Abstract

This paper draws analytical attention to the debates on legal pluralism to understand Mapuche-Williche expressions of water rights in southern Chile in the context of Chile’s environmental institutions, based on a case study of the long-standing conflict over the hydroelectric power plants developed by the Norwegian state-owned company Statkraft on the Pilmaiquén River. The analysis focuses on the hermeneutical problems that emerge from the process through which the Chilean environmental institutions translated the dense cosmogony of the Mapuche-Williche communities around the Pilmaiquén River during the environmental assessment of the Osorno Hydroelectric Power Plant, through the category of a “site of cultural significance”, and the impacts that this process has had over time. I argue that, although the category of site of cultural significance made the meaning of water in the normative world of the Mapuche-Williche communities of this territory commensurable, understandable, and partially comparable, it deprived it of its complex meanings, giving rise to various equivocations that imply forms of epistemic injustice of a hermeneutic type.

Introduction

This paper seeks to draw analytical attention to the debates around the recognition of legal pluralism to understand Mapuche-Williche expressions of water rights in southern Chile and their implications in the context of environmental regulation and institutions. Conflicts over water in Mapuche territory (Wallmapu) have generally involved large and small hydroelectric projects, where issues of water governance, environmental regulation and recognition of indigenous peoples’ rights intersect (Bauer Citation2015, 156; Kelly Citation2019b; Kelly Citation2018a).

For decades, water governance and management, especially in the Andean region, has offered a fertile field of study for examining constellations of locally expressed norms, where diverse normative systems overlap in time and space, within and across state borders (von Benda-Beckmann, von Benda-Beckmann, and Spierz Citation1997; Prieto Citation2012; Prieto Citation2014). However, in redefining ways to regulate and control land and water, state and transnational legal frameworks, as well as water infrastructure (including projects to exploit the hydropower potential of watersheds), have generally involved a disruption of existing local land and water rights systems (Roth, Boelens, and Zwarteveen Citation2015, 457). In addition, the development of water projects and infrastructure has traditionally been dominated by economic and technical forms of scientific expertise that have little regard and respect for local knowledge and existing systems of land and water management and allocation (Kelly Citation2019b, 224–226).

The Chilean Water Code, in force since 1981, has been considered a paradigmatic example of a neoliberal model of water management, by allowing the privatization of this common good and its monopolization for speculative purposes (Bauer Citation2004). Likewise, the environmental reforms that have been promoted in Chile since the 1990s have followed the logic of having laws that allow the commercialization of natural resources for the country’s insertion into global markets (Tecklin, Bauer, and Prieto Citation2011; Kelly, Guerra-Schleef, and Valdés-Negroni Citation2021).

On the other hand, at least since the 1990s, the efforts of the Mapuche communities and organizations have focused on making visible the conflicts between community uses of the territory and private interests over the waters in those territories, particularly in the context of the promotion of hydroelectric power plants. At that time, national and international attention was focused on Ralco and Pangue hydroelectric power plants in the Pewenche territory of Alto Biobío. Since then, the discursive registers of the Mapuche communities have evoked the sacred character of the bodies of water that will be affected, as well as the relationship between the territory and the different human and non-human beings that inhabit it (Llancaman Citation2020). This emphasis from the Mapuche point of view has been shared in many cases such as Neltume, Pilmaiken, Trankura and Truful Truful, to name just a few (Llancaman Citation2020; Cardoso and Pacheco-Pizarro Citation2021).

At this point, a central debate arises on legal pluralism in Chile, which is related to how to seriously consider the diverse local systems of rights without eliminating or subordinating them, without leveling their differences with the logically ordered and hierarchical state laws (Cardoso and Pacheco-Pizarro Citation2021). This allows me to focus on the question that -as a human rights defender- seems central to me to understanding the challenges faced by indigenous peoples as they attempt to make their rights systems legible in the current Chilean legal context: How do Mapuche communities navigate the Chilean legal system in deciding when and how to translate fundamental aspects of their normative systems and epistemological frameworks into the legal categories of the Chilean state? What are the consequences, and how are they distributed among groups of humans, non-humans and more-than-humans?

To address these questions, this paper examines the conflict surrounding the hydroelectric power plants developed by the Norwegian state-owned company, Statkraft, in the Mapuche-Williche communities’ territory of the Pilmaiquén River (hereafter the “Pilmaiken case”). This case provides an example of legal pluralism from which to explore the complexity and plurality expressed in the policies of implementation of indigenous rights in Chile after the ratification of International Labor Organization (ILO) Convention 169 (2008). This case was chosen because it constitutes a conflict of long duration, which has extended over 17 years, representing a longitudinal opportunity to observe how ILO Convention 169 has been domesticated and adapted to a diversity of local legal practices, as well as the strategies of accommodation and resistance promoted by the different actors (indigenous, state and companies) involved in the governance of water in this country.

I focus my analysis on the hermeneutic problems that emerge from the process through which the Chilean environmental institutions translated the dense cosmogony of the Mapuche-Williche communities around the Pilmaiquén River and the Ngen Mapu Kintuantü during the environmental assessment of the Osorno Hydroelectric Power Plant (2007–2009), through the category of “site of cultural significance”, and the impacts that this process has had over time. I argue that although the category of site of cultural significance made the meaning of water in the normative world of the Mapuche-Williche communities of this territory commensurable, understandable, and partially comparable, it deprived it of its complex meanings, giving rise to what Castro identifies as an “equivocation” (Castro Citation2004). I suggest this translates into a form of hermeneutic epistemic injustice (Fricker Citation2007).

To develop this argument, this article is organized in five sections. First, I present the methodological approach guiding this research, which was based on collaboration guided by the Aylla Rewe Ngen Mapu Kintuantü, while I worked as a lawyer for this traditional Mapuche-Williche organization. Second, I develop the theoretical framework, which is informed by a socio-legal approach from legal pluralism to understand the forms of epistemic-hermeneutic injustice at the heart of this case. To present the hermeneutical problems and injustices that arise from the process of cultural translation between normative orders in this case, I use concepts that have been developed in the anthropology of legal culture and equivocation. Third, I present my case study. I begin with some historical background on the colonization process of the Mapuche-Williche territory between the Pilmaiquén and Chirre rivers; and then contextualize the concept of ngen and the meaning of water to the particularities of the AzMapu (or Mapuche law) of this territory. I examine how, through the category of site of cultural significance, the dense cosmogony around the Ngen Kintuantü and the Pilmaiquén River is translated during the environmental assessment of the Osorno Hydroelectric Power Plant and the impacts of this process over time. Fourth, I discuss the limits of this translation process, exploring the misunderstandings and equivocations that are made explicit in this case. Finally, this paper ends with the main conclusions.

Methodological approach

The data and reflections presented here are the result of a collaborative research with ancestral authorities and Mapuche-Williche communities that are part of the Aylla Rewe Ngen Mapu Kintuantü, an autonomous indigenous organization with which I worked for 8 years as a lawyer, accompanying their legal strategies in defense of the Pilmaiquén River and the Ngen Mapu Kintuantü (guardian and ruling entity of this territory). As a non-indigenous Chilean lawyer, I arrived in this territory in 2015, as part of the legal team of Observatorio Ciudadano, a non-governmental organization dedicated to the defense of the collective rights of indigenous peoples in Chile. There I met Machi Millaray Huichalaf, spiritual authority of this territory and defender of the Pilmaiquén River and the Ngen Kintuantü and began to become actively involved in the processes and legal strategies analyzed in this paper.

The Aylla Rewe Ngen Mapu Kintuantü is a political, social, spiritual, and cultural alliance of ancestral authorities and Mapuche-Williche communities (lof) of this territory, which has rearticulated to, among other things, resist hydroelectric interventions in the Pilmaiquén River. This organization is connected to an ancestral form of management and socio-political alliance of the territory around an Aylla rewe, which operates at the territorial scale of this basin. An Aylla rewe generally includes nine rewe. The latter are sacred spaces located in a gillatuwe, lepuntuwe or paliwe, among other places where prayers and ceremonies are held (Machi Millaray Huichalaf, Oral communication, November 1st, 2023). Therefore, the Aylla Rewe Ngen Mapu Kintuantü is both a political and a spiritual organization. Likewise, its members are part of the Mapuche People, which is the largest indigenous people in both Chile and Argentina. Specifically, they identify themselves as Williche, which corresponds to the southern part of this indigenous people, which has occupied since time immemorial the Futawillimapu (or “great southern territory”, in mapuzungun), which covers the extensive territorial space between the Toltén River, in the north, and insular and continental Chiloé, in the south (Comisión de Verdad Histórica y Nuevo Trato con los Pueblos Indígenas Citation2008, 443–444).

The research was guided by a case study (Yin Citation2014) in the Mapuche-Williche territory of Pilmaiquén, with the aim of understanding the territorial-legal development of conflicts over indigenous rights in Chile. Because my first approach to this territory was not as a researcher, and my interest in critically analyzing what I was observing developed as I began to collaborate as a defense lawyer, this work was intended to support the legal strategies of territorial defense of the Aylla Rewe Ngen Mapu Kintuantü. This was part of the working agreement with the ancestral authorities of this organization, which deeply influenced the methods we finally applied to answer my main research question (Kovach Citation2020). Thus, the qualitative case study presented here emerged to follow up on the emerging conflicts and critically reflect on the hydroelectric power plants and the corresponding legal cases.

The methodological strategy was data triangulation, which implies that the researcher diversifies and interweaves his sources of information. This makes it possible to avoid a single point of view and obtain more solid and reliable results, since each method can compensate for the limitations of the others (Denzin Citation2009). This strategy seeks to increase the validity and reliability of the findings, as well as to provide a more complete and deeper understanding of the phenomenon studied (Patton Citation1980, 108–109). A combination of methods were used, including legal analysis and review of administrative (environmental assessments of the projects, administrative appeals, land claim proceedings) and judicial files of the cases (Environmental Courts, Court of Appeals and Supreme Court), as well as other documents and previous research in the territory (reports from administrative agencies, anthropological reports, historical literature on the colonization of the territory, among others). I also conducted a semi-structured interview with two Statkraft managers in Chile in April 2023. This allowed me to collect relevant information on the legal cases linked to the conflict, and to understand in depth how state agencies and the company have understood the impacts of these projects in relation to the river, the communities and the ngen.

Since a central aim of this research is the process of cultural translation between normative orders that takes place in this case, a crucial piece of my strategy was ethnographic participant observation. In this context, I participated in several ceremonies to which I was invited as a wenui (friend), which allowed me to become familiar with and learn first-hand about the dense cosmogony that exists in this territory around the Ngen Mapu Kintuantü and the Pilmaiquén River.

A central element of my ethnographic observation also took place through the trawün that we held periodically to inform and make decisions about legal cases. The trawün correspond to work meetings and collective decision making. An important facet of the trawün is the exchange of dreams (pewma), through which profound local knowledge is expressed, and community members and ancestral authorities connect with the territory and their ancestors. The dialogue that is generated around this type of practices is fundamental to make diagnoses of the situations experienced in the territory, deliberate, and make decisions under the mantle of wisdom. In this context, the traditional form of conversation is called nütram. This way of working, which we have been practicing since I started working with the Aylla Rewe Ngen Mapu Kintuantü, has allowed us to build mutual trust and develop a co-learning that evokes what Kovach calls “conversation as method”, a dialogic approach to collect and co-create knowledge based on the indigenous relational tradition (Kovach Citation2020, 44). This process provided me with a mechanism to involve the Aylla rewe leaders in the analysis of the data, with the aim of identifying significant differences in the way the state and the company understood the river and the ngen. The trawün were also instrumental in discussing with them how they would like to communicate aspects of their worldview to the public in a collaborative writing process.

This research approach is appropriate for studying indigenous rights as an outsider to the Mapuche territory, since it allows me to work with them to understand how the law works in the service of territorial needs, which has been defined as a methodological agreement that I have made with long term collaborators to elaborate and prepare legal cases with Mapuche territories and technical support professionals (Kelly, Guerra-Schleef, and Valdés-Negroni Citation2021). This is critical given my partial perspective as a non-indigenous human rights defender of Chilean descent, educated in Western academic institutions in Chile. Thus, even though the ancestral authorities and communities that make up the Aylla Rewe Ngen Mapu Kintuantü have entrusted me with the responsibility of sharing their testimonies and stories, as well as translating and representing their claims before Chilean administrative and judicial authorities, I do not claim to have universal knowledge about their territorial traditions, epistemic frameworks and cosmovisions.

Finally, it is important to note that this work, although by a single author, draws on knowledge generated from previous writing collaborations. Particularly important to me have been the collaborations with Sarah Kelly, an American geographer I met in 2016 while working on an indigenous consultation process in the Ranco lake. At the time Sarah, along with José Miguel Valdés-Negroni and her partner Julio Muñoz, were investigating and learning about the development of small hydroelectric power plants in the territory of the Alianza Territorial del Puelwillimapu (Kelly Citation2018a; Kelly, Guerra-Schleef, and Valdés-Negroni Citation2021; Kelly Citation2021; Kelly and Negroni Citation2020; Valdés-Negroni Citation2017). Our affinities in terms of political, conceptual, and methodological concerns have led us to forge a collaborative work that has resulted, among other things, in the preparation of various reports and documents to support legal strategies and critically reflect on the territorial defense of the Williche organizations with which we work (Kelly, Valdes-Negroni, and Guerra-Schleef Citation2017; Kelly Citation2018b; Kelly Citation2019a; Kelly, Guerra-Schleef, and Valdés-Negroni Citation2021). In this way, both the problem and the research questions presented here reflect, in an important way, the long and interesting debates in which I have participated in. This speaks for within the organization where I worked, and as well for with the communities and other professionals with whom I work.

Theoretical framework

A socio-legal approach: two lenses of hermeneutic injustice and legal pluralism

This paper combines two analytical lenses to examine the forms of injustice at the heart of the Pilmaiken case: legal pluralism and epistemic injustice. Both lenses offer an appropriate socio-legal approach to examine the forms of structural injustice experienced by indigenous peoples as they seek to make their epistemic and normative frameworks legible through the legal categories of state law.

The evolving field of legal pluralism has proven enormously fruitful in challenging ideas about the centrality of state law and raising awareness about the diversity of ways in which individuals and groups interact with the law. The concept of legal pluralism, as currently used in legal anthropology, describes the multiple forms that law takes within communities, regions, particular states or at the global level, a “[…] system produced to an important extent by processes of colonialism and postcolonialism” (Merry Citation2012, 62). Plural legal situations have different but coexisting conceptions of justice, permissible actions, valid transactions, as well as ideas and procedures for handling conflicts in the same social space (Merry Citation1988; von Benda-Beckmann Citation2001; von Benda-Beckmann Citation2002, 38).

Here, it is important to note that the initial studies on legal pluralism have evolved from an initial view that imagined the coexistence of different legal orders in the same socio-political space as separate entities in a hierarchical relationship -as occurred in the dual legal systems common to British colonialism- to a theory of unequal but mutually constitutive legal orders (Moore Citation1973; Griffiths Citation1986; Santos Citation1987; Merry Citation1988; Prieto Citation2012). In this context, the important issue to understand in contemporary studies of legal pluralism is the interaction between legal systems, leading to new questions that emphasize bidirectionality, co-constitution, hybridization and the dialectic of influence (Merry Citation2012, 68; Santos Citation1987).

In this context, this paper seeks to contribute to new studies on legal pluralism by examining the interaction between state law and indigenous peoples’ legal systems, focusing on the problems of translation that these groups experience when they attempt to make their normative worlds legible using the legal categories of colonizing states. The aim is to be able to deepen our view of legal complexity through a careful analysis of the unequal power relations that arise when indigenous peoples use concepts and categories of epistemic communities that are in a better position to influence state regulatory and decision-making processes (von Benda-Beckmann and Turner Citation2018, 265).

Considering the conversation above, a key contribution of this paper to legal pluralism studies is its proposal to examine problems of translation between normative orders through the concept of "epistemic injustice." This will allow me to explore how translation and the politics of translation are shaping inequalities by manipulating the legal records of marginalized groups to undermine the validity of their claims and rights in environmental assessment procedures. Initially formulated by Fricker (Citation2007), the concept of "epistemic injustice" refers to those forms of distinctly epistemic injustice (as opposed to economic or other forms of injustice), which occur when certain subjects or groups are harmed in their ability to know due to prejudicial stereotypes held against them.

Under Fricker’s initial scheme, epistemic injustice can occur in the form of “testimonial” or “hermeneutic” injustice, the latter category being the most relevant for the purposes of this paper. Indeed, while testimonial injustice arises when someone is wronged in his or her capacity as a giver of knowledge, by unduly excluding him or her from the communal epistemic practices of sharing and pooling knowledge (Fricker Citation2021, 97); hermeneutic injustice occurs when certain disempowered individuals or groups are unable to make intelligible some aspect of their own social experience due to a “gap” in the available hermeneutic resources, as a consequence of a denial of full and equal participation in the social practices by which meanings are generated, leading to a structural identity bias or prejudice in the available collective hermeneutic resources (Fricker Citation2007, 237–258).

In this way, the origin of hermeneutic injustice is structural -a hermeneutic background discrimination- it is situated in the unequal backgrounds of hermeneutic opportunities. What I am referring to is that some speakers are situated in an unfair and disadvantaged context, both to understand and to get others to understand this same experience of disadvantage (which is yet another form of indirect discrimination) (Fricker Citation2021).

As several scholars have pointed out, the idea that one’s experience can be obscured from collective understanding could receive both a cognitivist and a communicative reading (Goetze Citation2018). In the cognitivist reading, which is given priority in Fricker’s early work, the “gap” that exists in hermeneutic resources renders one incapable of making sense of or understanding one’s experience (Lupin and Leo 2020, 7). Thus, victims of hermeneutic injustice find themselves having some social experiences through a “dark mirror”, with at best ill-fitting meanings to fall back on in the effort to make them intelligible (Fricker Citation2007, 240–241). In communicative reading, on the other hand, being unable to make one’s own experience intelligible is an issue that occurs when one is prevented from sharing with others some aspect of one’s experience that one understands perfectly well. While a hermeneutic “gap” also occurs in this case, it is not due to a gap in shared resources, but rather to a mismatch between the hermeneutic resources or the lack of a shared framework available to the speaker and the listener (Mason Citation2011; Medina Citation2012). Of course, this kind of communicative disadvantage is not usually an innocent gap -even if it remains unintentional in many cases (Fricker Citation2021, 99)- but rather a kind of blockage, of “hermeneutic domination” or “cultural imperialism”, through which the hermeneutic resources of the dominant group are actively imposed on those of the subaltern group (Young Citation1988; Catala Citation2015; Lupin and Townsend Citation2020; Dotson Citation2012)Footnote1.

As we will see from the case study presented in this paper, the cognitivist form of hermeneutic injustice is not what is involved in the difficulties indigenous peoples face in articulating their normative worlds through validated scientific languages in state decision-making processes. These peoples have highly developed knowledge systems through which they imagine their worlds and can understand and describe their experience and connection to their territories (Tsosie Citation2012; Tsosie Citation2017). In no way are they submerged in a kind of hermeneutic penumbra, nor is there a conceptual gap that hinders their self-understanding. Thus, the communicative form of hermeneutic injustice best captures the intuitive injustice that indigenous peoples face when they attempt to communicate a relevant parcel of their experience and legal sensibility to the state and dominant society.

Fricker’s proposal to address epistemic injustice is through the cultivation of corrective virtues of an individual character: the virtues of “testimonial justice” and “hermeneutic justice”. The virtue of testimonial justice, according to Fricker, corresponds to a critical awareness that neutralizes the impact of bias on the virtuous hearer’s credibility judgments, and can be exercised by the virtuous hearer performing such actions as adjusting his credibility judgment upward or reserving his judgment when they suspect that bias may be influencing their evaluation of a witness’s words (Fricker Citation2007, 147–179). Regarding hermeneutic injustice, Fricker suggests that listeners can address it by giving speakers the epistemic benefit of doubt when they struggle to make something intelligible. In other words, the virtue of hermeneutic justice requires listeners to show a state of alertness or sensitivity to the possibility that the difficulty the speaker has when trying to make something communicatively intelligible is not because it is an absurdity, but rather because of some sort of gap in collective hermeneutic resources (Fricker Citation2021). However, this individual virtue is not enough to address the hermetic injustices we have identified as communicative. Indeed, in such cases, a change at the level of a single shared epistemic frame - a "conceptual revolution" - is not enough; rather, it is necessary for agents within an epistemic framework to look outside its boundaries, seeking alternative epistemic resources outside their current framework (Dotson Citation2012, 29–35).

Consequently, by approaching my case study as a site of legal pluralism, I intend to put on an equal level the ways of knowing and the normative universes of the Mapuche-Williche communities of this territory and the legal system of the Chilean State (with logically ordered and hierarchical laws). While, by using the analytical lens of epistemic injustice, I seek to evidence the intuitive forms of injustice experienced by indigenous peoples when they attempt to communicate and make legible a relevant parcel of their experience and legal sensibility to the state and the dominant society. I will now present the two concepts through which this paper seeks to contribute to the study of the forms of epistemic injustice expressed in the coexistence and translation between normative orders in relation to my case study: legal culture and equivocation.

Legal culture

In assessing the contribution of legal pluralism to questions about the coexistence and translation of diverse legal orders, it is important to carefully define the units of analysis that constitute a legally plural field. One way of approaching legal cultures was developed by Clifford Geertz in the early 1980s.

In Local Knowledge, Geertz argues that law “[…] is not a bounded set of norms, rules, principles, values, or whatever from which jural responses to distilled events can be drawn, but part of a distinctive manner of imagining the real” (Geertz Citation1983, 173). His assertion leads him to problematize the binary distinction between law and fact. Thus, instead of focusing our attention on rules or events, Geertz proposes to look at meaning, that is, the way in which individuals and groups “[…] make sense of what they do -practically, morally, expressively… juridically- by setting it within larger frames of signification, and how they keep those larger frames in place, or try to, by organizing what they do in terms of them” (Geertz Citation1983, 180).

This hermeneutic turn in anthropology shifts toward a growing concern with the structures of meaning through which individuals and groups live their lives. This provides a way to contrast the different cultural spaces that constitute a juridically plural social field, offering a powerful analytical tool for examining the epistemic oppression experienced by indigenous peoples through state law. By comparing Islamic, Indic, and customary adat law in Indonesia, Geertz seeks to evoke a culture by choosing key terms and using them as avenues for exploring the symbol systems through which groups and individuals form, communicate, impose, share, alter or reproduce their normative worlds (Geertz Citation1983, 184 ss.). In this way, his analysis is based not on behavior but on cultural categories embedded in key terms. For example, to analyze how a given jurisdiction deals with day-to-day social problems and conflicts, this approach focuses on how it interprets them in terms of a particular “legal sensibility” which is where the revealing contrasts lie (Geertz Citation1983, 174–175). Law, Geertz argues, is “local knowledge”, “[…] vernacular characterizations of what happens connected to vernacular imaginings of what can” (Geertz Citation1983, 215).

I will return to this in the following section. However, I think it is important to anticipate that the key terms I will be comparing are the legal categories of “site of cultural significance” and “ngen.”

Cultural translation and its limits: the equivocation

Approaching legal pluralism by understanding its constituent units as legal cultures -that is, as local knowledge that constructs social life rather than simply reflecting it- allows us to frame the hermeneutical problems of comparative analysis of law in terms of anthropology’s main analytical tool: cultural translation. As Eduardo Viveiros de Castro argues “[…] in anthropology, comparison is in the service of translation and not the opposite” (Castro Citation2004, 5). However, as Castro warns, “[…] direct comparability does not necessarily signify immediate translatability, just as ontological continuity does not imply epistemological transparency” (Castro Citation2004, 4).

In this context, Castro proposes the notion of “equivocation” to reconceptualize the enterprise of translation in anthropology from a tradition anchored in an indigenous perspectivist cosmology. Perspectivism in this tradition does not refer to relativism in the same terms as multiculturalism, a subjective or cultural relativism; but to an objective or natural relativism, a “multinaturalism” (Castro Citation2004, 54). Amerindian ontologies are inherently comparative in that they presuppose a comparison between the ways in which different kinds of bodies naturally experience the world as an affective multiplicity.

Thus, equivocation does not refer to a simple error or lack of understanding, but to the “[…] failure to understand that understandings are necessarily not the same, and that they are not related to imaginary ways of ‘seeing the world’ but to the real worlds that are being seen” (Castro Citation2004, 11). In that way, relations of equivocation go beyond divergent “perspectives” of the same world or comparison between different spatial or temporal instantiations of a given sociocultural form. Rather, they occur when visions of different worlds use homonymous terms to refer to things that are not the same (Cadena Citation2010, 350).

The equivocations cannot be “corrected” or avoided, but they can be controlled. To this end, attention must be paid to the translation process - the terms and the respective differences - so that the “referential alterity” between the different positions is recognized and inserted into the conversation so that, instead of different visions of the same world (which would amount to cultural relativism), a vision of different worlds becomes evident (Castro Citation2004, 5). In other words, to translate is to assume that there is always an equivocation; it is to communicate through differences and to take seriously what the Other is saying in their effort to make himself understood, instead of silencing him by presuming a univocity -the essential similarity- between what the Other and We say (Castro Citation2004, 10).

Thus, the aim of translation in this tradition is to highlight the differences that arise in a communicative disjunctive with other beings (human and non-human), opening, exploring, emphasizing and enhancing equivocality (Castro Citation2004, 11). In short, it is a matter of “[…] alien concepts to deform and subvert the translator’s conceptual toolbox so that the intentio of the original language can be expressed within the new one” (Castro Citation2004, 5).

The notion of equivocation proposed by Castro implies a fruitful ontological turn to examine the complexity of juridical plurality when it is entangled with indigenous juridical mobilization. From a socio-legal perspective, the recognition of equivocality can shed light on the limits of the formal recognition of indigenous rights, offering a good entry point for the analysis and assessment of the often-overlapping ways in which indigenous peoples have been epistemically oppressed. In this way, by incorporating it into my analytical toolkit, I hope to present the ways through which the Williche imagine water and rivers, outside the realms of myth, folklore, and religious or multicultural tolerance (Cardoso and Pacheco-Pizarro Citation2021, 5). From this perspective, situating conflicts over water in Mapuche territory as ontological is not only a theoretical distinction, but has implications in the legal and political realms, influencing practical questions about how these conflicts are made legible in various institutional contexts and decisions are made (Cadena Citation2010).

In the following section I present my case study. I begin with some historical background of the colonization process of the Mapuche-Wlliche territory between the Pilmaiquén and Chirre rivers. Then, I contextualize the concept of ngen to the particularities of the AzMapu (Mapuche law) of this territory, with the objective of approaching the meaning of water from the perspective of the Mapuche-Williche juridical sensibility. Finally, I explain how the dense cosmogony of the Mapuche-Williche communities is translated around water and its ngen during the environmental impact assessment process of the Osorno Hydroelectric Power Plant and what the impacts of this process have been over time.

Case study: the Pilmaiken case

Historical context of the Mapuche-Williche territory between the Pilmaiquén and Chirre Rivers

In contrast to the Mapuche territory located north of the Toltén River -which enjoyed political and territorial autonomy until 1883-, by the end of the Spanish colonial period a significant part of the Futawillimapu (or “great southern territory”) had been dispossessed from ancestral residents as Hispanic hacienda ownership had begun to take hold (Comisión de Verdad Histórica y Nuevo Trato con los Pueblos Indígenas Citation2008, 445–448; Correa Citation2021, 227–233).

After the independence of Chile in 1818, land buying intensified in the Futawillimapu, a phenomenon that lasted until the mid-1820s (Comisión de Verdad Histórica y Nuevo Trato con los Pueblos Indígenas Citation2008, 448). This process was facilitated by the deregulation of indigenous property sales. To safeguard the rights that the Chilean state claimed over the Williche territory, the government of Ramón Freire dictated the Act of June 10, 1923 (also known as the “Freire Act”), granting powers to the Intendant of Valdivia to designate a prominent neighbor to demarcate the Williche lands and deliver them “in perpetual and secure ownership”. It also mandates that “[…] the surplus lands belonging to the State be measured and appraised”, to be put up for “public auction” (Correa Citation2021, 234)Footnote2. This process gave rise to the so-called “Títulos de Comisario” (Comisión de Trabajo Autónomo Mapuche Citation2008, 910–914). Under the protection of this legislation, between 1824 and 1832, some thirty “títulos de comisario’” were awarded to the pu lonko (the heads of Williche families), distributed along the coast of Osorno, in some sectors of the Bueno River (up the Pilmaiquén River) and La Unión, as well as on Ranco and Maihue lakes, recognizing an important part of the old Williche domains (Correa Citation2021, 234).

However, from 1846 onwards, a fundamental event in the history of the territorial dispossession of the Futawillimapu took place: successive waves of German settlers began to disembark in Valdivia, as part of a settlement policy promoted by the Chilean State (Correa Citation2021, 237). In a context of deregulation of Mapuche-Williche lands (a situation that lasted until 1893 when the purchase of indigenous lands was prohibited), the settlers, with the complicity of the local authorities, would deploy a battery of usurpation methods that gave rise to the current private property in the Futawillimapu (Comisión de Trabajo Autónomo Mapuche Citation2008, 914–919; Comisión de Verdad Histórica y Nuevo Trato con los Pueblos Indígenas Citation2008, 450–455).

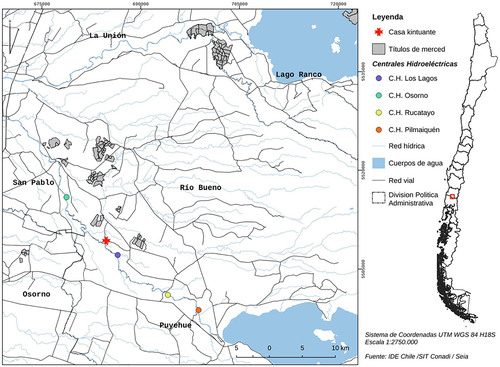

What happened in the Williche territorial space between the rivers Chirre (to the north) and Pilmaiquén (to the south), in the current Los Ríos Region, is illustrative of this process of fraudulent constitution of property for the settlers’ benefit. Thus, when the Comisión Radicadora arrived in this territory between 1913 and 1917, settler property was already established and occupied almost all the available land. This meant that the old Williche families of Maihue, Carimallin and El Roble were displaced and reduced to the few spaces still available, with only 214 hectares, for 95 people distributed in five reservation (known as “Títulos de Merced” in favor of the families (mochulla) Mafil, Queulo, Malpu and Anchil; and 65 hectares in the Lumaco sector in the name of Mr. Pedro Marriao (Correa Citation2021, 265) ().

In this process, the Mapuche-Williche families of this territory were not only reduced to quadrants that differed from their ancestral domains but were also displaced and pushed to the south of the Chirre River, away from the Pilmaiquén River. This implied the loss from their ancestral domains of both the territorial spaces that allowed their economic and material reproduction, as well as those of spiritual importance, including the ceremonial complex inhabited by the Ngen Mapu Kintuantü and Kilen Wentru, central tutelary spirits in the cosmovision of the Mapuche-Williche people, whose dwelling (renü) is located within the area that would be flooded by the construction of the Osorno Hydroelectric Power Plant (Correa Citation2021, 267).

The following is a description of the dense normativity that exists around the natural ceremonial complex of which the Pilmaiquén River and the ngen of this territory are part of, with the purpose of contrasting how this normativity is introduced in the environmental impact assessment process of the Osorno Hydroelectric Power Plant.

The natural-ceremonial complex Ngen Mapu Kintuantü and its AzMapu

To approach the meaning of water from the legal sensibility of the Mapuche-Williche communities of the Pilmaiquén River and to understand the misunderstandings in this case, it is essential to note a few things about the concept of ngen from the Mapuche law or AzMapuFootnote3. AzMapu -a term that includes both the constellations of norms and principles, as well as the investiture of the Mapuche people’s own authorities and institutions that apply and interpret them- refers to the organization of life and its complex link with the che (the Mapuche person), as well as its interaction with a given space and its internal distribution (Melin-Pehuen et al. Citation2016, 14). In this sense, AzMapu echoes the relationship between the material, spiritual and cultural dimensions of Mapuche life, where the “social” and “natural” worlds are interconnected in such a way that the transgression of the latter profoundly affects not only the social, but also this cosmopolitical node.

Regarding water, in AzMapu there is a complex constellation of local rules, obligations and rights that reproduce a symbolic order about what water is and how people should relate to it, as well as to the various non-human (and more-than-human) beings that co-inhabit a territory (Melin-Pehuen et al. Citation2016, 109). In the Mapuche conception, water is part of the territory and, as such, cannot be the property of an individual and much less can it deprive the rest of the people and animals of the use and access to it, since doing so implies a transgression that must be remedied or rectified (Melin-Pehuen et al. Citation2016, 109).

For the Mapuche “damaging the rivers is equivalent to damaging the veins of the Ñuke Mapu [Mother Earth]” (Elsa Panguilef, Lof Mapu Rupumeika, Oral communication, December 2018) Likewise, as has been widely documented, for the Mapuche, running water (Witrunko, in Mapuzungun) is known as a source of well-being for human and ecological bodies; on the contrary, stagnant water brings disease or illness (Comisión de Trabajo Autónomo Mapuche Citation2008, 1226; Cardoso and Pacheco-Pizarro Citation2021; Kelly Citation2021). This is the reason why the dammed waters generated by hydroelectric power plants in rivers have a meaning connected to transgression and a sense of attack.

For the Mapuche, water -like the other elements of the territory- has its ngen (Caniullan and Mellico Citation2017, 44). Although one of the usual translations of the term ngen is “owner of the place”, rather than a subject “who has dominion or lordship over someone or something” (Real Academia Española, n.d., definition 1), “[…] the so-called ngen is a spiritual force proper to the place that is in relation to plants, minerals, humans, fungi, animals and water" (Llancaman Citation2020, 5).

From this perspective, the ngen “[…] are the guardians, governors or regulators of a given territory…” (Machi Millaray Huichalaf, Oral communication, January 30th, 2021); who exist independently of humans, but who must be asked for permission, as well as express gratitude and respect for their sanctioning power (Sánchez Citation2001). These guardians configure the ordering (Az) of water (Ko), that is, its own characteristic which, in its constant relationship with che, establishes material and immaterial links that delimit and order the inhabited spaces, and which are manifested mainly in the spiritual, health and ceremonial spheres, among others. From this perspective, the concept of ngen is central to understanding the Az of water, and abusing this element implies violating the care and transgressing the duties towards its rulers, which brings with it sanctions towards the transgressors and the communities.

This can be clearly seen in the case of the natural ceremonial complex around the Pilmaiquén river and the ngen Kintuantü and Kilen Wentru. The dwelling (renü) of the ngen Kintuantü and Kilen Wentru is located on the south bank of the Pilmaiquén River, in the sector of Maihue-Carimallin, in Río Bueno, in the current Los Ríos Region. The dwelling of Kintuantü and Kilen Wentru is part of a sacred complex of Mapuche-Williche ceremonial use, which constitutes a unit with the old cemetery (eltuwe) that exists in Maihue, the prayer field (gillatuwe) and the Pilmaiquén River, one of the main tributaries of the Wenuleufu (the “river from the sky”), name with which the river Bueno is called in Mapuzungun (Moulian and Espinoza Citation2015). In the words of Machi Millaray Huichalaf, all these elements:

[…] are physically and symbolically related by the amunkowe (movement of the waters) that marks the path followed by the spirits in the direction of the wenu mapu (the land of the sky). In […] the dwellings of Kintuantü and Kilen Wentru there is an upwelling of waters that flow below the cemetery. Its course, protected by an ancient native forest and wetland, leads to the Pilmaiquén River, which flows into the […] Wenu Leufu […], forming a spiritual path linking the kuifikeche (ancestors) with the ngen mapu, whose transcendent character must be cared for through the periodic practice of prayers in the ancient ngillatuwe located in the vicinity of the cemetery (Huichalaf Citation2019).

Likewise, the dwelling of the Ngen Mapu Kintuantü is linked to other spaces of spiritual importance, such as the volcanic Cordon Caulle, as well as other ngen, as is the case of his sister and brother, Mari Antu and Grandfather Wuentiao, whose dwellings are in Mantilhue, on the north shore of Puyehue lake, and Pucatrihue, in the coastal sector of San Juan de la Costa, respectively. These relationships form a spiritual chain that extends along the Fütawillimapu and connects the coastal communities with those located in the valleys and the mountain range (Millahueque Citation2011). These connections, which follow the natural order of the watershed, imply that there is a permanent pilgrimage to request permission from the Ngen Mapu Kintuantü and that the various ceremonies that take place in this extensive territory are carried out in the direction of his dwelling place (Correa, Morales, and Moulian Citation2012).

As noted, although the ancient ownership of the land where the dwelling of the Ngen Kintuantü is located belongs by ancestral right to the Mapuche-Williche lineages of the El Roble/Maihue/Carimallin territories, in the context of the colonization of this territory it was taken away from them. However, this did not prevent the communities from continuing to use this space for their ceremonial activities, since, through informal agreements, the successive legal owners tolerated the access of the local Mapuche congregations to this important ceremonial complex. This situation changed radically when the hydroelectric power plants of Empresa Eléctrica Pilmaiquén S.A. (EEP) entered the Environmental Impact Assessment System (EIAS).

The following section will examine how the dense cosmogony surrounding this spiritual assemblage is made legible in the context of the environmental assessment procedure of the Osorno Hydroelectric Power Plant on the Pilmaiquén River, through the category of “site of cultural significance”, and the impacts this has had over the years in which this conflict has developed.

The conflict of Statkraft’s hydroelectric power plants on the Pilmaiquén River

Although the current conflict over the development of the hydroelectric potential of the Pilmaiquén River involves three hydroelectric power plants owned by EEP -controlled since 2014 by the Norwegian state-owned Statkraft through its Chilean subsidiary Statkraft Chile Inversiones Eléctricas Ltda. (Statkraft Citation2022)-, it was during the environmental assessment of the Osorno Hydroelectric Power Plant where the discussion about the impacts that these projects have on the Kintuantü and Kilen Wentru emerged for the first time, as a consequence of the direct flooding of an important part of this natural Mapuche-Williche complex of ceremonial useFootnote4. While the focus of my analysis is on the Osorno Power Plant, I do not intend to ignore the impacts that the other projects have on the natural ceremonial Williche center that exists in this territory, which, as noted, is part of the Pilmaiquén River.

When EEP submitted the Environmental Impact Study (EIS) for the Osorno Generating project to the EIAS in 2007 (58.2 MW), it declared that: “[i]n the area of influence of the project there are no […] legally constituted Mapuche indigenous communities, or of any other ethnicity” (Empresa Eléctrica Pilmaiquén S.A Citation2007). This filing made this claim despite implying the intervention and flooding of an important part of the Mapuche-Williche natural ceremonial center linked to the dwelling of the Ngen Mapu Kintuantü, which at that time was well known by various state institutions. Along with demonstrating the lack of prior research by the company, these claims resulted in the absolute invisibility of the Mapuche-Williche communities in this territory, which also meant that no measures were considered to address the impacts on the natural ceremonial complex (Correa Citation2011).

This deficiency was noted during the environmental assessment of this project by the National Indigenous Development Corporation (“CONADI” for its acronym in Spanish), the state agency in charge of indigenous policy in Chile. It is in this context that the natural complex of ceremonial use that exists around the river and ngen is made visible for the first time as a “site of cultural significance”, category used by CONADI to, in the context of its legal mandate, refer to those places of special protection located “[…] within or outside of indigenous communities that are relevant to their members, because they are linked to their beliefs, histories and customs, with their past or present cultural manifestations, which lead to a feeling of social cohesion and of belonging and identification to a determined group” (Pozo and Millanao Citation2022, 17). According to CONADI:

The EIS of the Osorno hydroelectric power plant, has not implemented the necessary actions to investigate the existence of sites of cultural significance, in this sense, it should be mentioned that local communities, such as, the indigenous communities of Maihue Pilmaiquen, el Roble and Mantilhue, have indicated the existence of sacred sites near the banks of the Pilmaiquén river, which are in potential danger, with the installation of the power plant (Corporación Nacional de Desarrollo Indígena Citation2007).

This was again objected to by CONADI. Given that the environmental assessment of this project coincided with Chile’s ratification of ILO Convention 169, this agency requested “[…] by virtue […] of Act 19,253 [Indigenous Act] and […] ILO Convention 169, the participation of the Indigenous Communities associated with the Kintuante Site of Cultural Significance is required for the process of designing a site mitigation plan” (Corporación Nacional de Desarrollo Indígena Citation2008). In addition, CONADI stated that this “process of information and participation of the indigenous communities” should include “[…] both the Ancestral, Religious and Traditional Authorities and the indigenous population in general”, and inform “[…] about the implementation of the project and its environmental impacts […], since the information gathered in the field by CONADI indicates a lack of knowledge of the indigenous population surrounding the project” (Corporación Nacional de Desarrollo Indígena Citation2008). Finally, CONADI claimed that this participation process should “[…] be carried out in good faith, as mentioned in Article 6 of ILO Convention 169, through adequate and relevant means for the population in question, in order to ensure that the communities correctly understand the potential impact of the project and that they give their opinion and consent to the reparation and/or mitigation measures that the owner commits to” (Corporación Nacional de Desarrollo Indígena Citation2008).

However, as the ILO Convention 169 was to enter into force twelve months after the instrument of ratification was filed with the ILO, EEP pressured the environmental authority at the time (CONAMA) to avoid the implementation of participation and consultation mechanisms with the indigenous institutions representing the territory. To this end, the proponent submitted several notarized minutes of meetings where the legal representatives of the indigenous organizations unilaterally identified by EEP gave their approval to the mitigation plan proposed by the company (Empresa Eléctrica Pilmaiquén S.A Citation2009).

On June 30, 2009, two and a half months before the ILO Convention 169 entered into full force in Chile, CONAMA decided to approve the Osorno Hydroelectric Power Plant without implementing a prior consultation process but establishing as a condition for its execution the obligation that the owner must:

[…] submit, prior to the start of the Project, Meeting Minutes that demonstrate the consent of the 3 indigenous communities identified within the baseline for the Human Environment study with respect to the mitigation measures, and which are associated with the site of cultural significance ‘Kintuante’. This documentation must be submitted to CONADI, and must contain the consent of the ancestral authorities of the area, of the directives of these communities and of the related partners (Comisión Nacional del Medio Ambiente Citation2009, considerando 12.2).

Conflict in the territory came to a head in 2011, when the then owner of the land where the Ngen Mapu Kintuantü dwelling was located, restricted access to the communities and began to illegally cut down the native forest that protected it. To stop the destruction of the natural ceremonial complex, the Mapuche-Williche communities and ancestral authorities of the territory asked CONADI to buy the land (Comunidades de El Roble-Carimallin y Mantilhue Citation2011) and filed a protective action with the Court of Appeals of Valdivia.

As the conflict intensified, the communities entered the property to stop the settler’s actions. Although the appeal for protection filed by the communities was accepted in the first instance by the Court of Appeals of Valdivia, ordering the settler “[…] to cease his activities of illegal logging of ancient trees […] and to allow the petitioners free access to the ceremonial site […] during the summer season and for the sole purpose of performing prayers” (Millaray Huichalaf Pradines y Otros C/Juan H. Ortiz Ortiz Citation2012); finally the Supreme Court decided to reject it, considering that the occupation of the land in conflict by the communities constituted an exercise of "self-protection" unacceptable in the light of the constitutional order in force, which violated the property rights of the current owner (Millaray Huichalaf Pradines y Otros CONTRA Juan H. Ortiz Ortiz Citation2012). Once again, the conflict around the ceremonial natural complex that exists around the Pilmaiquén river and the Ngen Kintuantü was reduced to a problem of access to the “site” for the development of religious activities, and where pre-eminence in the event of a collision between the Mapuche ancestral property right and the private property of the settler is held by the latter.

In parallel, in 2012, EEP bought the land where the dwelling of the Ngen Kintuantü is located, with the objective of complying with the condition imposed in the environmental permit of the project (Empresa Eléctrica Pilmaiquén S.A Citation2013). The company began to meet with the indigenous organizations identified in its baseline study and promised restitution of the land. However, these meetings took place during a period of high criminalization in the area, with ancestral leaders and authorities being charged with crimes and some deprived of their liberty. This was the case of Machi Millaray, who, by openly rejecting the project, began to be investigated and criminally prosecuted (Castillo and Ramirez Citation2017, 68).

Given that this conflict coincided with the implementation of the new environmental institutions in ChileFootnote5, following a complaint made by organizations and ancestral authorities of the territory, in 2016, the Superintendence of the Environment (“SMA” for its acronym in Spanish) determined that the minutes presented by the company in 2014 did not fulfill its obligation to obtain the consent of the communities identified during the evaluation regarding the mitigation measure associated with the site of cultural significance, as required by the environmental permit for the Osorno Plant. The SMA also observed that it was not possible to determine whether the methodology used by EEP complied with the standards of ILO Convention 169 and whether the participation process should only include organizations with legal status identified unilaterally by the company (Superintendencia del Medio Ambiente Citation2016).

Consequently, the SMA requested the Environmental Evaluation Service (“SEA” for its acronym in Spanish) to administratively interpret this issue. Based on this administrative consultation, the SEA validated the criteria used by the EEP to determine which communities could participate in this indigenous participation procedure. Along with the above, the SEA pointed out that this participation process was not an indigenous consultation as such, since it was an obligation of the company, but that both the methodology and the meaning and scope of the term "consent" in the permit environment should comply with ILO Convention 169 and the national regulation of the indigenous right to prior consultation (Servicio de Evaluación Ambiental Citation2016).

To reverse this judgement, Machi Millaray, together with the Koyam Ke Che Community and the Wenuleufu Association, opposed this decision before the Second Environmental Court, arguing that the SEA had illegally omitted the technical opinion of CONADI, and that the obligation to implement an indigenous consultation process was a duty of the Chilean state and not of a private company. This action was accepted by the Second Environmental Court (Huichalaf Pradines Millaray y otro/Dirección ejecutiva del Servicio de Evaluación Ambiental (Res. Ex. N° 0711 and de 6 de junio de 2018) 2018) 2020) and subsequently confirmed by the Supreme Court (Huichalaf/Servicio de Evaluación Ambiental Citation2020), ordering the SEA to reopen the procedure for interpretation of the RCA, this time with CONADI’s pronouncement to clarify the controversial aspects of the environmental license.

Although Statkraft recently announced that it had renounced the environmental permit for the Osorno power plant -given its impacts on the “site of cultural significance” inhabited by the Ngen Kintuantü, prioritizing the construction of the Los Lagos power plant (M.T.G., interview, April 10, 2023)-, the negotiations initiated by EEP (and continued by Statkraft) have led to internal divisions that have had lasting effects on the forms of representation of the ancestral organizations and authorities of the territory (Kelly, Guerra-Schleef, and Valdés-Negroni Citation2021). From this process, new indigenous communities with legal status have emerged, such as Koyam Ke Che, which organizes the dissident families of El Roble, which, together with indigenous community Leufu Pilmaiquén Maihue, have organized opposition to the company’s hydroelectric projects on the Pilmaiquén River. However, this shows the fractures in the families and sociological communities of these territories, where the cleavage has been the support or rejection of the hydroelectric projects. The conflict over indigenous representation also led to the creation of the Wenuleufu Association, which brings together several pu Lonko of the territory, as well as 47 communities with legal status in the commune of Río Bueno.

In 2014 Statkraft purchased the hydroelectric projects, water rights, and land rights of the project (Maria Teresa González, interview, April 10, 2023). As other scholars have demonstrated, a market exists in Chile for purchasing water rights with approved EISs (Kelly and Negroni Citation2020). As the current landowner, Statkraft has upheld EEP’s refusal to sell to CONADI the lands where a fundamental part of the natural complex for ceremonial use around the Pilmaiquén river is located (Empresa Eléctrica Pilmaiquén S.A Citation2013), arguing that they have acquired these lands for the purpose of handing over the ceremonial area to the indigenous communities (Empresa Eléctrica Pilmaiquén S.A./Statkraft Chile Inversiones Electricas Ltda. 2021a).

Relatedly, in 2018 Statkraft circulated a proposal with the main organizations and ancestral authorities who represent the territory, requesting that they identify the legal figure that would hold title to the transfer (Statkraft Citation2018). This has been used by CONADI as an excuse to advance in the purchase procedure, the only mechanism contemplated in the Chilean legal system to solve this type of territorial conflicts, granting to the company -Statkraft- the responsibility of defining when, how and to whom the registered ownership of the central part of the ceremonial complex where the Kintuantü inhabits will be assigned (Corporación Nacional de Desarrollo Indígena Citation2021).

As a lawyer collaborating with the ancestral authorities and Mapuche-Williche communities that oppose these hydroelectric projects, I have been able to observe how, as the conflict has escalated and the communities have used the institutional mechanisms available to exercise their rights, this company has strategically used its commitment to restore the land where Ngen Mapu Kintuantü’s house is located. Effectively, they have favored those people with whom it has negotiated since the environmental evaluation of the Osorno Power Plant and forced confrontation with the communities of the territory around the ownership of this important complex Mapuche-Williche ceremonial.

It is important to note that Statkraft has not only inherited the negotiations and agreements, but has maintained and used them strategically in the context of the construction of the Los Lagos power plant, taking an active role in direct negotiation with the communities, appealing both to the condition imposed in the environmental permit for the Osorno power plant and to its corporate commitments to the human rights of indigenous peoples (Statkraft Citation2022, 66). However, the ancestral authorities and Mapuche-Williche organizations that oppose these projects (Empresa Eléctrica Pilmaiquén S.A./Statkraft Chile Inversiones Eléctricas Ltda Citation2021a) have refused to participate in the company’s dialogue, arguing that it would be a strategy that only seeks to confront local communities around the ownership of part of the ceremonial natural complex, in circumstances where the responsibility for the return of this sacred space is an obligation of the Chilean State (Aylwin, Didier, and Guerra Citation2019, 65–66).

An important milestone in this process occurred in May 2021, when the ancestral authorities and Mapuche-Williche communities that oppose the hydroelectric plants on the Pilmaiquén River became aware of Statkraft’s unilateral decision to transfer the land where the Ngen Mapu Kintuantü is located to an indigenous association with legal personality called Señor Kintuantü, recently created with the support of the company. In the words of a Statkraft representative in Chile, this organization would group together the lepunero who would be “the true ancestral authorities of the territory” (K.O., interview, April 10, 2023). This occurred in the context of a consultancy research commissioned by Statkraft and carried out by a Chilean academic institution to identify the organization that would be the owner of the transfer (Empresa Eléctrica Pilmaiquén S.A./Statkraft Chile Inversiones Eléctricas Ltda Citation2021a).

However, I have also observed that while Statkraft has negotiated and articulated support in the communities closest to the proposed power plants and maintained the strategy launched in the context of the environmental assessment of the Osorno Power Plant; the ancestral organizations and authorities that oppose these initiatives have revitalized political alliances with the communities of the extensive territory for which the Ngen Mapu Kintuantü is a spiritual reference, as is the case of those located around the Caulle Volcanic Range and in the coast.

In short, even though Statkraft’s strategy of transferring ownership of the land where Ngen Kintuantü’s residence is located is currently paralyzed by a Supreme Court rulingFootnote6, I have been able to verify how community relations nearest to hydroelectric development have deteriorated and conflicts between families and community members have become more acute. Likewise, profound changes are evident in the forms of Mapuche-Williche representation of the territory. The use of institutional and legal mechanisms by ancestral organizations and authorities that oppose Statkraft’s initiatives in the Pilmaiquén RiverFootnote7 has led the company to support the creation of new indigenous organizations with legal personality in the territory that are functional to the interests of the company. In this way, negotiations have modified community interactions for more than 15 years, causing fractures and divisions in families that will last for a long time (Kelly, Guerra-Schleef, and Valdés-Negroni Citation2021). The continuous interventions have generated friction in the territory and have consolidated the divisions between the various organizations that have arisen as the conflict has developed in the basin. This, of course, does not mean that there is perfect unity among those who oppose Statkraft’s projects. There is a history of alliances and divisions, at the center of which are the interventions and negotiations of the company that owns the Los Lagos and Osorno power plants.

Discussion: the Pilmaiken case as a site of legal pluralism

In this section I discuss the limits of the translation process that has taken place in my case study, exploring two equivocations that are made explicit in this case.

First equivocal site: from ngen to “site of cultural significance”

To understand the problems of hermeneutic injustice, as well as the complexities and interrelationships that exist at the heart of the Pilmaiken case as a site of legal pluralism, we must first explore the ontological aspects that define each of the legal spheres that are interacting in this territory. This allows us to examine the equivocations that emerge from this conflict that affect the way in which the impacts of these projects on the river, communities and ngen are understood. When we turn to the AzMapu of the ceremonial complex inhabited by the Ngen Kintuantü and Kilen Wentru, it is possible to observe how water is considered not only as H2O or a natural resource available for exploitation, but as a profoundly important actor in the realization of all aspects of life, as well as an assembling force between human and non-human collectives, connecting the living with their ancestors. In this way, the fragmentation of the Pilmaiquén river for the Mapuche communities is not only the loss of a productive resource, but also has a series of impacts on the normative world of the communities, the Ngen Mapu and the forces (newen) that maintain the cosmic balances between human beings (past, present and future) and non-human beings that inhabit the territory.

As noted, for Geertz (Citation1983) worldviews are always normative and, consequently, empirical experiences are inevitably interwoven with the symbolic worlds we inhabit. In relation to the case study, the local norms, rights, and obligations that regulate how water should be managed, reflect, and reproduce a symbolic order regarding what water is and how people should relate to it. This symbolic order is based on concrete ethics and shared values that are rooted in the material relationships among people, watercourses and ngen mapu, where obligations are not separate to water-related traditions and customs. Thus, the spiritual geography of the ngen is at the same time a geographical representation of the normative world of the communities, which is central to understanding how they contextualize the impacts of hydropower plants both in relation to themselves and to the river.

The rules, rights, and obligations of communities, as well as their vernacular ways of imagining water, are not pre-political, nor are they frozen in time and space, nor are they purely cultural. They are always becoming something different in relation to the political-economic processes, power relations and conflicts where they are located. That is why the Williche communities are constantly transforming and mobilizing their normative worlds, as a way of confronting the state law that aims to standardize how water should be managed and, more specifically, to evaluate the environmental impacts that certain development projects may have on rivers.

Considering the EIAS as a privileged site where the conflict we are studying has been channeled, this mobilization has occurred within a certain political economy of water reproduced by state rules, rights and obligations that present water under the state and neoliberal symbolic order: as a resource that can be freely appropriated and traded, and that can be managed regardless of who the holders of the land rights are.

It is at this point where a first equivocation or hermeneutic problem of translation arises between the different legal spheres and sensibilities that are interacting in this case. As noted, defining the term ngen from the perspective of the communities, as well as the dense cosmogony surrounding the natural complex for ceremonial use that exist around Pilmaiquén river, is an extremely complex task. This is the reason why, to make this reality understandable for the environmental institutions in the environmental assessment, the concept of “site of cultural significance” is used. However, as Llancaman points out:

From ngen to ‘site’ there is a considerable distance. A site […] can be measured and identified in coordinates, it is thus delimited and enclosed. The ngen on the other hand cannot be understood as contained in limits, it represents in every sense an excess […]. Ngen is in-common […], and from my perspective, the first word about ngen is that even when it includes human beings, it does not depend on them, and in turn the human cannot be conceived as separate from the first (Llancaman Citation2020, 5).

This reduction of significance is understandable within the dynamics of the conflict: the category “site of cultural significance” is a criterion that can be admitted as an argument for environmental institutions since it is comparable and measurable. In view of the need to exchange information and communicate experiences about living in space, the communities can accept the reduction of the new term, even if it is insufficient. In other words, mediation through religious practice is the way state regulation incorporates the contents of the normative Williche worlds, but via foreign categories (Tsosie Citation2012; Tsosie Citation2017).

However, this way of understanding the impacts of this project is based on a fragmentary understanding of the territory (Kelly, Guerra-Schleef, and Valdés-Negroni Citation2021), which is produced by a mismatch between discursive practices that make central aspects of the experience of the affected communities unintelligible to the environmental assessment. As we have seen, the sacred spaces that the communities have fought to protect are not only “land” or “water”, but they are also more than that; they are the river, known people, guardian beings, forces and living beings (Cadena Citation2015). Therefore, the water of this territory cannot be treated as a mere object over which a person can claim ownership, to be managed independently of the other beings (human and non-human) that inhabit the territory.

Thinking of rivers and water in Mapuche-Williche territories (whether or not labeled as "sacred") as places of equivocation –which allow circuits between partially connected worlds, without necessarily creating a unified system- can help to become aware of how the Chilean legal system transforms indigenous socio-natural worlds in its attempt to make them legible within its conceptual coordinates. As Marisol de la Cadena (Citation2010) argues, when we do not become aware that rivers (or any other entity whose meaning we do not doubt) are equivocal, the dispute is interpreted as a "problem between two cultures" rather than an ontological controversy (351–352).

In this way, the destiny of the river and the ngen mapu is defined by the only culture that, claiming universal principles, provides "technical" solutions that, however, are incapable of avoiding possible local deaths. Thus, if we want to obtain different results, we must take the problem to a different plane; to the political moment in which the ontological division between humans and nature arises and creates politics as a human affair and relegates nature to scientific representation. Seen from this perspective -which reveals the epistemic politics of modern politics- the conflict would change and, instead of a cultural problem between universal progress and local "beliefs", the fate of the river and the ngen mapu emerges as a conflict between worlds, requiring symmetrical disagreement.

In other words, by mobilizing the river and its ngen as sensitive entities, the Mapuche-Williche communities and ancestral authorities of this territory do not invoke a “belief” (which reproduces the Western dualism “science/belief” or “nature/culture”); but, as Escobar argues, “[…] from a whole episteme and ontology that do not function on the basis of these binaries” (Escobar Citation2014, 117). In this “relational ontologies”, as Escobar calls them, humans, and non-humans (the organic, the non-organic, and the supernatural or spiritual) form an integral part of the world of the communities of this territory in their multiple interrelationships as sentient beings (Escobar Citation2014).

Second equivocal site: spatial logics of impact

Relatedly, a second equivocation emerges in this case related to the various spatial logics that interact in this case, which, in my opinion, demonstrates that the Chilean state is not the only actor that is giving meaning to indigenous rights. As discussed, in this case it was the incumbent company that ultimately determined the spatial scope of its project’s affectation, enacting a key state administrative practice, such as defining who will be considered as affected and, therefore, as interested persons: holders of rights and interests that will be compromised with the implementation of the project. As shown in the Pilmaiken case, the company strategically took advantage of this situation, identifying as directly affected only the closest indigenous communities with the legal status and with which it has negotiated. This strategy, as we have seen, was validated by the Chilean state in the framework of the environmental assessment of the Osorno Power Plant and, even though this project is currently abandoned, it has been projected in time beyond this administrative procedure. This is evident in the way in which this company has used its previous negotiations with the communities that it itself identified as affected during the environmental evaluation process of the Osorno Power Plant and the property it maintains on the land where Ngen Kintuantü’s residence is located, in the context of the development and construction of the Los Lagos Power Plant.

However, this spatial logic defined by the company in charge of these projects is opposed to the broader spiritual and legal geography of the natural complex of ceremonial use that exists around the Pilmaiquén River. Indeed, in contrast to the State’s and the company’s drive to spatially limit the impacts - and, consequently, who is affected - the communities that oppose these hydroelectric projects claim that the river, the ngen and all the communities whose territories make up the spiritual chain around this natural ceremonial center are affected. This is because, although the communities closest to the Ngen Kintuantü play the role of custodians of the space, they are not the “owners” of the site, insofar as ownership of the ngen is inconceivable from their AzMapu. From this perspective, it is not enough for the owner company to negotiate the consent of some families and nearby communities to validate the intervention of this ceremonial complex, since what is at stake in this case is a territory in its broad material, epistemic, cultural, and ontological conception.

Conclusions

In this paper I have used various analytical tools from anthropology to construct a framework that allows us to examine the problems of structural hermeneutic injustice that emerge in the Pilmaiken case as a site of legal pluralism. I have focused my analysis on two equivocations arising from the process through which the environmental institutionality translated the dense normativity of the Mapuche-Williche communities around the Pilmaiquén River and the Ngen Mapu Kintuantü during the environmental assessment of the Osorno Hydroelectric Power Plant, with the aim of making the impacts of this project legible in this institutional context.

As I argued, in this case, the institutional translation of ngen to “site of cultural significance”, as well as the company’s subsequent proposal to fill in the terrace that is part of the dwelling of the Ngen Mapu Kintuantü, reproduced a structural form of epistemic injustice of a hermeneutic type, reflecting the political and business impulse behind dominant multiculturalism, which continues to reduce the normative and juridical worlds of indigenous peoples to mere folklore, to a mere belief that belongs to another “culture”. This, moreover, has had long-lasting effects on the way in which the company and the environmental institutions have understood the spatial dimension of the impacts of these projects in relation to the communities linked to the natural ceremonial complex that exists around the Pilmaiquén River.

Now, with this I do not mean to argue that the category of “site of cultural significance” cannot be re-signified and epistemically decolonized in a new scenario. However, to move in this direction it is essential to be aware of the Western religious discourse and practice that operates through this category, which reproduces models of thought based on a dualistic rationality: the nature/culture binary. The change of shared understandings is not an automatic process of hermeneutical redefinition but requires political actions aimed at disrupting the power relations that underlie these understandings, making visible exclusion, institutional violence and what Pohlhaus has called “willful hermeneutical ignorance” (Pohlhaus Citation2012).