymanski, Citation2017; Mościcki, Citation2019). This assumption has stimulated work on a particular type of management carried out in top European football clubs, recognized as a cohesive management, a management focused on supporting diversity and using it to achieve excellent results (Hopej & Kandora, Citation2019). The extensive literature research was also conducted to define and operationalize the dimensions of cohesive management in relation to business organizations by grounding them in management science theory (Zgrzywa-Ziemak et al., Citation2022). However, there is no empirical verification of the model of cohesive management.

The main purpose of the paper is an empirical verification of the model of the cohesive management for business organizations. The current study addresses three main research questions:

RQ1. What is the structure of the cohesive management phenomenon for a business organisation (empirical verification)?

RQ2. What effect does the cohesive management have on organisational performance?

RQ3. What is the impact of technological advancement on the effect of cohesive management on organisational performance?

2. The concept of cohesive management

Based on the management of top football clubs analysis (Bolchover & Brady, Citation2006; Kuper & Szymanski, Citation2017; Mościcki, Citation2019), cohesive management (CM) concept was developed as management focused on integrating the activities of diverse members of the organization, arranged in the most flexible way for success of temporary and to some extend unique business challenges (Hopej & Kandora, Citation2019). Four main dimensions of CM were identified: game for talent, sense of unity of purpose, shared identity and transparency of operations (Hopej & Kandora, Citation2019; Zgrzywa-Ziemak et al., Citation2022).

The success of football clubs, meaning winning more and more games, depends mainly on the players they have managed to recruit (Kuper & Szymanski, Citation2017). The search for the most talented footballers is part of an ongoing game (even war) among the top clubs for football talents.Footnote1 It is emphasized that the activities of the talent cycle management are at present almost free of various prejudices, including those related to racial aspects. Although, the diversity of players is significant (in terms of their race, nationality and age, among other factors), the recruitment of talents is not done under the banner of diversity (Kuper & Szymanski, Citation2017; Zgrzywa-Ziemak et al., Citation2022).

However, as A. Ferguson, a long-time Manchester United manager, comments ‘I have never been interested in simply sending out a collection of brilliant individuals. There is no substitute for talent but, on the field, talent without unity of purpose is a hopelessly devalued currency’ (Bolchover & Brady, Citation2006, p. 210). The players of top football clubs are distinguished by the fact that on the pitch, and to some extent outside it, they are unified by a sense of the unity of a common purpose. The formation of a sense of unity of purpose requires that this purpose be clearly formulated so that players work together to achieve something significant. Moreover, it is necessary to respect the classical principle of subordinating the personal interest to the general interest (Hopej & Kandora, Citation2019). B. Shankly, the former Liverpool FC manager, argues ‘(…) the way to live and be truly successful is by collective effort, with everyone working for each other, everyone helping each other, and everyone having a share of the rewards at the end of the day’ (Critchley, Citation2018, p. 9).

J. Klopp, FC Liverpool coach, implements also the effective unification of footballers by means of organizational culture. He requires them to do the same: respect him, the team and what they try to accomplish. His players must commit to a shared value system that includes: unconditional commitment, a passionate obsession, de-termination, no matter which way the game goes, willingness to support everyone without exception, willingness to seek help, a commitment to contribute 100% effort for the good of the team, and personal responsibility (‘Wygrywaj jak Jürgen Klopp* | neocichociemni’, in press). A shared identity results from focusing on what footballers have in common rather than what divides them. The existing differences between them are then, to some extent, bridged or drowned in a sea of similarities.

There is also the final issue. Football is highly transparent. The transparency and openness of the activity, which in football is not a groundless declaration, is primarily due to the relentless media attention (Bolchover & Brady, Citation2006). Almost no detail escapes the cameras’ attention; everything is repeated, commented on and counted in the statistics.

On the one hand, the CM concept seems to clearly meet the challenges of modern organizations, especially high-tech organizations. On the other, the extensive management literature review does not offer proposals that simultaneously take into account all four dimensions recognized as crucial for football clubs management. Zgrzywa-Ziemak et al. (Citation2022) conducted literature research to define and operationalise the dimensions of CM in relation to business, and they developed the hypothetical model of the CM. provides the main results of an extensive literature research aiming to define and operationalise the dimensions of CM in relation to business organizations in accordance with management science theory.

Table 1. The model of CM: football lesson.

Although the CM model for football clubs appears consistent, not all of its characteristics have received explicit confirmation in the literature in the field of management theory (e.g. workforce management issue). However, the empirical study confirmed, following Zgrzywa-Ziemak et al. (Citation2022), a hypothetical CM model specific to football. includes the main research hypotheses and the detailed ones related to the structure of CM dimensions.

Table 2. Hypothetical model of the cohesive management.

Two more research hypotheses were developed to explore the effect of cohesive management on organizational performance.

A distinguishing feature of management science is its focus on effectiveness, so it is necessary to examine whether CM that has been recognized as effective in football clubs is also effective in business organizations. Two further research hypotheses were developed to investigate the impact of consistent management on organizational performance. A distinguishing feature of management science is its focus on effectiveness, so it is necessary to examine whether CM that has been recognised as effective in football clubs is also effective in business organizations. Hypothesis H5 is therefore formulated: The cohesive management positively effects organizational performance.

Referring to the assumption formulated and theoretically justified in the introduction, CM is a type of management particularly dedicated to organizations operating in conditions specific to high-tech industries. However, this assumption requires verification. Accordingly, hypothesis H6 is posited: The technological advancement influences the strength of the relationship between cohesive management and organizational performance (so it is a moderator).

3. The empirical verification of the cohesive management model

3.1. Research method

The empirical verification of the hypothetical cohesive management (CM) model was carried out on the basis of a questionnaire survey. The research tool was a questionnaire and the methods of description and statistical inference were used to analyse the empirical data.

The questionnaire included questions related to the individual dimensions of cohesive management (a total of 12 items), organizational performance (13 items) and selected characteristics of the research objects (employment size, the predominant type of the organization’s activity, the range of activity and technological advancement). At the beginning of the questionnaire, the purpose of the study was presented and the anonymity of the answers was assured. At the end, a thank-you note for participating in the study was attached. In order to verify the relevance of the items included in the questionnaire, the authors decided to use the method of competent judges, which was already employed at the stage of its development. The judges, who were academics, senior managers and statisticians, independently scored each questionnaire item.

Due to the nature of the CM phenomenon, it was considered that any organization could be included in the study. Therefore, the questionnaire prepared was addressed to different organizations in terms of the type of activity, size and form of ownership. It was only assumed that some characteristics of the phenomenon could not be observed in too small enterprises. Therefore it was decided to include in the survey enterprises employing more than nine persons (thus, micro-enterprises were rejected). The study was conducted in the organizations operating in Poland and the United States – in the countries that differ in many respects (culture, legal regulations, business traditions). In each country, respondents filled out the questionnaire in their native language – in Poland in Polish, and in the US in English. The study was carried out by two professional organizations dealing with this type of research – SurveyMonkey (in the USA) and Biostat (in Poland). The questionnaire is addressed to a senior manager or another person having a broad view of the whole company (it was considered that such a person, in addition to the president and his/her deputy, may be, for instance, an organizational specialist, business process management specialist, quality specialist etc.). The study was carried out in 2020.

A total of 406 companies were surveyed (): 182 (44.83%) operating in Poland and 224 (55.17%) from the USA. A balanced sample was obtained in terms of size and technological advancement; however, the sample was differentiated in terms of the type of activity. At the same time, these characteristics are typical of the whole sample but not of individual countries: Poland was dominated by small and medium-sized enterprises with low technological advancement, mainly in services, while in the United States, mainly large and very large enterprises with high technological advancement, manufacturing and services, were examined.

Table 3. Structure of the research sample in terms of selected characteristics.

The primary statistical methods were Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) and moderated multiple regression. All analyses were performed by means of the PS IMAGIO software while multi-dimensional modelling was performed in AMOS 26.0.0.

3.2. Measuring the dimensions of the cohesive management

Starting from the research hypotheses (), the authors determined the variables comprising the structure of each dimension. Then, these variables formed the basis for the formulation of the individual items of the measurement tool. The CM dimensions, the variables constructing these dimensions and the individual items in the questionnaire are included in . On a five-point scale, the respondents subjectively rated the extent to which each statement describes their organization. The consistency of the scales of the different dimensions of the cohesive management was verified. Descriptive statistics and measures of scale reliability are included in Appendix 1 and 2.

Table 4. Cohesive management: dimensions, variables and scale items.

It was decided that the model would include:

the dimension Game for talent. The dimension is constructed by three variables but the variable Orientation to workforce diversity entered the model with an inverted scale;

the dimension Sense of unity of purpose was consistent with the theoretical assumptions;

the dimension Shared identity (one item, as intended);

in the case of the dimension Transparency of operations, the variable Managers’ trust in simplicity was excluded from the scale (together, the variables did not build a coherent scale).

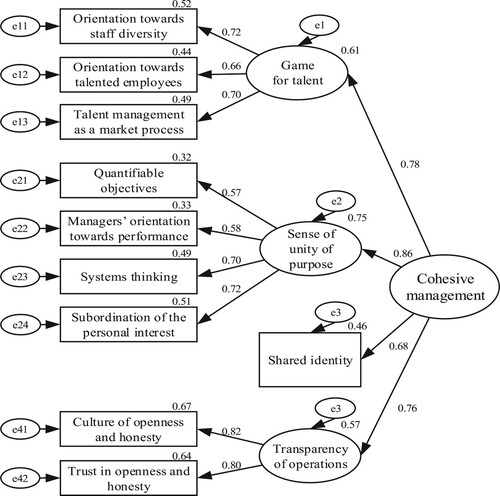

3.3. An empirical model of the cohesive management

A confirmatory factor analysis model (Model-1_CM) was constructed. We used the Asymptotically Distribution-free Estimates Method, which does not require a multivariate normal distribution. The final model is presented in . The model is well adjusted to the data due to key measures of such adjustment: Χ2 (32) = 73.592, p < 0.001, Χ2/df = 2.300, GFI = 0.959, AGFI = 0.930, RMSEA = 0.057, RMR = 0.062. All estimated parameters are significant (p < 0.001).

According to the assumptions, the structure of CM is constructed by four factors (, ). The most considerable contribution to the structure of the cohesive management is Sense of unity of purpose. The share of the next two factors in the structure of the researched phenomenon – Game for talent and Transparency of operations – is similar. The dimension of Shared identity contributed the least.

Table 5. Model-1_CM: standardized regression weights.

Although all four main hypotheses regarding the structure of CM should be accepted, at the same time, the structure of the different dimensions is not compatible with the expectations. addresses the individual research hypotheses.

Table 6. CM – verification of research hypotheses.

Hypothesis H1 was confirmed as the dimension Game for talent was found to be significant in the structure of CM. All three dimensions building the variables have comparable contributions. However, it was assumed that the game for talent required explicitly targeting human resource management processes at talent and rejecting other criteria, including those related to various aspects of workforce diversity. We interpret the result to mean that the game for talent must be accompanied by the acceptance of the diversity of employees.

Hypothesis H2 was confirmed and the Sense of unity of purpose dimension entered the CM structure, as it had been theorized. The sense of unity of purpose is constructed primarily by practicing systems thinking and the principle of subordinating the personal interest to the general interest. Less significant in the dimension structure, although statistically significant, was the quantification of the organization’s objectives and the association of managers’ evaluation with the performance of their subordinates.

The dimension of a shared identity, meaning that shared values and group identity are manifested in the organization, is a significant factor in the structure of CM – so hypothesis H3 was confirmed.

Finally, CM is shaped by the Transparency of business operations (hypothesis H4 should be confirmed). Theoretically, it was assumed that this dimension would include three aspects: managers’ trust in simplicity, a culture of openness and honesty and trust in openness and honesty within the organization. Finally, trust in simplicity was found to be insignificant both as a variable in the dimension and as a separate variable in the structure of the overall CM.

The study assumed that CM would have a positive impact on organizational performance. Therefore, hypothesis H5 was formulated: ‘The cohesive management positively impacts organizational performance’.

4. Cohesive management and organizational performance

Due to the increasing pressure to go beyond a purely economic concept of performance, in this study, the measurement of organizational performance is concerned with integrated economic, social and environmental performance (sustainable performance). The Sustainable performance variable is constructed by three dimensions and the items included in each dimension are included in . The economic dimension includes measuring financial and non-financial economic performance (Maletič et al., Citation2016; Matić, Citation2012). Social performance refers to the extent to which the organization makes a positive contribution to healthy and livable communities (Crane et al., Citation2014; Vallance et al., Citation2011). Environmental performance refers to the impact of the organization’s activities on the environment in terms of resource use and emissions as well as waste generation (Campos et al., Citation2015; Matić, Citation2012). Respondents subjectively rated individual performance categories against competing companies on a five-point scale. The aggregate variable Sustainable performance was created by averaging the three variables relating to the different performance groups. The consistency of the scale of each dimension and the aggregate variable was verified (Appendix 1). For the environmental dimension, one item was excluded from the scale (‘environmental impacts of the products or services sold over their entire life cycle’).

Table 7. Sustainable performance: variables and scale items.

As a result, both the Sustainable performance variable and the individual performance dimensions have consistent scales. Appendix 2 provides descriptive statistics for the organizational performance variables.

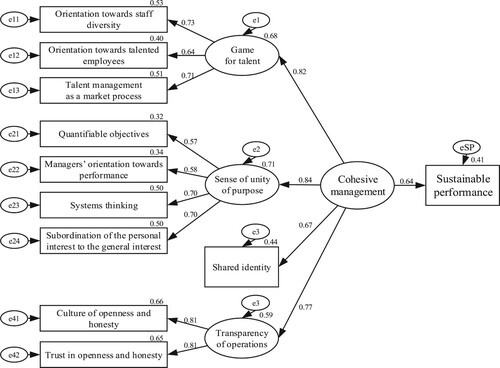

A structural model – Model-2_CM-OP () – was developed to determine the relationship between the cohesive management and organization’s performance. The model is well adjusted to the data due to the key measures of such adjustment Χ2 (41) = 88.538, p < 0.001, Χ2/df = 2.159, GFI = 0.956, AGFI = 0.929, RMSEA = 0.054, RMR = 0.061. All estimated parameters are significant (p < 0.001).

Figure 2. Model-2_CM-OP: a structural model of the relationship between the cohesive management and sustainable performance (n = 406).

The model indicates the significant impact of the cohesive management on overall organizational performance. More than 40% of the variation in sustainable performance is explained by the cohesive management (the multiple correlation coefficient R2 is 0.41).

5. The technological advancement as a moderator of cohesive management and organizational performance relationship

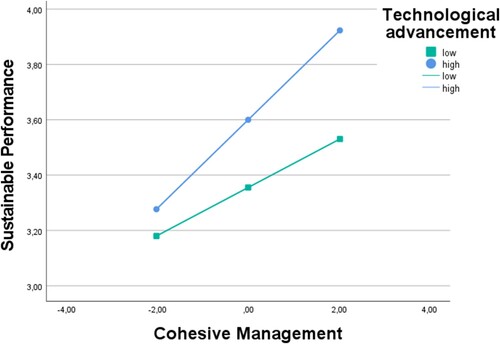

The Hayes Process macro to perform moderated multiple regression was used, to verify whether the technological advancement influences the strength of the relationship between CM and SP (so it is a moderator). includes the results of the analysis ().

Table 8. Model-3_CM-OP-AT: moderated multiple regression results.

The effect of CM on SP is positive and significant (b = 0.1259, s.e. = 0.0112, p < 0.001), conditional on TA = 0, the effect of TA is positive and significant (b = 0.2447, s.e. = 0.0453, p < 0.001), conditional on CM = 0. The interaction term is statistically significant and positive (b = 0.0732, s.e. = 0.0226, p < 0.05) in the model, indicating that technological advancement is a significant moderator of the effect of CM on SP. The R-square change due to the moderation effect is low, 0.0164 (F (1,402) = 10.471; p < 0.05), indicating that the interaction effect accounted for only 1,64% added variation in sustainable performance (see ).

Figure 3. Model-3_CM-OP-AT: the technological advancement as a moderator of the relationship between cohesive management and performance.

To sum up, the hypothesis H6 is confirmed.

6. Conclusions

The study revealed that what works in top team football is not very different when it comes to business management. The confirmed hypotheses seem to indicate a relatively large potential for the transfer of management practices used in football to business. On the other hand, the mechanical transfer is highly problematic, as evidenced by the fact that the structure of the individual dimensions did not turn out to be as it was expected.

The original concept of cohesive management presented in this article is based on the results of the analysis of management activities carried out in the best football clubs, usually coping very well with a team of players who is diversified in many respects. It was assumed that its dimensions are the game for talent, a sense of unity of purpose, a shared identity and transparency and openness of operations. Since in the management of football clubs, the same problems associated with the management of modern dynamic enterprises arise, a rather extensive empirical study oriented to determine the capability of the organizations for this type of management was carried out. Some significant conclusions can be drawn.

Firstly, the empirically verified model of the cohesive management is shaped by four dimensions assumed theoretically. The most important dimension of CM is the sense of unity of purpose, which means first and foremost practising systems thinking in the organization and implementing the principle of subordinating the personal interest to the general interesting and only secondly ensuring the quantifiability of organizational goals and orienting managers towards the achievement of the results by their subordinates.

A particularly interesting result is related to the second most important dimension of CM – the game for talent. In line with theoretical assumptions, it was supposed that the orientation towards workforce diversity stands in opposition to attracting the most talented employees. However, research has shown that talent orientation and the market struggle to attract and retain talent in the organization must be accompanied by diversity orientation and, more specifically, hiring under the banner of diversity. We interpret this result to mean that in the pursuit of talents, it is necessary to be open to the diversity of the workforce. Only such an attitude makes it possible to discard extrinsic preferences or biases in favour of talents. With reference to Sternberg: ‘Functional abilities and qualities are usually independent of age, sex, religion, ethnic origin, hair colour, sexual orientation, family connections, social background and smoking habits’ (Sternberg, Citation2000, p. 133). Managers need to develop their understanding of workforce diversity to attract talents from the widest possible pool of candidates without bias and avoid singling out or discriminating against employees on the basis of their non-business related characteristics.

In the CM structure, the sense of unity of purpose and the game for talent are accompanied by the transparency of operations. This dimension was modified in relation to the theoretical assumptions. The concept of transparency in the literature is multifaceted. The research assumes that the manifestation of this transparency is the practice of a culture of honesty and openness in the organizations, the trust of employees in this openness and honesty, and managers’ trust in simplicity. Only the first two aspects were confirmed (the last one turned out to be statistically insignificant). This means that cohesive management requires openness and honesty in relations among organization members but is not significantly shaped by a desire to simplify the activity.

The cohesive management is further shaped by the manifestation of shared values and shared identity. Indeed, the dimension of shared identity has the smallest share in the CM structure, although it is statistically significant.

The empirical studies demonstrates the importance of CM for performance and the impact of CM on performance appeared to be significantly higher in high-tech organizations. It would be highly interesting to deepen the study by analysing selected case studies of organizations. Particularly suitable here would be high-tech companies, characterised by considerable workforce diversity, dependent on employees’ high qualifications and talents (professionals ready to change jobs, searching for new challenges and benefits quickly). This would deepen our understanding of the different dimensions of CM and, perhaps, reveal another dimension not included in the current model.

This study is part of a discussion on the relationship between workforce diversity and organizational performance. An analysis of the literature reports on this relationship shows that although the benefits of workforce diversity (rarely its adverse effects) are widely discussed, there is still no coherent theory describing the relationship in question (Carstens & De Kock, Citation2017; Guillaume et al., Citation2017; Tworek et al., Citation2020). What is particularly important, empirical research in this area is very limited, difficult to compare, often linking workforce diversity to performance through an intervening variable. Individual studies confirm a significant positive relationship between workforce diversity because of a selected trait of primary identity and organizational performance (Catalyst, Citation2004; Tworek et al., Citation2020). Others demonstrate the absence of such a relationship or that it is very weak (Bell et al., Citation2011; Hogan & Huerta, Citation2019; Schneid et al., Citation2015; Tworek et al., Citation2020). Not only do the empirical studies to date fail to provide clear confirmation of the importance of diversity for organizational performance but they are also characterised by relatively strong simplifications in the assessment of organizational performance, being based primarily on financial measures. Although not verifying a direct relationship between workforce diversity and organizational performance, this study demonstrates the importance of the cohesive management – management focused on benefiting from differences among organizational members on organizational performance. The transfer of diversity management practices used in football clubs, which successively attract talents from different parts of the world to organizational management, opens up a new approach to diversity and its importance for organizational performance.

Finally, the construct of the variable Sustainable performance includes integrated economic-social-environmental performance. This understanding of organizational performance can be defined as a manifestation of the business contribution to sustainable development (Zgrzywa-Ziemak & Walecka-Jankowska, Citation2021). The study proves that the relationship between CM and sustainable performance is positive and statistically significant. The results obtained may therefore contribute to the discussion on the problem of shaping business sustainability.

Limitations and future research directions

It is essential to underline that the study presented above has some limitations. After all, as rightly pointed out by Kuper and Szymanski (Citation2017), football clubs tend to function more as charities than enterprises. Moreover, the limited size of football clubs is not without significance. That is why solutions fitted to football clubs should be carefully adapted to business. A disadvantage of the present study is the non-representative research sample. This limits the generalisability of the study. However, this is due to the conscious assumption that it is crucial to obtain equally numerous groups of organizations in the sample for two different countries, in terms of the size of organizations, the degree of technological advancement and diverse activities in order to explore CM. Unfortunately, it was impossible to obtain appropriate sample characteristics for each country, which made it impossible to compare the developed models on a country-by-country basis. Therefore, the results obtained should be treated with caution, as they suggest certain phenomena rather than prove them, and the study should be extended to include purposefully selected enterprises in individual countries. The relationship tested in this study represents a snapshot in time. For this reason, further research could be a drawn-out study to see how changes in CM interact with organizational performance. The hypothetical model also needs further verification in different business (cultural, technological, structural, etc.) contexts. Finally, the line of research on the contribution of cohesive management in shaping business sustainability is particularly promising.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Football is one of the few industries that can effectively compete as there are many sellers and buyers who have access to information about the quality of the players they buy and sell. If the salary is too low, footballers move to another club. The better the player is, the better he earns (Hopej & Kandora, Citation2019).

References

- Adler, N. J., & Gundersen, A. (2007). International dimensions of organizational behavior. South-Western College Publishing.

- Ashforth, B. E., & Mael, F. (1989). Social Identity Theory and the Organization. The Academy of Management Review, 14(1), 20–39. https://doi.org/10.2307/258189

- Ashkenas, R., Siegal, W., & Spiegel, M. (2014). Mastering organizational complexity: a core competence for 21st century leaders. In R. Woodman, W. Pasmore, & A. B. Shani (Eds.), Research in organizational change and development (pp. 29–58). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Bell, S. T., Villado, A. J., Lukasik, M. A., Belau, L., & Briggs, A. (2011). Getting specific about demographic diversity variable and team performance relationships: A meta-analysis. Journal of Management, 37(3), 709–743. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206310365001

- Berggren, E., & Bernshteyn, R. (2007). Organizational transparency drives company performance. Journal of Management Development, 26(5), 411–417. https://doi.org/10.1108/02621710710748248

- Blader, S. L., & Tyler, T.R. (2009). Testing and extending the group engagement model: Linkages between social identity, procedural justice. Economic Outcomes, and Extrarole Behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(2), 445–464.

- Bolchover, D., & Brady, C. (2006). The 90-minute manager: Lessons from the sharp End of management. Pearson Education.

- Bosch-Sijtsema, P. M., Ruohomäki, V., & Vartiainen, M. (2009). Knowledge work productivity in distributed teams. Journal of Knowledge Management, 13(6), 533–546. https://doi.org/10.1108/13673270910997178

- Campos, L. M. S., De Melo Heizen, D. A., Verdinelli, M. A., & Cauchick Miguel, P. (2015). Environmental performance indicators: A study on ISO 14001 certified companies. Journal of Cleaner Production, 99, 286–296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.03.019

- Carstens, J. G., & De Kock, F. (2017). Firm-level diversity management competencies: development and initial validation of a measure. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 28(15), 2109–2135. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2015.1128460

- Catalyst. (2004). The bottom line: Connecting corporate performance and gender diversity.

- Chambers, E. G., Foulon, M., Handfield-Jones, H., Hankin, S. M., & Michaels, E. G. I. (1998). The war for talent. The McKinsey Quarterly, 3, 44–57.

- Clair, J. A., Beatty, J. E., & Maclean, T. (2005). Out of sight but not out of mind: Managing invisible social identities in the workplace. Academy of Management Review, 30(1), 78–95. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2005.15281431

- Collings, D. G., & Mellahi, K. (2009). Strategic talent management: A review and research agenda. Human Resource Management Review, 19(4), 304–313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2009.04.001

- Crane, A., Palazzo, G., Spence, L. J., & Matten, D. (2014). Contesting the value of “creating shared value”. California Management Review, 56(2), 130–153. https://doi.org/10.1525/cmr.2014.56.2.130

- Critchley, S. (2018). What We think about when We think about football. Profile Books Ltd.

- Daubner-Siva, D., Vinkenburg, C. J., & Jansen, P. G. (2017). Dovetailing talent management and diversity management: the exclusion-inclusion paradox. Journal of Organizational Effectiveness: People and Performance, 4(4), 315–331. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOEPP-02-2017-0019

- Drucker, P. (2006). F.: The practice of management. Harper Business.

- Drucker, P. F., & Wartzman, R. (2010). The Drucker lectures: essential lessons on management, society and economy. McGraw Hill Professional.

- Drucker, S. J., & Gumpert, G. (2007). Through the looking glass: Illusions of transparency and the cult of information. Journal of Management Development, 26(5), 493–498. https://doi.org/10.1108/02621710710748329

- Eisenhardt, K. M., & Sull, D. (2001). N.: strategy as simple rules. Harvard Business Review, 107–116.

- Farndale, E., Scullion, H., & Sparrow, P. (2010). The role of the corporate HR function in global talent management. Journal of World Business, 45(2), 161–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2009.09.012

- Gallardo-Gallardo, E., Dries, N., & González-Cruz, T. (2013). What is the meaning of ‘talent’ in the world of work? Human Resource Management Review, 23(4), 290–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2013.05.002

- George, G., Howard-Grenville, J., Joshi, A., & Tihanyi, L. (2016). Understanding and tackling societal grand challenges through management research. Academy of Management Journal, 59(6), 1880–1895. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2016.4007

- Guillaume, Y. R. F., Dawson, J. F., Otaye-Ebede, L., Woods, S. A., & West, M. (2017). Harnessing demographic differences in organizations: What moderates the effects of workplace diversity? Journal of Organizational Behavior, 38(2), 276–303. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2040

- Heinen, J. S., & O’Neill, C. (2004). Managing talent to maximize performance. Employment Relations Today, 31(2), 67–82. https://doi.org/10.1002/ert.20018

- Hogan, R., & Huerta, D. (2019). The impact of gender and ethnic diversity on REIT operating performance. Managerial Finance, 45(1), 72–84. https://doi.org/10.1108/MF-02-2018-0064

- Hopej, M., & Kandora, M. (2019). The Concept of Conjoined Management. In Z. Wilimowska, L. Borzemski, & J. Świątek (Eds.), Information Systems Architecture and Technology: Proceedings of 39th International Conference on Information Systems Architecture and Technology – ISAT 2018. ISAT 2018 (Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing Vol. 854, pp. 173–187). Cham: Springer.

- Hopej-Kamińska, M., Zgrzywa-Ziemak, A., Hopej, M., Kamiński, R., & Martan, J. (2015). Simplicity as a feature of an organizational structure. Argumenta Oeconomica, 1(1), 259–276. https://doi.org/10.15611/aoe.2015.1.10

- Hough, L. M. (1984). Development and evaluation of the “accomplishment record” method of selecting and promoting professionals. Journal of Applied Psychology, 69(1), 135–146. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.69.1.135

- Kaptein, M. (2008). Developing and testing a measure for the ethical culture of organizations: The corporate ethical virtues model. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 29(7), 923–947. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.520

- Kuper, S., & Szymanski, S. (2017). Futbonomia. Dlaczego Anglia przegrywa, Hiszpania, Niemcy i Brazylia wygrywają i dlaczego USA, Japonia, Australia a nawet Irak staną się piłkarskimi potęgami [Soccernomics: Why England loses, Why Germany and Brazil Win, and Why the U.S., Japan, Australia …]. SQN Publisher.

- Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. (2002). Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation: A 35-year odyssey. American Psychologist, 57(9), 705–717. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.57.9.705

- Maeda, J. (2006). The laws of simplicity. The MIT Press.

- Maletič, M., Maletič, D., Dahlgaard, J. J., Dahlgaard-Park, S. M., & Gomišček, B. (2016). Effect of sustainability-oriented innovation practices on the overall organisational performance: an empirical examination. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 27(9–10), 1171–1190. https://doi.org/10.1080/14783363.2015.1064767

- Malik, F. (2019). Führen leisten leben: Wirksames management für eine neue welt. Campus Verlag GmbH.

- Matić, I. (2012). Measuring the effects of learning on business performances: Proposed performance measurement model. The Journal of American Academy of Business, 18(1), 278–284.

- Mell, J. N., Dechurch, L. A., Leenders, R. T. H. A. J., & Contractor, N. (2020). Identity asymmetries: an experimental investigation of social identity and information exchange in multiteam systems. Academy of Management Journal, 63(5), 1561–1590. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2018.0325

- Morawski, M. (2003). Problematyka zarządzania pracownikami wiedzy. Przegląd Organizacji, 1, 17–20.

- Mościcki, P. (2019). Lekcje futbolu [Football lessons]. W Podwórku.

- Ozbilgin, M., Tatli, A., & Jonsen, K. (2015). Global diversity management: An evidence-based approach (2nd ed.). Red Globe Press.

- Pirson, M., & Malhotra, D. (2011). Foundations of organizational trust: What matters to different stakeholders? Organization Science, 22(4), 1087–1104. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1100.0581

- Porck, J. P., Matta, F. K., Hollenbeck, J. R., Oh, J. K., Lanaj, K., & Lee, S. M. (2019). Social identification in multiteam systems: The role of depletion and task complexity. Academy of Management Journal, 62(4), 1137–1162. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2017.0466

- Pyöriä, P. (2005). The concept of knowledge work revisited. Journal of Knowledge Management, 9(3), 116–127. https://doi.org/10.1108/13673270510602818

- Schmidt, F. L., & Hunter, J. (1981). Employment testing: Old theories and new research findings. American Psychologist, 36(10), 1128–1137. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.36.10.1128

- Schnackenberg, A. K., & Tomlinson, E. C. (2016). Organizational Transparency: A New Perspective on Managing Trust in Organization-Stakeholder Relationships. Journal of Management, 42(7), 1784–1810. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314525202

- Schneid, M., Isidor, R., Li, C., & Kabst, R. (2015). The influence of cultural context on the relationship between gender diversity and team performance: a meta-analysis. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 26(6), 733–756. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2014.957712

- Senge, P. M. (2006). The fifth discipline: The Art & practice of The learning organization. Doubleday.

- Sparrow, P., Brewster, C., & Chung, C. (2017). Globalizing human resource management (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Sternberg, E. (2000). Just business: Business ethics in action. Oxford University Press.

- Stewart, J., & Harte, V. (2010). The implications of talent management for diversity training: An exploratory study. Journal of European Industrial Training, 34(6), 506–518. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090591011061194

- Trank, C. Q., Rynes, S. L., & Bretz, R. (2002). D.: Attracting applicants in the war for talent: Differences in work preferences among high achievers. Journal of Business and Psychology, 16(3), 331–345. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1012887605708

- Turner, J. C. (2010). Social categorization and the self-concept: A social cognitive theory of group behavior. In T. Postmes, & N. R. Branscombe (Eds.), Key readings in social psychology. Rediscovering Social Identity (pp. 243–272). Psychology Press.

- Tworek, K., Zgrzywa-Ziemak, A., Hopej, M., & Kamiński, R. (2020). Workforce diversity and organizational performance – a study of European football clubs. Argumenta Oeconomica, 2(45), 189–211. https://doi.org/10.15611/aoe.2020.2.08

- Vaiman, V., Scullion, H., & Collings, D. (2012). Talent management decision making. Management Decision, 50(5), 925–941. https://doi.org/10.1108/00251741211227663

- Vallance, S., Perkins, H. C., & Dixon, J. E. (2011). What is social sustainability? A clarification of concepts. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 42(3), 342–348. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2011.01.002

- Zgrzywa-Ziemak, A., & Walecka-Jankowska, K. (2021). The relationship between organizational learning and sustainable performance: an empirical examination. Journal of Workplace Learning, 33(3), 155–179. https://doi.org/10.1108/JWL-05-2020-0077

- Zgrzywa-Ziemak, A., Zimmer, J., & Hopej, M. (2022). The model of cohesive management capability-a theoretical framework. Scientific Papers Of Silesian University Of Technology. Organization And Management Series, 155, 609–622.

- Zhang, L. L., George, E., & Chattopadhyay, P. (2020). Not in my pay grade: The relational benefit of pay grade dissimilarity. Academy of Management Journal, 63(3), 779–801. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2016.1344