Abstract

This qualitative intuitive inquiry into residential care in Sweden discusses effects of social and spatial connections and disconnections during the Covid-19 pandemic. Interviews were carried out with 11 residents living in three residential care homes. Observations and spatial analyses complemented the interviews. The study investigated residents’ experience of the altered use of architectural space during the different phases of the coronavirus pandemic. Restrictions comprised, in general, that public areas were emptied, while residents were confined to their private apartments 24 hours a day. This created an entirely different caring architecture and challenged the usual care model of community. However, many residents said that staying in their apartments around the clock was an experience that was very similar to ordinary days in residential care, since they normally stayed long hours in their apartments. However, the residents’ disconnection from local information about the disease created a situation of great ambiguity and uncertainty about the progress of the pandemic and the state of the disease in the home. The interviewees claimed nevertheless that they had not been particularly worried about the situation. They had continued with normal leisure activities to make the time pass. It seems as though the disconnection from most of the spaces outside their apartments, as well as from staff, family and fellow residents, made it possible for them to disconnect themselves from awareness of the dangers of the disease caused by Covid-19.

Introduction

Many countries implemented similar measures to curb the spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virusFootnote1 among older people. In residential care, this included changed routines, restricted visits, reduced common activities and less socializing (Chee, Citation2020; Davies-Abbott et al., Citation2021; Ekoh, Citation2021; Klempić-Bogadi, Citation2021; Sims et al., Citation2022; Statz et al., Citation2022). Despite these restriction efforts, residents in residential care were disproportionately affected by the pandemic, with high rates of mortality. Sweden was no exception in this respect (Comas-Herrera et al., Citation2020). Of the about 19 000 Covid-19 fatalities in Sweden since the start of the pandemic, 7900 lived in residential care (Socialstyrelsen, Citation2023).

Many measures taken to limit the effects of the pandemic were spatial strategies, such as isolation and social distancing (Sims et al., Citation2022). Early in the pandemic, the Swedish Board of Health and Welfare presented examples of staff experiences of Covid-19 prevention; among these were spatial strategies (Socialstyrelsen, Citation2020). They involved the emptying of certain spaces in the residential care homes, and more intense use of others, such as the residents’ apartments. Older peoples’ responses to prevention measures are a topic in existing research (Connolly et al., Citation2022; Ho et al., Citation2022). Although space is mentioned or implicitly understood in some of these studies, it is often not the primary focus (Chee, Citation2020; Leontowitsch et al., Citation2021). The present research addresses this gap by exploring the design of residential care and its role in strategic use of space to prevent contagion.

In the initial analysis of the qualitative interviews, that are the empirical material for this study, a new pair of spatial concepts appeared: disconnection/connection. After looking into the literature about these, disconnection/connection were put in focus for understanding the spatial strategies and their consequences for the residents.

Disconnection (and connection)

Disconnection is not simply a stable state of severance but part of a process in which connection and disconnection are negotiated. Disconnection is not seen in isolation but rather implies that an existing connection has been disrupted or that disconnection might be an effect of connections elsewhere (Kolb, Citation2008). Thus, many researchers conceptualize the two together, indicating their interlacing, complementarity, mutual effects, and duality. “Dis/connections” could involve people, spaces, senses, material conditions that blend and oscillate in multi-scalar processes, changing over time (Sheringham et al., Citation2023). The duality that “connects and disconnects” involves technical, spatial and material elements, but also relations between people (Kolb, Citation2008). The corona-epidemic caused severe social disconnections (Provenzi & Tronick, Citation2020). Adaptations and changes in residential care caused distress, depression, fear and anxiety in residents (Chee, Citation2020; Davies-Abbott et al., Citation2021; Ekoh, Citation2021; Klempić-Bogadi, Citation2021; Leontowitsch et al., Citation2021; Statz et al., Citation2022). Residents’ negative experiences were often linked to disconnection from family, friends and fellow residents (Chee, Citation2020; Connolly et al., Citation2022; Ho et al., Citation2022). This paper explores how social and spatial disconnections were linked. An important insight here is that disconnections afford spaces of potentiality in which care can be constructed (Hanrahan, Citation2020). New connections can be established.

Space and Covid-19 in residential care

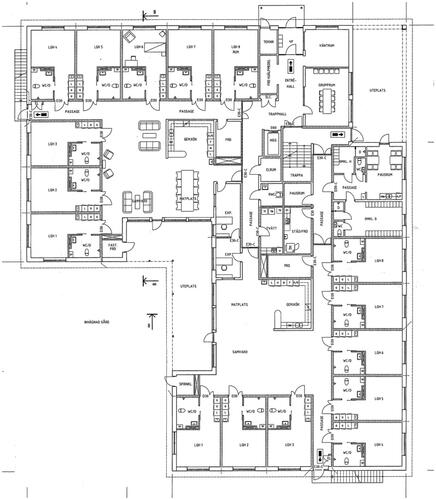

Residential care units in Sweden often consist of small apartments that are arranged along corridors and common areas for activities and meals (Johansson & Schön, Citation2021). Three residential care homes (RCH 1, 2 and 3) were included in the study, and all their units had this architectural structure. With a few exceptions, they contained common areas for the residents and bedsitting-rooms intended for a single tenant, with a small kitchenette, a hallway, and a bathroom.

The design is closely linked with a collective care model in which shared mealtimes and activities are expected to provide quality in the everyday, alongside care of the individual (Edvardsson et al., Citation2014). However, this highly valued resident community may also prove problematic when spatial strategies to prevent contagion need to be maintained. The care model is strongly embedded in and connected to the spatial design. The residents move throughout the day between the areas of common space and small apartments where they receive physical and social care. Common activities and meals take place in the common areas, and individual care is carried out in the residents’ private flats (For detailed descriptions of routines in residential care see Andersson, Citation2017; Nord, Citation2011). These connections between the care model and the design are characterized by a certain inertia and do not easily lend themselves to contain other care models, such as adaptations to Covid-19 (Sims et al., Citation2022). Nevertheless, space, even if physical, hard and tangible, is produced by social encounters and vice versa: social life produces space (Beyes & Steyaert, Citation2012). It is a “caring architecture,” in which care arises out of a flow of enactments of situations and spaces where residents, staff and artifacts contribute to different kinds of relationships and qualities (Nord, Citation2018; Nord & Högström, Citation2017). In these enactments, all components have agency – even dead material or agents without a will, such as a coronavirus (Thrift, Citation2008). Presumably, most would agree that the virus had substantial agency during the epidemic. In care homes, it disrupted the habitual, repeated activities that follow the architectural design and created new conditions for care and residents’ everyday routines in space. This is the situation in which disconnections and connections were negotiated ().

Methodology

This qualitative study is an intuitive inquiry (Anderson, Citation2011). Spatial issues related to Covid-19 guided the initial two cycles of an intuitive inquiry: the reflected background, the literature review, and the research questions. The concepts of disconnection and connection were treated as themes in an inductive analysis in Cycle 3.

The study was conducted in three residential care homes in a middle-sized town in southern Sweden. Homes with a somatic approach were invited to participate. Due to the challenge of interviewing people with dementia, homes dedicated for them alone were, thus, excluded.

Data collection methods

Qualitative data was collected via individual semi-structured interviews, observations and photographs of the environment, researcher field notes and architectural drawings. Participating residents were recruited by the unit manager, who had given consent to the study. She was asked to choose participants who could understand the implications of participation in the interviews. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 11 residents living in six different units. Each unit in the study contained between seven and nine apartments with a floor area of between 26 and 31 square meters. Nine of the interviewees were women and two were men, and they had lived in the home for between five months and four years. The oldest interviewee was 96 and the youngest 60. They all suffered from conditions that demanded around-the-clock care (For details see ). The study received ethical approval from the relevant authority. All participants agreed in writing to participate anonymously and voluntarily. All of the interviews were conducted between February and October 2022. They lasted between 21 and 97 minutes and were conducted in the residents’ own apartments and on walks through the residential care home during which the interviewee showed the spaces in the residential care home to which the person had referred during the interview. Topics in the interviews included spatial and other changes during the pandemic, the interviewees’ experiences of these, and their own strategies to avoid contagion. In five cases, tours were not carried out, either because the interviewee had declined or for a practical reason. Interviews and walking conversations were recorded and transcribed verbatim. Observations during each tour focused on indoor and outdoor architectural spaces. The researcher made fieldnotes and took photographs of presented spaces and things using a mobile phone camera. Architectural drawings of each of the residential care homes were obtained from the city planning office and a real estate owner of one of the homes.

Table 1. Interviewees, details.

Analysis

The analysis in this study focused on changes caused by the coronavirus, such as altered use and changed significance of space and things and affective responses to new situations of spatial and material enactments. The analytical process started with data immersion, in which all the generated material was read, reviewed, and reflected on several times. Connection and disconnection emerged as two important concepts and these were further explored by structured descriptive coding. The intuitive part of the analysis was akin to emphatic identification in which researchers “inhabit the lived world of another person or object of study” (Anderson, Citation2011, p. 248). The author tried to put herself in the situation of the residents. This drew the residents’ experience of the situation closer to the researcher’s imagination and contributed to the interpretation of the results.

Results

As was expected, the interviews showed that the organization of everyday life and care changed radically in the residential care homes in the study after the appearance of the coronavirus. Changes included new uses of spaces, modified caring practices, and altered social relations. The collective care practices with common activities and meals were totally abandoned for periods of time. Many of the modifications made were aimed at distributing people differently in new spatial enactments by imposing on residents restricted movement, isolation, and social distance (). These spatial strategies had the effect that some existing spatial connections were disconnected while others were more strongly reinforced.

Applied spatial strategies

A major spatial strategy was isolation in the apartments. The residents were instructed or effectively recommendedFootnote2 by the staff to stay in their own apartments. One woman recalled in an interview: Yes, well, then we were all closed up in our rooms (Woman, 95, RCH 2). One woman had been asked by the staff to keep the door closed. Don’t let anyone in (Woman 77, RCH 1). Another woman made a similar comment: Yes, we were supposed to stay inside, not go out and meet with others (Woman 90, RCH 1). Not meeting others included family and friends; their visits were totally banned. We were forbidden to go out, and my relatives weren’t allowed to come in; they completely shut off the unit (Woman 60, RCH 1). Thus, the connection between the residents and their private spaces became stronger and more intense.

If the residents chose to leave their apartments, their movements were restricted. Movements in corridors were directed in new ways by the disconnection of walking paths residents usually used. Under normal circumstances, they visited common spaces for meals, coffee breaks and activities. The use of the dayroom was largely prohibited during periods of the pandemic. This became then a disconnected space.

In all care homes, residents were instructed to maintain social distance from each other and from members of staff. The 74-year-old woman talked about restrictions in common spaces: people weren’t allowed to sit too close together. During the two pandemic summers, temporary reconnections of previously disconnected areas were introduced. Staff tried to compensate for the restricted visits, and isolation in the apartments and controlled movements in common space by offering activities outside, especially meals. One woman remembered that last year they [the staff] organized a lot of social gatherings with coffee and cake (Woman 80, RCH 3). Meetings with family and friends were permitted outdoors. One man recalled that, [y]es, we [my brother and I] had to meet each other outside (Man, 70, RCH 3).

Disconnecting spatial strategies also disconnected relationships between residents and family members and between residents. The supporting idea of the resident community, which is at the core of the care model in residential care, was clearly challenged. How these changes were negotiated and managed by the residents is presented in the next section and supported with the two concepts connections and disconnections.

Connections: an everyday life with strong boundaries

The interviewer asked the 80-year-old-woman where she had spent the previous two years, during the pandemic. She sketched a very restricted existence comprising a few square meters: Well, either in the chair [the wheelchair] or in the bathroom, and otherwise in bed (Woman, 80, RCH 3). The connections with the apartment space, furniture and other artifacts became stronger. The spatial possibilities for the residents to accommodate everyday life in the apartments during the pandemic were limited. It is reasonable to assume that problems with the apartments became more urgent when they were used more intensively. The small size of the apartments arose as an issue in interviews. Several interviewees believed that “apartment” was a misnomer since it was no more than a room. Every interviewee called them “rooms,” not “apartments,” which they in fact formally are. The 90-year-old woman put forward in interview that the size had bothered her already when she had moved in.

The only thing I can’t really get my head around is that they call the rooms “apartments.” I suppose I was a little surprised and irked by that. (Woman 90, RCH 1)

She also observed that the apartment’s limited size made arranging the furniture difficult, remarking that there aren’t many changes [one can] make in a room this small. One effort to expand living space was to use the private balcony more with which the apartments in one of the studied RCHs were equipped. The 70-year-old man had moved the bed in his apartment to improve access to the balcony. Except for this effort, few other interviewees had furnished their living spaces differently or bought any new things in response to the pandemic, although some activities had become awkward. Residents were served all meals in their own apartments, and not in the dining room, which was the rule according to the normal care model. One woman said that they [the staff] brought in trays to everyone (Woman 77, RCH 3). Having meals in the apartment was inconvenient, as some apartments lacked dining tables. Two interviewees did not even have coffee tables. One interviewee had added a small table and chair in the hallway. Another used a garden table because it was easier to move than an ordinary table. Then [when meals were served] I sat here at my little round garden table (Woman 80, RCH 3).

The furnishing options were limited, as were the leisure activities suitable when alone; these included watching TV or listening to the radio. One woman said that one just tried to get time to pass. If there was something on TV you watched that, but there’s been too much sports on (Woman 95, RCH 2). Other interviewees kept themselves busy with jigsaw puzzles and crosswords. They read newspapers and books or listened to audio books. The 95-year-old woman seemed to consider herself fortunate because of the reading habits she had long since maintained. I’ve always liked reading, so I’ve read an awful lot of books [during the pandemic]. For others it was more difficult. The 74-year-old woman said that she could no longer read.

All residents had family they missed: for instance, siblings, children and grandchildren. Some had friends. This was the most difficult aspect of isolation to endure. There weren’t many visits from relatives, it was pretty much shut down here. They weren’t allowed to come, so I guess that was actually one drawback (Woman 96, RCH 3). While residents were disconnected to a large extent from face-to face connections they tried to cultivate other means for that in their rooms. Telephones were used more than usual. Many interviewees said that they spoke with family and friends, sometimes daily. One woman recalled:

I had so many friends, I had a book club and a few of those groups of old friends who used to meet up and they called, and called, and called and called, but we could almost never meet. (Woman 80, RCH 3)

This might be a reason why some interviewees stated that while they had spent more time in their apartments than usual, the difference from normal, everyday life was not that dramatic. Interviews revealed that the residents viewed this austere situation with acceptance. The 96-year-old woman said that I usually spend quite a lot of time inside [my apartment] anyway. Interviewees’ views and experiences varied only minimally. Many claimed that life during the pandemic had been the same as before it started. I just remember there was a lot about that you couldn’t go out [during the pandemic]. But here I guess everything was the same as always, I don’t see any difference, actually (Woman, 90 years, RCH 1). As boring as always, was the 80-year-old man’s short assessment. It couldn’t be any more monotonous, he added. Acceptance of the situation seemed to be a generally applied strategy among the interviewees. You can get used to nearly everything, the 96-year-old woman said. She continued,

I didn’t actually have any particular experience [of the pandemic]. I found it pretty much alright. No, I didn’t think there was any major difference. (Woman 96, RCH 3)

Another woman described the situation thus:

Since things are as they are, and were as they were [laughs], perhaps it wasn’t so hard for me personally to adapt, in part because I’m used to being alone and working on my own and keeping myself busy with the radio and TV and books and the like. (Woman 80, RCH 3)

If modifying one’s everyday space during the pandemic was not possible, acceptance seemed to be a general strategy for handling a situation in which the possibilities to encounter the dangers of the coronavirus were limited. It appears that residents did not find this very problematic, as being sequestered in the apartments was not seen as a significant disconnection from normal, everyday life. The results show that interviewees found that life during the pandemic had proceeded almost as usual, with the exception of not meeting family.

Disconnections: a state of growing ambiguity

One woman stated that the measures against the pandemic came on slowly and stealthily; she suggested that residents discovered rather unexpectedly that restrictions had been implemented.

There wasn’t so much fanfare; instead it kind of crept up: Now you can’t do that, and now you can’t go outside … and then there were no really direct rules [communicated]. Instead, one just slowly [understood]: Well, oh, is it prohibited to …? Aha, then we won’t do that. (Woman, 77, RCH 3)

Some staff messages were communicated verbally, while others were transmitted with things. Material artifacts were used to convey and perhaps reinforce messages about disconnected spaces and new connections between people, artifacts, and spaces. They [the staff] moved the chairs because that was the easiest thing to do (Woman 60, RCH 1). When common areas were reconnected during periods, the chairs around the tables in the dining area, living rooms and common balconies were positioned at a greater distance from one another. Door management seemed to be an important measure for conveying messages about disconnected or connected spaces. Residents discovered that doors that were normally open were suddenly closed, and vice versa – doors that were normally closed could be open. One interviewee said that [t]he door out there that leads to the sitting room corridor was suddenly locked. It was always open before (Woman 77, RCH 3).

While some restrictions were introduced gradually, disconnection from family visits was introduced almost immediately at the start of the pandemic – but this was also done in a way that took this woman by surprise.

Receiving visitors was prohibited almost right away. “It was just, I heard from my daughter, I was talking on the phone with her: ‘Are you coming on Sunday?’ ‘No, we’re not allowed,’ she [the daughter] said.” (Woman 77, RCH 3).

Clearly, the woman did not know that visits from outside had been banned. Abruptly imposed and removed rules, involving negotiation between connections and disconnections, between what was allowed and what was prohibited, persisted throughout the whole epidemic in response to the waves of the pandemic. This may have caused uncertainties about which rules were applicable and whether or not the pandemic was still ongoing.

Other ambiguities appeared in interviews. All interviewed residents claimed that they had followed staff instructions and recommendations. One woman believed that this compliance had contributed to there being only a few cases of Covid-19 in the home where she lived.

I’ve said many times that we were spared because of our carefulness, and maybe some luck, too. Because most people didn’t have many visitors. [Judging from] what I believe at least or have seen. (Woman 80, RCH 3)

As the last sentence implies, the statement was based on sheer optimism, as she did not know with any certainty how many visits her fellow residents had received, nor the de facto number of cases in the unit. Ten out of eleven interviewees maintained that there had been only a few cases of Covid-19 in the units, if any, and no or very few deaths.Footnote3 The 60-year-old woman who helped with setting the table in the common dining room was, however, of the opposite opinion; she maintained that everyone who did not appear for meals (she counted the plates) was laying ill in their apartments.

I usually help set the tables, so I know the number [of sick residents] When they were ill, there were only about three of us eating here. (Woman 60, RCH 1)

This thus contradicted all other information that appeared in the interviews. The woman most probably overinterpreted the number of people who were sick and did not take into consideration that they could simply have chosen to eat in isolation, as they were asked to do so. Whether or not the other residents underestimated the number of cases, the fact that there were residents who believed there had been practically no cases, as well as residents who believed there had been many cases, indicates that residents lived in a state of uncertainty and guessing during the pandemic as a consequence of being disconnected. In reality, locked up in their rooms, they had no overview over the situation, no insight into what was actually happening in the unit. The 96-year-old woman was the only interviewee who stated explicitly that she was unsure of the number of Covid-19 cases in the unit. No, I don’t know, because… No, I actually can’t… [say how many cases there were]. Usually, the staff was the only source of information regarding cases in the units during the restrictive periods. However, access to staff seemed to be more limited than usual, implying a disconnection to some extent also from care, as the pandemic had placed a heavier workload on the staff. One woman noted in the interview that but then they [the staff] say “Well then, you can just call if you need help,” but it isn’t that easy when they’re busy with everything and they’re understaffed. (Woman, 80, RCH 3)

The 96-year-old woman, who was uncertain about how many cases there had been, voiced some mistrust regarding the information she was given by the staff. No, actually what I think is that they [the staff] went around every day and practically boasted that there hadn’t been any [cases]. If they weren’t lying to us, because you really never know. The possibility that the staff did not inform about deaths in the unit so as not to worry the residents is not entirely unfounded. The resident was, thus, disconnected from information too.

Another condition that increased ambiguity was the spatial disconnection that limited contact between residents. Limited contact may also have been habitual to some extent. While the interaction between residents varied, minimal contacts seemed to be the norm. The 96-year-old woman mentioned interaction with fellow residents in her interview, however, her experience seemed to be an exception; few of the interviewees had contact with others. The 77-year-old woman had lived in the home for three years at the time of the interview, but she had never visited another resident’s apartment. Two of the women interviewed complained about the usual silence at mealtimes:

If you come here while we’re eating for example, it can be silent as a grave. Not a word being uttered. And no one, I think… Yes, [one would hope for] some polite conversation, How are you today?’ So I preferred to go in here [in my apartment] and sit and listen to the radio or the TV, or read, instead of sitting out there in that deadly silence, or else ask my neighbors those questions. (Woman, 80, RCH 3)

It seems as though the spatial disconnections and limited exchanges made it possible to disconnect oneself from the disease and the frightening seriousness of it. The 96-year-old woman talked about this disconnection, stating that [y]es, one distanced oneself in a way, more or less: No, it [the pandemic] has nothing to do with us. In effect, there was little that reminded the residents that a terrible pandemic was raging beyond the walls of their apartments. Most said that they had tried to not to worry too much about the pandemic and the recommended instructions.

One of the participants, the 70-year-old man, had experiences that differed quite substantially from those of the average interviewee. He was the only interviewee who had left the residential care home during the pandemic and maintained contacts outside. He was also the only participant who had contracted Covid-19 and was subsequently hospitalized for eight weeks. He declared explicitly that he had been afraid of becoming infected after that. I was [afraid]! And I have had it [Covid-19]. I didn’t know how hard a blow it would be. He had also lost three friends to Covid-19. His freedom seemed to have challenged the belief that the disease was not that serious. The disconnection from the home he had chosen gave him more connections outside, for better and for worse. It also seemed to have given him greater respect for the disease than the average interviewee.

One woman mentioned TV news as a reminder of the seriousness of the disease. I suppose one followed along quite a bit to see how it was going. Maybe watching [on TV]. One thought of course about all of the people who were ill. Who got that awful [Covid-19] (Woman 90, RCH 1). However, it seems as though the information from outside was not powerful enough to seriously disturb most of the residents. It is possible to imagine that perhaps the family censured the information in phone calls so as not to worry their parent or grandparent, who could not be present to comfort the relative. In addition, perhaps other topics of conversation were preferable both on the telephone and when the opportunity to meet in person finally appeared during the summer months.

In conclusion, many factors seemed to have contributed to a situation in which it was possible to disconnect oneself from the dangerous disease by spatial isolation and limited contacts and information (see for a summary). Interlaced connections and disconnections may have facilitated not thinking too much about the pandemic.

Table 2. Spatial strategies and aspects of connection/disconnection negotiation.

Discussion

The results show that the coronavirus disturbed all routines and everyday practices and altered the distribution of people in space and the use of spatial resources as consequences of spatial disconnections and connections in the home during the pandemic. Spatial strategies that were introduced to curb the contagion were similar to restrictions presented in existing research, including isolation, control of movements, and social distancing in the home or apartment (Sims et al., Citation2022). The mutuality between connect and disconnect became obvious in the strategies to counter the Covid-19 contagion (Andersson, Citation2017; Hanrahan, Citation2020; Kolb, Citation2008). Disconnection and connection, spatial as well as social, appeared as negotiations over time during the pandemic. Social disconnections were often an effect of spatial disconnections and the varied recommendations. Contacts with staff, residents and family fluctuated over seasons and the phases of the pandemic. These processes created a situation of ambiguity for the residents over time and may have contributed to uncertainty about the state of the pandemic.

A new caring architecture appeared in which care practices changed from communal to more privatized (Nord & Högström, Citation2017). Public areas were emptied, while people were referred to private ones. The residents were recommended to stay in their apartments, and they were largely disconnected from public areas, although that varied to some extent over time. Changes molded a new care model in which the highly valued community appeared as a void; an empty space in which care was disconnected or rearranged (Hanrahan, Citation2020). New care practices appeared. However, the inert spatial model did not offer many possibilities or broader gestures to prevent the contagion other than altered distribution of residents in existing space according to the logic “more of the same,” primarily staying in their private apartments 24 hours a day. The structure and content of the daytime hours during the restricted periods were similar to the residents’ days during the pandemic described in the study by Leontowitsch et al. (Citation2021). A surprising result of this study is that the residents stated that isolation was not very different from ordinary everyday life, since they normally spent quite a lot of time in their apartments. The usual long hours in resident apartments, often due to conditions or self-isolation, are congruent with other research (Andersson, Citation2017; Nord, Citation2011, Citation2013). Residents accepted the situation of isolation and being disconnected from the community and tried to entertain themselves with ordinary leisure activities.

The few artifacts and furniture items in the apartments and the limited square meterage refused to adapt to the situation of stronger spatial connection the long hours implied. Anderson and colleagues (2020) warn that while isolation in small private apartments may minimize contagion, it may also be detrimental to residents’ everyday life. This did not seem to be a relevant warning in this study, even though the residents did raise a few complaints. The very strong negative feelings about the pandemic that other research has shown did not appear in this study (Chee, Citation2020; Davies-Abbott et al., Citation2021; Ekoh, Citation2021; Klempić-Bogadi, Citation2021; Leontowitsch et al., Citation2021; Statz et al., Citation2022). Residents complained about the small size of the apartments and other problems with their possessions. The strong connection with the apartment made them struggle more than usual with both the restrained size and the limited number of artifacts. Isolation in the apartments made problems with physical space more urgent when coalesced into a recalcitrant enactment of the everyday during the pandemic. It is worthwhile to remind the reader that this is the situation in which the residents allegedly find themselves on a daily basis in the absence of a pandemic.

The spatial connections and disconnections and their contribution to feelings of safety or unsafety is obvious when this study is compared to other similar studies (Chee, Citation2020; Connolly et al., Citation2022). The residents in Chee’s (Citation2020) study felt confined to a limited space, trapped and unsafe. They did not have access to private space but only to areas they shared with fellow residents, possibly exposing them to a certain contamination risk. The situation was quite different for the residents in this study. Instead, they shared the experience of being safe with the residents in the study by Connolly et al. (Citation2022), who were isolated in their single rooms. This study’s participants seemed to feel that they would be secure if they followed the recommendations and stayed in their apartments. Uncertainty about the pandemic appeared in the study by Chee (Citation2020). She showed how people in residential care in Malaysia were uncertain about the magnitude of the pandemic outside, from which they were disconnected, and that this contributed to a feeling of being unsafe; disconnection from information made the study participants withdraw into themselves. Information about the disease was also limited in this study. Somewhat contradictorily, it seems as though while the social disconnection from family and fellow residents in this study exacerbated the situation of uncertainty related to the disease and its consequences in the unit, the residents felt, nevertheless, secure. The spatial disconnection that isolation caused may have contributed to the residents being able to weather adversities with stoic calmness, trying not to allow themselves to be upset. The disconnection from the public areas and the isolation into the private apartment in this study may have offered a withdrawal from the ambiguity of the disease. Isolation could thus disconnect residents from the insight into the pandemic.

Acknowledgement

The fieldwork administration and interviews were carried out by Senior Lecturer Kristina Tryselius, Department of Health and Caring Sciences, Linneaus University, Sweden.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Hereafter “the coronavirus.”

2 Unlike other countries, Sweden never enacted a total lock-down. The general recommendation was to maintain a two-meter distance from others in public, and it relied on peoples’ responsible contribution, not enforcement. ‘In Sweden, disease control centers around voluntary preventative efforts’ (SOU, Citation2020:80, p. 293. Translation by Justina Bartoli.).

3 This might have been a correct assessment of the state in the unit. The regions in southern Sweden were struck later in the pandemic, when rules and regulations were already in place. They thus recorded fewer cases of the disease and fewer deaths (Johansson & Schön, Citation2021).

References

- Anderson, R. (2011). Intuitive inquiry: Exploring the mirroring discourse of disease. In F. J. Wertz, K. Charmaz, L. M. McCullen, R. Josselson, R. Anderson, & E. McSpaden (Eds.), Five ways of doing qualitative analysis: Phenomenological psychology, grounded theory, discourse analysis, narrative research, and intuitive inquiry (pp. 243–276). The Guilford Press.

- Andersson, M. (2017). Normative and relational aspects of architectural space. In E. Högström & C. Nord (Eds.), Caring architecture: Institutions and relational practices (pp. 127–142). Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Beyes, T., & Steyaert, C. (2012). Spacing organization: Non-representational theory and performing organizational space. Organization, 19(1), 45–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508411401946

- Chee, S. Y. (2020). COVID-19 pandemic: The lived experiences of older adults in aged care homes. Millennial Asia, 11(3), 299–317. https://doi.org/10.1177/0976399620958326

- Comas-Herrera, A., Zalakaín, J., Lemmon, E., Henderson, D., Litwin, C., Hsu, A. T., Schmidt, A. E., Kruse, G. A. F., & Fernández, J.-L. (2020). Mortality associated with COVID-19 in care homes: international evidence. Article in LTCcovid. org, international long-term care policy network (vol. 14). CPEC-LSE.

- Connolly, M., Duffy, A., Ryder, M., & Timmins, F. (2022). ‘Safety first’: Residents, families, and healthcare staff experiences of COVID-19 restrictions at an Irish residential care centre. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(21), 14002. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114002

- Davies-Abbott, I., Hedd Jones, C., & Windle, G. (2021). Living in a care home during COVID-19: A case study of one person living with dementia. Quality in Ageing and Older Adults, 22(3/4), 147–158. https://doi.org/10.1108/QAOA-02-2021-0024

- Edvardsson, D., Petersson, L., Sjogren, K., Lindkvist, M., & Sandman, P. O. (2014). Everyday activities for people with dementia in residential aged care: associations with person‐centredness and quality of life. International Journal of Older People Nursing, 9(4), 269–276. https://doi.org/10.1111/opn.12030

- Ekoh, P. C. (2021). Anxiety, isolation and diminishing resources: The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on residential care home facilities for older people in south-east Nigeria. Working with Older People, 25(4), 273–282. https://doi.org/10.1108/WWOP-01-2021-0001

- Hanrahan, K. B. (2020). The spaces in between care: Considerations of connection and disconnection for subjects of care. Area, 52(2), 244–250. https://doi.org/10.1111/area.12486

- Ho, K. H., Mak, A. K., Chung, R. W., Leung, D. Y., Chiang, V. C., & Cheung, D. S. (2022). Implications of COVID-19 on the loneliness of older adults in residential care homes. Qualitative Health Research, 32(2), 279–290. https://doi.org/10.1177/10497323211050910

- Johansson, L., & Schön, P. (2021). MC COVID-19. Governmental response to the COVID-19 pandemic in long-term care residences for older people: Preparedness, responses and challenges for the future: MC COVID-19. working paper 14/2021.

- Klempić-Bogadi, S. (2021). The older population and the COVID-19 pandemic: The case of Croatia. Stanovništvo, 59(1), 31–46. https://doi.org/10.2298/STNV210406003K

- Kolb, D. G. (2008). Exploring the metaphor of connectivity: Attributes, dimensions and duality. Organization Studies, 29(1), 127–144. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840607084574

- Leontowitsch, M., Oswald, F., Schall, A., & Pantel, J. (2021). Doing time in care homes: Insights into the experiences of care home residents in Germany during the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. Ageing & Society, 2021, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X21001161

- Nord, C. (2011). Architectural space as a moulding factor of care practices and resident privacy in assisted living. Ageing and Society, 31(6), 934–952. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X10001248

- Nord, C. (2013). A day to be lived. Elderly peoples’ possessions for everyday life in assisted living. Journal of Aging Studies, 27(2), 135–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaging.2012.12.002

- Nord, C. (2018). Resident-centred care and architecture of two different types of caring residences: A comparative study. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 13(1), 1472499. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482631.2018.1472499

- Nord, C., & Högström, E. (2017). Introduction. In E. Högström & C. Nord (Eds.), Caring architecture: Institutions and relational practices (pp. 7–17). Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Provenzi, L., & Tronick, E. (2020). The power of disconnection during the COVID-19 emergency: From isolation to reparation. Psychological Trauma, 12(S1), S252–S254. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000619

- Sheringham, O., Ebbensgaard, C. L., & Blunt, A. (2023). ‘Tales from other people’s houses’: Home and dis/connection in an East London neighbourhood. Social & Cultural Geography, 24(5), 719–737. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2021.1965197

- Sims, S., Harris, R., Hussein, S., Rafferty, A. M., Desai, A., Palmer, S., Brearley, S., Adams, R., Rees, L., & Fitzpatrick, J. M. (2022). Social distancing and isolation strategies to prevent and control the transmission of COVID-19 and other infectious diseases in care homes for older people: An international review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(6), 3450. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19063450

- Socialstyrelsen. (2020). Arbetssätt vid covid-19 hos personer med demenssjukdom i särskilda boendeformer för äldre – praktiska förslag om arbetssätt till personal och arbetsledning [Working with dementia patients in residential care for older people in the time of Covid-19 – practical suggestions for working methods for staff and management]. National Board of Health and Welfare.

- Socialstyrelsen. (2023). Statistik om covid-19 och coronapandemin [Statistics about covid-19 and the corona epidemic]. Retrieved from https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/statistik-och-data/statistik/statistik-om-covid-19/.

- SOU. (2020:80). Äldreomsorgen under pandemin [Eldercare during the pandemic]. Swedish Governmental Report.

- Statz, T. L., Kobayashi, L. C., & Finlay, J. M. (2022). ‘Losing the illusion of control and predictability of life’: Experiences of grief and loss among ageing US adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ageing & Society, 2022, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X21001872

- Thrift, N. (2008). Non-representational theory: Space, politics, affect. Routledge.