Abstract

“Aging in place” is a widely used term but its meaning and interpretation in literature and practice have often omitted older adults’ perspectives. This study sought to uncover the meaning of “aging in place” for older adults in Canada, the ways they think it can be supported, and the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on their perspectives. A survey probing these topics was distributed to older Canadians, and participants were invited to focus groups to elaborate. Approximately 70% of survey participants had heard of the term “aging in place” and 68% said that the pandemic had not changed their perspectives. Framework analysis of focus groups identified five themes related to aging in place: aging with choice, built environment, social environment, communication and information, and funding. This study highlights critical elements of aging in place in Canada and identifies gaps in choices available that can be addressed through nuanced research and policies.

Introduction

The world’s population is rapidly aging. The number of individuals aged 60 years or older has doubled since 1980 and is projected to reach 2 billion by 2050 (WHO, Citation2021). In Canada, by 2030, older adults will number over 9 million and make up 23 percent of the total population (Canada, 2014). As the population ages, global entities such as the World Health Organization (WHO), as well as nations across the world, have increasingly emphasized the need to innovate and adapt to provide appropriate and adequate support to older adults. A primary aspect of WHO’s “aging well” global priority is supporting the ability for people to age in place (WHO, Citation2014). In 2014, the Canadian government released the “Action for Seniors” report outlining six areas to better support Canada’s older adults, including a strategy focused largely on housing to help seniors age in place (Canada, 2014). The importance of this strategy was placed at the forefront at the onset of the Global COVID-19 Pandemic in 2020 when thousands of older Canadians, similar to many worldwide, were isolated from families and friends and many died in long-term care facilities (Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Citation2021; Tupper et al., Citation2020).

According to a national survey, more than 81% of older Canadians would prefer to age in their current place of residence, yet only 26% felt it would be possible to do so (March of Dimes Canada, Citation2021), which indicates a critical gap that must be better supported. Aging in place is associated with unique challenges due to the heterogeneity of older adults and varying resources at the community level, from very rural to cosmopolitan (Hartt & Biglieri, Citation2021). Recent research seeking to understand the relationship between spatial distribution and vulnerability of older adults has shown that rural communities in Canada are aging the most rapidly (Channer et al., Citation2020). Unfortunately, these smaller communities are the least likely to have begun preparing for this demographic shift through the implementation of age-friendly policies (Hartt & Biglieri, Citation2018). This diversity in the Canadian context of aging in place extends internationally to growing populations of older adults, and means that national approaches to supporting aging in place cannot be the only solution (Hartt & Biglieri, Citation2021).

As researchers and policymakers prioritize enabling “aging in place,” it is now important to clarify the meaning of this term and its expected or intended outcomes that surround the choices older adults are making. “Aging in place” has been in use since the late 1980s, with the term having variable meanings, from (Bigonnesse & Chaudhury, Citation2020) staying in the same home to aging in any setting of one’s choice (Bigonnesse & Chaudhury, Citation2020; Forsyth & Molinsky, Citation2021; Weil & Smith, Citation2016). Unfortunately, the perspective of older adults themselves is rarely included in formulating the definition (Bigonnesse & Chaudhury, Citation2020), and definitions may not account for the ways in which places change over time, and an individual’s attachment, choices the person makes, or the desire to stay in a place may also change (Lewis & Buffel, Citation2020). Moreover, aging in place is not a universal solution or even a positive experience for many older adults, especially for marginalized groups (Byrnes et al., Citation2006; Weil & Smith, Citation2016). Thus, defining what it means to age in place requires consideration of aging adults’ perspectives.

There is a need to understand what it means to have a place to call “home” and how this might change over time. Beyond just a space to eat, sleep, and be sheltered, a home is where an individual can attain a sense of safety, security, and belonging. It serves as a hub to social supports that connect individuals to larger communities so that one may engage meaningfully in the place where they live. A home is connected to a network of individuals (e.g., family, friends), infrastructure, and amenities that satisfy one’s wants and needs (Mallett, Citation2004; Oswald & Wahl, Citation2005). Many physical and physiological transitions are experienced by an individual as they age, and their home ought to accommodate changes in needs and values accordingly. People may change the location they call “home” by choice or by circumstances beyond their control. Thus, the dynamic complexity of the “place” in aging in place necessitates a nuanced approach that requires (a) the inclusion of older adults in the process of defining what aging in place means, and (b) incorporation of this knowledge so that policies and recommendations are relevant to older adults’ experiences, choices, and needs.

The purpose of this study was to gain a perspective from older adults on their view of what aging in place means, inclusive of their information and communication needs, as well as their needs and perspectives on physical, emotional, social, and cognitive supports.

Methods

Participants

Following ethics approval from University of X-Named Board [H21-01778], participants were recruited from our partner organization, the National Association of Federal Retirees (NAFR). This organization of nearly 170,000 retired members of the federal public service (60% males; 51% aged 70 years and older) sent e-mail invitations to participate to all provincial chapters and assisted in nationwide recruitment through in-print advertisements in the organization’s Sage Magazine.

Volunteers were invited to participate in a short (∼10 minutes) online (Qualtrics) survey in October 2021. Informed consent was gathered at the beginning of the survey. At the end of the survey participants were asked to sign up for an optional follow-up online focus group (via Zoom) where participants could expand on and discuss their survey responses with the researchers. Verbal consent was confirmed at the beginning of each focus group. Inclusion criteria were aged 60 years and older, with access to a computer or mobile device with an Internet connection, able to receive online surveys through e-mail and read and write in English or French for the survey, and able to communicate orally in English to participate in focus groups. In total, 489 older adults responded to the online survey and 19 of these participated in focus groups. Demographic characteristics of survey respondents are reported in .

Table 1. Survey demographic data. Not all participants answered each question; percentages and number of responses (N) for each question are provided.

Data collection

The online survey asked questions about older adults’ understanding and preferences for aging in place and receiving science and health-related information, along with basic demographic data to contextualize their responses. A week after the survey closed, four 40- to 60-minute online focus groups were hosted via Zoom. Immediately preceding the focus groups, the research team provided a brief presentation on the survey. Participants were then randomly assigned to a focus group of four to six participants with one or two facilitators and a scribe. Focus groups were recorded and transcribed. Transcripts were cross-checked with recordings by a researcher (MF) to ensure accuracy. The focus group centered around three topic areas: (a) the meaning of aging in place and how autonomy fits, (b) preferred housing and why, and (c) supports for aging in place and their importance.

Survey analysis

Survey responses to demographics, multiple-choice, and ranking questions were summarized using descriptive statistics. Inductive content analysis (Erlingsson & Brysiewicz, Citation2017) was used (by MF) to analyze the two open-ended survey questions of “Regardless of whether you are familiar with the term [aging in place], what do you perceive “aging in place” to mean?” (N = 480 responses) and “Aging in place can have many different meanings, and how people find and use resources varies widely. What didn’t we ask that you would like us to know?” (N = 278 responses). The latter question provided additional context to the issues of aging in place that participants felt were important. Codes were developed (by MF, JJ) by reviewing a subset of the responses and an initial codebook was developed. All responses were then assigned codes and grouped into themes. The frequencies with which themes appeared were tallied and presented as percentages of overall responses. Many responses included more than one theme.

Focus-groups analysis

Data analysis was guided by deductive framework analysis, where data were sifted, charted, and sorted in accordance with key issues and themes using five steps: (a) familiarize; (b) identify a thematic framework; (c) index; (d) chart; and (e) map and interpret (Gale et al., Citation2013; Ritchie & Spencer, Citation2002). To familiarize the researchers with the focus groups, two study-team members (MF, TF) read through all of the focus group field notes and a few transcripts. Through team meetings (with MF, TF, JJ) a preliminary thematic framework was identified based on key issues and commonalities emerging from the surveys and focus groups. Using Nvivo 12 software, team members (MF, TF) coded one of the focus-group transcripts based on the thematic framework, with discussion among team members, as new codes and subthemes were identified and indexed. Full paragraphs were coded so that contextual meaning was not lost. The focus-groups codebook guided the interpretive, analytical process to understand what main factors participants deemed essential for aging in place. Data were then summarized by charting illustrative quotes that best exemplified the themes. As part of the interpretive process, team meetings were held to discuss the data and map and interpret the common themes and subthemes.

Results

The majority of survey participants lived in British Columbia (97%), in a single-family home (65%) and felt supported (82%) to maintain their independence as they age. Most respondents said they would prefer to age in a single-family home (60%) or a condo/apartment (28%), and 68% of respondents said that their experience with the COVID-19 pandemic had not changed their perspective on aging in place. Participants ranked family support and social support as the most important factors to maintaining independence (). Built environment was ranked similarly to social supports as the most important factor; however, nearly twice as many respondents ranked built environment (∼13%) relative to social support (∼7%) as the lowest factor toward maintaining independence. Ninety-two percent of participants felt that accurate information on science and health-related topics is accessible to them. Sources of such information were ranked according to importance, and health practitioners (∼32%) were recognized as the most important source, and friends and family (∼5%) and social media (∼2%) as the least important ().

Table 2. Survey question: rank importance of factors to remain independent.

Table 3. Survey question: rank importance of sources used to gain up-to-date information on science and/or health-related topics.

What does aging in place mean to you?

Seventy percent of participants had heard of the term “aging in place” (344 of 488). Of 480 responses to the open-ended question “What do you perceive Aging in Place to mean?,” 417 (87%) described remaining in one’s own home or community as one grows older. Of these answers, 30% also included a description of services and supports for medical or everyday needs in the home and/or community (127 of 417). Descriptions emphasizing independence and choice were a less common theme, appearing in 8% of total responses.

The content analysis of the 278 responses to the final survey question—“What didn’t we ask that you would like us to know?”—resulted in four primary themes: funding, built environment, healthcare, and communication and information. Two additional themes appeared: social environment and aging with choice, which was subsequently broached in the focus groups. There was significant overlap between themes, and many responses included more than one theme, so the percentages indicating the total number of responses that mentioned that theme do not add up to 100%.

Funding and financial planning were major concerns and were mentioned in 23% of responses. Disapproval of how the government supports older adults to age in place was highlighted as a key concern. Many participants had financial concerns related to the feasibility of aging in place and did not feel adequately supported by the government.

The built environment was evident in 23% of responses and included discussions of infrastructure and the need for services to help with daily activities, such as housekeeping, cooking, and so on. Many participants described their increasing need for assistance with these daily activities and other nonmedical in-home services.

Healthcare comprised 21% of responses in two categories: systemic healthcare issues and personal health concerns. Participants described the current healthcare system and its inability to support the aging population: Doctor shortages, wait times, and a lack of in-home medical care were noted as ongoing issues. Personal health concerns related to aging, including mental health, were mentioned as influencing one’s ability to age in place.

Access to reliable communication and information on the availability of services and supports needed to age in place was identified by 16% of respondents and seen as imperative to supporting older adults to age in place. Many also discussed technological barriers to access.

Additional themes identified from this survey question were the social environment (13% of responses) and aging with choice (11% of responses). All themes are integrated and described in detail in the focus group results given next.

Focus groups

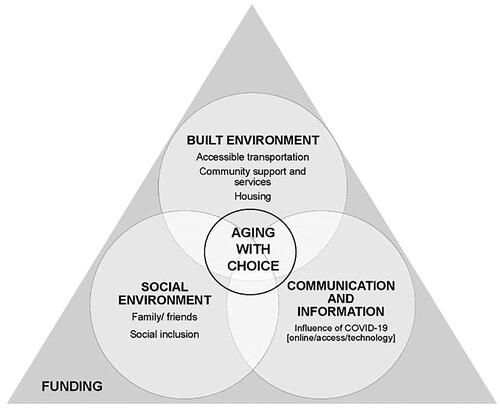

Five men and 14 women participated in the focus groups. Fifteen of them were from various regions of British Columbia, one was from Alberta, one was from Manitoba, and two did not share where they lived. The focus-groups codebook guided the interpretive, analytical process that resulted in five central themes emerging: aging with choice, built environment, social environment, communication and information, and funding ().

Figure 1. Aging with choice is embedded and interlinked across all themes and subthemes. This is represented by the inner circle. The built environment, social environment, and communication and information are overlapping factors that arose in focus groups. The funding landscape influences and provides context for all other themes in some way.

Aging with choice

The overarching position of literature (Bigonnesse & Chaudhury, Citation2020; Forsyth & Molinsky, Citation2021; Lewis & Buffel, Citation2020; Weil & Smith, Citation2016) is, aging in place is remaining in the same home. Various methodologies have been applied to a push–pull framework (Franco et al., Citation2021) to understand housing decisions of older adults (Roy et al., Citation2018), yet the opinion and voice of older adults on the matter of where they want to live are often overlooked. Messaging around aging in place in this study from older people is they wanted to have choices about their living arrangements. In order to have choices, participants recognized the need to be able to engage with the decision-making process.

Decision-making process

When asked what aging in place means to the participants, they predominantly focused on the need for anticipation and planning early and throughout the aging process to ensure decisions were made from a place of “choice” versus “necessity.” Participants spoke about the importance of having the opportunity to make their own decisions [having a sense of agency] and taking responsibility for their future selves.

Paul: Yeah, there’s also an element about taking responsibility for yourself, and knowing when it’s time for you to move.

Judy: I think it’s incumbent on people to think ahead a little bit and say, Well, I love my community. But how feasible is it without family members who can take me to appointments? I mean, we’d all like to stay in our own home, but, that doesn’t happen, most people need to go into a hospital or have to go into institutional care, because of different circumstances.

To live where you choose

To participants, “aging in place” meant living where one chooses, and for many this meant staying in their own homes and communities. Participants spoke about the need to be aware of how their physiological and social needs may transition as they age and discussed the types of supports, they may require to adapt their environment(s). Having access to viable transportation, housing alterations, community support, and various services was essential to support late-life transitions. If supports were not available then their needs and ability to live in their own home and communities would not be satisfied and they would likely have to move for necessity rather than by choice.

Mary: Aging in place means to me having the support we need at, at our fingertips.

Eileen: I think it’s very important that you make the decision before you’re not able to make the decision, that you don’t have a choice anymore because of your physical limitations. So maybe by making that decision, you can work with the services that are available to help move you from one level to another.

Built environment

The term “built environment” (or “urban form”) of the city or neighborhood refers to aspects of our surroundings that are built by humans, that is, distinguished from the natural environment. It includes buildings and structures (e.g., scale, design), land use patterns (e.g., functions, amenities and services), outdoor spaces and elements (e.g., parks, benches, lighting), and infrastructure that supports human activity, such as transportation networks (e.g., roads, sidewalks, and transportation services) (Chaudhury et al., Citation2016; Chudyk et al., Citation2017).

Accessible transportation

Participants noted the importance of having access to various modes of transportation. The majority of participants had access to a vehicle that they or someone they knew drove; many were not aware of alternative options. Those that did speak of alternative options often highlighted the dismal availability and accessibility. These individuals often lived outside of the city, where fewer options were available than in more urban areas.

Ruth: But the big thing is transportation. There are lots of lovely condos in our area. And it’s great as long as you can drive. But if you lose the ability to drive, then you have to really pay attention to how close the bus stop is or whether or not you can afford taxis or whether or not you have friends who can drive you.

Frances: I understand transportation is a big issue for people, particularly people who live in semirural areas, we find that there’s very little options other than to drive themselves.

Community support and services

Access to and availability of community supports and services were influenced by the built environment. Older adults who lived in communities with a greater availability of community supports and services felt better suited to age in place.

Paul: The place I chose is actually within a block of a major mall. And there’s all kinds of services there if I need them.

Judy: When you start to think about aging in place, we have to be realistic, I, I’m surprised by the number of my friends in my same age group, early 60s, that they’ve chosen to retire from the big city, the busy city and gone to smaller communities on [name of place], which I don’t understand. For myself, we’ve, we’re not going to do that. I mean, when you go to a smaller place, [sic] then the services are, are not there.

However, many older adults noted that not everyone wants to live in a city, and some older people desire to live in more remote locations, although services may not be available—thus the tug-of-war between access to services and preferred location.

Frances: I think for people who are reaching their golden years, they’re finding out they’re not quite as golden as they had anticipated. And I believe that we need to establish better access to services. For most age groups, once you start to have chronic illness enter your life, you need support, both socially and medically, as well as housing … My concern is the supports haven’t been there for people to do that. And I’m not sure that they’ll be there in the future.

Housing

Many recognized the need for alternative housing options and/or adapting their current homes to make them more age-friendly. Fear of falling and the inability to conquer stairs were seen as a prime driver of wanting to move from a multistory house to a single-floor condo/apartment.

Ruth: We currently live in a three-story house. And I see myself down the road. Moving to perhaps a condo.

Managing activities of daily living (ADLs) was also noted by many as influencing their choices when it came to housing options. Older adults felt the need to plan whether or not their current housing situation supported access to services that could assist them with ADLs.

William: Who are these people that are going to come in and help like, are there going to be these people around? When it comes to our turn for perhaps needing these people to come in to either, you know, help with meals or help with cleaning the place? Or even if if you’re ill, but not ill enough to be in hospital? To, you know, come in and make sure you’re taking your medication? And who who’s gonna do that?

Social environment

The social environment encompasses “the immediate physical surroundings, social relationships, and cultural milieus where groups of people function and interact” (Barnett & Casper, Citation2001).

Both the built environment and the unbuilt can be considered as a complex dynamic system. Conceptually, and recently, a more inclusive model involving social capital supports has evolved within the built environment, in part owing to environmental impacts and resource scarcity (Moffatt & Kohler, Citation2008; Mazumdar et al., Citation2018).

Family and friends

For many participants, family and friends were repeatedly mentioned as invaluable to the aging in place experience. Aging in place was about living in environments not only where they have access to community services but also where they have access to their social network. Often access to community services, such as community centers, interchanged with access to social connections, providing a sense of community/social belonging.

Brenda: That’s our wish to be able to stay here as long as possible. I do have a disability but my house is handicapped equipped. I prefer to stay in an area where all my friends/contacts are etc. [sic] I would hate to be stuck in another area where we don’t have our friends and we don’t have all the medical staff we’re comfortable with.

Many older adults, however, no longer lived near their family, or their preference was not to “burden” their family with the responsibility of caring for them. Therefore, community services to supplement their needs were seen as critical.

Pam: I was determined that wouldn’t put my kids through making decisions for me. I guess, I guess that’s the autonomous part.

Social inclusion

Apart from family and friends, social elements that emerged from the aging-in-place discussion included ensuring one felt a sense of inclusion within one’s greater community to stave off isolation and loneliness. The notion of intergenerational communities arose as a potential solution to combat foreseeable isolation.

Sylvia: I think isolation is probably our biggest problem for just about all seniors, and the fact that we’re treated like we’re invisible. So maybe more community interaction of some sort. With seniors and younger people that maybe don’t have seniors in their lives.

Communication and information

Communication influences knowledge, and although innovations in health information technology are enabling advances in health resources, the well-documented age-based digital divide can also result in hasty or short-sighted decision making for older adults (Hall et al., Citation2015; Zhao et al., Citation2023). What remains unknown is the avenue and resources in which older adults prefer to receive their information to make informed decisions.

Focus-group participants felt that one major obstacle to aging in place and maintaining independence was inability to access information about the availability of services and resources.

Nancy: A perfect example of that, where that particular lady, there was things for her but she wasn’t aware of them. I had to do the digging to find it for her. So in some cases it’s it’s [sic] there but you have no idea it’s there.

The positives and negatives of the influence of COVID-19 were discussed in terms of access to information and community services. For example, since the beginning of the pandemic, participants spoke about social isolation as well as increased access to community services, such as ordering groceries online for delivery to the home. These “new” services were perceived as a positive outcome and people would like the services to be continued in the future.

Barb: I think the pandemic has really limited social interaction, and contributed to social isolation for seniors.

Sylvia: One thing that is positive from the pandemic is that just about every grocery store in town now delivers. And if your community doesn’t have grocery stores to deliver get people together and and request, it might be as simple as that when they realize there is quite a demand for that kind of service.

On the other hand, the already heavy reliance on the Internet to access services only increased during the pandemic, which left many older adults feeling “left out” now that they had to be Internet-savvy to access what previously used to be in-person services.

Linda: There’s also the issue of the Internet, for example, my doctor when she set up in this little place, you have to book your appointments online. We were offered, we were asked to sign up to register, by the first of September, and you had to do that online. You have to make your appointments online. Or even to go to the post office now, if you want to mail something overseas. You’re being asked to complete your customs form online, before you get there.

Funding

Integrating health and social care for community-dwelling older adults is a well-known need to meet the needs of older adults. In Canada, strategies are primarily documented in Ontario (Johnson et al., Citation2018), and coupled to the sparsity of data from other provinces is the accompanying perspective of older adults on funding for aging in place.

There was a clear stance from the participants on wanting the government to focus their efforts on home support rather than on long-term care. The older adults who participated in this study wanted to stay in place and they wanted options (e.g., community supports, housing alternatives) accessible to them to do so. Participants emphasized a shift in political focus and budgets to meet the needs of our aging Canadian population.

Tom: I’d like to see our health system [be] more proactive than reactive to get better care and a better future for myself and my wife.

Mary: Our government system is placing the resources in facilities, and not so much to into home support. I really think that we’re at a tipping point here, I think our generation really don’t want to use the facilities that our parents went to. But we’re really looking for other options. And I think it’s time we really broke out of that mold of constantly building great big facilities, which tend to be private.

Many older adults spoke about the COVID-19 global pandemic and how it brought to light what many have known for a very long time, that the current situation of placing older adults in long-term care/nursing homes is not sustainable, nor desired by older adults.

Discussion

By giving credence and primacy to older adults’ voices, our findings provide insight into Canadian older adults’ perspective of aging in place. This study revealed five interrelated themes that older adults in Canada are considering when it comes to aging in place: aging with choice, the built environment, the social environment, communication and information, and funding. The lived experiences of COVID-19 did not alter perspectives of aging in place; rather, they reinforced attitudes toward community and living independently, as well as the need for efficiency in accessing accurate and reliable information. “Aging with choice” was woven into all aspects of aging in place, and participants were highly aware of the importance of planning ahead to ensure decisions were made from a place of “choice” versus “necessity.” Staying at home or within the same community was important to participants, but most recognized that wants and needs change across the life span and that having acceptable choices available is key—including affordable and accessible services. Similarly, concerns about financial feasibility, lack of government support, and healthcare costs all affect the choices a person may have to make.

What does it mean to age in place?

Definitions of aging in place vary and fall into three categories: place-based, service-based, or choice-based (Forsyth & Molinsky, Citation2021). This aligns with our Canadian survey responses to the question “What does aging in place mean to you?” While survey responses to this question focused heavily on place and services, when prompted further in both the survey and the focus groups we found that, similar to results of other studies (Choi, Citation2022; Wiles et al., Citation2012), choice was intertwined with all aspects of aging in place. To age in place means having choice: choice when it comes to decision making and choice in where one lives. To age in place, in effect, is talking about a set of deeply felt values. For some this may mean a desire to stay in one’s familiar neighborhood, close to friends and amenities that hold meaning. For others, to age in place is not necessarily associated with where they have lived most their life, but a place where they choose to live. Overall, older adults identify with external factors and supports that they require to age in place, with the predominant internal factor being choice: autonomy in decision making. To achieve this, there need to be system supports that are external to the individual, and this is inclusive of communication and information. It is essential to bring awareness on the benefits of bettering individual health toward self-empowering the choices that are external and live within “systems” that older adults recognize as factors for aging in place.

Eighty-two percent of survey participants stated that they felt supported to maintain their independence as they age. However, in the open-ended survey questions and focus groups, we discovered many older adults have concerns about the future of aging in place both individually and at a societal level. Participants spoke about the need for transportation, housing, services, outdoor spaces, social supports, and funding to accommodate aging in place, which aligns with a pre-COVID-19 report of older adults in rural Canada (Bacsu et al., Citation2014). Unique to our work is that participants acknowledged the critical need for early anticipation and planning in order to maintain a sense of choice within each of these factors (e.g., transportation, housing etc.) as they age. Proactive decision making was seen as a form of preventative planning in order to avoid being moved to a place deemed less desirable and not of choice (e.g., nursing home, long-term care).

There was very little discussion of internal factors that center on the individual’s maintenance of physical and cognitive health or personal approaches to preventing age-related decline. These elements ranked as less important relative to external factors such as accessible housing, transportation, technology, and access to healthcare. Participants focused largely on planning for external elements to support aging in place (e.g., the built and social environments) and seemed to view health-related decline as unpredictable or inevitable. Many older adults view age-related decline to be outside of their control (Sarkisian et al., Citation2002) and therefore may be more interested in preparation for those elements of aging in place that they feel are within their control. Research shows that engaging in healthy behaviors continues to benefit individuals as they age and that positive attitudes about aging can increase these behaviors (Levy & Myers, Citation2004) and overall health outcomes (Nakamura et al., Citation2022). While there is abundant evidence for this phenomenon, our study indicates that older adults may not consider personal health behaviors as key components of aging in place, a critical knowledge gap and one that can and likely should be addressed through science translation activities.

How a place should accommodate the aging process

The age-friendly cities framework developed by the WHO offers a helpful structure by which to interpret the results of the surveys and focus groups. While this framework did not inform our initial approach to the survey and focus groups, there is significant overlap in the themes that arose in this study and the eight domains identified by the WHO: outdoor spaces and buildings, transportation, housing, social participation, respect and social inclusion, civic participation and employment, communication and information, and community support and health services (WHO, Citation2007). Fifteen years later, the age-friendly cities framework continues to have relevance toward helping cities and communities to adapt to aging populations. However, despite all 10 provinces in Canada having launched some sort of age-friendly cities and communities initiative, their implementation and evaluation remain a challenge (Menec & Brown, Citation2022).

Older adults are not a homogeneous group, and some participants spoke about wanting to live in rural/remote locations, but poor access to transportation, amenities, and services made this choice difficult. Other participants opted to live in cities to be close to amenities, but relied heavily upon personal vehicles as their mode of transportation. Few considered how they would navigate transportation if they lost access to their vehicles. Canadian research has shown that although cities and smaller communities are using the age-friendly concept to engage with older adults to identify local needs and priorities, little progress is being made to upgrade the quality of the built environment (including transportation networks), which obviously affects the ability to age in place (Miller, Citation2011).

Access to quality transportation has been linked to better health outcomes for older adults by improving not only their physical but also social health needs (Webber et al., Citation2010). Age-friendly strategies must focus on different spatial scales, from large cities to small remote/rural communities, and understand the varying transport, support services (e.g., amenities), and housing needs at these different spatial scales to meet older adults’ needs where they choose to live (city/rural/remote) (van Hoof et al., Citation2021).

Housing plays a key role in creating age-friendly environments and influencing health, independence, well-being, and the ability to age in place (WHO, Citation2007). Various models of housing for older adults, such as cohousing, naturally occurring retirement communities that include supportive service programs, and villages, have been shown to have their advantages and disadvantages (Mahmood et al., Citation2022). All these models constitute three key interrelated, age-friendly components that arose in this study: (a) physical accessibility within the home and in the community, (b) services and supports, and (c) social participation and engagement (Menec et al., Citation2011).

How we build our neighborhoods, communities, and cities affects our ability to support older adults to age in place. Of particular importance, and valued by older adults themselves, is building spaces to encourage social interaction rather than breed feelings of displacement and isolation. For example, walkable neighborhoods support independence and mobility while providing access to social networks and meaningful involvement within community networks (Turcotte, Citation2015; van den Berg et al., Citation2016). Lack of access to sidewalks or even street furniture (benches) discourages older adults to get out, be active, and socialize in their communities (Ottoni et al., Citation2016). Livable environments that support aging in place are articulated through a strong sense of place, defined as the social, psychological, and emotional bonds that people form with their environment (Wiles et al., Citation2012).

The importance of the social environment

The social environment plays an important role in aging in place. Older adults rely on layers of community, ranging from family, to friends, to community involvement and volunteerism. Each of these components of the social environment plays a different role in the lives of older adults. Although family supports were ranked as most important in remaining independent, a significant proportion of participants ranked family support as the least important factor in maintaining independence (17%, ). The qualitative data showed that some participants were averse to receiving help from or placing a burden on family, indicating that family support has a highly personal and complicated role in aging in place. How funding systems can support aspects of family assistance is complex and requires specific study, which likely involves understanding autonomy of the aging adult within the complexity of various family models. Further study is required.

Participants spoke about their desire for intergenerational communities. Not surprisingly, research shows that aspects of the social environment, such as diversity of social contacts, high levels of social participation, large social network size, presence of living children, ethnic homogeneity of an area, and high levels of perceived neighborliness, are associated with improved health and reduced rates of mortality (Annear et al., Citation2014).

Access to information—What future role does technology play?

Nearly all survey participants felt they had access to accurate information on science and health-related topics (92%). Participants identified health practitioners as their most important source of science and health-related topics. However, the COVID-19 pandemic negatively impacted access to health practitioners. Qualitative data revealed that for many, access to information is at the heart of their decision-making process to age in place and older adults want more efficient and equitable ways to access it.

On a global scale, an overhauled model of age-friendly cities is needed. The digitalization of our societies has not been properly included in existing models, including the age-friendly cities guidelines. Not including technology in the age-friendly cities guidelines is a missed opportunity for understanding what impact digital exclusion can have on individuals and communities, especially when services are integrating digital formats as their primary engagement option (van Hoof et al., Citation2021). For example, participants noted the advantages that emerged from COVID-19 in terms of technology in relation to service delivery, but also mentioned the disadvantages of reliance on access to technology. Many mentioned they were less comfortable with technology and preferred in-person services. This phenomenon has been called the “double burden of exclusion” (Seifert et al., Citation2021). Older adults who may not be online are subjected to digital exclusion when services rely on access to the Internet, such as for taxi or car services. While older adults are often positioned as “not wanting to engage in newer technology” (Lopez et al., Citation2021), this notion could be shifting. Trends indicate that healthy older adults are increasing their Internet use, though the same trend was not observed for those with functional limitations and multiple comorbidities or the oldest-old (Schulz et al., Citation2015). Future work should look into how technology is becoming an increasingly important domain related to aging and independence, and include older adults in the design of future technologies and research studies aimed at supporting technology needs and knowledge for them to age in place.

Who will fund aging in place?

The median household income for older adults in Canada is the lowest of any age cohort over the age of 25 years (Statistics Canada, Citation2016). In Canada, single people older than 65 years have a median income of $30,400 (Statistics Canada, Citation2016), meaning half of single Canadian older adults are living on less than $30,400 a year. For older Canadians paying property tax or rent, insurance, and private care, on top of daily expenses—independence as they know it is unsustainable. Older adults with lower incomes may have less access to transportation or may travel less for activities such as shopping or socializing (Peel et al., Citation2005). Aging in place requires policy solutions that facilitate older adult choices, to support the process of aging with choices available. Approaches to policy recommendations require multiple studies to understand the diversity of choices older adults are making, and want to make, to age in place. Such solutions to support aging in place at the individual level might include options for in-home cleaning, yardwork, errands, and supports for greater needs such as in-home nursing aids for self-care. Funding of better public transportation networks to underserviced areas, inclusive of those outside city centers, may also assist older adults to live independently longer in familiar communities. This further facilitates gaining assistance from their established network, and enables continued contribution to their familiar community.

It took a pandemic to expose the long-standing systemic deficiencies that impact our aging population in long-term care (Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Citation2021). These shortcomings have largely been overlooked by the general population and ignored by governments, until now. Our findings suggest that COVID-19 did not change older adults’ perspectives on aging in place; if anything, it reinforced their choice to age in place, in their own homes and communities. Governments must pay attention: Older adults want to age in place, and critically, to do so they need choices. Choices need to be available through ongoing evolution of policies that support in-home living with assistance through established and evolving funding sources. It is time to shift the dial from investment in long-term care to investment in home care, support services, and preemptive planning so that older adults can have more choices regarding their present situation and better prepare for their future.

Limitations

Given the partnership with the NAFR, our sample was representative of their portfolio of members. Surveys were distributed via NAFR e-mail communication to British Columbia chapters, whereas other parts of Canada only read about the survey via the printed Sage Magazine, which required a response via e-mail to participate. This distribution strategy significantly impacted the survey responses, with the vast majority (97%) being British Columbia residents. The majority of participants were white, married, and almost all had completed secondary high school, a bachelor’s degree, or a postgraduate degree. As such, their level of formal education may not be representative of other older adult groups throughout Canada.

We know that the meaning of and the ability to age in place are impacted by socioeconomic status (Byrnes et al., Citation2006) as well as cultural differences (Hwang, Citation2008), and therefore the present study, notably with a small focus-group size, does not capture all of the diverse Canadian perspectives on this topic. Marginalized persons, such as the voices of immigrants and Indigenous people, are lacking in this dataset. To ensure that the diversity of older adults is represented, dedicated and meaningful partnerships need to be formulated to develop relevant research approaches to fully inform the perspectives of all people in Canada to age in place. Herein, with more research, the model of aging in place can evolve to an inclusive representation to support equitable choices for older adults aging in place. Our findings align well with previous studies investigating the perspectives of older adults on the meaning of aging in place (Bacsu et al., Citation2014; Wiles et al., Citation2012) and, importantly, the novel aspect of agency, and emphasis on choice.

Conclusions and future directions

Our findings provide insight into how Canadian older adults view aging in place and their preferences and needs with respect to aging in place. While there is no one size fits all solution, our research findings are consistent with Canadian surveys (March of Dimes Canada, Citation2021) and demonstrate that older adults want to age in place, in their own homes and communities. The lived experiences of COVID-19 did not alter perspectives of aging in place; rather, they reinforced attitudes toward community and living independently, as well as the need for efficiency in accessing accurate and reliable information.

Optimal choices become possible only when the built environment and the social environment are supportive of aging in place and when information on how to access those supports is readily available. All of the themes identified in this study are influenced by the underlying funding landscape. Researchers and policymakers seeking to support aging in place must be aware of this complexity and build it into their studies, recommendations, and programs. By taking a participant-centered approach, the future of aging in place research can hone in on specific issues while accounting for the intertwined nature of all of these aspects of aging in place and for individual, family, cultural, geographical, and other intersectional variations. Further research focusing on Canadian populations not well represented in this study is needed to understand how this variation influences the meaning of aging in place and the types of support most needed for all older adults.

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Association of Federal Retirees of Central Okanagan for its support in this project, inclusive of activities to support the research as well as engagement with the national office. We also thank Thea Franke (PhD), who consulted and assisted with focus-group coding and analysis, and Phuonglisa Ha (Lisa) and Paige Copeland, who attended the focus groups to take notes and assist with the Zoom room, and Dr. Jill Williamson for communication and organizational support post data collection. The research was supported by the Vice President Research UBC Okanagan award for Research Clusters. Christiane Hoppmann gratefully acknowledges support from the Canada Research Chairs Program. Brodie Sakakibara gratefully acknowledges support from the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, JMJ, upon reasonable request.

References

- Annear, M., Keeling, S., Wilkinson, T., Cushman, G., Gidlow, B., & Hopkins, H. (2014). Environmental influences on healthy and active ageing: A systematic review. Ageing and Society, 34(4), 590–622. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X1200116X

- Bacsu, J., Jeffery, B., Abonyi, S., Johnson, S., Novik, N., Martz, D., & Oosman, S. (2014). Healthy aging in place: Perceptions of rural older adults. Educational Gerontology, 40(5), 327–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/03601277.2013.802191

- Barnett, E., & Casper, M. (2001). A definition of “social environment”. American Journal of Public Health, 91(3), 465. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.91.3.465a

- Bigonnesse, C., & Chaudhury, H. (2020). The landscape of “aging in place” in gerontology literature: Emergence, theoretical perspectives, and influencing factors. Journal of Aging and Environment, 34(3), 233–251. https://doi.org/10.1080/02763893.2019.1638875

- Byrnes, M., Lichtenberg, P. A., & Lysack, C. (2006). Environmental press, aging in place, and residential satisfaction of urban older adults. Journal of Applied Sociology, os-23(2), 50–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/19367244062300204

- Canada, E. and S. D. (2014). Government of Canada—Action for Seniors report [Research]. https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/programs/seniors-action-report.html.

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research. (2021). COVID-19’s impact on long-term care. https://www.cihi.ca/en/covid-19-resources/impact-of-covid-19-on-canadas-health-care-systems/long-term-care.

- Channer, N. S., Hartt, M., & Biglieri, S. (2020). Aging-in-place and the spatial distribution of older adult vulnerability in Canada. Applied Geography, 125, 102357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2020.102357

- Chaudhury, H., Campo, M., Michael, Y., & Mahmood, A. (2016). Neighbourhood environment and physical activity in older adults. Social Science & Medicine, 149, 104–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.12.011

- Choi, Y. J. (2022). Understanding aging in place: Home and community features, perceived age-friendliness of community, and intention toward aging in place. The Gerontologist, 62(1), 46–55. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnab070

- Chudyk, A. M., McKay, H. A., Winters, M., Sims-Gould, J., & Ashe, M. C. (2017). Neighborhood walkability, physical activity, and walking for transportation: A cross-sectional study of older adults living on low income. BMC Geriatrics, 17(1), 82. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-017-0469-5

- Erlingsson, C., & Brysiewicz, P. (2017). A hands-on guide to doing content analysis. African Journal of Emergency Medicine: Revue africaine de la medecine d'urgence, 7(3), 93–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.afjem.2017.08.001

- Forsyth, A., & Molinsky, J. (2021). What is aging in place? Confusions and contradictions. Housing Policy Debate, 31(2), 181–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2020.1793795

- Franco, B. B., Randle, J., Crutchlow, L., Heng, J., Afzal, A., Heckman, G. A., & Boscart, V. (2021). Push and pull factors surrounding older adults’ relocation to supportive housing: A scoping review. Canadian Journal on Aging = La revue canadienne du vieillissement, 40(2), 263–281. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0714980820000045

- Gale, N. K., Heath, G., Cameron, E., Rashid, S., & Redwood, S. (2013). Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 13(1), 117. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-13-117

- Hall, A. K., Bernhardt, J. M., Dodd, V., & Vollrath, M. W. (2015). The digital health divide: Evaluating online health information access and use among older adults. Health Education & Behavior, 42(2), 202–209. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198114547815

- Hartt, M., & Biglieri, S. (2021). Introduction. In M. Hartt & S. Biglieri (Eds.), Aging people, aging places: Experiences, opportunities, and challenges of growing older in Canada (pp. 1–11). Policy Press.

- Hartt, M. D., & Biglieri, S. (2018). Prepared for the silver tsunami? An examination of municipal old-age dependency and age-friendly policy in Ontario, Canada. Journal of Urban Affairs, 40(5), 625–638. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352166.2017.1360744

- Hwang, E. (2008). Exploring aging-in-place among Chinese and Korean seniors in British Columbia, Canada. Ageing international, 32, 205–218.

- Johnson, S., Bacsu, J., Abeykoon, H., McIntosh, T., Jeffery, B., & Novik, N. (2018). No place like home: A systematic review of home care for older adults in Canada. Canadian Journal on Aging = La revue canadienne du vieillissement, 37(4), 400–419. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0714980818000375

- Levy, B. R., & Myers, L. M. (2004). Preventive health behaviors influenced by self-perceptions of aging. Preventive Medicine, 39(3), 625–629. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.02.029

- Lewis, C., & Buffel, T. (2020). Aging in place and the places of aging: A longitudinal study. Journal of Aging Studies, 54, 100870. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaging.2020.100870

- Lopez, K. J., Tong, C., Whate, A., & Boger, J. (2021). “It’s a whole new way of doing things”: The digital divide and leisure as resistance in a time of physical distance. World Leisure Journal, 63(3), 281–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/16078055.2021.1973553

- Mahmood, A., Seetharaman, K., Jenkins, H.-T., & Chaudhury, H. (2022). Contextualizing innovative housing models and services within the age-friendly communities framework. The Gerontologist, 62(1), 66–74. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnab115

- Mallett, S. (2004). Understanding home: A critical review of the literature. The Sociological Review, 52(1), 62–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954X.2004.00442.x

- March of Dimes Canada. (2021, April 27). Transforming lives through home modification: A march of dimes canada national survey. https://www.marchofdimes.ca/en-ca/aboutus/newsroom/pr/Pages/MODC-Home-Modification-Survey.aspx.

- Menec, V., & Brown, C. (2022). Facilitators and barriers to becoming age-friendly: A review. Journal of Aging & Social Policy, 34(2), 175–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/08959420.2018.1528116

- Menec, V. H., Means, R., Keating, N., Parkhurst, G., & Eales, J. (2011). Conceptualizing age-friendly communities. Canadian Journal on Aging = La revue canadienne du vieillissement, 30(3), 479–493. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0714980811000237

- Miller, G. R. (2011). Re-positioning age friendly communities: Opportunities to take AFC mainstream. https://policycommons.net/artifacts/1190561/re-positioning-age-friendly-communities/1743687/.

- Mazumdar, S., Learnihan, V., Cochrane, T., & Davey, R. (2018). The built environment and social capital: A systematic review. Environment and Behavior, 50(2), 119–158. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916516687343

- Moffatt, S., & Kohler, N. (2008). Conceptualizing the built environment as a social–ecological system. Building Research & Information, 36(3), 248–268. https://doi.org/10.1080/09613210801928131

- Nakamura, J. S., Hong, J. H., Smith, J., Chopik, W. J., Chen, Y., VanderWeele, T. J., & Kim, E. S. (2022). Associations between satisfaction with aging and health and well-being outcomes among older US adults. JAMA Network Open, 5(2), e2147797. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.47797

- Oswald, F., & Wahl, H. W. (2005). Dimensions of the meaning of home in later life. Home and Identity in Late Life: International Perspectives. 21–45.

- Ottoni, C. A., Sims-Gould, J., Winters, M., Heijnen, M., & McKay, H. A. (2016). “Benches become like porches”: Built and social environment influences on older adults’ experiences of mobility and well-being. Social Science & Medicine, 169, 33–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.08.044

- Peel, C., Sawyer Baker, P., Roth, D. L., Brown, C. J., Brodner, E. V., & Allman, R. M. (2005). Assessing mobility in older adults: The UAB study of aging life-space assessment. Physical Therapy, 85(10), 1008–1119. https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/85.10.1008

- Ritchie, J., & Spencer, L. (2002). Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In A. Huberman & M. Miles, The qualitative researcher’s companion (pp. 305–329). SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412986274.n12

- Roy, N., Dubé, R., Després, C., Freitas, A., & Légaré, F. (2018). Choosing between staying at home or moving: A systematic review of factors influencing housing decisions among frail older adults. PLoS One, 13(1), e0189266. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0189266

- Sarkisian, C. A., Hays, R. D., & Mangione, C. M. (2002). Do Older Adults Expect to Age Successfully? The Association Between Expectations Regarding Aging and Beliefs Regarding Healthcare Seeking Among Older Adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 50(11), 1837–1843. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50513.x

- Schulz, R., Wahl, H.-W., Matthews, J. T., De Vito Dabbs, A., Beach, S. R., & Czaja, S. J. (2015). Advancing the aging and technology agenda in gerontology. The Gerontologist, 55(5), 724–734. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnu071

- Seifert, A., Cotten, S. R., & Xie, B. (2021). A Double burden of exclusion? Digital and social exclusion of older adults in times of COVID-19. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 76(3), e99–e103. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbaa098

- Statistics Canada, S. C. (2016, July 8). Income of individuals by age group, sex and income source, Canada, provinces and selected census metropolitan areas. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1110023901.

- Tupper, S. M., Ward, H., & Parmar, J. (2020). Family presence in long-term care during the COVID-19 pandemic: Call to action for policy, practice, and research. Canadian Geriatrics Journal, 23(4), 335–339. https://doi.org/10.5770/cgj.23.476

- Turcotte, M. (2015, November 27). Profile of seniors’ transportation habits. Statistics Canada. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11-008-x/2012001/article/11619-eng.htm.

- van den Berg, P., Kemperman, A., de Kleijn, B., & Borgers, A. (2016). Ageing and loneliness: The role of mobility and the built environment. Travel Behaviour and Society, 5, 48–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tbs.2015.03.001

- van Hoof, J., Marston, H. R., Kazak, J. K., & Buffel, T. (2021). Ten questions concerning age-friendly cities and communities and the built environment. Building and Environment, 199, 107922. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2021.107922

- Webber, S. C., Porter, M. M., & Menec, V. H. (2010). Mobility in older adults: A comprehensive framework. The Gerontologist, 50(4), 443–450. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnq013

- Weil, J., & Smith, E. (2016). Revaluating aging in place: From traditional definitions to the continuum of care. Working with Older People, 20(4), 223–230. https://doi.org/10.1108/WWOP-08-2016-0020

- WHO. (2007). Global age-friendly cities: A guide. World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/43755.

- WHO. (2014). “Ageing well” must be a global priority. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news/item/06-11-2014–ageing-well-must-be-a-global-priority.

- WHO. (2021). Ageing and health. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health.

- Wiles, J. L., Leibing, A., Guberman, N., Reeve, J., & Allen, R. E. S. (2012). The meaning of “Aging in Place” to older people. The Gerontologist, 52(3), 357–366. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnr098

- Zhao, Y., Zhang, T., Dasgupta, R. K., & Xia, R. (2023). Narrowing the age‐based digital divide: Developing digital capability through social activities. Information Systems Journal, 33(2), 268–298. https://doi.org/10.1111/isj.12400